Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 5

Organizational Justice and Employees Knowledge Sharing Behavior in Pakistan: Moderating Effect of Perceived Organizational Support

Abdul Majeed, University of the Punjab

Iqra Shahzadi, University of the Punjab

Javariya Javed, University of the Punjab

Adeel Jahangir, Superior University

Abdul Rasheed, University of the Punjab

Abstract

This study aims to investigate the impact of organizational justice (distributive, procedural, interactional) and organizational commitment on employees’ knowledge sharing behavior by applying the equity theory in emerging countries, particularly Pakistan. Also, this study investigates the moderating effect of perceived organizational support on the studied relationship. The data were collected from 365 employees of service sectors such as the telecommunication organizations in Lahore, Pakistan, using a self-administered questionnaire. The study used the quantitative method to test the theoretical model and proposed hypotheses empirically. The empirical results of partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) revealed that procedural justice and organizational commitment positively impact knowledge-sharing behavior. However, distributive justice and interactional justice were found insignificant with knowledge-sharing behavior. Next, the moderating effect of perceived organizational support significantly influences the association between distributive justice, interactional justice, organizational commitment, and knowledge sharing behavior. The findings of this study may help the organizations to improve employees’ commitment to the firm by ensuring fairness in procedures and resources. Likewise, it may help managers to create a sense of equality among employees, resultantly they share their knowledge and experience with team members as well as with other personnel of the organization.

Keywords

Organizational Justice, Organizational Commitment, Perceived Organization Support, Knowledge Sharing Behavior, PLS-SEM, Pakistan.

Introduction

Employee retention is considerable for organizations since if the employee wants to leave or leave the workplace resultantly the firms will bear a cost in form of competencies, experience, financial terms, and valuable knowledge (Ponnu & Chuah, 2010; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Because loyal, satisfied and motivated employees play an essential role in the firms’ competitiveness and market place. Also, the employees are considered the most valuable assets of an organization (Imamoglu et al., 2019). Consequently, workers' attitude and behavior towards the organization have proved utmost significant predictors affecting the company's performance. Organization fairness refers to employees’ trust in the organization as well as the company process (Iqbal & Ahmad, 2016; Imamoglu et al., 2019). In addition, the justice perception of employees is a significant predictor of employee’s attitudes and behavior about the organization (Silva & Caetano, 2014; Imamoglu et al., 2019).

Organizational commitment permits employees to add values to the firm by making continuous efforts and work in the organization (Mowday et al., 1979; Imamoglu et al., 2019). In this context, by providing the atmosphere of harmony and teamwork within the firm, both organizational commitment and organizational justice have empowered companies to achieve more outcomes from their employees. Employees with perceived fairness have a greater desire to share experience and skills in this regard, and they have also strengthened organizational knowledge. Presently, firms are more focused to manage their employees with justice, due to the increasing awareness of government regulations about employee rights (Akram et al., 2017). In fact, today's economy is a highly knowledgeable and innovation-oriented economy, therefore in the contemporary business environment, justice/fairness is highly needed. The employees’ competitive knowledge is seeming to be more important for business survival in the competitive and technology-based market. So, it is essential for an organization to investigate the predictors that promote or hinder knowledge sharing in the organization (Akram et al., 2017). Instead of many other factors, perceived justice is the most influential predictor of employees’ behavior in the organization. Organizational justice and organizational commitment make it possible for a successful organization to achieve high performance and attain competitive advantage.

Prior study has examined that knowledge-sharing behavior the link between psychological ownership, and employees’ (Hameed et al., 2019). This study has assumed that this relationship can be strengthened by perceived organizational support (POS) because this correlation is not seeming free from boundary-condition. POS alludes to the employees’ belief that companies consider their well-being and take good care of them (Eisenberger et al., 2001). POS has a positive impact on workplace outcomes (Erdogan & Enders, 2007). Consistently, King & Marks, (2008) and Castaneda et al., (2016) have investigated that POS positively relates to knowledge sharing behavior. Previous study investigated that POS as a linking mechanism that strengthens the relationship between the company and workers (Allen & Shanock 2013). The knowledge-sharing behavior of employees is influenced by POS and closely related to those employees who are more conscious about their job security (Bartol et al., 2009). In addition, earlier researches highlighted knowledge sharing behavior is affected by POS (Anand et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2006). Hence, the authors interested examine the moderating effect of perceived organizational support between the association of organizational commitment, dimension of organizational justice (distributive, procedural, interactional), and knowledge sharing behavior will make an important contribution to the literature. The correlations between the exogenous variables and endogenous variable would be stronger at the higher level of POS and contrary to this.

Hameed et al., (2019) was concentrated on how workers should be empowered to share their expertise with other employees. Management studies of (Tea Moon, 2015; Akram et al., 2017) examined the association of organizational justices and employees’ knowledge sharing behavior. Although there are several studies on this concept (Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019; Li et al., 2017; Akram et al., 2017; Han et al., 2010; Van Den Hooff & Ridder, 2004). But few researches have explored knowledge sharing behaviors is influenced by POS. (Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019; Castaneda et al., 2016; Anand et al., 2007). Therefore, this research examining the moderating role of perceived organizational support among the context variables in order to strengthen the explanatory power of theoretical framework. As a result, organizations will work for the well-being of their employees, and workers will feel more job security and share their knowledge, experiences and innovative information and the organization get successful.

The present study has two main objectives: First, the present research concerned to examine the influence of organizational justice dimensions (interactional, procedural, distributive) and organizational commitment on employee knowledge sharing by applying the equity theory (Adams, 1965). It may contribute to management growth in developing countries like Pakistan. Secondly, the study concerned to assess the interactional influence of POS among the associations of organizational commitment, organizational justice dimensions, and knowledge sharing. For investigating how POS stimulate or encourage employees’ knowledge sharing behavior. Based on the aforementioned discussions, the study address questions which are unexplored in an emerging country. RQ1: Does knowledge sharing behavior affected by organizational commitment and organizational justice dimension (interactional, procedural, distributive)? RQ2: Does POS moderate the association of knowledge sharing behavior, organizational commitment, organizational justice dimension (interactional, procedural, distributive)?

The study has two main theoretical contributions: First, the present research examines the influence of organizational justice dimension (interactional, procedural, distributive) and organizational commitment on employees’ knowledge sharing behavior by applying the equity theory (Adams, 1965) in-service sector relating to developing countries like Pakistan. Second, the current research examines the moderating role of POS among the relationship of knowledge sharing behavior, organizational commitment, organizational justice dimension (interactional, procedural, distributive) to strengthen an explanatory power of theoretical model. The study has four main practical contributions: A) the practitioners can use these findings to improve their workplace environment by getting improvement in distribution perks like salary, incentives, and employee promotion. B) HRM practices can improve employee perceptions regarding a sense of ownership and arrange training in the organizations through which they can learn for knowledge sharing behavior. C) This study can be helpful for organizations in maintaining justice in the organization procedures that will be leading to employee well-being, work engagement, and firm performance. D) The finding of this study might be helpful for the management can create an environment in which employees would be work with more commitment.

This research paper has structured as follows. First, theory related literature review is discussed, later on, the hypotheses formation section. Section three consists of the methodology of the study. Results are discussed in section four. The final section includes discussion, study implications, limitations, and future scope.

Literature Review

Adams (1965) Equity Theory

Is there anything that motivates me to work? Yes, as per the equity theory of (Adams, 1965), the equitability motives employees to work and inequitably demotivates employees to work. Equity theory has two key components: Firstly, Input and output. Employees matched their job inputs with outputs ratio. If they perceive inequality, they will try to eliminate inequality. Which can be reduced employee’s productivity and compromise their job quality. Additionally, most of the time inequality makes absenteeism leading to job resignation (Greenberg, 1999).

In any social situation in which exchange takes place, the equity theory can be applied, for instance, between the organization and his employees, between a man and his wife, and between the coach and football team etc. The equity theory can be applied to any social situation in which exchange occurs (e.g., between an employee and his employer, between football team mates, and between a man and his wife). There is a risk that when two people share something, one or both would believe that the share something was inequitable. This circumstance is most of the time happened when a person exchanges his services for salary (Adams, 1963). The relationship between inputs and outcomes depends upon the perception of the individual, whether a social exchange is treated inequitable or equitable (Walster et al., 1973; Adams & Freedman, 1976; Adams, 1965; Adams, 1963). Adams, (1965) defined inequality as “inequality exists for individuals if they understand that there is an unequal ratio of their outcomes to inputs and the ratio of other outcomes to other inputs”.

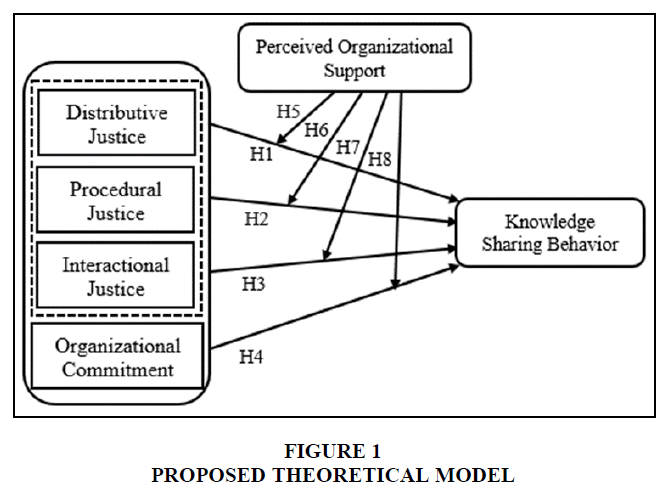

Consistently, organizations should consider the (Adams, 1965) equity theory at their workplace. This study is based on equity theory as this is an exchange of input and output. According to the equity theory, if there is any in-equitability in the organization, then the organization should create a justice environment. When an individual considers he/she is being treated with justice in the workplace, and he/she is giving input and receives a comparable output (pay and compensation) resultantly he would feel that the resources are distributed equally. Organizational justice relates to the perception of workplace equality among employees (Byrne & Cropanzano, 2001; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Employees who are working in the workplace put inputs (experience, efforts, knowledge, and skills) and they expect some outputs from the organization (Pay, bonuses, seniority, and fairness in the resources). An exchange is found in the organization between the employees and employer. Workers expect that there should be justice in all the processes of the organization. Justice has three dimensions; distributive, procedural, and interactional (Colquitt, 2001). When workers attain outputs as per inputs and feel justice in the workplace, then they will work more committedly to the organization. This relationship is based on an exchange. Based on the aforementioned rationale, the current study employed the (Adams, 1965) equity theory to test the theoretical framework (Figure 1).

Hypotheses Development and Theoretical Model

Organizational justice

Organizational justice relates to the perception of workplace equality among employees (Byrne & Cropanzano, 2001; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Organizational justice is an employees’ evaluation regarding managerial conduct in terms of ethics and morality (Cropanzano et al., 2007; Imamoglu et al., 2019), attitude and behavior of employees are directly affected by these perceptions (Silva & Caetano, 2014; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Organizational justice is the subjective expectations of employees about justice in working links (Cropanzano et al., 2001). The distributions of resources, incentives, outputs within the organization are classified underneath the term of justice (Notz & Starke, 1987; Hameed et al., 2019). Organizational justice has three dimensions i.e. interactional, procedural, and distributive (Hameed et al., 2019; Colquitt et al., 2001). It has been proven that from past studies, knowledge sharing is positively affected by organizational justice (Imamoglu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2017; Akram et al., 2017).

Distributive justice

It is relating to the perceived justice of the outcomes achieved by workers (Cropanzano et al., 2007; Imamoglu et al., 2019). In line with, distributive justice is an employees' perception, either they are punished or appreciated only for what they do, although if anyone who wants to work in the same organization would be expected to treat equitably for the distribution of outcomes (Rahman et al., 2016; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Many studies described that distributive justice is an exchange of inputs (employees given to the organization) and outcomes and resources (employees received from the organization) based on justice or fairness (Nowakowski & Conlon, 2005; Tamta & Rao, 2017; Akram et al., 2017; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Indeed, perceived justice is a "glue" that encourages workers to work collaboratively, and collaborative work causes information sharing (Cropanzano et al., 2007) and Imamoglu et al., 2019). In addition, if employee contributions are fairly assessed and rewarded, they are more interested in sharing personal knowledge with others to improve the organizational performance and accumulate knowledge in order to be truly capable of performing their own tasks (Ibragimova et al., 2012; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Previous studies showed a positive significant link between distributive justice and knowledge sharing (Mcpherson, 2004) p.743. A study in the telecommunication sector in china in 2016 claimed that knowledge sharing behavior is affected by distributive justice (Akram et al., 2017). Past studies also claimed that distributive justice is significantly correlated to knowledge sharing (Akram et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Hence, we propose the next hypothesis.

H1 Distributive justice has significant influence on knowledge sharing behavior.

Procedural justice

It is the perceived fairness of the method whereby outcomes are assessed (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Procedural justice is indeed the fair treatment of organizational processes as well as makes sure they must be impartial, coherent, precise, corrective, ethical, and representative (Bies and Moag 1986; Akram et al., 2017). In this respect, they perceive fairness when employees participate in the process, although they are not happy with the outcome (Chen et al., 2015; Imamoglu et al., 2019). The theory of procedural justice focuses mainly on the effect of decision-making processes on the perception of fairness (Thibaut et al., 1975). Employees should not assume each decision outcome to always be favorable because they recognize that many competing interests and issues must be taken into account by decision-makers (Mcpherson, 2004) page 745. Rather, they are seeking assurance that decision-makers may give them proper fairly favorable long-term decision outcomes. This assurance is provided by the presence of fair decision-making processes (Mcpherson, 2004) page 745. In the case, where organizational procedures will be seen as fair, employees seem to be open to sharing ideas, experiences, and knowledge (Ibragimova et al., 2012; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Thereby, to strengthen the sense of organizational affiliation, employees could tend to link more organizational property rights towards their own knowledge. Employees may want to share knowledge as it helps them feel proud or a part of the company (Mcpherson, 2004) page 745. Previous studies pointed out procedural justice positively relates to knowledge sharing (Mcpherson, 2004) page 743. Procedural justice significantly correlates to knowledge sharing in the telecommunication sector of china (Akram et al., 2017). Therefore, this research proposes the next hypothesis.

H2 Procedural justice has significant influence on knowledge sharing behavior.

Interactional justice

Interactional justice is an organizational process that refers to the perceived fairness of interpersonal interaction (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Imamoglu et al., 2019). When managers provide an equitable attitude and behavior towards staff through processes, staff are possible to consider interactional justice (Akram et al., 2017; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Interactional justice reflects the perception of the staff about unbiased inter-personal treatment, which they obtain from decision-makers within this organization (Akram et al., 2017). Social exchange theory may explain the inspiring principle of interactive fairness for employees. The employees feel kind treatment when they are respected and appreciated through interactive fairness, in turn, they would be willing to exchange their personal knowledge with other employees to improve the organizational performance. Thus, interactive fairness positively correlates with the social intention of knowledge sharing. Communication among managers and subordinates along with a sincere communication attitude may contribute to the positive perception of interactive justice. Revive the optimistic perception to be valued and trusted by workers, resultantly social intention would be increased (Liao et al., 2011). Knowledge sharing is affected by positive perception of interactional justice (Akram et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Hence, this research conjectured the subsequent hypothesis.

H3 Interactional justice has significant influence on knowledge sharing behavior.

Organizational commitment

OC refers to a power that encourages employees to work towards certain objectives (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001; Imamoglu et al., 2019). OC is used as a strength of the participation and identity of an employee of a particular company (Porter et al., 1974; Li et al., 2017). OC is an employees' psychological state that binds him to the organization, which leads to constructive organizational outcomes Allen & Meyer, (1990). If an employee would like to pursue working with a particular organization, they would like the organization to be successful. For the reason that workers would also get profit from it if the organization is successful. The said benefit could be a rate of pay, the commencement of the present situation, or dignity. To this end, employees are working towards the achievement of organizational objectives. Furthermore, employees with higher commitment are willing to succeed in the organization, and knowledge sharing seems to be the ideal route to use it because knowledge seems to be the most important predictor for contemporary organizations (Li et al., 2017; Imamoglu et al., 2019). Prior researches of (Li et al., 2017 investigated that organizational commitment positively relates with knowledge sharing behavior (Lin, 2007a, b; Van den Hooff & De Ridder, 2004;), demonstrating that employees who would be more committed to the company seem to be more interested in sharing knowledge to their supervisors/coworkers (Wang & Noe, 2010) pointed out the employees' perception of fairness correlate to knowledge sharing by affecting employee's commitment to the organization (Li et al., 2017). Thus, this study suggests the next hypothesis.

H4 Organizational commitment has significant influence on knowledge sharing behavior.

POS as a moderator

Previous studies have developed an association between organization justices and knowledge sharing behavior through psychological ownership. The authors of this study assume that this association does not free from boundary-condition which is perceived organization support (POS). POS refers to the belief of employees that companies take good care of them as well as consider their well-being (Eisenberger et al., 2001). Erdogan and Enders, (2007) highlighted that POS positively relates to workplace outcomes. Many scholars investigated that knowledge sharing behavior is affected by POS (King & Marks, 2008; Castaneda et al., 2016). POS is a binding mechanism that strengthens the relationship between employees and the organization (Allen & Shanock, 2013). For those employees who want job security, POS and knowledge sharing behavior are closely related for them (Bartol et al., 2009). Prior studies of Anand et al., (2007) and Lee et al., (2006) examined POS is a significant predictor of knowledge-sharing behavior. POS plays a key role as employees feel that the organization plans organizational benefits for their welfare, not even as an obligation. Therefore, this study interested to investigate the moderating effect of POS between the association of organizational justices (interactional, procedural, distributive), organizational commitment and knowledge sharing behavior. The correlations between the exogenous constructs and outcome variable would be stronger at the higher level of POS and contrary to this. Hence, this study proposes the following hypotheses.

H5 POS strengthens the connection of distributive justice and knowledge sharing behavior.

H6 POS strengthens the connection of interactional justice and knowledge sharing behavior.

H7 POS strengthens the connection of procedural justice and knowledge sharing behavior.

H8 POS strengthens the connection of organizational commitment and knowledge sharing behavior.

Methodology

Data Collection and Procedures

The present research used a quantitative approach to test the recommended hypotheses. The data was collected from the employees of the service sector (lower-level management, middle level, and top-level management) over the period of three weeks in working days on August 2020, using a self-administered questionnaire. The study includes merely three major service industries; transport industry, telecommunication industry, and consulting firms, convenience sampling technique was used. There were a total of 430 target respondents, out of which 390 questionnaires were completed and returned, of which 25 questionnaires were found as unusable and discarded. Net responses of 365 showing a response rate of 84.88%. The sample size was calculated using the G*power software suggested by (Faul et al., 2007). According to (Roscoe, 1975) as cited in (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016), explained the sample size must be in-between 30 to 500. The sample size is meet the threshold values explained by the aforementioned researchers.

Table 1 shows the respondents’ demographic profile. A total of 365 respondents have participated voluntarily in this study. Of which 71.1% (260) were males, and 28.9% (105) were females. Relating to age, 28.9% (105) participants were aged 20-35 years old, more than half of respondents 60% (219) were aged 26-30 years old, the least amount of participants 2.2% (8) were aged of 31-35, next 8.9% (33) participants were aged of 36 years or above. About job experience, most respondents 60.4% (220) were experienced 3-5 years, followed by 36% (131) participants having 3-5 years' experience, the least amount of participants 0.4% (3) having job experience of 11-15 years, next 3.1% (11) participants were experienced 16 years or above. Regarding education, the least amount of respondents 19.6% (72) having a master's degree, however more than half of respondents 56% (204) holding a bachelor's degree, followed by 24.4% (89) participants were MPhil. About average monthly income, highest respondents 43.1% (157) were earning 91,000 PKRs. or above, followed by 39.6% (145) respondents were earning 30,000-50,000 PKRs, then 15.6% (57) participants were earning 51,000-70,000 PKRs, a least amount of participants 1.8% (6) were earning 71,000-90,000 PKRs.

| Table 1 Demographic Information | |||||

| Variables | Frequencies | Percentages | Variables | Frequencies | Percentages |

| Gender | 11-15 Years | 3 | 0.4% | ||

| Male | 260 | 71.1% | 16 Years-Above | 11 | 3.1% |

| Female | 105 | 28.9% | Education | ||

| Age (Years) | Bachelors | 72 | 19.6% | ||

| 20-25 | 105 | 28.9% | Masters | 204 | 56% |

| 26-30 | 219 | 60% | M.Phil. | 89 | 24.4% |

| 31-35 | 8 | 2.2% | Average Monthly Income | ||

| 36-Above | 33 | 8.9% | 30,000-50,000 PKRs. | 145 | 39.6% |

| Experience | 51,000-70,000 PKRs. | 57 | 15.6% | ||

| 3-5 Years | 220 | 60.4% | 71,000-90,000 PKRs. | 6 | 1.8% |

| 6-10 Years | 131 | 36% | 91,000 PKRs.-Above | 157 | 43.1% |

Measures

The questionnaire was divided into two sections, the first section was regarding demographic information of the participants like age, gender, experience, management levels, education, and average monthly income. The questions about participants’ perceptions of organizational justice (interactional, procedural, and distributive) at workplace, was contained in section two. The 43 items were used for measuring the context variables. Distributive justice was measured by five items, procedural justice was evaluated by six items, and interactional justice was assessed by nine items, these all items was adopted from (Niehoff & Moorman, 1993). Organizational commitment was estimated by nine items adapted from (Jaros, 2007). Perceived organizational support was gauged by seven items rented from (Eisenberger et al., 1986). Knowledge sharing was assessed by seven items adapted from (Lin, 2007). To measure the items of corresponding variables, a standardized five-point Likert scale was used to organize the scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

Analytical Method

Path-modeling partial least squares (PLS), a variance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) tool, was used in this study to evaluate the model (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012). PLS enables researchers to simultaneously evaluate relationships among certain constructs (inner model) and can assess reliability and validity of the factors of conceptual framework (outer model) (Barroso et al., 2010). Three main reasons to use the PLS statistical software: Firstly, the objective of this research is to predict dependent variables (Chin, 2010). Second, the research model is complex in the form of hypothesized relationships (direct and indirect or moderating effects). Finally, this study utilizes latent variable scores for predictive relevance in the subsequent analysis (Hair et al., 2011). Therefore, researchers employed the PLS Smart 3.0 software Ringle, et al., (2005).

Results

Reliability and Validity Assessment

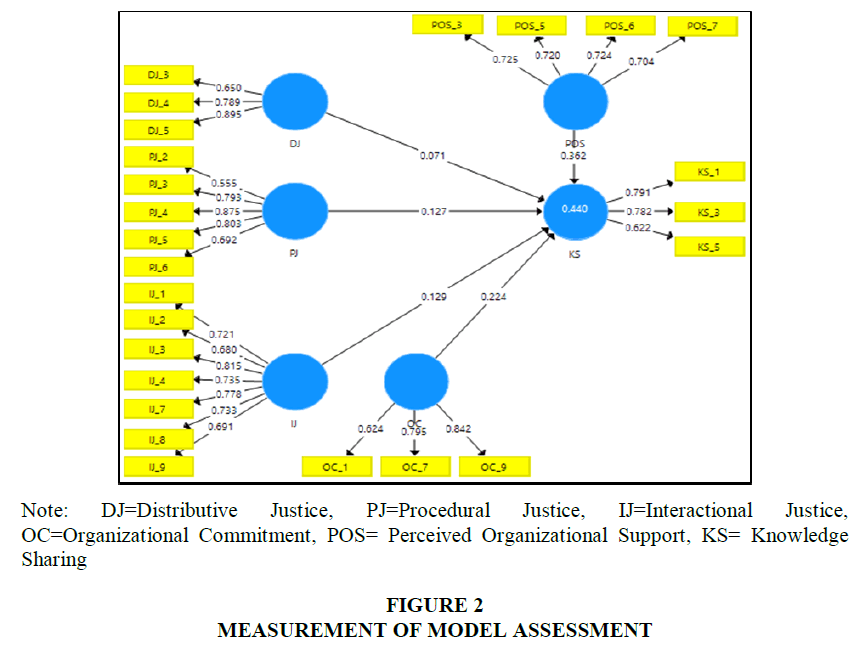

Measurement of the model was executed through the reliability and validity assessment, composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach alpha (CBA) techniques did use to check the reliability of the constructs (Figure 2). According to (Robinson et al., 1991; Malhotra, 2010; Hair et al., 2010) the values of CBA should be more than 0.7, it looks more adequate. The CBA value over 0.80 is treated as good, more 0.70 is satisfactory, and equal to or less than 0.60 is taken as poorly advised by (Hair et al., 2010). However, as Table 2 showing CBA values of all six factors are more than 0.7, hence reliability is satisfactory. As stated by (Nunnally, 1978; Gefen et al., 2000) the value of the CR should be more than the threshold value of 0.7. CR has considered as more exact reliability (Chin & Gopal, 1995). As Table 2 is presenting the value of the CR is above 0.7, therefore CR is considered as more reliable.

| Table 2 Measurement of Model | Reliability and Validity | ||||

| Variables | Ranges of Outer Loading | Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

| Distributive Justice | 0.650-0.895 | 0.719 | 0.825 | 0.616 |

| Procedural Justice | 0.555-0.875 | 0.811 | 0.864 | 0.565 |

| Interactional Justice | 0.691-0.815 | 0.863 | 0.893 | 0.544 |

| Organizational Commitment | 0.624-0.842 | 0.707 | 0.801 | 0.577 |

| Perceived Organizational Support | 0.704-0.725 | 0.747 | 0.810 | 0.516 |

| Knowledge Sharing Behavior | 0.622-0.791 | 0.819 | 0.778 | 0.541 |

The outer loading of items of the variables should be above 0.5 suggested by (Hair Jr et al., 2016). As per Table 2, these values are above the cut-off value of 0.5, while some items were cross-loaded whose loading values were less than the cut-off point 0.5. The deleted items were shown in appendix 1. The value of average extracted value (AVE) should be more than 0.5 suggested by (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Dillon & Goldstein, 1984; Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In Table, values of AVE more than recommended cut-off point 0.5, hence convergent validity is considered acceptable.

Discriminant Validity

To evaluate the discriminant validity, new and modern criteria have been used suggested by (Henseler et al., 2015). The Fornell-Larckher criterion is a technique that is a more suitable method to check the discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). But this technique has some deficiencies in various situations, therefore we employed a further approach Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) through which we can evaluate discriminant validity successfully (Ul et al., 2021). We used these two techniques for evaluating the discriminant validity, most of the researchers have applied these techniques (Henseler et al., 2016; Neneh, 2019). The square root of the values of AVE is above all the cross-correlations among the context variables (see Table 3). The bold diagonal values in the parallel rows and columns are substantially higher than the off-diagonal ones, hence discriminant validity is satisfactory for the measurement of the model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Furthermore, the HTMT technique is the most modern technique which is used to evaluate the discriminant validity which is projected by (Henseler et al., 2015). Thus, this technique has been used to check the discriminant validity and values should be less than 0.90 as proposed by (Gold et al., 2001). As table 4 is presenting the all values are less than the cut-off point in the corresponding rows and columns.

| Table 3 Discriminant Validity | Fornell-Larcker Criterion | ||||||

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1) Distributive Justice | 0.742 | |||||

| 2) Interactional Justice | 0.353 | 0.719 | ||||

| 3) Knowledge Sharing Behavior | 0.412 | 0.725 | 0.767 | |||

| 4) Organizational Commitment | 0.698 | 0.646 | 0.683 | 0.724 | ||

| 5) Procedural Justice | 0.278 | 0.515 | 0.295 | 0.430 | 0.756 | |

| 6) Perceived Organization Support | 0.438 | 0.672 | 0.636 | 0.698 | 0.469 | 0.719 |

| *Bold diagonal elements are square root of AVE | ||||||

| Table 4 Discriminant Validity | Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | ||||||

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1) Distributive Justice | ||||||

| 2) Interactional Justice | 0.253 | |||||

| 3) Knowledge Sharing Behavior | 0.419 | 0.593 | ||||

| 4) Organizational Commitment | 0.318 | 0.657 | 0.821 | |||

| 5) Perceived Organization Support | 0.395 | 0.402 | 0.819 | 0.550 | ||

| 6) Procedural Justice | 0.271 | 0.639 | 0.559 | 0.663 | 0.310 | |

Structural Model

After the assessment of the measurement of a model, the structural equation modeling (SEM) technique has been used to empirically test the proposed hypotheses (Figure 3). This technique has been employed using bootstrapping in Smart PLS computer version 3 (Ringle et al., 2005). The assessment of structural model based upon t-values, p-values, path coefficients, and standard errors. This study tested a total of eight hypotheses including moderation in the studied model, out of which five hypotheses (H2, H4, H5, H7, and H8) found to be significant and are supported (see Table 5 and 6). The hypotheses are determined significant and supported based upon a critical ratio (p<0.05). Hence, significant and supported hypotheses are under the critical ratio (p<0.05). The influence of procedural justice (β2=0.127, p<0.01) and organizational commitment (β4=0.224, p<0.01) on Knowledge Sharing behavior. Contrarily to this H1 and H3 are not supported. On the other hand, the results of moderating effect of POS among the context variables are revealed in Table 6 presenting the influence of distributed justice and POS (β5= (-0.17), p<0.05), interactional justice, and POS (β7=0.232, p<0.05), organizational commitment and POS (β8=0.178, p<0.05) on Knowledge Sharing behavior. Contrary to this, H6 is found to be insignificant.

| Table 5 Hypotheses Testing | ||||

| Direct Paths | Path Coefficient | T-value | Decisions | |

| H1 | Distributive Justice → Knowledge Sharing Behavior | 0.071 | 1.033 | Not Supported |

| H2 | Procedural Justice → Knowledge Sharing Behavior | 0.127** | 2.898 | Supported |

| H3 | Interactional Justice → Knowledge Sharing Behavior | 0.129 | 1.681 | Not Supported |

| H4 | Organizational Commitment → Knowledge Sharing Behavior | 0.224** | 2.399 | Supported |

| Note: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.000 | path coefficient=> standardized beta | ||||

| Table 6 Interactional Effects of POS | ||||

| Interactional Paths | Path Coefficient | T-value | Decisions | |

| H5 | Distributive Justice * Perceived Organizational Support → Knowledge Sharing Behavior | -0.170* | 2.141 | Supported |

| H6 | Procedural Justice * Perceived Organizational Support → Knowledge Sharing Behavior |

-0.096 | 1.299 | Not Supported |

| H7 | Interactional Justice * Perceived Organizational Support → Knowledge Sharing Behavior | 0.232* | 2.156 | Supported |

| H8 | Organizational Commitment * Perceived Organizational Support → Knowledge Sharing Behavior | 0.178* | 1.952 | Supported |

Discussion

This study examined the effect on knowledge sharing behavior of organizational commitment and organizational justice dimensions (interactional, procedural and distributive), with the moderating effect of POS among exogenous constructs and outcomes variable in the service sector of Pakistan. The standardized coefficient beta was used to assess the effects of explanatory predictors on dependent variable, as posited in the study hypotheses. The study findings revealed that procedural justice, organizational commitment and perceived organizational support have the greatest impact on knowledge sharing behavior. However, distributive justice and interactional justice make no contribution to the knowledge sharing behaviors of employees.

Hypothesis 1 the influence of distributive justice on the knowledge sharing behavior was seen as an insignificant, however distributive justice produced the opposite results. Therefore, H1 is rejected. Which means that in Pakistani culture it seen that there was no fairness in work schedule, the employees thought that salary which they received was not fair according to their services, employees considered that overall rewards they were receiving from the organizations were not distributed with justice and employees perceived that job responsibilities were not fair in the workplace. Empirical results are inconsistent with previous studies (Akram et al., 2017; Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019; Li et al., 2017). Many scholars investigated distributive justice has moderate positive impact on knowledge sharing behavior in telecommunication sector in China (Akram et al., 2017), in industrial and service sector in Spain (Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019), in education sector in Taiwan (Mcpherson, 2004) p.743, and in energy sector in China (Li et al., 2017). While, distributive justice has negative impact on knowledge sharing behavior in IT sector in USA (Ibragimova et al., 2012). The findings would be helpful for explaining the facts about Pakistani employees perceive distributive justice during job responsibilities, and they are treated with dignity and respect, while making job decision. They are more motivated for sharing their work related valuable knowledge.

Hypothesis 2 the impact of procedural justice on knowledge sharing behavior of employees was found to be significant. Hence, H2 is accepted. A possible explanation could be that employees may be thought general manager took all decisions with unbiased and equitable, they perceived that general manger got all accurate and correct information in decision making process. Employees' perception of justice or fairness about allocation of work, procedures, process, and time at workplace leads to knowledge sharing behavior in form of knowledge collection and knowledge donation. These findings are in line with the results of prior studies (Ibragimova et al., 2012; Akram et al., 2017; Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019 and Li et al., 2017). Many researchers investigated that procedural justice has positive influence on knowledge sharing behavior in IT sector in USA (Ibragimova et al., 2012), in telecommunication sector in China (Akram et al., 2017), in industrial and service sector (Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019), in education sector in Taiwan (Mcpherson, 2004), and in energy sector in China (Li et al., 2017). When someone has considered a process to be fairer, he will more tolerant about process consequences. Relating to knowledge sharing, this means individual believe that performance appraisal process is fairly treated, which leads to more knowledge sharing behavior of employees.

Hypothesis 3 the SEM analysis reveals that interactional justice was found to be insignificant with knowledge sharing behavior. Thus, H3 is rejected. A conceivable interpretation could be that in Pakistan culture many employees feel that their general manager do not treat with kindness and consideration. Employees perceived that they were not treated with dignity and respect. The behavior of general manger with their subordinates was not in truthful manner. Employees at workplace perceived that general managers do not clearly explain and engage in job decision.

Interactional justice describes as when an individual perceives the maximum of exchange between employees based on respect and understanding of the feelings of others in an organization. Where the environment is seen as equitable and just, individuals seem to be more willing to achieve the organizational goals (Staley et al., 2003; Ibragimova et al., 2012). These findings are in line with prior results (Ibragimova et al., 2012) they had found interactional justice do not influence knowledge sharing behavior in IT sector in USA. In contrast, we found some previous findings that are inconsistent with current results (Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019; Akram et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017). They investigated that knowledge sharing behavior significantly affected by interactional justice in telecommunication sector in China (Akram et al., 2017), in industrial and service sector in Spain (Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019), and in energy sector in China (Li et al., 2017). While, knowledge sharing behavior was being negatively influenced by interactional justice in IT sector in USA (Ibragimova et al., 2012).

Hypothesis 4, the results revealed that knowledge sharing behavior of employees significantly affected by organizational commitment. Therefore, H4 is supported. This can be attributed to face that employees feel happiness to be the part of the organization. Employees work for the organization with dedication. Employees perceive that organization considers their loyalty towards it. This findings support to the findings of previous studies (Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019; Li et al., 2017; Han et al., 2010; Lin, 2007a; Van Den Hooff & Ridder, 2004). They investigated knowledge sharing behavior positively influenced by organizational commitment in an industrial and service sector in Spain (Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019), and in energy service sector in China (Li et al., 2017), in high tech companies in Taiwan (Han et al., 2010). In addition, organizational commitment and tacit knowledge sharing significantly associated with each other in the context of education sector in Taiwan (Lin, 2007a). In line with, organizational commitment significantly related with knowledge sharing behavior in different five sectors; consultancy firms, financial services organizations, government department, education organization, technical service organization in Netherland (Van Den Hooff & Ridder, 2004).

POS as a Moderator

In this study perceived organizational support (POS) is used as moderator among organization justice dimensions (interactional, procedural, distributive) organizational commitment and knowledge sharing behavior. Empirical results examined POS moderates the association among organization justice dimensions (interactional, distributive), organizational commitment and knowledge sharing behavior. Hence H5, H7 and H8 are accepted. However, H6 is rejected (see Table 6). Hypothesis 5, distributive justice does not directly link with knowledge sharing in Pakistani context, but in the presence of POS as a moderator this path is found negative significant. Its possible reason could be that employees may be perceived work schedules are not fair in the workplace, they may perceived about pay/output which they have been receiving from the organization is not quite fair against work time/inputs, regarding organization support employees may be perceived organization does not stand behind the their problems, therefore they may not share their valuable knowledge and experience with others.

Hypothesis H7, interactional justice does not directly link with knowledge sharing in Pakistani context, but in the presence of POS as a moderator this path is found positive significant. A conceivable reason could be some employees may be perceived their senior manager treated them with dignity and respect in the workplace, in a result they feel more respect and more likely to share knowledge with other. In line with, organization creates a friendly environment and make polices for the employees in the workplace which supports to their problems, hence they share their knowledge and experience with others employees in order to achieve common goal of organization. Final hypothesis H8, POS as a moderator strengthen the relationship of organizational commitment and knowledge sharing. An imaginable explanation could be that employees may be perceived identical happy with organization, they are committed to the organizations' policies, they may do not want to change their job in future, hence they share more knowledge, expertise and information. Afterward, organization's performance will be boost up, and organization will work for employees' wellbeing, supports them and stand behind their problems.

However, hypothesis 6 procedural justice and knowledge sharing behavior found to significant in direct path, but in the existence of POS as a moderator this relationship is revealed insignificant. A possible explanation could be that some employees may be perceived general manager does not get the more accurate information for decision making and organization's polices may don’t compel to general managers when they take any decision. The employees may not allow to challenge or appeal their job in the workplace. They may feel strict environment that affect organization's performance. Previous studies investigated POS has positive impact on knowledge sharing behavior in industrial and service sector in Spain (Cugueró-Escofet et al., 2019) and in public sector organization in Colombia (Castaneda et al., 2016), and in management consulting firm in London, UK (N. Anand et al., 2007). In addition, POS has impact on knowledge sharing behavior concerning organizations that collect data for a wide US federal agency with the duty of providing and managing communications networks for the US Defense department component (King & Marks Jr, 2008).

Study Implication

The findings of the present study are equally important for organizations managerial perspective and theoretical perspective. This study has two main theoretical implications: First, present research investigated the effect on knowledge sharing behavior of organizational justice dimensions and organizational commitment in service sector by applying the equity theory in Pakistani context. This study contributed in the theoretical body of management knowledge to examine interactional justice and distributive justice found to be insignificant with knowledge sharing behavior, however knowledge sharing behavior significantly affected by procedural justice. In addition, organizational commitment and POS are found most significant influencing predictors of employees, knowledge sharing behavior. Second, present research examined the effect of POS as a moderator among the associations of organizational justices (interactional, procedural, distributive), organizational commitment and knowledge sharing behavior to strengthen the explanatory power of theoretical model. The findings revealed that distributive justice and interactional justice are found insignificant with knowledge sharing behavior, but in the presence of POS as a moderator shown to be significant. In line with, POS does not moderate between procedural justice and knowledge sharing behavior. In addition, the findings exposed POS strengthen the link between organizational commitment and knowledge sharing behavior.

This study has main three practical implications: Firstly, the organization and practitioners can use these findings to improve their practices in workplace environment. Distributive justice and interactional justice are found to be insignificant with knowledge sharing behavior due to not fair distribution policy of organizations in studied context, organization should revise distribution policy and improve their distribution perks (i.e. salary, incentives, bonuses, rewards and promotion plans) in order to encourage employees for knowledge sharing with other employees to improve organization performance. General Managers/seniors should interact with their sub-ordinates with dignity and respect in the workplace, this is directly related to knowledge sharing behavior because when employees feels disrespect by senior and not rewarded on merit, resultantly they reluctant to share their valuable knowledge, skills with others. Secondly, procedural justice has found to be significant with knowledge sharing behavior, so organization can strengthen their employees' perception of sense of ownership, and knowledge sharing with coworkers and team members. The general manager can use these findings to make unbiased job decisions, to make sure employees' concerns are heard before job decision and have collected complete and accurate information. In addition employees can also use these findings to challenge or appeal job decisions made by the general manger. Finally, as per the findings POS moderates between organization justices, commitment, and knowledge sharing. The organization should create a perception/sense in the mind of employees that organization stands behind your problems, organization should support employees through fairness and justice-based policies, should provide fairness in the procedures and compensation which will encourage to employees to share the knowledge (Hameed et al., 2019). Organizations should arrange training in order to employees can learn knowledge sharing behavior. HR managers should pay more attention to design the more attractive bonus policies to motivate their knowledge sharing which cores interested related knowledge (Whicker & Andrews 2004). The management should create an environment in which employees can work with more commitment and they can more share knowledge.

Limitations and Future Scope

The finding of this research are subject to some limitations need to be noted: Firstly, this research used a cross-sectional research design, although this design was used due to time and cost constraints, causality cannot be inferred, Future researchers can also confirm these results by longitudinal study, and for empirical data, longitudinal study frameworks are deemed more authentic (Li et al., 2017). Secondly, this research used a quantitative method in order to empirically test theoretical model in studied context, future studies can focus on qualitative method, and this design provides more in-depth and detailed explanation of organizational justice and knowledge sharing behavior association. In addition, future studies can investigate the impact of organization justice with two more dimensions (temporal justice and spatial justice) on knowledge sharing behavior and organization performance in the studied context or other context. Finally, present research collected data from the employees of service sector in Lahore, Pakistan, future studies can be collected data from other cities of Pakistan like Multan, Islamabad, and Karachi in order to generalize the findings of research model in the studied context or manufacturing sector, or energy sector. Indeed, it is need to be studied organizations justice, knowledge sharing behavior and organization performance in cross cultural settings like Pakistan-China, Pakistan-Bangladesh in the studied context.

References

- Adams, J.S. (1963). Towards an understanding of inequity. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(5), 422.

- Adams, J.S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2(C), 267-299.

- Adams, J.S., & Freedman, S. (1976). Equity theory revisited: Toward a general theory of social

- interaction. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 9(1), 421-436.

- Akram, T., Lei, S., Haider, M.J., Hussain, S.T., & Puig, L.C.M. (2017). The effect of organizational justice on knowledge sharing: Empirical evidence from the Chines telecommunications sector. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 2(3), 134-145.

- Allen, D.G., & Shanock, L.R. (2013). Perceived organizational support and embeddedness as key mechanisms connecting socialization tactics to commitment and turnover among new employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(3), 350-369.

- Allen, N.J., & Meyer, J.P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1-18.

- Anand, N., Gardner, H.K., & Morris, T. (2007). Knowledge-based innovation: Emergence and embedding of new practice areas in management consulting firms. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 406-428.

- Bagozzi, R.P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74-94.

- Barroso, C., Carrión, G.C., & Roldán, J.L. (2010). Applying maximum likelihood and PLS on different sample sizes: Studies on SERVQUAL model and employee behavior model. In Handbook of partial least squares. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Bartol, K.M., Liu, W., Zeng, X., & Wu, K. (2009). Social exchange and knowledge sharing among knowledge workers: The moderating role of perceived job security. Management and Organization Review, 5(2), 223-240.

- Bies, R.J. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. Research on Negotiation in Organizations, 1(1), 43-55.

- Byrne, Z.S., & Cropanzano, R. (2001). The history of organizational justice: The founders speak. Justice in the Workplace: From Theory to Practice, 2(1), 3-26.

- Castaneda, D.I., Ríos, M.F., & Durán, W.F. (2016). Determinants of knowledge-sharing intention and knowledge-sharing behavior in a public organization. Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal, 8(2), 372-386.

- Chen, S.Y., Wu, W.C., Chang, C.S., Lin, C.T., Kung, J.Y., Weng, H.C., Lin, Y.T., & Lee, S.I.(2015). Organizational justice, trust, and identification and their effects on organizational commitment in hospital nursing staff. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 363.

- Chin, W.W., & Gopal, A. (1995). Adoption intention in GSS: relative importance of beliefs. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 26(2–3), 42-64.

- Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta- analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(2), 278-321.

- Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: a construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386.

- Colquitt, J.A., Wesson, M.J., Porter, C.O.L.H., Conlon, D.E., & Ng, K.Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425–445.

- Cropanzano, R., Bowen, D.E., & Gilliland, S.W. (2007). The management of organizational justice executive overview. Academy of Management Perspectives, 10(2), 34–48.

- Cropanzano, R., Byrne, Z.S., Bobocel, D.R., & Rupp, D.E. (2001). Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(2), 164-209.

- Cugueró-Escofet, N., Ficapal-Cusí, P., & Torrent-Sellens, J. (2019). Sustainable human resource management: How to create a knowledge sharing behavior through organizational justice, organizational support, satisfaction and commitment. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(19), 5419.

- Dillon, W.R., & Goldstein, M. (1984). Multivariate analysis: Methods and applications. New York: Wiley.

- Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P.D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 42.

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500.

- Erdogan, B., & Enders, J. (2007). Support from the top: Supervisors' perceived organizational support as a moderator of leader-member exchange to satisfaction and performance relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 321.

- Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., & Wang, H. (2010). Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications. Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London, New York: Springer.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175-191.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M.C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 7.

- Gold, A.H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A.H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185-214.

- Greenberg, J. (1999). Managing behavior in organizations. 2nd edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Hair Jr, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

- Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Babin, B.J., & Black, W.C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (Vol. 7). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing theory and Practice, 19(2), 139-152.

- Hameed, Z., Khan, I.U., Sheikh, Z., Islam, T., Rasheed, M.I., & Naeem, R.M. (2019). Organizational justice and knowledge sharing behavior: The role of psychological ownership and perceived organizational support. Personnel Review, 48(3), 748-773.

- Han, T.S., Chiang, H.H., & Chang, A. (2010). Employee participation in decision making, psychological ownership and knowledge sharing: Mediating role of organizational commitment in Taiwanese high-tech organizations. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(12), 2218-2233.

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P.A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135.

- Ibragimova, B.D. Ryan, S.C. Windsor, J., & Prybutok, R.V. (2012). Understanding the Antecedentsof Knowledge Sharing: An Organizational Justice Perspective. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 15(3), 183-205.

- Imamoglu, S.Z., Ince, H., Turkcan, H., & Atakay, B. (2019). The Effect of Organizational Justice and Organizational Commitment on Knowledge Sharing and Firm Performance. Procedia Computer Science, 158(2), 899-906.

- Iqbal, Q., & Ahmad, B. (2016). Organizational justice, trust and organizational commitment in banking sector of Pakistan. J. Appl. Econ. Bus, 4(1), 26-43.

- Jaros, S. (2007). Meyer and Allen model of organizational commitment: Measurement issues. The Icfai Journal of Organizational Behavior, 6(4), 7-25.

- King, W.R., & Marks Jr, P.V. (2008). Motivating knowledge sharing through a knowledge management system. Omega, 36(1), 131-146.

- Lee, J.H., Kim, Y.G., & Kim, M.Y. (2006). Effects of managerial drivers and climate maturity on knowledge-management performance: Empirical validation. Information Resources Management Journal (IRMJ), 19(3), 48-60.

- Li, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, S., & Zhou, M. (2017). A multilevel analysis of the role of interactional justice in promoting knowledge-sharing behavior: The mediated role of organizational commitment. Industrial Marketing Management, 62(5), 226-233.

- Liao, Q.Q., Qin, Y.J., & Zhang, X. (2011). Relationship between psychological knowledge ownership and knowledge sharing: Adjustment for organizational fairness. Proceeding of the 8th International Conference on Innovation and Management, 916-920.

- Lin, C.P. (2007a). To share or not to share: Modeling tacit knowledge sharing, its mediators and antecedents. Journal of business ethics, 70(4), 411-428.

- Lin, H.F. (2007b). Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on employee knowledge sharing intentions. Journal of Information Science, 33(2), 135-149.

- Malhotra, N. (2010). Marketing research: An applied orientation. Boston: Pearson.

- Mcpherson, M. (2004). e-Society 2004: Vol. II (Issue July).

- Meyer, J.P., & Herscovitch, L. (2001). Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Human Resource Management Review, 11(3), 299-326.

- Mowday, R.T., Steers, R.M., & Porter, L.W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14(2), 224-247.

- Neneh, B.N. (2019). From entrepreneurial alertness to entrepreneurial behavior: The role of trait competitiveness and proactive personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 138(6), 273-279.

- Niehoff, B.P., & Moorman, R.H. (1993). Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 527-556.

- Notz, W.W., & Starke, F.A. (1987). Arbitration and distributive justice: Equity or equality? Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(3), 359.

- Nowakowski, J.M., & Conlon, D.E. (2005). Organizational justice: Looking back, looking forward. International Journal of Conflict Management, 16(1), 4.

- Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric Theory: 2d Ed. McGraw-Hill.

- Ponnu, C.H., & Chuah, C.C. (2010). Organizational commitment, organizational justice and employee turnover in Malaysia. African Journal of Business Management, 4(13), 2676-2692.

- Porter, L.W., Steers, R.M., Mowday, R.T., & Boulian, P.V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(5), 603.

- Rahman, A., Shahzad, N., Mustafa, K., Khan, M.F., & Qurashi, F. (2016). Effects of organizational justice on organizational commitment. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(3S).

- Ringle, C.M., Wende, S., & Will, S. (2005). SmartPLS 2.0 (M3) Beta.

- Robinson, J.P., Shaver, P.R., & Wrightsman, L.S. (1991). Criteria for scale selection and evaluation. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes, 1(3), 1–16.

- Roldán, J.L., & Sánchez-Franco, M.J. (2012). Variance-based structural equation modeling: Guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems (pp. 193–221). IGI Global.

- Roscoe, J.T. (1975). Fundamental research statistics for the behavioral sciences [by] John T. Roscoe.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons.

- Silva, M. R., & Caetano, A. (2014). Organizational justice: what changes, what remains the same? Journal of Organizational Change Management, 27(1), 23-40.

- Staley, A.B., Dastoor, B., Magner, N.R., & Stolp, C. (2003). The contribution of organizational justice in budget decision-making to federal managers’ organizational commitment. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 15(4), 505-524.

- Svetlik, I., Stavrou?Costea, E., & Lin, H.F. (2007). Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability: an empirical study. International Journal of Manpower, 28(3), 315-332.

- Tamta, V., & Rao, M.K. (2017). Linking emotional intelligence to knowledge sharing behaviour: Organizational justice and work engagement as mediators. Global Business Review, 18(6), 1580–1596.

- Tea Moon, K. (2015). The effects of organizational justice on the knowledge sharing and utilization in hotel firms. Journal of Tourism Research, 40(4), 41-59.

- Thibaut, J.W., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Van Den Hooff, B., & De Ridder, J. A. (2004). Knowledge sharing in context: the influence of organizational commitment, communication climate and CMC use on knowledge sharing. Journal of knowledge management, 8(6), 117-130.

- Walster, E., Berscheid, E., & Walster, G.W. (1976). New directions in equity research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 9(6), 1-42.

- Wang, S., & Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 20(2), 115-131.