Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 2S

H2H Marketing: Putting Trust add Brand in Strategic Management Focus

Philip Kotler, Northwestern University

Waldemar Pfoertsch, Pforzheim University of Applied Sciences

Uwe Sponholz, University of Applied Sciences Wurzburg-Schweinfurt

Keywords :

Brand Management, Reputation Management, H2H Marketing, Rebranding

Abstract

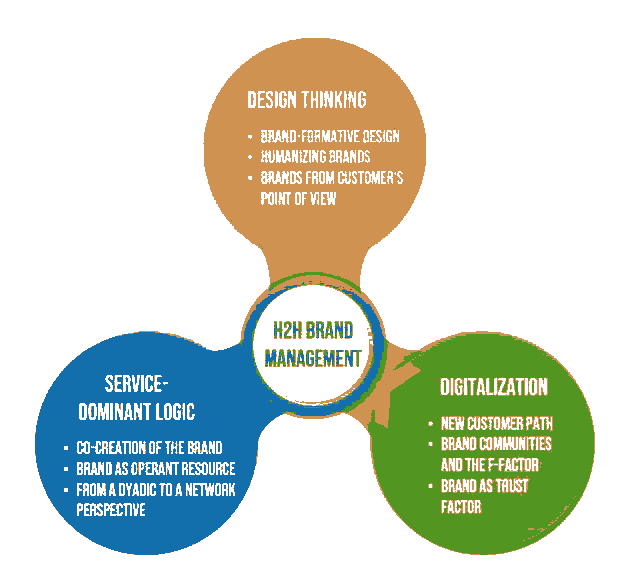

To overcome the current trust crisis of companies and other institutions like governments, NGOs, and the media, we offer a new Human-to-Human (H2H) Marketing model. H2H Management itself consists of different concepts that aim to manage trust as the key currency for companies embedded in highly interconnected ecosystems. Brand activism as a development accelerate of the CSR concept moves from “greenwashing” to “walk the talk” regarding sustainability and social responsibility. Knowing that only experiential and reputational trusts are manageable, H2H Management includes Customer Experience Management (CXM) and reputation management and integrates both parts into one Trust Model. CXM uses the 5 A model walking along the customer journey in order to design and manage the experience at each and every touch point along this journey from a customer’s point of view. Proactive expectation management is a key for reputation management and represents the next generation of public relations. The last core concept of H2H Management is H2H Brand Management. The CBBE approach, which is widely used today, is further developed based on the findings of Design Thinking, Service-Dominant Logic, and digitization in order to serve as an anchor of trust for people and communities. Brand meaning has to stick to a human problem and has to be co-created. Companies have to be aware of their limited options to determine the brand identity using the O-Zone concept. H2H Brand Management finally uses the Brand-formative Design concept to integrate design and marketing in the formation of brand meaning by designing customer experiences that fit to the context and needs of the customers.

Introduction

Trust has become the ultimate currency for marketing in today’s world. In this paper, we will focus on the strategic level of H2H Marketing, by putting special emphasis on trust management. Then we will illustrate the new thinking in brand management, basing both into the new theoretical framework – the H2H Marketing Model. This has implication for the new marketing in general and for developing a human-centered mindset. It enables the strategic and operative implementation of H2H Marketing.

Today, we are living in a Reputation Economy where trust is the lead instrument for doing business. The world is experiencing emotional, polarizing debates, with trust in governments declining dramatically in recent years. In a chaotic world of turmoil, people searching for guidance and orientation are increasingly looking towards companies and their leaders for guidance. Leading companies and their CEOs are expected not only to navigate business topics but also to address social, economic, and political issues. Company brand plays a special role because it can serve as a trust anchor, as a point of orientation. It can contribute to 2 Marketing Management and Strategic Planning 1544-1458-20-S2-82 establishing a trusting relationship between companies and customers, which is a top priority H2H Marketing.

Strategic H2H Marketing is divided into the two main pillars: trust management and brand management. They give companies the tools to create trust through various levers such as brand activism (outgrowth of CSR), Customer Experience Management, reputation management, and trust management.

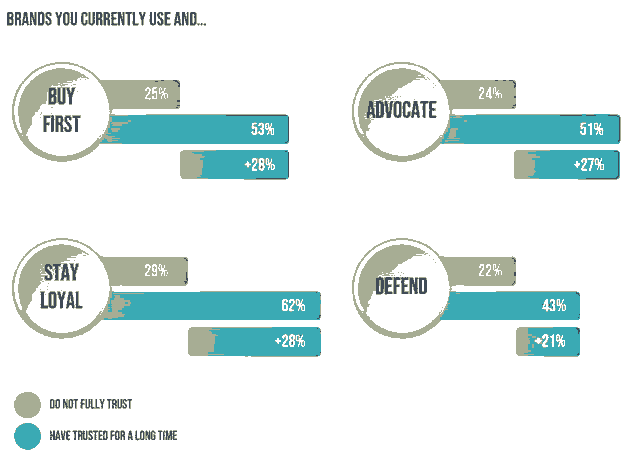

Trust has a positive impact on many different areas and is the breeding ground for loyalty and brand advocacy, essentials in the connectivity age where companies have lost direct control over their brands.

There is still an immense discrepancy between the promises made by companies in comparison with actual performance meeting expectations. Edelman in their 2019 Trust Barometer Special Report: In Brands We Trust found that 53% of respondents stated “[e]very brand has a responsibility to get involved in at least one social issue that does not directly impact its business,” while only 21% of respondents agreed with the statement “brands I use keep the best interests of society in mind.” Consequently, this chapter is intended to provide companies with tools and approaches on how trust can be fostered but also to act as a wake-up call for companies (see Figure 1).

The Big Trust Crisis: An Opportunity for Companies to Thrive

“We’re in a full-blown trust crisis”. This statement is not only a personal opinion; it can be backed by reliable data. In 2020, the Edelman Trust Study found the sharpest decline in general trust in the USA ever measure. 56% believe that capitalism in today’s form is not the right economic system.

The corona crisis improved the trust position of traditional media and many governments around the world. The phenomenon of disinformation is not new, but distribution of media has changed radically due to new technologies, so that the role of “gatekeeper” that professional journalist should have by conducting fact checks has weakened. Furthermore, today’s public not only acts as mere consumers of information but are actively involved as information producers, e.g., with blog posts or social media. Similar to developments in branding, we can also speak of democratization in the area of information production.

With such developments, it does not come as a surprise that the “loss of truth,” with 59% of respondents agreeing, was identified as main consequence of the downward trend of trust in media in the 2018 Edelman Trust Study. These societal changes in trust are accompanied by rising accountability from employers and expectations for businesses to lead the change. Building trust is the highest valued expectation (69% of respondents) people have for CEOs, while “64% […] say that CEOs should take the lead on change rather than waiting for government to impose it”. In 2019 this figure rose even further, from 64% to currently 76%. 71% of employees agreeing that CEOs should take a clear stand on employee-driven, as well as industry issues, political events, and national crises.

The employer is seen as a “trusted partner for change,” which verifies the importance of firms getting active on societal, political, and economic issues. The newest data shows that trusting a company to do the right things ranks among the top five buying criteria with 81% of consumers surveyed expressing its importance. This demand for commitment needs to be recognized by firms. Those who embrace these developments by actively engaging in brand activism can reap strategic and economic benefits from it, while others that stay quiet may suffer negative consequences. “In a highly polarized world, it’s no longer good enough to be neutral”.

H2H Trust Management in Practice

Rebranding may be needed for a company to stay alive, but it is not always successful. Yahoo disappeared despite great efforts of rebranding. After lagging behind, their attempts to catch up didn’t convince customers that they could be trusted again. Sometimes, it needs time and substantial investments to stay current and earn the trust of the customers again. BP (British Petroleum) tried to make their rebranding move to Beyond Petroleum, but the disaster of Deep Horizon impeded their effort, and the transition will take some time for British Petroleum.

A successful rebranding example is MasterCard, which is worldwide number two in the global credit card market. Although MasterCard is a hard-core money transaction business, they chose to adopt the slogan “money isn’t everything” and launched their campaign “Priceless…there are some things that money can’t buy. For everything else, there is MasterCard.” With that clever move, MasterCard distinguished itself from their big rival, Visa, as a more “human” company and doubled their transaction volume. Now, MasterCard is timely working on a “world beyond cash” to adapt to the new digitalized shopping world. The company is ranked very high in diversity and training of its employees and reputed to be a good company to work for. The future will show how MasterCard can keep up its brand trust by applying the H2H Trust Management concept. Raja Rajamannar, Chief Marketing and Communications Officer at MasterCard is working on this diligently since 2013 and knows that brand building never stops, particularly in coronavirus times.

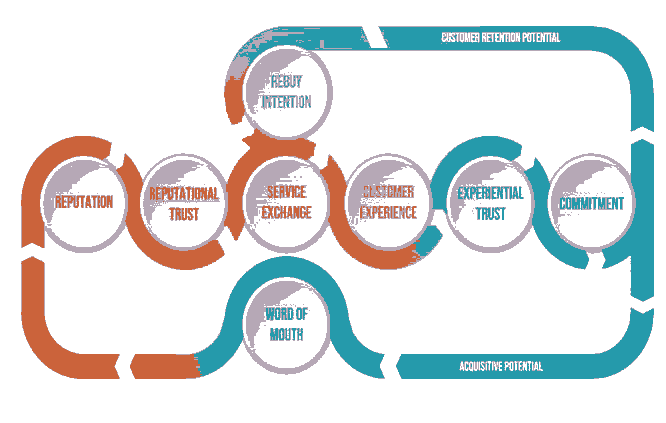

Trust management in H2H Marketing can provide solutions for current developments. Figure 2 shows the cause and effect relationships between brand activism (see Sect. 1.3), reputation, reputational trust, service exchange, customer experience, experiential trust, commitment, rebuy intention, and word of mouth as key variables of H2H Trust Management. Pfoertsch and Sponholz developed this model, which adapts and integrates several existing models and consistent empirically proved impacting factors on reputational and experiential trust. These empirically proved factors are for reputational trust: brand image, company’s size, and industry to which the company belongs. For experiential trust, these are communication behavior, conflict handling, cooperation, and solution orientation of the people directly involved in the customer experience. In addition, there are activities of the supplying company like relationship investments, customer integration, and the use of value-based pricing that impact experiential trust. Finally, customer satisfaction plays a key role in experiential trust. All these factors represent an action framework which helps the companies to reinforce trust in their brand. We added brand activism as an updated version of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives to the original model.

Three of all these concepts and factors are of special interest and will be examined in the course of this chapter: brand activism, Customer Experience Management, and reputation management (see Figure 2).

H2H Trust Management is based on a trust concept consisting of four parts: trust propensity, affective trust, reputational trust, and experiential trust. It is also based on the realization that only experiential and reputational trust can be “managed.” For this reason, the following chapter on trust management will highlight the relevant mechanisms for strengthening reputational trust through CSR and an integrated reputation management model and experiential trust through CXM.

As a response to customers firms are required to make societal progress happen and Corporate Social Responsibility needs to be rethought drastically. We are going to have a look at how firms, by doing well for society, can also do well for their shareholders. In the context of “democratization of the brand,” reputation management also gains importance. With more touch points to handle than ever (both online and offline), Customer Experience Management presents an essential pillar of H2H Marketing and will receive additional attention with the introduction of the Omni channel concept.

Brand Activism: Rethinking CSR

To consistently place people at the center of entrepreneurial activity means actively addressing their problems. For this, it is not enough to perceive Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as a compulsory exercise. It is not sufficient any longer to do well only for not looking bad. Far too long, CSR was used for publicly proclaiming and showcasing. A broad range of superficial assistance to social projects was given. This outdated approach to CSR may have worked in the past but is not suited for today’s world.

In 2018, brand activism was presented as a mature development of CSR to respond to new customer demands: “Brand Activism consists of business efforts to promote, impede, or direct social, political, economic and/or environmental reform with the desire to improve society”.

The integration of brand activism into H2H Trust Management follows the idea of strengthening reputation through activism for the good of society. At the same time, brand activism fits into our H2H Marketing Model because of its correlation to H2H Brand Management.

This kind of new thinking is urgently needed as research indicates that 66% of the American consumers surveyed consider it “important for brands to take public stands on social and political issues […]”, with social media being the medium of choice to demonstrate the firm’s position on these issues. Generation Z members are demanding even more. They are “a group of early adopters, digital natives and energized advocates”. From 2020, the demographic group of Gen Z will make up for four out of ten consumers, and it is this group that has the highest propensity (94%) to consider brand activism activities crucial and, more than previous generations, perceive companies as a collaboration partner to bring about change.

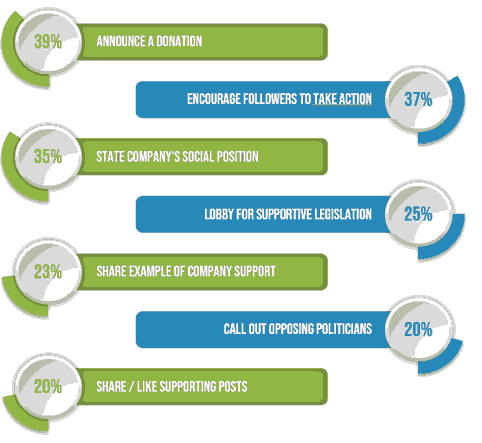

These developments come with an imperative for firms to act, which may trouble marketers and executives. But once understood, the new dynamics of brand activism can open a way to connect with the customers inside their communities, an area as discussed in the O-Zone model usually completely out of the firm’s reach. It gives brands the opportunity to engage in purpose and meaning-driven dialogue with customers, which comes with a major benefit – the interaction takes place in a social, non-intrusive way, fully in line with the Permission Marketing approach by Seth Godin. As the Sprout study shows: “Brands have an invitation from their audiences to get involved and the space to do it via social […]”. The 2017 Cone Communications CSR study takes it even one step further declaring that firms do “not only [have] the invitation, but the mandate to step up to solve today’s most complex social and environmental issues”. Moreover, with social media, there are various ways of getting started with brand activism (see Figure 3).

Marketers should ask themselves, “Does my firm live up to its mandate?” and “Is my firm actively engaged in activities that foster the greater good?” Some firms may experience a strong desire to get started but fear the consequences of brand activism going wrong. For those in doubt of brand activism, a look at the risk-reward ratio may be of help. Sprout Social found that the rewards for the brand outweigh the risk, as it was discovered that when consumers’ personal beliefs align with what brands are saying, 28% will publicly praise a company. When individuals disagree with the brand’s stance, 20% will publicly criticize a company”. Therefore, clear positioning on critical issues can serve as an effective driver of brand advocacy, since research indicates that positive brand advocacy will outweigh the negative.

Even negative advocacy can culminate in a positive result for the brand as the critique may trigger brand advocates that otherwise might have remained dormant. Moreover, with the connectivity that social media provides, firms have excellent ways to get started with brand activism.

Brand activism puts focus not on vision statements but concrete action. The term “activism” might indicate short-term thinking. We use it more in the sense of social involvement. Firms should look for wicked problems to tackle, putting human needs and desires at the center of attention. Customers will recognize and remunerate companies focusing on helping society and enable firms to thrive with the trust they gain along the way. As a positive example, we can bring up The Body Shop again, with its emphasis on natural ingredients and no animal testing. They are working towards a worldwide ban on animal-tested cosmetics. Even traditional companies like Unilever are increasing positive social impact and are leading in sustainability efforts. Some of them co-developed a circular business model that creates an infinite process circle for using resources most efficiently. Ernst & Young (EY) pledged to support “inclusive capitalism” to redirect investments into assets in better directions. Besides Ernst & Young, many other examples can be found in the publication brand activism.

Optimizing Results with Customer Experience Management

The well-cited article “Welcome to the experience economy” describes the evolution from a service to an experience economy in which the customer experience receives increasing attention as commoditization of goods and services is leading to the erosion of business models. Now, more than 20 years later, good Customer Experience Management (CXM) is more critical than ever. With new channels online and offline, and the connected customer constantly switching between them, the customer experience has become more complex and dependent on a growing number of influencing factors. Effective CXM is crucial for fostering experiential trust, one of the manageable trust components.

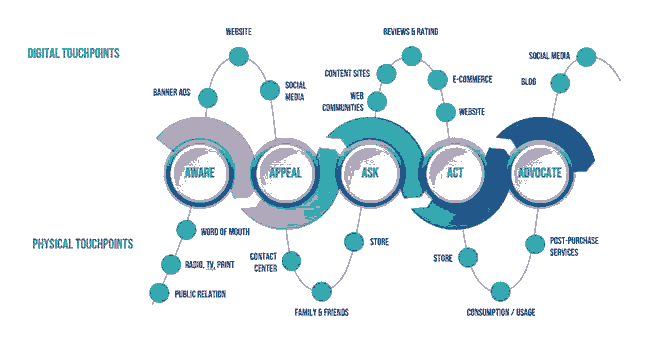

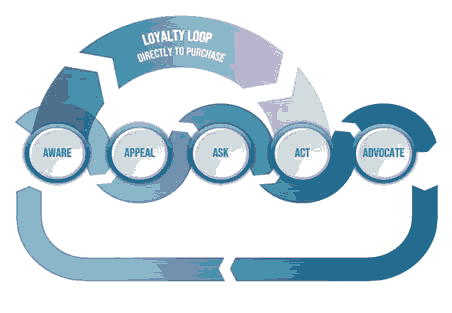

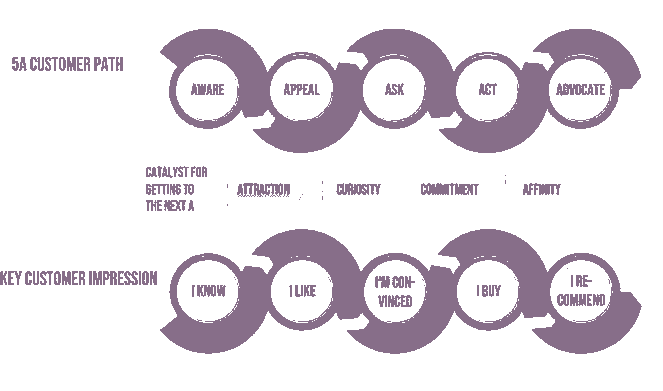

We should first define customer experience (CX) since it is quite an ambiguous term. “Customer Experience is the cumulative perception and reflection of all experiences from the single or multiple interactions of the customer with the contact points of a provider over the period of one or more exchange processes […]”. Mapping the whole customer journey along all touch points and channels can provide clarification for marketers to understand the complex CX better. Following the 5As framework (Aware, Appeal, Ask, Act and Advocate) introduced previously, several digital and physical touch points along the customer path can be identified. Figure 4 provides an overview of typical touch points.

The constant switching and interplay between on- and off-line channels and touch points that are controlled by the firm and those that lie outside of the firm’s influence sphere creates demanding challenges for firms who want to provide a seamless experience across all channels and touch points. The touch points shown in Figure 4 display the shifts in customer behavior that leads to the new customer path. For example, individual purchasing decisions increasingly are being determined based on the opinion of others, which manifests in the touch points of the ask phase, e.g., web communities and reviews/ratings, where “the customer path changes from individual to social”.

There is a great example for a B2B social media touch point enhancement. In 2013, Volvo Trucks placed a YouTube ad using Jean Claude Van Damme, a Belgian actor and retired martial artist, best known for his martial arts action films. The video demonstrated the precision of Volvo’s new dynamic steering system by having the actor perform his epic leg split, a stunt he is widely known for. This video elevated Volvo to a brand icon on YouTube. The company was able to improve its brand image and accelerate sales in the years to follow. Many truck drivers and truck owners who watched the video to see Van Damme became extremely interested in the precision driving solution of Volvo trucks. This is a very good example of the flexibility between physical and digital customer touch points. Potential customers use the enhanced transparency of brands that the Internet provides to revise product and service offerings thoroughly. This transforms the structure of the customer journey from a linear path into a customer cycle with iterative feedback loops. This is reflected in the 5A customer path that is not necessarily linear. Steps may get skipped.

For example, a customer might act out of an impulse without researching deeper, thus skipping the ask phase, while others might advocate a brand without actually buying it (e.g., luxury cars). The path can also take the form of a loop when customers jump back to previous steps as is depicted in Figure 5. The figure shows the concept of a spiral consumer decision journey introduced by Court, et al., in an article published in the McKinsey Quarterly, where the customer path starts with an initial set of brands, which then undergo active evaluation. To make for a consistent image, the consumer decision journey by Court was combined with the 5A customer path. After having decided which brand to buy, the post-purchase experience takes places.

Amazon is undoubtedly a great example for extensive post-purchase support. Since the post-purchase experiences are the most memorable part of the overall brand experience, Amazon follows up every purchase with emails and banners and product placements. IBM can be cited as a good industrial example. When they serve large companies or government institutions, they assign a customer relationship manager and have all digital interactions being adapted to the new business relationship situation. Starbucks rewards loyalty with referral programs using physical cards and digital interaction.

The circular decision journey has a peculiarity similar the 5A customer path. It does not cling to the classic funnel structure. It includes feedback loops that can even lead to expansion along the path instead of solely narrowing the options like a funnel. An example of this is the expansion of the initially considered set of brands after having evaluated other brands. To keep in mind is how crucial the interconnectedness of all steps is. A pleasant experience with a brand after the purchase including usage/consumption, post-purchase services can create advocates, which in turn publicly praise and defend the brand through positive word of mouth. Finally, it influences the probability of being in the initial consideration set of brands. Marketers must identify the customer touch points and the channels used in order to create an integrated across channels and consistent experience and allocate resources where they are needed most.

Build a Strong Reputation

Reputation has gained significance in the past years, especially due to unprecedented transparency and the lack of trust crisis that firms, governments, and media alike are suffering. The Reputation Institute in its 2019 RepTrak® 100 study assesses the situation as follows: “[…] companies are on trial in the court of public opinion. It’s a time of ‘reputation judgment day’ when companies are scrutinized on all aspects of their company—ethics, leadership, values, and beyond”.

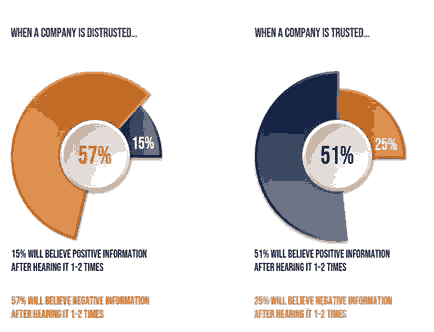

In the “reputation economy,” reputation and trust gained from taking on “the biggest and most urgent problems facing society” are an essential condition for success. Trust and reputation cannot be viewed separately, as recent analysis shows. The Edelman Trust Barometer study found that trust serves as a protective shield against reputational damage, by softening the impact of bad news while boosting positive reaction to good news (see Figure 6).

These findings point towards a clear assessment of the importance of building trust and reputation. Reputation has crucial strategic significance and is a task for the upper management where it should form a part of the overarching business strategy.

In current literature sources, there is no consensus on a uniform definition of reputation and the demarcation from other areas, such as brand management. It is imprecise, as reputation management relies on similar concepts such as the identity as the starting point and the images that stakeholders have as the basis for the resulting reputation. Image and reputation in this context need to be distinguished clearly: “[…] whereas image reflects what a firm stands for, reputation reflects how well it has done in the eyes of the marketplace”.

Reputation is the aggregation of the stakeholders’ images that result from congruencies and discrepancies between expectations and the firm’s offerings. Furthermore, images are more volatile as they are easily influenced by external factors, while managing reputation as the evaluated sum of all images requires a long-term commitment. Depending on the stakeholders, images of the same firm can vary substantially. While an armaments manufacturer may be an excellent firm in economic terms, thus a good image in the eyes of financial analysts, the public image of the firm and its products may be the opposite. However, what exactly determines excellent reputation management? For H2H Marketing we use the following description given by Cornelia Wust:

The central task of a systematic reputation management is, therefore, to build, maintain and protect the good reputation of a company synergistically with the identity, the brand and the image in the desired form, to achieve a positive attitude towards the company and its services, across all stakeholders, integrated and evaluated in the strategic, operational and financial goals of an organization.

She describes proactive “expectation management considering the relevant shareholders and is therefore subject to a permanent change process” as the core of reputation management. Therefore, firms should identify the exact stakeholders, their needs, expectations, and influence on the overall reputation to understand them and take actions to meet their demands.

For this purpose, the persona concept can be of good use, creating a stereotypical persona for each stakeholder group. In the form of a persona, firms can condense target groups of a service or product and stakeholder groups into concrete exemplary avatars that take into account the social environment, expectations, and desires of the different stakeholders. The concept is not scientifically grounded but is rather a useful method for better understanding customers and other stakeholder groups. “Although there is no common understanding in literature about the utilization of personas, all methodological approaches pursue the objective of obtaining a deeper understanding of users”.

In line with the S-DL, the exploration of the background of the personas can help to understand how the stakeholder groups co-create value with the firm. “Effective personas are based on the kind of information you can’t get from demographics, survey data, or suppositions, but only from observing and interviewing individual people in their own environments”. Getting this crucial context information can help in active expectation management and can be translated into the integrated reputation management model (shown in Figure 7).

In the model, the starting point is the identity values, in the forms of norms and actions of the company that is communicated to the stakeholders via communication specialists. Communication plays a decisive role in the process, and it is recommended to organize it “[…] a stakeholder relations team whose permanent task is to translate external expectations into internal measures and processes. Stakeholder management thus becomes a strategic task of corporate management”.

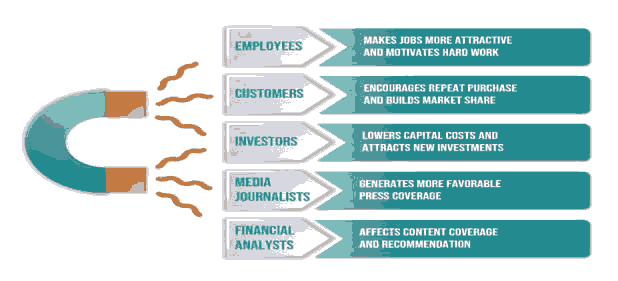

In summary, it can be said that reputation management is communication and expectation management of internal and external stakeholders and shapes reputation over a long period of time. Reputation needs values, norms, morals, and ethics as a basis for which the H2H Mindset provides guidance to help to translate these values and norms into words and deeds that put focus on action, not on mere words. And although reputation is difficult to measure and quantify in money terms, it definitely has an impact on the goodwill of a firm and therefore on its actual market value. “A good reputation acts like a magnet. It attracts us to those who have it”. This magnet effect on different stakeholders (as shown in Figure 8) can explain the economic value-creating function of reputation. For example, a good reputation will have positive consequences for the firm’s ability to raise capital from investors, which then can be used for creating real economic value through innovations and investment into market growth.

H2H Brand Management

H2H Marketing follows a highly integrative and collaborative approach. Consequently, the brand cannot be viewed separately but rather integrated into the subsystem of H2H Marketing. In the B2B Brand Management publication, we defined it as “holistic brand approach.” Now, the impact of the three influencing factors of H2H Marketing Model on the H2H Brand Management will be explored, and concrete strategic and operative tools will be presented to face today’s challenges in brand management.

The future of marketing and brand management is human-centric. In Marketing 3.0 human-centric marketing was introduced and in Marketing 5.0 expanded. Today, this is still considered the next evolutionary step after customer-centric marketing. The human-centric orientation is growing in importance in increasingly “inhuman” times, characterized by artificial intelligence, automation, robotics, etc., and brands need to adapt to this by becoming more human. “Human-centric marketing […] is still the key to building brand attraction in the digital era as brands with a human character will arguably be the most differentiated”.

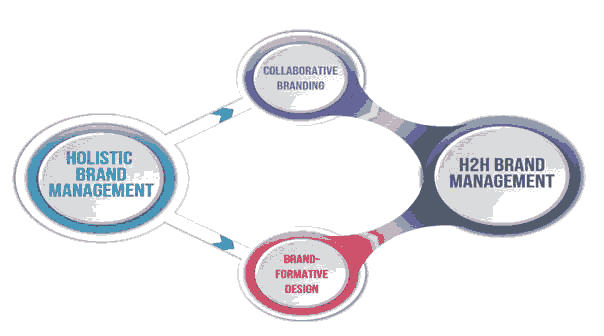

The newly proposed H2H Brand Management combines three components: holistic brand management constitutes the starting point to which the two pillars Brand-formative Design (BFD) and Collaborative Branding (CB) are added. Because BFD is a new multi-dimensional communicative means, integrating and creating feelings, emotions, associations or wants with consumers are an integrated part CB helps how a company can mobilize consumers' resources, engaging them in creative and innovation processes (as illustrated in Figure 9).

The holistic brand management had and still has the task to create a consistent and authentic brand on a regional, national, international, and global scale and to adapt dynamically to new environmental requirements in order to stay relevant as a brand. On this level, the company must strategically determine the brand identity and its value propositions to differentiate itself from the competition in the eyes of the customer, generating a brand image.

H2H Brand Management is closely linked to the H2H Process, constantly integrating and reacting to human insights, value propositions, content, customer access, and trust. At the operational level, the goal is the consistent implementation of the brand identity in collaboration with the customers and the integrated networks and communities. This co-creation of the brand is one of the essential innovations incorporated into H2H Marketing.

Furthermore, companies need to adjust to the new networked world where the control over the perception of the brand only partially lies in their hands while the word of mouth from friends and family or online community rating systems (the f-factor) is becoming increasingly important for purchasing decisions and brand perception. The third component is the brand-characterizing design where products, services, and experiences are designed from the perspective of the brand, taking into account product, customer, and context details.

Holistic Brand Management

When defining what a brand actually is, results are manifold. Following the classic definition of the American Marketing Association, it is described as “a name, term, sign, symbol, or design, or a combination of these, that identifies the maker or seller of a product or service”. Other definitions range from a brand being a promise or an emotional intangible concept of experiences to the sum of perceptions connected to a product or a firm. For this work, we will integrate both definitions and consider a brand as, “[...] a bundle of functional and non-functional benefits, the design of which from the point of view of the target groups of the brand, differentiates itself sustainably from competing offers”. This adds the inside-out view (brand identity orientation) to the outside-in view (brand image orientation). With this definition we combine the supplier view (brand identity) with the customer view (brand image), the intended benefits with the actual public perception of the brand. Thus, the brand becomes a customer-centric value proposition.

To understand the identity-based brand approach that goes back to Meffert and Burmann, a look at its principles is needed. The identity-based concept goes beyond the outside-in view. Instead of only finding customer needs and orienting the firm accordingly, the inside-out perspective, which analyzes the self-image of the brand from the point of view of all internal target groups, is also integrated. This self-image is the brand identity, consisting of the attributes that in the eyes of the internal target groups are characteristic to the brand. Opposite to the brand’s identity is the brand image as illustrated in Figure 10.

The brand identity can be actively developed and formed, the brand image, on the other hand, emerges time-delayed and only indirectly as a consequence of the brand identity management. The first step in creating a strong brand is the creation of a brand promise, condensing the brand identity to tangible, comprehensible statements about its utility. It should fulfil two functions: customer needs (brand needs) and a differentiation from the competition.

Under brand behavior, the product and service provision of the brand are understood as the behavior of brand representatives in direct contact with customers and all other contacts with the customer, e.g., advertisement. Inversely, the customer’s brand experience, which is the interactions between customer and brand, is reflected in the resulting brand image.

For the here proposed brand management to be successful, a high brand authenticity is needed to deliver brand experiences that fulfil the customer’s needs across all touch points. This means that the brand promise that was given and the actual brand behavior need to be in line. Otherwise, a bad brand image and word of mouth are to be expected. When defining the brand identity, the firm has to consider four constitutive characteristics, which are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Characteristics of Identity and Its Implications for Brand Management |

|

|---|---|

| Characteristic | Implications |

| Reciprocity | The brand identity only develops in comparing the own brand with other brands: Being in relation with others and differentiating oneself |

| Continuity | Maintaining the essential defining brand characteristics over time |

| Consistency | Avoidance of contradictions in brand appearance at all brand touch points and in the behavior of executives and employees of the brand. Ongoing coherent coordination of the essential brand characteristics |

| Individuality | Uniqueness of essential identity features compared to competing brands |

The four constitutive characteristics were derived from analyzing the identity concept of individuals, which is comparable to the brand identity concepts proposed in the identity-based branding. For brands, this means that differentiation from other brands, the relational interaction, is a prerequisite for building or changing a brand (reciprocity). Individuals search for continuity and tend to stick to essential characteristics over a long period of time. The same holds true for brands. Further, consistency is crucial; the internal identity and the outer image need to be coherent – “walk your talk.” Individuality on a personal level is determined in biological and sociological uniqueness. For brands, it is a conscious effort to achieve an individual brand perception. This is done either by underlining single, individual characteristics or by offering an individual combination of characteristics that would not necessarily be considered individual.

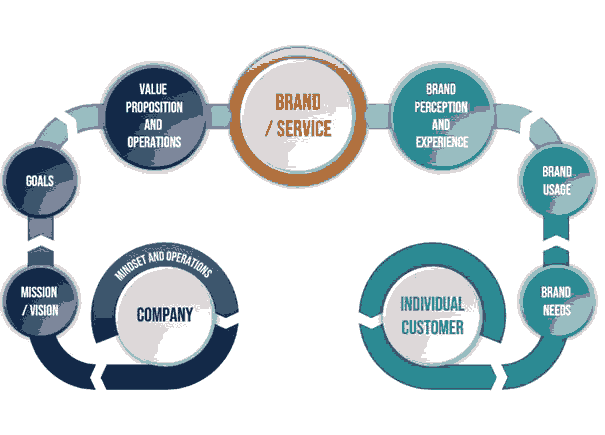

In addition, meaningful brand characteristics must be considered when the company defines its brand identity. According to H2H Brand Management, relating the brand to the solution of a human problem (H2H problem) is the best way to create a meaningful brand identity. The overarching brand strategy goals are derived from this process, and a specific value proposition for the customer is the result. The value proposition, as well as all operations on the brand touch points, should be permeated by the H2H Mindset. The value proposition of the brand could stand in contrast to its intended brand behavior, which then influences the customer-perceived brand image in the eyes of the customer. This image must be constantly reevaluated, depending on the brand experience on the touch points, as well as through brand usage. It must prove to fulfill the brand needs that initiated the interaction between the customer and the brand. In this process (see Figure 11), the brand serves as a mediator between the intended identity of a company and the brand image of the customer. The brand identity results from the vision and mission, corporate goals, value proposition, and operations of a company. The customer absorbs this through his perception and the experiences made with the brand and translates this into the use of the brand to meet his needs.

In the case of discrepancies between image and identity, adjustments must be applied to maintain consistency. An essential function of H2H Marketing is to build a brand that provides orientation and safety to stakeholders as an anchor in an increasingly dynamic, networked world. This is grounded on the understanding of customer processes and the resulting opportunities to gain insights that inspire and convince customers emotionally and cognitively, something we call digital anthropology. In this sense, H2H Brand Management is the ultimate form of communicative interaction.

Factor S-DL: Development of a New Brand Logic

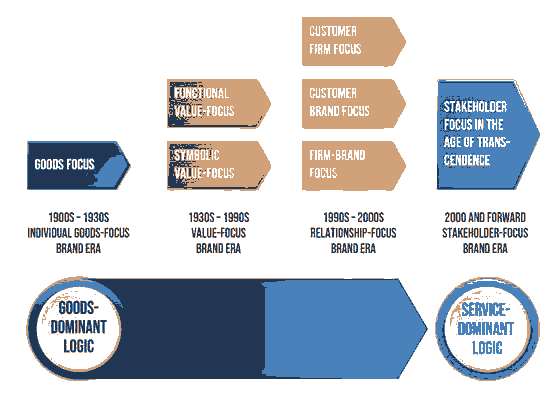

Parallel to the change from G-DL to S-DL thinking, branding has also experienced a shifting logic. Branding is at present considered a collaborative, co-creation process. The evolution of brand logic over time can be seen in Figure 12.

Branding in its early years was highly goods and output-oriented, and brands served as identifiers for customers to recognize goods visually. The customer had a passive role, as a mere recipient of value-in-exchange, the embedded brand value in the goods sold; thus together with the brand, he remained an operand resource – “resources on which an operation or act is performed to produce an effect”.

In the 1930s until the 1990s, brands became functional and symbolic images, from which customers gained knowledge about the brand’s capability to fulfill their utilitarian or symbolic needs. Brands focused not only on the functional (external) but also the symbolic (internal) benefits for the customers. This was arguably needed to achieve differentiation from competitors whose offerings were becoming increasingly similar. Brands were considered to be operant resources, which could be seen separately from the product offering. Customers remained operand resources to which the goods were branded. In the 1990s to 2000, the relationship-focus brand, “the general focus of branding switched from the brand image as the primary driver of brand value to the customer as a significant actor in the brand value creation process”. External customers and internal employees were now seen as participants in the increasingly interactive co-creation of the brand. Thinking shifted from viewing customers as operand resources, i.e., passive recipients to being considered as operant resources, active co-creators of brand value. This led to the determination that brand value changed from value-in-exchange to value-in-use perception of the customers. Abolishing the value-in-exchange perspective also had implications for strategic marketing. While before the Point-of-Sale received major attention, service and relationship building came into the spotlight, with brand value determined in-use after the purchase. This created the effect that “the time logic of marketing exchange becomes open-ended”.

Furthermore, a change from output orientation to process orientation took place. Firms’ employees were identified internal customers and as important drivers in the value co-creation, not only as makers of the physical product but also as service. Brands were now a promise to external customers with internal customers playing a crucial role. This internal customer perspective and the resulting focus on service are in congruency with the S-DL, “S-D logic […] suggests that it is the service experiences of customers that most commonly impact on brand value, through brand awareness and brand memory”.

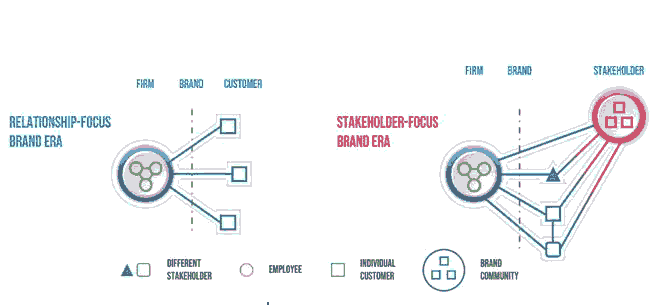

With the upcoming movement towards a network perspective, the dyadic relationship concept gets replaced by network relationships, connecting the firm with brand communities and other stakeholders and social relationships between customers or other stakeholders (see Figure 13).

Now that we have established that brands are co-created, what implications does this have from an S-DL point of view? Today’s brands are identifying, informative, and symbolic and have social interaction function. The various kinds of services brands offered to customers can be distinguished:

The Brand as a Service for Facilitating Information Processing

This kind of service is based on the identifying as well as the information function of brands. Products marked with a brand can be identified and distinguished more easily from other goods. This function has its origins in the time of strong product focus following the G-DL. S-DL constitutes a service to the customer, facilitating information processed during the purchasing process. In this context, the brand also offers an information function. Customers with previous experiences can use their knowledge (operant resource) to simplify information gathering and processing faced with complex market offerings.

The Brand as a Service to Influence the Customer’s Self-Concept

This kind of service goes back to the symbolic aspect of the brand, which can emerge from the firm’s marketing measures or be determined by external actors, the customers, the media, other organizations, etc. These co-created associations go beyond the functional value into the internal symbolic needs of the customers. The symbolic function is best seen in luxury goods. A customer buys a luxury car, not primarily for the functional benefit of transportation but rather for the symbolic association of the brand that the customer wants to transfer onto herself.

With the network perspective, brands now have a social interaction function, bringing customers together in different community groups. This can range from classic brand communities, where people share the same pleasure for a brand, to anti-brand communities, which collectively oppose a brand, to non-brand-focused communities, which shuns brands altogether. Thus, the brand’s service in terms of the S-DL lies in creating opportunities for the customers to socially interact and build relationships, whatever they may be.

At the beginning of this chapter, the concept of identity-based brand management, connecting the self-concept of the firm with the perspective of the customers, was introduced. In S-DL brand logic, this identity-based model needs to undergo adaptations, because it “implicitly treats the brand as an asset fully controllable by the firm”. It does not acknowledge the influence of the customers and their socio-cultural environment; it considers the customers only as an operand resources. Ballantyne and Aitken confirm this by pointing out that the identity-based approach “ignores the value-in-use derived from a product by a customer over time, and also the word-of-mouth communicative effects generated from within brand communities.” Additionally, there is an impetus for further developing identity, as the brand image is considered “dynamically constructed through social interaction”.

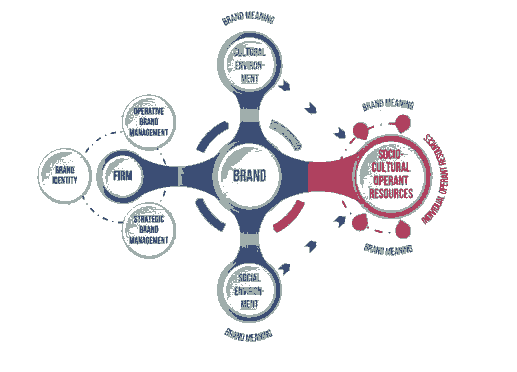

We support the work from Jan Drengner that proposes a holistic way of viewing brand management in accordance with the S-DL. On one side, the brand is seen as part of a firm’s value proposition; on the other side, it is seen as the socio-cultural context and interaction space of brands and customers that determine brand meaning. Under brand meaning, in this context, we understand it as the sum of individual experiences, associations, feelings, and behavior that generates a mental projection with an underlying meaning in the mind of the customer. As such, “brand meanings are socially constructed and in the public domain”.

To take these new considerations into account, we introduce a concept based on the S-DL that we call socio-culturally integrated brand management (shown in Figure 14), in which not the brand image is of interest, as in the identity-based model, but rather the brand meaning.

The brand identity in its intended meaning is still the starting point. The brand must offer a value proposition to the customers, who by using their operant resources attribute meaning to it. Customers with a similar socio-cultural background use similar operant resources to create value out of the value propositions. This may attribute coinciding meanings to a brand. The brand meaning is thus influenced by the socio-cultural environment, co-created under use of the customers’ resources and individually determined.

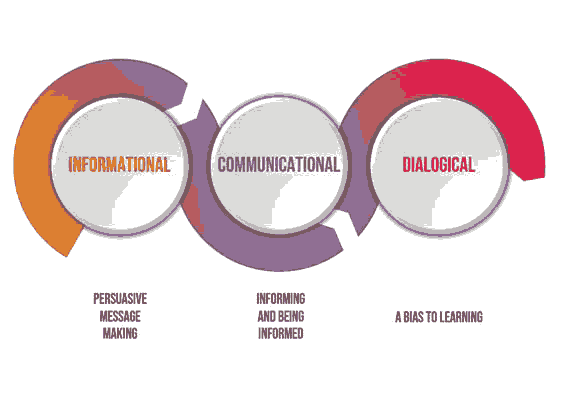

This implies boundaries in possibilities to influence brand meaning. Advertisement may have its limits when it comes to creating brand meaning, whereas trusted sources such as word of mouth coming from friends, colleagues, or family are considered more reliable. In times of co-created brand meaning, new forms of communication are needed (see Figure 15).

“We think it limiting to consider interaction and communication as separate processes. Any form of interaction between buyer and supplier acts as a source of brand meaning [...]”. In a service-dominant branding logic where customers are not passive receivers of one-way persuasive communication but, rather, interactive, co-creating resource integrators, communicational and dialogical interaction along all brand touch points should be embraced to successfully co-create brand meaning.

H2H Marketing thus takes the identity-based holistic brand management as its foundation, which then is expanded to include the findings of the S-DL. Brand identity should be designed and communicated in a reasonable way. It should also be clear that the brand image, respectively, brand meaning, is co-created taking into account the social-cultural context of the customers. Thereby, the brand becomes a service and fulfills a variety of functions.

Factor Digitalization: The New Customer Path in the Connectivity Age

In the last chapter, we talked about the changes in customer behavior and the relationship between firm and customer caused by increased interconnectedness. With the rise of digital channels, customers can constantly switch between online and offline channels (channel hopping) and are not easy to trace. Since customers’ expectations are also changing, firms look to multi- or Omni channel approaches to make a consistent customer experience across all touch points possible.

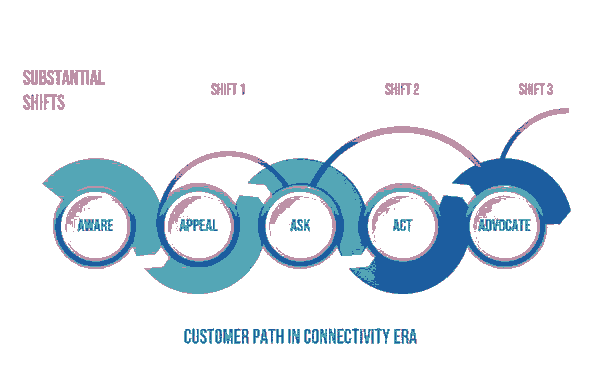

For customers, digital advancement has two consequences. Firms have the possibility to overwhelm customers with endless outbound marketing communication by sending emails, tailored online ads, etc. On the other hand, customers utilize more ways to search for information and are active via inbound marketing. They block intrusive communication measures and comb through a vast number of resources to find transparent information. A commoditization transforms value proposition models in many sectors. At the same time, the overexposure to stimuli overstrains customers and makes them look for other sources they can trust which they for customers, digital advancement has two consequences. Firms have the possibility to overwhelm customers with endless outbound marketing communication by sending emails, tailored online ads, etc. On the other hand, customers utilize more ways to search for information and are active via inbound marketing. They block intrusive communication measures and comb through a vast number of resources to find transparent information. A commoditization transforms value proposition models in many sectors. At the same time, the overexposure to stimuli overstrains customers and makes them look for other sources they can trust which they find in friends, colleagues, and family. With these new developments comes a new customer path, as shown in Figure 16.

In the pre-connectivity era, the understanding of people’s buying process was characterized by the 4 As: Customers become aware of a brand; then develop an attitude towards it, either positive or negative; decide how to act with purchase decision; and, finally, consider if they should buy again, act again. The 4A model is a typical funnel-shaped process, since with every step, the number of customers decrease.

With connectivity, fundamental shifts in customer behavior took place, which created the need for a new customer path, the 5 as (already shown in Sect. 1.4), to adequately map the buying process. Let’s have a look at these particular shifts:

Shift 1: Liking or disliking a brand (the attitude) used to be defined individually, while today, the social context of the individual becomes a deciding factor. In the connectivity era, the initial appeal of a brand is influenced by the community surrounding the customer to determine the final attitude. Many seemingly personal decisions are actually social decisions.

Shift 2 represents the changed meaning of loyalty and the target setting companies derive from it. While loyalty before was seen in the repurchase of a brand, in the connectivity era, loyalty is ultimately defined as the willingness to advocate a brand.

Shift 3 is found in the growing connectedness among customers ask-and-advocate relationships, which rely on other customers to find out more about specific brands. The feedback they get positively or negatively affects the appeal of the brand.

These three shifts lead us to the new customer path consisting of the 5 as. The path starts with the aware phase, in which customers know a brand as a result of past experience, marketing communications, and/or the advocacy of others. In the appeal phase, the customer then processes these impressions and develops attraction towards certain brands. He then tries to find out more in the ask phase about the brands he is attracted to by, for example, getting into contact with other customers or studying online reviews. If convinced, the customer may take the next step with act. This does not only include the purchase of the product but also other interaction such as filing a complaint in case of a negative experience or post-purchase services. The advocate level is the last phase and is considered the highest goal in modern marketing by the creators of the 5A approach (for a more detailed overview of the 5 A customer path, see Figure 17).

The high valuation of brand advocacy stems from customers increasingly turning to their social environment for information, rather than to the firms. The increasing digitalization is reinforcing this effect. In a world of increasing volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) brands serve more and more as trust anchors. The increasing digitalization leads to less and less direct contacts between employees of the branding companies and the customers. A humanized brand takes over this role of direct contact in a digitalized world. The effects of typical outbound marketing measures are declining, which is partly due to a typical paradox in today’s marketing. While customers today are more informed than ever, distraction, thanks to connectivity, is also at a record high. As the attention span and the time customers have for decisions decrease, while decisions to be made are manifold, they turn to the ones they trust for advice, which comes with substantial loss of control on the company side.

This process is described as the “democratization of branding,” essentially paraphrasing the Scott Cook quotation given at the beginning of the chapter, as they go on to state: “Technology-driven empowerment of consumers, such as the production of brand meaning by (micro) blogging, interaction in social networks or producing and disseminating brand advocacy, leads to new power relationships in both the commercial and non-commercial realms of branding”. Already in 2010, it had recognized the mode of action and the importance of brand advocacy inside social networks.

The influence that firms can have on brand communities and interpersonal communication is limited, which is why the loyal advocates of a brand come into play. When questions about a brand arise, there should be brand advocates stepping in to have a positive influence on the brand image and purchase decisions. Brand advocacy, another term for word of mouth, can be active, but only in rare cases, customers actively promote a brand. Otherwise, it can be prompted, by triggering. The two main triggers for prompted advocacy are negative brand advocacy or questions by others. In the light of this, negative advocacy from so-called brand haters is not to be considered a necessarily bad thing, as it can help activate advocates that might have remained inactive.

Going all the way towards brand advocacy, each step of the customer path is situated in different spheres of influence (indicated in Figure 18), a concept introduced as the O-Zone.

Getting closer to the personal center of the customer towards his own influence sphere, the influence of the brand diminishes. In the outer sphere, the firms are still in charge, managing the communication and touch points with the customer. Entering the others’ zone, communities and social contacts of the customers (the f-factor) are the deciding factors in influencing customers. Conversations inside communities, reviews, and rating systems, as well as advice from family and friends, are driving the purchase decision, resulting in a loss of influence on the side of the firm. The own influence is characterized as “a result of past experience and interaction with several brands, personal judgment and evaluation of the brands, and ultimately individual preference towards the chosen brand(s)” and is thus beyond any direct control of the firm.

The three spheres are interconnected and interact with each other. For example, a brand does an excellent job on its outer influence sphere by providing a convincing experience, which results in positive word of mouth to others that consequently affects the personal brand assessment and preferences of the customer herself.

Firms have a certain influence on the aware and ask phases, which lie at the intersection of the others’ and outer sphere, as well as exclusive influence on the brand appeal, while act and advocate are outside of the direct reach of the brand’s influence. Brands, therefore, must focus on the outer and partially the others’ sphere to affect the customers positively. Along the way from awareness to advocacy, there are catalysts that marketers can leverage to break up bottlenecks between the steps:

First Catalyst: Increasing Attraction

Various approaches are viable to improve a brand’s appeal. Brands with a human touch can make a brand more appealing to customers, since they are not perceived as robots without feelings but “a person with mind, heart and human spirit.” In concordance with what the S-DL dictates, brands should treat customers as an operant resource on an equal footing, as “equal friends”.

In addition to that, brand activism, meaning, taking a clear stand on current social, political, environmental, or economic issues, can strongly affect the brand appeal. Further focus should lie on the differentiation from competitors, for example, by offering customization or exceptional experiences, as Kotler et al. conclude: “The more bold, audacious, and unorthodox the differentiation is, the greater the brand’s appeal is”.

Second Catalyst: Optimizing Curiosity

Curiosity is the result of a discrepancy between the current and the desired state of knowledge. The true potential of creating curiosity lies in offering interesting information without being too revealing and thus demystifying the brand.

Third Catalyst: Increasing Commitment

At this point, the customers may be convinced of a brand, but there is still a way to go until the actual purchase takes place. For this to happen, firms need to provide a seamless experience along all touch points. As customers are constantly switching between online and offline channels, an integrating approach towards channel management is necessary, which can be found in Omni channel marketing.

Fourth Catalyst: Increasing Affinity

To successfully transition from the sole purchasing act to turning customers into loyal advocates, firms need to engage with their customers beyond the typical touchpoints. This can mean building a rewards and loyalty program and interaction on social media or using gamification to get into closer contact. Without question, the post-purchase phase is where, for customers, the moment of truth arrives: Does the product or service I purchased stand up to the pre-purchase promises given by the brand? The answer to the question has a strong effect on whether the customer develops an affinity towards a brand.

To conclude: There is an enormous increase in the importance of the customers’ social context in purchasing decisions, whereby brands have to give up a part of their power. This makes it all the more important for companies to leverage phenomena and tools like word of mouth, brand advocacy, and brand communities in order to benefit from these developments. The loss of control is a wake-up call for marketers, showing that it is no longer they who sit in the driver’s seat. Or in the form of a subtler hint, “Brand management should rather be a guiding activity, not a controlling one”.

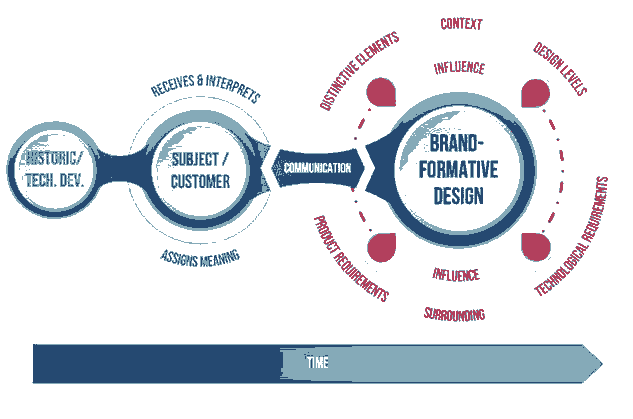

Factor Design Thinking: Brand-Formative Design

This subchapter puts emphasis on the interrelation of design and the brand. Usually, design is analyzed separately without recognizing the effect that convincing design can have on brands. As Of in his work on what he calls Brand-formative Design (BFD) lays out, design can have a differentiating function, especially in the eyes of the commoditization trend let loose by digitalization. Therefore, design can contribute to building a competitive advantage by offering differentiation and thus have strategic importance. He concludes: “Design can be a tool to create uniqueness, to communicate values, to entertain, to simplify selections and to create consumer satisfaction”. In this short statement, the parallels to the functions of a brand and the inseparability of both become evident. Delightful and refreshing design of products, services, and the whole customer experience can have strong positive effects on brand management. “Just one moment of unexpected delight from a brand is all it takes to transform a customer into the brand’s loyal advocate”. As was seen in the Design Thinking chapter, there is ambiguity in the somewhat subjective term design. The strict separation of marketers and designers is visible in the different understanding and practical approach to design and in the claims over its control that both parties express together with others, for example, engineers. While traditional designers may focus on physical or aesthetic aspects of a product, H2H Marketing adopts a broader perspective. In an experience-oriented society searching for meaning, the focus lies increasingly on the design of meaningful experiences rather than on the exclusively physical design of objects.

In the spirit of Design Thinking, interdisciplinary convergence is needed. “Marketers must acquire a better understanding of the design process and designers must acquire a better understanding of the marketing process”. Design products, or services, touch points, etc., need to be understood as “objects in the context of subjects”. A visual representation of the contextual incorporation of design is given in Figure 19.

The subject in this model refers to the recipients (consumers) of the designed object (product, service, etc.), which is evaluated differently depending on the specific context. What is noteworthy is the perfect coherence between Of’s model and the S-DL. The design does not in itself contain value but is received by the consumers, interpreted by using their knowledge and is finally assigned an individual meaning. Value creation in the S-DL is contextual value-in-context and experiential; the same goes for design. The effectiveness and the meaning of design are closely tied to its context. For example, the design of a gold-plated chandelier may be considered appropriate in a castle or a luxurious mansion but may appear absurd and pretentious in other circumstances. Also, the time factor is an important part of the context. A design which 20 years ago was considered outstanding may not evoke the same positive reactions today.

In the spirit of accepting customers as collaborating partners and moving the human being into the center of marketing, firms may also actively involve them in the design process of co-designing. For this, firms need to determine the role of the customer in the design process, at which stages he will be involved, and how big his scope of design shall be. While Jan Of focuses mainly on the customer’s involvement in the physical design consisting of packaging, logo, colors, etc., companies can consider at which other design points customers can be involved to better meet their preferences.

The work on BFD shows the importance that design has in the context of brand management that needs to be taken into account by marketers and people of other disciplines. As a practical recommendation, the iconic ten principles of good design by world-renown designer Dieter Rams can be helpful:

1. “Good design is innovative.”

2. “Good design makes a product useful.”

3. “Good design is aesthetic.”

4. “Good design makes a product understandable.”

5. “Good design is unobtrusive.”

6. “Good design is honest.”

7. “Good design is long-lasting.”

8. “Good design is thorough down to the last detail.”

9. “Good design is environmentally-friendly.”

10. “Good design is as little design as possible.”

Following these recommendations, allowing co-creation in the design process, as well as understanding the contextual nature of design meaning will help marketers create a positive outcome from the interaction between design and the brand.

Branding in H2H Marketing

H2H Brand Management builds on the Customer-Based Brand Equity Approach which is still relevant and key to brand management. Because of the impacting factors of the H2H Marketing Model, it has to be adapted today (see Figure 20):

1. The brand purpose as the key component of the brand identity has to be related to the human problem a company can solve authentically. The capabilities of the company that enable it to solve such a problem are key for the brand positioning process. Brand meaning is key to the brand identity. The promise and the proof to solve such problems load the brand with meaning for the involved and hopefully engaged stakeholders.

2. The brand personality has to be humanized and emotionalized to facilitate brand identity for the stakeholders.

3. The brand identity must be made dynamic by monitoring cultural changes and adapting the identity to these trends accordingly.

4. Companies must co-create the brand meaning with their customers and other authors from the outer zone. Brand communities (the f-factor and the O-Zone) have to be established and integrated into brand management and communication.

5. The brand communication has to be adapted from information to dialogue.

6. Trust, experience, and engagement have to be established as key performance indicators in brand management and have to be controlled continuously.

7. Companies should establish brand characterizing design as another dimension in the research and development process.

To overcome the big trust crisis, brand must be related to the authentic, human, and emotional promise of a company and/or product to solve a human problem effectively. This can be done either alone or even more authentically, together with other partners as a collaborate network. Only then, all stakeholders will trust a brand. The brand will become a trust anchor in a more and more destabilized environment. With the management approaches of CRM, CXM, CSR, reputation, service, and, finally, brand management, companies can develop and keep the trust they need to keep the brand relevant through the entire customer journey and help the customer to make their decisions. Companies need to keep their reputation management effective and create success stories with continuous reference streams as a magnet for all stakeholders. Liqui Moly is a traditional German brand from southern Germany, which could be used as an outstanding example. The company specializes in the production of fuel additives, lubricants, and motor oils and turned a commodity product supplied by huge international suppliers like ExxonMobil, British Petroleum, Chevron, or the most profitable company Aramco into a branded icon. With its full range, the company covers almost every wish of a motor enthusiast and is distribution to customers all over the world by OTV International. Liqui Moly oils and lubricants are used in cars, two-wheelers, commercial vehicles, construction machinery, boats, or garden tools. Whether for industrial, commercial, or private use, Liqui Moly products improve the service life of engines and units. The brand Liqui Moly has established very close relationship with all stakeholders through human-oriented management. Therefore, the brand is awarded almost annually as Germany’s most popular engine oil brand. The company’s products are highly regarded by both professionals and private users. They have a very strict code of compliance and show visible engagement for responsibility in and for the society (in German “sichtbares Engagement fur gesellschaftliche Verantwortung”). The product solutions ensure that wear and tear on the engine has little effect and that its mileage is guaranteed for years at a high level.

A holistic brand management which considers collaborative brand and brand characterizing design is the foundation for this kind of success. With the change from G-DL to S-DL, brand logic also evolved and created a human-oriented focus which includes all stakeholders of the firm in the relevant ecosystems. From there on, brands are socio-culturally interpreted in dialogical way of communication. Digitalization opened up new means of connectivity and created new consumer paths.

The new H2H Brand Management which incorporates Design Thinking, the Service-Dominant Logic, and digitalization give marketers of today a powerful tool to be more meaningful and relevant for the stakeholders. The future of H2H Brand Management is human-centric built on brand-characterized design and acting from a customer’s point of view. Together with the “humanized brand personality,” it becomes more human.

The Service-Dominant Logic added the co-creation of the brand meaning and the networking perspective and makes the brand to operant resource. With digitalization, new customer journey and multidirectional communication is possible to form the brand into a trust anchor. Following these recommendations, allowing co-creation in the design process, as well as understanding the contextual nature of design meaning will help marketers create a positive outcome from the interaction between design and the brand.

In our daily lives, we want to be surrounded by trust-worth brands. Yet, in the corporate world, only very few executives act accordingly. Many don’t know about the concept, and only some are able to know how to apply it. Its best application of H2H Brand Management could be found in the concept of B2B2C branding, mostly known as Ingredient Branding. It is an effective and proven strategy that assists B2B companies to step out of the shadows of anonymity and become visible to the end consumer. Brands that are well-known today have exemplified that with the help of Ingredient Branding differentiation. Ingredient Brands can distance themselves from competitors and enabling revenue and profitability growth. Large companies such as Intel, Huawei, and Microsoft have gained a competitive advantage. Also smaller companies like Gore Textiles, Schott Glass, and Recaro Seating applied the Ingredient Branding principle successfully and contributed immensely to their current success.

Aditya Birla Group is applying Ingredient Branding in their cellulose division Birla Cellulose with the Brand Liva and newly Livaeco. The Aditya Birla Group developed a playbook to create more H2H Brands within their group and reorient their corporate efforts for more human-oriented business. They wanted to create clarity about what Ingredient Branding is, which mechanisms it follows, and which advantages and disadvantages its application brings with it. Second, they wanted to deliver criteria to judge whether Ingredient Branding is a suitable strategy for its different businesses and, third, provide a clear step-by-step process how to put the theory into practice and accelerate the growth and profitability. Once implemented successfully, Ingredient Branding Management becomes important to maintain a favorable market position and provide human-oriented offerings.

References

- Adlin, T., & Pruitt, J. (2009). Putting personas to work: Using data-driven personas to focus product planning, design, and development. In A. Sears & J.A. Jacko (Eds.). Human-computer interaction: Development process. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 95–120.

- Ballantyne, D., & Aitken, R. (2007). Branding in B2B markets: Insights from the service-dominant logic of marketing. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 22(6), 363–371.

- Burmann, C., Halaszovich, T., Schade, M., & Hemmann, F. (2015). Identitätsbasierte Markenführung: Grundlagen– Strategie–Umsetzung–Controlling (2nd edition). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

- Cone Communications. (2017). 2017 Cone Gen Z CSR study: How to Speak Z.

- Court, D., Elzinga, D., Mulder, S., & Vetvik, O.J. (2009). The consumer decision journey. McKinsey Quarterly, 3, 1–11.

- Drengner, J., Jahn, S., & Gaus, H. (2013). The contribution of service-dominant Logic to the further development of brand management. The business administration, 73(2), 143–160.

- Edelman. (2011). 2011 Edelman trust barometer: Global report.

- Edelman. (2018). 2018 Edelman trust barometer: Global report.

- Edelman. (2019). 2019 Edelman trust barometer special report: In brands we trust?

- Fombrun, C.J., & Van Riel, C.B.M. (2004). Fame & fortune: How successful companies build winning reputations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Gaiser, B., Linxweiler, R., & Brucker, V. (Eds.). (2005). Praxisorientierte Markenführung–Neue Strategien, innovative Instrumente und aktuelle Fallstudien. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

- Godin, S. (2007). Permission marketing. London: Simon & Schuster.

- Haderlein, A. (2012). The digital future of stationary retail: On all channels to the customer. Munchen: Mi economic book.

- Halligan, B., & Shah, D. (2018). Inbound Marketing: How to Attract, Pick Up, and Delight Customers Online (D. Runne, Trans.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- Hansen, N.L. (2018, January 25). Dear CxO… Just focus on the customer journey!

- Häusling, A. (2016). Serie agile tools. Personalmagazin, 10, 36–37.

- Heinemann, G. (2014). SoLoMo–always on in retail: the social, local and mobile future of shopping. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

- Heinemann, G., & Gaiser, C.W. (2016). SoLoMo – Always-on im Handel: Die soziale, lokale und mobile Zukunft des Omnichannel-Shopping (3rd ed.). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

- Kemming, J.D., & Humborg, C. (2010). Democracy and nation brand(ing): Friends or foes? Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 6(3), 183–197.

- Kotler, P., & Armstrong, G. (2010). Principles of marketing (13th edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- Kotler, P., Hessekiel, D., & Lee, N.R. (2013). GOOD WORKS!: How the right marketing can make the world - and your balance sheets - better (N. Bertheau, Trans.). Offenbach: GABAL.

- Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., & Setiawan, I. (2010). The new dimension of marketing: From customer to person (P. Pyka, Trans.). Frankfurt: Campus.

- Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., & Setiawan, I. (2017). Marketing 4.0: Moving from traditional to digital. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., & Setiawan, I. (2021). Marketing 5.0 Technology for Humanity. Wiley.

- Kotler, P., & Pfoertsch, W.A. (2006). B2B Brand Management. Berlin: Springer.

- Kotler, P., & Rath, G.A. (1984). Design: A powerful but neglected strategic tool. Journal of Business Strategy, 5(2), 16–21.

- Philip Kotler, Waldemar Pfoertsch, Uwe Sponholz (2021) H2H Marketing: The Genesis of Human-to-Human Marketing. Springer, Heidelberg, New York January 2021

- Mayer-Vorfelder, M. (2012). Basler Schriften zum Marketing: Vol. 29. Kundenerfahrungen im Dienstleistungsprozess: Eine theoretische und empirische Analyse. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

- Meffert, H., & Burmann, C. (1996). Identitätsorientierte Markenführung. In H. Meffert, H. Wagner, & K. Backhaus (Eds.), Arbeitspapier Nr. 100 der Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft für Marketing und Unternehmensführung e.V. Munster: Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft fur Marketing und Unternehmensführung.

- Merz, M.A., He, Y., & Vargo, S.L. (2009). The evolving brand logic: A service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(3), 328–344.

- Of, J. (2014). Brand formative design: Development and assessment of product design from a future, brand and consumer perspective. Doctoral thesis.

- Oliva, R., Srivastava, R., Pfoertsch, W., & Chandler, J. (2009). Insights on ingredient branding. ISBM Report 08–2009. Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

- Pfoertsch, W., Beuk, F., & Luczak, Ch. (2007). Classification of brands: The case for B2B, B2C and B2B2C. Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Studies, 12(1). Jacksonville, USA.

- Pfoertsch, W.A., & Sponholz, U. (2019). The new marketing mindset: management, methods and processes for marketing from person to person. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

- Pine, II, B.J., & Gilmore, J.H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76(4), 97–105.

- Reputation Institute. (2019). Winning strategies in reputation: 2019 German RepTrak® 100 [Report].

- Rittel, H.W.J., & Webber, M.M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–165.

- Rossi, C. (2015, May 27–29). Collaborative branding (Conference paper). Paper presented at the MakeLearn & TIIM Joint International Conference, Bari, Italy.

- Sarkar, C., & Kotler, P. (2018). Brand activism: From purpose to action (Kindle edition). n.p.: IDEA Bite Press.

- Schafer, A., & Klammer, J. (2016). Service dominant logic in practice: Applying online customer communities and personas for the creation of service innovations. Management, 11(3), 255–264.

- Sherry, J.F. (2005). Brand meaning. In A.M. Tybout & T. Calkins (Eds.), Kellogg on branding: The marketing faculty of the Kellogg school of management (40–69). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Sisodia, R.S., Sheth, J.N., & Wolfe, D. (2014). Firms of endearment: How world-class companies profit from passion and purpose (2nd edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Sprout Social. (2017). Championing change in the age of social media: How brands are using social to connect with people on the issues that matter [Report].

- Tarnovskaya, V., & Biedenbach, G. (2018). Corporate rebranding failure and brand meanings in the digital environment. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 36(4), 455–469.

- Vargo, S.L., & Lusch, R.F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17.

- Vargo, S.L., & Lusch, R.F. (2016). Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 5–23.

- Vitsoe. (n.d.). The power of good design: Dieter Rams’s ideology, engrained within Vitsoe.

- Volvo Trucks. (2013). Volvo trucks – The Epic Split feat. Van Damme (Live Test).

- Weiss, A.M., Anderson, E., & MacInnis, D.J. (1999). Reputation management as a motivation for sales structure decisions. Journal of Marketing, 63(4), 74–89.

- Wust, C. (2012). Corporate reputation management – The powerful currency for corporate success. In C. Wust & R.T. Kreutzer (Eds.), Corporate Reputation Management: Wirksame Strategien für den Unternehmenserfolg (3–56). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.