Research Article: 2019 Vol: 18 Issue: 5

Rethinking Scenario Planning Potential Role in Strategy Making and Innovation: A Conceptual Framework Based on Examining Trends towards Scenarios and Firms Strategy

Issam Aldabbagh, Al-Ahliyya Amman University

Sulieman Allawzi, Al-Ahliyya Amman University

Abstract

Purpose: This paper aims to stimulate rethinking expanding scenario planning contribution role in firms strategy making and innovation, while firms management is operating in the middle of global driven markets facing environmental rapid changes and greater uncertainties of the 21st century.

Design: This study is designed to answer a main question; Can examining literatures trends towards scenario planning justifies rethinking expanding horizons of its potential contribution role in strategy making and innovation? The methodology path of this paper passes through three steps: The first consists examining trends through an intentional sample by theme, of 59 literatures published between the period of 1985-2018. The second step consists sketching a big picture based on findings of examined trends. The third step consists of designing studys conceptual framework.

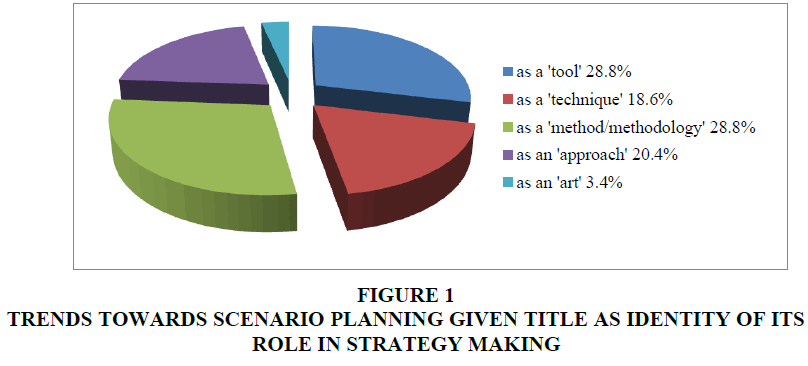

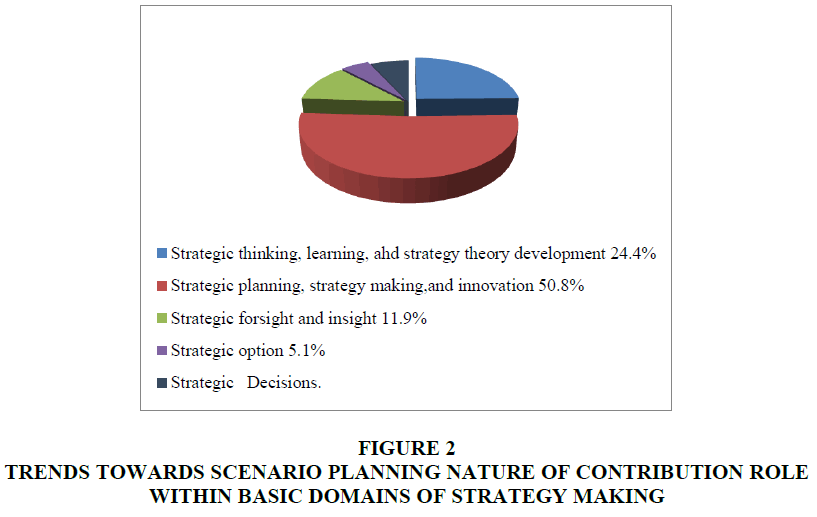

Findings: Examining trends towards scenarios reveals a clear differences between authors trends concerns the given title as identity of scenarios role in strategy making, distributed within five groups scenarios as: tool, approach, technique, method, and as an art. Trends towards the nature of scenarios contribution role were divided between five areas of focus within basic domains of strategy making and innovation: Strategic thinking, learning, and strategy theory development, strategic planning, strategy making, and innovation, strategic foresight and insight, strategic options, and strategic decisions.

Originality/Value: This paper can be considered as novel attempt that provides a conceptual framework based upon findings of examining trends towards scenario planning. This conceptual framework is designed to serve dual causes, to stimulate as well as being a supportive element for; practitioners, researchers, and experts in the field.

Keywords

Scenario Planning, Trends, Strategy Making, Innovation.

JEL Classifications

M1, M10, M19/Strategic Management.

Introduction

The world we live in is in middle of a substantial transforming. 21st century’s challenges are embracing all aspects of our life; social, technologic, economic, politic, and ecologic including earth climate change. What is unusual is not the evolution process by itself; but the high rapidity rate of changes accompanying.

As an active player in this massive rapid change, business firm management’s burden is becoming greater, seeking sustainable means to survive and compete effectively. While business firm is operating in wide global driven markets; environmental variables are characterized by more uncertainty, higher volatility, higher complexity, and higher ambiguity.

One of the main issues preoccupying strategic management’s body of thought, regardless differences in perspectives and approaches between strategic management schools, remains the strategy making and innovation.

Murray (2010) illustrated now day’s difficulties facing corporation’s state while operating in the middle of new market forces changes when he wrote, in today’s world, gale-like market-forces-rapid globalization, accelerating innovation, relentless competition-have intensified what can be called, the forces of “creative destruction”. Decades-old institutions like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns now can disappear overnight, while new ones like Google and Tweeter can spring from nowhere. Even the best-managed companies are not protected from this destruction clash between whirlwind change and corporation inertia (Murray, 2010).

Appeals for innovation, or even reinventing management, as the strategy consultant Gary Hamel’s, seeking innovative ideas for handling modern management challenges; As Grant (2008) alludes, haven’t succeeded in answering the question “What will be the replacement for the corporation look like?”. This perhaps the raison that drove Grant (2008) gives his criticism about Hamel’s book The Future of Management; for Grant, Hamel himself admits that

“The thing that limit us, is that we are extraordinarily familiar with the old model, but the new model, we haven’t even seen yet”.

This perhaps also explains also, why Murray (2010) has considered management innovation and reinvention appeal, as to be the core of “innovator’s dilemma”. In his article “The End of Management” 2010, perhaps goes a little bit too far in pessimism, when he concluded wandering whether the 20th century corporation evolve into new, 21st century organization? It will not be easy. “The old methods won’t last much longer” Murray (2010).

Grant (2008) argued about Gray Hamel’s innovation appeal, that “It is surely right”, admitting that

“Changes in the business environment and new technologies will drive for-reaching changes in structures, systems and leadership styles”.

What is not evident for Grant (2008) is that

“These adaptations require a new management paradigm. Nor it is obvious that 21st century management will be based upon distributed innovation, participative decision making and market-based mechanisms, as Hamel’s appeal reclaimed”.

He also recognized that these changes imply different leadership styles and approaches to decision making, “but not the wholesale dismantling of existing management practices or principle that underpin them” Grant (2008).

In response to different views of authors, researchers, and business practitioners about future management and innovation appeals; we believe that management field in general, and strategic management discipline in particular, is still young, dynamic, and evolving. Thus, we must admit the fact that innovation and probably even reinventing, remains needed by nature of evolving. In addition, this applies as well in any of the scientific knowledge fields. However, in today’s business world, phenomenon as the failure of certain number of businesses including some giant corporations could have a multi probable causes located between miss adaptations to environmental rapid changes, and inadequate strategic combination. Yet, within such wide margin of probable raisons that can contribute in explaining firm’s failure, questioning management’s paradigms, principles, and outstanding practices, cannot be at the top of such list. Otherwise, it becomes an unfair judgment, while clear alternative modern management model is still absent and yet unseen as some innovationist’s advocates as Gray Hamel admitted himself.

Environmental rapid changes and accelerating evolutions in different aspect of our world, made the “forecasting” traditional method widely used before in strategic planning and strategy making, loses its golden age. Wack’s (1985) article Scenarios: Uncharted Waters A head, published in 1985 at Harvard Business Review, argued that it is fashionable to downplay and even denigrate the usefulness of economic forecasting. The reason is obvious, forecasters seem to be more often wrong than right.

For Wack (1985), the weakness of “forecasts” came from their basic point of go, they are usually constructed on the assumption that tomorrow’s world will be much like today’s they say, often work because the world does not always change. However, say, eventually forecasts will fail when they are needed most: in anticipation major shifts in business environment that make whole strategies obsoletes, Wack (1985). Ever since, “Scenario Planning” as a term became widely used specially by authors, researchers, and practitioners within strategic management and business field.

This study, suggests that rethinking “scenario planning”, becomes highly important not only because it represent a research emerging gap in form of seeking a conceptual framework allowing a clear methodology for expanding scenario planning contribution, but also because scenarios represents a scientific alternative while traditional forecasting is in its decline stage. Thus scenarios as one of the most dynamic strategic management’s practices for its higher potential role in dealing with futures rapid changes and uncertainties that can accompany as well. Reviewing literatures trends about its contribution role in different strategy making/formation basic domains, could provide fresh ideas and open new horizons about scenario planning potential contribution role, and perhaps will open some new horizons towards firm’s strategy combination innovation to cope with 21st century’s challenges. In fact, Scenario planning could be considered as one of the strategy higher dynamic practices for its role in dealing with futures and uncertainties. Through firm’s strategy formation, regarding its advantages and limitations; represents high potentialities.

The methodology of this study consists examining trends through an intentional/ purposed sample “by theme”, of 59 literatures (articles and book’s chapters) published during more than 33 years, between 1985 and 2018, in the field, studying the nature of their focus and consensus, determining their views distribution about scenario planning contribution role in firm’s strategy and innovation. Results of examining trends toward scenarios and strategy making can allow sketching the big picture and makes possible to design this study’s proposed conceptual framework for rethinking expanding scenarios role in firm’s strategy making and innovation.

Strategy Making the Core Issue for Dominate Schools of Thought on Strategy

The reason why firms succeed or fail is perhaps the central question in strategy. It has preoccupied the strategy field since its inception. Almost three decades after Porter’s (1991) statement, an extraordinary progress that has been achieved in the field. The large part of the credit goes back to pioneers and milestones among those, Michael Porter himself.

As Mintzberg et al. 1998, suggested, the theory and practice in strategic management observe three main perspectives (or streams) entailing ten different schools of thought. The three streams are the “Prescriptive perspective, the describing perspective, and the configuration perspective”. Each stream entails a number of schools of thought. The prescriptive perspective focuses on the show of strategies formulation. Instead, the describing perspective focuses on illustrating (or describing) how is that strategies are made. Finally, the configuration perspective focuses on synthesizing and integrating of the previous views.

Adopting Mintzberg’s 1990 &1998 taxonomy, all dominant schools of thought within strategic management discipline; they are by historical order: Design school, planning school, positioning school, entrepreneurial school, cognitive school, teaching school, power school, cultural school, environmental school, and the configuration school (see Table 1).

| Table 1 Mintzberg’s Taxonomy of Strategic Management Dominant Schools of Thought | |

| Perspective | School |

| Prescriptive | Design School |

| Planning School | |

| Positioning School | |

| Describing | Entrepreneurial School |

| Cognitive School | |

| Learning School | |

| Power School | |

| Cultural School | |

| Environmental School | |

| Configuration | Configuration School |

Reviewing Mintzberg (1990 &1998); Porter (1991); Brews & Hunt (1999); Elfring & Valberda (2001); Cairns et al. (2006); Whittington & Cailluet (2008); Jofer (2011); Tappin (2012); Planellas (2013); Geisler & Christian (2013); Guerras-Martin et al. (2014); Hattangadi (2017); Proved how and why, strategy making/forming, remains a core issue of strategic management field. The ten dominant schools of thought on strategy; whatever is the chosen perspective or prescriptive stream taken by these dominant schools of thought, their core issue remains about strategy making/formation. Special emphasis on improving attempts to figure out a proper strategic combination that allows the firm’s management to move from one position to another, enlarging horizons and opportunities in front of business firm to survive and compete through an innovative strategic behavior.

Scenarios and Scenario Planning

Foresight is about establishing a vision/sight of the future. Foresight goes in pair with future studies, and is closely associated with scenario building. Foresight can be defined “as a systematic, participatory, future intelligence-gathering and medium-to-long vision-building process aimed to present day decisions and mobilizing joint action” IPTS (2003).

Most of the roots of the field foresight can be found in the USA, where the application of foresight techniques in the defense industry and thereafter in the “Energy Industry”, took off in the 50-60’s. Among the pioneers of foresight, one fined the RAND Corporation and the Hudson Institute (founded by H. Kahn). Over the years, governments and corporations started to conduct foresight studies in order to better plan technology-related investments. The field of foresight has developed in parallel with the growing awareness of the need for future orientation and recognition of uncertainties about the future, both at corporate and governmental level, Rialland & Wold (2009).

The fundamental of a future scenario is that it aims at treating uncertainty. Scenarios are “structurally different stories about how future might develop”, that are believed to have an impact on the field on focus (Kroneberg et al., 2001).

Strategic planning and futures studies are converging through joint application in practice and their literatures. The strategic planning model provided a kind of structure designed for integrating and organizing the many methods and techniques that are used by futurists. Thus, futures studies and strategic planning are indeed highly complementary.

Scenario building and planning was further developed for management purposes, for example through the works of Peter Schwartz and colleagues from the GBN-Global Business Network (2008), Inayatullah Sohail (2008), or other authors like Heijden, van der (2008); Ringland (1998); Mietzner & Reger (2004) mainly with a background from companies.

Schoemaker (1995) argued that Mintzberg 1994’s alludes to in his pivotal work decrying the pervasiveness of disjointed planners in modern organizations. Strategic planning, as it has been practiced, has really been “strategic programming”, planning has always been about analyses about breaking down a goal or set of intentions into steps, formulizing those steps so that they can be implemented almost automatically and articulating the anticipated consequence or results of each step. Schoemaker (1995) wrote that in fact, Mintzberg in 1994 argued also that strategic thinking is about synthesis, it involves intuition and creativity, and that the outcome of strategic thinking is an integrated perspective of the enterprise, a not-too-precisely articulated vision of direction. Scenarios can build a shared framework for “strategic Thinking” that encourages diversity and sharper perceptions about external changes and opportunities, Schoemaker (1995).

Conway (2004) in her article “Scenario Planning: An Innovative Approach to Strategy Development”, wrote that there is now some recognition that this missing element is the capacity to develop and maintain a systematic view of the future-a foresight capacity. Scenario planning is a futures methodology now widely used by organizations and governments to incorporate such a futures view into planning. While using scenario planning will introduce organizations to the value of exploring the future, selection of a methodology is only one part of the integration of a more comprehensive futures approach into strategy formation, decision making and implementation-that is, to develop and sustain an organizational capacity for foresight. Integrating a futures approach into traditional strategic planning models in order to develop a foresight capacity requires not only an understanding of what a futures approach is-as opposed to only using a methodology like scenario planning-but also a fundamental reconceptualization of the strategic planning model itself (Conway, 2004; Perry, 1996).

Seeking more objectivity to this study’s proposal of rethinking expanding scenario planning contribution role in strategy making and innovation, we believe that it’s vital to highlight scenarios advantages as well as their limits and weaknesses.

Scenario Planning Advantages and Limitations

Scenario planning main advantages

Opinions and views about advantages of scenario planning in this paper were studied from the angle of their potential contributions in organization’s strategy making was argued by; Wack (1985); Fink & Schlake 2000); Van der Heijden (2011); Ratcliffe (2002); Schoemaker (1995); Rialland & Wold (2009); Edgar et al. (2010); Wulf et al (2010); Burt et al. (2006); Drew (2006); GNB Global Business Network (2008); Conway (2004); Wilburn & Wilburn (2011); Ram et al (2011); De Smedt et al (2012); Mietzner & Reger (2004); Geissler & Krys (2013); Schwenker & Wulf (2013); Fähling et al. (2012). These main advantages could be summarized to serve this study’s purposes:

• Scenarios do not describe one future, but several realizable or desirable futures to be imagined. Thus, scenarios open up the mind, stimulating strategic thinking and strategic foresight through indicating unimaginable possibilities, challenge long-held internal beliefs of an organization; they can change the corporate culture, compelling its managers to rethink radically the hypotheses on which they have ground their strategy.

• Scenarios are appropriate means to better understand even “Weak signals” of the technological discontinuities, disruptive events of the environment allowing organization to be well prepared to handle new situations as they arise by promoting proactive leadership initiatives and innovations to take place. Future scenarios can be used as a mean for orienting innovation systems. Cooperative strategies participatory scenario analysis can produce a variety of possible and not only probable or desired futures diffuse and use innovations. Thus, scenarios can be used as a kind of toolbox or framework for innovation managers.

• Scenario planning as an introduction approach of new innovations as well as a powerful tool to use when there is high uncertainty level in the strategy making process. Scenarios can lead the creation of common language for dealing with strategic issues through opening a strategic conversation within an organization’s difference levels involved in strategy making process. During the scenario process; aims, opportunities, risks and strategies are shared in a cooperative manner between participants. Organizational learning, decision-making process can improve. Scenario building processes are flexible and able to be adjusted to the specific task/situation. “Strategic options” against the multiple scenarios makes company’s strategy more robust and applicable in several possible future situations. This advantage enables leaders/strategists to act more flexibly and be prepared for different strategic alternatives depending on how futures turn out to be.

Scenarios main limits and weakness

In spite of scenario planning’s multi dimensions advantages, it forms a subject of criticism in many occasions for its limits and weaknesses:

• Schoemaker (1995), in his article “Scenarios planning: A tool for strategic thinking”; concluded that, although scenarios can free our thinking they can still be affected by biases. When we are making predictions, we tend to look for confirming evidence and discount disconfirming evidence, and this bias can creep into the scenario development. Moreover, in Schoemaker’s (1995) conclusions, he added that when contemplating the future, it is useful to consider three classes of knowledge: (1. Things we know we know, 2. Things we know we do not know; and 3. Things we do not know we do not know). Various biases -overconfidence -and over - prediction, the tendency to look for confirming evidence -plague all three, but greatest havoc is caused by the third: “Things we don’t know we don’t know”, Schoemaker (1995).

• Michael Porter in his article “Towards a Dynamic Theory of Strategy”, raises broader question “Why firms succeed or fail?” in this article Porter believes that any effort to understand success must rest on an underlying theory of the firm and an associated theory of strategy. For his part of the main question, Porter re-raises a frontier question of “How, then, do we make progress towards a truly dynamic theory of strategy?” In this same article Porter, examined three “promising lines” of enquiry that have been explored: (Game theoretical models -including “scenarios”, Commitment and uncurtaining, and the Resource -based view). Focusing on Porter’s analysis about scenarios potential contribution, Porter in this article admitted that the scenario -approach tends to stress the value of flexibility in dealing with change rather than the capability to rapidly improve and innovate to nullify or overcome it. By focusing on discrete choices, the discretion a firm had to shape its environment, respond to environmental changes, or define entirely new positions in implicitly limited or not operationalized by most treatments (Porter, 1991).

• Mietzner & Reger (2004) in their article “Advantages and disadvantages of scenario approaches for strategic foresight”; they concluded several weaknesses in “scenario techniques”.

• A qualitative approach has to put a strong emphasis on the selection of suitable participants/experts, and in practice, this could not be an easy task to fulfill. Thus, a deep understanding and knowledge of the field under investigation is necessary.

• Data and information from different sources have to be collected and interpreted which makes scenario building even more time. (And resource) -consuming. It could be difficult not to focus on “black” and “white” Scenarios or the most likely scenario (Wishful Thinking) during the scenario building process. Scenarios are often considered as primarily a tool for large and multinational corporations. This fact illustrates their limitations to be widely used in small and medium -sized organizations.

• In his paper for the McKinsey & Company; “The use and abuse of scenarios”, Roxburgh (2009) argued the fact that there is a downside to scenarios. Inexperienced people and organizations are prone to fall into a number of traps.

• Creating a range of scenarios that is appropriately broad, especially in today’s uncertainties, can paralyses leadership. The tendency to think we know what is going to happen is in some ways a survival strategy: it makes us confident in our choices (However misplaced the confidence may be). In the face of a wide range of possible outcomes, there is a risk the organization becomes confused and lacking in direction, and it changes nothing in its behavior:

Using scenario can induce a sense of complacency, they are not so different from the value-at-risk models employed by the financial sector when they provided projections of what would happen 99% of the time. This induced a false sense of security about the potentially catastrophic effects of an event with a 1% probability.

Creating scenarios that do not cover the full range of possibilities can leave you exposed exactly when scenarios provide most contort. Even when constructing scenarios, it is easy to be trapped by the past. Tendency of ordinary people when they are in front of presented range of scenarios; will be to choose one or two immediately to the right and left of reality so they experience it at the time. They regard extreme scenarios as a waste because “They won’t happen”. By ignoring the outer scenarios and spending their energy on moderate improvements or deteriorations from the present, organizations leaves themselves exposed to dramatic changes -particularly on the downside. Strategists must include “stretch” scenarios while acknowledging their low probability. Strategists will not want to use scenarios when uncertainty is so great that they cannot be built reliably at any level of detail. For Just as scenarios help to avoid groupthink, they can also generate a groupthink of their own. If everyone in an organization thinks the world can be categorized into four boxes on a quadrant, it may convince itself that only four outcomes or kinds of outcomes can happen. The future is multivariate, and there are elements that strategists will miss. They should therefore avoid scenarios that fall on a single spectrum (very good, good, not so good, and very bad). At least two variables should be used to construct scenarios and the variables must not be dependent, or in reality, there will be just one spectrum Roxburgh (2009).

Although, comparing scenario planning potentialities with its limitations illustrates some difficulties to be reconsidered about its time consuming and unpopular wide use, the core of these limitations remains not far of being adjustable, nor to decreases from its valuable Potential role in strategy making. Examining Trends towards Scenario Planning Role within Strategy Making:

Conway’s (2004) argued that the relationship between strategy and planning is complex and interdependent. For her, most strategic planning models assume that strategy making is just one-step in a defined and well-understood planning process, which results in the production of written plans that later will be implemented by staff across an organization. The purpose and role of each stage in the overall planning process, particularly the strategy development stage is often not clear. Thus, in this study, focus will be on considering the term strategy making/formation within its research-terminology, as to include the overall of strategy formulation task where formulated or made strategy is the outcome.

Examining Scenario Planning Potential Role in Strategy Making and Innovation

The methodology used in this study consists covering literatures review by using the “Web”, (Internet’s World Wide Web, or Internet-based hypertext system); The attempt was realized through an intentional sample “by theme” of 59 (article and book-chapters) published and defused to be available online between 1985 and 2018. Studying author’s points of view about scenario’s contribution role within strategy making /formation basic components, allows sketching a picture of their trends about the subject in question through two phases : Phase one is “Trends towards scenarios, distribution within by their given “titles” to scenarios, aiming to investigate trends of given “identity” to scenarios role in strategy making”, Phase two is “Trends towards scenarios contribution role distribution, within five basic components of strategy making, aiming to investigate the “nature” of scenarios contribution role in strategy making”.

Finding discussing of phase one: Examining trends towards scenario planning potential role “title”, as given role identity

A clear differences between authors trends concerns the given “title” as identity of scenarios role in strategy making, distributed within five groups scenarios as: tool, approach, technique, method, and as an art. The distribution of trends by their given “title” for scenario planning role in strategy making is shown in both Table 2 and Figure 1.

| Table 2 Trends Distribution by Given Title to Scenario Planning Role Within Strategy Making/Formation | ||||||

| Title | As a Tool | As a Technique | As a Method/Methodology | As an Approach | As an Art | Total |

| Frequency | 17 | 11 | 17 | 12 | 2 | 59 |

| Percentage | 28.8% | 18.6% | 28.8% | 20.4% | 3.4% | 100% |

From Table 2 and Figure 1; Trends towards scenario planning potential contribution role in strategy making/formation distributed by given “title”, examining findings shows that:

1. Scenario planning potential role titled as a “Tool”, representing 17 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published researches (articles and books), with a relative weight of 28.8%. Authors considering scenarios role identity as a tool are Porter (1985); Schoemaker (1995); Mintzberg et al. (1998); Fink & Schlake (2000); Lindgren & Bandhold (2003); Peterson et al. (2003); Edgar et al. (2010); Vann et al. (2012); De Smedt et al. (2012); Amer et al. (2013); McWhorter et al. (2014); Berisha Qehaja et al. (2017); Derbyshire (2018); Inayatullah Sohail (2008); Gavetti & Menon, (2016); Fitzsimmons (2018).

2. Scenario planning potential role titled as a “Technique” representing 11 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published (articles and books), with a relative weight of 18.6%. Authors considering scenarios role identity as a technique are Wack (1985); Porter (1991); Bradfield et al. (2005); Drew (2006), Wilburn &Wilburn (2011); Fähling et al. (2012); Schwenker & Wulf (2013); Lehr et al. (2017); Brummell & McGillivary (2017); Fairholm (2009); GNB (2008).

3. Scenario planning potential role titled as a “Method /Methodology” representing 17 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published (articles and books) with a relative weight of 28.8%. Authors considering scenarios role identity as a “method or methodology” are Ratcliffe (2000); Conway (2004); Stone & Redmer (2006); Cairns et al. (2006); Merwe Louis van der (2008); Rialland & Wold (2009); Gates (2010); Roney & College (2010); Ram et al. (2011); Srinivasan (2012); Avis (2017); Nigatu (2018); IKI-Ivan -klinec-Institue (2011), Best Eric (2018), Peter & Jarrat (2015); Wilkinson & Edinow (2008); ALIS (2013).

4. Scenario Planning potential role titled as an “Approach” representing 12 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published (articles and books), with a relative weight of 20.4%. Authors considering scenarios role identity as an “approach” are Mietzner & Reger (2004); Burt et al. (2006); Chermack (2002); Chermack et al. (2006); Baraev (2009); Wulf et al. (2010); Ramírez & Selin (2014); Geissler & Krys (2013); Moniz (2006); Rohrbeck et al. (2015); Tibbs (1999); O’Shannassy (1999).

5. Scenario planning potential role titled as an “Art” representing 2 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published (articles and books), with a relative weight of 3.4 %. Authors considering scenarios role identity as an “art” are Godet (2000); Heijden (2005).

Finding discussing of phase two: Examining trends towards scenario planning potential role nature

Phase two includes examining trends towards potential contribution role “nature” for scenario planning, distributed within basic domains of strategy making /formation: Trends towards the “Nature” of scenarios contribution role were divided between five areas of focus within basic domains of strategy making and innovation: Strategic thinking, learning, and strategy theory development Strategic planning, strategy making, and innovation, Strategic foresight and insight, Strategic options, and Strategic decisions. The distribution of trends by “nature” of contribution role of scenario planning within basic domains involved in strategy making /formation process and content is shown in Table 3 & Figure 2.

| Table 3 Trends Towards Potential Contribution Role Nature for Scenario Planning, Distributed Within Basic Domains of Strategy Making/Formation | ||||||

| Nature of contribution Focus | Scenario planning given role in Strategic thinking, learning, and strategy theory development. | Scenario planning given role in Strategic Planning, Strategy Making and Innovation. | Scenario planning given role in: Strategic Foresight and Insight. | Scenario planning given role in: Strategic Options. | Scenario planning given role in: Strategic Decisions. | Total |

| Frequency | 15 | 30 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 59 |

| Percentage | 24.4% | 50.8% | 11.9% | 5.1% | 6.8% | 100% |

Figure 2 Trends Towards Scenario Planning Nature of Contribution Role Within Basic Domains of Strategy Making

Table 3 Trends distribution by “nature” of contribution role of scenario planning within basic domains involved in strategy making/formation process and content.

From Table 3 & Figure 2 trends towards scenario planning contribution role of scenario planning, distributed by role nature within basic domains of strategy making /formation, examining results shows that;

1. Nature of scenario planning contribution role in strategic thinking, learning, and strategy theory development representing 15 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published (articles and books), with a relative weight of 25.4%. Authors considering scenarios contribution role “nature” to be within the domain of, Strategic Thinking, Learning, and Strategy Theory Development (Porter, 1991; Schoemaker, 1995; Fairholm, 2009; Heijden, 2005; Vann et al., 2012; IKI-Ivan klinec Institute, 2011; Inayatullah Sohail, 2008; Best Eric, 2018; Srinivasan, 2012; McWhorter et al., 2014; O’Shnnassy, 1999; Lindgren & Bandhold, 2003; Ramírez & Selin, 2014; Moniz, 2006).

2. Nature of scenario planning contribution role in strategic planning, strategy making and innovation representing 30 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published (articles and books), with a relative weight of 50.8%. Authors considering scenarios contribution role “nature” to be within the domain of; Strategic Planning, Strategy Making and innovation (Porter, 1985; Bradfield et al., 2005; Roney & College, 2010; Baraev, 2009; Conway, 2004; Godet, 2000; Stone & Redmer, 2006; Wack, 1985; Ratcliffe, 2000; Drew, 2006; Wulf et al., 2010; Edgar et al., 2010; Schwenker & Wulf 2013; Fähling et al., 2012; Gates, 2010; Tibbs, 1999; Merwe, 2008; Meitzner & Reger, 2004; Avis 2017; Amer et al., 2013; Burt et al., 2006; Lehr et al., 2017; De Smedt et al., 2012; Geissler & Krys, 2013; Mintzberg et al., 1998; Peterson et al., 2003; Berisha Qehaja et al., 2017; Chermack, 2002; Chermack et al., 2006; Derbyshire, 2018).

3. Nature of scenario planning contribution role in (Strategic Foresight and Insight), representing 7 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published (articles and books), with a relative weight of 11.9%. Authors considering scenarios contribution role “nature” to be within the domain of; Strategic Foresight and Insight: (ALIS 2013; Peter & Jarrat, 2015; Fink & Schlake, 2000; Cairns et al., 2006; Wilkinson & Edinow, 2008; Rohrbeck et al., 2015; Fitzsimmons, 2018).

4. Nature of scenario planning contribution role in (Strategic Options), representing 3 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published (articles and books), with a relative weight of 5.1%. Authors considering scenarios contribution role “nature” to be within the domain of; Strategic Options: (GNB 2008; Ram et al., 2011; Gavetti & Menon, 2016).

5. Nature of scenario planning contribution role in strategic decisions representing 4 frequencies within the 59 reviewed published (articles and books), with a relative weight of 6.8%. Authors considering scenarios contribution role “nature” to be within the domain of; Strategic Decisions, (Brummell & McGillivray, 2017; Nigatu, 2018; Wilburn & Wilburn, 2011; Rialland & Wold, 2009).

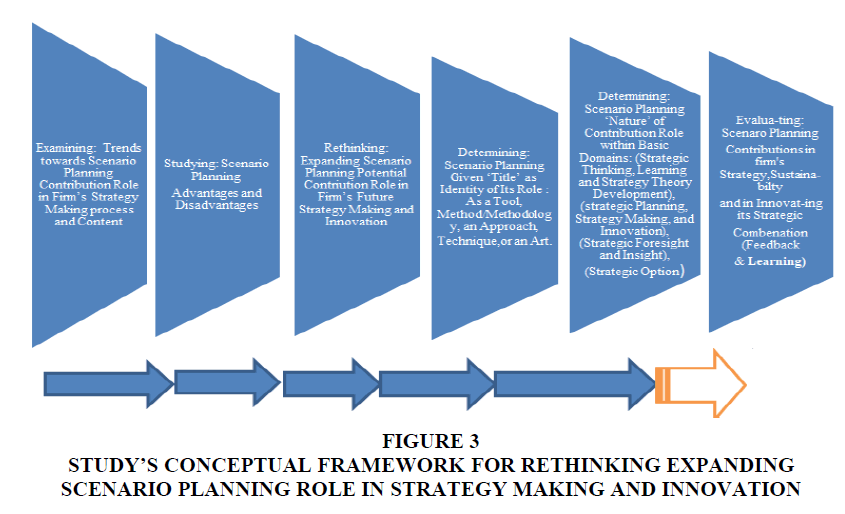

This study, in the light of its examining trends findings shown in Table 2 & Table 3, designed a conceptual framework sketching a methodological path adopting examining trends towards potential role of scenario planning in strategy making/formation process, as a starting point. This starting point will be followed with sketching a clear picture determining two main issues; the “title” given as identification of scenarios role, and the “nature” of contribution in firm’s strategy making. Studying scenarios advantages as well as disadvantages will allow releasing rethinking process. See Figure 3.

Figure 3 Study’s Conceptual Framework for Rethinking Expanding Scenario Planning role in Strategy Making and Innovation

Conclusion

Strategy making/formation remains a core value and a top listed issue of preoccupation for all dominant schools of thought within strategic management discipline, regardless differences of their perspectives between each of them. Ultimately, authors, researchers, experts and practitioners in the world of business are seeking sustainable and strategy combination innovation, to better cope with 21st century’s challenges where rapid changes are becoming greater.

In fact, scenario planning as deeply involved “methodology” in futures and uncertainties was one of the main drivers for this study to adopt its aim of rethinking scenarios potential contribution role in firm’s strategy. For this study, investigating trends through a sample of 59 research-work published during more than 33 years, (1985-2018); reveals that scenario planning do, and can play a considerable role contributing in strategy making process and content. The distribution of trends towards scenarios role can be ranked, by relative importance weight, in five groups of basic domains of strategy: strategic thinking, learning, and strategy theory development, strategic planning, strategy making and innovation, strategic foresight, and insight, strategic decision making and strategic option.

Taking in consideration outcomes of this study’s investigation of scenarios advantages and weakness, results of examining trends towards scenarios allows, by its richness, designing a conceptual framework, the drown picture in this framework can serve for locating areas where scenario planning attracted researcher’s focus the most. Study’s suggestions include for farther research the use of such framework, as a road map, that can be helpful in deciding their priority in choosing future research topics. For practitioners and strategists in business, while they are facing 21st century’s huge challenges and rapid environmental changes, this study suggests also that the developed framework could be useful in selecting in which domain of their firm’s future strategy making, and strategy combination. In fact scenario-planning possibilities and potentialities can better serve; due it has been empirically tested with different degrees of success in large corporations since the “Royal Dutch/Shell” of 1970’s. Finally, for specialists in the theme, it is essential and highly recommended to focus on decreasing scenario planning weaknesses, limits and disadvantages, seeking ways to bring adequate adjustments that can transform “scenario planning” to become more popular, less time and cost consuming, enabling its wider effective use in strategy making process even by small and medium sized organizations.

References

- ALIS-Abrams Learning and Information Systems-2013 (n.d.). Strategic foresight and scenario based planning. Retrieved March 12, 2018 from http://www.alisinc.com

- Amer, M., Daim, T.U., & Jetter, A. (2013). A review of scenario planning. Futures, 46, 23-40.

- Avis, W. (2017). Scenario thinking and usage among development actors.

- Baraev, I. (2009). Future scenario planning in strategic management.

- Berisha Qehaja, A., Kutllovci, E., & Shiroka Pula, J. (2017). Strategic management tools and techniques: A comparative analysis of empirical studies. Croatian Economic Survey, 19(1), 67-99.

- Best Eric (n.d.). An introduction to scenario thinking. Retrieved February 02, 2018 from http:// www.ericbestonline.com

- Bradfield, R., Wright, G., Burt, G., Cairns, G., & Van Der Heijden, K. (2005). The origins and evolution of scenario techniques in long range business planning. Futures, 37(8), 795-812.

- Brews, P.J., & Hunt, M.R. (1999). Learning to plan and planning to learn: Resolving the planning school/learning school debate. Strategic Management Journal, 20(10), 889-913.

- Brummell. A., & Mac Gillivray G. (2017). Introduction to Scenarios: Scenarios to Strategy Inc.

- Burt, G., Wright, G., Bradfield, R., Cairns, G., & Van Der Heijden, K. (2006). The role of scenario planning in exploring the environment in view of the limitations of PEST and its derivatives. International Studies of Management & Organization, 36(3), 50-76.

- Cairns, G., Wright, G., Van der Heijden, K., Bradfield, R., & Burt, G. (2006). Enhancing foresight between multiple agencies: issues in the use of scenario thinking to overcome fragmentation. Futures, 38(8), 1010-1025.

- Chermack, T.J. (2002). The mandate for theory in scenario planning. Futures Research Quarterly, 18(2), 25-28.

- Chermack, T.J., Lynham, S.A., & Van der Merwe, L. (2006). Exploring the relationship between scenario planning and perceptions of learning organization characteristics. Futures, 38(7), 767-777.

- Conway, M. (2004). Scenario planning: an innovative approach to strategy development. Australasian Association for Institutional Research, Sidney.

- De Smedt, P., Borch, K., & Fuller, T. (2013). Future scenarios to inspire innovation. Technological forecasting and Social Change, 80(3), 432-443.

- Derbyshire, J. (2017). Potential surprise theory as a theoretical foundation for scenario planning. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 124, 77-87.

- Drew, S.A. (2006). Building technology foresight: using scenarios to embrace innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 9(3), 241-257.

- Edgar, B., Abouzeedan, A., & Hedner, T. (2010). Scenario planning as a tool to promote innovation in regional development context.

- Elfring, T., & Volberda, H.W. (2001). Theory, schools and practice.

- Fähling, J., Huber, M., Böhm, F., Leimeister, J.M., & Krcmar, H. (2012). Scenario planning for innovation development: an overview of different innovation domains. Int. J. Technology Intelligence and Planning, 8(2), 95-114.

- Fairholm, M.R. (2009). Leadership and Organizational Strategy. Innovation Journal, 14(1).

- Fink, A., & Schlake, O. (2000). Scenario management approach to strategic foresight. Competitive Intelligence Review: Published in Cooperation with the Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals, 11 (1), 37-45.

- Fitzsimmons, M. (2018). Strategic insights: Challenges in using scenario planning for defense strategy.

- Gates, L.P. (2010). Strategic planning with critical success factors and future scenarios: An integrated strategic planning framework.

- Gavetti, G., & Menon, A. (2016). Evolution cum agency: Toward a model of strategic foresight. Strategy Science, 1(3), 207-233.

- GBN-Global Business Network (n.d.). Retrieved February 02, 2018 from at: http://globalnetworkbusiness.com/

- Geissler, C., & Krys, C. (2013). The challenges of strategic management in the twenty-first century. In scenario-based strategic planning. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden.

- Godet, M. (2000). The art of scenarios and strategic planning: tools and pitfalls. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 65(1), 3-22.

- Grant, R.M. (2008). The future of management: Where is Gary Hamel leading us?. Long Range Planning, 41(5), 469-482.

- Guerras-Martin, L.Á., Madhok, A., & Montoro-Sánchez, Á. (2014). The evolution of strategic management research: Recent trends and current directions. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 17(2), 69-76.

- Hamel G. & Breen B. (2007). The future of management. Harvard Business School Press, Boston. http:// www.ericbestonline.com

- IKI-Ivan Klinec Institute (n.d.). Economic Research 2011. The international lower Silesian conference. Retrieved from http://www.narodacek.cz/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Proceedings_2017_Part_I_web.pdf

- Inayatullah, S. (2008). Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming. Foresight, 10(1), 4-21.

- IPTS- Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (n.d.). Retrieved February 02, 2018 from http://www.forlearn.jrc.ec.europa.eu/index.htm

- Jofre, S. (2011). Strategic Management: The theory and practice of strategy in (business) organizations.

- Kroneberg, A., Landmark, T., & Nilsen, R. 2001. Strategy development in international shipping by using scenarios. Marintek publication.

- Krys, C. (2013). Scenario-based strategic planning: Developing strategies in an uncertain world. B. Schwenker, & T. Wulf (Eds.). Wiesbaden: Springer gabler.

- Lehr, T., Lorenz, U., Willert, M., & Rohrbeck, R. (2017). Scenario-based strategizing: Advancing the applicability in strategists' teams. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 124, 214-224.

- Lindgren, M., & Bandhold, H. (2003). Scenario planning. Palgrave.

- McWhorter, R.R., & Lynham, S.A. (2014). An initial conceptualization of virtual scenario planning. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 16(3), 335-355.

- Mietzner, D., & Reger, G. (2004, May). Scenario approaches-history, differences, advantages and disadvantages. In EU-US Seminar: New Technology Foresight, Forecasting and Assessment Methods, Seville, May (pp. 13-14).

- Mintzberg, H. (1990). Strategy formation: Schools of thought. Perspectives on Strategic Management, 1968, 105-235.

- Mintzberg, H. (1994). Rethinking strategic planning part II: new roles for planners. Long Range Planning, 27(3), 22-30.

- Mintzberg, H. (1994). The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harvard business review, 72(1), 107-114.

- Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B., & Lampel, J. (2005). Strategy Safari: a guided tour through the wilds of strategic mangament. Simon and Schuster.

- Moniz, A. B. (2006). Scenario-building methods as a tool for policy analysis. In Innovative Comparative Methods for Policy Analysis (pp. 185-209). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Murray, A. (2010). The end of management. The Wall Street Journal, 21.

- Nigatu B. 2018. Scenario planning versus traditional forecasting. Retrieved February 02, 2018 from https://blog.reckonedforce.com/scenario-planning-versus-traditional-forecasting/

- O'Shannassy, T. (1999). Strategic thinking: a continuum of views and conceptualisation. RMIT Business.

- Perry, A. (1996). The rise and fall of strategic planning: reconceiving roles for planning, plans, planners. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 3(13), 275-278.

- Peter, M.K., & Jarratt, D.G. (2015). The practice of foresight in long-term planning. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 101, 49-61.

- Peterson, G.D., Cumming, G.S., & Carpenter, S.R. (2003). Scenario planning: a tool for conservation in an uncertain world. Conservation biology, 17(2), 358-366.

- Planellas, M. (2013). In search of the essence of strategy, a model for strategic management in three stages. ESADE Business School Research Paper, (250).

- Porter, M.E. (1991). Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strategic management journal, 12(S2), 95-117.

- Porter, M.E., & Advantage, C. (1985). Creating and sustaining superior performance. Competitive advantage, 167.

- Ram, C., Montibeller, G., & Morton, A. (2011). Extending the use of scenario planning and MCDA for the evaluation of strategic options. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 62(5), 817-829.

- Ramírez, R., & Selin, C. (2014). Plausibility and probability in scenario planning. Foresight, 16(1), 54-74.

- Ratcliffe, J. (2000). Scenario building: a suitable method for strategic property planning?. Property management, 18(2), 127-144.

- Rialland, A., & Wold, K.E. (2009). Future studies, foresight and scenarios as basis for better strategic decisions. Trondheim, December.

- Ringland, G., & Schwartz, P.P. (1998). Scenario planning: managing for the future. John Wiley & Sons.

- Rohrbeck, R., Battistella, C., & Huizingh, E. (2015). Corporate foresight: An emerging field with a rich tradition. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 101, 1-9.

- Roney, C.W. (2010). Intersections of strategic planning and futures studies: methodological complementarities. Journal of Futures Studies, 15(2), 71-100.

- Roxburgh, C. (2009). The use and abuse of scenarios. McKinsey Quarterly, 1(10), 1-10.

- Schoemaker, P. J. (1995). Scenario planning: a tool for strategic thinking. Sloan management review, 36(2), 25-50.

- Srinivasan, S. K. (2012). Managing uncertainty: The case for scenario planning in management education. Editorial Team, 21.

- Stone, A.G., & Redmer, T.A. (2006). The case study approach to scenario planning. Journal of Practical Consulting, 1(1), 7-18.

- Tibbs, H. (2000). Making the future visible: Psychology, scenarios, and strategy. Global Business Network.

- Van der Heijden, K. (2011). Scenarios: the art of strategic conversation. John Wiley & Sons.

- Van der Merwe, L. (2008). Scenario-based strategy in practice: a framework. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10(2), 216-239.

- Van der Merwe, L. (2008). Scenario-based strategy in practice: a framework. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10(2), 216-239.

- Vann, J., Jackson, S., Bye, A., Coward, S., Moayer, S., Nicholas, G., & Wolff, R. (2012, May). Scenario thinking: a powerful tool for strategic planning and evaluation of mining projects and operations. In Project Evaluation 2012: Proceedings. Project Evaluation Conference (pp. 5-14).

- Wack, P. (1985). Scenarios: uncharted waters ahead. Harvard Business Review September–October.

- Whittington, R., & Cailluet, L. (2008). The crafts of strategy. Long Range Planning, 41(3), 241-247.

- Wilburn, K.M., & Wilburn, H.R. (2011). Scenarios and strategic decision making. Journal of Management Policy and Practice, 12(4), 164-178.

- Wilkinson, A., & Eidinow, E. (2008). Evolving practices in environmental scenarios: a new scenario typology. Environmental Research Letters, 3(4), 045017.

- Wulf, T., Meissner, P., & Stubner, S. (2010). A scenario-based approach to strategic planning. Integrating Planning and Process Perspective of Strategy, Leipzig.