Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 6

Public Procurement Regulation: Increasing Developing Integration in Asean

Siwarut Laikram, Walailak University

Shubham Pathak, Walailak University

Abstract

The efforts and accession to public procurement agreement will be more secure and enhance higher value for spending budget of developing countries. The correlation among developing countries in Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is difficult to contemplate due to the trade discrimination of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) which eliminate the foreign tender. Therefore, effective policy implementation will put forward the growth of transparency, competitiveness and accountable government procurement systems that may encourage Government Procurement Agreement’s (GPA’s) accession of developing countries. The methodology adopted involves the Matrice d'impacts croisés multiplication appliquée á UN classment (MICMAC) methodology with the factors selected through the Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM), excerpts from experts, literature review and Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM). To analyse advantages and challenges effectively, a competitive approach and socio-legal methodology is adopted to analyse trade and policy implications along with the GPA. Also, concluding with the limited hope that the accession to GPA in developing countries will be a hard lesson for ASEAN market accesses.

Keywords

Government Procurement Agreement, World Trade Organization, Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM), Fuzzy Delphi Method, Matrice D'impacts Croisés Multiplication Appliquée Á UN Classment (MICMAC).

Introduction

The International Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) adopted the revised GPA on 30th March 2012 at World Trade Organization (Anderson & Müller, 2015). Since 1997, the objective was to open up the government procurement market as much as possible to international competition. However, accession to the Government Procurement Agreement may have been a difficult decision for several developing countries. This mainly results from the fear and hesitation that the accession could have led to an impact on the local industries and the economy may have easily collapsed in developing countries. Thus, many developing countries choose to avoid the accession of Government Procurement Agreement. It is claimed that industries' development would be negatively affected when competing internationally (Yukins & Schnitzer, 2015).

Furthermore, some developing countries have remarked observations as to whether or not it would be a recognizable advantage. Moreover, developing countries faced similar barriers when they had to make a difficult decision about joining the Government Procurement Agreement (Anderson & Müller, 2015). Nevertheless, while looking forward to developing countries’ decisions, it must be said that the consent decision to be bound in Government Procurement Agreement was appropriate for developing countries, even if, it is hard to measure the profit from the accession to the Government Procurement Agreement extensively. Thus, this article aims to discuss the context of the International Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) in terms of WTO law. It also analyses the challenges of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) accession that has been beneficial to developing countries from ASEAN perspectives (Gourdon & Bastien, 2019).

Literature Review

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is a multilateral member operated and controlled organization, which came into force on the 1st of January 1995. The purpose of the WTO is to increase standards of living, reduce unemployment, reduce poverty, enhance income, and build an effective infrastructure and expand production of trade in goods and services. According to the provisions of the WTO Agreement, in order to reach their goals, the organization has to consider the protection and conservation of the natural environment and also the demands of developing countries. There are two mechanisms by which WTO can succeed in its goals. First of all, the market has accessibility as one of the measures that handle the reduction of tariffs and non-tariffs barriers. Secondly, the principles of non-discrimination among Most Favored Nation (MFN) and National Treatment (NT). Hence, WTO members increase trade liberalisation within the WTO member countries in all areas of industries (WTO, 2020). The WTO Agreement covers a series of agreements which are equally binding and enforceable between all WTO members. However, the Annex of the WTO Agreement can be classified into two agreements. First, the multilateral agreements are bound by all acceding members such as General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) and General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). On the contrary, the Plurilateral Agreements are negotiated within the WTO, however, the content of application is limited to those members who have already applied as members of those specific agreements. These agreements are given in Annex of the WTO Agreement such as Agreement on Government Procurement, Agreement on Trade in Civil Aircraft, International Bovine Meat Agreement and International Dairy Agreement (Oteo, 2012).

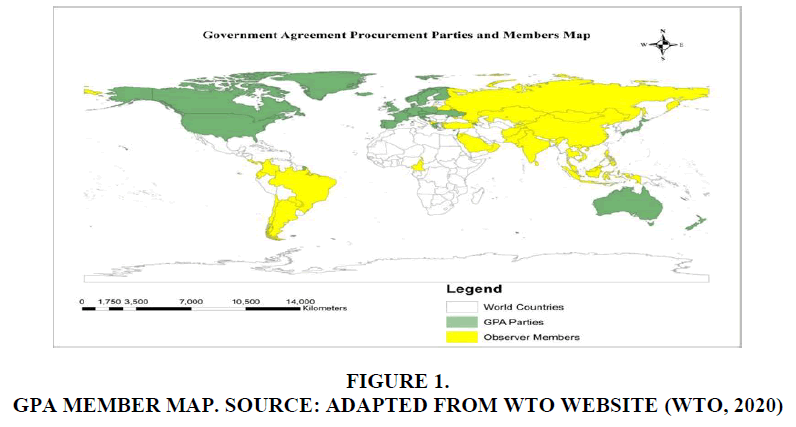

Regarding the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA), it is a plurilateral agreement within the framework of the World Trade Organisation. Currently, there are 164 members of the WTO (Figure 1), from those only forty-eight countries are members of the GPA divided into 21 parties (Table 1). These GPA’s party countries comprise of Armenia, Australia ,Canada, the European Union, Hong Kong, Iceland; Israel, Japan, Republic of South Korea, Liechtenstein, Republic of Moldova, Montenegro , Netherlands with respect to Aruba, New Zealand ,Norway, Singapore, Switzerland, Chinese Taipei, Ukraine, United Kingdom and United States (WTO, 2020). Another thirty-five WTO members participate in the Government Procurement Agreement Committee under “observer’s status” of this Agreement (Table 2).

| Table 1 List of Government Procurement Agreement’s Members. | |||

| Parties | Members | Date of entry into force/accession | |

| GPA 1994 | Revised GPA | ||

| 1. | Armenia | 15 September 2011 | 6 June 2015 |

| 2 | Australia | 5 May 2019 | 5 May 2019 |

| 3. | Canada | 1 January 1996 | 6 April 2014 |

| 4. | European Union with regard to its 27 member states | 6 April 2014 | |

| Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden | 1 January 1996 | ||

| Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovak Republic and Slovenia | 1 May 2004 | ||

| Bulgaria and Romania, | 1 January 2007 | ||

| Croatia | 1 July 2013 | ||

| 5. | Hong Kong , China | 19 June 1997 | 6 April 2014 |

| 6. | Iceland | 28 April 2001 | 6 April 2014 |

| 7. | Israel | 1 January 1996 | 6 April 2014 |

| 8. | Japan | 1 January 1996 | 16 April 2014 |

| 9. | Republic of Korea | 1 January 1997 | 14 January 2016 |

| 10. | Liechtenstein | 18 September 1997 | 6 April 2014 |

| 11. | Republic of Moldova | 14 July 2016 | 14 July 2016 |

| 12. | Montenegro | 15 July 2015 | 15 July 2015 |

| 13. | Netherlands with respect to Aruba | 25 October 1996 | 21 August 2014 |

| 14. | New Zealand | 12 August 2015 | 12 August 2015 |

| 15. | Norway | 1 January 1996 | 6 April 2014 |

| 16. | Singapore | 20 Oct 1997 | 6 April 2014 |

| 17. | Switzerland | 1 January 1996 | Pending |

| 18. | Chinese Taipei | 15 July 2009 | 6 April 2014 |

| 19. | Ukraine | 18 May 2016 | 18 May 2016 |

| 20. | United Kingdom | 1 January 1999 | 1 January 2021 |

| 21. | United States | 1 January 1996 | 6 April 2014 |

| Table 2 List of Observer Countries Among WTO Members | ||

| Number | Observer Members | Date of acceptance by Committee as observers |

| 1. | Afghanistan | 18 October 2017 |

| 2. | Albania* | 2 October 2001 |

| 3. | Argentina | 24 February 1997 |

| 4. | Bahrain | 9 December 2008 |

| 5. | Belarus | 27 June 2018 |

| 6. | Brazil* | 18 October 2017 |

| 7. | Cameroon | 3 May 2001 |

| 8. | Chile | 29 September 1997 |

| 9. | China * | 21 February 2002 |

| 10. | Colombia | 27 February 1996 |

| 11. | Costa Rica | 3 June 2015 |

| 12. | Ecuador | 26 June 2019 |

| 13. | Georgia * | 5 October 1999 |

| 14. | India | 10 February 2010 |

| 15. | Indonesia | 31 October 2012 |

| 16. | Jordan * | 8 March 2000 |

| 17. | Kazakhstan* | 19 October 2016 |

| 18. | Kyrgyz Republic * | 5 October 1999 |

| 19. | Malaysia | 18 July 2012 |

| 20. | Mongolia | 23 February 1999 |

| 21. | North Macedonia* | 27 June 2013 |

| 22. | Oman * | 3 May 2001 |

| 23. | Panama | 29 September 1997 |

| 24. | Pakistan | 11 February 2015 |

| 25. | Paraguay | 27 February 2019 |

| 26. | Philippines | 26 June 2019 |

| 27. | Russian Federation * | 29 May 2013 |

| 28. | Saudi Arabia | 13 December 2007 |

| 29. | Seychelles | 16 September 2015 |

| 30. | Sri Lanka | 23 April 2003 |

| 31. | Tajikistan* | 25 June 2014 |

| 32. | Thailand | 3 June 2015 |

| 33. | Turkey | 4 June 1996 |

| 34. | Viet Nam | 5 December 2012 |

The fundamental objective of this research is to ascertain, analyze and recommend towards accession of Government Procurement Agreement (GPA). The GPA is to open government procurement markets among its parties which rely on three secondary objectives as follows;

1. Ascertain the fairness and equal opportunity through accession to GPA.

2. Analyzing benefits of non-discrimination among Most Favored Nation (MFN) and National Treatment (NT).

3. Recommend towards accession of the GPA among developing nations in ASEAN to adequately utilize integration.

In general, under the rules of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (WTO, 1968), the government procurement was included in the rules on market access principle and non-discrimination. Nevertheless, in Article III:8 (a) on national treatment obligation under the plurilateral 1994 claims that The provisions of this Article shall not apply to laws regulations or requirements governing the procurement by governmental agencies of products purchased for governmental purposes and not with a view to commercial resale (WTO, 1994). Hence, there is abiding obligation that the subsequent practice from the GPA members illustrates, the Most Favored Nation (MFN) treatment obligation was excluded. In addition, Article XIII GATS also explicitly excludes government procurement from the GATS. This is a reason why the government procurement has still been excluded from the scope of application of the GATT 1994 and GATS, even though negotiations on this issue were postponed in the WTO many times in the past. However, an agreement was never reached within the WTO regarding this lack of consensus during the Ministerial Conference since 1994. The next step forward for market access to public procurement markets was only to be reached through within a plurilateral agreement with the perspective that its privileges and advantages would bring other WTO members to join GPA. The first plurilateral public procurement agreement was named the “Tokyo Code”. It was concentrated on during the Tokyo round within the model of the former GATT 1947 and entered into enforcement on 1st January 1981 (Oteo, 2012). From that time, this agreement has been amended frequently until the new provisions have been appended. Finally, there was an amendment that was related in the Uruguay round of negotiations in January 1994 which played a crucial part in causing the first Government Procurement Agreement.

Methodology

This research implies the mixed method approach with qualitative method involving the socio-legal methodology and quantitative method involving the MICMAC methodology.

The Socio-legal methodology is a view of human behaviour that concerns the form of relationships among individuals (Levin & Levin, 1991). At the end of the nineteenth century, the development of Socio-legal methodology has been applied to law. It is also well known in the name of sociological jurisprudence (Freeman, 1994). This jurisprudence would be a perspective in law that uses sociological theory to analyse human relationships and behaviours because the nature of humans is that they need to live together in a good society. Jhering states that “the function of law as an instrument for serving the needs of human society” (Freeman, 1994). There always have the conflictions between people because of an individual need which differences from each other. So, the legal system was built for managing the benefits argument in society (Friedman, 1986).

In terms of the qualitative findings, To enlarge the scope of legal sociology perspective, World Bank report is applied for better understanding of sociology interpretation along with the public procurement agreement of WTO that was based on the identified strengths and weaknesses of member nations (Brack, 2014). The report predicts governments around the world spending approximately US$9.5 trillion for public contracts every year. This signifies that on average, public procurement constitutes around 6% to 20% of member country’s Gross Domestic product (GDP) (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016 & 2021). Therefore, the strengthening of public procurement systems is essential to achieve concrete and sustainable results and to build effective procurement. Considering these implementations, the empirical section of this study is included in the socio-legal methodology and case study of the World Bank is chosen which is related with the socio-legal development and collaborations in the ASEAN economy. Therefore, these efforts are focused on creating the foundation for an adequate and effective public procurement agreement of WTO through establishing a legal, regulatory and institutional framework among the ASEAN developing countries.

Public procurement competitions are legal processes that deal the balance an individual interest and maintenance of the public society meanwhile, the conflict of public procurement interest must be managed and defined by law since the law as a social engineering tool (Kimball & Coquillette, 2020; Patterson, 1960). This means that the key is to balance these interests and reconcile the transparency and competition of public procurement. Furthermore, Adam Smith (Abdurakhmanova et al., 2020) believes that economic growth is the result of an increase in human capital. Therefore, the intense public procurement competition would become more productive when procurement market mechanism functions are effectively and freely (Auriol et al., 2016). The various competitors rapidly outside the same market will be more competitive and transparent to provide a better quality of commodities for the governments (Awoke & Singh, 2020). As a consequence, governments will gain higher quality products at an affordable and reasonable price range. The question is that what are the efforts and accession to public procurement regulation towards the globalization and whether the international public procurement agreement of WTO has stimulated the growth of transparency, competitiveness and further the result of economic and social development (Haugen & Solberg, 2010).

This research provides for critical factors towards the non-member of GPA countries in order to enhance their accession in GPA. The methodology adopted involves the MICMAC methodology with the factors selected through the interpretive structural modeling, experts, literature review and Fuzzy Delphi method. The literature review provided for fifteen factors which are directly affecting the non-member GPA countries including Government budget security (WTO, 2012), D value-0.632; Cooperation (Dennis, 2003), D value-0.654; Transparency (WTO, 1968) D value-0.581; Opportunity (WTO, 1994), D value-0.425; Non-discrimination (WTO, 2020) D value-0.6125; Accession (WTO, 2020) D value-0.695; Benchmark (World Bank, 2016) D value-0.325; Corruption (World Bank, 2016) D value-0.154; Efficiency (Arrowsmith et al., 2000) D value-0.387; Development (Price, 2017) D value-0.639; Conciliation (Padhi & Mohapatra, 2011) D value-0.384; Accountability (Awoke & Singh, 2020) D value-0.469; Human resource (Rickard & Kono, 2014) D value-0.563; Collaboration (Georgopoulos et al., 2017) D value-0.647; Integration (WTO, 1994) D value-0.618 respectively with threshold of 0.060.

These factors were cross examined in several literatures and are narrowed down to seven factors for the interpretive structural modeling through adoption of fuzzy Delphi method due to the fact that higher number of factors complicates the model (Attri et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2019). These factors included Government budget security, Cooperation, Non-discrimination, Accession, Development, Collaboration and Integration respectively.

The respondents involved thirty respondents involving experts such as policy makers, lawyers, judges, university faculty, researchers and international organizations and were contacted with questionnaire (Table 3). With a response rate of 90%, 27 questionnaires were found to be valid.

| Table 3 Profile of the Respondents | |||||

| Serial Number | Designation | Sector | Professional expertise | Education level | Age group |

| 1 | Lawyers | Legal | International law | Masters | 40-50 |

| 2 | Diplomat | Administration | ASEAN law | Masters | 40-50 |

| 3 | University professor | Education | International law | PhD. | 50-60 |

| 4 | University lecturer | Education | ASEAN law | PhD. | 30-40 |

| 5 | Judges | Legal | ASEAN law | Masters | 40-50 |

| 6 | Researchers | Research | Trade Law | Masters | 20-30 |

| 7 | Policy makers | Administration | ASEAN law | Masters | 40-50 |

| 8 | Lawyers | Legal | ASEAN law | Masters | 40-50 |

| 9 | Lawyers | Legal | Civil Law | Masters | 30-50 |

| 10 | Policy makers | Administration | ASEAN law | Masters | 40-50 |

The respondents provided for the expertise and assessed all the 15 factors. A total of seven factors were selected through these assessments and fuzzy Delphi method with a threshold value of 0.60. The ISM is utilize to ascertain the relationships between variables (Warfield, 1974). On the basis of the expert’s inputs, the structural self-interaction matrix was formulated defining the comparative pairs as S: Factor a significantly impacts factor b; G: Factor b significantly impacts factor a; Y: Factors a and b significantly impacts each other; Z: Factor a and b have no significant correlation (Table 4).

| Table 4 SSIM Matrix | |||||||

| Factors | F1 | F2 | F5 | F6 | F10 | F14 | F15 |

| F1 | 1 | G | Z | G | Z | G | G |

| F2 | 1 | Y | S | Y | S | G | |

| F5 | 1 | S | Y | S | G | ||

| F6 | 1 | G | S | G | |||

| F10 | 1 | S | G | ||||

| F14 | 1 | G | |||||

| F15 | 1 | ||||||

The model adopted for this research provided for the factors responsible towards the accession of the GPA by the non-member countries. These values were then transformed into binary values i.e. 0 and 1 depending upon the relationships between the factors (Table 5).

| Table 5 Conversion Table from SSIM to IRM | ||

| SSIM Values | Binary conversion | |

| (a, b) | (b, a) | |

| S | 1 | 0 |

| G | 0 | 1 |

| Y | 1 | 1 |

| Z | 0 | 0 |

This provided for the contextual relationship between the selected seven factors. The result was analyzed in terms of the IRM matrix (Table 6).

| Table 6 IRM Matrix | |||||||

| Factors (Fa) | Factors (Fb) | ||||||

| F1 | F2 | F5 | F6 | F10 | F14 | F15 | |

| F1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| F5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| F6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| F10 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| F14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| F15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

The transitivity between factors has been ascertained and depicts the contextual relationship between each two factors among the seven selected factors. This provides for the FRM matrix and driving and dependence power among the selected factors (Table 7).

| Table 7 FRM Matrix | ||||||||

| Factors (Fa) | Factors (Fb) | Driving Power | ||||||

| F1 | F2 | F5 | F6 | F10 | F14 | F15 | ||

| F1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| F2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| F5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| F6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| F10 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| F14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| F15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Dependence | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 28 |

The reachability, antecedent and intersection sets are derived through level partitions to provide for the interaction matrix. These levels provide for the hierarchical structures of each factor among the chosen seven factors (Table 8).

| Table 8 Level Partition Interaction Matrix | ||||

| Factors | Reachability set R (Fa) | Antecedent set C ( Fa) | Intersection set between R(Fa) and C(Fa) | levels |

| F1 | F1 | F1, F2, F5, F6, F10, F14, F15 | F1 | 1 |

| F2 | F4, F5, F10 | F4, F5, F10, F15 | F4, F5, F10 | 4 |

| F5 | F4, F5, F10 | F4, F5, F10, F15 | F4, F5, F10 | 4 |

| F6 | F6 | F4, F5, F6, F10, F15 | F6 | 3 |

| F10 | F4, F5, F10 | F4, F5, F10, F15 | F4, F5, F10 | 4 |

| F14 | F14 | F4, F5, F6, F10, F14, F15 | F14 | 2 |

| F15 | F15 | F15 | F15 | 3 |

The Matrice d'impacts croisés multiplication appliquée á un classment (MICMAC) methodology has been used in several previous studies and have been providing analyzed selection of the factors Table 9 (Karmaker et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2019).

| Table 9 Factors According to their Micmac Ranks | ||||

| Factors | Driving Power | Dependence | Driving Power/ Dependence | MICMAC ranking |

| F1 | 1 | 5 | 0.2 | 7 |

| F2 | 6 | 4 | 1.5 | 2 |

| F5 | 5 | 4 | 1.25 | 3 |

| F6 | 3 | 4 | 0.75 | 5 |

| F10 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| F14 | 4 | 6 | 0.67 | 6 |

| F15 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

The MICMAC ranking were further analyzed in order to achieve the final matrix with each selected factor and its individual or group impact upon the accession choice and decision making of the non GPA member countries (Table 10).

| Table 10 Micmac Analysis of the Factors | |||||||

| Driving power | Zone 3 | Zone 4 | |||||

| 6 | F2 | ||||||

| 5 | F15 | F5 | |||||

| 4 | F10 | F14 | |||||

| 3 | F6 | ||||||

| 2 | |||||||

| 1 | F1 | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Zone 1 | Zone 2 | ||||||

| Dependence Power | |||||||

The above analysis of the selected seven factors depicts that there is no autonomous factor. The diagram explains that F1 and F6 in the zone 2 are dependent variables and are among the lower levels of the driving power. Similarly, F15 has been determined as the linking factor and influence significantly all the selected factors. However, the factors, F2, F5, F10 and F14 are found to be among highest driving power and should be among the decidedly considering factors.

The results from the MICMAC model adopted for the study depicted the absence of any single autonomous factor existing. The dependent variables are found to be F1 (Government budget security) and F6 (Accession) which are shown in Zone Two (Refer Table 8). It was found that the F15 (Integration) factor is the linkage factor and provides for the amalgamating effect of all the other factors in order to enhance the accession by the non-member countries. Similarly, in Zone 4 the factors with highest driving power are F2 (Cooperation), F5 (Non-discrimination), F10 (Development) and F14 (Collaboration). These factors have cascading effects upon the other factors to incline towards the accession of the GPA.

Discussion

Regarding the benefits of developing countries' accession, it is known that the GPA in WTO is an important international legal instrument in encouraging procurement market competition, providing public transparency, stimulating integrity and upholding money for currency movements in domestic procurement systems. Thus, the benefits of developing countries for joining the GPA are clear.

First of all, the proof and guarantee that the spending budget of developing countries’ governments are secured within the law. The government procurement will be safer and better value for money spent by the government on its procurement. As a result of more tenders, competition will increase efficiency, transparency, clear procedures, accountability and due process by giving fair market value and equal opportunities. Thus, the GPA will help to reduce corruption and increase an effective mechanism for sparing finances in the procurement regime (Mavroidis & Sapir, 2021; Osei-afoakwa, 2013).

The second benefit is the significant cooperation, collaboration and integration of the GPA provisions that prohibits the non-discrimination principle in tender judgment according to MFN and NT principle in GATT. Both principles have been consented to be bound by the agreement. In addition, it is normally observed that the GPA provisions would contribute many advantages. If there is a large number of a tender, it will lend more competition to the procurement market. As a consequence, the bidder who submits the lowest bid for the government’s project will become a tender. There are some reports of the panel, which have claimed that when a government bans procurement discriminated products, this causes impact to the imported products that flow to domestic countries because the domestic products are relied on by the domestic government (McCrudden & Gross, 2006). In other words, the government does not need to pay the inflated price between the same products because the government’s procurement auctions can lead to various effects. As we can observe that encouraging the international tenders to auctions, it would help non-discrimination between domestic tenders and foreign tenders (Knight et al., 2012).

Thirdly, the non-discrimination among legal activities and in the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) in terms of theory, practice, procedure and regulations are of critical importance. All of these factors in government procurement will motivate procurement agencies for implementing non-discriminatory, timely, and effective procedures in developing countries. Therefore, the process would allow developing countries to have more standard measures. However, it has been seen that both domestic tenders and foreign companies will be impacted directly by reduced costs of procurement (McCrudden & Gross, 2006; Shilungu, 2020).

Fourthly, as an accession to the GPA, a majority of developing countries would have benefits, development and an opportunity to access the other GPA members' markets equally, as it would guarantee the accession to the procurement markets. For example, in 2009, the participation of Chinese Taipei for joining GPA members has increased procurement opportunities by approximately more than $20 billion per year, although, some developing countries have a restriction to access the procurement markets of larger GPA members such as, the US, the EU and China as suppliers (Anderson & Müller, 2015).

Conclusion

It has been acknowledged that the international Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) is all inclusive for international procurement. In order to accomplish the public procurement’s goal, the procurement markets should provide free competition and transparency. Even though, nowadays only 48 parties joining this Government Procurement Agreement but it seems that an effective system and challenge for the international world community should gather the procurement regulations in order to avoid the corruption problems. Particularly, the current Government procurement problems in developing countries still occur and this poses the question whether membership in the GPA would assist in ridding corruption. Many people think that the greater transparency in international government procurement would benefit developing countries. Time has to be given to developing countries in order to allow many complex preparatory steps that are required to determine the developing countries' comparative advantages, and encourage domestic suppliers to adjust during the reformation and transition.

At this time, the new GPA’s framework will create a new mechanism for international public procurement in the future. As a result, the revised GPA is used in a way that it might grant a flexible application of the agreement to developing countries. Hence, it would ultimately depend on the policy decision-making that those developing countries make such parties to the Government Procurement Agreement are willing to proceed with this plurilateral GPA system, as well as ,the combinations of bilateral form or regional trade agreements, thus, not only considering fairness, integrity and efficiency for any accession of the GPA, but also regarding reasonable interpretations that may occur in the advantages, costs and challenges of GPA accession for developing countries.

The paper presents the current scenario of the GPA and its implications upon the developing and ASEAN countries. However, the future research could focus upon in-depth analysis of adequate legal measures, exploration of new procurement technologies, and possible procurement processes which would support international agreements for the sustainable economic development of ASEAN nations. For instance, e-procurement system which would reduce costs for bidders, on the other hand, the procurement laws should be synchronized for the transparent and unbiased procurement.

In conclusion, each GPA party has the right to access the other developing countries' members in other procurement markets (Rawat, 2021). In general, some developing sectors of the economy are influenced by the public government. For example, purchasing the military weapon contract by the government procurement should be legalized since many developing countries do not have enough experience in those areas. This prevalent in most of the developing countries in the ASEAN region (Wyatt & Galliott, 2020). Thus, ASEAN member nations need more time to prepare and protect their development, economy and industrial sectors of the economy for developing countries throughout the integration and collaborative processes in public procurement. In addition, this effect would encourage domestic companies to run their business openly. Meanwhile, the domestic public procurement competition would gain a lot of benefits from goods and services because they are forced by International tenders. Hence, domestic companies have to improve the quality and value of products as a result of foreign competition. Therefore, developing countries in ASEAN would not only get the benefits from the quality of product value, enhanced employability, foreign investment, improved infrastructural facilities, strengthened regional trade agreements but also transfer of new technology from the originator to a secondary user, especially from developed countries to less developed countries in an attempt to boost their procurement economies.

References

- Abdurakhmanova, G., Shayusupova, N., Irmatova, A., & Rustamov, D. (2020). The role of the digital economy in the development of the human capital market. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 24(7), 8043–8051.

- Anderson, R., & Müller, A. (2015). The revised WTO agreement on government procurement: An emerging pillar of the world trading system: Recent Developments. Trade, Law and Development, 7(1), 42–63.

- Arrowsmith, S., Linarelli, J., & Wallace, D. (2000). Regulation public procurement-national and international perspectives. Kluwer Law International BV. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.th/books?hl=en&lr=&id=z4ZiG7rS2FMC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=Arrowsmith,+S.,+Linarelli,+J.,+%26+Wallace,+D.+(2000).+Regulation+Public+Procurement-National+and+International+Perspectives.+Hauge:+Kluwer+Law+International+BV.&ots=m-iBUl8VeG&si

- Attri, R., Dev, N., & Sharma, V. (2013). Interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach: An overview. Research Journal of Management Sciences, 2319(2), 1171-1194.

- Auriol, E., Straub, S., & Flochel, T. (2016). Public procurement and rent-seeking: The case of paraguay. World Development, 77(1), 395–407.

- Awoke, T., & Singh, A. (2020). Transparency, accountability and efficiency in public procurement practices (the case of public higher educational institutions in Ethiopia). Studies in Indian Place Names, 40(3), 2965–2985.

- Brack, D. (2014). Promoting legal and sustainable timber: Using public procurement policy. Chatham House.

- Dennis, D.J. (2003). Developing indicators of ASEAN integration a preliminary survey for a roadmap authors.

- Freeman, M.D. (1994). Lloyd’s introduction to jurisprudence. Sweet & Maxwell.

- Friedman, L.M. (1986). The law and society movement. Stanford Law Review, 21(1), 763–780.

- Georgopoulos, A., Hoekman, B.M., & Mavroidis, P.C. (2017). The internationalization of government procurement regulation. Oxford University Press.

- Gourdon, J., & Bastien, V. (2019). Government procurement in ASEAN: Issues and how to move forward. In Regional Integration and Non-Tariff Measures in ASEAN.

- Haugen, K.K., & Solberg, H.A. (2010). The soccer globalization game. European Sport Management Quarterly, 10(3), 307–320.

- Karmaker, C.L., Ahmed, T., Ahmed, S., Ali, S.M., Moktadir, M.A., & Kabir, G. (2021). Improving supply chain sustainability in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in an emerging economy: Exploring drivers using an integrated model. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 26, 411–427.

- Kimball, B.A., & Coquillette, D.R. (2020). The perilous trials of roscoe pound and the faculty, 1916–1927. In The Intellectual Sword (pp. 118–156). Harvard University Press.

- Knight, L., Harland, C., Telgen, J., Thai, K.V., Callender, G., & McKen, K. (2012). Public procurement: International cases and commentary. Routledge.

- Levin, J., & Levin, W.C. (1991). Sociology of educational late blooming. Sociol Forum, 6(1), 661–679.

- Mavroidis, P.C., & Sapir, A. (2021). China and the WTO: Why multilateralism still matters. Princeton University Press.

- McCrudden, C., & Gross, S.G. (2006). WTO government procurement rules and the local dynamics of procurement policies: A Malaysian case study. European Journal of International Law, 17(1), 151–185.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2016). Methodology for Assessing Procurement Systems. Retrieved fromhttps://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/Methodology-Assessment-Procurement-System-Revised-Draft-July-2016.pdf0

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). Why assess your public. Retrieved fromhttps://www.mapsinitiative.org/about/2020-MAPS-brochure-EN.pdf?fbclid=IwAR28ZbBCoxyFltdXnOFSBRWHEzYd80Vg0BnQhgFPjIGvx3JSAcNATE2w9jc

- Osei-afoakwa, K. (2013). The antecedents and the prospects of public procurement regulation in Ghana. Developing Country Studies, 3(1), 123–136.

- Oteo, L.L. (2012). Challenges of international government procurement the revised GPA from a European perspective.

- Padhi, S.S., & Mohapatra, P.K.J. (2011). Detection of collusion in government procurement auctions. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 17(4), 207–221.

- Patterson, E.W. (1960). Roscoe pound on jurisprudence. Columbia Law Review, 60(8), 1124–1132.

- Price, D. (2017). Indonesia and the trans-pacific partnership agreement: The luxury of time. Indonesia Law Review, 7(1), 1-8.

- Rawat, S. (2021). WTO GPA and sustainable procurement as tools for transitioning to a circular economy table of contents. The George Washington University Law School.

- Rickard, S.J., & Kono, D.Y. (2014). Think globally, buy locally: International agreements and government procurement. Review of International Organizations, 9(3), 333–352.

- Shilungu, M. (2020). Tenderpreneurship?: Unintended consequences in the kenyan public procurement market.

- Tan, T., Chen, K., Xue, F., & Lu, W. (2019). Barriers to building information modeling (BIM) implementation in China’s prefabricated construction: An interpretive structural modeling (ISM) approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 219(1), 949–959.

- Warfield, J.N. (1974). Developing interconnection matrices in structural modeling. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 4(1), 81–87.

- World Bank. (2016). Benchmarking public procurement 2017: Assessing public procurement regulatory systems in 180 economies. Retrieved from https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/32500

- WTO. (1968). The general agreement on tariffs and trade. In World Trade Organization.

- WTO. (1994). Article XIII. Non-Discriminatory administration of quantitative restrictions. WTO - Trade in Goods.

- WTO. (2012). Agreement on government procurement (as amended on 30 March 2012). World Trade Organization.

- WTO. (2020). Basic purpose and concepts. World Trade Organization.

- WTO. (2020). Parties, observers and accessions. World Trade Organization.

- Wyatt, A., & Galliott, J. (2020). Closing the capability gap: Asean military modernization during the dawn of autonomous weapon systems. Asian Security, 16(1), 53–72.

- Yukins, C.R., & Schnitzer, S.J. (2015). GPA accession: Lessons learned on the strengths and weaknesses of the wto government procurement agreement. 7 Trade Law & Development Journal, 89(1), 1-9.