Research Article: 2017 Vol: 16 Issue: 2

Investment Escalation in Foreign Subsidiaries: Expatriate Managers' Career Concern and Negative Framing

Sungjin J Hong, Yeungnam University

Keywords

Investment Escalation, Incentive Structure, Negative Framing, MNC.

Introduction

What factors compel foreign subsidiary expatriate managers to continue investing in projects showing pessimistic economic prospects? Is that escalation tendency mainly attributed to the cognitive ability of individuals or can it also be attributed to incentive structures of individuals? Will the individual-level cultural values of decision makers affect the strength of investment escalation intention in a given situation? Efficient resources allocation decisions are essential for the success of a multinational corporation (MNC), which is under stiff global competition (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989). From the standpoint of an MNC’s headquarters (HQ), investment projects in a certain host country are a part of the MNC’s investments portfolio (Hitt, Hoskisson & Kim, 1997; O’Donnell, 2000). Thus, when the previous investments ultimately turn out to be sunk costs, an MNC should terminate further investments on the focal previous investment projects according to economic rationality (Dixit & Pindyck, 1994).

However, previous studies reveal that this economic rationality criterion does not always hold in actual situations (Arkes & Blumer, 1985; Bazerman, 1984; Garland, 1990; Schaubroeck & Davis, 1994; Staw & Ross, 1978). In many cases, decision makers tend to keep committing resources to a series of seemingly unprofitable investments. The existing literature calls the phenomenon “escalation of commitment to a failing course of action” (Brockner, 1992; Staw, 1981).

This escalation of commitment to unprofitable investment projects may particularly matter in the MNC context for the following reasons. First, foreign subsidiaries of an MNC are geographically and culturally more distant from the HQ than are domestic subsidiaries (Gong, 2003). These cultural and geographic distances incur additional costs that might be smaller in domestic operations. One of the typical types of costs incurred by institutional distances is agency cost (Eisenhardt, 1989; Jensen & Meckling, 1976). In order to reduce agency costs in foreign subsidiaries, the HQ tends to rely on managers expatriated from the home country (Gong, 2003). However, for various reasons, expatriate managers themselves may behave opportunistically as agents (Yan, Zhu & Hall, 2002), in which case, the parent firm (i.e., HQ in home country) of foreign subsidiaries will not be able to effectively monitor opportunistic behaviours of expatriate managers, such as additional investment decisions on unprofitable projects that have already incurred sunk costs.

The escalation of commitment may be particularly important for foreign subsidiaries in an MNC because expatriate managers, even when they are psychologically loyal to the parent firm, are exposed to cognitive biases that impede accurate project evaluations. One of the critical challenges that foreign subsidiary expatriates face is not about what to do in one-time decision making, but about “the fate of an entire course of action” (Staw, 1981). The ultimate outcome of a series of prior investments is often realized throughout the long-term investment horizon (Staw & Ross, 1978). This sequential nature of investments in a host country can make expatriates perceive their previous investment decisions not as a failing course of action. In addition, even if the expatriates perceive their previous investment decisions as unprofitable, they might perceive additional investment decisions as loss recovering commitments (Davis & Bobko, 1986). In such a situation, decision framing significantly affects the risk-taking propensity of the focal decision maker’s investment decisions.

Except for a few studies (Harrison & Harrell, 1993; Sharp & Salter, 1997), the existing literature has understudied the effects of incentive structure and framing effect on investment escalation. This paper therefore aims to contribute to the literature by proposing four propositions that examine the effects of incentive structures and framings. In doing so, this paper provides theoretical and managerial implications about the motivational and cognitive aspects of escalation of commitment in the MNC subsidiary context. In addition, this paper can contribute to the literature by explicitly examining the moderating roles of individual-level cultural values, which are critical factors that have not received much attention in previous studies, due to the dominance of national cultural effects in the existing cross-cultural management literature.

Theory and Propositions

The escalation of commitment to a failing course of action refers to “the tendency for decision makers to persist with” failing resource commitments in terms of economic efficiency (Brockner, 1992). The existing literature has explained the causes of escalation in terms of psychological, social and organizational determinants (Staw, 1997). Compared to the “lack of ability” aspect in evaluating project economics, one of the unfilled research gaps is the “motivation” aspect of escalation. Although self-justification theory provides a solid rationale for why individuals need to justify their previously committed decisions (Staw, 1997), this justification need has mainly been treated as a psychological determinant rather than as an opportunistic behaviour by individual organizational members as agents (Staw, 1997).

Incentive Structure in Expatriate Career Path

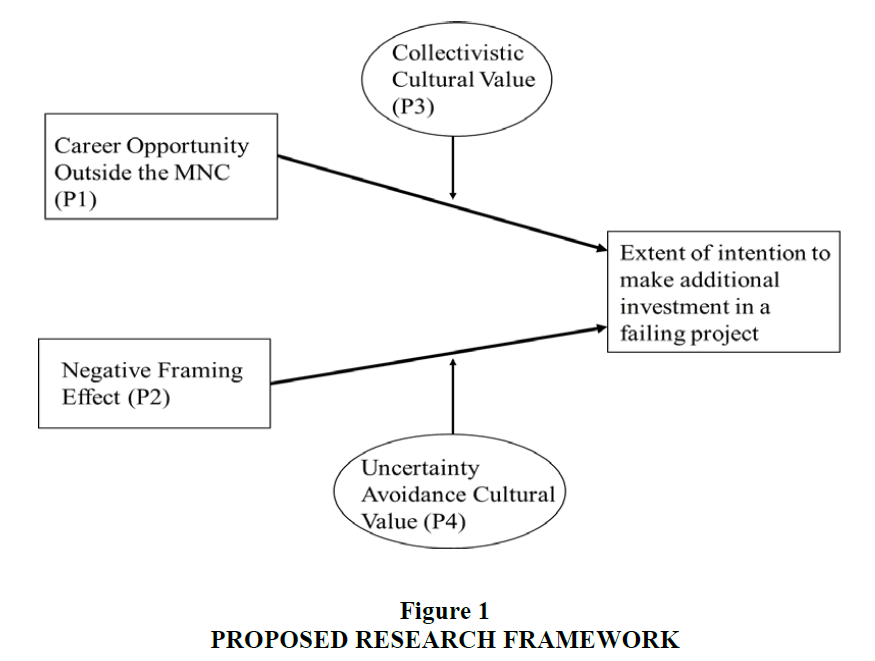

Strategic human resource management literature implicitly assumes that expatriates can protect the best interest of the parent firm from the agency costs incurred by locally hired staffs in foreign subsidiaries (Gong, 2003). However, this may not be always the case. Expatriate managers themselves may possibly behave opportunistically, when the pre-conditions of agency situations are met. Proposed research framework explained in Figure 1.

Agency theory explanations on escalation of commitment point out that both the misalignment of interests and the information asymmetry between principals and agents are pre-conditions of ‘adverse selection’ situations in foreign subsidiaries (Harrison & Harrell, 1993; Kirby & Davis, 1998). Within an MNC context, the parent firm can be a principal and foreign subsidiary managers can be agents of the parent firm.

First, information asymmetry needs to be present in order for agents to behave opportunistically. In other words, if the principal can also know that the project is failing, it is “in the best interests of the agent to discontinue a failing project” (Harrison & Harrell, 1993). Therefore, effective monitoring of foreign subsidiary managers by the parent firm could effectively safeguard escalation agency hazards. However, as previous studies (Gong, 2003; O’Donnell, 2000) point out, the cultural and geographic distance between the parent firm and the foreign subsidiary hinders the effective monitoring by the principal. That is, subsidiary managers could access private information to assist in evaluating the eventual fate of previously committed investments (Sharp & Salter, 1997). In this sense, the monitoring effect suggested by Kirby & Davis (1998) will be weak in the foreign subsidiary context.

Second, interest misalignment is necessary in order for agents to behave opportunistically. (Yan et al., 2002) illustrate how the long-term career horizon of expatriate managers can lead to goal conflicts between the principal and the agent. According to (Yan et al., 2002), regardless of the nature of the employment contract, when the principal and the agent have asymmetric perceptions of it, either agent opportunism or principal opportunism can arise.

Because expatriate assignments in a foreign subsidiary are host-country-specific career investments, subsidiary managers are in a vulnerable career position, in the case that the parent firm terminates subsidiary operations in the host country. Furthermore, if the parent firm intentionally misinforms, for repatriation purpose, the subsidiary manager that the expatriate assignment can increase promotion opportunities within the MNC, the subsidiary manager will perceive the MNC violated “psychological contracts” (Yan et al., 2002). In the case that the subsidiary manager’s career opportunities are constrained by his/her international assignments, so as to fully leverage the accumulated country-specific experience, subsidiary managers tend to search for better career opportunities whenever those opportunities are available (Yan et al., 2002).

Especially, the likelihood of opportunistic behaviour will be reinforced by the extent of career concerns within the MNC. If the focal expatriate can increase his/her status and reputation within a host country by keep the existing investment project going, the subsidiary manager will have strong personal incentives to keep escalating the commitment to the focal project. In many cases, subsidiary managers take advantage of social ties that they have built through previous investments to search for new career opportunities beyond the current tenure (Shapiro, 1987). For instance, when an expatriate has been assigned to work for an international joint venture formed with a local partner, he/she can have more opportunities to receive a job offer from the local partner firm.

Related to the impacts of the misalignment of incentives between the subsidiary manager and the parent firm, if the subsidiary manager (i.e., agent) perceives the human resources management (HRM) system of the parent firm to be unfair in terms of organizational justice, such that his/her expatriate career might not be assets for internal promotion within the MNC, the level of the agent’s organizational commitment will be significantly reduced (Johnson, Korsgaard & Sapienza, 2002). This lower level of organizational commitment will increase the incentive for opportunistic behaviour whenever it is necessary. The rationale behind this “agent opportunism” prediction is that the escalation of commitment tendency is supposed to be associated with the agent’s concerns on career reputations.

In regards to the relationship between individual career reputation and escalation of commitment, foreign expatriates are likely to be concerned about two types of career reputation. In terms of within-MNC career path, expatriates tend to be more concerned about their reputations as a ‘responsible manager.’ Expatriates have incentives to maintain their reputations as accountable agents within the MNC, especially before they become involved in failing investments in host countries. However, once they commit to failing investments, another type of career reputation becomes more important. In addition to within-MNC career path, expatriates may have to be concerned about within-host-country career path, because their expatriate careers can be viewed as country-specific career investments. After committing to seemingly failing investments, expatriates have incentives to maintain their reputation as a ‘successful’ or ‘not- failing’ manager. If expatriates decide to terminate the investment that they previously instigated, they will face the risk of a damaged reputation due to the responsibility of failed investments. On the other hand, additional investment decisions could promote the decision maker’s influence and status towards relevant business stakeholders (Guler, 2007).

Therefore, when an expatriate gains an external career opportunity generated by his/her local experience in the host country in general and by his/her previous investment decisions in particular, the focal expatriate is more likely to commit investment escalation, which becomes agency costs from the parent firm’s perspective. The above discussion leads to the following proposition.

P1 External career opportunities will be positively related to the strength of intention to make additional investments by the expatriate responsible for previous failing investment decisions.

Impact of Decision Framing

If a decision maker perceives previous investments as sunk costs, which are irreversible, there is no economic reason for him/her to be locked into previous investment decisions. Contrary to the prediction based on economic rationality, however, individuals often regard sunk costs as psychologically recoverable, due to their information processing errors (Arkes & Blumer, 1985). In many cases, previous losses continue to influence subsequent investment decisions (Staw & Ross, 1995). Furthermore, a decision maker’s perception of the possible outcomes may influence subsequent investment decisions (Whyte, 1993).

In particular, prospect theory (Bazerman, 1984; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) proposes decision framing as a possible reason why decision makers commit additional resources “without favourable results in order to justify the previous commitment” (Bazerman, 1984). According to Kahneman & Tversky (1979), decision makers often tend to be risk seekers especially when the decision context is depicted as a loss situation, because the decisions are made after referent information has been filtered through the decision frame. In the context of foreign subsidiary expatriates, if the subsequent investment decisions are framed as loss situations, this negative framing effect will make expatriates less risk averse in subsequent investment decisions.

For instance, Sharp & Salter (1997) show that managers originating from a culture placing high value on ‘saving face’ are likely to escalate commitments in existing failing investments. Several studies adopt different interpretations about the nature of sunk costs incurred by previous investments, from the interpretation suggested by the economics perspective. Moon (2001) points out that, in general, decision makers are psychologically committed to completing already-initiated tasks. Although escalation of commitment increases the level of sunk costs, if a decision maker perceives the incremental level of completion to be higher than the incremental level of sunk costs, he/she will have higher utility by escalating commitment (Moon, 2001).

In particular, according to prospect theory, the expected value function exhibits a convex shape when the decision situation is placed at the loss side (Schaubroeck & Davis, 1994). Similarly, the order preferences among choices of behaviour may depend upon the framing of the alternative choices (Bazerman, 1984). If the reference point for the subsequent choice is a given loss situation, which is dependent on previous choices, a decision maker might form relatively less risk adverse perceptions on the prospects of the subsequent choice. The above discussion leads to the following proposition concerning the relationships between decision framing and intention to make additional investments.

P2 The loss situation framing on the additional investments will be positively related to the strength of intention to make additional investments by the expatriate responsible for previous failing investment decisions.

Moderating Roles of Individual Cultural Values

A few previous studies (Greer & Stephens, 2001; Salter & Sharp, 1997) have examined whether decision makers’ cultural values affect the likelihood of investment escalation, according to their countries of origin. This national culture approach has some limitations, because cultural values are meaningful not only at the societal level but also at the individual level (Farh, Hackett & Liang, 2007). For example, in the literature review, Kirkman, Lowe and Gibson (2006) found many studies in which cultural values were examined at the individual level (Clugston, Howell & Dorfman, 2000; Kirkman & Shapiro, 2001). Consideration of individual-level cultural values is particularly relevant in this study, which examines the effects of individual-level agency costs and individual responses on decision framings.

It is plausible that decision makers with individualistic cultural values might exploit more adverse selection opportunities when available. Hofstede (1980) defines individualism as “a social framework in which people are supposed to take care of themselves and of their immediate family only.” In the same vein, Hofstede defines collectivism as “a social framework in which people distinguish between in-groups and out-groups and they expect their in-group to look after them and feel absolute loyalty to it (Hofstede, 1980; Kirkman et al., 2006).” Expatriates who have collectivistic cultural values are likely to face institutional pressures that reach to psychological employment contracts rather than transactional contracts (Yan et al., 2002). In contrast, expatriates with individualistic cultural values feel minimal moral obligations to each other (Johnson & Droege, 2004). Goal alignment between employee and employer does not necessarily depend on support and sanction mechanisms that are based on socially embedded relationships. Therefore, from the standpoint of expatriate managers with collectivistic cultural values, individual financial incentives might not always lead to ‘adverse selection’ situations (Johnson & Droege, 2004). It is mainly because subsidiary managers can take advantage of the social network in which they are embedded and be constrained by the informal sanction mechanisms in which they are bonded (Shapiro, 1987), beyond the benefits and costs determined by financial and career opportunities.

Relationship emphasis in collectivistic cultural values also can mitigate the likelihood of escalation decisions based upon self-justifying motivation. Since the favourable relationships and long-term ties are reciprocal in nature, subsidiary managers who are responsible for failing previous investments can perceive less severe criticisms and performance evaluations. The above discussion leads to the following proposition regarding the moderating effect of individualistic cultural values.

P3 When external career opportunities arise; expatriate managers with collectivistic cultural values will show a weaker intention to make additional investments than will decision makers with individualistic cultural values.

Another cultural dimension that affects the likelihood of escalation decisions is uncertainty avoidance. Uncertainty avoidance is defined as the extent to which “a society feels threatened by uncertain and ambiguous situations and tries to avoid these situations by providing greater career stability, establishing more formal rules and believing in absolute truths and the attainment of expertise (Hofstede, 1980; Kirkman et al., 2006).” A decision maker with high uncertainty avoidance is likely to minimize ambiguities created by sequential uncertain investments and ambiguities created by the decision framings. In order to reduce uncertainties, subsidiary managers with high uncertainty avoidance are likely to stick to the existing organizational routines (March & Simon, 1958). If the parent firm organizational routines follow conservative decision making criteria, the subsidiary managers with high uncertainty avoidance will tend to lean on conservative decision making attitudes, even if the decision situations are framed as loss situations. The psychological commitment to failing investments is closely related to low-risk perceptions on recovering resource commitments. However, on average, the expatriate managers will tend to perceive the sunk costs nature of previous investments more saliently. Thus, expatriate managers with high uncertainty avoidance cultural values will be less psychologically entrenched by negative framing effects, compared to expatriate managers with low uncertainty avoidance cultural values. The above discussion leads to the following proposition regarding the moderating effect of uncertainty avoidance cultural values.

P4 When a loss situation arises; expatriate managers with higher uncertainty avoidance cultural values will show a weaker intention to make additional investments than will expatriate managers with lower uncertainty avoidance cultural values.

Discussion

Contributions and Limitations

Unlike previous studies that focus on the potential agency costs incurred by locally hired managers, this paper seeks to provide a theoretical explanation of how expatriation assignments to foreign subsidiaries can incur potential agency costs. The agency costs potentially incurred by expatriate managers may arise from the lack of interest alignment between the parent firm (principal) and subsidiaries (agents) in terms of career incentive structure (Kostova, Nell & Hoenen, 2016).

Because expatriate managers, as agents, may perceive a high level of uncertainty about their repatriation career, they will be incentivized to make additional investments on failing projects in case the investments expand career opportunities outside the MNC. In other words, a unique incentive structure regarding expatriates career path would induce them to behave opportunistically when the external career opportunities are gained by their escalation of commitments.

In addition, this paper proposes that individual-level collectivistic cultural values and uncertainty avoidance cultural values interact with agency conditions and negative framing conditions. These moderating relationships can shed new light on the research into the effects of cultural values on expatriate managers’ investment escalation behaviours in the sense that previous studies tend to assume that agents’ behaviours are strictly embedded in a host country’s national cultural values and institutions (Kostova et al., 2016).

Of course, the potential contributions of this paper are constrained by several limitations that should be considered in future studies. First, even though we can empirically test the propositions by using various investment decisions scenarios utilized in previous studies (Salter & Sharp, 2001), the critical challenge for future research remains of how to control for the cognitive biases that may arise from the lack of international investment experience of experimental participants. Even though recruiting experienced MBA students has been considered an acceptable method for experimental data collection in previous studies (Harrison & Harrell, 1993), such study methodology will restrict the study generalizability.

Second, without considering the level of the focal manager’s organizational commitment and perceived fairness, we cannot effectively isolate the net effects of agency conditions provided by external career opportunity. By using the items suggested by (Johnson et al., 2002), future studies may be able to control for these factors.

Third, future studies should manipulate the information asymmetry between the parent firm and the subsidiary for accurate measurement of agency conditions because the expatriate agency argument in this paper is based on the information asymmetry assumption. Thus, future studies should manipulate the experimental conditions such as significant institutional distance between home and the focal host country (Tihanyi, Griffith & Russell, 2005).

Lastly, without effective manipulation of personal responsibility, it is difficult to measure the net effect of agency conditions. For example, manipulation checks about the effectiveness of personal responsibility and monitoring of the investment process can be conducted in future studies by using the item suggested by (Kirby & Davis, 1998).

Suggestions for Future Research on Agency Problems in MNCs

This paper intends to facilitate the conversation on potential agency costs incurred by expatriate managers in MNC subsidiaries. Future research should look into other theoretical perspectives that provide alternative explanations on agency problems within MNCs. First, institutional theory (Kostova, Roth & Dacin, 2008) implicitly argues that subsidiary managers face dual institutional pressures between isomorphic management practices required by local stakeholders and strategic mandates assigned by their headquarters. Considering this “institutional duality” (Kostova & Roth, 2002), individual agents’ economic incentives, such as external career opportunities, may play less important roles in determining the extent of agency costs incurred by expatriate managers especially when internal institutional pressures are greater than local isomorphic pressures. Future research should examine the relative importance of social/institutional pressures vis-à-vis individual economic incentives in determining the extent of agency costs in MNCs. In particular, some subsidiaries that serve as a regional headquarter may face greater level of dual institutional pressures than other subsidiaries do (Conroy, Collings & Clancy, 2016). In this regard, future research should empirically examine agency costs in regional headquarters.

Second, related to knowledge based view of MNC (Kogut & Zander, 1993), this paper did not explicitly discuss the capability aspect of expatriate managers. Not only expatriate managers can play a critical role in transferring knowledge to the focal subsidiary (Chang, Gong & Peng, 2012), but also they can help reverse knowledge transfer from the subsidiary to the headquarter based on local knowledge acquired in the host country (Fang, Jiang, Makino & Beamish, 2010). Future research should examine whether capability benefits of using expatriate mangers in facilitating conventional and reverse knowledge transfer between the headquarter and subsidiaries exceed agency costs incurred by expatriate managers. In addition, future research should examine whether net agency costs exceeding the benefits of using expatriate managers may be smaller than net agency costs of using locally hired managers.

Third, in order to apply proposed research framework in this paper to broader discussion, future research should consider different types of MNC strategies. For instance, subsidiary managers with “global” strategy mandates may face different agency situations from those managers with “multi-domestic” strategy mandates (Birkinshaw & Morrison, 1995) because multi-domestic strategy may allow greater discretion in case of appropriate monitoring mechanisms, whereas it encourages subsidiary initiative and knowledge creation (Birkinshaw & Hood, 1998; Kostova et al., 2016). At the same time, in case of significant institutional distance between home and host countries, global strategy may impose repatriation career concerns (Malnight, 1995). The proposed framework in this paper implicitly assumes MNCs with global strategic mandates. Future research should examine whether the “repatriation concern” effect exceed the “monitoring concern” effect for both global and multi-domestic strategies in determining the extent of agency costs in MNC subsidiaries (Kim, Prescott & Kim, 2005).

In closing, this paper provides a departure point for future conversation on potential agency costs incurred by managers expatriated to subsidiaries using their intent to continue failing investments as a unique context. This effort can extend our attention beyond traditional discussion on agency costs incurred by locally hired subsidiary managers.

EndNote

This work was supported by 2016 Yeungnam University Research Grant. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Academy of International Business conference held in Rio de Janeiro.

References

- Arkes, H. & Blumer, C. (1985). The psychology of sunk costs. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 35, 124-140.

- Bartlett, C. & Ghoshal, S. (1989). Managing across borders: The transnational solution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Bazerman, M.H. (1984). The relevance of Kahneman and Tversky’s concept of framing to organizational behaviour. Journal of Management, 10, 333-343.

- Birkinshaw, J. & Hood, N. (1998). Multinational subsidiary evolution: Capability and charter change in foreign-owned subsidiary companies. Academy of Management Review, 23, 773-795.

- Birkinshaw, J. & Morrison, A.J. (1995). Configurations of strategy and structure in subsidiaries of multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 26, 729-753.

- Brockner, J. (1992). The escalation of commitment to a failing course of action: Toward theoretical progress. Academy of Management Review, 17, 39-61.

- Chang, Y.Y., Gong, Y. & Peng, M.W. (2012). Expatriate knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity and subsidiary performance. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 927-948.

- Clugston, M., Howell, J.P. & Dorfman, P.W. (2000). Does cultural socialization predict multiple bases and foci of commitment? Journal of Management, 26, 5-30.

- Conroy, K.M, Colling, D.G. & Clancy, J. (2016). Managing a dual agency role in regional headquarters. Paper presented at European International Business Academy, Vienna, Austria.

- Davis, M.A. & Bobko, P. (1986). Contextual effects on escalation processes in public sector decision making. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 37, 121-138.

- Dixit, A. & Pindyck, R. (1994). Investment under uncertainty. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14, 57-74.

- Fang, Y., Jiang, G.L.F., Makino, S. & Beamish, P.W. (2010). Multinational firm knowledge, use of expatriates, and foreign subsidiary performance. Journal of Management Studies, 47, 27-54.

- Farh, J.L., Hackett, R.D. & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support-employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 715-729.

- Garland, H. (1990). Throwing good money after bad: The effect of sunk costs on the decision to escalate commitment of an on-going project. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 728-731.

- Gong, Y. (2003). Subsidiary staffing in multinational enterprises: Agency, resources and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 728-739.

- Greer, C.R. & Stephens, G.K. (2001). Escalation of commitment: A comparison of differences between Mexican and U.S. decision-makers. Journal of Management, 27, 51-78.

- Guler, I. (2007). Throwing good money after bad? Political and institutional influences on sequential decision making in the venture capital industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52, 248-285.

- Harrison, P.D. & Harrell, A. (1993). Impact of ‘adverse selection’ on managers’ project evaluation decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 635-643.

- Hitt, M.A., Hoskisson, R.E. & Kim, H. (1997). International diversification: Effects on innovation and firm performance in product-diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 767-798.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9, 42-63.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions and Organizations across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Jensen, M. & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305-360.

- Johnson, N.B. & Droege, S. (2004). Reflections on the generalization of agency theory: Cross-cultural considerations. Human Resource Management Review, 14, 325-335.

- Johnson, J.P., Korsgaard, M.A. & Sapienza, H.J. (2002). Perceived fairness, decision control and commitment in international joint venture management teams. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 1141-1160.

- Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263-291.

- Kim, B., Prescott, J.E. & Kim, S.M. (2005). Differentiated governance of foreign subsidiaries in transnational corporations: An agency theory perspective. Journal of International Management, 11, 43-66.

- Kirby, S.L. & Davis, M.A. (1998). Study of escalating commitment in principal-agent relationships: Effects of monitoring and personal responsibility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 206-217.

- Kirkman, B.L., Lowe, K.B. & Gibson, C.B. (2006). A quarter century of culture’s consequences: A review of empirical research incorporating Hofstede’s cultural values framework. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 285-320.

- Kirkman, B.L. & Shapiro, D.L. (2001). The impact of team members’ cultural values on productivity, cooperation and empowerment in self-managing work teams. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 597-617.

- Kogut, B. & Zander, U. (1993). Knowledge of the firm and evolutionary theory of the multinational corporation. Journal of International Business Studies, 24, 625-645.

- Kostova, T. & Roth, K. (2002). Adoption of an organizational practice by subsidiaries of multinational corporations: Institutional and relational effects. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 215-233.

- Kostova, T., Roth, K. & Dacin, M.T. (2008). Institutional theory in the study of multinational corporations: A critique and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 33, 994-1006.

- Malnight, T. (1995). Globalization of an ethnocentric firm: An evolutionary perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 16, 119-141.

- Moon, H. (2001). Looking forward and looking back: Integrating completion and sunk-cost effects within an escalation-of-commitment progress decision. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 104-113.

- O’Donnell, S.W. (2000). Managing foreign subsidiaries: Agents of headquarters or an interdependent network? Strategic Management Journal, 21, 525-548.

- Salter, S.B. & Sharp, D.J. (2001). Agency effects and escalation of commitment: Do small national culture differences matter? International Journal of Accounting, 36, 33-45.

- Schaubroeck, J. & Davis, E. (1994). Prospect theory predictions when escalation is not the only chance to recover sunk costs. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 57, 59-82.

- Schwartz, S.H. (1994). Cultural dimensions of values: Towards an understanding of national differences. In U. Kim, H.C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S.C. Choi and G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and Collectivism: Theoretical and Methodological Issues (pp. 85-119). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Shapiro, S. (1987). The social control of impersonal trust. American Journal of Sociology, 93, 623-658.

- Sharp, D.J. & Salter, S.B. (1997). Project escalation and sunk costs: A test of the international generalizability of agency and prospect theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 28, 101-121.

- Staw, B.M. (1981). The escalation of commitment to a course of action. Academy of Management Review, 6, 577-587.

- Staw, B.M. (1997). The escalation of commitment: An update and appraisal. In Z. Shapira (Eds.), Organizational Decision Making, Cambridge. UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Staw, B.M. & Ross, J. (1978). Commitment to a policy decision: A multi-theoretical perspective. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 40-64.

- Staw, B.M. & Ross, J. (1995). Understanding behavior in escalation situations. In B.M. Staw (Eds.), Psychological Dimensions of Organizational Behaviour, 228-236.

- Tihanyi, L., Griffith, D.A. & Russell, C.J. (2005). The effect of cultural distance on entry mode choice, international diversification and MNE performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 36, 270-283.

- Whyte, G. (1993). Escalation of commitment in individual and group decision-making: A prospect theory approach. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 54, 430-455.

- Yan, A., Zhu, G. & Hall, D.T. (2002). International assignments for career building: A model of agency relationships and psychological contracts. Academy of Management Review, 27, 373-391.