Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Masstige Value of Smartphone Brands: Impact on Egoistic Value Orientation of Indian Consumers

Ruchi Gupta, Shaheed Bhagat Singh College, University of Delhi

Kiran S Nair, Abu Dhabi School of Management

Keywords:

Masstige Marketing, Masstige Mean Index, Egoistic Value Orientation

Abstract

The study examines two smartphone brands (Apple and Samsung) in order to determine their masstige value in the Indian market. Our research also looks into consumer's egoistic value orientation in relation to purchase of masstige brands. The masstige value of Apple's iPhone and Samsung's Smartphone was determined using Masstige Mean Score Scale (MMSS) developed by Paul (2015). Structural equation modelling was used to investigate the impact of brand masstige value on consumer egoistic value orientation. According to our MMI analysis, as far as generating mass prestige value in the Indian market is concerned, the Apple i-Phone (American brand) outperformed the Samsung Smartphone (Korean brand). Furthermore, our data show that the Apple iPhone has a positive and significant impact on people's egoistic value orientation. In the case of the Samsung smartphone, however, masstige marketing methods were found to be ineffective in changing buyers' egoistic value orientation. This indicates that although the purchase of an Apple iPhone shall meet a consumer's ego needs (as a significant and positive egoistic value orientation is developed), the same cannot be stated for Samsung Smartphone purchasers. The possible reasons for the same are discussed.

Introduction

“The term ‘masstige’ stands for mass prestige” (Paul, 2018). The term refers to increased brand perception and brand equity. In layman's words, the term has been described as "prestige for the masses," a mix of mass and prestige (Paul, 2015). Since marketing theory lacked a grasp of how and why only a few firms are able to establish brand equity in international markets, especially in the era of globalisation, the concept of masstige strategy and theory was introduced (Paul, 2018).

Mass prestige brands are positioned between luxury and mid-priced brands when we consider price and status (Truong et al., 2009). As a result, “masstige marketing may be defined as a phenomenon in which ordinary products with somewhat high prices” are pushed to the widest possible audience by building mass prestige rather than lowering prices or offering discounts (Paul, 2018). By combining prestige with realistic price premiums, brand positioning strategies have been found to be effective in attracting middle-class buyers. Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Starbucks, Apple and other high-end brands are examples of masstige brands. Strategies for luxury brands, which sustain status and substantial price premiums to maintain brand exclusivity and distinctiveness, differ significantly from these tactics. As a result, the things are available on the market but are just out of reach for the average shopper (Paul, 2018).

There is a rising recognition that one of a company's most valuable intangible assets is its brand (Keller & Lehmann, 2006). Masstige marketing is that part of a company’s strategy that aims to obtain market share and manage brands in the age of globalisation.

According to Silverstein & Friske (2003), the scope of research in the area of masstige marketing in emerging countries is significantly broader since there are more things that are generally regarded as "expensive" yet affordable to "middle class" and "upper low-income" clients. Among the products on the list are automobiles, jewellery, laptops, smartphones, cosmetics, fragrances, and televisions. Researchers might conduct studies to evaluate the masstige values of prestige brands from these different industries using data from emerging economies (Paul, 2018).

This prompted us to undertake this study to understand the mass prestige value of smartphone brands in a developing country, India. Additionally, the concept of 'masstige' is very new in marketing theory, and it is still an under-researched topic. There are few explanations for why customers’ attitudes toward multinational brands differ (Steenkamp & de Jong, 2010; Riefler, 2012). Furthermore, only a few empirical studies have looked into the consumer behaviour in relation to the influence of masstige marketing strategies (Truong et al., 2009). We also discovered that there are few insights into the relationship between a brand's masstige value and a consumer's motivation to satisfy his or her ego needs when purchasing this "near luxury" product. Our paper aims to propose the novel notion of a consumer's egoistic value orientation in order to better understand consumer behaviour while purchasing masstige brands.

We provide a number of contributions to the scant masstige marketing literature. First, we build on previous masstige marketing research by assessing the masstige value of two top-of-mind smartphone brands in a developing country. Second, we investigate the relationship between a brand's mass prestige value and customer's egoistic value orientation when purchasing a smartphone brand.

To fill in the gaps in the literature, we have expanded previous research with the following specific objectives of the study:

1. Using the Masstige Mean Index (MMI), calculate and compare the perceived mass prestige of two smartphone brands in India.

2. Investigate the relationship between a brand's masstige value and a customer's egoistic value orientation when purchasing a smartphone brand.

The following is the order in which this article is presented. The literature review and research hypotheses are presented in the next section. Section 3 discusses the research methodology. The data analysis and results are covered in section 4. Section 5 further discusses the findings. Section 6 examines the limitations of the study as well as future research directions, while Section 7 provides concluding remarks.

Literature Review

Masstige Marketing

In a Harvard Business Review article about middle-class consumer behaviour in the United States, Silverstein & Fiske (2003) invented the word "masstige." The pricing range for masstige items, which are similar to luxury goods, is between midrange and super-premium. Silverstein & Fiske (2003) in the HBR article stated that the number of middle-class consumers is expanding and many consumers are demanding better levels of product quality. Furthermore, luxury goods are no longer just for the wealthy, but are becoming more accessible to the general public.

Many businesses are abandoning traditional techniques of acquiring customers in favour of experimenting with and figuring out innovative ways to tap into the market's potential. Brand positioning techniques have been shown to attract middle-class customers by combining prestige with affordable price premiums.

Thus, masstige marketing is characterised as a phenomena where normal products with somewhat high prices are promoted to attract the broadest possible audience by establishing mass prestige rather than cutting prices or offering discounts (Paul, 2018). The term "masstige strategy" refers to a brand positioning plan that aims to increase the brand's mass prestige value.

Mass Prestige and Branding

Masstige marketing refers to the marketing strategy of penetrating the market for brands that are considered prestigious but at the same time within the reach of middle-class customers too. Because industry practitioners frequently utilise brand positioning tactics to enhance market share and profitability of premium brands, the issue of masstige marketing is highly significant. In the long term, prestige marketing aids in the attempts to build a high degree of mass prestige for the brand. The masstige strategy approach may be used to a wide range of prestige brands, including high-end apparel, automobiles, smartphones, laptops, desktop computers, and five-star hotels (Paul, 2015).

Kapferer (2012) demonstrated how luxury companies might enter large global markets, particularly growing Asian markets, without sacrificing their exclusivity. Many people must be aware of the brand, its products, and its pricing, even if only a few can afford them (Kapferer, 2012).

Furthermore, the masstige marketing approach also entails downward brand extension strategy to be adopted by the prestige brand (Paul, 2018). As said earlier, unlike luxury goods, mass prestige brands are offered at a lower price point, giving buyers a sense of exclusivity (Silverstein & Fiske, 2003). However, how thin can you go on pricing? This is an intriguing subject that, if not managed properly, might have an impact on the brand's masstige value.

In this study, we assess the masstige mean index (MMI) value of two smartphone brands in the Indian market: Apple (American) and Samsung (Korean). Prior research in the field of masstige marketing and brand equity has discovered that country of origin may have a major influence on brand equity while also contributing to the prestige of a brand (Roth, Diamantopoulos & Montesinos, 2008; Mohd-Yasin et al., 2007; Steenkamp, Batra & Alden, 2003; Kumar & Paul, 2018). Thus, the following is the hypotheses in our study.

H1: Certain brands within the same sector have a larger masstige value, resulting in improved brand equity and popularity in foreign markets.

Egoistic Value Orientation

Truong, et al., (2009) created a brand positioning model based on masstige marketing principles. Consumers can acquire prestige brands at an affordable price thanks to masstige marketing. When customers purchase these status symbols, they feel a sense of achievement. (Truong et al., 2009). As a result, we might conclude that purchasing high-end brands satisfies people's ego requirements. These are similar to the values of self-improvement (Schwart, 1992, Stern, 2000). People with an egoistic value orientation are more likely to weigh the costs and rewards of a behaviour for themselves (De Groot, 2008).

Thus, we believe that a masstige brand can have a significant and positive impact on customers' egoistic value orientation. This will be fascinating to research because it may have an impact on future purchasing intentions for luxury products. As a result, we posited the following hypothesis in our research.

H2: A brand’s masstige value has a positive and significant impact on the egoistic value orientation of the consumer while considering purchase of the brand For the two brands considered for the study, we thus lay down that

H2a: Apple i-Phone’s masstige value has a positive and significant impact on the egoistic value orientation of the consumer while considering purchase of the brand

H2b: Samsung Smartphone’s masstige value has a positive and significant impact on the egoistic value orientation of the consumer while considering purchase of the brand

Research Methodology

Sample Size, Sampling Design, and Measurement Instrument

In two investigations – Study 1 (Apple) and Study 2 (Samsung), a questionnaire was utilised to collect primary data from respondents in India who were emailed a Google form to acquire replies regarding two brands of smartphones – Apple i-phone and Samsung smartphone. The questionnaire was sent to over 700 people (including students, professionals, homemakers, businessmen, and others) through email and WhatsApp, and replies were received from 105 people for Study 1 and 121 people for Study 2. Thus, the study employed non-probability sampling method.

The demographics of the respondents were covered in the first section of the questionnaire. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the respondents. As can be observed, the majority of the people in our survey belonged to India's middle class. The second section included questions concerning the items that made up the study's constructs: Brand Knowledge and Prestige, Brand’s Perceived Quality, Excitement for and Status of the brand and Egoistic Value Orientation of the consumer for the said brand.

| Table 1 Demographic Profile of the Respondents |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | Category | Study 1 – Apple i-Phone | Study 2- Samsung Smartphone | ||

| Number of respondents | Percent | Number of respondents | Percent | ||

| Gender | Male | 49 | 46.67 | 73 | 60.33 |

| Female | 56 | 53.33 | 48 | 39.67 | |

| Age (years) | 18-35 | 29 | 27.62 | 35 | 28.93 |

| 36-50 | 53 | 50.48 | 58 | 47.93 | |

| Above 50 | 23 | 21.90 | 28 | 23.14 | |

| Education | Undergraduates | 09 | 8.57 | 18 | 14.88 |

| Graduates | 38 | 36.19 | 45 | 37.19 | |

| Postgraduates | 47 | 44.76 | 37 | 30.58 | |

| Doctorates | 11 | 10.48 | 21 | 17.35 | |

| Monthly Family Income | Under Rs. 50,000 | Nil | 0.00 | Nil | 0.00 |

| Rs.50,000-Rs.1,00,000 | 16 | 15.24 | 14 | 11.57 | |

| Rs.1,00,000-Rs.2,00,000 | 56 | 53.33 | 68 | 56.20 | |

| Rs.2,00,000-Rs 5,00,000 | 21 | 20 | 28 | 23.14 | |

| Above Rs 5,00,000 | 12 | 11.43 | 11 | 9.09 | |

| TOTAL | 105 | 121 | |||

The first three constructs of the study were used to calculate the Mass Mean Index Value (MMIV) of the two brands -Apple and Samsung in the smartphone product category. The Masstige Mean Score Scale (MMSS) and Masstige Mean Index (MMI) created by Paul (2015) have been used in this study to measure the mass prestige worth of smartphone brands in the Indian market. Under these criteria, a total of ten items (see Table 2) were listed as questions. These questions were answered on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7, with 1 being "Strongly Disagree" and 7 being "Strongly Agree."

The fourth construct, the consumer's egoistic value orientation toward the brand, was also calculated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7, with 1 being "Strongly Disagree" and 7 being "Strongly Agree." The following are the items of these structures (adapted from De Groot & Steg, 2008 and Han & Lee, 2016).

EVO1: I would like to own this brand of phone as a point of differentiation from other people

EVO2: This phone will give me dominance over others in the society

EVO3: It would be nice to be seen with this phone during my day-to-day activities

Research Techniques Used for the Study

The Kaiser Meyer Olkin was used to evaluate sampling adequacy (KMO). The construct validity of the constructs was verified using EFA in this study. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to evaluate the model's validity (convergent and discriminant), and reliability. Using structural equation modelling, the influence of brand masstige value on customer egoistic value orientation was studied.

Analysis and Results

Calculation of Masstige Mean Index Value

Paul (2015) extended the masstige theory by proposing and validating Masstige Mean Score Scale (MMSS). The Masstige Mean Index (MMI) of a brand is calculated using this scale which consists of 10 questions (see Table 2), with scores ranging from 10 to 70 (ten 7-point Likert Questions means that the minimum mean value can be 10 and maximum mean value can be 70).

This scale may be used to determine the masstige value of prestige brands in a geographical area defined in terms of a country or a region or a state. The score calculated with the help of this instrument reflects the masstige value of the brand. A higher score means a higher masstige value of the brand and a lower score means a lower masstige value of the brand. To get MMIs, data must be collected from a set of respondents consisting of potential or present customers. After this, mean scores must be computed from responses to each question, and then, mean scores of all the items in the scale must be added. Thus, the Masstige Mass Index Value(MMIV) is defined by the sample mean. As Paul (2015) lays down, the primary idea is that the greater the mass mean index value, the larger the equity enjoyed by the brand.

In the Indian market, the MMIV of an Apple iPhone was calculated to be 58.53, while the same for a Samsung smartphone was calculated to be 48.08 (Table 2). This suggests that Apple's iPhone (an American brand) has more brand equity and prestige in India than Samsung's smartphone (Korean brand). As a result, we accept H1, which argues that certain brands within the same sector have a higher masstige value, resulting in increased brand equity and appeal in international markets.

| Table 2 Mass Mean Index for Apple I-Phone and Samsung Smartphone |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Factor Items | Apple | Samsung |

| Brand Knowledge and Prestige (Paul, 2015) | BKP1:I like this brand because of brand knowledge | 6.18 | 5.25 |

| BKP2: I would buy this brand because of its mass prestige | 5.78 | 4.98 | |

| BKP3: I would pay a higher price for this brand for status quo | 5.95 | 4.99 | |

| BKP4: I consider this brand a top of mind in my country | 5.70 | 4.89 | |

| BKP5: I would recommend this brand to friends and relatives | 5.37 | 4.45 | |

| Perceived Quality (Paul, 2015) | PQ1: I believe this brand is known for its quality | 5.63 | 6.04 |

| PQ2: I believe this brand meets international standards | 5.86 | 6.04 | |

| Excitement and Status (Paul, 2015) | ES1: I love to buy this brand regardless of price | 6.09 | 3.77 |

| ES2: Nothing is more exciting than this brand | 5.80 | 3.67 | |

| ES3: I believe that individuals in this country perceive this brand as prestigious | 6.17 | 4.00 | |

| Total Mass Mean Index Value | 58.53 | 48.08 | |

Study 1: Impact of Apple i-Phone’s Masstige Value on the Egoistic Value Orientation of the Consumer while Considering Purchase of the Brand

Results of Exploratory Factor Analysis

Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) test value was 0.829, which is regarded exceptional (Kaiser, 1974). The construct validity of the constructs was confirmed by the results of the principal component rotated matrix. Table 3 displays the factor loadings. The total variance explained was 78.05 percent, which is higher than the needed threshold value of 50 percent.

Validity and Reliability Analysis

Cronbach alpha was used to determine the constructs’ reliability (Nunnally, 1978). To determine the convergent and discriminant validity of our constructs, we used Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA).

From Table 3 it can be seen that α >0.7, AVE>0.5, and α >AVE. Thus, convergent validity is established for the constructs (Hair et al., 2010). Also, as AVE>MSV and AVE>ASV (Table 4), discriminant validity of the constructs is also established (Hair et al., 2010).

| Table 3 Reliability and Convergent Validity – Apple I-Phone |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loadings |

Cronbach Alpha (α) | AVE | Composite Reliability (CR) |

| Brand Knowledge and Prestige (BKP) | BKP1 BKP2 BKP3 BKP4 BKP5 |

0.782 0.883 0.826 0.835 0.704 |

0.902 | 0.662 | 0.909 |

| Perceived Quality (PQ) | PQ1 PQ2 |

0.651 0.588 |

0.739 | 0.592 | 0.740 |

| Excitement and Status (ES) | ES1 ES2 ES3 |

0.846 0.819 0.889 |

0.858 | 0.682 | 0.868 |

| Egoistic Value Orientation (EVO) | EVO1 EVO2 EVO3 |

0.913 0.883 0.771 |

0.826 | 0.674 | 0.874 |

| Table 4 Discriminant Validity – Apple I-Phone |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | EVO | BKP | PQ | ES | |

| EVO | 0.874 | 0.708 | 0.160 | 0.119 | 0.841 | |||

| BKP | 0.909 | 0.666 | 0.527 | 0.280 | 0.400 | 0.816 | ||

| PQ | 0.740 | 0.588 | 0.527 | 0.385 | 0.355 | 0.726 | 0.767 | |

| ES | 0.868 | 0.688 | 0.503 | 0.242 | 0.267 | 0.390 | 0.709 | 0.829 |

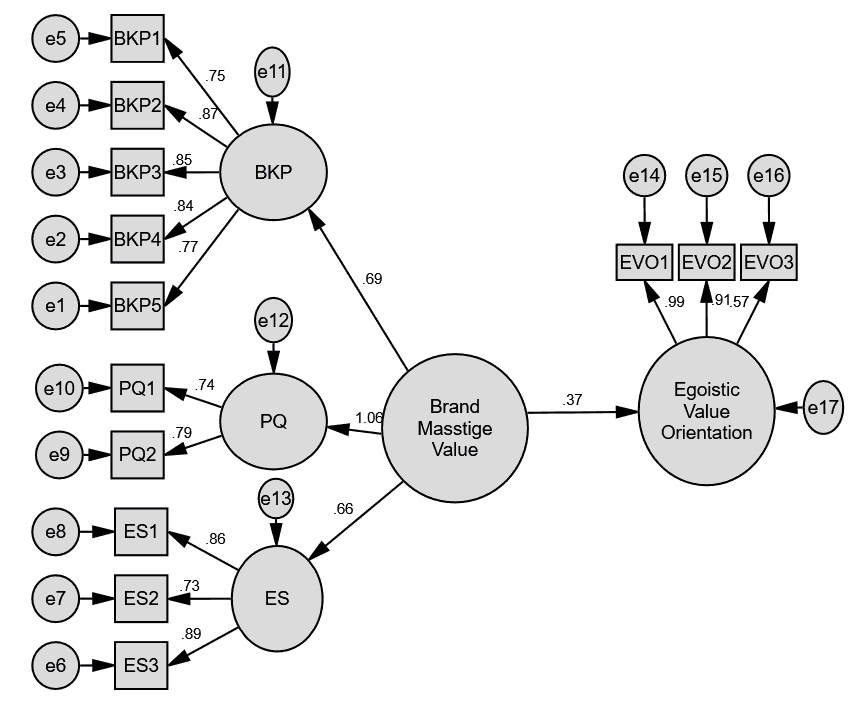

Structural Equation Modelling

The influence of brand masstige value on customer egoistic value orientation was studied using structural equation modelling. Results (Figure 1) show the standardised beta coefficient value (β)=0.37, p<0.05 (at 95 percent confidence level) indicating that the brand’s masstige value has a positive and significant impact on the egoistic value orientation of the customer while considering purchase of Apple i-phone (H2a is accepted). This means that the purchase of an Apple iPhone shall meet a consumer's ego needs (as a significant and positive egoistic value orientation is developed). A check on the model fit revealed the following values. Chi-square=107.587, df=62, CMIN/df=1.735, GFI=0.873, AGFI=0.814, CFI=0.947, RMSEA=0.084 (all within acceptable limits as per Hair et al., 2010; Baumgarther & Homburg, 1996). This means that our model is validated.

Figure 1: Impact of Masstige Value of Apple’s I-Phone on Egoistic Value Orientation of a Consumer in the Indian Market

Study 2: Impact of Samsung Smartphone’s Masstige Value on the Egoistic Value Orientation of the Consumer while Considering Purchase of the Brand

Results of Exploratory Factor Analysis

The Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) test result was 0.762, which is considered satisfactory (Kaiser, 1974). The findings of the principal component rotated matrix confirmed the construct validity of the constructs. The factor loadings are shown in Table 5. The total variance explained was 83.46 percent, which is greater than the required 50% criterion.

Validity and Reliability Analysis

The reliability of the constructs was determined using Cronbach's alpha (Nunnally, 1978). Confirmatory Factor Analysis was performed to assess the convergent and discriminant validity of our constructs (CFA). From Table 5 it can be seen that α>0.7, AVE>0.5, and α >AVE. Thus, convergent validity is established for the constructs (Hair et al., 2010). Also, as AVE>MSV and AVE>ASV (Table 6), discriminant validity of the constructs is also established (Hair et al., 2010).

| Table 5 Reliability and Convergent Validity – Samsung Smartphone |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loadings |

Cronbach Alpha (α) | AVE | Composite Reliability (CR) |

| Brand Knowledge and Prestige (BKP) | BKP1 BKP2 BKP3 BKP4 BKP5 |

0.745 0.902 0.903 0.916 0.765 |

0.903 | 0.699 | 0.924 |

| Perceived Quality (PQ) | PQ1 PQ2 |

0.822 0.839 |

0.973 | 0.947 | 0.973 |

| Excitement and Status (ES) | ES1 ES2 ES3 |

0.915 0.885 0.869 |

0.920 | 0.796 | 0.923 |

| Egoistic Value Orientation (EVO) | EVO1 EVO2 EVO3 |

0.952 0.943 0.687 |

0.759 | 0.651 | 0.865 |

| Table 6 Discriminant Validity– Samsung Smartphone |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | EVO | BKP | PQ | ES | |

| EVO | 0.865 | 0.696 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.834 | |||

| BKP | 0.924 | 0.712 | 0.162 | 0.100 | 0.093 | 0.844 | ||

| PQ | 0.973 | 0.947 | 0.370 | 0.181 | 0.100 | 0.403 | 0.973 | |

| ES | 0.923 | 0.799 | 0.370 | 0.170 | 0.100 | 0.360 | 0.608 | 0.894 |

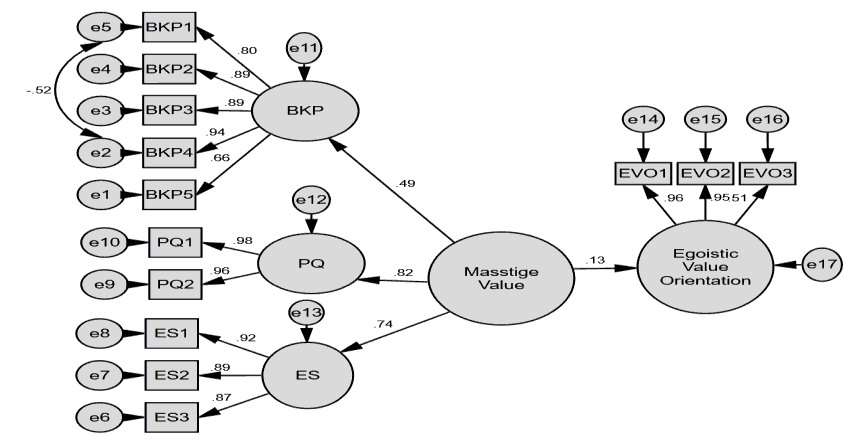

Structural Equation Modelling

The impact of brand masstige value on customer egoistic value orientation was investigated using structural equation modelling. The standardised beta coefficient value (β)=0.13, p=0.227 (at 95% confidence level) indicates that the brand's masstige value has no significant influence on the customer's egoistic value orientation when contemplating purchasing a Samsung smartphone (Figure 2). This means that the purchase of Samsung smartphone by a consumer in the Indian market will not satisfy the customer’s ego needs (H2b is rejected), as there was no significant impact of the masstige value of the brand on the egoistic value orientation of the consumer. The following values were discovered when the model fit was checked. Chi-square=107.587, df=62, CMIN/df=1.735, GFI=0.873, AGFI=0.814, CFI=0.947, RMSEA=0.084 (all within acceptable limits as per Hair et al., 2010; Baumgarther & Homburg, 1996). This indicates that our model has been validated.

Figure 2: Impact of Masstige Value of Samsung Smartphone on Egoistic Value Orientation of a Consumer in the Indian Market

Discussion

Our research examines two smartphone brands (Apple and Samsung) in order to determine their masstige value in the Indian market. In order to better understand customer behaviour while purchasing high-end items, our research also investigates a consumer's egoistic value orientation in connection to the purchase of masstige brands.

Paul (2018) expanded the utility of Mass Mean Index (MMI), which had previously been used only in the context of high-premium brands, to include popular brands that are aimed at both high- and middle-income consumers. The study used the Masstige Mean Score Scale (MMSS) to determine the masstige value of Apple i-Phone and Samsung Smartphone in the Indian market. This was accomplished by using Masstige Mean Index developed by Paul (2018) to calculate the masstige value of the respective brands.

According to our MMI analysis, the Apple i-Phone (American brand) surpassed the Samsung Smartphone (Korean brand) when considering their mass prestige value in the Indian market. The concept of masstige marketing lays down that consumers will pay a premium for luxury models from these manufacturers, as well as for product models designed for the middle income group of consumers, if they have a higher MMI.

Our findings also suggest that the Apple iPhone has a favourable and considerable influence on people's egoistic value orientation. This means that when a customer considers buying an Apple iPhone, his or her ego needs are met, as a significant and positive egoistic value orientation is developed due to masstige value of the brand. However, we see a contrasting picture in the instance of the Samsung smartphone, when masstige marketing tactics were shown to be unsuccessful in terms of influencing customers' egoistic value orientation. This is because our hypothesis H2b was rejected as the standardised beta coefficient was determined to be non-significant.

In case of luxury products, the success of a brand depends on the effective designing of product strategies along with coordinated decisions in distribution and promotion areas. Price is not a significant factor here as a luxury brand consumer buys the luxury brand because of the status attached to it. However, while designing a masstige marketing strategy, downward brand extension strategy is followed to attract the middle-income segment of the market. Thus, product designing, brand positioning and promotion decisions become important (Paul, 2018).

Our study suggests that businesses must think intelligently about their marketing tactics, particularly when attempting to reach middle-income consumers through downward brand extension. For instance, how thin can you go on the price? This is an important area, if managed incorrectly, might have a detrimental impact on the brand's masstige value. Could this be the reason why Samsung isn't seen as a status symbol, whose purchase will satisfy Indian buyers' ego needs? Is it true that offering low-cost models to lower-middle-class customers lowers a brand's masstige value? These are some of the key questions brand managers should consider when developing a masstige strategy, and can be undertaken by researchers as a study area.

Limitations and Future Research

Our research is limited in scope because it only looks at two smartphone brands in the Indian market. However, future research in this area has a lot of potential because the work done in this study could assist researchers extend a number of theoretical frameworks and measurements in the area of masstige marketing. In addition, the study's scope is not restricted to smartphone manufacturers. Researchers may extend the research in other areas which may include measuring the masstige value of prestige brands in sectors such as automobiles, laptops, TVs, and luxury handbags in various nations, particularly in emerging markets.

There are also opportunities to do cross-national research. The sample can also come from people from diverse areas, nations, and religious backgrounds. Researchers should also consider expanding the scope of the masstige marketing paradigm.

Conclusion

In order to calculate their masstige value in the Indian market, our study looks at two brands in the smartphone product category. In order to better explain customer behaviour while purchasing these high-end goods, our study also proposes the unique concept of a consumer's egoistic value orientation in relation to purchase of masstige brands. Thus, we build on prior masstige marketing research by assessing the masstige value of two top-of-mind smartphone brands in a developing nation and investigating the link between a brand's mass prestige value and a customer's egoistic value orientation when purchasing a smartphone brand.

As far as developing masstige value in the Indian market is concerned, the Apple i-Phone (American brand) has outperformed the Samsung Smartphone (Korean brand) according to our MMI analysis. Additionally, our data imply that the Apple iPhone has a positive and significant impact on people's egoistic value orientation. In the case of the Samsung smartphone, on the other hand, masstige marketing strategies were proved to be ineffective in terms of influencing buyers' egoistic value orientation. The study's findings are significant in terms of adding to the sparse current literature in the field of masstige marketing.

References

- Baumgarther, H., & Homburg, C. (1996). Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13(2), 139-161.

- De Groot, J.I.M., & Steg, L. (2008). Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environment and Behavior, 40(3), 330–354.

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, (7th edition). Prentice-Hall, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA

- Han, J.H., & Lee, E. (2016). The different roles of altruistic, biospheric, and egoistic value orientations in predicting customers’ behavioral intentions toward green restaurants. International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 30(10), 71-81.

- Kaiser, H.F., & Rice, J. (1974). Little Jiffy Mark IV. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 34(1), 111-17.

- Kapferer, J.N., & Bastien, V. (2009). The specificity of luxury management: turning marketing upside down. Journal of Brand Management, 16(5/6), 311–322.

- Keller, K.L., & Lehmann, D. (2003). How do brands create value? Marketing Management, 3, 27-31.

- Kumar, A., & Paul, J. (2018). Mass prestige value and competition between American versus Asian laptop brands in an emerging market: theory and evidence. International Business Review, 27(5), 969-981.

- Mohd Yasin, N., Nasser N.M., & Mohamad, O. (2007). Does image of country-of-origin matter to brand equity? The Journal of Product and Brand Management, 16(1), 38-48.

- Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Assessment of Reliability. In: Psychometric Theory, (2nd edition). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Paul, J. (2015). Masstige marketing redefined and mapped: Introducing a pyramid model and MMS measure. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(5), 691-706.

- Paul, J. (2018). Masstige model and measure for brand management. European Management Journal, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.07.003

- Paul, J. (2018). Toward a ‘masstige’ theory and strategy for marketing. European Journal of International Management, 12(5/6), 722-745. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2018.10012543.

- Riefler, P. (2012). Why consumers do (not) like global brands: The role of globalization attitude, GCO and global brand origin. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(1), 25–34.

- Roper, S., Caruana, R., Medway, D., & Murphy, P. (2013). Constructing luxury brands: Exploring the role of consumer discourse. European Journal of Marketing, 47(3/4), 375 – 400.

- Roth, K.P.Z., Diamantopoulos, A., & Montesinos, M.A. (2008). Home country image, country brand equity and consumers’ product preferences: An empirical study. Management International Review, 48(5), 577–602.

- Schwartz, S.H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1-65). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Silverstein, M.J., & Fiske, N. (2003). Luxury for the Masses. Harvard Business School Press, USA.

- Steenkamp, J.B.E., & de Jong, M.G. (2010). A global investigation into the constellation of consumer attitudes toward global and local products. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 18–40.

- Steenkamp, J.B.E., Batra, R., & Alden, D.L. (2003). How perceived brand globalness creates brand value. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(1), 53–65

- Stern, P.C. (2000). Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407-424

- Truong, Y., McColl, R., & Kitchen, P.J. (2009). New luxury brand positioning and the emergence of masstige brands. Journal of Brand Management, 16(5/6), 375–382.