Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Pathways towards Sustainable Business Model for Malaysian Microenterprises

Noor Azam Samsudin, Universiti Selangor (UNISEL) Malaysia

Zuraini Alias, Universiti Selangor (UNISEL) Malaysia

Noor Ullah Khan, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan (UMK) Malaysia

Hanieh Alipour Bazkiaei, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan (UMK) Malaysia

Abstract

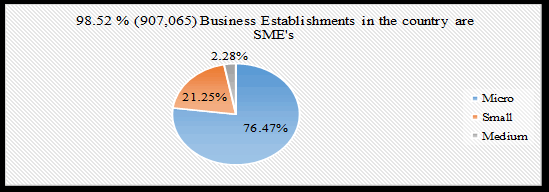

Microenterprises (MEs) play an integral role in both developed and developing economies. In Malaysia, these enterprises make up around 76.47% of total SME establishments (Department of Statistics, 2019). This research paper provides an overview of microenterprises based on secondary data and supportive literature. In addition, it provides critical insights into the problems related to microenterprise and business model practices significance how it essential for improving ME performance and productivity. Finally, it offers vital discussion and concludes the overall research.

Keywords

Microenterprises, Business Model Practices, Performance, and Productivity

Introduction

Microenterprises (MEs) are considered the backbone of every economy in most countries worldwide (Akbar, Omar, Wadood & Al-Subari, 2017; Thaker, 2018) and an important area for research. Similarly, in Malaysia (Jamak et al., 2014; Chin & Lim, 2018). Microenterprise is a promising approach to poverty alleviation through business development, used as an effective remedy for regional and global economic recession (Geremewe, 2018). Microenterprise (ME) is an integral element of contributing to the global economy. Large economies like the USA and UK have been boosted by the presence of Micro Enterprises and Entrepreneurship (Doran, McCarthy & O’Connor, 2018). In both developing economies such as African nations (Omoruyi, Olamide, Gomolemo & Donath, 2017) and emerging economies like China (He & Qian, 2019), micro enterprises contribute to the economy in terms of employment and GDP more than other larger medium and large size organizations. Similarly, there is a growing tendency of microenterprises in different regions worldwide, such as ASEAN (e.g., Malaysia, Indonesia) (Muradin & Ibrahim, 2018) and other regions like Mexico and Latin America (Muñoz & Mayor, 2015; García, 2018). Previous studies have reported about various benefits of microenterprises such as job creation (Amoah & Amoah, 2018), poverty alleviation (Geremewe, 2018), economic improvements (Tahir, Razak & Rentah, 2018), community development (Purusottama, Trilaksono & Soehadi, 2018), socio-political betterment (Maksum, Rahayu & Kusumawardhani, 2020). All these benefits contribute to economic growth in transforming societies and creating jobs and revenue creation (Jamak et al., 2014).

Review of Literature

Previous literature on characteristics confirms that Microenterprise (MEs) is owned mainly by a single owner or manager and has few employees and limited capital capacity (Al Mamun & Ibrahim, 2018). These enterprises have diverse nature and operate in different sectors, including service, manufacturing, and sales-related activities (Razak, Abdullah & Ersoy, 2018). Such enterprises' organizational structure and management are mainly simple such as sole proprietorship, family enterprise, limited by employees (Rahman, 2017). These enterprises make seasonal and situational adjustments to survive while adopting flexible strategies to meet market demands due to their small size and capital constraints (Shafi, Yang, Khan & Yu, 2019). The business start-up of microenterprises is easy, but it is pretty challenging to stay competitive in the market to absorb economic shocks and need capital support for survival (Rahman, 2017; Rahmawati, 2018).

Microenterprise is mainly categorized as under small-scale business. These enterprises possess different features from other companies. There are various definitions available in the literature about microenterprise. Such as a microenterprise in China is defined as “a business with annual gross receipts of up to one million US dollars.” Both in the US and Europe and region, about one-third of enterprises are micro in nature. See Table 1

| Table 1 Microenterprise Definitions |

|

|---|---|

| Definitions | Authors |

| “Microenterprises are generally defined as commercial enterprises that have ten or fewer employees.” | Ajibefun & Daramola (2003) |

| “Microenterprise can be defined as “An enterprise which employs fewer than ten persons and whose annual turnover and annual balance sheet total do not exceed EUR 2 million”. | ‘Commission of the European |

| Communities’ (2003) | |

| “According to World Bank, a microenterprise consists of approximately ten employees and a total worth of $10,000 with a $100,000 annual sale”. | Ayyagari, Beck & Demirguc-Kunt. (2007) |

| “A sole proprietorship, partnership, limited liability corporation or corporation that has fewer than five employees, including the owner, and generally lacks access to conventional loans, equity, or other banking services.” | U.S. ‘Small Business Administration’ (2010) |

| “In Malaysia, a micro-enterprise is defined as “a business establishment with a sales turnover of less than RM300, 000 or less than five full-time employees”. | ‘SME Corp. Malaysia’ (2019) |

Microenterprise performance is vital for the economic growth and development of the country (Tahir, Razak & Rentah, 2018). Likewise, Malaysian SMEs have created greater performances by contributing around 35% to (GDP) still need improvement, as compared to developed countries to share of enterprises, are above 50%, e.g., Italy with 70% in terms of contribution to GDP (Chin & Lim, 2018). Previous studies have mainly focused on SME’s performance, while the main contribution to GDP comes from microenterprises in Malaysia. Table 2 has revealed that among SME’s the maximum number of establishments comes under microenterprises, i.e., 693,670.

| Table 2 Total Number of Smes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | Micro | Small | Medium | Total SME’s | Total SME’s |

| Number of Establishments | % Share | ||||

| Service | 649,186 | 148,078 | 11,862 | 809,126 | 89.2 |

| Manufacturing | 22,083 | 23,096 | 2,519 | 47,698 | 5.3 |

| Construction | 17,321 | 17,008 | 4,829 | 39,158 | 4.3 |

| Agriculture | 4,863 | 4,143 | 1,212 | 10,218 | 1,1 |

| Mining& Quarrying | 217 | 458 | 190 | 865 | 0.1 |

| Total SME’s | 693,670 | 192,783 | 20,612 | 907,065 | 100.0 |

This study focuses on service sector microenterprises which consist of around 649,186 enterprises, which contribute nearly 71.56% to SME’s. The service sector is the main contributor to GDP, which provides about 23.9 % in 2018 (SME Corp. Malaysia 2019). The previous research work has focused chiefly on SME’s and ignored this part which mainly contributes to GDP and the overall economy. Research revealed that the development of microenterprises through integrated approaches and programs could improve productivity and accelerate economic growth.

A microenterprise is defined as “a business establishment with a sales turnover of less than RM 300,000 or less than five full-time employees”. Table 2 statistics show that SMEs are almost 98.52 % across all sectors of the economy, including 89.2 % service sector, 5.3% manufacturing, 4.3% construction, 1.1% agriculture, and 0.1% mining. In Malaysia, microenterprise establishments make up around 76.47% of the total SME establishments, followed by small 21.25% and medium only 2.28%. Figure 1 shows the bar chart of data presented in the SME annual report 2018-2019 (Department of Statistics, 2019).

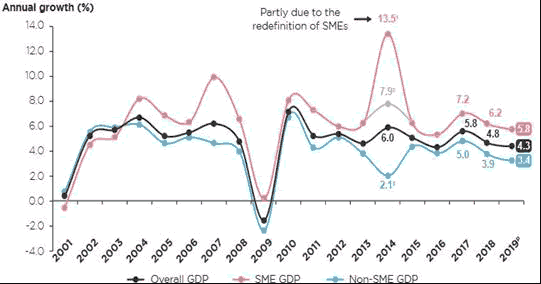

SME GDP growth expanded at a moderate pace of 5.8% in 2019 compared to 6.2% in the preceding year, in line with Malaysia’s economic slowdown in 2019 due to the challenging global economic environment and domestic supply disruptions. Nevertheless, the growth performance of SMEs remained higher than the overall GDP and Non-SME GDP, which registered a growth of 4.3% and 3.4%, respectively, as reflected in Figure 2. A comparison of the GDP growth of SMEs and Non-SMEs suggests that SMEs are more agile and quick to change because of their small size, privately owned, and relatively simpler corporate structures, all of which can be beneficial during a crisis. (Figure 3)

Figure 2: SME GDP, NON-SME GDP, and Overall GDP Growth (%)

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia and SME Corp. Malaysia (2020/2021)

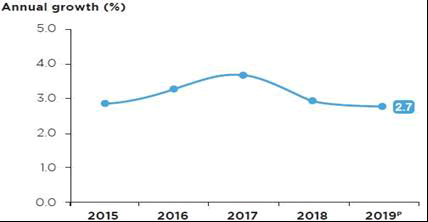

Figure 3: SME Productivity Growth (%)

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia and SME Corp. Malaysia (2020/2021)

Labor productivity per employee refers to the efficiency and effectiveness of each employee to generate value-added or overall output. It is calculated by using the ratio of value-added of SMEs at constant prices to the SME employment by the economic sector in Malaysia. The labor productivity of SMEs in Malaysia has maintained steady growth over recent years, although the pace of growth has moderated slightly. In 2019, SME labor productivity grew by 2.7% (2018: 2.9%) to RM75, 457 per employee compared to RM73, 449 per employee in 2018.

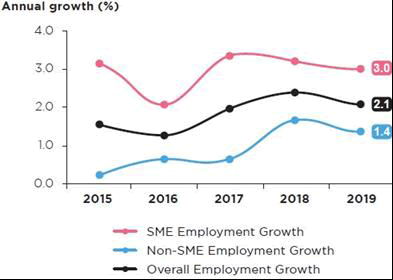

In 2019, SMEs in Malaysia employed 7.3 million people compared to 7.1 million people recorded in 2018, denoting an increase of 3.0%. SME employment growth was supported by all sectors except the construction sector, which registered negative growth during the year (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: SME Employment, Non-Sme Employment, and Overall Employment Growth (%)

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia, and SME Corp. Malaysia (2020/2021)

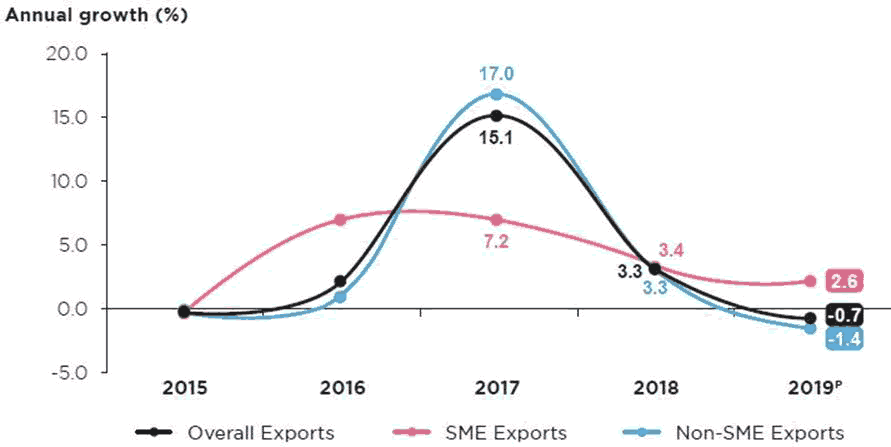

In 2019, SMEs continued to record a positive export growth of 2.6% (2018: 3.4%), despite weaker external demand, ongoing trade tensions between United States (US) and China, and lower commodity production during the year (refer to Figure 5). The Non-SMEs, on the other hand, was far more affected as it contracted by 1.4%, the first decline since 2013.

Figure 5: SME Exports, Non-Sme Exports and Overall Exports Growth (%)

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia, and SME Corp. Malaysia (2020/2021)

Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on SMEs Enterprises

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) represent more than 90% of global businesses, contribute significantly to job creation and inclusive economic development. The World Bank estimates about 600 million jobs will be needed by 2030 to absorb the growing global workforce, making SME development a great priority for many governments worldwide. The development of micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) has always been a high priority for the Government. They make up to 98.5% of business establishments and contribute 38.9% to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2019. In 2019, SMEs employed about 7.3 million people, thus contributing 48.4% to the country’s employment. The very essence of survival of this significant employer to the country is hanging in the balance due to the unparalleled impact of COVID-19. This years’ Report is aptly themed ‘SMEs in the New Normal: Rebuilding the Economy.’ A worthy endeavor indeed, given the significance of accurate and deep understanding of SME issues, challenges, catalysts, and performance that are timely to guide our progressive actions in the SME development space and framing our response to the COVID-19 crisis (SME Corp. Malaysia, 2021).

The Government takes cognizance that the SME sector is one the most vulnerable groups affected by the pandemic, with 89.9% experiencing a sudden drop in sales during the initial containment period. The economic initiatives introduced under these stimulus packages have been instrumental in addressing critical pandemic-related issues faced by businesses, especially SMEs in the financing, cost of doing business, cash flow, job retention, human capital development, infrastructure development, and adoption of technology and digitalization. The crisis has sharpened the need to build resilient, sustainable, and inclusive ecosystems for SMEs, with technology and digitalization taking center stage. Anchoring these standpoints, the Government will continue the momentum of the economic recovery that has been mobilized since May 2020 to provide various assistance to SMEs. At the same time, challenges in accessing finance persist for microenterprises, start-ups, and innovative ventures with novel business models. Indeed, the rapid change in the business models and ecosystem, partly accelerated by COVID-19, is a testimony that every challenge is a disguised opportunity, a lesson to learn, and a chance to grow (SME Corp. Malaysia, 2021). Considering the revenue loss by business size, microenterprises which make up 76.5% of total business establishments in Malaysia unequivocally, will be the hardest-hit business sector. The comparison of all three stages has shown in Table 3

| Table 3 Summary of Sme Scenario in Pre-Pandemic, During Mco and Post-Mco |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Pandemic | Under MCO | Post-MCO |

| • 55.4% of SMEs anticipated an increase in sales | 78.9% of SMEs have cash that can last for less than three months. | Drop-in sales reduced from: May: 65.6% Aug: 49.6% |

| 44.3% of SMEs expected business to improve in the next six months. | • 72.4% had to temporarily close business operation | Worker’s retrenchment dropped from: May: 14.2% Aug: 12.0% |

| 34.6% of SMEs faced a cash-flow problem. | 58.6% recorded no sales. | Business ceasing operations decreased from May: 1.6% Aug: 1.4% |

| 39.4% can only be able to sustain for only a month or less | ||

| 19.2% experienced business loss of RM100,000 and above | ||

SME Corp. Malaysia (2021). SME Insights 2019/20

Key Issues and Problems

Despite their importance and contribution, a considerable number of empirical studies have investigated the problems of microenterprises. The Malaysian case is not an exception, and many empirical studies have highlighted these problems (Jamak et al., 2014; Muridan & Ibrahim, 2018; SME Annual Report, 2020/2021; SME Masterplan, 2020). It is pretty encouraging to see an increase in the number of microenterprises start-ups, but the main challenge is to sustain their performance in the long run (Mor, Madan, Archer & Ashta, 2020). The failure rate of new enterprises is almost 90% within five years of their operations, and only 10% of microenterprises could perform beyond a 10-year timeframe (Ahmad & Seet, 2009).

Similarly, the majority of Malaysian microenterprises are experiencing stagnation, which results in low performance. The Malaysian government has helped more than 2,000 microenterprises through mentoring and coaching programs to upgrade these enterprises by performance improvement and increase the capabilities of entrepreneurs. National SME Development Council of Malaysia (NSDC) was launched a special program on how to increase and improve microenterprise performance in terms of microenterprises annual sales. Out of 2,000 microenterprises, only 10% had successfully achieved yearly sales of RM250,000 and hence upgraded to SMEs (Muhammad et al., 2010).

Specifically, studies have focused on entrepreneurs’ demographic variables, motivation, entrepreneurial problems, governmental assistance programs, and the process of business initiation in Malaysia (Genty, Idris, What & Kadir, 2015; Li, Ahmed, Khan & Naz, 2020). Business model positively related to SME’s performance in the manufacturing sector in Malaysia. Hence Business Model (BM) practices can be vital for microenterprise performance (Cucculelli & Bettinelli, 2015).

Low microenterprises performance in Malaysia is due to lack of managerial capabilities (Pillai & Dam, 2017), incompatibility business model practices (Rahman, Yaacob & Radzi, 2016), lack of proper training and motivation of owners and microentrepreneurs to continue their business (Jamak, Ibrahim, Salleh & Noor, 2014). The level of literacy among microentrepreneurs is still alarming and nurturing of microentrepreneurs is essential for entrepreneurial development programs (Khan & Anuar, 2018) to improve microenterprise performance in Malaysia. Microentrepreneurs and owners engage business coaches for many reasons (Verdugo, 2018). Microentrepreneurs and business owners can benefit from business coaches who show understanding and provide feedback (Kotha, Lin, Corboz & Vissa, 2019). Furthermore, experienced business coaches equip entrepreneurs with the skills to run firms effectively. Business coaches work with entrepreneurs to upgrade entrepreneurs’ lack of experience and provide them education, training, and feedback on performance (Abdelkarim, 2018).

Based SME annual report, Microenterprise (ME) performance has decreased. However, the total business financing to ME financing has increased significantly from 2010 to 2017, indicating low ME performance (SME Annual Report, 2019). To address the problems, e.g., stagnation and low performance of Malaysian microentrepreneurs, they need to upgrade their micro-business to a higher business echelon of SMEs in Malaysia (Jamak et al., 2014). Therefore, microentrepreneurs and owners need to enhance their skills through training and awareness programs, i.e., business coaching and applying business model practices to improve microenterprise performance. Business model (BM) practices are composed of four components, i.e., product, customer interface, infrastructure management, and financial aspects (Dijkstra, van Beukering & Brouwer, 2020).

Research Discussion and Implications

In academic research, studies on microenterprises are relatively less recognized than large, medium, and small-scale enterprises. Indeed, research on ME’s is a relatively novel field of study. Previous studies on Business Model (BM) practices were largely conceptual. Such as focused explicitly on defining business models and identifying their main elements (Nielsen et al., 2018). Some researchers have studied the archetypes and taxonomies of BM (Hodapp, Remane, Hanelt & Kolbe, 2019). Subsequent research studies have emphasized BM in young entrepreneurial firms (Wang & Jiang, 2019). Specifically, few studies examined the role of the BM in value creation in the context of e-business firms and virtual markets. Another stream of researchers has focused on the link between business model innovation and the commercialization of new technologies (Flammini, Arcese, Lucchetti & Mortara, 2017). Researchers show increasing scholarly interest in studying business model concepts (Šimberová & Kita, 2020). However, these mentioned studies have several shortcomings, e.g., these studies ignored to examine the antecedents and components of the business model. Similarly, research on business models generally conceptual, and few empirical studies was founded (Bican & Brem, 2020). However, a first systematic literature review covering near to two decades of Business model research emphasizes that existing studies have largely overlooked the question of internal business model drivers (Foss & Saebi, 2017). Specifically, there is limited research on whether and how the firm’s strategic flexibility influences the adoption of business model practices (Miroshnychenko, Strobl, Matzler & De Massis, 2020) and improves enterprise performance. The literature stream provides limited empirical insights on the internal drivers of the business model such as strategic flexibility (Clauss et al., 2019) business model practices that remain uninvestigated. The key antecedent, i.e., strategic flexibility, is integral for business model practices and improving performance. This study's theoretical contribution is to the strategic flexibility literature (Miroshnychenko, Strobl, Matzler & De Massis, 2020; Zhao & Wang, 2020) analyzing the relationship between strategic flexibility and business model practices and enterprise performance.

Recommendations and Conclusion

Microenterprises are considered the backbone of the Malaysian economy. A major population of 99.2% registered businesses in Malaysia comprises SMEs, out of which 80% were microenterprises. National SME Development Council of Malaysia (NSDC) defined MEs based on two areas of measures: (1) number of employees and (2) annual sales turnover. A microenterprise in service sector refers to “a setup with full-time employees of less than five (5) or with annual sales turnover of less than RM300,000” (Department of Statistic Malaysia, 2019). However, these microenterprise facing issues related to business model practices and lack of employees’ knowhow in implementing them. Likewise, that is one of the major sources leading to low productivity and performance. This research based on review of literature suggest that microenterprises should adopt business model (BM) practices such as (product, customer interface, infrastructure management and financial aspects) and to enhance their performance and overall productivity. Business coaching and training can be used update employee’s knowledge and skill level.

References

- Abdelkarim, A. (2018). Toward establishing entrepreneurship education and training programmes in a multinational Arab university. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 7(1), 1-9.

- Ahmad, N.H., & Seet, P.S. (2009). Dissecting behaviours associated with business failure: A qualitative study of SME owners in Malaysia and Australia. Asian Social Science, 5(9), 98.

- Ajibefun, I.A., & Daramola, A.G. (2003). Determinants of technical and allocative efficiency of micro-enterprises: Firm?level evidence from Nigeria. African development review, 15(2?3), 353-395.

- Akbar, F., Omar, A., Wadood, F., & Al-Subari, S.N.A. (2017). The Importance of Smes, And Furniture Manufacturing SMEs in Malaysia: A review of literature.

- Al Mamun, A., & Ibrahim, M.D. (2018). Development initiatives, micro-enterprise performance and sustainability. International Journal of Financial Studies, 6(3), 74.

- Amoah, S.K., & Amoah, A.K. (2018). The role of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) to Employment in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Economics Research, 7(5), 151-157.

- Ayyagari, M., Beck, T., & Kunt, A. (2007). Small and medium enterprises across the globe. Small business economics, 29(4), 415-434.

- Bican, P.M., & Brem, A. (2020). Digital business model, digital transformation, digital entrepreneurship: Is There a Sustainable "Digital"? Sustainability, 12(13), 5239.

- Chin, Y.W., & Lim, E.S. (2018). SME Policies and Performance in Malaysia.

- Clauss, T., Abebe, M., Tangpong, C., & Hock, M. (2019). Strategic agility, business model innovation, and firm performance: an empirical investigation. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management.

- Cucculelli, M., & Bettinelli, C. (2015). Business models, intangibles, and firm performance: Evidence on corporate entrepreneurship from Italian manufacturing SMEs. Small Business Economics, 45(2), 329-350.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), (2020/2021). “Report of Special Survey ‘Effects of COVID-19 on the Economy and Companies/Business Firms’- Round 1 [Accessed: December 2020].

- Dijkstra, H., Van Beukering, P., & Brouwer, R. (2020). Business models and sustainable plastic management: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cleaner Production, 120967.

- Doran, J., McCarthy, N., & O’Connor, M. (2018). The role of entrepreneurship in stimulating economic growth in developed and developing countries. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6(1), 1442093.

- Flammini, S., Arcese, G., Lucchetti, M.C., & Mortara, L. (2017). Business model configuration and dynamics for technology commercialization in mature markets. British Food Journal.

- Foss, N.J., & Saebi, T. (2017). Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? Journal of Management, 43(1), 200-227.

- Genty, K., Idris, K., Wahat, N.W.A., & Kadir, S.A. (2015). Demographic factors and entrepreneurial success: A conceptual. International Journal of Management, 6(8), 366-374.

- Geremewe, Y.T. (2018). The role of micro and small enterprises for poverty alleviation. International Journal of Research Studies in Agricultural Sciences, 4(12), 1-10.

- He, C., Lu, J., & Qian, H. (2019). Entrepreneurship in China. Small Business Economics, 52(3), 563-572.

- Hodapp, D., Remane, G., Hanelt, A., & Kolbe, L.M. (2019). Business models for internet of things platforms: Empirical development of a taxonomy and archetypes.

- Jamak, A.B.S.A., Ibrahim, M.Y., Salleh, R., & Noor, A.M. (2014). Marketing and financial competencies of Malaysian Malays micro-entrepreneurs. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, 5(3), 218.

- Khan, S.J.M., & Anuar, A.R. (2018). Access to finance: Exploring barriers to entrepreneurship development in SMEs. In Global Entrepreneurship and New Venture Creation in the Sharing Economy, 92-111, IGI Global.

- Kotha, R., Lin, Y., Corboz, A.V., & Vissa, B. (2019). Does management training help entrepreneurs grow new ventures? Field experimental evidence from Singapore.

- Li, C., Ahmed, N., Khan, S.A.Q.A., & Naz, S. (2020). Role of business incubators as a tool for entrepreneurship development: The mediating and moderating role of business start-up and government regulations. Sustainability, 12(5), 1822.

- Miroshnychenko, I., Strobl, A., Matzler, K., & De Massis, A. (2020). Absorptive capacity, strategic flexibility, and business model innovation: Empirical evidence from Italian SMEs. Journal of Business Research.

- Mor, S., Madan, S., Archer, G.R., & Ashta, A. (2020). Survival of the smallest: A study of microenterprises in Haryana, India. Millennial Asia, 11(1), 54-78.

- Muhammad, M.Z., Char, A.K., Yasoa, M.B., & Hassan, Z. (2010). Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) competing in the global business environment: A case of Malaysia. International Business Research, 3(1), 66-75.

- Munoz, J.M., Welsh, D.H., Chan, S.H., & Raven, P.V. (2015). Microenterprises in Malaysia: a preliminary study of the factors for management success. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(3), 673-694.

- Muridan, M., & Ibrahim, P. (2018). A review of financing issues among microenterprises in Malaysia. Advanced Science Letters, 24(6), 4661-4665.

- Negrete-García, A.K. (2018). Constrained potential: A characterisation of Mexican microenterprises.

- Nielsen, C., Lund, M., Montemari, M., Paolone, F., Massaro, M., & Dumay, J. (2018). Business models: A research overview. Routledge.

- Omoruyi, E.M.M., Olamide, K.S., Gomolemo, G., & Donath, O.A. (2017). Entrepreneurship and economic growth: Does entrepreneurship bolster economic expansion in Africa. Journal Socialomics, 6(4), 219.

- Pillai, D., & Dam, L. (2017). Assessment of value proposition drivers for a micro enterprise.

- Purusottama, A., Trilaksono, T., & Soehadi, A.W. (2018). Community-based Entrepreneurship: A community development model to boost entrepreneurial commitment in rural micro enterprises. MIX: Scientific Journal of Management, 8(2), 429-448.

- Rahman, M.R. (2017). Micro-enterprises–marketing skills and strategies.

- Rahman, N.A., Yaacob, Z., & Radzi, R.M. (2016). The challenges among Malaysian SME: A theoretical perspective. World, 6(3), 124-132.

- Rahmawati, S. (2018). Analysis of the determinants of micro enterprises graduation. Journal of Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance, 113(6219), 1-49.

- Razak, D.A., Abdullah, M.A., & Ersoy, A. (2018). Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in turkey and malaysia a comparative discussion on issues and challenges. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law, 10(49), 2-591.

- Maksum, R.I., Rahayu, Y.S.A., & Kusumawardhani, D. (2020). A social enterprise approach to empowering Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Indonesia. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(3), 50.

- Shafi, M., Yang, Y., Khan, Z., & Yu, A. (2019). Vertical co-operation in creative micro-enterprises: A case study of textile crafts of Matiari District, Pakistan. Sustainability, 11(3), 920.

- Šimberová, I., & Kita, P. (2020). New business models based on multiple value creation for the customer: A case study in the chemical industry. Sustainability, 12(9), 3932.

- SME Corp report (2019). Guideline for new SME definition. SME Corp. Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

- SME Corp. Malaysia (2019). SME's Annual Report. Retrieved on August 25th, 2018 at https://www.smecorp.gov.my/index.php/en/laporan-tahunan/3911-sme-annual-report-2018-2019

- SME Corp. Malaysia (2021). SME's Annual Report. Retrieved on May 5, 2021, at https://www.smecorp.gov.my/index.php/en/resources/2015-12-21-11-07-06/sme-corp-malaysia-annual-report

- SME Corp. Malaysia (2021). SME's Annual Report. Retrieved on May 5, 2021, at https://www.smecorp.gov.my/index.php/en/resources/2015-12-21-11-03-46/malaysia-weekly-economic-news

- SME Corp. Malaysia (2021). SME Insights 2019/20 New Release Retrieved on May 5, 2021, at https://www.smecorp.gov.my/index.php/en/component/content/article/191-laporan-tahunan/4323-sme-insights-2019-20?layout=edit

- Tahir, H.M., Razak, N.A., & Rentah, F. (2018). The contributions of small and medium enterprises (SME’s) On Malaysian economic growth: A sectoral analysis. In International Conference on Kansei Engineering & Emotion Research, 704-711, Springer, Singapore.

- Thaker, M.A.B.M.T. (2018). A qualitative inquiry into cash waqf model as a source of financing for micro enterprises. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance.

- Commission of the European Communities (2003). Commission recommendation concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. Official Journal of the European Union.

- U.S. Small Business Administration (2010). Program for investment in microentrepreneurs act Available at http://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/files/serv_fa_2010_ primetrack123.pdf

- Verdugo, G.A.B. (2018). Innovative self-concept of micro-entrepreneurs: Perception of Barriers and Intention to Invest. BAR-Brazilian Administration Review, 15(2).

- Wang, G., Li, L., & Jiang, X. (2019). Entrepreneurial business ties and new venture growth: The mediating role of resource acquiring, bundling and leveraging. Sustainability, 11(1), 244.

- Zhao, Y., & Wang, X. (2020). Organisational unlearning, relearning, and strategic flexibility: from the perspective of updating routines and knowledge. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 1-13.