Research Article: 2020 Vol: 19 Issue: 4

Paternalism in Family Firms Successor Selection

Shital Jayantilal, University Portucalense

Sílvia Ferreira Jorge, University of Aveiro

Tomás M. Bañegil Palacios, Universidad de Extremadura

Abstract

The objective of this paper is to provide insight on the impact that emotional factors have on successor selection in family firms highlighting the role played by the founder’s paternalistic leadership style on family firm successor selection. In order to do so, we model games for different paternalistic leadership styles of the founder towards successor selection and then analytically compare the results. Our paper contributes to the analysis of the impact of the type of paternalistic leadership type has, including the role emotional factors play on the challenging moment of family firm succession. The Nash equilibrium results show that the founder’s paternalistic leadership style plays a key role to ensure firm continuity as well as secure that the founder’s preferred successor is indeed appointed successor. Additionally, our findings emphasize that the emotional factors are crucial in determining the successor outcome.

Keywords

Emotions; Conflict, Emotional Value, Family Business, Succession, Paternalistic Leadership Style, Governance, Game Theory.

Introduction and Literature Review

Recently, with the Nobel prize, in 2017, awarded to Richard Thaler there has been a growing understanding that decision making is influenced by a combination of economic and also emotional factors. This has driven researchers to include these factors in the various areas of management and economics. This paper aims to study how these emotional factors affect the way family firms faces the test posed by executive leadership succession. We analyze the role that the key emotional factors (firm intergenerational continuity and family conflict) play in terms of family firm (FF) successor selection.

The family is the underlining denominator of the FF. The family firm’s singularity results from the interaction and overlap of the family and the business. This intertwining means that the firm is permeable to the family and its needs and, simultaneously, exposes the family to the challenges of the firm and its impacts. The ultimate challenge of the governance of family firms is the passing of control from one generation to the next.

The founder, being the vortex of both the business and the family, wants to ensure firm continuity without staking family harmony. His/her decision making in the FF is affected by emotional factors related to the family (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2001 & 2007; Basco & Rodríguez, 2009; Klein & Kellermanns, 2008).

In the field of family firms, given the influence that the family tends to have on the business, many scholars have shown that emotional factors play a role in decision making in the FF. Nonetheless, the impact these emotional factors have on the governance of family firms and on the FF succession process is still an open question and is essential for a better understanding of the succession process. We analyze the role that the key emotional factors (firm intergenerational continuity and family conflict) play in terms of successor selection in the FF. In order to study the strategic decision making process involved in the successor selection we resort to game theory. The use of this methodology is still quite recent to analyze successor selection as traditionally, researchers have employed both quantitative (Neubauer, 2003) and qualitative approaches (Bizri, 2016) and systematic literature review (Sharma, 2004).

Game theory is a methodology used to study strategic decision making and therefore is appropriate for our analysis. We model two family firm successor selection models that differ in the founder’s type of paternalistic leadership which include emotional factors as variables in the analysis, following a similar setup as proposed by Jayantilal et al. (2016a). The findings illustrate that the emotional factors play a key role in the successor choice in both founder’s types of paternalistic leadership. Additionally, this paper studies the impact that the founder’s type of paternalistic leadership has in terms of FF successor selection (we explore a more complete setup and thus deepen the analysis presented in Jayantilal et al. (2016b). This is an important analysis, in the context of family firms, as paternalistic leadership styles seem to be a characteristic of such firms. Indeed, the concern demonstrated by such leaders tends to be father like, where they tend to intervene and impact the decisions made by others, specially their potential successors. Some authors Lubatkin et al. (2007 & Eddleston & Kidwell (2012) highlight the negative impact that this type of leadership has yet others defend that it can also be beneficial (Mussolino & Calabrò, 2014) depending on the type of paternal leadership. To better understand this impact on FF successor selection of this type of leadership style, this paper resorts to the solid foundations of game theory to shed a light on this critical issue.

For the purpose of our analysis, we adopt the paternalistic leadership styles proposed by Aycan (2006) (and further developed by Pellegrini & Scandura, 2008). These authors denote an authoritarian paternalistic style to a founder who asserts authority and control over his subordinates, expecting their loyalty and obedience (what Michael-Tsabari & Weiss (2015) defined as an activist approach), versus the benevolent paternalistic type who wants his subordinates to thrive and achieve their individual aims, under his/her wing (Blumentritt et al., 2013). The results provide analytical evidence that founders who display authoritarian paternalistic style tend to increase the propensity of ensuring FF continuity, even in the presence of conflicts. Furthermore, this type of leadership increases the propensity of the founder’s preferred successor being appointed. For FF leaders these results are important and we hope that will compel them to be more proactive in their succession planning.

The originality of the paper lays on how it places the founder’s leadership style on centre stage, coupled with the way it includes and explores emotional factors to better understand the challenging moment of FF transition. Additionally, using game theory, the model highlights that decisions in family firms are, also, emotionally driven but should not be seen as irrational (Gómez-Mejia et al., 2001).

The paper begins with a review of the relevant literature in Game Theory and successor selection then follows the model and discussion of the results. We finalize by reflecting on the impact and limitations of our findings, and suggest future avenues of research.

Game Theory and Successor Selection

The strategic interdependence between the founder and the potential successors’ actions is part of the successor selection is a process. Depending on the founder’s paternalistic style, the family members face different decisions in the succession process. Game theory focus on strategic decision making analysis, where the outcome of a player depends on the actions of the other players. Thus, the use of game theory is completely appropriate to study the FF succession process, one of the most demanding challenges of the FF.

The application of game theory to research FF succession is still embryonic. Bjuggren & Sund (2001) considered a game that analyses the impact of legal and transactional costs on alternative ownership succession options. Burkat et al. (2003) model focused also on how the legal setting affects the decision of leaving the firm to a family member or to a professional manager. Lee et al. (2003) showed that families tend to choose a successor from inside the family in high idiosyncratic businesses. Their payoff function included the successor’s ability and remuneration. Michael-Tsabari & Weiss (2015) study succession in family firms using the Battle of the Sexes game. They showed that deficient communication leads to disagreements between father and son. Blumentritt et al. (2013) discussed a game where the children simultaneously decide to run for the CEO position, and then the father chooses his/her successor. In their paper they considered the situation when both children compete for the top position in the FF, and this can lead to conflict but not considering emotional cost as a variable. In their game, the founder reacts to his/her children’s strategic option to pursue, the successor position, and chooses his/her successor in accordance to the relative importance the founder gives his/her children’s desire and ability.

In Mathews & Blumentritt (2015) sequential game, the children chose the level of effort to employ to pursue the FF CEO position, given the father’s preference and thus discussed first-mover advantage and acknowledged situations where discord among siblings could occur, but not considering explicitly the cost of sibling rivalry in their payoff functions. Jayantilal et al. (2015) study the impact of culture on successor selection. Their results highlighted the importance of cultural congruence between generations to ensure family harmony and firm longevity. More recently Jayantilal et al. (2016b), showed the impact on successor selection of the emotional cost of conflict resulting from sibling competition where the collaborative family outcome, which resulted from family members cooperating and acting as a unit, is better in promoting firm intergenerational succession and ensuring that the founder’s preferred child is appointed successor. Our paper advances the use of game theory to study successor selection, emphasizing the impact of the founder’s leadership style and the role of the emotional factors will have on the approach he adopts towards the succession process.

The Model

Describing family decision making

We consider two sequential games of complete and perfect information this setup formally integrates, in the payoff functions of all players, the emotional factors. Continuity and conflict are ley emotional factors which are contemplated in the setup. The emotional benefit is related to intergenerational succession. The emotional cost relates to conflict, which can arise from founder/child tensions regarding the succession and/or from siblings competing for the position. The founder/parent (F) takes into account each child’s Leadership Skills (Li where i=E, Y) and level of Family Orientation (Oi). Li can be seen as an umbrella concept encompassing all the child’s managerial skills, and measures his/her ability of realizing the firm’s performance (Lee at al., 2003; Blumentritt et al., 2013). Li refers to the business dimension, whereas Oi relates to the family dimension (Lumpkin et al., 2008). The degree the founder values the business dimension (Li) is given by α (α >0). β denotes the significance that the founder attributes to the successor bringing a greater sense of family to the FF (β >0). It is the weighed sum of the successor’s ability to maximise the firm’s potential (business dimension) and the successor’s valuation of family involvement in the firm (family dimension), which reflects the founder’s utility. The variable I denotes the boost in the founder’s payoff resulting from his/her chosen successor accepting the invitation (I>0). This is seen as an emotional benefit, of being respected, from the founder’s perspective. When both siblings compete for the top position in the FF, this can give rise to sibling conflict, which has a negative effect on family harmony. This is an emotional cost - the cost of conflict - and represented by cj (where j=F, E, Y) and is incurred by all the players (cj≥0). Founders with higher values of cj are those who value family harmony. N (N>0) reflects the negative payoff that the founder registers, when his/her chosen successor declines the invite to succeed him/her, and his/her other child decides not to run for the position. When neither child is interested in succeeding, this will reflect negatively (i.e. an emotional cost) on the founder’s utility, given that continuity is a key aspect of socioemotional value of the FF (Zellweger et al., 2008 & 2012). Founders exhibiting higher values of N are those who significantly value the firm staying in the family.

Now we take a closer look at the variables, which impact the children’s payoffs: Hi indicated the value each child places in becoming the successor and heading the FF (Hi >0). This should be seen as the total of the financial and the emotional benefits that he/she earns from taking that position. The emotional benefits include the value that the child attributes to the firm’s executive power staying in the family, as well as other non-economic benefits he reaps such as such as social status and power. The cost of running given by r (r ≥ 0) shows the effort the child needs to make if he/she wants to compete to becoming the FF next CEO. The underlining assumption is that this cost is the same for both children and is suppressed by the value given to head of the FF (Hi>r). [1] When the founder invites a child then he/she doesn’t sustain any cost of running (r=0) but if he/she opts for a career outside the FF this can may lead to conflict with the founder. Going against (ai>0) the founder’s expressed wishes is a relevant emotional cost for all involved. The scope of this cost is directly influenced by the founder/child relationship. A child who puts the founder on a pedestal, and is submissive towards him/her, will have a propensity for higher levels of ai (a conservative succession pattern as defined by Miller et al., 2003). In such cases the child will find it more difficult to decline the founder’s invitation and chose a career away from the FF. Finally, Bi (Bi>0) is the payoff the child obtains from his/her best career option outside the FF, net of all costs sustained in attaining it. Notice that this is the value the child places on that outside option. [2]

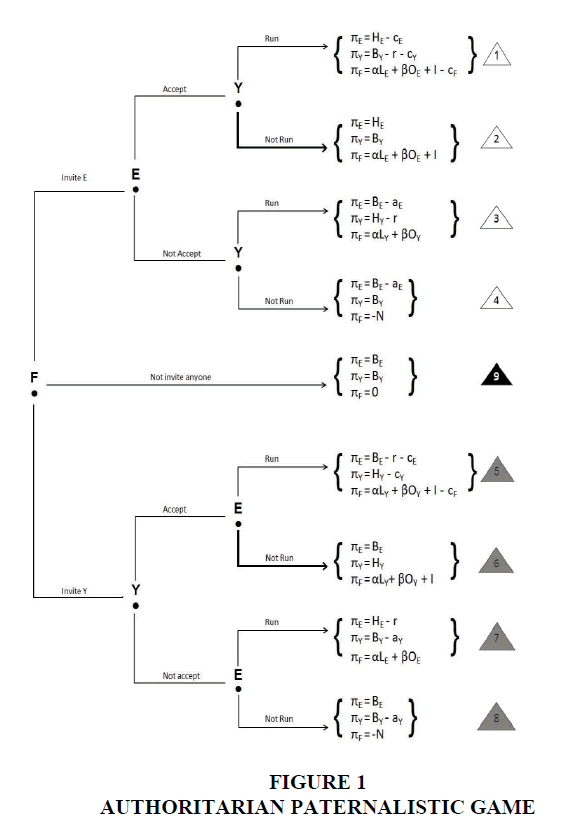

Authoritarian Paternalistic Style

In this first game, F, with an authoritarian paternalistic style, kicks off the succession process by addressing an invitation to one of his children to head the FF. [3] that child can accept or decline the invite. Subsequently his/her sibling will decide to run or not for the head position in the FF. Figure 1 illustrates this game tree.

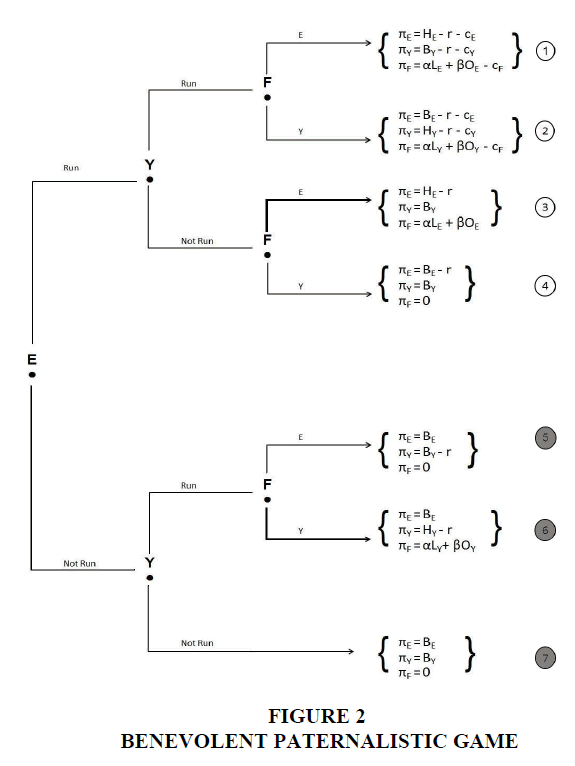

Benevolent Paternalistic Style

As opposed to an authoritarian paternalistic founder, in this approach, the founder adopts a more reactive role and doesn’t invite any of his children but responds when they run for the position. Following Jayantilal et al. (2016a), the game modelled for this selection is of perfect and complete information. In this game the elder child (E) moves first by opting to run (or not run) for the top position in the FF. Next, the younger child chooses to run (or not) and finally the founder makes his/her choice and appoints his successor. This game is presented in Figure 2.

Results

Nash Equilibria Analysis

To find the equilibrium solution for sequential games with perfect information, backward induction is used. We start at the last node, and choose the best option. Then, proceed to the next-to-last, identifying the optimal action for the player, and continue this procedure, until arriving at the root. The underlying logic is that the player anticipates what the other players after him/her are going to play and factors this in when making his/her decision. This reasoning comes to a conclusion in what is defined as the Perfect Nash equilibrium (Kreps, 1990).

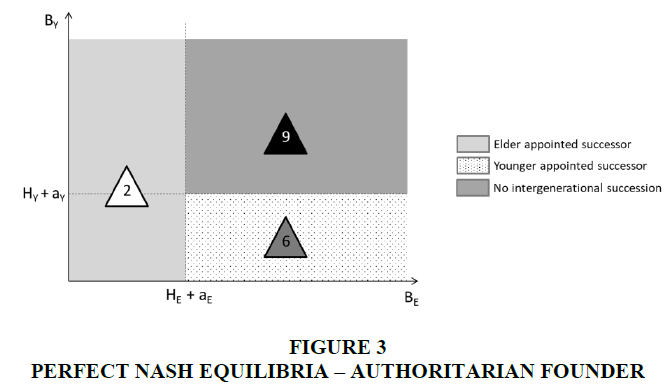

Applying this technique to the game illustrated in Figure 1, we achieve three possible Nash equilibrium solutions. Figure 3 summaries the equilibrium paths and successor outcomes.

Considering a F who prefers the business dimension, i.e. α > kβ; k = (OY - OE)/ (LE - LY), the results indicate that in the situation when the value that both children place in pursing their career options outside the FF is such that they prefer to do so, even at the cost of going against the founder’s wishes (B>H+a) then FF executive control will not be secured in the family. The risk of intergenerational management succession not being secured will be diminished when children are more submissive to the founder and so do not want to go against the founder’s wishes (higher levels of ai). In case only one child is available to succeed (i.e. BE>HE+aE and BY<HY+aY or BE<HE+aE and BY>HY+aY) then he/she will be appointed. This is the case because, for the founder, intergenerational continuity is an emotional benefit that overrides all other options (i.e. appointing an outsider or closing or selling the firm). When both children are interested in being named successor, then the founder will need to choose.

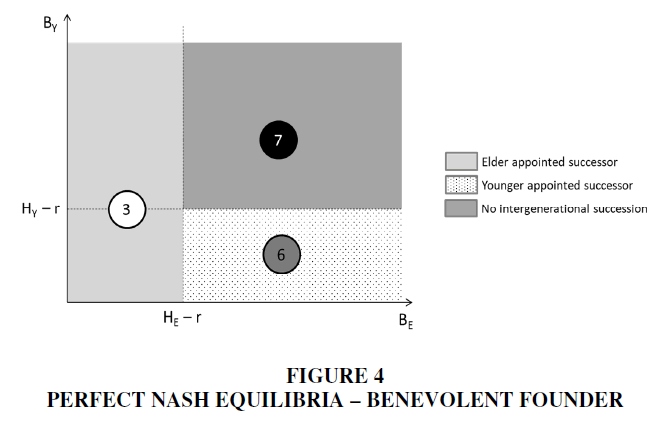

Applying the backward induction technique to the game tree of Figure 2, we attain three Perfect Nash equilibria. The successor outcomes and equilibrium paths are shown in Figure 4.

The firm’s executive control does not stay in the family, if both children prefer to pursue their careers elsewhere (i.e. when Bi> Hi-r) then. In the situations when only one of the siblings wants to head the FF, then he/she child will end up being appointed.

Therefore, only in the case when both siblings compete is the successor outcome influenced by the founder’s preferences. In that particular case, it is the founder’s tendency regarding the family or the business dimension which settles the selection. E will be chosen if F is more inclined to the business dimension, i.e. α > kβ; k = (OY - OE)/ (LE - LY), or else he will prefer Y. It is important to note that even in the situation where the founder more predisposed to choose Y, Y faces an additional challenge for becoming the successor due to the emotional cost he suffers because of running against his/her sibling (cY). The more averse Y is to facing sibling conflict, the higher the tendency that will name successor.

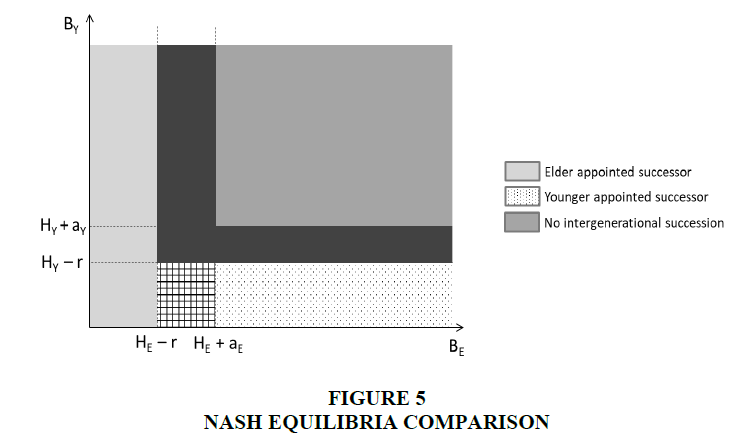

Discussion

The founder's paternalistic leadership type has impact on the successor selection since the perfect Nash equilibrium outcomes are different. Additionally, the key emotional factors, relating to FF continuity and family harmony, are also important in defining the successor selection. To study the impact, in terms of succession outcomes, of a founder who denotes an authoritarian paternalistic leadership and initiates the succession process by inviting one of his/her children to succeed him/her, in comparison to one who responds after his/her children take the initiative, we overlapped the succession outcomes for both approaches as shown in Figure 5.

When both the children value their career options outside the FF such that they are unavailable to succeed the founder, it increases the propensity of the firm executive control not remaining in the family. This shows that even when the founder is an authoritarian paternalistic leadership type he still faces the possibility of not being able to ensure intergenerational succession. However, if he doesn’t actively initiate the process then there´s a higher risk that the firm’s executive control will not stay in the family. In other words, a founder who values intergeneration succession will be more successful ensuring the firm’s continuity if he takes a proactive stance, although there is the possibility that both children might prefer to pursue other career options besides heading the FF. The authoritarian paternalistic style type founder places the onus on the child, making it more difficult for him/her to consider other career options, due to the emotional cost the children incur when they opt to go against the founder’s wishes (ai). As illustrated by the L shaped shaded area in Figure 5, the more averse the children are to conflicting with the founder (higher ai) then the greater the propensity of the firm’s continuity being assured. The emotional cost is important in determining that increase but also the effort they are required to expend to be considered as potential successors (given by r). In some firms the requirements to be considered as a potential candidate are very demanding, whilst in others these can be as low as showing interest.

The founder’s paternalistic style and approach towards the succession process directly influences whether the family firms’ executive control remains in the family. Comparing both games, it is evident that the propensity of the founder’s preferred successor taking over the executive control of the firm is increased by the founder taking an authoritarian paternalistic style. To help illustrate the point, let’s consider that E would rather pursue his/her career outside the firm but is unwilling to go against the founder’s expressed wishes and also assume the founder values the business dimension more than the family dimension (i.e. HE-r < BE <HE+ aE). In this particular case, E will only be appointed successor if F assumes an authoritarian paternalistic style, else E will opt out of the FF, in which case intergenerational succession might be jeopardized. The rectangular chequered area in Figure 5 shows the increase in the propensity of E being appointed successor (in detriment of Y) simply due to F assuming an authoritarian paternalistic style.

If, on the contrary, the founder values the family dimension more than the business dimension, then he will prefer Y. Figure 5, shows that Y becoming successor is less prone to occur if F doesn’t invite him/her. To illustrate this, consider the case that Y wants to head the FF but is unwilling to risk family harmony by running against E (extreme high values of cY). In this case, he will only become successor if E is not interested. If, on the other hand, Y is a child who really does not care about the conflict, which might result from sibling competition (very low values of cY), then he will be appointed successor so long as he is available (HY-r > BY). However, even in this particular situation, and assuming that Y is the founder’s preferred successor, still it is more likely that Y is appointed successor if F adopts an authoritarian paternalistic style (and not a benevolent paternalistic style) and invites him/her (as illustrated in Figure 5 by the chequered rectangle).

The successor outcomes highlight that the emotional costs are important in defining the results. The more reluctant the children are of going against the founder’s wishes (high levels of ai) the higher the impact the founder adopting an authoritarian paternalistic style has in assuring FF intergenerational continuity. Additionally, the founder’s preferred successor is more likely to be appointed successor (illustrated by the checked areas) if the founder invites him/her, rather than if F waits for him/her to show interest and run for the position.

In terms of the emotional factors, this paper also shows their impact in the equilibrium outcomes. A child who is affectively committed to the family and the firm will derive more emotional benefits from becoming CEO of the family firm and thus this will lead to high levels of Hi, resulting in a lower propensity of intergenerational succession not being secured.

The perfect Nash equilibrium results show that the emotional cost included in our analysis resulting from the conflict between competing siblings and the founder/child conflict (captured by ai in our model) is important in determining the successor outcome. The higher the importance that children attribute to respecting and fulfilling the founder’s expressed wishes, the greater the propensity of intergenerational succession being assured.

The emotional cost when the child decides to run against his/her sibling (captured by cj) is also an important factor in determining the equilibrium paths and subsequently the successor outcomes in the case of the authoritarian paternalistic style (section 3.2). Whereas cF and cE are important in terms of determining the equilibrium path of the games they do not directly influence the successor outcomes. While cY, in the case of a benevolent paternalistic founder, has a direct influence on who is appointed successor. Consider the situation when E informs of his/her interest to succeed the founder. Y must then decide whether to race against his/her sibling or not. If we consider that Y is extremely conflict averse (high values of cY), for instance, the propensity of E being appointed successor is increased. [4,5]

Conclusion

Intergenerational management succession is a hallmark in FF continuation. This paper uses game theory methodology to give a better understanding of the effect of that the founder’s paternalistic style can have on successor selection, highlighting the part played by the emotional factors. The results indicate that in the choice of successor, the emotional factors play a key role. The emotional costs resulting from sibling as well as those from founder/child conflict or sibling conflict are very important in that selection. Furthermore, and in light of the recent Nobel laureates’ works, we call for research in family firms aiming to better comprehend the role that emotional factors have in the decision making process by extending beyond the ones presented.

The originality of this paper is that in addition to including the emotional factors, it brings the effect of the founder’s leadership style on successor selection to centre stage. The findings undeniably show that for FF founders who are of a more benevolent type, there is a higher propensity that, on the one hand, the founder’s preferred successor will not be appointed, and on the other, and more disturbing, that the FF intergenerational continuity is not secured.

Our results extend FF literature on factors contributing to firm longevity but also, for practioners, draw attention to some critical aspects which they should be taken into account tackling the challenges related to successor selection in FF. These results highlight that paternalism is not detrimental, and in fact, even authoritarian paternalism helps attain FF continuity. This should not be understood as the need for more authoritarian founders, but rather for practitioners and consultants working with FF, to motivate the founders to be less hesitant to trigger the succession process.

In order to contribute to the longevity of these firms, which are significant in terms of number and their contribution to the growth and employment in the global business arena, this paper provides analytical evidence of how the founder can condemn his/her firm’s continuity if he adopts a benevolent paternalistic style. Providing an analytical demonstration of the role that the type of paternalistic leadership style can have on FF longevity is another important contribution that this paper makes.

Lastly, from a methodology perspective, this paper provides an extension of the use of game theory in the study of executive successor selection in FF, which is still in its early stages but has been gaining impetus. We call for future research to broaden its use by including other scenarios, such as: other types of succession processes (i.e. 2nd and/or 3rd generation), allowing for more/different stakeholders (i.e. nonfamily members) and, finally, analysing FF governance mechanisms (i.e. protocol design). In, inevitable, next steps will be, in terms of methodology, to resort to behavioural and experimental techniques in the field of FF research.

End Notes

[1]This cost of running is similar to the cost of choosing to “pursue” as presented by Blumentritt et al. (2013) and by adopting this assumption we eliminate the case where a child runs only because he has nothing better to do. The analysis with different costs for each child adds to the complexity but produces no significant differences on the conclusions obtained.

[2] Consider the following case of Y which, after F invites E and E accepts then Y doesn’t put up a fight to avoid conflict even though he/she would have preferred to become the successor. In this case, Y will have values of BY lower than one who prefers to follow his career outside the FF.

[3] There is no need to limit technically the choice to family members but given that the aim is to understand intergenerational succession, all other options have been excluded, i.e., selling the firm and/or hiring professional management.

[4] If Hi-r = Bi and/or Hi +ai = Bi, we assume the child prefers pursuing the top position in the FF.

[5] The founder’s choice depends on the children’s relative attributes and his/her valuation of those attributes. If α(LE – LY)- cF > β(OY – OE)- cF, the founder will opt for path 2, and invite E. Whereas for a founder with the opposite preference, the equilibrium path will be path 6 and Y will be his/her selected successor. It’s assumed F chooses the elder child when F is indifferent between choosing his/her elder or younger child.

Acknowledgements

This article was financed by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., in the scope of project UIDB/05105/2020.

References

- Aycan, Z. (2006). Paternalism: Towards conceptual re?nement and operationalization. Scientific Advances an Indigenous Psychologies: Empirical, Philosophical, and Cultural Contributions (London: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 4-45.

- Basco, R., & Pérez Rodríguez, M.J. (2009). Studying the family enterprise holistically: Evidence for integrated family and business systems. Family Business Review, 22(1), 82-95.

- Bizri, R. (2016). Succession in the family business: drivers and pathways. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research.

- Bjuggren, P.O., & Sund, L.G. (2001). Strategic decision making in intergenerational successions of small-and medium-size family-owned businesses. Family Business Review, 14(1), 11-23.

- Blumentritt, T., Mathews, T., & Marchisio, G. (2013). Game theory and family business succession: An introduction. Family Business Review, 26(1), 51-67.

- Eddleston, K.A., & Kidwell, R.E. (2012). Parent–child relationships: Planting the seeds of deviant behavior in the family firm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 369-386.

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R., Haynes, K.T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K.J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106-137.

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R., Nunez-Nickel, M., & Gutierrez, I. (2001). The role of family ties in agency contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 81-95.

- Jayantilal, S., Bañegil Palacios, T.M., & Jorge, S.F. (2015). Cultural dimension of Indian family firms: Impact on successor selection.

- Jayantilal, S., Jorge, S.F., & Bañegil Palacios, T.M. (2016a). Founders’ approach on successor selection: Game theory analysis.

- Jayantilal, S., Jorge, S.F., & Palacios, T.M.B. (2016b). Effects of sibling competition on family firm succession: A game theory approach. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(4), 260-268.

- Klein, S.B., & Kellermanns, F.W. (2008). Editors' notes. Family Business Review, 21(2), 121-125.

- Kreps, D.M. (1990). Game theory and economic modelling. Oxford University Press.

- Lee, K.S., Lim, G.H., & Lim, W.S. (2003). Family business succession: Appropriation risk and choice of successor. Academy of Management Review, 28(4), 657-666.

- Lubatkin, M.H., Durand, R., & Ling, Y. (2007). The missing lens in family firm governance theory: A self-other typology of parental altruism. Journal of Business Research, 60(10), 1022-1029.

- Lumpkin, G.T., Martin, W., & Vaughn, M. (2008). Family orientation: Individual-level influences on family firm outcomes. Family Business Review, 21(2), 127-138.

- Mathews, T., & Blumentritt, T. (2015). A sequential choice model of family business succession. Small Business Economics, 45(1), 15-37.

- Michael-Tsabari, N., & Weiss, D. (2015). Communication traps: Applying game theory to succession in family firms. Family Business Review, 28(1), 26-40.

- Miller, D., Steier, L., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2003). Lost in time: Intergenerational succession, change, and failure in family business. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(4), 513-531.

- Mussolino, D., & Calabrò, A. (2014). Paternalistic leadership in family firms: Types and implications for intergenerational succession. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(2), 197-210.

- Neubauer, H. (2003). The dynamics of succession in family businesses in western European countries. Family Business Review, 16(4), 269-281.

- Pellegrini, E.K., & Scandura, T.A. (2008). Paternalistic leadership: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 34(3), 566-593.

- Sharma, P. (2004). An overview of the field of family business studies: Current status and directions for the future. Family Business Review, 17(1), 1-36.

- Zellweger, T.M., & Astrachan, J.H. (2008). On the emotional value of owning a firm. Family Business Review, 21(4), 347-363.

- Zellweger, T.M., Kellermanns, F.W., Chrisman, J.J., & Chua, J.H. (2012). Family control and family firm valuation by family CEOs: The importance of intentions for transgenerational control. Organization Science, 23(3), 851-868.