Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Local and Central Political Conflict in the Implementation of Post-Mining Policies in East Kalimantan Province, Indonesia: A Review

Eddy Iskandar, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Universitas Mulawarman

Muhammad Noor, Universitas Mulawarman

Razlini Mohd Ramli, Universiti Sains Malaysia

Budiman, Universitas Mulawarman

Azmil Mohd Tayeb dan, Universiti Sains Malaysia

Mohamad Shaharudin Samsurijan, Universiti Sains Malaysia

Abstract

Mining activity is one of the major economic contributors in Indonesia. Mining activity has increased the economy of the local people in various parts of Indonesia such as Kalimantan, Sumatra, and Papua. The context of this study had taken a case of a political conflict in an implementation of post-coal mining policies in East Kalimantan Province. This study used the exploratory research method. This research found that government had become very reliant on mining activity and this had led to social, economic and environmental impacts. Thus, people realized that mining activity did not increase their welfare but in contrary caused negative impacts, hence rose political conflict between the government and local people. It can be analyzed that the factors that cause political conflict are due to structural problems, namely regulatory policies, in this case, Government Regulation No. 78/2010 concerning Reclamation and Post-Mining. Political conflicts occur because of different interests or a belief that the aspirations of the parties to a conflict cannot be achieved simultaneously.

Keywords:

Post-Mining, Policy, Conflict, Politic

Introduction

Indonesia is a country rich with natural resources such as oil, gas, coal, copper, nickel and etc (Kuo, 2012). Among various large scale mining in Indonesia, one of it is coal mining which widely spread in various regions in Indonesia such as Kalimantan and Sumatra (Abood et al., 2015; Sunderlin, 1999). In East Kalimantan Province with an area approximately 130,000 square kilometres wide contains rich natural resources, namely coal, minerals, gas and oil (MacKinnon et al., 1996).

Coal is one of the largest sources of energy in the world, where its use continues to increase, both lignite and hard coal, hence its supply will be adjusted accordingly following to the demand for world coal consumption where its supply is estimated to exist up until 2100 and it can meet the coal world demand (Thielemann et al., 2007).

In fact, the increase in coal demand has boosted the increase of coal-mining activity in several parts of the world including Indonesia, which has become the world's largest coal exporter and major supplier to coal market in Asia (Belkin et al., 2009).

According to the Geological Agency of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM), Indonesian coal production in 2017 was 461 million tons and the sources were 125 billion tons with the reserves of 26.2 billion tons. Moreover, in 2018, the coal production raised to 485 million tons and the sources to 166 billion tons with reserves to 37 billion tons. The Indonesian rich natural resources has been explored to fulfil the Indonesian people needs. The existence of coal mining has contributed a lot to the Indonesian economic development (Ginting, 2010).

East Kalimantan Province produced 83 million tons of coal with an average production of around 250 million tons per year (37 per cent of total coal reserves in Indonesia) (Baruya, 2009). Coal exploration had given a great contribution to the people of East Kalimantan Province. Currently, the East Kalimantan provincial government has granted permits for exploration of natural resources on a large scale, including coal mining activity (Ginting, 2010). as shows in Table 1.

| Table 1 Mining Permit License (Iup) in the Province of East Kalimantan |

||

|---|---|---|

| No | Cities/Districts | Number of IUP |

| 1 | Samarinda | 63 |

| 2 | Kutai Kartanegara | 625 |

| 3 | Kutai Timur | 161 |

| 4 | Kutai Barat | 244 |

| 5 | Paser | 67 |

| 6 | Penajam Paser Utara | 151 |

| 7 | Berau | 93 |

| Total | 1.404 | |

Mining is an activity to draw on natural resources, such as coal and minerals, for the country’s development and the improvement of its people standard of living. Coal mining business can bring positive impacts on increasing people’s economic level and development (Al-fatah, 2014). However, there are some negative impacts on the environment after the coal mining activities which cause damages to environmental ecosystems and led to social and political conflicts (Kuter, 2013).

The same research was also conducted by Ghose & Majee, (2000); Listiyani (2017); Nel, et al., (2003); Zhengfu, et al., (2010); Si, et al., (2010); Samsurijan, et al., (2018). coal mining activities also can cause forest ecosystem damages; pollute water, land and air; also potentially change topography and land surface conditions (land impact); produce dust and smoke which pollute air and water; produce residual water and mining waste (tailings) that contain toxic substances; also the noise from heavy machinery and mine explosions which cause landslides and health problems.

Meanwhile, the social impacts in the community included the high traffic on public roads, political conflicts in land ownership, changing in cultural values of the community, damages to the post-mining lands, damages to agricultural and plantation lands, clearing of forest areas to mining areas. In the long term, mining will be the biggest contributor to the destruction of critical land, and it is exceedingly difficult to restore the original function of this land. Pollution of soil, water and air have resulted in damages to biodiversity and road facilities (Bian et al., 2009). Furthermore, there was a decreasing of the rural community welfare because of coal mining. It was caused by the imparity between the increase growth of population and infrastructure in the economy, health, education, and transportation (Akabzaa & Darimani, 2001).

Economically, mining activity can provide great benefits by getting profit from foreign investment and employment absorption of local workers, which can increase local own-source revenue where the businessmen are subject to taxes and others. However, the economic benefits obtained are not comparable to the environmental damages caused by mining activities that are subject to exploration and exploitation (Fünfgeld, 2016).

Ironically, mining activities often caused political conflicts in local people located around the mining areas. This political conflict rose due to the effects of coal mining. Impacts from mining activity were not only causing physical damages to the environment, but it was also violating human rights and social justice; leading to injustice and poverty; and involving the labour issue (Resosudarmo et al., 2012; Samsurijan et al., 2018).

Described above situation can lead to political conflicts. Political conflict in this study was a relationship between two or more existing parties (individuals or groups), or those whose felt having different objectives. Political conflict occurs when people’s objectives are no longer in the same directions. For instance, status gap in the society, unequal welfare, inequitable access to natural resources, and unfair distribution of power which caused problems like unemployment, poverty, oppression, and crime (Resosudarmo et al., 2012).

Based on above problems elaboration, this study will examine such issues as follows, ‘How local and central political conflicts in their implementation of post-mining policies in East Kalimantan Province’; ‘To what extent the effects of local and central political conflicts in their implementation of post-mining policies in East Kalimantan Province’; and ‘How to resolve local and central political conflicts in their implementation of post-mining policies in East Kalimantan Province’. This study was carried out to achieve its objectives, namely to know local and central political conflicts in their implementation of post-mining policies in East Kalimantan Province, to analyse the effects of local and central political conflicts in their implementation of post-mining policies in East Kalimantan Province, and to provide suggestions on resolving local and central political conflicts in their implementation of post-mining policies in East Kalimantan Province.

Literature Review

Overview Concept of Conflict

Conflict is the most important element in humans, because conflict has positive functions (Coser, 1957), conflict also has become the dynamic in human history (Henry & Mark, 2003). Conflict means disagreement or contestation/dispute. It appears in a form of clash of idea or physical dispute between two different parties in opposite sides; different goals and interests; having dissimilar goals in life aspects, such as economic, socio-cultural and political (Lingard & Francis, 2006). Taulman & Robbins (2014) explained that conflict is a process of interaction that occurs due to a mismatch between two opinions (points of view) which affects the parties involved, either positive or negative impacts.

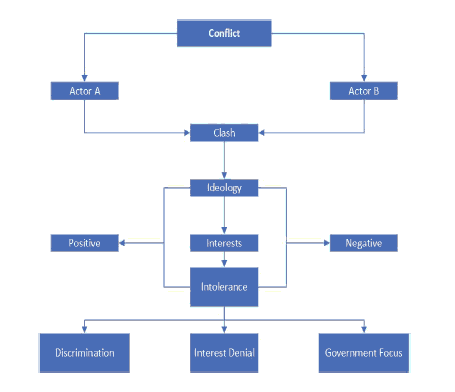

According to Jeong (2008), conflict is often related to political, ethical and psychological dimensions. In line with Bartos & Wehr (2002); Jeong (2008); Pruitt & Rubin (2004); Wolff et al., (2002) stated that conflict is disagreement and enmity in the form of physical confrontation amongst actors in struggling for value and power, scarce resources and in achieving mutual goals or needs. Conflict is not only can create a progress in the society, but it also can mature the society (Nix & Hale, 2007). as shows in Figure 1.

Figure 1: General Concept of Conflict

Source: Adapted from (Jeong, 2008; Pruitt & Rubin, 2004; Wolff et al., 2002)

Pruitt & Rubin (2004) defined conflict as a perception of different interests. Interests in this context are disagreement or dissimilarity in actual wants or goals. The importance of actualising the needs of safety from threats, needs of gaining power and a better life. Conflict of interests have various dimensions and manifestations, which can be manifested in a form of struggling for values, power and rare resources.

The Definition and Concept of Politics

Seliger (2019) stated that politics is a science that focuses on the issues of a nation, by struggling to achieve knowledge and understanding about a state and its conditions, its basic characteristics in various forms or manifestations of development. Meanwhile, Jacobson & Carson (2019) explained that politics has two meanings, namely as follows: politics as ethics; related to humans’ goals or individuals to live continuously perfectly, politics as a technique; related to the humans or individuals’ way in obtaining their goals.

Meanwhile, Heywood (2015) divided understanding about political into four assumptions; (1) politics as the art of government, the application of public control through the making and the empowering of collective decisions; (2) politics as a public relation, humans can only get a proper life through the political society; (3) politics as a component of compromise and consensus, resolving friction of interests through the process of compromising and achieving the consensus without any violence; (4) politics as a power, the ability of a person or group to influence other people or groups to comply with their will.

Various Definition and Concept of Political Conflict

A Concept Defined the Relationship of Individuals and Groups

As a political activity, political conflict is a type of interaction characterised by violations of interests, ideas, policies, programs, and personal or other policy issues which contradict each other, such as the differences of opinion, competition and conflicts between individuals, individuals with groups, groups with groups, or groups with the government (Bartos & Wehr, 2002). The driving factors for potential conflicts to be open are the needs of changing (Wehr, 2019).

Political conflicts occur due to the disparity in interests between communities and mining companies as well as the involvement of the government in policy’s conflicts made by them, the existence of inequality and the dominance of the welfare/added value of the community's economy (Serneels & Verpoorten, 2015). Political conflict is a relationship between two or more parties (individuals or groups) who have or think that they have different goals (Northcott, 2013). Political conflict is a fact of life, unavoidable and often creative (Mink, 2019). Political conflict occurs when people's goals do not align (Mehta, 2013). Disagreements and political conflicts can usually be resolved without violence and often resulted in a better situation for most of the community or all parties involved (Abuya, 2016).

A Concept of Social Conflict

Political conflict is one type of social conflicts (economic and cultural), where both have similar characteristics, the only thing that distinguishes social and political conflict is on the word “politics” which carries a certain connotation for the term “political conflict”, which related to the state or government, political or government officials, and policies (Rauf, 2001b). Political conflict is a social process in which people or groups try to fulfil their goals by opposing the rival parties with threats or violence (Earl, 2011). According to Waltkins, Conflict occurred because there were two conflicting parties and both had the potential to hinder each other (Baillien & De Witte, 2009).

The Wehr study (2019) showed conflicts between communities and the authorities that lasted for a long time and created social changes; the existing of social relationship tension between communities with the government and mining companies. These conflicts occurred because of unequal distribution and unsuccessful discussions. According to the theory of Pruitt and Rubin (2004), when every element or every institution was giving support to stability, therefore the conflict theory saw that every element had contributed to a social disintegration. Community members conflicts were informally bounded by values, norms, and general morality, hence political conflict theory assessed that the order existed in community was only caused by the existence of pressure or coercion of power from top by a group of people in power (Malone, 2012).

The Differences of Ideology

Basically, politics is always about conflicts and competition of interests (Baillien & De Witte, 2009). Conflict began with controversies that arose in various political events, this controversy was preceded by abstract and general things, then continued and were processed into a conflict (Gonzalez-Vicente, 2012). Political conflict was a result of the sharpening of differences and the severity of the conflict of interest of the opposing interests, which was caused by several existing backgrounds, namely the existence of different socio-political, economic and socio-cultural backgrounds; and the existence of dissimilar thoughts between one another (McGrew & Lewis, 2013).

A Community Collective Concept

Specifically, political conflicts can be formulated as a community members collective activity directed against public policies and its implementation, as well as the behaviours of the authorities, along with all their rules, structures, and procedures that regulated the relationships between political participants (Susan & Oyamada, 2015). Political conflict is an important barometer in seeing the dynamics of a society/community (Swyngedouw, 2009). For most people, political conflict is still considered as a form of relationship that is negative, destructive, or unproductive, even in societies that are developing towards strengthening civil society, political conflict in a society is always considered as an inseparable part of the modern society development (Draper, 2017). Political conflicts between groups in society with the state should be understood as a necessary synergy for the advancement of life of the nation and state (Tamarasari, 2002).

A Positive and Negative Concept

Political conflict values positively when the conflict can be managed wisely and prudently, in this context the political conflict is a dynamic social process and is constructive for the society social changes and does not bring violence so that political conflict can be connected as a source of change (Bercovitch, 2019). Political conflict in the context of democracy is no longer understood as a negative, bad and destructive activity, but on the contrary, conflict is a positive and dynamic activity (Friedkin, 2006). This continues with the change in the conception of conflict resolution into conflict management. First, conflict resolution refers to the termination or elimination of a conflict, thus the implication is that the conflict is something negative. Second, conflict managers provide an understanding that conflict can be positive and negative (Friedkin, 2006).

The Winning or Losing Fight

Political conflict is all kinds of conflicting or antagonistic interactions between two or more parties (Malone, 2012). These conflicts of interest differ in its intensity depending on the means used. Each wants to defend the values that have deemed them right and force the other parties to acknowledge those values both subtly and harshly (Peters et al., 2005). Society is in a static condition or rather moves in a state of balance, so according to the theory of conflict, it is the opposite. Society is always in a process of change which is characterised by the continuous conflicts between its elements (Friedkin, 2006).

The Domination of Community Groups

Galtung (2004) explained that conflict can occur when individuals or groups failed to meet their needs. Moreover, these needs were related to a non-negotiable principle needs or known as a non-negotiable principle. Furthermore, when individuals felt threatened in their survival, wellbeing, identity, and freedom, then individuals would tend to fight in fulfilling these needs. In their attempt to, individuals required belief in an effort to support their actions, can be in a form of religion, ideology, partner, and family (four basic needs).

Theories Related to Political Conflicts

There are several conflict theories pioneered by well-known thinkers and often explained in studies related to political conflict. However, this study was interested in explaining three (3) popular theories in understanding and adapting them to this study. Among of them are Karl Mark's Social Class Theory, Ralf Dahrendrof's Theory, and Pruitt and Rubin's Theory.

Karl Marx's Social Class Theory

A famous conflict theory is the conflict theory introduced by Karl Marx regarding the Theory of Social Class. With the emergence of capitalism, there was a sharp separation between those who controlled the means of production and those who only had physic or energy. The development of capitalism exacerbated contradictions between the two social categories so that eventually there was a conflict between the two classes (Marx, 2010). The exploitation carried out by the bourgeoisi (bourgeois) to the workers (proletariat) continuously would eventually raise the consciousness of the workers to rise and fight so that a big social change occured, such as the social revolution (Lane, 2019). According to Marx’s prediction (2010) that the workers won this class struggle and would create a classless and stateless society.

Marx (2010) who viewed society in general as composed of various classes in conflict; the ruling class or the owners of capital (bourgeois) and the ruled or working class (proletariat). The root of conflict between these two classes was the degree of inequality in the distribution of scarce resources in the societies in which they existed. The scarce resources that occured meaning power, capital, wealth, joy, practicality, and others. The higher the level of inequality, the higher the potential for conflict between the two (Jeong, 2008).

Karl Marx considered that the trigger for the conflict between these two classes was economic. In accordance with the condition of the society that he observed and the nature of the conflicts he concerned about during his lifetime, these scarce resources really revolved around economic issues. However, it was important to note here that both either the ruling class or the controlled class have their interest in these resources (Davis & Harveston, 2001). as shows in Table 2.

| Table 2 Causes Of Conflict From Karl Mark's Social Class Theory |

|

|---|---|

| Theory | Indicators |

| Social Class (Karl Marx) | Unevsen income distribution |

| Group awareness | |

| Cooperation awareness | |

| Class creation | |

| Widespread polarization | |

| Structural Changes | |

The Theory of Ralf Dahrendorf

Dahrendorf (1990) explained that conflict has a structural source, namely the power relations that prevailed in the structure of social organizations. In other words, conflicts between groups can be seen from the point of view of conflicts about the validity of the existing power relations. However, in the interactions between communities, there was also an agreement or cooperation which was often called consensus.

Dahrendorf (1990) also said that society had a dual side, namely having a conflict side and cooperation side, so in the struggle for political power, elites and elite groups would face two situations, namely conflict and consensus. On the one hand, the political elite would face differences, competition, and conflict with other elites, on the other hand, it would also allow for cooperation or consensus among these political elite. There was bargaining between political elites that was mutually beneficial, so that the needs and interests of each political elite were accommodated.

The emergence of conflict according to Dahrendorf's view (1990) stemed from people living together and laying the foundations for forms of social organization, where there were positions of elites who had ruling power in certain contexts and controlled certain positions, and there were other positions. where the residents were subjected to orders. So, in general, there were two basic objectives for every conflict, namely obtaining and maintaining resources.

Each conflict would be fought for various purposes. The objectives of the conflict were as follows: the parties involved in the conflict had the same goal(s), namely both seeked to obtain the resources; on the one hand, wanted to get; while on the other hand, strived to maintain the resources they have (Peters et al., 2005). as shows Table 3.

| Table 3 Indicators of Ralf Dahrendorf's Theory |

|

|---|---|

| Theory | Indicators |

| Conflict Ralf Dahrendorf | Existence of resources |

| Legitimate power | |

| Interests | |

| Changes in Society | |

The Theory of Pruitt and Rubin

Furthermore, Pruitt & Rubin (2004) revealed that conflict was the perception of different interests or a belief that the aspirations (desires, ideals) of the conflicting parties could not be achieved concurrently but what was meant by interest was people’s feelings about what they really wanted. These feelings tended to be central in people's thoughts and actions, formed the core of many of their attitudes, goals, and intentions.

There are several dimensions can be used to explain interests. Some interests were universal, such as the need for security, identity, happiness, clarity about the world, and some physical human values. Some other interests were specific to certain actors, for example, a desire of a nation to be free from a colonialism. Some interests were more important/virtue than others, and the level of virtue was different for each person (Pruitt & Rubin, 2004). as shows in Table 4.

| Table 4 Indicators of Pruitt's and Rubin's Conflict Theory |

|

|---|---|

| Theory | Indicators |

| Conflict (Pruitt dan Rubin) | Differences of interest |

| Aspirations or desires | |

| Differences in perception | |

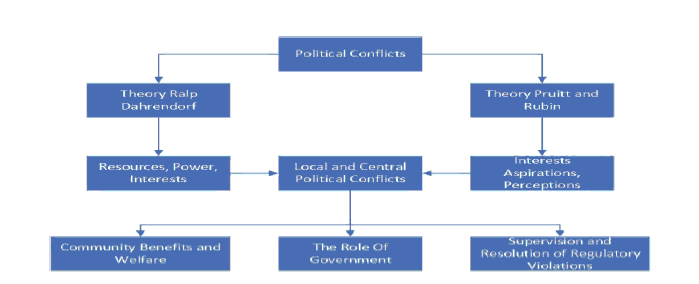

Relationship between Karl Mark's Social Class Theory, Ralph Dahrendrof's Theory, and Pruitt and Rubin's Theory

This study sought to explain the relationship between the conflict theories above with the aspects of benefits and community welfare, the role of the government, monitoring, and settlement of regulatory violations against the implementation of post-mining policies. The social class theory raised by Karl Mark saw conflict arised because of class opposition which was dominated by a very large upper class, where the working class (proletariat) was controlled by the capitalists so that they become isolated. This situation showed that there was a clear division between the parties in power and those in control. Both had different and conflicted interests (Ismail & Mohamad Ramli, 2012).

This study was relevant to Karl Mark's conflict theory, where the emergence of conflict was caused by an unfair distribution of income, if you look at the aspect of this study regarding the causes of political conflict, aspects of benefits and community welfare were the trigger for conflict because the community did not feel there was a fair distribution of income, so that the community did not feel the benefits of mining and the welfare of community life with mining activities. Likewise, this conflict occurred because of class clashes, namely between local communities and companies, because the company as the upper group owned the capital while the local communities were the controlled lower classes, so that class conflict became the trigger for political conflict. Also, there was an awareness from local communities of their position had been explored by the authorities, so that local communities resisted mining activities by rejecting mining policies in their area.

Dahrendorf's conflict theory (1990) also argued that conflict arose to maintain the resources that had been owned so far. Humans wanted to maintain the resources that belong to them, and tried to maintain from other parties who had tried to seize or control these resources. This conflict rised not only because they wanted to defend their dignity, the safety of their life and family, but also to defend the territory or living area, wealth and power possessed so that the conflict became a political resistance for some parties to the party in power.

This study had a close relationship with Dahrendorf's conflict theory (1990), the indicator of resource struggle was the cause of conflict, in this study, the conflict was caused by the resistances from local communities against the implementation of mining policies because they wanted to maintain existing resources; on the indicators of interest, the conflict between local communities and the central emerged because local communities did not feel the benefits and welfare of mining. The local communities wanted a change in the implementation of post-mining policies by paying attention to monitoring and resolution of regulatory violations, but the government's attitude was more in favor of the company. Dahrendorf's conflict theory (1990) was very relevant to this study, local and central political conflicts in the implementation of post-mining policies that occurred in the province of East Kalimantan was due to the existence of different interests between conflicting parties.

Meanwhile, this study also looked at Pruitt and Rubin's conflict theory (2004) that conflict rose because of different positions, either the interests fought for or the aspirations seen by each group. This difference which eventually became the potential conflict. Political conflicts would occur if the aspirations of other parties were not fulfilled. Pruitt and Rubin's conflict theory (2004) was very relevant to this study, that the causes of conflict in different perceptions about interests or a belief in the aspirations of the conflicting parties were not fulfilled.

This theory is quite relevant for studying local and central political conflicts in the implementation of post-mining policies in East Kalimantan province with aspects such as community benefits and welfare, the role of the government, as well as monitoring and regulatory violations. The existence of a perception that mining activities carried out did not offer benefits and welfare for local communities, as well as the role of the government which was considered to be more in favor of the interests of the company, and weak monitoring and resolution of regulatory violations were considered to be in favor of the government's side which aligned with the interests of companies. These differences in interests eventually led to resistance or rejection of mining activities.

Likewise for aspirations that were not in line with the interests of the communities that the existing post-mining policies were not in accordance with the communities’ will. The implementation of post-mining policies was considered not to meet the aspirations of local communities, post-mining policies were considered more in favor of the aspirations of mining companies. So, it led to a rejection of post-mining policies, which resulted in local community resistance to the central government because of policy aspirations that were not in accordance with the interests of the local communities. as shows in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Relationship Between Political Conflict Theory and Political Conflict in Post Mining Policy Implementation

Source: Modified from Dahrendorf (1990); Pruitt & Rubin (2004).

Based on the description above and the suitability of helping this study to answer its objectives, Ralf Dahrendorf's Theory and Pruitt and Rubin's Theory were seen more appropriate by this study, because it was considered more appropriate and suitable in describing the direct relationship between the indicators of the conflict theories and the conflict aspects that wanted to be outlined in this study.

Discussion

Coal mining activities in East Kalimantan Province had negative impacts on the communities living in the coal mining areas due to environmental damages including damages to agricultural areas, damages to public infrastructure, death, air pollution, floods, and the emergence of post-mining political conflicts (Fatah, 2008; Mining Advocacy Network, 2017). The government was required to enforce regulations for coal mining to carry out post-mining responsibilities so they did not neglect regulations (Puluhulawa, 2011). However, in practice, based on the previous data, there were still many mining companies failed to meet their obligations. This issue rose political conflicts between local communities and the central government.

Mining activities in East Kalimantan Province had given various impacts, either positive and or negative (Fünfgeld, 2016). Meanwhile, the negative impacts that occurred before the mining operations started, during mining operations, and post-mining operations, had given a rise to political conflicts (Thaler & Anandi, 2017). This political conflicts occurred due to land ownership, unfair compensation, unfair distribution of resources, environmental degradation, poverty caused by mining, and conflicts over human rights violations (Abuya, 2018). Bartos & Wehr (2002) stated that conflict was a situation where there were conflicts and hostility between actors in achieving a certain goal, namely the common interest. According to him, there were criterias for conflict situations, namely conflict, hostility, and conflict behaviors.

Political conflicts that arose in the form of resistance and opposition to coal mining activities, such as demonstrations from local communities, scholars, associations of farmers and fishermen, environmental groups, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), activists of Wahana Lingkungan Hidup (WalHi), and Mining Advocacy Network (Jatam) which concerned about mining by taking environmental restrictions (Subarudi et al., 2016). This resistance and contradiction arose because they considered coal mining activities to be destructive to the surrounding environment and can destroy the future of the people of East Kalimantan (Jatam, 2017; Siburian, 2016).

In theory, the causes of political conflict can be seen not only as a single factor, but also consisting of several factors, namely structural, interests, values, relationships between humans, and data. The structural problems discussed were the causes of political conflicts related to power, parties in power, public policies either in the form of laws and regulations or other formal policies, and as well as geographical issues and historical factors (Kristiyono, 2008).

Regarding the demand for post-mining policies implementation in East Kalimantan Province for its implementation to be carried out correctly and in accordance with the objectives that had been formulated so it would not damage the surrounding environment and to repair the damages in the aspects of environmental, social, the economy of the communities affected by coal mining sued the Provincial Government and the Central Government. It can be analysed that the factors that caused political conflict were due to structural issues, namely regulatory policies, in this case, the Government Regulation No. 78/2010 concerning reclamation and post-mining.

The following were some studies of political conflicts that arose due to mining implementation like Davidman (2017), post-mining activities that were not in accordance with the documents of post-mining implementation had resulted in political conflicts in the communities. A study conducted by Irwandi & Chotim (2017) stated that the causes of political conflicts were the absence of a socialisation process, the local/rural government was less transparant and open to the communities, and differences in interests.

Further, according to Mahrudin (2010), what contributed to political conflicts was the lack of communication between the company and the communities, there were intransparency of compensation for land and plants for local communities and in workers hiring/recruitment procedure. In the study conducted by Subarudi, et al., (2016) the causes of political conflict were the weak law enforcement in the mining sector which did not align with government policies, overlapped permits, lacked of communication, and did not carry out the reclamation of mined lands.

In line with the study conducted by Bradshaw (2009), the cause of political conflict was that local people experienced little benefit from mining revenues, the government shown no effort and political will to control mining and manage local conflicts, the mining companies had created serious problems in relations with local communities. A study conducted by Hilson (2002), the causes of political conflict to arise were due to irreversible environmental damages and poor corporates/commpanies communications. Therefore, it was the nature of mining operations that had led to the phenomenon of this inevitable emergence of political conflicts with local communities. Abuya (2018), the causes of the emergence of political conflicts were due to unilateral confiscation of community land by the state, environmental degradation due to failed reclamation, unfair benefits enjoyed by the communities. Mensah & Okyere (2014), the causes of political conflict, namely the problem of compensation, resettlement, and the impact of public health.

In this study, the reasons for the emergence of political conflict were due to several things, namely the benefits and welfare of the community; less perceived benefits and welfare for local communities which lived around the mining area, the role of the government; to the existence of resolution for mining problems was too slow and appeared to have no capacity and political will to regulate the mining industry and manage conflicts, supervise and resolve regulatory violations; which provided no certainty to the communities.

Therefore, post-mining policies were needed to implement post-mining policies to be more effective with the objectives of reducing environmental damages and resolving the social, economic, and cultural impacts of communities living in mining areas to prevent the emergence of post-mining political conflicts. The implementation of post-mining policies in East Kalimantan Province had not been running effectively (Alting, 2013; Jatam, 2017; Muhdar et al., 2015).

This study attempted to explore local and central political conflicts resulting from the impact of implementing post-mining policies that were not in accordance with the existing regulations. This study sought to describe the political conflicts that occurred in East Kalimantan Province due to mining by looking at the aspects of the benefits and welfare of the communities, the role of the government, monitoring and resolving of regulatory violations.

Based on the problems with post-mining policies as discussed above, it was necessary to resolve local and central political conflicts in the implementation of post-mining policies. This conflict resolution was an effort to reformulate a resolution of conflicts that occurred to reach a new agreement that would be more acceptable to the conflicting parties. Conflict resolution had the objectives of knowing the existence of conflicts and it was directed at the involvement of various parties in fundamental issues so that they could be resolved effectively (Bercovitch, 2019).

Dahrendorf (1990) stated that there are three approaches of conflict management can be used as conflict resolution, namely conciliation; where all parties discuss and debate openly to reach an agreement without any party imposing their will, mediation; when both parties agree to seek advice from a third party, arbitration; both parties agree to get a final legal decision from the arbitrator as a way out to resolve the conflict (Keethaponcalan, 2017; Zafirah et al., 2017).

According to Dahrendorf (1990), negotiation was the first step taken when the desire to make peace appeared on the conflicting parties. Therefore, negotiation was the safest step at the beginning of the negotiation period. If the negotiations had not found a solution, then mediation would be used. Mediation was a process in which the conflicting parties with the help of an intermediary identified the issues that were being disputed to find a solution and an alternative based on mutual agreement as a conflict resolution.

Resolution of conflicts that had occurred in coal mining in East Kalimantan, several ways could be done in resolving this ongoing conflict, although the effects of this conflict resolution could not be guaranteed for its success in resolving post-coal mining political conflicts that had been planted by the people of East Kalimantan. Due to the existence of many actors taken role in the exploitation of coal mining companies. As for how to resolve post-coal mining political conflicts in East Kalimantan, namely first; through negotiation counselling with the local government, local people who felt that there was a discrimination or post-coal mining activities that provided no benefits and welfare could have done an approach by conveying their aspirations or opinions through a forum provided by the local government.

Second, people who felt that post-coal mining activities were considered detrimental to them and were affected by mining could have taken an approach by doing negotiations with the East Kalimantan Regional House of Representatives (DPRD) and with the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM).

Factors Causing the Emergence of Political Conflict

Community Benefits and Welfare

According to Law Number 4 of 2009, mining activities can increase local, regional, and state income and create maximum employment opportunities for the welfare of the people. This was so that mining could provide benefits and prosperity to local communities, especially those who lived around mining sites. However, local people did not feel the benefits and welfare of mining activities (Wibowo & Ardian, 2014). The negative impacts of mining felt by the communities were exceptionally large (Manik, 2013). Generally, the mining industry produced a large amount of waste, one of which was in the form of tailings and several mines produced toxic heavy metals. The tailings from mining contained several types of heavy metals, such as arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead at high levels. Further, if the ex-mining land was not restored, it would become a giant puddle or the form an arid land (Bell & Donnelly, 2006).

The result of this mining impact had generated community resistance, both against mining companies and the government. Local communities rejected the existence of mining policies that were considered to have destroyed the environment and have not provided benefits and welfare to them (Bell & Donnelly, 2006). The impact of mining extracts had resulted in social conflicts which in return became political conflicts, such as a study conducted by Coser (1957) on the occurrence of political conflicts between the state and citizens in mining activities, especially after mining/post-mining.

Role of Government

The role of the government is to overcome problems that arose as a result of the existing mining activities and to protect the community from the dangers of pollution and other hazards such as land sliding, flooding, and death due to mining pits that were left open after mining. However, in its implementation, the role of the government was not as expected to be by the communities, the government's attitude was more in favor of mining companies, this was because the government seemed to have no desire to create regulations regarding mining that were in favor of the communities’ interests and also no desire to resolve conflicts that occurred between communities and mining companies (Sondakh, 2017).

As a result, tensions arose between the communities and the government, local people rejected mining policies, local people felt that the existing post-mining policies only sided with the interests of the authorities and detrimented to them (Subarudi et al., 2016). The government's attitude that was felt to be slow in responding to existing mining problems eventually had resulted in the political conflict between local communities and the government. Started from the social conflicts that had arisen to resistance to the government by rejecting the post-mining policies made by the government (Asnidar, 2017).

Monitoring and Resolution of Regulatory Violations

Monitoring was needed to determine, assess and implement corrective actions, if necessary, to comply with the plan. Monitoring was needed in a series of coal mining activities so as not to deviate from the stated objectives and to ensure that mining activities did not breach the established regulations (Butar, 2010). However, in its implementation, the monitoring of mining activities carried out by the government had not been maximised, this was because it had not been coordinated in an integrated manner between sectoral institutions, so that monitoring was more cross-sectoral so it became ineffective (Puluhulawa, 2011).

The lack of monitoring carried out by the government on mining activities had resulted in violations of regulations committed by mining companies. One of them was the company's obligation to carry out reclamation and post-mining activities that were not carried out. So this raised community resistance and led to political conflict (Azis, 2017; Ishak et al., 2017).

Conclusion

Local and central political conflicts in East Kalimantan Province occurred due to community resistances by groups of farmers, scholars, NGOs (JATAM and WALHI) against the implementation of post-coal mining policies issued by the government which was considered to have negative impacts on the environment, social, and people’s economy. Coal mining activities in East Kalimantan Province were considered to be destroyers and killers of the communities because of violations of regulations and human rights (HAM). The implementation of post-mining policies provided no benefits and welfare for local communities, the role of the government was very slow in resolving conflicts caused by post-coal mining activities, weak government oversight on post-mining activities, and weak resolution in resolving regulatory violations in post-mining activities that were not in accordance with the existing regulations.

References

- Abood, S.A., Lee, J.S.H., Burivalova, Z., Garcia?Ulloa, J., & Koh, L.P. (2015). Relative contributions of the logging, fiber, oil palm, and mining industries to forest loss in Indonesia. Conservation Letters, 8(1), 58-67.

- Abuya, W.O. (2016). Mining conflicts and corporate social responsibility: Titanium mining in Kwale, Kenya. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3(2), 485-493.

- Abuya, W.O. (2018). Mining conflicts and corporate social responsibility in kenya’s nascent mining industry: A call for legislation. In Social Responsibility. United Kingdom: Intech Open.

- Akabzaa, T., & Darimani, A. (2001). Impact of mining sector investment in Ghana: A study of the Tarkwa mining region. Third World Network, 12, 47-61.

- Al-fatah, A.F. (2014). Analysis of growth and inequality of economic development between regions in South Sumatra Province in 2006-2011. University of Muhammadiyah Malang, Malang.

- Alting, H. (2013). Land tenure conflicts in North Maluku: people versus rulers and entrepreneurs. Journal of Legal Dynamics, 13(2), 266-282.

- Avruch, K., & Mitchell, C. (2013). Conflict resolution and human needs: Linking theory and practice: Routledge.

- Baillien, E., & De Witte, H. (2009). The relationship between the occurrence of conflicts in the work unit, the conflict management styles in the work unit and workplace bullying. Psychologica Belgica, 49(4), 207.

- Barron, P., Diprose, R., & Woolcock, M. (2007). Local conflict and development projects in Indonesia: part of the problem or part of a solution? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper(4212).

- Bartos, O.J., & Wehr, P. (2002). Using conflict theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Baruya, P. (2009). Prospects for coal and clean coal technologies in Indonesia. London: IEA Clean Coal Centre.

- Bebbington, A., Hinojosa, L., Bebbington, D.H., Burneo, M.L., & Warnaars, X. (2008). Contention and ambiguity: Mining and the possibilities of development. Development and change, 39(6), 887-914.

- Belkin, H.E., Tewalt, S.J., Hower, J.C., Stucker, J., & O'Keefe, J. (2009). Geochemistry and petrology of selected coal samples from Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua, Indonesia. International Journal of Coal Geology, 77(3-4), 260-268.

- Bell, F.G., & Donnelly, L.J. (2006). Mining and its impact on the environment. CRC Press.

- Benedict, R., & Mead, M. (2019). Race: Science and politics. University of Georgia Press.

- Bercovitch, J. (2019). Social conflicts and third parties: Strategies of conflict resolution. Routledge.

- Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2010). State capacity, conflict, and development. Econometrica, 78(1), 1-34.

- Bian, Z., Dong, J., Lei, S., Leng, H., Mu, S., & Wang, H. (2009). The impact of disposal and treatment of coal mining wastes on environment and farmland. Environmental Geology, 58(3), 625-634.

- Borkan, J.M. (2004). Mixed methods studies: A foundation for primary care research. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2(1), 4-6.

- Bradshaw, S. (2009). Mining conflicts in Peru: Condition critical. Retrieved from United States.

- CNN Indonesia. (2019). Coal giant company in East Kalimantan, the new capital city. CNN Indonesia.

- Coser, L.A. (1957). Social conflict and the theory of social change. The British Journal of Sociology, 8(3), 197-207.

- Creswell, J.W., Hanson, W.E., Clark Plano, V.L., & Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The counseling psychologist, 35(2), 236-264.

- Cunneen, C. (2001). Conflict, politics and crime: Aboriginal communities and the police. Conflict, Politics and Crime: Aboriginal Communities and the Police.

- Dahrendorf, R. (1990). The modern social conflict: An essay on the politics of liberty. Univ of California Press.

- Davidman, S.D. (2017). Study of the use of ex-mining holes (voids) as a form of conflict resolution in the final stage of the mine (Study on Void Ex Pit 7 PT. Sarolangun Prima Coal). Andalas University, Padang.

- Davis, P.S., & Harveston, P.D. (2001). The phenomenon of substantive conflict in the family firm: A cross?generational study. Journal of small business management, 39(1), 14-30.

- Eagles, M. (2005). Politics is local: National politics at the grassroots: Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press.

- Earl, J. (2011). Political repression: Iron fists, velvet gloves, and diffuse control. Annual review of sociology, 37, 261-284.

- Fatah, L. (2008). The impacts of coal mining on the economy and environment of South Kalimantan Province, Indonesia. ASEAN economic bulletin, 85-98.

- Francis, D. (2011). New thoughts on power: Closing the gaps between theory and action.

- Fünfgeld, A. (2016). The state of coal mining in East Kalimantan: Towards a political ecology of local stateness. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 9(1), 147-162.

- Ghose, M.K., & Majee, S. (2000). Sources of air pollution due to coal mining and their impacts in Jharia coalfield. Environment International, 26(1-2), 81-85.

- Ginting, D. (2010). Coal management policy and prospects in Indonesia. Geological Resources Bulletin, 5(1), 43-49.

- Henry, G.T., & Mark, M.M. (2003). Beyond use: Understanding evaluation’s influence on attitudes and actions. American Journal of Evaluation, 24(3), 293-314.

- Heywood, A. (2015). Political theory: An introduction. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Hilson, G. (2002). An overview of land use conflicts in mining communities. Land use policy, 19(1), 65-73.

- Irwandi, I., & Chotim, E.R. (2017). Conflict analysis between society, government and private. JISPO: Journal of Social and Political Sciences, 7(2), 24-42.

- Ishak, M.I.S., Ishak, N.F.A., Hassan, M.S., Amran, A.Z.L.A.N., Jaafar, M.H., & Samsurijan, M.S. (2017). The role of multinational companies for world sustainable development agenda. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag, 12, 228-252.

- Ismail, I., & Mohamad, R.Y. (2012). Karl marx and the concept of social class struggle. International Journal of Islamic Thought, 1, 27-33.

- Jacobson, G.C., & Carson, J.L. (2019). The politics of congressional elections: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Jaringan, A.T. (2017). Indonesia national human right commisions report of human right abuses on abandon coal pit mining case in east Kalimantan. Retrieved from Kalimantan Timur:

- Jatam, K. (2017). Victims continue to fall in the mine pits, where the state. in.

- Jati, W.R. (2013). Local wisdom as a religious conflict resolution. Walisongo: Journal of Religious Social Research, 21(2), 393-416.

- Jeong, H.W. (2008). Understanding conflict and conflict analysis: Sage.

- Konting, M.M. (1990). Methods of educational research. Kuala Lumpur: Language and Library Council.

- Kristiyono, N. (2008). Conflict in the Affirmation of Regional Boundaries between Magelang City and Magelang Regency (Analysis of the Causes and Impact Factors). Diponegoro University, Semarang.

- Kuo, C.S. (2012). The mineral industry of Indonesia. In Mineral years book. Washington DC: U.S. Government printing office.

- Kuter, N. (2013). Reclamation of degraded landscapes due to opencast mining. In Advances in landscape architecture. London: IntechOpen.

- Lingard, H., & Francis, V. (2006). Does a supportive work environment moderate the relationship between work?family conflict and burnout among construction professionals? Construction Management and Economics, 24(2), 185-196.

- Listiyani, N. (2017). The impact of mining on the environment in south kalimantan and its implications for citizens' rights. Al Adl: Journal of Law, 9(1),67-86.

- Mac Ginty, R., & Williams, A. (2016). Conflict and development. Routledge.

- MacKinnon, K., Hatta, G., Halim, H., & Mangalik, A. (1996). The ecology of Kalimantan, the ecology of Indonesia series III. Singapore: Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

- Mahrudin, M. (2010). Mining policy conflict between government and community in buton regency. Journal of Government Studies,1(1), 203-222.

- Malone, M.P. (2012). The battle for butte: Mining and politics on the northern frontier, 1864–1906: University of Washington Press.

- Manik, J.D.N. (2013). Environmental impact mining management in Indonesia. PROMINE, 1(1).

- Mehta, L. (2013). The limits to scarcity: Contesting the politics of allocation. Routledge.

- Mensah, S.O., & Okyere, S.A. (2014). Mining, environment and community conflicts: A study of company-community conflicts over gold mining in the Obuasi Municipality of Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Development Studies, 5(1), 1-9.

- Mink, G. (2019). Old labor and new immigrants in American political development: Union, party, and state, 1875-1920. Cornell University Press.

- Mitchell, J.M., & Mitchell, W.C. (1969). Political analysis & public policy: An introduction to political science. Chicago: Rand McNally.

- Muhdar, M., Nasir, M., & Rosdiana, R. (2015). Legal implications for the practice of borrowing and using forest areas for coal mining activities. Hasanuddin Law Review, 1(3), 430-451.

- Nel, E.L., Hill, T.R., Aitchison, K.C., & Buthelezi, S. (2003). The closure of coal mines and local development responses in Coal-Rim Cluster, northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 20(3), 369-385.

- Nix, C.L., & Hale, C. (2007). Conflict within the structure of peer mediation: An examination of controlled confrontations in an at?risk school. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 24(3), 327-348.

- Northcott, M.S. (2013). A political theology of climate change. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

- Peters, B.G., Pierre, J., & King, D.S. (2005). The politics of path dependency: Political conflict in historical institutionalism. The journal of politics, 67(4), 1275-1300.

- Pruitt, D.G., & Rubin, J.Z. (2004). Social conflict theory, trans. Helly P. Soetjipto and Sri Mulyantini, Yogyakarta: Student Library.

- Puluhulawa, F.U. (2011). Supervision as an instrument for law enforcement in the management of mineral and coal mining businesses. Journal of Legal Dynamics, 11(2), 306-315.

- Rauf, M. (2001a). Political consensus and conflict. Jakarta: Director General of Higher Education.

- Rauf, M. (2001b). Political consensus and conflict. Jakarta: Directorate General of Higher Education Ministry of National Education.

- Resosudarmo, B.P., Alisjahbana, A., & Nurdianto, D.A. (2012). Energy security in Indonesia. In Energy Security in the Era of Climate Change (pp. 161-179). United Kingdom: Springer.

- Ripley, E.A., & Redmann, R.E. (1995). Environmental effects of mining. United Kingdom: CRC Press.

- Sassoon, A.S. (2019). Gramsci's politics: Routledge.

- Samsurijan, M.S., Abd Rahman, N.N., Ishak, M.I.S., Masron, T.A., & Kadir, O. (2018). Land use change in Kelantan: Review of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports. Geografia-Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 14(4).

- Schillewaert, N., Langerak, F., & Duharnel, T. (1998). Non-probability sampling for WWW surveys: A comparison of methods. Market Research Society. Journal., 40(4), 1-13.

- Seliger, M. (2019). Ideology and politics. Routledge.

- Serneels, P., & Verpoorten, M. (2015). The impact of armed conflict on economic performance: Evidence from Rwanda. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 59(4), 555-592.

- Sheoran, V., Sheoran, A., & Poonia, P. (2010). Soil reclamation of abandoned mine land by revegetation: A review. International Journal of Soil, Sediment and Water, 3(2), 13.

- Si, H., Bi, H., Li, X., & Yang, C. (2010). Environmental evaluation for sustainable development of coal mining in Qijiang, Western China. International Journal of Coal Geology, 81(3), 163-168.

- Siburian, R. (2016). Coal mining: Between gaining rupiah and spreading the potential for conflict. Indonesian Society, 38(1), 69-92.

- Soekanto, S. (2006). Introduction to legal research. Publisher University of Indonesia (UI-Press).

- Spradley, J.P., Elizabeth, M.Z., & Amirudin. (1997). Metode etnografi. Tiara Wacana Yogya.

- Subarudi, R., Kartodihardjo, H., Soedomo, S., & Sapardi, H. (2016). Coal mining business policy in forest areas: A case study of east kalimantan. Journal of Forestry Policy Analysis, 13(1), 53-71.

- Suhardjana, J. (2009). Manage environmental conflicts in order to realize sustainable regional development. Bumi Lestari Journal of Environment, 9(2), 300-305.

- Sunderlin, W.D. (1999). The effects of economic crisis and political change on Indonesia's forest sector, 1997-99. New Jersey: Citeseer.

- Surbakti, R. (1992). Understanding political science. Jakarta: Grasindo.

- Taulman, J.F., & Robbins, L.W. (2014). Range expansion and distributional limits of the nine?banded armadillo in the United States: An update of Taulman & Robbins (1996). Journal of Biogeography, 41(8), 1626-1630.

- Thaler, G.M., & Anandi, C.A.M. (2017). Shifting cultivation, contentious land change and forest governance: The politics of swidden in East Kalimantan. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(5), 1066-1087.

- Thielemann, T., Schmidt, S., & Gerling, J.P. (2007). Lignite and hard coal: Energy suppliers for world needs until the year 2100—An outlook. International Journal of Coal Geology, 72(1), 1-14.

- Wehr, P. (2019). Conflict regulation: Routledge.

- Wibowo, A.P., & Ardian, A. (2014). Analysis of the socio-economic benefits of the limestone mining business of PT. XYZ in West Bandung Regency, West Java Province. Journal of Mining Engineering Study Program, Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB).

- Wolff, J.L., Starfield, B., & Anderson, G. (2002). Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Archives of internal medicine, 162(20), 2269-2276.

- Wolman, H., & Page, E. (2002). Policy transfer among local governments: An information–theory approach. Governance, 15(4), 577-501.

- Work, C. (2019). Climate change and conflict: Global insecurity and the road less traveled. Geoforum, 102, 222-225.

- Zafirah, N., Nurin, N.A., Samsurijan, M.S., Zuknik, M.H., Rafatullah, M., & Syakir, M.I. (2017). Sustainable ecosystem services framework for tropical catchment management: A review. Sustainability, 9(4), 546.

- Zhengfu, B., Inyang, H.I., Daniels, J.L., Frank, O., & Struthers, S. (2010). Environmental issues from coal mining and their solutions. Mining Science and Technology (China), 20(2), 215-223.