Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 2S

How to Build a Brand: Inside an Indian Customers mind?

Mithun S Ullal, DOC, Manipal Academy of Higher Education

Iqbal Thonse Hawaldar, Manipal Academy of Higher Education

Vishal Samartha, Sahyadri College of Engineering and Management

Suhan Mendon, MIM, Manipal Academy of Higher Education

Anantha Padmanabha Achar, Kingdom University

Ankita Srivastava, Pandit, Deendayal Petroleum University

Keywords:

Marketing, Marketing Mix, Marketing Decision, Consumer Decision Making, Brand, Branding, Brand Value, Attitude, Brand Originality, Iconic, Sub- culture

Abstract

Purpose – All efforts of marketers are aimed at building brands. But there is no fixed formula to build a brand in Indian market. The purpose of this study is to identify the attributes that has the power to position the product in the Indian youth’s mind as a high-value brand and influences their buying behaviour.

Design/methodology/approach – The research is empirical in nature and data has been collected through focus group interview on the sample picked from North, South, West and North Eastern region of India.

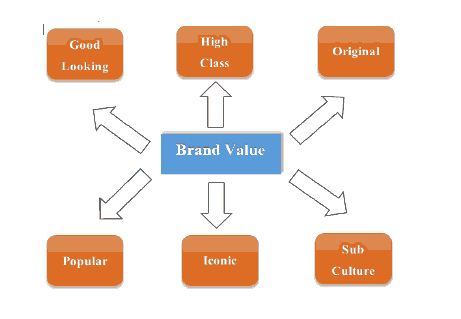

Findings – The study prove that the brand value is an integrative effect of Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and subcultural elements in Indian market that which distinguish high and low-value brands. These elements vary but are closely knit together forming a higher-order structural model of brand value.

Research limitations/implications – The direction for future research and limitations of the study are presented.

Practical implications – The study provides the roadmap to managers as to how to build a high-value brand in Indian market. The study will be helpful to the companies in designing their marketing programs to establish them as a high-value brand and will also benefit the companies with low brand value in repositioning their brand as a high-value brand.

Originality/value – The available literature agrees that high-value brands are associated with narcissism, pleasure, excitement and youthfulness which make a brand succeed but these studies are lacking in defining these characteristics clearly and hence the concerns of high-value is unanswered. Under this study these gaps in literature are addressed.

Introduction

As the fastest growing economy today, India is home to a fifth of the world's youth. Half of its population of 1.3 billion is below the age of 25, and a quarter is below the age of 14. India’s young population is its most valuable asset and most pressing challenge. It provides India with a unique demographic advantage. Indian youth spends on Brands which gives them value. According to economic times, the top brands in the minds of the youth in India are Coca cola, Apple, Diesel, Nike and McDonalds. Those brands which are successful in creating that value in today’s customer’s mind gains in the market whereas those who fails to understand the mind-set loses the race. Millennials are known to be independent-minded and headstrong about their purchase decisions. Marketing to this demographic is quite a challenge. It takes time for brands to cater to a wider customer base which makes it look more iconic and popular but less valued like café coffee day and McDonalds in India.

Identifying the Brand Value

High brand value is associated with its pride and uniqueness. The value is mainly driven by many factors such as its subjectivity with which it is perceived (Gurrieri, 2009). The characteristics driven by subjectivity of the customer helps in identifying them. Also, the valence in case of a high-value brand is positive (Mohiuddin et al., 2016). Which command admiration and acceptance. They are useful and desirable (Runyan et al., 2013) and of luxury (Bhat & Lee, 2015).

A high-value brand in the minds of the youth in India goes beyond being just desirable (Pountain & Robbins, 2000). Also, youth associate a brand with independence as they want to be rebellious and expect no rules and restrictions (Warren & Campbell, 2014). This independence needs to be observed as to how a person deviates from the regular norms of a society (Brun et al., 2016) and are unperturbed in the face of hostility (Hodis, 2010; Ullal & Hawaldar, 2018). Sometimes discount offered by the company affect brand image (Hawaldar et al., 2019). The element associated with a high-value brand can change with business time. Both the types of brands, one which is popular among the initial innovators and the second which is accepted by other are termed high-value brands by the Indian youth (Warren, 2010; Ullal & Hawaldar, 2018).

Problems to be Solved

We know that high-value brands are needed (Mohiuddin et al., 2016) independent (Frank, 1997) but what is being needed and independent is different in different people’s opinions. There is no blueprint for brand building (Warren, Batra, Loureiro & Bagozzi, 2019). Some brands in India tried to position themselves as high-value brand and were competitively priced and tried to be popular. No literature was found during the research which defines these elements. Studies shows that high-value brand are associated with narcissism, pleasure, excitement and youth (Bird & Tapp, 2008) but does not define these characteristics clearly. This brings us to the first gap of this study

What Elements are Ideal for a High-value Brand?

Next, we find out the measure of brand value in certain product categories (Sundar Tamul & Wu, 2014) as there is no fixed scale developed to find the brand value. Developing this scale will help marketers identify their brand’s value and if the brand value is low what needs to be done. So next gap we address is

To Develop a Scale to Identify the Elements of High-value Brand

Literature shows that being a high-value brand makes the marketer succeed (Belk, Tian & Paavola, 2010) but the concerns of high-value is unanswered. Do customer prefer to spread word of mouth about high-value brands, how much are they willing to pay are the questions. This brings us to the third gap

What are the Results of Having a High-value Brand?

Next, brands are lively and energetic (Heath & Potter, 2004), but the journey of this liveliness and energy are not traced in any of the literature. The acceptance of innovators is necessary for acceptance by a larger set customer is proven in the literature, but the gap is in how the elements and its properties contribute to the journey of the brand through the product life cycle is missing. This brings us to our fourth question

How Does the Elements and its Properties of Brand Value Change Over Time in its Product Life Cycle Journey?

The above-mentioned gaps in literature are addressed under this study and become our Research Questions.

Elements Identification

Based on grounded theory, we try to find the elements of a high-value brand. To find this, focus group, interviews and write ups were used. India has multiple cultures. Universities across India was selected to get a sample which diverse across different cultures. Representatives of 28 states were selected for the study. Patterns were identified across all three methods of data collection (Goulding, 2000). The recorded units were organised using comparison method across various sets of data. Axial coding was used to explain the relationship between these models. These models and units were put in order into different themes. All the types of studies are described along with their themes.

Methodology

The focus group interview was conducted on North Indians, South Indians, West Indians and North Eastern Indians. There were 6 participants in each group. Followed by 24 depth interviews with the youths in Manipal University, India. The interview was conducted based on the methodology suggested by Gubrium & Holstein (2001). The question asked was “what are the elements do you associate with a high-value brand”. The respondents were asked to describe high-value brands in 25 words. Second question was about which brand they thought was not having high brand value and why?

Patterns in the Data Collected

Multiple themes emerged on high-value brand from the three methods. First the respondents see high-value brands as good looking, high class, original, iconic, popular and subculture. All the elements and its association with high-value brand is shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Meaning of the Elements of High-Value Brand |

||

|---|---|---|

| Element | Meaning | Citations |

| Good looking | Pleasing on the eyes | Dar-Nimrod, et al., (2012), Runyan, Noh & Mosier (2013), Sundar, Tamul & Wu (2014), Bruun (2016), Caleb Warren, Rajeev Batra, Sandra Maria Correia Loureiro, and Richard P. Bagozzi (2019) |

| High status | Sophisticated and prestige | Connor (1994), Heath & Potter (2004), Belk, et al.,(2010), Caleb Warren, Rajeev Batra, Sandra Maria Correia Loureiro & Richard P. Bagozzi (2019) |

| Original | Unique and creative | Read, et al., (2001), Runyan, Noh & Mosier (2013), Sundar, Tamul & Wu (2014), Warren & Campbell (2014), Bruun et al., (2016), Mohiuddin, et al., (2016), Caleb Warren, Rajeev Batra, Sandra Maria Correia Loureiro and Richard P. Bagozzi (2019) |

| Iconic | Cultural symbol | Holt (2004), Warren and Campbell (2014), Caleb Warren, Rajeev Batra, Sandra Maria Correia Loureiro & Richard P. Bagozzi (2019) |

| Popular | Fashionable and liked by many | Heath & Potter (2004), Dar-Nimrod, et al., (2012),Rodkin, et al.,(2016). |

Good Looking

Youth described high-value brands as good looking which meant the brands looked aesthetic and were pleasing on the eyes. Two of the respondents said they considered BMW a high-value brand because of its aesthetic look, both on the outside and the inside. Another referred to Prada as always in fashion because of its looks. The theme that high-value brands are good looking agrees with the previous research that there is a relation between perceived good looks and the elements that are desired by the youth (Bhat & Lee, 2015). Some respondents considered brands like Omega awesome because of their looks. The finding the high-value brands are very good looking joins the literature that show the positive valence (Belk, Tian & Paavola, 2010).

High Status

The Next recurring theme was that high-value brands are of high status. Lexus is of high status because of its elegance and the customers who drive them. The high status of other brands like Nike, Louis Philippe were of high-value across various industries. High-value brands have high status is consistent with the previous findings across various segments (Ullal & Hawaladar, 2019). The next theme about high-value brand is that it is original. The youth perceive high-value brands to be authentic and generally original. This originality makes them feel high and satisfying which helps the brands in connecting with the customers. Brands such as Rolex and Swatch are original, and lot of fake copies only make the original look highly valued and desired by the youth. It is the exclusiveness which makes up the originality. This is consistent with the literature provided by Warren & Campbell (2014). None of the previous literature has identified originality as a characteristic of high-value brand.

Iconic is a trend identified in all the three types of techniques. Being unique, being associated with the rich, glamorous all added to the iconic status of the brand. Jaguar was considered iconic brand because of its association with the rich people and its uniqueness in the market. Not everyone can own a Jaguar. There exists a strong link between high-value brand and rich people which make the brand look iconic (Warren, 2010). Respondents saw high-value brands as having high status.

Popularity was another theme in responses that made high-value brands desirable. Though ownership of Mercedes was exclusive, but the brand was popular among the masses in India which consisted of most people not being able to buy it still admire it. This was well articulated in the write up part of the survey as people considered high-value brand as very popular. Increasing these characteristics makes a brand value high (Warren, Batra, Loureiro, & Bagozzi, 2019).

Sub Cultural

High-value brands were associated with western countries (Hebidge, 1979; Schouten & Mc Alexander, 1995). Youngsters believe that using high-value brands made them feel to be a part of the western culture which is highly valued in India. Youth associated high class brands with different European and American countries and would like being part of that sub-culture. When accepted by a large number of customers, brands like McDonalds maintain their subculture. The research outcomes consistently show that in music, clothing’s, mobiles and laptops were perceived to be different from others (Danesi, 1994; Mailer, 1957; Thornton, 1995).

High-value and Low Valued Brands

The regularity of occurrence of these themes was noted down in the third writing experiment. 120 writings observed each of the 6 themes prop up for high-value and low-value brands multiple times. The high level of the element is noted as 1 and if not it is coded as 0.

The write showed that 83% of the respondents said high-value brands show high class. It was associated with the success and the elite of the society. They stood for the success in their profession and only 6% of the low-value brands were described as high status with w2 ¼ 61.47, p<0.001. 89% of respondents said that high-value brands were popular and majority of the low- value brands were also popular but with lower class people w2 ¼.67, p ¼.48. Further certain elements were used by the respondents to differentiate between high-value and low-value brands. High-value brands were most of the times described as being part of a subculture (52% vs. 9%; w2 ¼ 31.12, p<0.001), good looking (34% vs. 2%; w2 ¼ 21.78, p<0.001), original (44% vs. 5%; w2 ¼ 24.15, p<0.001), popular (21% vs. 5%; w2 ¼ 8.12, p<0.009), iconic 11% vs. 1%; w2 ¼ 7.32, p<0.01) than low class brands. The other two research techniques also described similar characteristics about the high-value brands as shows in Figure 1.

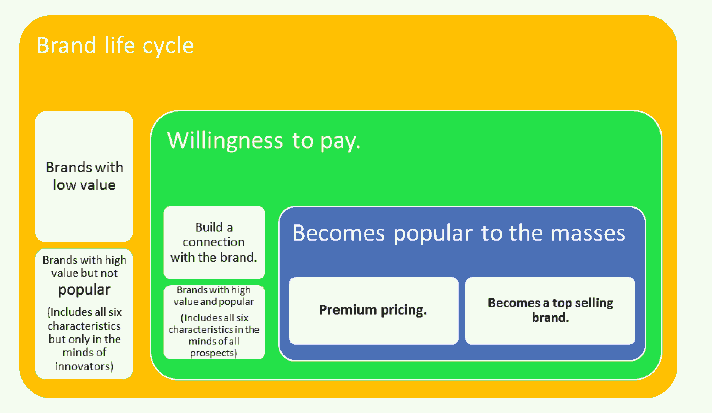

Brand life cycle

Brand life cycle

Brands with low value

↓

Brands with high-value but not popular (Includes all six characteristics but only in the minds of innovators)

Outcomes:

Willingness to pay.

Willingness to say.

Build a connection with the brand.

↓

Brands with high-value and popular (Includes all six characteristics in the minds of all prospects)

Outcomes:

Becomes popular to the masses.

Premium pricing.

Becomes a top selling brand.

Themes that were not Found

The high-value of the brands was mainly due to the lack of knowledge about the subcultures (Danesi, 1994). The efficiency and desirability elements described in the literature were not found in the outcomes of our experiment (Dar-Nimrod et al., 2012; Horton et al., 2012; Pountain & Robins, 2000; Warren, Pezzuti & Koley, 2018). These elements were needs searched in humans as the mentioned six elements already described (Fiske, Cuddy & Glick, 2007). In humans and brands certain elements are considered desirable but these elements differ for humans and brands. The personality and elements of human vary across both (Aaker, 1997; Batra, Ahuvia & Bagozzi, 2012).

Nomo Logical Modelling and Structural Modelling

Multiple surveys were conducted to analyse the structure of elements of high-value brands that were outcomes of the research and to test nomological relations with the concepts. Every research started with naming three brands by respondents which they considered to be a high-value brand and low-value brand. Initial 3 tests were focussed on developing the measures for the models. Next 3 tests found the structural measurement models for the six elements and also to check if all six elements were associated with high-value brands along with establishing the relationship among the concepts and the brands. The next set of studies focussed on accurate measurement of high-value brands and to identify to what level the brands are associated with these 6 elements. Also, the next test was an assenting design to reproduce the outcomes of the previous tests. Last two tests repeated were to identify the subjectivity associated with high-value brands as to how different are they among innovators, thinkers and how are they with mass markets among the Indian youths.

Research Methodology

Test 5 (N ¼ 400; 50% male; modal age ¼ 21) and test 6 (N ¼ 400; 51% male; modal age ¼ 23) recruited youths from leading universities in India for an online survey. Test 7 respondents were IT professionals (N ¼ 429; 52%male; modal age 24–25 years) from the Bengaluru and NCR. Test 8 had 250 respondents who used fashion brands and were in age group of 16-19 and 61% male.

Selections

Every test had a minimum of three brands to be evaluated. Test 5 and 6 respondents had to pick high-value brands and brand which actually they used but considered to be low-value brand. In test 7 respondents identified high-value and low-value brands and test 8 brands were listed as high-value luxury brand, low-value fashion brand and widely used high-value brand and respondents were asked to identify those brands.

Measuring Brand Elements

After all the brand names were named in the tests rating the brands was done based ordinal scales. Based on existing literature and pre-tests conducted we have listed 50 brands to identify to what extent these brands have been observed to be good looking, iconic, subcultural, original, popular, and high status. The following studies were aimed to identify which brand surprisingly captures the concept of high-value brands than the extent to which it seems better if 5 more new items are introduced replacing the existing few items. Next few studies used all the 50 brands to identify the extent to which the brand seems more than the other aspects like being valuable along with other 6 elements.

Measuring all the Concepts

Various concepts in the literature were measured about high-value brands. All the tests were used to measure how much did the youth love their brands (Batra, Ahuvia & Bagozzi, 2012), how are you connected to the brand (Escalas & Bettman, 2003), what they speak about the brand in public and social media and what are willing to pay for a brand. Test 5, 7 and 8 measured the general thinking about the brand in the minds of the respondents. Tests 5 and 7 measured the various dimensions of the brand using the scale developed by Aaker (1997). Tests 7 and 8 measured how well the respondents know he brand and its familiarity and how much price does it command. Satisfaction about the brand was measured by in test 5 using the scale developed by Netemeyer (2004) and pride of using the measure developed by Tracy & Robins (2007).

Checks on Tests

Test 6 and tests 8 tested the how every brand was perceived by respondents individually. Tests 7 and 8 were based on how respondents think about what others in the Indian market though about the brand. Test 8 measured what respondents think about the brand before and after the tests.

Individual Differences Measure

Tests 8 measure respondents need to stand out (Ruvio, Shoham & Brenc, 2008). All the tests finally measured the demography which did not affect the results. Test 7 and 8 included all the variables used for a methods factor tests.

Model for Measurement of Brand Value

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted on pre-tests and confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on test 5 to test 8. Items were replaced if they loaded onto multiple factors (Hair et al., 2006) based on literature review. A reflective model was used as it was more appropriate for measuring brand value. The final model consisted of two factors, that being desirability of the product and the independence. All six elements loaded on to these factors equally. Brand desirability and the independence are high order factors associated with a brand. The structural coefficients are shown in Table 3 derived from test 5-8. Standardised coefficients for high and low-value brands are shown in a group. Study 5 used three elements measuring whether the brand is valued and in the following studies, these elements were replaced by 5 elements to measure if the brand was better than others in its category.

Model structures were consistent in all tests which are shown in Table 3. Variance and composite construct reliability were between 0.6 and 0.8. Equivalence of measurement were found to be equivalent. The differences observed were minute and due to journey of the brand from innovators to thinkers.

All the tests had excellent fit. Tests 6 to 8 also had good fit satisfying tests of adequacy. In tests 5 to 7, elements of high-value brands were averaged at 0.92. For low-value brands, it was ay 0.96. The factor loading from the first to second was averaged at 0.98. From second to higher-order brand value was averaging 0.91 for good looking, 1.01 for high status, 0.93 for original, 0.69 for popular, 0.71 for iconic, 0.66 for subculture.

Comparison of High-value and Low-Value Brands

The nature of brand value in our model differentiated between high-value and low value. Paired sample t-test for both the types of brands showed that six elements loaded to high-value brands more than low valued ones (ps<.001). Some brands noted as high-value was surprisingly noted as low valued by other respondents. The fact that tests 5,6 and 7 differentiated between high and low valued brands showing its bias. Study 8 on a specific luxury segments also agreed upon the previous test results as shows in Table 2 and Figure 2.

| Table 2 Outcomes of Tests |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | Study 4 | Study 5 | Study 6 | Study 7 | Study 8 | |

| Sample | 750 | 750 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 75 |

| Brand value | High | High | High & low | High & low | High & low | High & low | High & low | High unpopular, High popular, Low |

| Characteritics | Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. | Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. | Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. | Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. | Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. | Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. | Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. | Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. |

| Correlates | Nil | Nil | Nil | Brand character | Brand character | Nil | Brand character | Nil |

| Outcomes | Nil | Nil | Brand relation and attitude | Willingness to pay and say | Willingness to pay and say | Willingness to pay and say. Brand relation. High price. | Willingness to pay and say. Brand relation. High price. | Willingness to pay and say. Brand relation. High price. |

| Differences | Same | Same | Same | Same | Same | Same | Same | Regular users of fashion brands. |

The Truth about High-value Brands

The first few elements measured in test 6 as to how extraordinary the brands were and how valuable they were. The test 6 measured all the elements of the high brand value. The model fit statistics for new elements added were same as previous elements selected. Lamda coefficients were found to be moderately high for all the brands listed. From extraordinary to valuable factors, structural coefficients were high for the elements added than the existing elements which increased from 0.84 to 0.89 for high-value brands and from 0.91 to 0.96 for low-value brands. Taking this outcomes and conceptual findings in favour of this finding (Belk, Tian & Paavola, 2010) replacements were done.

Proof of High-valued Brands from Concepts

Brand love is different from how people see and connect with brand. Brand value lies in the way customer perceive but how they see and connect is the response triggered towards them which show that it is result of brand value. Brand value is differentiable from liking and connectivity as brand value is more than just liking (Warren & Campbell, 2014)

Empirical Evidence

The test 5,6,7 and 8 tested discriminant validity based on psi correlations among variables to test if 95% confidence interval fell below 1.0 (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012) as shows in Table 3.

| Table 3 Factor Analysis Model Coefficients |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 5 | Study 6 | Study 7 | Study 8 | ||||

| Measurement Model | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Both |

| Good looking | n ¼ 750 | n ¼ 750 | n ¼ 250 | n ¼ 250 | n ¼ 250 | n ¼ 250 | n ¼75 |

| Beautiful | .60 | .71 | .74 | .82 | .76 | .83 | .84 |

| Attractive | .61 | .81 | .74 | .81 | .77 | .84 | .85 |

| Good Design | .75 | .81 | .82 | .84 | .72 | .83 | .82 |

| Appearance | .72 | .79 | .81 | .85 | .74 | .82 | .81 |

| Original | |||||||

| Is new | .61 | .73 | .68 | .71 | .59 | .69 | .72 |

| Is original | .48 | .56 | .72 | .68 | .72 | .71 | .78 |

| Unique | .52 | .56 | .72 | .68 | .72 | .71 | .78 |

| High class | |||||||

| In demand | .70 | .73 | .62 | .74 | .52 | .64 | .61 |

| Exciting | .81 | .78 | .79 | .81 | .81 | .78 | .73 |

| Complex | .69 | .72 | .68 | .76 | .69 | .65 | .69 |

| Popular | |||||||

| Likable | .62 | .71 | .65 | .71 | .66 | .77 | .74 |

| Fashionable | .64 | .75 | .78 | .79 | .61 | .42 | .65 |

| Loved | .72 | .69 | .67 | .75 | .65 | .71 | .71 |

| Subcultural | |||||||

| Differentiable | .72 | .62 | .78 | .74 | .74 | .82 | .72 |

| Unusual | .75 | .74 | .80 | .85 | .82 | .75 | .76 |

| Standsout | .74 | .82 | .82 | .83 | .82 | .84 | .79 |

| Uniqueness | .72 | .68 | .74 | .81 | .71 | .81 | .73 |

| Iconic | |||||||

| Cultural sign | .51 | .71 | .69 | .78 | .65 | .72 | .64 |

| Valued | .78 | .75 | .75 | .79 | .79 | .74 | .74 |

| Structural Coefficients (Betas) | |||||||

| Good looking | .62 | .68 | .71 | .76 | .72 | .68 | .72 |

| Original | .71 | .72 | .68 | .77 | .67 | .72 | .81 |

| High class | .79 | .82 | .72 | .87 | .78 | .82 | .78 |

| Popular | .75 | .71 | .81 | .86 | .81 | .71 | .76 |

| Subcultural | .89 | .88 | .86 | .89 | .86 | .85 | .88 |

| Iconic | .78 | .81 | .78 | .78 | .82 | .78 | .82 |

| Model Fit Statistics | |||||||

| Chi-square(d.f) | 1,885.1 (1,012) | 2,362.62 (1,004) | 2232 (1,.122) | 1,114.19 (512) | |||

| NNFI | .87 | .87 | .85 | .84 | |||

| CFI | .86 | .86 | .85 | .85 | |||

| RMSEA. | .052 | .062 | .069 | .076 | |||

| SRMR | .061 | .043 | .12 | .11 | |||

Tests of standard errors of high brand value with desire for the brand for high and low-value was 0.62(0.07) and 0.44(0.09). The correlation among value of the brand and how the respondents feel about the brand are 0.62 (0.06) and 0.55(0.07). The correlation among brand value and feeling about the brand are 1.2(0.59(0.7)) and 0.42(0.09). Among the brand dimensions and brand value every observation of correlation was below 1.2.

Outcomes and Mediation

The set of characteristics associated with a brand which explains its functions consists of multiple dimensions according to Aaker (1997). These characteristics have a definite effect on brand and how they are perceived is the exact way the brand value is perceived. The cross-sectional survey data makes it difficult to find out which was first and the effect on each other. The yielding model estimates of the effects of brand value on mediating and dependent variables (feeling, what they speak and pay) which are controlled and more conservative.

The outcomes of brand value, the nomological model noted the effects of brand value on all dependent variables to buy a brand. The high-value of brand is likable for consumers (Dar-Nimrod, 2012) which has more than one element which can be called likable. The brand value should be able to forecast feeling towards the brand. The high-value brand should be able to increase the desirability and liking towards the brand along with other factors which results in overall satisfaction (Oliver, 1980).

Delight is increased by the brand value of the product in the minds of the customer and high brand value is achieved by the good looks and the popularity of the brand. The value of the product is also expressed by the brand value which comprises of good looks, high status, iconic, popular, original and sub cultural (Berger & Heath, 2007).

How well the youth is in sync with the brand gives an idea of brand value (Escalas & Bettman, 2003) as youth are affected by peer pressure as being in sync increases brand value. The relationship between the brand and the customer is beyond just being in sync with the brand as youth see defining their identity with brand shows increased brand value (Batra, Ahuvia & Bagozzi, 2012). As the high-value brand seem to be desirable by all and leads to pride of ownership they are high-value brands (Tracy & Robbins, 2007).

The feeling of being in sync and pride of ownership results in willingness to pay a premium and spreading good things about the brand (Batra, Ahuvia & Bagozzi, 2012). These brands also have high status and are considered popular and iconic which help them sell more than the brands which are not of high-value as shows in Table 4.

| Table 4 Standard Deviations |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 5 | Study 6 | Study 7 | Study 8 (Fashion) | ||||||

| Brand value | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High unpopular | High popular | Low |

| n¼750 | n¼750 | n¼750 | n¼750 | n¼750 | n¼750 | n¼150 | n¼150 | n¼150 | |

| Good looking | 3.54(.48) | 2.82(.82) | 5.54(.91) | 3.74(1.02) | 3.42(1.07) | 5.28(.71) | 4.46(1.02) | 1.86(1.08) | 1.04(1.02) |

| Original | 3.52(.45) | 2.75(.77) | 5.44(.90) | 3.84(1.03) | 4.72(.79) | 3.24(.96) | 4.41 (.87) | 3.52(1.12) | 1.64(1.12) |

| High class | 3.06 (.92) | 2.01 (.89) | 4.61(1.09) | 3.24 (1.12) | 3.52 (.76) | 1.92 (1.02) | 2.88 (.98) | 2.91 (1.14) | 1.02 (1.02) |

| Popular | 3.59 (.42) | 2.91 (.79) | 5.42 (.85) | 4.23 (1.22) | 4.86 (.87) | 3.36 (.98) | 3.29 (.73) | 4.97 (.56) | 2.43 (1.32) |

| Subcultural | 2.54 (.89) | 2.05 (.87) | 4.56 (1.05) | 3.19 (1.09) | 3.54 (.58) | 1.92 (1.02) | 3.68(1.12) | 2.82 (1.18) | 1.31 (1.43) |

| Iconic | 3.02 (.78) | 2.45 (.98) | 4.72 (1.12) | 3.72 (1.22) | 4.63 (.43) | 2.85 (1.08) | 2.45(1.12) | 4.73 (.84) | 2.12 (1.42) |

| Manipulation checks | |||||||||

| High-value | 4.96 (.68) | 2.42 (1.48) | 4.12 (.64) | 1.12 (1.25) | 4.94 (.88) | 3.33 (1.02) | 1.43 (1.13) | ||

| High-value & popular | 4.42(1.46) | 1.21 (1.17)c | 2.94 (.92) | 3.71 (.71) | 1.59 (1.14) | ||||

| Brand value before | .27(.61) | .12(.76) | -.28(.46) | ||||||

| Brand value in future | .27(54) | -.11(.62) | -.28(.51) | ||||||

| Outcome variables | |||||||||

| Brand attitudes | 3.24 (.41) | 2.21 (.94) | 2.24 (.52) | 1.21(1.31) | 2.02(1.02) | 2.36(1.02) | .94(.89) | ||

| Relationship with the brand | 1.6 (.72) | 1.22 (.82) | 1.41 (.72) | 1.22(1.23) | 2.54(.82) | 2.14(.87) | 2.12(.31) | 1.65(.48) | 1.2(.51) |

| Willingness to Say | 2.12 (.96) | 1.54 (.85) | 2.21 (.81) | 1.21 (.80) | 2.98 (1.62) | 1.61 (.88) | 2.92 (1.22) | 3.12(1.12) | 1.21(1.24) |

| What they said | 1.42 (.94) | 1.15 (.86) | 1.92 (.82) | 2.46 (.82) | 1.02 (.92) | ||||

| Willingness to pay | 1.17 (.67) | 1.67 (.86) | 2.78 (.82) | 1.81 (.92) | 3.18 (.98) | 2.27 (1.29) | 3.12 (.93) | 2.92 (1.03) | 1.14 (1.01) |

| High price | 2.45 (.78) | 2.21 (.92) | 2.28 (.68) | 3.62 (.52) | 1.81 (.89) | ||||

| Popular | 2.85 (.49) | 2.43 (.58) | 1.46 (.71) | 2.91 (.49) | 2.83 (.73) | ||||

| Brand Personality | |||||||||

| Stylish | 3.14 (1.04) | 2.58 (1.09) | 2.88 (.93) | 2.11 (.93) | |||||

| Durable | 3.53 (1.07) | 2.92 (1.15) | 3.28 (1.05) | 2.57 (1.13) | |||||

| Efficient | 4.34 (.71) | 3.54 (.98) | 4.06 (.78) | 3.38 (1.10) | |||||

| Interesting | 4.05 (.80) | 3.21 (1.06) | 3.75 (.88) | 2.65 (1.01) | |||||

Outcomes of Nomo Logical Models

The calculations were assessed modelling high-value of brands with the dimensions of personalities leading to a group of values such as being in sync with the brand, willingness to pay and say etc. The sample size to the number of parameters that are estimated as per the predictive model (Bagozzi & Edwards, 1998) the mean for each predicted variable was noted. A structural equation model was created were value of the brand as an independent variable and the results like being in sync and willingness to pay were taken as dependent ones. The dimensions of brand personality were the correlates used. The model fit did well across all tests. Brand value was correlated will the various dimensions of brand personality. Being high class and efficient were the most related to high-value of the brand. The high brand value indicates the measure consequence variables in all the studies.

High Brand Value by Variance

Whether customers are having a positive attitude towards the brand which can help marketers with new knowledge we test the amount of variance of high brand value shown in the resulting variables comparative to constructs like sync with the brand and spreading word of mouth. In all the tests conducted, the high-value of the brand of the variance in attitude of the brand, which is same as the variation shown by brand sync and willingness to pay. High brand value explained a comparable level of variance across all aspects. The outcomes prove that brand value is too deep to and can be considered a construct itself. The mean levels increase when the value of the brand is high. The mean level of brand on the results is high in case of the brand value being high

Mediation

The nomological models show the effects of brand value on result variables which were not assessed on mediation. The data obtained from cross-section doesn’t show causal orders but when tested for consistency with the hypothesis that being in sync with brand and willingness to pay mediate the effects of the high-value brand on the attitude towards the brand, its value and what is said about it. The structural equation model is used to test the mediating paths that are used as hypothesis. The impact of high-value brand on every one of the dependent variables was fully mediated by belongings to the brand i.e is being in sync with the brand and willing ness to pay and say about the brand. In the test 7 that was conducted high-value of the brand impacted the brand attitude and belongings. The belongingness impacted the attitude towards the brand and the willingness to pay and say and the belongingness impacted the attitude about the brand. The high-value brand also effected the attitude towards the brand and the willingness to pay but did not affect what customers said about the brand to others. Belongingness about the brand mediates the impact of brand value on what customers say about the brand but did not impact on attitude towards the brand and their willingness to pay. This shows that high-value of the brand is because of their belongingness and being in sync with the brand which are customer’s reaction to a brand based on how they perceive the brand. The test 7 show large variations in in the constructs by higher order brand values and the mediation pathways of these effects.

As shown the tables for all the test results, it proved that effects of high brand value on dependent variables like attitude, willingness to talk about the brand and pay were mediated by belongingness towards the brand and customers being in sync with the brand.

Factor Method Test

We examined the how common method bias impacts structural models by marker variables technique given by Williams, Hartman & Cavazotte (2010). The marker variables were based on experience and expectation of quality of brands to the constructs of research interest in research. Marker variable method towards the study for method bias did not show glitches in these tests.

How Brands Change Over Time

Brand values don’t stay same. They are created in some outside countries and subcultures and move towards becoming a high-value brand (Belk, Tian & Paavola, 2010). How nature of brands gets effected as they move and how customers respond over the journey of the brand.

This was answered in the test 8 were respondents were shown brands that they thought were of high-value but had not become popular yet and those that have become popular. Three test were conducted on High-value brands that were not popular, high-value brands that were popular and low-value brands. The first one being comparing the low-value brands with the high-value brands that were popular and high-value brands that were not popular. Next test was conducted between high-value brands that were popular and high-value brands that were not popular.

Test Rechecks

Low-value brands were perceived to be of low-value than high-value brands by participant by themselves and what they thought their peers perceived it as. But the correlation between value of the brand as they thought their peers perceived it was low. High-value brands that were popular and high-value brands that were not popular also were different. High-value brands that were not popular were considered highly valued by the respondents themselves but not so highly valued by others. The journey of the brand was forecast differently also. Respondents expected the brands not so popular to become popular in the future compared with the high-value brand that is already popular and low-value brand. Respondents said that low-value brands will further lose their value in the long run and expected the popular brands to have the same consistent brand value.

How a High-value Brand is Dissimilar from a Low-value Brand?

All the elements among high brand value had been perceived at a higher order. The status, popularity etc were was more favourable for the high brand valued product than the low valued one. The elements about brands do undergo changes in the future but there were certain changes that were perceived by the respondents among high and low valued brands. Within high-value brands, the not yet popular category brands were seen as more subcultural, good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic. When the high brand value moves from unpopular to popular category, the elements undergo certain changes during this time. The popular high-value brands were spoken about more as the respondents were exposed these brands more than the brands that were high-value but not popular in the Inkjet. They were willing to pay more for the popular brands and preferred to buy them over the not so popular high-value brands. But the not so well known brands were considered to more in sync with the respondent’s personality which also made them willing to pay more to high-value brand which may not be so popular. The changing course of elements is shown inn Table 2.

Elements of a High-value Brand

The elements of low-value brand are not like the high-value brands. We need to examine if we change the value of the elements will the brand value be perceived differently by the respondents. The fashion brands were selected as a sample and their elements were influenced and changed to check if the brand values also change in the minds of the customer. For the study, only high and low-value brands were selected. Respondents were asked perceive brands they were exposed after showing them the print ads of fashion brands. Since they were already exposed to these brands before, our tests observed whether elements of the brands change the perceptions of the brand value. The brand would generally have a high brand value when the respondents were said it had more of the six elements under study. For example, respondents were shown a fashion brand and said it was used by high-status people.

Experiment Methodology

Respondents in the age group of 18-23 were selected from a cosmopolitan university Manipal University, which is the number 1 private university in India. All the respondents were to read about a brand from Norway which does not exist in India and were divided to any of the two categories of high and low among the six elements under study. Respondents were then shown the reviews written the customers of the brand online. Only those reviews which spoke about the six elements either high or low were selected for the experiment for the purpose of our study. All the sentences were exposed for 10 seconds and all the sentences were selected within the prescribed category randomly. Respondents went through a series of measures. The personal details of respondents were not asked for during the experiment.

Outcomes

Brand value was tested after the six elements were modified according the experiments. The outcomes showed the impact of all these six elements on the brand value. The brand was a high-value brand when it was seen as Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. The brands that were seen less on these above six elements were low-value brands.

Effects of Perceptions of the Respondents

The next experiment was to see if six elements effected the willingness to pay and say about the brand. Structural equation modelling was used for measuring the impacts. The complete and partial mediation showed a high chi-square difference proving that the model with one or more direct paths was the model with the best fit. ANOVA results proved that all six elements increased the brand value significantly. This value of the brand increased the attitude, willingness to pay and speak about the brand. So, the effect of these six elements was on dependent variables was not mediated by brand value in every experiment done. Dependent variables in some cases were also affected by the manipulation of these elements but due to limitations of our study we cannot study these results.

Effects

The results show that the six elements decide of a brand value is perceived by the customers. This brand value decides the buyer attitude, the willingness to pay for the brand and what the prospective customers speak about the brand. So, this brand value causes a chain reaction which overall decides how high or low the brand value becomes in the future. The future research could focus on more characteristics that will influence the brand value.

Discussions

Experiments prove that the brand value is an integrative effect of Good looking, high class, original, popular, iconic and sub cultural. Top brands like Lexus is considered high-value because its good looking, high class and popular. Coca-cola is seen as iconic and original. These six elements in Indian market distinguish high and low-value brands. These elements vary but are closely knit together forming a higher-order structural model of brand value.

The Brand Journey

The research add to the existing knowledge about brands and brand value (Paramentiar & Fischer 2014) by identifying how these elements change as the brand moves on scale of the popularity. Brands are usually accepted in western countries before they come to Indian and Asian markets (Ulla & Hawaldar, 2019). Not all brands are capable to become popular across western and Asian markets as some fail to be accepted inspite of being popular in the European countries. Levis was initially accepted by youth but now has spread to the entire demography of India, so is Woodlands footwear. These brands in course of their journey however decline in their uniquness towards the innovators. But in the course of the journey the brands should not move away its charecteristics or youth will soon shun these brands and will no longer assosiate these six elements with them

Mangerial Implications

The success of a brand depends solely in its value and managers have tried to figure this out always (Anik, Miles & Hauser, 2017). How to increase the brand has never been measured which has always made magerial decision making difficult in the Indian marketing environment. The article provides the roadmap to managers as to how to build a high-value brand in India. The structural model finds out the charectristics of the brand that give high-value, which are the charectristics that are important in brand building and how they change over time and the journey of the brand. This article can mainly used for marketing programs of various brands to position itself as a high-value brand. If the value of a marketers brand is low, the marketing need to reposition their brands on these charecteristics. These brands to build a value must be good looking as shown in our findings, the design teams need to develop products that are beautiful to look at as Indians look for aesthetics more than anything else. The marketers need to make sure that high-class customers use their products in public which will position their brands above others as Indians attach a lot of respect towards people who become successful in life. Customers should always see an original product as cheap imitations can never be regarded as high class by Indians. No amount of advertisements can make an imitation look high-value in the minds of the Indians. Marketers need to have a popular opinion about the product without over advertising. The firms should also focus on hiring brand ambassadors and creating a history for the brand like lux which make the brand look iconic. The companies like Royal Enfield bullet looks more sub cultural because of the way the brand is linked to its user base. Brand must identify if they are high-value unpopular, high-value popular or low-value brands. If marketer of a low-value brand wants to make it popular, first he should make it high-value to small group of Indian customers and then move the brand to be accepted by larger customers. For this, the marketers need to focus on innovators will take the risk of trying a brand for the first time. During the journey from unpopular to highly popular the connection with the charecteristics with which the brand started must still be maintained.

Future Research

Future research could be conducted on how how brand value connected to these charesteristics to what extent can be studied. The meadiation analysis measured variables butnot every sequence. Cross lagged analysis of time series data to test causal sequences can be done. Future researchers can work on analysing common methods bais. The data was collected from youngsters coming from variouscultures but we have not analysed cross-cultural diffrences. Future research need to focus on how customers react to high-value brands and how cultural diffrences moderate the customers perceptions. How these charecteristics are related among themseleves can be researched by the researchers. Further researches can identify how brand value effects the success of the brand.

References

- Aaker, J.L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of marketing research, 34(3), 347-356.

- Anik, L., Miles, J., & Hauser, R. (2017). A general theory of coolness.

- Bagozzi, R.P., (2007). On the meaning of formative measurement and how it differs from reflective measurement.

- Bagozzi, R.P., (2011). Measurement and meaning in information systems and organizational research. Methodological and philosophical foundations, 261-292.

- Bagozzi, R.P., & Edwards, J.R. (1998). A general approach for representing constructs in organizational research. 1(1), 45-87.

- Bagozzi, R.P., & Heatherton, T.F. (1994). A general approach to representing multifaceted personality constructs. A Multidisciplinary Journal, 1(1), 35-67.

- Bagozzi, R.P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 40(1), 8-34.

- Bartl, C., Gouthier, M.H. & Lenker, M. (2013). Delighting consumers click by click: Antecedents and effects of delight online. Journal of Service Research, 16(3), 386-399.

- Batra, R., Ahuvia, A., & Bagozzi, R.P., (2012). Brand love. Journal of marketing, 76(2), 1-16.

- Bearden, W.O., Netemeyer, R.G. & Teel, J.E., (1989). Measurement of consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. Journal of consumer research, 15(4), 473-481.

- Becker, M., Wiegand, N., & Reinartz, W.J., (2019). Does it pay to be real? Understanding authenticity in TV advertising. Journal of Marketing, 83(1), 24-50.

- Belk, R.W., Tian, K. & Paavola, H., (2010). Consuming cool: Behind the unemotional mask. Research in consumer behavior, 12(1), 183-208.

- Berger, J., & Heath, C. (2007). Where consumers diverge from others: Identity signaling and product domains. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 121-134.

- Beverland, M.B., Lindgreen, A. & Vink, M.W. (2008). Projecting authenticity through advertising: Consumer judgments of advertisers' claims. Journal of Advertising, 37(1), 5-15.

- Bird, S., & Tapp, A. (2008). Social marketing and the meaning of cool. Social Marketing Quarterly, 14(1), 18-29.

- Bruun, A., Raptis, D., Kjeldskov, J., & Skov, M.B., (2016). Measuring the coolness of interactive products: the COOL questionnaire. Behaviour & Information Technology, 35(3), 233-249.

- Connor, M.K. (1995). What is cool? Understanding black manhood in America. Crown Publishers, Inc.

- Danesi, M. (1994). Cool: The signs and meanings of adolescence. University of Toronto Press.

- Dar-Nimrod, I., Hansen, I.G., Proulx, T., Lehman, D.R., Chapman, B.P., & Duberstein, P.R. (2012). Coolness: An empirical investigation. Journal of Individual Differences.

- Dar-Nimrod, I., Ganesan, A., & MacCann, C., (2018). Coolness as a trait and its relations to the big five, self-esteem, social desirability, and action orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 121, 1-6.

- Diamantopoulos, A., Riefler, P., & Roth, K.P. (2008). Advancing formative measurement models. Journal of business research, 61(12), 1203-1218.

- Edwards, J.R. (2011). The fallacy of formative measurement. Organizational Research Methods, 14(2), 370-388.

- Escalas, J.E., & Bettman, J.R. (2003). You are what they eat: The influence of reference groups on consumers’ connections to brands. Journal of consumer psychology, 13(3), 339-348.

- Finn, A. (2005). Reassessing the foundations of customer delight. Journal of Service Research, 8(2), 103-116.

- Fiske, S.T., Cuddy, A.J., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in cognitive sciences, 11(2), 77-83.

- Fitton, D., Horton, M., Read, J.C., Little, L., & Toth, N. (2012). Climbing the cool wall: Exploring teenage preferences of cool. In CHI'12 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems, 2093-2098.

- Frank, T. (1997). The conquest of cool: Business culture. Counterculture, and the rise of hip.

- Friese, S. (2011). Using ATLAS. TI for analyzing the financial crisis data. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1).

- Gerzema, J., Lebar, E., & Rivers, A. (2009). Measuring the contributions of brand to shareholder value (and how to maintain or increase them). Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 21(4), 79-88.

- Gladwell, M. (1997). The coolhunt: Who decides what’s cool? Certain kids in certain places–and only the coolhunters know who they are. The New Yorker, 17.

- Geuens, M., Weijters, B., & De Wulf, K. (2009). A new measure of brand personality. International journal of research in marketing, 26(2), 97-107.

- Gurrieri, L. (2009). Cool brands: A discursive identity approach. In ANZMAC 2009: Sustainable Management and Marketing Conference Proceedings.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., & Tatham, R.L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis, 6.

- Hawaldar, I.T., Ullal, M.S., Birau, F.R., & Spulbar, C.M. (2019). Trapping fake discounts as drivers of real revenues and their impact on consumer’s behavior in india: A case study. Sustainability, 11(17), 4637.

- Heath, J., & Potter, A., (2004). Nation of rebels: Why counterculture became consumer culture. Harper Collins.

- Hebdige, D. (2012). Subculture: The meaning of style. Routledge.

- Holt, D.B. (1998). Does cultural capital structure American consumption? Journal of consumer research, 25(1), 1-25.

- Holt, D.B., & Holt, D.B. (2004). How brands become icons: The principles of cultural branding. Harvard Business Press.

- Holt, D., & Cameron, D. (2010). Cultural strategy: Using innovative ideologies to build breakthrough brands.

- Horton, M., Read, J.C., Fitton, D., Little, L., & Toth, N. (2012). Too cool at school-understanding cool teenagers. PsychNology Journal, 10(2), 73-91.

- Howell, R.D., Breivik, E., & Wilcox, J.B. (2007). Reconsidering formative measurement. Psychological methods, 12(2), 205.

- Hurt, H.T., Joseph, K., & Cook, C.D. (1977). Scales for the measurement of innovativeness. Human Communication Research, 4(1), 58-65.

- Im, S., Bhat, S., & Lee, Y. (2015). Consumer perceptions of product creativity, coolness, value and attitude. Journal of Business Research, 68(1), 166-172.

- Keller, K.L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of marketing, 57(1), 1-22.

- Kerner, N., & Gene, P. (2007). Chasing cool: Standing out in today's cluttered marketplace. Simon and Schuster.

- Levy, S.J. (1959). Symbols for sale. Harvard business review.

- Mailer, N., Malaquais, J., & Polsky, N. (1957). The white negro San Francisco: City Lights Books. 4.

- Martin, P.Y., & Turner, B.A. (1986). Grounded theory and organizational research. The journal of applied behavioral science, 22(2), 141-157.

- McCracken, G. (1988). The long interview. Sage.

- Milner, M. ( 2013). Freaks, geeks, and cool kids. Routledge.

- Mohiuddin, K.G.B., Gordon, R., Magee, C., & Lee, J.K. (2016). A conceptual framework of cool for social marketing. Journal of Social Marketing.

- Morhart, F., Malär, L., Guèvremont, A., Girardin, F., & Grohmann, B. (2015). Brand authenticity: An integrative framework and measurement scale. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(2), 200-218.

- Nancarrow, C., Nancarrow, P., & Page, J. (2002). An analysis of the concept of cool and its marketing implications. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, 1(4), 311-322.

- Napoli, J., Dickinson, S.J., Beverland, M.B., & Farrelly, F. (2014). Measuring consumer-based brand authenticity. Journal of Business Research, 67(6), 1090-1098.

- Netemeyer, R.G., Krishnan, B., Pullig, C., Wang, G., Yagci, M., Dean, D., … & Wirth, F. (2004). Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of business research, 57(2), 209-224.

- Newman, G.E., & Smith, R.K. (2016). Kinds of authenticity. Philosophy Compass, 11(10), 609-618.

- Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric theory: (2nd edition). McGraw-Hill.

- O’Donnell, K.A., & Wardlow, D.L. (2000). A theory on the origins of coolness. ACR North American Advances.

- Oliver, R.L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of marketing research, 17(4), 460-469.

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H.M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological bulletin, 128(1), 3.

- Parmentier, M.A., & Fischer, E. (2015). Things fall apart: The dynamics of brand audience dissipation. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(5), 1228-1251.

- Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., & Podsakoff, N.P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), 879.

- Pountain, D., & Robins, D. (2000). Cool rules: Anatomy of an attitude. Reaktion books.

- Read, J., Fitton, D., Cowan, B., Beale, R., Guo, Y., & Horton, M. (2011). Understanding and designing cool technologies for teenagers. In CHI'11 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1567-1572.

- Rodkin, P.C., Farmer, T.W., Pearl, R., & Acker, R.V. (2006). They’re cool: Social status and peer group supports for aggressive boys and girls. Social Development, 15(2), 175-204.

- Runyan, R.C., Noh, M., & Mosier, J. (2013). What is cool? Operationalizing the construct in an apparel context. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal.

- Ruvio, A., Shoham, A., & Bren?i?, M.M. (2008). Consumers' need for uniqueness: Short?form scale development and cross?cultural validation. International Marketing Review.

- Schouten, J.W., & McAlexander, J.H. (1995). Subcultures of consumption: An ethnography of the new bikers. Journal of consumer research, 22(1), 43-61.

- Southgate, N., (2003). Coolhunting, account planning and the ancient cool of Aristotle. Marketing Intelligence & Planning.

- Sriramachandramurthy, R., & Hodis, M. (2010). Why is apple cool? An examination of brand coolness and its marketing consequences. American Marketing Association. 147-148.

- Sundar, S.S., Tamul, D.J., & Wu, M. (2014). Capturing “cool”: Measures for assessing coolness of technological products. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 72(2), 169-180.

- Thornton, S., (1995). Club cultures: Music, media and subcultural capital. Cambridge: Polity.

- Tian, K.T., Bearden, W.O., & Hunter, G.L. (2001). Consumers' need for uniqueness: Scale development and validation. Journal of consumer research, 28(1), 50-66.

- Tracy, J.L., & Robins, R.W. (2007). The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets. Journal of personality and social psychology, 92(3), 506.

- Ullal, M.S., & Hawaldar, I.T. (2018). Influence of advertisement on customers based on AIDA model. Problems and Prospective in Management, 16(4), 285-298.

- Warren, C., Batra, R., Loureiro, S.M.C., & Bagozzi, R.P. (2019). Brand coolness. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 36-56.

- Warren, C., & Campbell, M.C. (2014). What makes things cool? How autonomy influences perceived coolness. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(2), 543-563.

- Warren, C., Pezzuti, T., & Koley, S. (2018). Is being emotionally inexpressive cool? Journal of Consumer Psychology, 28(4), 560-577.

- Warren, C., & Reimann, M. (2019). Crazy-funny-cool theory: Divergent reactions to unusual product designs. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 4(4), 409-421.

- Williams, L.J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational research methods, 13(3), 477-514.