Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 4S

Impact of cultural intelligence on strategic excellence, for virtual teams

Amani Abu Rumman, Al-Ahliyya Amman University

Citation Information: Rumman, A. (2022). Impact of cultural intelligence on strategic excellence, for virtual teams. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(S4), 1-8.

Abstract

In today's world, in which technologies of distance communication are improving, and boundaries are increasingly blurred, business owners and managers need to be able to effectively interact with representatives of other cultures. Globalization and the ability to work remotely make it possible to collaborate with experts and employees from different countries. A remote team is a job, provided that the company does not have a physical office at all. All employees have the opportunity to work from anywhere in the world by simply connecting to the Internet and using a specific set of virtual instruments. This particular study has utilized the cultural intelligence questionnaire to study the metacognitive, cognitive, motivational and behavioral factors of influence with their respective correlation to the satisfaction rate and excellence of virtual teams in Jordan Telecom. The p-value factor is smaller than the anchor point of 0.05 for all factors demonstrating their importance in the establishment and functioning of virtual teams.

Keywords

Cultural Intelligence, Strategic Excellence, Virtual Teams, Orange Jordan Telecom

Introduction

Representatives of different cultures participate not only in business negotiations at different levels, but also in business conversations, conferences, forums, and high-level meetings leading to strategic excellence of the individual and overall success. Communication between representatives of different cultures takes place in the process of intercultural communication in compliance with the norms of etiquette and the characteristics of those cultures and traditions that are inherent in the communicants. In order to effectively maintain a variety of intercultural contacts and forms of communication, partners need not only knowledge of the relevant language, but also knowledge of norms, rules, traditions, customs, etc. another culture. The proper and direct way of understanding intercultural communication requires knowledge of a whole set of rules and standards of behavior, including those pertaining to the communication of the partner. We believe that knowledge and study of the influence of cultural intelligence on intercultural communication is an important link that is necessary for representatives of different companies in business negotiations, since the ability to navigate in a situation with partners representing a different culture affects both the process itself and the effective result. Cultural intelligence, as defined by Brooks Peterson (2018), is the ability to use a set of behaviors that rely on qualifications (e.g. language or communication) or qualities (e.g. tolerance for uncertainty, flexibility) appropriately attuned to cultural values and beliefs (Peterson, 2018). Other researchers see cultural intelligence as the innate ability to proper interpersonal interaction with an individual of another country. It is never possible to be fully prepared thus one must understand the surrounding and the signals coming from the other party thereby warning of improper behavior towards their elder.

The purpose of our study is to analyze the features of cultural intelligence, its influence on the negotiation process and on intercultural communication thereby determining strategic excellence of team performance, by which we mean communication of people representing different cultures (Peterson, 2018). In addition, to present the possibilities of defining cultural intelligence.

Thesis: A high level of cultural intelligence is an important factor in determining the overall success of strategic excellence of the team in particular and company in general.

Literature Review

Considering the term "cultural intelligence", it should be noted that it denotes both "skill" and "ability". Since in modern studies, like (Flaherty, 2015) for example, it is shown that cultural intelligence is the ability to effectively interact with carriers of different cultures, which requires a person to have certain skills in order to interpret unfamiliar and ambiguous gestures in such a way as it would be done by a bearer of culture.

Thomas, et al., (2015) also considers cultural intelligence, referring to Gardner who believes that cultural intelligence has four components of it: linguistic intelligence, spatial intelligence, interpersonal intelligence and intra-personal intelligence, which are included in the seven types of the theory of multiple intelligences and described in Gardner’s book Intelligence Reframed (1999). Linguistic intelligence, in his opinion, is "the ability to quickly process linguistic messages. It consists of semantics, phonology, syntax, and pragmatics. Thomas, et al., (2015) consider spatial intelligence to be the ability to find a way in difficult conditions, engage in various types of arts and crafts and play various games, appreciate numerous sports (Livermore, 2009). Gardner believed that this kind of intelligence is inherent in all cultures. The scholar combined interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences and called them "personal intelligences" because they represent the ability to process two types of information (Livermore, 2009). The first is our ability to recognize other people - to distinguish between their faces, voices and personalities (Gardner, 1999). The second type of information is sensitivity to our own feelings, desires and fears, personal experiences (Gardner, 1999).

Considering the four types of components of cultural intelligence in the context of their application for interaction in intercultural communication, it should be noted that linguistic intelligence will be successfully used in communication with representatives of other cultures when you know the language of the local population and use it in negotiations or in other communication situations (Thomas & Inkson, 2017). Spatial intelligence manifests itself as an important component of cultural intelligence when interacting with carriers of other cultures when you need to know how to behave at the table, how to behave correctly during a meeting, a business meeting and in other communication situations, so as not to find yourself in an absurd situation (Thomas & Inkson, 2017). Spatial intelligence is used to explain simple things, such as how close you can stand to each other during a conversation, where the most important person should sit at the table, how to arrange chairs, whether to bow, shake hands or touch each other, and the ability to understand, predict and sometimes mimic body language correctly (Thomas & Inkson, 2017). Of the four components of cultural intelligence identified by Gardner, the most uncertain are the risks of intrapersonal intelligence, which are associated with different cultural styles (Livermore, 2009). If a person knows his cultural style, then it will be easier for him to compare himself with others and then adjust his behavior to make it compatible with the intercultural environment in which he communicates or where negotiations are taking place (Thomas & Inkson, 2017). Gardner describes interpersonal intelligence as the ability to "read the intentions and desires of other people, even if they are hidden" (Gardner, 1999). Reading and anticipating desires and motivation is a critical aspect of interpersonal intelligence for international business professionals (Thomas & Inkson, 2017). This skill is especially developed by doctors, teachers and politicians, as well as by an international sales representative who foresees what will affect the conclusion of a deal when negotiating with representatives of other cultures (Thomas & Inkson, 2017). Cultural intelligence researcher Brooks Peterson argues that “for successful relationships with representatives of other cultures, you can help: (a) the ability to speak a little in their language: (b) knowledge of distance (and other types of non-verbal behavior); (c) knowledge of one's own cultural style, and; (d) knowing how compatible your cultural style is with others" (Peterson, 2018).

Since we are considering the features of cultural intelligence from the point of view of business negotiations, it is necessary to take into account emotional intelligence, which is an integral part of cultural intelligence. Emotional intelligence is considered to be primarily based on such characteristic traits as self-motivation, emotional control, mood regulation, empathy and the ability to maintain one’s hopes alive. For our study, the definition of scientists Caligiuri & Tarique (2009) is more suitable, who believe that emotional intelligence is the ability to understand the meaning of emotions and use this knowledge to find out the causes of problems and solve these problems (Caligiuri & Tarique, 2009). Al-Zoubil & Al-Adawi (2019) suggested that emotional intelligence determines the presence of various abilities that are involved in the adaptive processing of emotional information.

The exchange of information occurs not only during communication in different situations, but also during negotiations. And here the influence of personal intelligences manifests itself, which, according to Gardner (1999), have the ability to "process two types of information", of which one is associated with the recognition of faces, voices, and the other information is associated with sensitivity, personal experiences, and therefore more emotional (Al-Zoubil & Al-Adawi, 2019).

When exchanging information, by which we mean the exchange of information in society and in nature in its various forms ... messages informing about the state of affairs, about the state of something, the same information will not only be transmitted in different ways, but also perceived by different peoples in different ways, depending on traditions, cultural values and customs, as well as on their cultural intelligence (Boyatzi et al., 2000; Cote & iners, 2006). The exchange of information during negotiations between business people will be completely different than the exchange of information between friends or students, regardless of the country in which it occurs. Intercultural communication, by which we mean the process of communication and interaction between various interlocutors with a different cultural background. At the same time this is the process of interaction itself communicants who are carriers of different cultures and languages. Here, each message reflects the specifics of the national culture and features of intercultural communication of any country (Crowne, 2008). Thus, for example, representatives of low contextual cultures will be more interested in detailed information of the message, since in these cultures the of utmost importance is the process of speech alongside the specific details that one shares with another interlocutor in the process of communication in a direct manner (Fee et al., 2013; Yusof et al., 2014). Representatives of these cultures during negotiations will be distinguished by expressiveness of speech and a clear and clear assessment of all discussed topics and issues raised during the transfer of information.

Representatives of highly contextual cultures are more sociable and emotional, because they use a dense information network, involving close contacts between family members, constant contacts with friends, colleagues, clients and will perceive messages in a restrained and concise manner, without asking details. Scholars argue the level of emotionality depends on belonging to a particular culture (Gregory et al., 2009). For example, Americans tend to use short phrases a lot, and in many highly contextual (Eastern) cultures this form of communication is frowned upon. Moderation and restraint are cultivated in low contextual cultures (Hampden-Turner & Trompenaars, 2006).

Considering the influence of cultural intelligence on the negotiation process, it should be noted that, depending on which culture representatives are negotiating with, the participants will know which words at which point in the negotiations should be used correctly (Ward et al., 2010). For example, to set the tone and propose a suitable key to the negotiation process, Leach's postulates of politeness are useful, which are used by negotiators at certain stages: typical for the final stage of negotiations - summing up and concluding a deal (Huang et al., 2012). The postulates of politeness are used at the level of interpersonal rhetoric, providing also social balance and good relations between people, which is a necessary platform for cooperation (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013).

Spatial intelligence is manifested in communicants not only during negotiations, but also during a preliminary conversation, when it is necessary to maintain a distance during communication, to correctly arrange chairs in a negotiating room in accordance with the etiquette of the culture where negotiations are taking place (MacNab & Worthley, 2012). Here knowledge and skills related to cultural intelligence are manifested, since the negotiators must be trained in advance in those cultural nuances that will be taken into account and will not interfere with the negotiation process, but, on the contrary, will contribute to a positive result of the negotiations (Jordan et al., 2002; Jackson, 2013).

The intensification of intercultural interaction associated with the strengthening of global processes in the world has given rise to the need for a deeper understanding of the abilities that ensure success in a multicultural space. In response to this request, at the junction of modern theories of intelligence and psychological approaches to understanding the features of intercultural interaction, the concept of cultural intelligence was born (Pashler et al., 2016). Cultural intelligence can be defined as a type of social intelligence aimed at a specific social context determined by cultural characteristics. If social intelligence is aimed at solving problems, first of all, within the framework of one culture, then cultural intelligence ensures the success of an individual when interacting at the border of cultures. Cultural intelligence includes cognitive, metacognitive, motivational and behavioral components, covering the main levels of interpersonal interaction and providing an integrative approach to solving cross-cultural situations characterized by complexity, uncertainty, diversity of cultural dimensions, and adaptation to them (Pashler et al., 2016). It should be noted that the allocation of the metacognitive component of cultural intelligence favorably distinguishes this concept from other approaches that analyze the success of intercultural interaction only at the cognitive, motivational and behavioral levels. The effectiveness of this concept and the availability of methodological tools led to its widespread use in the framework of empirical research.

Analyzing "personal intelligences", which are associated with the need to know one's own cultural style, as well as knowledge and compatibility of other cultural styles in negotiation, it is necessary to consider communicative communication styles that are associated with culture and reality, since communication style is understood as a way of expressing a message, which indicates how the meaning of the message should be conveyed, interpreted and understood (Dyne et al., 2009; Vedadi et al., 2010; Pashler et al., 2016). Psychologists have identified 10 basic communication styles that represent the ways people interact in the process of communication, which depend on the cultural characteristics and individual communication experience of each participant in the communication (Perrinjaquet et al., 2007; Ramalu et al., 2010; Rockstuhl et al., 2011). One must consider these communication styles: 1. dominant style; 2. dramatic; 3. controversial; 4. soothing; 5. impressive; 6. accurate; 7. attentive; 8. inspired; 9. friendly; 10. open in which there is a tendency to express one's opinion, feelings, emotions. Research on communication styles in the United States and Japan has shown that there are significant cultural differences in eight out of ten communication styles (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013). For example, in the United States, attentive, controversial, dominant and impressive communication styles are more developed, while in Japan calming, dramatic and open communication styles are more pronounced. Consequently, in every culture there are several communication styles that either facilitate communication between partners or hinder it Tarique & Takeuchi, 2008). Therefore, knowledge of communication styles in different cultures contributes to the use in negotiations of the strategy that will be adequate to the negotiation style that will allow you to get an effective negotiation result and reach a consensus (Templer et al.,2006; Alqatanani, 2017).

Methodology

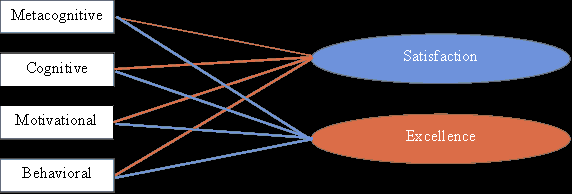

Having examined and analyzed cultural intelligence and its components, we came to the conclusion that every negotiator needs to master and apply cultural intelligence during business meetings and negotiations in all the variety of components. First of all, the negotiators themselves must assess their cultural intelligence through the Cultural Intelligence questionnaire offered by Brooks Peterson, which presents 22 human qualities that require improvement in order to speak about the presence of cultural intelligence. On the basis of this questionnaire, it is possible to conduct research on cultural intelligence according to the Cultural Intelligence Scale developed by a group of scientists, including Sung Ang and Lynn Van Dyne (Ang & Van Dyne, 2015), to solve research and applied problems related to cultural intelligence. The questionnaire was revised and developed into a multidimensional test in which four basic components of the proposed model are identified: metacognitive, which is responsible for the strategies in business operations; a cognitive component that indicates knowledge of the norms and etiquette of different countries and is associated with the cultural environment; the motivational component shows the ability to direct their energy to mastering and studying the culture of those countries with which their companies are negotiating; the behavioral component is expressed in the flexibility of the behavior of the verbal and non-verbal negotiator during negotiations and the ability to learn this flexibility in the future (Appendix A) (Ang & Van Dyne, 2015).

Participants

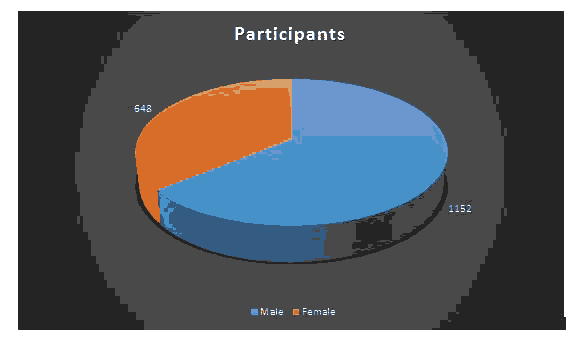

The participants were members of the Virtual Teams in Orange Jordan Telecom amounting to 1800 employees who all willingly participated in the study.

Method

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, all participants received a digital copy of the Cultural Intelligence Scale with a request to fill it in. The results were gathered and analyzed using IBM’s SPSS software package in an attempt to determine whether emotional intelligence can at all influence strategic excellence of the team.

Results

The descriptive statistics show that 64% were males (n=1152), whereas 36% were female (n=648) (Figure 1).

It seems strange that only 90% (n=1620) participants have demonstrated that they are happy with the situation at the company and that it helps them in achieving strategic excellence (Table 1).

| Table 1 Cultural Intellect and Strategic Excellence Situational Satisfaction at Orange Jordan |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 1620 | 900.0 | 900.0 | 900.0 |

| No | 180 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1000.0 | |

| Total | 1800 | 1000.0 | 1000.0 | ||

The four domains analyzed were metacognitive, cognitive, motivational, and behavioral. The response pertaining to these spheres were analyzed and correlated against the participants’ satisfaction rate and the deemed strategic excellence demonstrated by them at Orange Jordan. These results are presented in the table below:

| Table 2 Correlations of Designated Domains |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metacognitive | Cognitive | Motivational | Behavioral | Satisfaction | Excellence | ||

| Metacognitive | Pearson Correlation | 1 | -0.298** | 0.379** | 0.625** | -0.104** | -0.104** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | |

| Cognitive | Pearson Correlation | -,298** | 1 | -0.621** | -0.439** | -0.035 | -0.035 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.134 | 0.134 | ||

| N | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | |

| Motivational | Pearson Correlation | 0.379** | -0.621** | 1 | 0.429** | 0.095** | 0.095** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | |

| Behavioral | Pearson Correlation | 0.625** | -0.439** | 0.429** | 1 | -0.048* | -0.048* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.043 | 0.043 | ||

| N | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | |

| Satisfaction | Pearson Correlation | -0.104** | -0.035 | 0.095** | -0.048* | 1 | 10.000** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.034 | 0.001 | 0.043 | 0.001 | ||

| N | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | |

| Excellence | Pearson Correlation | -0.104** | -0.035 | 0.095** | -0.048* | 10.000** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.034 | 0.001 | 0.043 | 0.021 | ||

| N | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | 1800 | |

| **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | |||||||

| *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). | |||||||

It is clear that the correlations of satisfaction are significant for all domains: metacognitive p<0.05 (n=0.002), cognitive p<0.05 (n=0.034), motivational p<0.05 (n= 0.001), behavioral p<0.05 (n= 0.043) (SPSS AMOS).

It is also clear that the correlations of strategic excellence are also significant for all domains: metacognitive p<0.05 (n=0.001), cognitive p<0.05 (n=0.034), motivational p<0.05 (n= 0.001), behavioral p<0.05 (n= 0.043).

Discussion

It is known that the IQ level is an objective indicator of mental ability that cannot be changed. IQ determines success at work. Emotional intelligence is one’s capability to maintain one’s emotions under strict control, as this has a great impact on teamwork as well as the atmosphere within the team. Unlike IQ, which is genetically inherent, a person can regulate and increase one’s emotional intelligence throughout his life. It is important to understand that a social skill score is as important to personal success as the ability to think logically or solve math problems.

At the same time a high level of one’s mental ability does not always determine work efficiency and is not used by the employer when hiring the individual. In many cases a person with a high IQ may turn out to be a tyrant who does not get along well with others, especially with the members of his very own team. That is why more and more large companies are turning to specialists in emotional intelligence for help: just search the Internet for "emotional intelligence for business" to be convinced of this.

Above all, strong emotional intelligence helps employees better understand customers. This means being able to quickly assess how the customer feels right now and choose the optimal behavior model. Ability to work with any mood of the client is a very important principle for maintaining loyalty. However, understanding emotions is only half the battle. It is important for an employee not only to understand them, but also to be able to respond in a friendly manner, without aggression. Because correctly counting an emotion and adjusting your behavior is an ideal method for quickly settling a conflict. In addition, for this it is not at all necessary to act with the "whip" method. It is much more effective to surprise the team, motivate it and show the concrete benefits that emotional intelligence will bring to each of the employees. Emotions interfere with work in the event that they are not vented or presented out into the open. This leads to the development of a feeling of dissatisfaction and even fear for the future. If the individual gets angry, then the logic of the individual is blurred, with the latter feeling sad and even depressed. This forces one to miss many important things in life, especially joy and happiness. The importance of EQ to individual efficiency and company success is beyond question. As the experience of foreign countries shows, the connection between business success and emotional intelligence is obvious, so it is definitely worth developing this ability!

References

Alqatanani, A. (2017). Do multiple intelligences improve EFL students critical reading skills?SSRN Electronic Journal, 10.

Al-ZoubiI, S., & Al-Adawi, F.A. (2019). Effects of instructional activities based on multiple intelligences theory on academic achievement of Omani students with dyscalculia. Journal for the Education of Gifted Young Scientists, 7.

Ang, S., & Van Dyne, L. (2015). Conceptualization of cultural intelligence: Definition, distinctiveness and nomological network. In: Handbook of Cultural intelligence: Theory, Measurement and Applications, Ang, S. and L. Van Dyne (Eds.), Routledge, New York.

Caligiuri, P., & Tarique, I. (2009). Predicting effectiveness in global leadership activities. Journal of World Business, 44.

Crowne, K.A. (2008). What leads to cultural intelligence? Business Horizons, 51, 5.

Fee, A., Gray, S., & Lu, S. (2013). Developing cognitive complexity from the expatriate experience: Evidence from a longitudinal field study. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 13.

Ferrero, M., Vadillo, M.A., & Leon, S.P. (2021). A valid evaluation of the theory of multiple intelligences is not yet possible: Problems of methodological quality for intervention studies, Intelligence, 88.

Flaherty, J.E. (2015). “The effects of cultural intelligence on team member acceptance and integration in multinational teams. (2nd Edition),” In: Handbook of Cultural intelligence: Theory, Measurement and Applications, Ang, S. and L. Van Dyne (Eds.), Routledge, New York.

Gregory, R., Prifling, M., & Beck, R. (2009). The role of cultural intelligence for the emergence of negotiated culture in IT offshore outsourcing projects. Information Technology & People, 22.

Hampden-Turner, C., & Trompenaars, F. (2006). Cultural intelligence: Is such a capacity credible? Group & Organization Management, 31.

Huang, J.L., Curran P.G., Keeney J., Poposki E.M., & DeShon R.P. (2012). Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27, 1.

Jackson, T. (2013). From human resources to human capital, and now cross-cultural capital. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 13.

Jordan, P.J., Ashkanasy, N.M., & Hartel, C.E.J. (2002). Emotional intelligence as a moderator of emotional and behavioral reactions to job insecurity. Academy of Management Review, 27.

Livermore, D. (2009). Cultural intelligence: Improving your CQ to engage our multicultural world. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic.

MacNab, B.R., & Worthley, R. (2012). Individual characteristics as predictors of cultural intelligence development: The relevance of self-efficacy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36, 1.

Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H.C. (2013). Assessing cross-cultural competence: A review of available tests. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 6.

Pashler, H., Rohrer, D., Abramson, I., Wolfson, T., & Harris, C.R. (2016). A social priming data set with troubling oddities. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 38.

Perrinjaquet, A., Furrer, O., Usunier, J.C., Cestre, G., & Valette-Florence, P. (2007). A test of the quasi-circumplex structure of human values. Journal of Research in Personality, 41.

Peterson, B. (2018). Cultural intelligence: A guide to working with people from other cultures. Place of publication not identified: Across Cultures.

Ramalu, S.S., Rose, R.C., Kumar, N., & Uli, J. (2010). Doing business in global arena: An examination of the relationship between cultural intelligence and cross-cultural adjustment. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 15.

Rockstuhl, T., Seiler, S., Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., & Annen, A. (2011). Beyond General Intelligence (IQ) and Emotional Intelligence (EQ): The role of Cultural Intelligence (CQ) on crossborder leadership effectiveness in a globalized world. Journal of Social Issues, 67, 4.

Tarique, I., & Takeuchi, R. (2008). Developing cultural intelligence: The role of international nonwork experiences. In Ang S and Van Dyne L (Eds) Handbook of Cultural Intelligence. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Templer, K.J., Tay, C., & Chandrasekar, N.A. (2006). Motivational cultural intelligence, realistic job preview, realistic living conditions preview, and cross-cultural adjustment. Group & Organization Management, 31.

Thomas, D., & Inkson, K. (2017). Cultural intelligence : Surviving and thriving in the global village. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Thomas, D.C., Stahl, G., Ravlin, E.C., Poelmans, S., Pekerti, A., Maznevski, M., & Au, K. (2012). Development of the cultural intelligence assessment. In Mobley (ed.). Advances in global leadership. Bingley, Yorks: Emerald Group.

Thomas, D.C., Liao, Y., Aycan, Z., Cerdin, J.L., Pekerti, A.A., Ravlin, E.C., Stahl, G.K., & van de Vijver, F. (2015). Cultural intelligence: A theory-based, short form measure. Journal of International Business Studies, 46, 9.

Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Koh, C. (2009). Cultural intelligence: Measurement and scale development. In Moodian MA (Ed) Contemporary leadership and Intercultural competence: Exploring the cross-cultural dynamics within organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Vedadi, A., Kheiri, B., & Abbasalizadeh, M. (2010). The relationship between cultural intelligence and achievement: A case study in an Iranian company. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 3.

Ward, C., Fischer, R., Lam, F.S.Z., & Hall, L. (2009). The convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of scores on a self-report measure of cultural intelligence. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69.

Ward, C., Wilson, J., & Fischer, R. (2011). Assessing the predictive validity of cultural intelligence over time. Personality and Individual Differences, 51.

Yusof, H.M., Kadir, H.A., & Mahfar, M. (2014). The role of emotions in leadership. Asia Social Science, 10, 10.

Received: 07-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-10566; Editor assigned: 09-Feb-2022, PreQC No JLERI-21-10566 (PQ); Reviewed: 23- Feb-2022, QC No. JLERI-21-10566; Revised: 05-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-10566 (R); Published: 19-Mar-2022.