Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 4S

Media addiction of youth audience

Lesia Horodenko, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv

Yevhen Tsymbalenko, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv

Citation Information: Horodenko, L., & Tsymbalenko, Y. (2022). Media addiction of youth audience. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(S4), 1-13.

Abstract

The article studies the media addiction in the professional (journalistic) youth environment. The set objective was reached through the summarising, systematising, analysis and commenting of the longterm experiment (4 years) results on the media addiction studies in youth homogeneous audience (4-year-students during the period 2016-2019). The research was conducted in parallel and sequentially, consisting of pre-experimental stage (initial testing), the experiment itself, and post-experimental stages – retesting and writing essays-reflections. The core of the experiment was a kind of challenge of “24 hours of digital information freedom” when the respondents were required not to use any information and communication digital gadgets. The results of the experiments and surveys were processed and discussed during the colloquiums directly with the participants of the experiment as well as with the coordinators and guarantors of educational programs in Journalism. As the research result, a series of summary tables are presented; equally interesting and relevant are participants' reflections on self-analysis of their own digital addiction (depending on the constant – often unconscious – use of digital gadgets), dependence on communication through social networks, messengers as well as the desire for self-improvement and self-control of their own media activity. In addition, we have encountered a problem with the use of prohibited social networks in Ukraine. Although the statistics of the last year experiment showed a decrease in the number of active users of such social networks, it is yet too soon to talk about not considering them.

Keywords:

Social Communications, Media, Media Addiction, Digital Communication,Social Networks

Introduction

Recently, in the media space of Ukraine (this is a worldwide trend as well) there is a tendency to entertain and provocative. Modern media projects try to keep the audience by scandals, entertainment, intimidation, intrigue, media wars and more. Such tabloid-colored, open-ended media products encourage the audience to be constantly interested in the plot development and follow-ups. Moreover, media content is easily adaptable to different media and the person is in a kind of media vacuum – the environment formed by opinion leaders and massifiers. Information and social “bubbles” define systems of stereotypical perception and behavior, and also stimulate a kind of “herd”: “like friends' posts in the morning”, “ make coffee and croissant selfie for breakfast”, “comment on the way to the institute or to work later”, “share the challenge” and many other important communication activities throughout the day. But the main functions of media are informational and educational, which include intellectual development of the audience, expansion of outlook, scientific and cultural enlightenment, formation of a mature, value-conscious nation. At the same time, despite the content or idea which media are trying to transmit to the audience, we become hostages to various media. Smartphones, TV, computers, tablets, iPods and iPads, Xboxes or any other gaming console, smart home devices – we are surrounded by them and often do not realize our addiction. Therefore, it becomes relevant to study and understand not only the content, its form, the means and technologies of its dissemination, but also the likely consequential changes in the information consumer's behavior and the formation of dependencies on the media, which is an important component of media education and media literacy.

As the international practice shows, the problems of media education, media literacy, media dependence or mediation are global and need urgent attention from both government agencies and media organizations themselves. UNESCO recommendations, a range of programs and doctrines emphasize the need to provide equal access to information and knowledge for the entire population of the world (UNESCO, 2019). In addition, media education programs help the youth audience learn complex topics from the school program, offer an alternative explanation of the subject, more vivid illustration to the lesson, teach to think critically and not to trust all information received by various media channels (UNESCO, 2019). In quarantine conditions, or distance learning, widely spread by the coronavirus, video tutorials and a variety of distance education programs have virtually replaced teacher/professor interpersonal communication with pupils/students or turned it into mediated communication (media communication).

Equally relevant is the establishment of cause and effect relations that stimulate mediation and the immutation of the society, destroy cultural values systems, create consumer society (consumerization) and appear in mass audiences under the influence of media products. We are convinced that only knowing and understanding the modern mass audience, its information priorities and the tendency to use certain media regularly, and, based of this forecast, we can propose and develop comprehensive measures for the implementation of media education programs to improve media literacy level of the society.

The aim of the article is to study media dependence in a professional (journalistic) youth environment.

The aim considers solving the following tasks:

• To conduct a long-term experiment in a homogeneous environment to define the level of media dependence in the youth audience;

• To find out the level of youth’s readiness for critical perception of media information and available identifiers of media dependence of this age group of mass media audience.

Object: Media Addiction

Subject: The components which shape the media interdependence of the youth audience. The theoretic background of our research were the works of such researchers as H. Onkovych (Onkovych, 2010), L. Naidionova (Naidionova, 2008; Naidionova, 2012), the developments of the Academy of Ukrainian Press (Ivanov & Voloshenuk, 2012). Nevertheless, we used electronic sources to gain a deeper understanding of the issue. Basic theoretical developments in the field of media education were also studied, including the works by L. Masterman (Masterman, 1997), D. Buckingham (Buckingham, 2001). The special place is given to the works of the Ukrainian scholars: V. Ivanov (Ivanov & Voloshenuk, 2012), V. Rizun (Rizun, 2013), N. Zrazhevska (Zrazhevska, 2012; Zrazhevska, 2014), T. Krainikova (Krainikova, 2014), H. Onkovych (Onkovych, 2010), etc.

The issue of media culture and media consumering, the formations of the media society culture at the doctor level were discussed by N. Zrazhevska (Zrazhevska, 2012; Zrazhevska, 2014) and T. Krainikova (Krainikova, 2014), many scientific ideas on the formation of the information society media culture are considered in the works of I. Zhylavska (Zhylavskaia, 2009), L. Masterman (Masterman, 1997), A. Novikova (Novikova, 2001), M. Skyba (Skyba, 2011), etc.

The issues of the media literacy formation for the personal development were analysed by O. Burym (Bakka et al., 2016), I. Zadorozhna (Kremen, 2008), A. Ishchenko (Ischenko, 2015, May 13), T. Kuznetsova (Kremen, 2008), A. Lytvyn (Lytvyn, 2009), O. Fedorov (Fedorov, 2010), etc.

The direct impact of the youth’s media addiction and modern digital technologies were the research objects in the works of L. Naidionova (Naidionova, 2008; Naidionova, 2012), I. Bielinska (Belins’ka, 2016), etc.

The manipulation of public opinion, the distortion of information flows, propaganda and other communication methods leading to the imbalance of the society and causing problems of facts distortion were studied by H. Pocheptsov (Pochepthov, 2008), V. Ivanov (Ivanov & Voloshenuk, 2012), O. Volosheniuk (Ivanov & Voloshenuk, 2012), L. Horodenko (Horodenko, 2012), V. Kornieiev (Kornieiev, 2014), O. Kholod (Kholod, 2012), etc. In this context, we are particularly interested in O. Kholod’s views on the processes of mutation-inmutation in the society under the influence of the media since it is the result of the presence or absence of media literacy perception, critical analysis of information flows that causes particular changes in an individual’s behavior.

Research methods. The basis of the study was the social communication approach (developed by V. Kornieiev). In addition, we relied on the theoretical foundations of communication science, journalism, pedagogy, sociology, psychology. In particular, descriptive method was used to clarify, explain the phenomena of media education, media literacy, media culture, and other topics relevant to the study. At the theoretical stage of the materials study we used methods of literature analysis, comparison, formalization. Statistical analysis has systematized data obtained from expert surveys, interviews and experiments. We used the methods of survey, content analysis, expert survey and interviewing (five experts), expert analysis (we asked the experts to comment on the results of the questionnaire) to find out the main tasks that were put in the experiment. At various stages of the research preparation, we used the methods of observation, abstracting, generalization.

During the long-term experiment, a number of empirical methods were used, including: surveys, systematic field inclusion, content analysis, statistical data processing, forecasting. The methodology of the experiment are described in detail in the article.

The phenomenon of media dependence is not new to the theory of mass communication. Back in the 1980s, it was discussed by S. Ball-Rokeach and ?. DeFleur in the article «A dependency model of mass-media effects» (Ball-Rokeach, S.J., DeFleur, M.L., 1976). Finding reasons for an individual’s media addiction has become a topic of further research, e.g. «The origins of individual media-system dependency: a sociological framework» (Ball-Rokeach, S.J., DeFleur, M.L., 1985). Media addiction becomes a problematic area of interdisciplinary character: sociologists (e.g. Patwardhan, P., Ramaprasad J., 2005), psychology (e.g. L. Naidionova (Naidionova, 2008; Naidionova, 2012), journalism scholars (e.g. H. Pocheptsov (Pochepthov, 2008), culturologists (e.g. N. Zrazhevska (Zrazhevska, 2012; Zrazhevska, 2014)) are trying to find out the cause and effect and suggest ways to overcome global media dominance in the society.

Since we do not set out to study media dependency in theoretical terms, we will not dwell on detailed and in-depth commentary on the features, positions, historical stages, and other elements of the phenomenon, and emphasize on the interpretation which is most appropriate for our study: “Media addiction is a disorder of volitional behavior, manifested in the abuse of the media (excessive consumption of media products, decreased self-regulation, narrowing of interests only to the sphere of media with deterioration in other spheres of life, etc.)” (Litostanskyi, 2014).

The issues we focus on are wider and cover the entire digital media space, from the “background” listening to radio or music channels to in-depth immersion in virtual content through a variety of digital gadgets.

Portioned and planned information allows you to manage the society without social stress and explosions. We have repeatedly discussed it in our previous works (e.g., (Tsymbalenko & Horodenko, 2016)): the information flaw, which which impacts the population. The reason for the overproduction of news are both extraordinary events and ordinary events, without any information load, the recordings of cats, dogs and someone having breakfast in the morning. All these information flows form a person’s perception of the world, often creating illusion realities. The perception of information by a person, their interest in the further generation of information flows, pragmatic approaches to understanding what you read and what you write about, lay the foundations of the society’s media literacy as a whole.

In order to understand how to improve the society’s media literacy, one must first study this society with its aspirations and priorities. For four years, with the help and support of the Scientific Department of the Institute of Journalism at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (e.g., Y. Tsymbalenko & L. Horodenko) The scholars studied the youth’s addiction to the communication gadgets, networks and media addiction as a whole. The task for the audience has been the same for four years. Therefore, we can talk about temporal systematicity in the results of the experiment.

Another interesting thing in our study are the approaches to social media dependency analysis published by Chinese scholars in the journal “Cyber Psyhology”. Similar to our study, that research is built on several stages, within which the dependence of the audience on social media as well as mediation and the cause and effect components were studied. The scholars summarize: “Our results show that social media dependence was associated with a decrease in mental health, a partial decrease in people’s self-esteem, and a reverse indirect self-esteem activity with mental health and a dependency on social media as a variable result was not essential” (Hou et al., 2019).

However, unlike the research “Social Media Addiction: Influence, Mediation, and Intervention” (Hou et al., 2019), this article focuses primarily on communication aspects, and the psychological elements discussed in respondents' summaries, their self-analysis and self-identification were additional “bonuses” that made the nature of the scientific problem more widely disclosed. We have also studied the issue more extensively, since social media serve only one link in the global digital media space, and within our experiment, we were tasked with complete refusal of digital and media reality for a certain period of time.

Both the integration of teens into the social networking space and dependency systems in this age category are discussed by Griffiths, M.D. and Kuss, D.J.. With the reference to the research of their predecessors, they say: “Teenagers particularly appear to have subscribed to the cultural norm of continual online networking. They create virtual spaces which serve their need to belong, as there appear to be increasingly limited options of analogous physical spaces due to parents’ safety concerns” (Griffiths & Kuss, 2017). Thus, they tend to believe that high levels of involvement of young people in social networking communications are shaped by parental control and real-life constraints. As a result of the experiments, Griffiths, M.D. and Kuss, D.J. affirm: “Research suggests younger generations may be more at risk for developing addictive symptoms as a consequence of their SNS use, whilst perceptions of SNS addiction appear to differ across generations. Younger individuals tend to view their SNS use as less problematic than their parents might, further contributing to the contention that SNS use has become a way of being and is contextual, which must be separated from the experience of actual psychopathological symptoms” (Griffiths & Kuss, 2017). In our research, it is not so important which age groups are more or less prone to addiction; however, the affirmation that young people are less likely to perceive their social media presence, as problematic resonates with the results of our study (namely, the pre-experimental polling phase when respondents do not consider themselves dependent on the digital media environment. See below for more details).

The conditions of the experiment. The participants of the experiment agreed not to use any digital media communication device, including: a laptop (or any other technical form of the computer), a TV, a telephone, a smartphone, a radio, and any other gadget for 24 hours. The experiment started at 0 hours and ended 24 hours later. Prior to the experiment, the participants were advised to warn relatives and friends not to experience the sudden disappearance of a digital communication card. At the end of the experiment, the participants were required to write an essay (but no later than 48 hours after the end) in which they had to describe their condition (primarily, psychological). There was a possibility of a digital “breakdown”, which the participant had to explain in the summary.

Quantitative indicators of the participants. The experiment was conducted annually on the 4th year of the bachelor’s degree program in Journalism at the Institute of Journalism (2016–2019). The total number of participants is 379 people. Division by years (Table 1):

| Table 1 The Quantity of the Experiment Participants |

||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Quantity of the Participants | Percentage of Female/Male Audience |

| 2016 | 105 | 81/19 |

| 2017 | 96 | 82/18 |

| 2018 | 78 | 79/21 |

| 2019 | 100 | 86/14 |

Unfortunately, there is a gender roll at the Institute of Journalism, the number of female students significantly exceeds the number of male students. That is why we emphasize this.

In terms of age, it is an audience of 20–21 years with a slight shift to the younger side (less than 2%) and a slightly larger increase to the older side (5%). That means that in the age sense the whole audience was homogeneous during all four years of the experiment.

The methodology of the experiment. To prepare the first phase of the experiment, we used theoretical methods that helped us to develop the questionnaire and to predict the procedures for conducting the experiment and further processing of the data obtained.

The purpose of our study and the the level of the topic development determine the consistent and logical use of such empirical (survey, observation), description and theoretical methods (analysis, synthesis, induction, deduction, monographic method). At the final stage of the experiment, we used generalization.

In order to solve the main tasks of the experiment, we used the methods of survey, content analysis, expert interviewing and interviewing (five experts were interviewed), expert analysis (we asked the experts to comment on the results of the questionnaire). At different stages of preparation and conduct of the experiment and processing of data, we used the methods of observation, abstraction, generalization.

During the long-term experiment, a number of empirical methods were used, including: surveys, systematic field inclusion method, content analysis, statistical data processing, forecasting.

During the work, the use of synthesis and induction methods, based on the specific facts and characteristics established during the empirical studies, allowed us to form an overall picture.

The analysis of the obtained data and its generalization gave the basis for providing recommendations on the use of communication technologies of the “outstripping” group in order to minimize the communication risks related to potential inclinations of the mass audience before the sensational facts are accepted without attempting to analyze or verify the data.

The surveys, disseminated during personal meetings with respondents, formed an idea of potential risks of media dependence, respondents’ interest in unconscious use of communication technologies when interacting on social networks, and writing posts or social media blogs), sources of information about them, channels of communication prefered by young people in the communication process.

In addition, we used the systematic field inclusion method, conducting such experiment personally prior to the experiment in the group each year. We recorded the participants’ feelings in the diary and compared them with the data collected from the group.

The methods and the stages of the experiment. The experiment had a complex, multi-level structure that extended over time. However, the procedure for conducting the experiment was carried out annually by the same mechanism. The survey contained the same questions, with the exception of 2017.

In order to find out, confirm, or disproof the basic hypothesis of the study regarding the unconscious use of communication gadgets, we conducted the survey at several stages:

Stage 1. The development of the survey, consulting with specialists of the Institute of Journalism on the preparation of empirical data and methodology for the field research.

Stage 2. The conduction of the four-waves survey including:

2.1. Pre-defining of media addiction awareness in the audience;

2.2. Sequential defining of media addiction awareness in the audience.

Stage 3. Parallel systematic field inclusion for annual comparison of mass surveys results.

Stage 4. Processing the survey results using content analysis.

Stage 5. Processing the essays based of the experiment results “24 hours of digital freedom”.

We have already mentioned the long terms of the experiment. Important questions that enables the understanding of the audience’s media preferences were those in which the specificity of communication in social networks was revealed. As in May 2017, in accordance with the Presidential Decree # 133/2017, several hundred of Russian companies, including media and telecommunications companies, were subject to economic sanctions. As a result, Ukrainian Internet service providers have restricted users from accessing Russian social networks VKontakte, Odnoklassniki and the websites Yandex, Mail.ru (Ofissial Websitte of the President of Ukraine, 2017). Considering this prohibition, we decided to add the following question: “Do you continue to use your account in the social network VKontakte after the official prohibition?” with such options:

1) Yes, I use my VKontakte account every day;

2) I check my account from time to time;

3) I deleted my VKontakte account;

4) I did not have VKontakte account.

As a result of the summary data, it turned out that 80% of respondents continue to regularly check their VKontakte accounts.

Before the experiment conduction, all the participants were asked: “How strongly do you consider yourself media addicted on the scale from 1 to 5, where

A. I am not media addicted;

B. I am not media addicted but I understand the necessity of the media and media technologies use;

C. I realise the necessity of media in my life;

D. I consider media an important component of my everyday life;

E. I realise my media addiction.

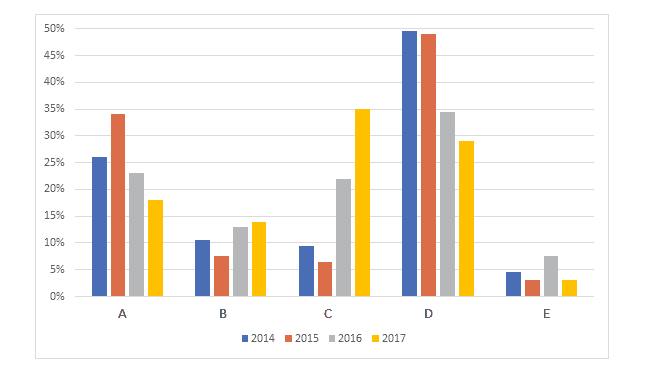

To systematize the data we have received over four years, we have introduced a categorical apparatus consisting of two parts. For example, A–2016 means: the category of 2016 participants who answered the question “I am not media addicted”.

| Table 2 The Results of the Pre-Experimental Poll.* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ? | B | C | D | E | |

| 2016 | 27 (26%) | 11 (10,5%) | 10 (9,5%) | 52 (49,5%) | 5 (4.5%) |

| 2017 | 33 (34%) | 7 (7,5%) | 6 (6,5%) | 47 (49%) | 3 (3%) |

| 2018 | 18 (23%) | 10 (13%) | 17 (22%) | 27 (34,5%) | 6 (7,5%) |

| 2019 | 18 (18%) | 14 (14%) | 36 (35%) | 29 (29%) | 3 (3%) |

* The indicators are presented in quantitative and percentage terms.

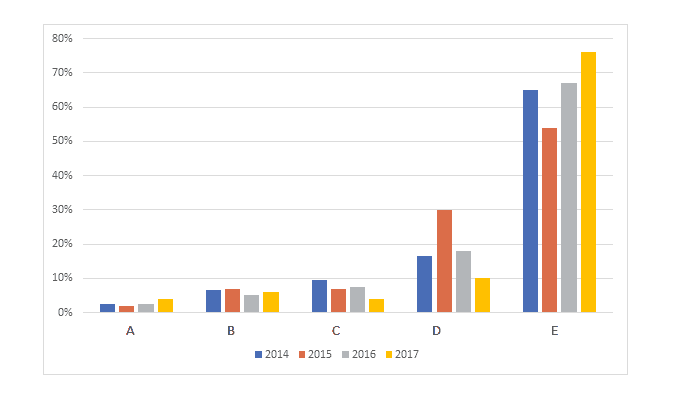

At the end of the experiment, the participants were asked the same question. As predicted, before and after results differed dramatically.

| Table 3 The Results of the Post-Experimental Poll.* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ? | B | C | D | E | |

| 2016 | 3 (2,5%) | 7 (6,5%) | 10 (9,5%) | 17 (16,5%) | 68 (65%) |

| 2017 | 2 (2%) | 7 (7%) | 7 (7%) | 29 (30%) | 51 (54%) |

| 2018 | 2 (2,5%) | 4 (5%) | 6 (7,5%) | 14 (18%) | 52 (67%) |

| 2019 | 4 (4%) | 6 (6%) | 4 (4%) | 10 (10%) | 76 (76%) |

* The indicators are presented in quantitative and percentage terms.

We see the usefulness of our experiment, at least in the way the participants looked at themselves from the other side and were able to independently understand how dependent (or not) they were on the media. The findings of the experiment give us the reason to state the high level of media education and media literacy of the surveyed groups, their willingness to self-improve and help their loved ones understand how immersed they are in the media and communication environment.

It is clear that no results will change the attitude of the mass audience to the Internet, television, communication in the social networks. We are all media dependent. And only our conscious desire and conscious actions will help each of us to develop personal media literacy.

From the data in Table 2 and Diagram 1, we can conclude that the experiment participants did not consider themselves dependent on media and communication technologies. This also resulted from the survey’s answer to the following question: Are you sure you can fulfill all the experimental conditions?

At this stage, we got the clear answer “I cannot fulfil the conditions because…” from 17 participants (category E–2016 – E–2019) with two different options:

1) I work that is why I have to stay connected 24/7 – 12 answers;

2) Because of family issues (without details) – 5 answers.

Moreover, the survey contained the questions which systematised and gave some hints to the participants. The answers to these questions were typical but enabled additional commenting, used quite rarely.

Questions: “How often do you watch TV?”, “How often do you listen to the radio?”, “How often do you read the newspapers?”, “How often do you read books? (excluding educational literature)”, “ How often do you “surf” the Internet?”, “How often you check your social networks accounts?”, “How often do you use your e-mail?”.

Answers:

1) Every day;

2) Often (once per 2–3 days);

3) Sometimes (once per week);

4) Not often (less than once per week).

This group of questions partly goes beyond the basic conditions of the experiment, but thanks to them, we can structure participants’ media preferences and media priorities, as well as identify the sources of greatest influence in today’s youth audience (Table 4).

| Table 4 The Average Use of Media Types in the Youth Audience (%) |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every day | Often | Sometimes | Not often | |||||||||||||

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| How often do you watch TV? | 50 | 45 | 55 | 60 | 25 | 25 | 30 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 20 |

| How often do you listen to the radio? | 90 | 93 | 95 | 90 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| How often do you read the newspapers? | 10 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 20 | 40 | 10 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 35 | 35 | 45 | 40 |

| How often do you read books? (paper) | 15 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 35 | 35 | 25 | 30 | 30 | 25 | 35 | 35 |

| How often do you “surf” the Internet? | 95 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| How often you check your social networks accounts? | 87 | 90 | 90 | 82 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| How often do you use your e-mail? | 70 | 85 | 80 | 65 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 20 |

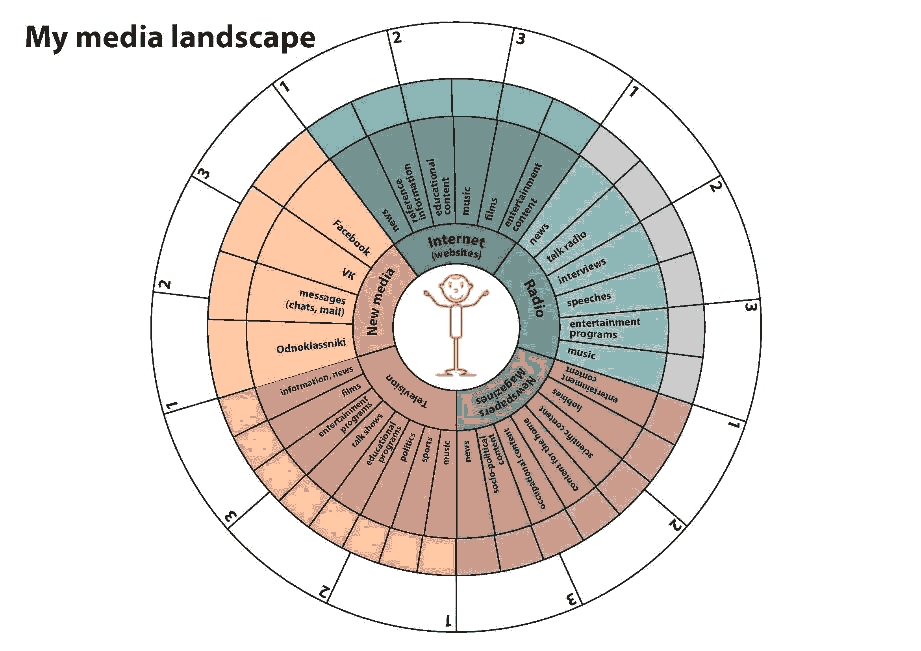

In order to define the media priorities in the data systematisation, we used the media map “Personal Media Space”, developed by Internews Ukraine for the media education projects (Academy of Ukrainian Press, 2016). We emphasize: we did not hand out the samples of media map to our respondents and did not discussed all media, mentioned in the scheme; we used it as the form for the data systematisation, broadening by years (Picture 3).

The results showed that 80% of the respondents do not watch TV AT ALL (over the last 3 months at the time of each stage of the survey), but instead regularly watch movies and series at convenient times on YouTube channels or online video players. Mainly news (the results ranged from 70% to 85%) is received through the websites that are individually identified as credible. As we set the task to determine the amount of time that respondents spend daily for certain media resources, as well as the total value of media use, 8% of respondents exceeded this indicator over 24 hours. Thus, a respondent simultaneously listens to the background music in the earphones, scrolls social networks on their phone, works on a computer, etc. In one of the essays we find the following description of the “classic” routine: “ I wake up with the alarm on the smartphone and scroll the news feed at once, like (sometimes unconsciously) friends’ posts, answer private messages. I get up and connect the speaker to the phone, turn on the music. While having breakfast, I scroll social networks. I turn on my computer and start getting ready for classes. At this point, I put my phone to silent mode as I will be distracted by Telegram, WhatsApp or other messages. On my way to the Institute, I listen to music and read e-books. During the classes, I often scroll through news feeds and social networks. As a rule, I record the lectures on a voice recorder (I later listen to them but not all of them). On my way back, I listen to music and chat with friends in messengers. In the evening, I watch TV shows on the tablet, scroll news feeds, social networking (the essay on the experiment results).

One more block of questions in the survey, which were given for obtaining general information during the pre-experimental survey, was directly related to the media literacy of the audience. These were the questions that defined the respondents’ overall level of trust to social media posts and, as a consequence, their involvement, conscious or unconscious, in the mass communication process with the introduction of communication technologies.

Do you analyse the messages texts in social networks?

Yes, often

Sometimes, if I am interested in the topic.

No, I do not perceive the information from the social networks as “information background”.

Other __________________________________________________

Do you check the information, read in the messages (posts) in social networks?

Yes, often.

Sometimes, if I am interested in the topic.

No, I consider this information a fact.

Other __________________________________________________

Do you trust the information, shared by your friends in social networks?

Yes, often.

Sometimes, if I am interested in the topic.

No, I consider the information from friends a fact.

Other __________________________________________________

Are you distracted by the social networks messages (posts), working with predefined thematic information blocks?

Yes, very often.

Yes, often.

Sometimes, if I am interested in the title or the abstract.

No, I try not to pay attention to the information not connected to the topic.

Other ______________________________________________________

The results showed a fairly high level of media literacy among the students of the Institute of Journalism, because in their answers they determined their potential desire to check the facts as well as the tendency not to trust information from friends. Because the annual error in responses was minor, we provide data summary (379 participants) for the entire experiment period (Table 5).

| Table 5 Respondents’ Inclination to Fact-Checking (Option “Yes, Often”), %* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2018 | |

| Do you analyse the messages texts in social networks? | 84 | 87 | 81 | 78 |

| Do you check the information, read in the messages (posts) in social networks? | 82 | 38 | 57 | 69 |

| Do you trust the information, shared by your friends in social networks? | 39 | 45 | 42 | 37 |

| Are you distracted by the social networks messages (posts), working with predefined thematic information blocks? | 71 | 76 | 75 | 84 |

* We must consider that the experiment was conducted among the future media professionals, thus, the fact-checking is one of the key tasks of the profession. We emphasize that we are not able to conclude on the potential of the whole youth audience for media critical-thinking.

The tendency towards critical media thinking and the willingness to control one’s own media dependence can also be traced in the essay and the post-experimental survey. The readiness to limit the time spent on social networks was expressed by 75% of participants; and only 10% said it was extremely undesirable and even unrealistic in their case. It should be noted that these respondents showed weakness and despite the announced confidence in the ease of completing the tasks, they still “broke down” and started using digital gadgets before the experiment ended.

Interesting comments were found in the surveys about support and misunderstanding of the surrounding conditions of the experiment from “my parents decided to spend time with me without internet and television” to “my roommates specifically provoked me with loud statements about incredible stories on Instagram or news”. The process of internal struggle is reflected in a large number of essays, such as: “I was worried by the end of the day that something drastic had happened in the world and I had missed it.” Alongside, there were many optimistic statements that “there was time to clean the room”; “finally you can bake a pie for which all three years did not have enough time”; “walking around the city is wonderful” and others. Significant in this context is the comment of one of the participants, who for the day reworked everything she could think of, and in the evening went to visit friends for tea party. After two hours of face-to-face communication, without phones, social networks, the girl concluded: “It turns out my groupmates are interesting girls.”

Conclusion

In the society, stereotypes are formed based on the importance of events. However, under some conditions, no one will know anything about it. And in the first place it depends on the media. If journalists decide that a group meeting does not entail anything interesting, only participants, their close relatives and friends will know about it. If an issue occurs, say in 1953, among the graduates, well-known scholars, politicians, and journalists, then such ordinary event is of interest to the mass media and will be covered in media. Media used to function according to this scheme. Now, almost every participant of the meeting will post information about it on their pages on social networks; web-like, the information can multiply and be known by many people for whom this information is of no interest.

Social networks nowadays have become a powerful medium of communication with the characteristics of mass and individual communication. Most Internet and mobile users take social networks for granted. Instead, the mass media, advertisers, political technologists, and other communication professionals consider social networks a powerful tool for promoting material and information products and services. In addition, social networks are absolutely “fertile soil” for conducting information hybrid wars due to the relatively low media literacy of Internet users, the spontaneity of information flows dissemination, the clickability of messages perception, etc.

As a result of a long-term experiment, we have identified a number of persistent trends in the youth audience media addiction. In particular, the benefits of media communication have been explored, such as surfing the Internet and viewing messages on various social networks. Also, printed press neglect has been identified, giving appropriate signals to media education professionals when selecting effective channels of information dissemination. There is also a tendency to troll among young people and a willingness to accept unverified information, shared by friends or acquaintances on their social media pages.

We do not claim the maximum reliability of the obtained results. We also admit the errors. However, as a result of long-term surveys and experiments, we can draw some conclusions regarding the media dependency of young people, their tendency to perceive the communication technologies applied to them in the mass audience of social networks and social media, and conscious/unconscious perception/aversion of communication technologies, disseminated through journalistic and user-generated content on social networks and social media.

The most unfortunate conclusion, besides the tendency to media addiction, concerns the VKontakte network. Of course, there is much discussion about the feasibility or inappropriateness, timeliness or its lack in the steps, taken by the government, but we have found that young people continue to be “active” in this social network. Thus, we are able to define the neglect of the legislation and low national awareness as well as their own actions awareness. We urge media education professionals to take into account the metrics we have presented, and emphasize the importance of social networks for personality formation in the implementation of new media literacy programs.

References

Academy of Ukrainian Press. (2016). Protect yourself from the flood of information.

Bakka, T., Burim, O., Volosheniuk, O., Yevtushenko, R., Meleshchenko, T., Mokrohuz, O. (2016). Media literacy and critical thinking in social studies lessons: Teacher's Guide. Kyiv: AUP [in Ukrainian].

Ball-Rokeach, S.J. (1985). The origins of individual media-system dependency: A sociological framework. Communication Research, 4, 485-510.M

Ball-Rokeach, S.J., & DeFleur, M.L. (1976). A dependency model of mass-media effects. Communication Research, 1, 3-21.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Belins’ka, I. (2016). Educational influence of a developing films on a preschool children. Moral and ethical discourse of the modern mass media in the nowadays challenges coordinates [Conference papers] (pp. 118-122). Kyiv: Milenium [in Ukrainian].

Buckingham, D. (2001). Media education. A global strategy for development. UNESCO.

Fedorov, ?. (2010). Terminology dictionary of media education, media pedagogy, media literacy, media competences. Taganrog: Taganrog State Pedagogical Institute [in Russian].

Griffiths, M.D., & Kuss, D.J. (2017). Adolescent social media addiction (revisited). Education and Health, 29, 49-52.

Horodenko, L. (2012). Network Communication: Theories, models, technologies. Doctoral dissertation, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv [in Ukrainian].

Hou, Y., Xiong, D., Jiang, T., Song, L., & Wang, Q. (2019). Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychology. Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13(1).

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Ischenko, A.Y. (2015). Medialiteracy as a factor for improving the education quality and an instrument of combating humanitarian aggression.

Ivanov, V. (2019). Practice book of medialiteracy for multiplicators. Kyiv: AUP.

Ivanov, V., & Voloshenuk, O. (2012). Mediaeducation and medialiteracy: The textbook. Kyiv: Tsentr Vilnoi Presy.

Kholod, ?. (2012). Communication technologies: Textbook. Kyiv: KyMU [in Ukrainian].

Kornieiev, V. (2014). Communication technologies as the instrument for social reality projection. Scientific Notes of the Institute of Journalism, 56, 176-181 [in Ukrainian].

Krainikova, T. (2014). Culture of media consumption in Ukraine: From Consumerism to Prosumerism. Boryspil: Luxar [in Ukrainian].

Kremen, V. (Ed.), Zadorozhna, I., & Kuznetsova, T. (2008). Medialiteracy. Kyiv: Urincom Inter [in Ukrainian].

Litostanskyi, V., Ivanov, V., Ivanova, T., Volosheniuk, O., Danylenko, V., & Melezhyk, V. (2014). Medialiteracy Basics: Curricula for 10-11 years of study in schools with Ukrainian, Russian and other National Minorities Languages of Study. Kyiv: AUP.

Lytvyn, ?. (2009). Mediaeducation tasks in specialist’s training. Naukovi zapysky Ternopilskoho natsionalnoho pedahohichnoho universytetu imeni Volodymyra Hnatiuka. Scientific Notes of Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University. Series: Pedagogy, 3, 31-37.

Masterman, L. (1997). A rationale for media education. In Kubey, R. (Ed.), Media Literacy in the Information Age: Current Perspectives, Information and Behaviour, 6, 15-68.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Naidonova, L. (2008). Media Helplessness as a Resource Disorientation in the Post-virtual World. Human in the world of information, 9-13.

Naidonova, L. (2012). Virtuality reflection is a new approach to the media and information literacy (MIL) formation. Virtual Education Space: Psychology Issue [Conference papers].

Novikova, A. (2001). Vtlsaliteracy in English Language Speaking Countries. Pedagogy, 5, 87-91.

Ofissial websitte of the president of Ukraine. (2017). The president of Ukraine Decree ?133 / 2017 "On the Decision of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine from April 28, 2017 "On the Application of Personal Special Economic and Other Restrictive Measures (Sanctions)".

Onkovych, H. (2010). Media education in Ukraine: Modern situation and development perspectives. Scientific Notes of Lesya Ukrainka Volyn National University. Series «Philology Sciences», 21, 235-239 [in Ukrainian].

Patwardhan, P., & Ramaprasad J. (2005). Internet dependency relations and online activity exposure, involvement, and satisfaction: a study of American and Indian internet users. International Communication Association; 2005 Annual Meeting [Conference papers]. New York, NY, 1-32.

Pochepthov, H., & Chukut, S. (2008). Information politics. Kyiv: Znznnia [in Ukrainian].

Rizun, V. (2013). Detection and research methodology of mass communication influence. Herald of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv: Journalism, 1 (20), 42-57 [in Ukrainian].

Skyba, ?. (2011). Medialiteracy of a future social pedagogues: The main features. Herald of Cherkasy Universyty. Series, Philology Sciences, 203, 109–113 [in Ukrainian].

Tsymbalenko, Y., & Horodenko, L. (2016). The structural and specific gaps emerging under the information divides impact. Science and Education a New Dimension, 16(95), 84-87 [in Ukrainian].

UNESCO. (2019). Information for All Programme (IFAP).

Zhylavskaia, I. (2009). Medialiteracy of youth. Tomsk: TIIT [in Russian].

Zrazhevska, N. (2012). Understanding of Mediaculture: Communication, Postmodern. Cherkasy: Chabanenko [in Ukrainian].

Zrazhevska, N. (2014). Mediaculture as the object of sociocimmunication researches. TV and Radio Journalism, 13, 69-77 [in Ukrainian].

Received: 28-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-10397; Editor assigned: 31-Jan-2022, PreQC No. JLERI-21-10397 (PQ); Reviewed: 14- Feb-2022, QC No. JLERI-21-10397; Revised: 28-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-10397 (R); Published: 08-Mar-2022.