Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Regulatory Regime of Medicine in Malaysia

Nurul Hayati Bohari, University of Malaya

Abdul Samad Abdul Ghani, University of Malaya

Abstract

Different countries practise different regulatory regimes and structure of medicine. Thus, before any improvement is made on the regulation, people should first understand the regulatory regime of medicine with regard to medicine governance and regulation. Medicine governance is integral to health, economic, and socio-political sustainability. The management of medicine governance is complex, involving various regulations and requiring coordination across a range of professional bodies and relevant stakeholders so as to safeguard public interest. Therefore, this paper aims to identify the current regulatory regime of medicine regulatory enforcement in Malaysia as a developing country and analytically investigates it from the perspective of the responsive regulation theory. The method of analysis for this study involved library search of statutory laws or regulations, books, and annual reports produced by the relevant agencies. This study examined the regulatory regime, structure and classification of the regulatee groups in relation to the regulatory enforcement framework of Malaysia. Analytically, it was found that the current regulatory structure is inadequate where the composition of authorities is prone to represent public services and this significantly leads to inadequate representation and compliance from the regulatees. It is therefore suggested that future research examines the regulatory enforcement of medicine in Malaysia through the perspectives of the regulatees and the users to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the issue.

Keywords

Regulatory Regime, Law Enforcement, Medicine, Regulatee, Regulation

INTRODUCTION

Regulatory enforcement is a universal concern as it is an issue that is discussed globally. In addition, the work of a regulatory enforcement agency can easily be questioned and criticised as ineffective, weak and counterproductive. (McKay, 2003; Garuba, 2009; Pedersen, 2013). The criticism might be due to the regulatory context and the enforcement strategy or approach.

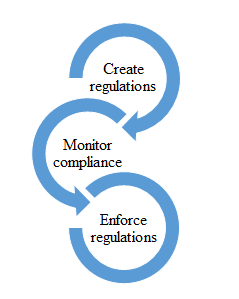

Indeed, there has been numerous research conducted to find answers to the big question on how to be an efficient 'regulator'. Many researchers such as Bardach & Kagan (1982); Scholz (1991); Grabosky (1994); Baldwin (2004) have investigated regulatory improvement and crafted models and theories from the findings of their research. Based on these researches, various regulatory enforcement frameworks have been formed and this resulted in diverse regulatory enforcement regimes being practised in different countries, fields of regulation and industries. Regulatory regime focuses on the ‘responsibilities’ of the parties involved in the regulatory enforcement process. Based on the regulatory process illustrated in Error! Reference source not found., the responsibilities of regulatory enforcement are on ‘creating regulation’ which is the setting of the regulations or rules, ‘monitoring compliance’ which is the level of monitoring in the conduct of the regulations (middle level) and on ‘enforcing regulations’ which is the level of implementation of the enforcement tasks (lowest level).

Before looking at the agency regulatory approaches and strategies, the regime of the regulatory enforcement agency should be determined. Typically, the regulatory enforcement regime is shaped by government regulations. The regulatory enforcement regime is generally based on the setting of the regulation, enforcement criteria and oversight, and the enforcement execution process (Heijden, 2009). The regulatory structure and the management of the agency would define and describe the regulatory regime where the implementation could either be public, prescribed co-regulation, conditional co-regulation, substitute co-regulation, or a private regime. In the responsive regulation theory, the encouragement is toward enforced self-regulation as one of the strategies (Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992).

Previous studies maintained that regulation needs a combination of strategies and multiple policies in the regulatory regime. Borner (2015) remarked that a country would show numerous positive impacts when the regulation adopted uses multiple or a combination of policy instruments. For example, in the regulatory enforcement of forests in the Amazon area, a combination of policy instruments is adopted in regulating the declaration of protected areas, the law enforcement operations, and embargos on the blacklisted districts and farms. Meanwhile, in the area of food regulation, multiple policy instruments are applied such as the implementation of the persuasive approach, coercive approach, and a combination of persuasive-coercive approach as reported by a broad array of regulatees (Mascini, 2009). Additionally, Lockie (2013) described that regulation which is utilized with the dimension of responsive regulation will be more flexible, efficient, and practical in its approach. Braithwaite (2011) in his study even found that developing countries with limited capacity also experienced positive impact through responsive regulation in which a combination of approach and strategy is utilized.

Regulatory regimes and structure differ across countries. However, most of the hierarchy of regulatory enforcement by governments are presented with a top-down pattern of human interaction which builds upon the ‘command and control’ mechanism against the citizens (Sanders et al., 2014). In relation to regulatory enforcement framework and systems of medicine, these are mainly established by the agency to protect public interest, particularly for quality, safety, and efficacy of medicines. While medicine governance is integral to health, economic, and socio-political sustainability, its management is complex and requires coordination across a range of professional bodies and relevant stakeholders where the interest is primarily to safeguard the public. Ultimately, in the responsive regulation theory, there is implementation of a combination of approaches that ranges from ‘self-regulation’ at the bottom of the pyramid to ‘command and control’ regulation at the top (Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992).

In Malaysia, the regulatory enforcement is mainly characterised by the top-down approach (Nurhisham, 2011; Hasmah, 2009). As a result, the actual number of criminals and the reasons for these criminal problems still remain unsolved. The outcome of the top-down approach powerfully illustrates many loopholes and unfinished jobs, such as new criminals and recidivism. Hence, before proceeding with regulatory improvements and looking at the legal framework, the people need to understand the current regulatory regime and governance of medicine in the country. The aim of this study was therefore to identify the current regulatory regime of medicine regulatory enforcement in Malaysia and analytically investigate it through the perspective of responsive regulation theory.

METHOD

Methodology/Materials

This research employed a qualitative method that focused on documentary evidence and thematic analysis in which low level analysis involving narrative materials of regulatory enforcement of medicine was included (Vaismoradi, Turunen & Bondas, 2013). Through the library search conducted, data were gathered from the statutory laws or regulations related to medicine, statistical books, and annual reports produced by agencies that were published in official government websites. The documents were then analysed thematically according to the identified themes based on the regulatory regime of the agencies. Next, the regulatory structure was identified through the Acts and official organisational chart. The relevant authorities were mapped and presented to provide better understanding of the context. Additionally, other relevant materials were also included such as books and published journals in order to support the analysis and the discussion on responsive regulation theory. All the information was gathered to support and expand the researcher's knowledge to better and further understand the issue under study with the hope of improving the existing law and regulatory structure in the country.

FINDINGS

Regulatory Regime and Structure

In Malaysia, the regulators of the regulatory framework for medicine are all under the purview of the government through the Ministry of Health (MOH) that acts as the federal government regulator groups (Malaysia Productivity Corporation, 2013). The regulatory regime in Malaysia is a public regulatory regime and it is prone to be of the top-down approach. The MOH is a government agency which began with Hospital Taiping in 1880 and since 1957, it has expanded exceptionally until the present day (Ministry of Health, 2021). In line with the rapid growth of the health and pharmaceutical services in the country, pharmaceutical services were established in 1951 with the existence of the Registration of Pharmacists Act 1951 [Act 371], which was then followed by the setting up of the Government Pharmaceutical Laboratories and Stores (GPLS) Complex in 1964. Presently, the Pharmaceutical Services Program (PSP) which was officially established in 1974 acts as the principal regulator in the regulatory enforcement of medicine so that a more comprehensive pharmaceutical service could be delivered to the people (Ministry of Health, 2021). Laws related to medicine have been executed by the divisions and departments under the MOH. The regulatory enforcements are structured according to the power given. In terms of regulatory enforcement power and execution, the departmental agencies involved are the PSP, the National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA), and the Pharmacy Enforcement Division (PED).

The execution of the regulation and legal functions are based on the specific Acts identified below:

1. Registration of the Pharmacist Act 1951 – the authority is given to the Pharmacy Board which is handled by the Malaysia Pharmacy Board under the PSP (Pharmacy Board Malaysia, 2021).

2. Poisons Act 1952 - the authority is given to the Poisons Board which is handled by the PSP and the Licensing Officer (LO) under section 26 of Poisons Act 1952 (Pharmaceutical Services Divisions, 2021).

3. Sales of Drugs Act 1952 - the authority is given to the Drug Control Authority (DCA) and the Director of Pharmaceutical Services (DPS) which are handled by the NPRA (National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency, 2021).

4. Medicine (Advertisement and Sales) Act 1956 - the authority is given to the Medicine Advertisement Board (MAB) which is handled by the PSP (Nik-Rosnah, 2002; Pharmaceutical Services Divisions, 2021).

5. Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 - the authority is given to the Director-General of Health (DG) or the Minister in the MOH which is handled by the PSP (Pharmaceutical Services Divisions, 2021).

All the authorities mentioned above are the so-called 'core regulatory bodies' (Bartle & Vass, 2003). According to the main functions, the five regulatory structures of authority are under the MOH's responsibility and are funded by the government. The power to make regulations and give approvals is subject to the Minister of Health who administers ministerial functions through the Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH). The monitoring of compliances and regulatory enforcements are under the NPRA, PED, and in some situations, it also involves the Royal Malaysian Police and the Royal Malaysian Customs Department.

The function and membership of the core regulatory bodies of medicine in Malaysia are explained below:

1. Pharmacy Board

The Pharmacy Board was established under the Registration of Pharmacists Act 1951 whose function is to regulate the code of conduct and set of procedures for registration and practice for pharmacists. The secretariat of Pharmacy Board, PSP under the MOH is the government department that executes the registration for pharmacists in Malaysia. There are 18 representatives in the Pharmacy Board consisting of stakeholders of the pharmacy profession and pharmacy organisation, including ten members under the public pharmacists, three academic pharmacists, and five private pharmacists. Nonetheless, the representations of professional bodies and advocacy groups or representatives of other stakeholders are still insufficient and lacking. Moreover, there are no representatives from the general public or the users in the Pharmacy Board.

2. Poisons Board

The PSP is the executive government department that assists the Poisons Board. The Poisons Board was established under the provisions of Section 3 of the Poisons Act 1952. It serves to advise the Minister of Health for classification of new chemicals as poison, the amendment of the classification of poison in the Poison List, removal of poison from the Poison List, the amendment of the list of psychotropic substances in the Third Schedule and the addition or deletion of article or preparation in the Second Schedule (Pharmaceutical Services Divisions, 2017). The Poisons Board consists of 13 members. The membership is established under Section 3 of the Poisons Act 1952 and the chairman of the Board is the Director General (DG) of Health. The composition of the members of the Poisons Board is based on the expertise and knowledge of the representatives who are chosen from among those who are able to drive and assist in the decision-making of poison matters, especially in its classification and deletion. Out of the thirteen members of PB, five members are from public services while the other eight members represent the professional bodies and advocacy groups based on the specific fields. Although there is representation of professional bodies in PB, there is not enough members representing the advocacy groups or other stakeholders. In addition, there are no representatives of the general public who are either patients or the users in the PB.

3. Medicine Advertisement Board (MAB)

The secretariat of the Medicine Advertisements Board (MAB) is handled by the PED under the executive body of the Pharmaceutical Services Division (PSD). The Board was established to discuss the approval for application of advertisements of medical products or healthcare facilities and services received. The Board may at its discretion, issue an approval for an advertisement, review, revise its policies and guidelines as necessary and cancel/withdraw the approval granted. As established under Regulation 2 of Medicine Advertisements Board Regulations 1976 and powers conferred by Section 7 of Medicine (Advertisement and Sale) Act 1956, the MAB consists of 15 members, and the chairman of the Board is the DG of Health. Out of the 15 members, four members are private doctors while two are private pharmacists. In MAB membership, however, there are no representatives from private advertising agencies. The composition of the Board members comprises officers in public services and representatives from three groups of professional bodies. However, the representation of professional bodies and advocacy groups or representatives of other stakeholders are still insufficient. Moreover, there is no representation of the general public or the users in the MAB.

4. Drug Control Authority (DCA) under the National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Authority (NPRA)

The Drug Control Authority (DCA) is the executive body established under the Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984 with the National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Authority (NPRA) serving as its Secretariat. The main task of this Authority is to ensure the safety, quality, and efficacy of pharmaceutical, health, and personal care products that are marketed in Malaysia. This objective is achieved through the following:

• Registration of pharmaceutical products and cosmetics

• Licensing of premises for importer, manufacturer, and wholesaler

• Monitoring of the quality of registered products in the market

• Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring

The Drug Control Authority consists of 11 members. DCA’s membership is established under Regulation 3 of the Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984 with powers conferred by Section 28 (1) of the Sale of Food and Drugs Ordinance 1952. The chairman of the Authority is the DG of Health. By law, the composition of the DCA membership comprises 11 members with 11 stakeholders from the physician profession, including seven members representing the public services. However, there is no representation of professional bodies and advocacy groups or representatives of other stakeholders in DCA’s membership. Neither is there a representation of the general public or the users. The number of DCA members might not be enough to oversee the real issues particularly those concerning product tracing and labelling issues.

5. Pharmacy Enforcement Division (PED)

The Pharmacy Enforcement Division (PED) is a government department under MOH. Currently, the officers in PED are appointed as public servants and given power of enforcement under five Acts, namely the Poisons Act 1952 (PA) and its Regulations, Sales of Drugs Act 1952 and its Regulations (SODA), Medicines (Advertisement and Sales) Act 1956 and its Regulations (MASA), Registration of the Pharmacist Act 1951 and its Regulations (ROPA), and Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 and its Regulations (DDA). However, the Dangerous Drugs Act and its Regulations (DDA) are enforced by the Royal Malaysian Police except for the part related to permits which is administered by the PED.

Medicine Regulatees

In regulatory enforcement, the regulators are the ones responsible for regulating the regulatees. Regulatees are a group of stakeholders to the regulators who have to comply with the laws enforced and are also a group of people (industry) that is given focus in the National Regulatory Policy. The definition of stakeholders in this context includes the business community, employees, interest groups, professional organisations, and individuals under the regulatory regime and review such as consumer groups (Malaysia Productivity Corporation, 2013).

To overcome the regulatory problem of medicines in Malaysia, efforts have concentrated on medicine regulation and on planning effective enforcement strategies in controlling the selling or supplying behaviour of the traders, practitioners, and professionals to ensure the sustainability of the prevention action for crime control and medicine safety. Similar to other countries, Malaysia also needs to review and improve its medicine regulatory framework.

The development of globalization has shown the role of the market or the private parties in the formulation of laws and its enforcement which is becoming a challenge to the dominance of strategies of regulatory enforcement in regulating pharmaceutical practitioners and traders. Through the conventional regulatory method of governance, private individuals and businesses lose their freedom and autonomy to bureaucracy and laws. This situation has gradually resulted in the emergence of business entities that act and have a role particularly in areas where the law and economy are controlled by the government. For this reason, the advances in rule-making and enforcement have been identified as one of the proven approaches in regulatory enforcement of medicine in this new era.

In Malaysia, the regulatory enforcement of medicine involves dealing with the professional practitioners, traders, and the traditional practitioners.

1. Professional practitioners

Under the existing medicine Acts and regulations, the professional practitioners are licensed registered pharmacists, registered medical practitioners, registered dentists, and registered veterinarians. There are four groups of interest group under the professional body which can legally sell and supply medicines to their patients and they are:

i. medical practitioners

ii. dentists

iii. veterinarians

iv. pharmacists

The classification of medicine is provided in groups A, B, C, D, and F under Section 20 to Section 25 of the PA. Group B concerns prescription medicine which can only be supplied after receiving a valid prescription from a medical practitioner. Only a qualified person can supply controlled medicine and even a clinic or pharmacy assistant is not allowed to do so without immediate supervision.

2. Traders

In Malaysia, traders who deal with registered medicine products have to obtain a licence before manufacturing, importing, wholesaling, retailing, or using them. The licence is granted by the Director of the Pharmaceutical Services (DSP) for registered medicine. In addition, if the seller deals with scheduled poison, the licence for the related purpose is granted by a licensing officer under Section 27 of the PA.

a) Manufacturers

In Malaysia, under Regulation 12 of the CDCR, the manufacturing of registered medicine products requires a manufacturer’s licence which is issued by the DPS. The licence issued by the DPS includes a processing fee of RM1000.00 as stated under Regulation 13 of the CDCR.

b) Wholesalers

Under regulation 12(1)(b) of the CDCR, all wholesale selling of registered medicine products in Malaysia requires a wholesaler’s licence. The licence is issued by the DPS. The processing fee stated under Regulation 13 of the CDCR is RM500.00. Apart from that, under regulation 7(2)(b) of the CDCR, the importation of medicines to be assembled, enclosed, packed, or re-labelled for re-exporting purposes needs to obtain written approval from the DPS.

c) Importers

The importation of registered medicine products requires an import licence under Regulation 12(1)(d) of the CDCR. The licence is issued by the DPS, and the processing fee stated under Regulation 13 of the CDCR is RM500.00.

d) Retailers

In terms of poison, a retailer who is not a professional practitioner is only allowed to sell Group D poison other than dispensed medicines. For this purpose, the retailer needs to apply for a licence from the Licencing Officer before selling as stated under Section 27 of the PA. However, most of the articles mentioned that the attitudes and perceptions of doctors, manufacturers, and retailers have contributed to the manufacturing and selling of unregistered drugs (Nur-Wahida et al., 2016; Farah-Naz & Aliza, 2016). Such attitudes are considered irresponsible because their concern is only about making profits without feeling any sense of guilt when selling these products which are harmful to the public.

Additionally, a person is eligible of holding only one licence for each type of licence. Thus, if a person already has a Type A licence at one premise, that person is not entitled to hold or apply for any Type A licence at any other premises unless the previous licence has been cancelled. This restriction is imposed to ensure that every premise has only one specific person dealing with the poisons.

For psychotropic substance, the restriction in terms of book recording was expanded in Malaysia when the trend of abuse started to show up here. In the record book, detailed information such as the identification number of the patient (buyer) and the balance of the stock available is required. By imposing this obligation, it restricts the supply of those poisons since every single sale or supply has to be substantiated by the lawful buyer. Even if attempts were made at manipulating the supply with bogus buyers, the truth would be revealed during the audit. These supply audits are performed from time to time by the enforcement agencies.

In terms of registered medicine products other than poison, the retailer is only allowed to sell registered products under Regulation 7(1) (a) of the CDCR. Nevertheless, no retail licence is needed for the retailer to sell registered products other than poison.

3. Traditional Practitioners

In general, traditional medicine practitioners can be divided into three, namely Malay, Chinese, and Indian medicine practitioners. Recently, under the Traditional and Complementary Act 2016, all traditional practitioners are obliged to register with the Traditional and Complimentary Council. The establishment of the Act for traditional practitioners is to ensure that the objective of public safety can be achieved. Nevertheless, the control of medicinal products is still under the Sale of Drugs Act 1952 and Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984. The Traditional and Complementary Medicine Division (T&CM) focuses on regulating and monitoring the practice of traditional or Chinese medicine practitioners. At the same time, the NPRA together with the PED regulate, monitor, and enforce the control of traditional medicinal products.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study found that authorities or regulators of regulatory enforcement of medicine are placed under government agencies (Federal government). The regulation is dominantly designed by the government and is called a command-and-control regulation. This kind of regulation is usually prone to the utilisation of the policing methods in its regulatory enforcement approach to safeguard public interest (Garuba, Kohler & Huisman, 2009; Yapp & Fairman, 2005). The regulatory enforcement of medicine in Malaysia is a public regime.

The regulatory goal of the public regime has no other objectives other than to safeguard public interest where the emphasis is on the importance of social responsibilities. However, most of the regulatees that deal with selling and supplying of medicine are professional practitioners that include registered pharmacists, registered medical practitioners, registered dentists, and registered veterinarians. Additionally, there are also another two categories of regulatees, namely traders and traditional medicine practitioners. Interestingly, almost all the regulatees are private parties. On the other hand, the authorities’ membership included almost no representation of advocacy groups or representatives of other stakeholders. Neither is there a representation of the general public or the users.

The PED regulation setting might be lacking in terms of regulatee contribution and input. Previous studies have found that generally, the regulators and regulatees have different views and conducts or practices of the regulatory approach (Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992). Based on the criticisms and the different political ideologies between the regulators and regulatees, the public regime will lead to contestation and legal issues (Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992). Moreover, the public regime has been criticised as ineffective and expensive, bringing about problems with enforcement, and it aims too much toward the end of pipe solutions (Heijden, 2009).

In conclusion, the current regulatory regime of medicine in Malaysia is of the public regulatory enforcement. This regulatory structure is inadequate as the composition of authorities is prone to represent public services. It significantly leads to inadequate representation and regulatee compliance. This identification of regulatory enforcement of medicine particularly in relation to the regulatory regime in Malaysia would help academics and students in carrying out further research. Concerning the composition of decision-making, this study may help with precise development of a better management system and framing of the regulatory regime through the conduct of further study in the form of interview research. It is suggested that future research assess the regulatory enforcement of medicine in Malaysia through the perspectives of the regulatees and users.

References

- Ayres, I., & Braithwaite, J. (1992). Responsive regulation-transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford University Press.

- Bartle, I., & Vass, P. (2003). Self-Regulation and the regulatory state: A survey of policy and practice. University of Bath Research Report 17.

- Borner, J., Kis-Katos, K., Hargrave, J., & König, K. (2015). Post-crackdown effectiveness of field-based forest law enforcement in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Medicine, 10, 4.

- Braithwaite, J. (2011). The essence of responsive regulation. UBC Law Review, 44, 3, 475-520.

- Castro, D. (2011). Benefits and limitations of industry self-regulation for online behavioral advertising. The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

- Farah Naz Karim & Aliza Shah. (2016). Shameful: Doctors working with cosmetic sellers to inject beauty products. New Straits Times.

- Garuba, H.A., Kohler, J.C., & Anna, M.H. (2009). Transparency in Nigeria's public pharmaceutical sector: Perceptions from policy makers. Globalization and Health, 5(1), 1-14.

- Hasmah, Z. (2009). Regulator and enforcement: A case study on Malaysian communication and multimedia commission. Malaysian Journal of Media Studies, 11, 1, 59-72.

- Heijden, J.V.D. (2009). Building regulatory enforcement regimes: Comparative analysis of private sector involvement in the enforcement of public building regulations. IO Press B.V.

- Lockie, S., McNaughton, A., Lyndal-Joy, T., & Rebeka, T. (2013). Private food standards as responsive regulation: The role of National legislation in the implementation and evolution of GLOBALG.A.P. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 20, 2, 275-291.

- Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC). (2013). National policy on the development and implementation of regulations.

- Mascini, P. (2009). Responsive regulation at the Dutch Food and consumer product safety authority: An empirical assessment of assumptions underlying the theory. Regulation & Governance, 3, 27-47.

- McKay, S. (2003). In pursuit of effective enforcement. The Town Planning Review, 74, 4, 423-443.

- Ministry of Health (MOH). MOH History. National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA), Ministry of Health. Drug Control Authority.

- National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA), Ministry of Health. Obligation of National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency.

- Abdullah, N. (2002). Medical regulation in Malaysia: Towards an effective regulatory regime. Policy and Society, 21(1).

- Nur-Wahida, Z. (2016). The unregistered drugs coverage in the media in Malaysia: Content analysis of the public newspapers. Research in Pharmacy and Health Sciences, 2(3),196-200.

- Hussein, N. (2011). Malaysia’s Economic Transformation. East Asia Forum.

- Pedersen, O.W. (2013). Environmental enforcement undertakings and possible implications: Responsive, smarter or rent seeking? The Modern Law Review.

- Pharmaceutical Services Divisions, Ministry of Health. Pharmacy Enforcement Division.

- Pharmaceutical Services Divisions, Ministry of Health. Pharmacy Practice & Development.

- Pharmaceutical Services Divisions, Ministry of Health. Poisons Board.

- Pharmacy Board Malaysia, Ministry of Health. Membership of Pharmacy Board.

- Sanders, M., Michiel, A.H., & Johan, W. (2014). Energy policy by beauty contests: The legitimacy of interactive sustainability policies at regional levels of the regulatory state. Energy, Sustainability and Society 2014, 4(4).

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405.

- Yapp, C., & Fairman, R. (2005). Businesses?: The impact of enforcement. Law and Policy, 27.