Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 2S

Role of Wag in Improving Saudi Efl Learners Cohesive Writing: An Exploratory Study in a Learner-centered Classroom Beyond the Four Walls

Kholoud A. Alwehebi, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University

Keywords

WhatsApp Group, Language Learning, EFL, Essay Writing

Citation Information

Alwehebi, K.A. (2022). Role of WAG in improving Saudi EFL learners’ cohesive writing: An exploratory study in a learner-centered classroom beyond the four Walls. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 21(S2), 1-13.

Abstract

The current compulsions in the academic dispensations all over the world have introduced monumental changes in the way teachers teach, and learners learn. This study examines one important aspect of this change: the use of mobile technology in enhancing the Saudi university-level EFL learners' skill in producing cohesive free writing pieces. The focus on cohesion in writing is a key area in EFL education that needs attention as it is seen as a casualty in these learners' writing samples where they are required to write beyond a few sentences. The study uses a specially created WhatsApp group to encourage supportive peer feedback as a tool in collaborative learning. The study was conducted with 117 first-year female students enrolled in both the Preparatory Year Program (PYP) and the English Department of Imam Abdul Rahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi Arabia. Using active messaging and voice messaging on WhatsApp, the participants were encouraged to help improve cohesion and find suitable topical sentences for the paragraphs in their peers' writing across a period of eight weeks, during which four exercises in 750 words each were undertaken. The writing genre used were the factual description of a person, description of a real event, description of an imaginary event, and an essay on participants' experiences during the intervention. A progress rubric was maintained by the researcher to chart the development of the participants’ cohesive writing skills across the eight-week-long study. An evaluative writing test was conducted at the end of the eight weeks, and results were compared with the average scores of the previous two writing tests conducted by the university. Descriptive statistics were used to conclude that participants' cohesive writing showed remarkable improvement post-intervention, while the last essay on their personal experience showed that collaborative work in the form of peer input is a strong, highly recommended aid in improving learners’ writing skills.

Introduction

In the new age language classroom, technology, its tools, and applications have assumed indispensable dimensions to successfully fulfill learner and market needs. This is so in the EFL and ESL classrooms, where teachers are hard-pressed to emulate high-tech teaching-learning models. The key element in this scenario is access to the internet and electronic devices, which are, anyhow, highly popular in the learner community given the excellent mobility and access to information that they offer. Moreover, flipped classroom or a classroom where the two components of learning, viz. learning of new materials and practice of these, are spread over in and out-of-class time, has become a compulsion given the current academic trends in post-Covid times. Teachers and students spend a substantial amount of time in school, and this ensures bonding as in other communities, only that this community is class restricted. However, the bonding so formed can be exploited for academic purposes with students connecting more readily with this community (Al-Ahdal & Alqasham, 2020; Al-Ahdal, 2020a, 2020b).

Mayer (2009) proposed a novel idea that knowledge acquired through multimodal means is more enduring, especially the visual and verbal channels, because it stimulates and strengthens the learners' retention. One of the biggest advantages of a flipped classroom is the scope for learners to fully collaborate with peers outside the class confines. Further, Briesmaster M., & Etchegaray 2017 stated that such classes offer flexibility to accommodate learner-centric pedagogies, including active learning and collaborative learning. In a study focusing on English collocations learning by Thai learners, Suranakkharin (2017) notably found that whereas the test results were comparable in traditional and flipped classrooms, the latter ensured a more enjoyable learning experience than the former and more encompassing collaboration when learners watched videos outside the classroom.

Cohesive Writing

Cohesion in writing has rightly been at the center stage of researchers' and language teachers' concern, given its centrality to comprehensible written output. Bahaziq (2016) claimed that cohesion in writing identifies a relationship between elements of a text where proper interpretation and understanding of one element depends on another. He (2020) noted in a study comparing English writing output by L1 and L2 learners of the language that cohesion plays an important role in making the writing clear, appropriate and comprehensible in text. Findings in this study indicated that L2 learners' writing showed a poor density of use of cohesive elements and sentence-initial use of conjunctions. What makes for cohesion was first spelled out by Halliday & Hasan (1994) in the following words:

Cohesion in English provides important new tools for linguistic analysis by delineating those semantic resources of the language which tie idea to idea to create texts. Unified passages are recognized as texts partly on the basis of mediating ties…

According to Halliday & Hasan (1994), five types of ties can be identified: reference, substitution, ellipsis, conjunction, and lexical cohesion. The gravity of their argument lies in the fact that it defines, among other things, cohesive analysis. The authors classified lexical cohesion into two broad categories: collocation (occurrence of two or more words that are usually used together); reiteration (reasserting the meaning of an item by exploiting lexical relationships).

Recent studies in cohesion in EFL writing have established that it is a challenge for L2 learners. Wahid & Wahid (2020) investigated this aspect of Saudi EFL learners' descriptive, process analysis, and argumentative essays. Analysis of output showed that they engaged in inappropriate and excessive use of pronouns and repeated lexical items to the extent that made their writing non-cohesive with negative effects on their structure and meaning. In a similar context but with Kuwaiti undergrads, Alzankawi (2017) used the Halliday-Hasan (1994) model to assess the writing of EFL learners. Once again, the graph was tipped in favor of overuse of certain cohesive devices, most notably reference, conjunction, and lexis. The author attributed the poor cohesion in learners’ writing to the practice of learning writing mainly to appear in exams and not as a communicative skill. Apparently, awareness of cohesion in writing can help L2 learners improve this aspect of their output.

The Learner-Centered Classroom

With or without technological intervention, language classrooms can be classified as teacher-fronted classrooms and learner-centered classrooms. Teachers will agree that at least theoretically, the most important component of the classroom is the learner. However, in a real classroom, more often than not, the learner gets eclipsed as the teacher struggles to fit in the planned lesson in the allotted time, achieve the curricular objectives, and over the syllabus already set for the day. Indeed these are real challenges that the teacher community has to grapple with. At the same time, a learner-centered perspective does not indicate that the teacher abdicates the classroom because even as a facilitator, the teacher has a role to play in the learning process. The essential difference, however, lies in the approach to language teaching. When seen as just another subject to be taught, it is inevitable for the teacher to focus on the content to be delivered with rarely any need for critical thinking on the students' part or even their participation for the teacher is, here, a source of information which is transferred to the learners. On the other hand, if it is seen as a language for communication, the teacher leads the learners onto a discovery of meaning by themselves, helping them listen, speak, read, and write better. In this situation, the text is only a means of developing these skills, not an end in itself. A learner-centered classroom, thus, focuses on both the learning and the learner, with teaching geared towards making the learner autonomous and independent. Language teaching research in recent years has been spearheading the learner-centric movement, the most important idea of which is the question of decision-making or learner autonomy. Such an approach also shifts the focus to learning which the main idea of the communicative language paradigm is also.

Literature Review: Technology in The EFL Classroom

Durgungoz & Durgungoz (2021) highlighted the efficacy of an instant messaging tool such as WhatsApp in creating a sustained learning environment for secondary school learners in Turkey. The study, spread over two years, concluded that out-of-class interaction improved significantly in learning through the WhatsApp group. What contributed to fostering this was the informal communication by the teacher. To gain a realistic idea of the success of the intervention, the study applied three methods for data collection: online observation, online documentation, and face-to-face interviews. Learner interactions showed that what the students really appreciated was the ease of use of the tool, anytime-anywhere accessibility, and increased interaction that contributed to better activity participation.

Perceptions play a central role in foreign language learning and hence the heightened role of motivation to learn. In a study with a relatively small population (N=29), Saritepeci, Duran & Ermis (2019) evaluated the efficacy of WhatsApp in preparing EFL learners for a national academic language exam. The study applied WAG (WhatsApp Group) to create a learning community for strictly reinforcement purposes of the taught content. Using semi-structured interviews at the end of the training, the study found certain key areas where the learners perceived benefits accruing from the WAG. These were broadly teacher-learner interaction, enhanced motivation, greater learner satisfaction, continuity of learning, and activity-based active learning opportunities.

Revision of new vocabulary by forming 'peer-chain' was found effective in a study with university students in Central Anatolia, to be noted that the participants had failed the mandatory proficiency exam at the beginning of the academic year. The researchers, Balci & Kartal (2021), employed a 'peer-chain' technique which is inspired by the constructivist theory that stresses the role of collaboration and cooperation with the use of ICT in enhancing learning. Results gathered from comparisons of pre and post-test scores were significantly varied for experimental and control groups. Moreover, post-test interviews with experimental group students showed positive perceptions towards the technique, leading to the conclusion that integrating WAG with peer-chain technique can be promising in EFL environments.

In another study, Farahani (2019) concluded that mobile mediated peer review groups were more focused on lexical resources, range of grammar use, and accurate writing in a course on academic writing with IELTS aspirants in Canada. The mobile app used in this study was Telegram. At the same time, another study with IELTS aspirants was conducted by Lestray (2020) with EFL learners in Indonesia. Out of the three parameters of mobile learning, that were measured, mobile learning was found to have supported the participants' learning experience to a large extent.

Benefits in English academic vocabulary for EFL learners using WhatsApp compared to the traditional methods were also reported by Bensalem (2018) in a study with Arab University learners. Learners in the study were encouraged to use the dictionary to learn new words, use them in sentences, and post them on the WAG. Pre and post-tests showed improved vocabulary in the experimental group as compared to the control group, which learned vocabulary using the paper and pencil method. In addition, learners' perceptions of the use of WAG as a vocabulary-learning tool were also assessed, which turned out to be positive. Clearly, the use of WhatsApp is efficacious for learning L2 vocabulary.

In a unique study, Nedungadi, Mulki & Raman (2018) set out to check how far WhatsApp mobile technology helped check absenteeism and ensure the achievement of learning outcomes in rural India. The study found that attendance issues are strongly related to the frequency of interaction which is high in the case of WAG. The focal areas of the study were increasing teacher effectiveness and student involvement in the learning process. The study also concluded that the model enhanced pedagogical output and enhanced overall student performance.

WhatsApp Group (WAG)

Many individuals make use of WhatsApp, a free smartphone messaging app that can be used on a number of different operating systems. There are many different types of media files that may be shared using WhatsApp. Messaging apps in WhatsApp and Facebook, are used by one billion people worldwide, making it the most popular online messaging service. After being started by ex-Yahoo employees in 2009, it rapidly expanded to 250,000 users. Facebook acquired the app in 2014 and it currently has over one billion users. WhatsApp offers a wide range of features to its users. One of them is group chat. Those who belong to WhatsApp groups share a residence where they may stay in contact and share information with one another at all times. The tools available allow students and teachers to communicate with one another. Discussion forums allow people to communicate, debate, and exchange pictures, videos, and other types of media. To help students improve their writing abilities both within and outside of the classroom, teachers may devise a variety of different exercises. WhatsApp Group conversations in the classroom offer many advantages. Instructors are more available and there are less privacy issues. Teachers who use WhatsApp while instructing may take on a more facilitative role.

WhatsApp audio and video calls use the phone's internet connection rather than cellular calling minutes, so users do not have to worry about expensive call fees. Capturing Photographs and videos may be sent and received instantly through WhatsApp's photo and video function, allowing users to share priceless moments. They include a built-in camera, so you can capture priceless moments on camera. Images and movies may be transmitted quickly through WhatsApp even if the connection is weak. This is a document that anybody may access and share. In this way, they may send things like PDFs, spreadsheets, presentations, or any other kind of multimedia without the need to utilize email or file-sharing programs. In addition, you may share 100 MB files with whomever you wish making it much easier to exchange critical information. This is the 153rd group chat conversation. Within a Group, members may interact with one other more easily by using group chat. Their ability to connect with those who important to them, such as family members or colleagues, is unsurpassed. It is possible for a group chat to have up to 256 users sending and receiving messages, images, and videos at the same time. The names of groups, notifications, and other features are all customizable by users. On a computer or the web, WhatsApp is an excellent tool for making connections with others. WhatsApp may be used on both a web browser and a desktop computer simultaneously. As long as users have an internet connection, they may communicate on whatever device they want. End-to-end encryption should be the default option for security reasons. WhatsApp allows its users to send and receive private messages with their loved ones. When a message or a call is encrypted end-to-end, no one can read or hear it, not even WhatsApp. Only users and those who interact with users may read or hear it. Voice Messages on WhatsApp in a chat room, users may leave voicemail messages by tapping on a voicemail item. They may greet his friends and relatives and tell stories that go on for a long time.

Research Context

In the new educational design, technology has pervaded every aspect of academics, and new tools are finding entry into the system with each passing day. Mpungose (2019) pointed out that the use of the Moodle e-learning management platform is mandated by the South African universities for first year students. However, as compared to WAG, the number of challenges in this is quite large. Attempting to supplement Moodle, the study found that students are keener on adopting a less formal e-learning platform such as WAG, also because they are very familiar with the use of the latter in day-to-day interactions with peers. The study participants were first-year students at a university, and data was collected through semi-structured interviews. In a review of literature on the use of WhatsApp in language learning, Kartal (2019) isolated keywords, sample sizes, positive language learning outcomes, populations, and duration of the study across 37 relevant research articles. These were identified over a four-phase procedure and reviewed systematically. Results indicated the popularity of WA in language learning along with a diversity of uses the tool was put to. Among other things, motivation and language attitudes showed enhancement as a result of WA use, learner autonomy was more assured, opportunities for interaction were not eh rise, and learning anxiety was reduced. Dumanauw (2018) assessed the efficacy of WA in teaching the writing of recount text to grade 10 learners. Using a pre-posttest design, the study showed that there was a positive influence of using WA on learners' recount text writing achievement.

Research Questions

This study aims to assess the efficacy of using WAG in a flipped classroom model to enhance Saudi university EFL learners’ cohesiveness in free writing. Since the participants are all connected on a WAG, individual input, and collaboration are both equally important in learner output. The study, accordingly, seeks to answer the following questions:

1. Is cohesion a casualty in the free English writing of the female Saudi EFL learners?

2. Can cohesion in free writing be enhanced using WAG?

Methodology

The study takes a quantitative approach by taking a convenience sample of 117 female Saudi EFL learners female students enrolled in both the Preparatory Year Program (PYP) and the English Department of Imam Abdul Rahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi Arabia. Using active messaging and voice messaging on WhatsApp, the participants were encouraged to (i) help improve cohesion with their inputs and (ii) find suitable topical sentences for the paragraphs in their peers’ writing across a period of eight weeks (at one exercise per two weeks) during which four exercises in 750 words each were undertaken. The writing genre used were the factual description of a person, description of a real event, description of an imaginary event, and an essay on participants' experiences during the intervention. A progress rubric was maintained by the researcher to chart the development of each participant's cohesive writing skills to be updated at the end of every two weeks when the learner submissions were made.

At the end of the first two weeks, when the learners completed the first writing, the researcher prepared a frequency distribution classifying all occurrences of cohesive devices as follows as per the classification suggested by Halliday & Hasan (1994):^

1. Reference

2. Ellipses

3. Substitution

4. Conjunction

5. Lexical cohesion

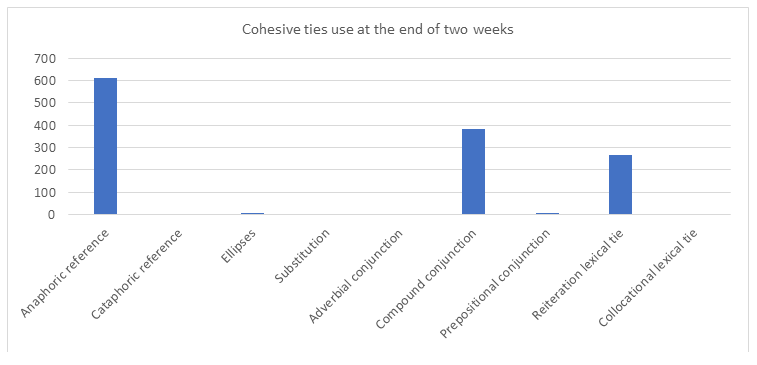

The following Table 1 sums up the frequency distribution of under and over use of cohesive devices.

| Table 1Frequency Distribution (N=117) Of Cohesive Devices In First Textual Production | |

|---|---|

| Cohesive Device | Total Occurrence |

| Anaphoric reference | 613 |

| Cataphoric reference | 4 |

| Ellipses | 7 |

| Substitution | 3 |

| Adverbial conjunction | 0 |

| Compound conjunction | 381 |

| Prepositional conjunction | 6 |

| Reiteration lexical tie | 267 |

| Collocational lexical tie | 0 |

Figure 1 below shows the graphical representation of this data, rather an interesting one. It is apparent that only three of the nine possible cohesive ties are used by the participants in their first writing sample. Another three are negligibly used, while the remaining three are not used at all.

Data Analysis and Results

Reference is a semantic relation and indicates replacing the subject with suitable pronouns, articles, comparatives, and demonstratives. As the name indicates, it is used to ‘refer back’ to someone or something. These have been broadly classified as Situational or Exophora, and Textual or Endophora. In the former, the reader needs to go out of the text or be in the know of the thing being referred to but not in the text, while in the latter, the text itself is the point of reference. Textual reference is further classified as anaphoric or cataphoric depending upon whether the reader needs to look back or ahead to identify the object being referred to. This implies that anaphoric reference is a kind of presupposition, but cataphoric reference is more abstract in nature. Cited below are two samples of underuse of reference in the data collected in the first text, factual description of a person, produced by the participants in the study.

i. Hamza is tall and thin. [Hamza] walks with a slight tilt of her head.

ii. Father always calls out to me when he comes home. It is what I love the most about [father].

The samples show that the participants are ignorant of the basic reference devices in English, which may be a result of limited writing practice. Since the researcher was also part of the WAG, she noticed that in the first two weeks, very few participants came forward to correct or collaborate; the few that did so mostly referred to internet sources to correct their peers' text or suggest better ways of expressing ideas.

Ellipses, as Halliday & Hasan (1994) pointed out, is an unnoticeable deletion because the item has been referred to earlier in the text. In other words, it is dropping items that are usually obvious. Further, the authors pointed out that ellipses ensure grammatical cohesion.

i. The teacher often helped us out of class as much as inside [the class].

ii. Yunus was my best friend, and [he] often proved his large-heartedness.

The samples from the first written text in this study point towards learners’ ignorance of ellipses as they display a tendency to over-use nouns or pronouns even where they can be dropped without any effect on the meaning of the sentence. It is apparent that poor exposure to English text (through reading a wide range of texts) leads to poor confidence in experimenting with their expression. Explicit instruction, however, can be the way forward to ensure they have a variety of expressions in their language repertoire.

Substitution, according to Halliday & Hasan (1994), is also a device of grammatical cohesion tie but is different from ellipses as it is not a dispensable component. It is defined as "a linguistic element that is not repeated but replaced by a substitute item." In the present study, it is a rarely used tie, and in all of the 117 samples of the first exercise, only three cases of its use could be found in the data. Two of these are quoted below:

i. He was very fond of burgers. Whenever he had any money, he had [one].

ii. The Principal was a perfectionist and saw to it that our teachers were [so], too!

The use of substitution calls for higher-order language use skills as the function of the substitute is purely structural, requiring of the user reasonable knowledge of the language. Halliday & Hasan (1994) classify these as Nominal, replacement by using a noun such as one, same, etc., Verbal, replacement by a verb, and Clausal, replacement by a clause connector such as, so, then, etc.

A conjunction is a grammatical tie but also includes some features of lexical cohesion. Halliday & Hasan (1994) pointed out that these "are cohesive not in themselves but indirectly, by virtue of their specific meanings; they are not primarily devices for reaching out into the preceding (or following) text, but they express certain meanings which presuppose the presence of other components in the discourse." The role of conjunctions is to make the sequence of events in a text logical and orderly by connecting immediate or successive thoughts, making the text more precise. In the data in this study, participants used only a few conjunctions, and there too, overly. These are 'and' and 'so.' Compound adverbial conjunctions, such as moreover, subsequently, further did not figure even once nor did prepositional expressions such as despite of, as a result of, etc. Writing samples are given below:

i. The beggar always sat in the same place. [And] the beggar soon became identified with the hotel itself.

ii. [So] they did not mind getting scolded every morning. [So] it made her angrier.

Participants' over-use of conjunctions and in sentence-initial place makes their text somewhat disjointed, quite contrary to the function of conjunction use. It is also apparent that they are aware or comfortable using only the simple adverbial conjunctions to the exclusion of compound and prepositional expressions, which would have required greater skill and exposure of language use.

Lexical ties have been categorized as reiteration and collocation by Halliday & Hasan (1994). Reiterative cohesion can be achieved by substituting lexical items with synonyms, hyponyms, or general words. Further, repetition, antonymy, and meronymy may also be used. Collocations, on the other hand, are lexical items "that regularly co-occur" (Halliday & Hasan, 1994). The relation between these words is lexico-semantic; that is, these words usually occur in the same lexical milieu, and some association between them exists. In the data set of this study, lexical ties are conspicuous by their total absence. The samples show that repetition of the noun or substitution thereof with simple pronouns is the most frequent. Correct and efficient use of collocation is indicative of very proficient language users as it places them close to native users because collocations combine words naturally. However, collocational competencies were found missing in the participants' first textual production in this study.

At the end of the first two weeks, the researcher had preliminary data on the use of cohesive devices in the participants' textual production. Being in the WAG formed with the participants, she encouraged them to work collaboratively in improving their peers' writing. Every time a participant posted some writing sample, she took asked the others to attempt improving it. This explicit elicitation was found to be useful as the participants became more active in the WAG and came up with novel suggestions of language use. While it is true that a large chunk of these came from internet sources, but the exercise still ensured that the platform was flooded with language use ideas. On average, every sample received between thirty to sixty-five responses, and at least 65% of all writing samples were reposted with improvements. As stated earlier, the researcher had kept the writing submission deadline at two weeks from the date of assigning the task, and three remaining tasks were analyzed at the end of four, six, and eight weeks. Table 2 below summarizes the occurrence of cohesive devices during these evaluations.

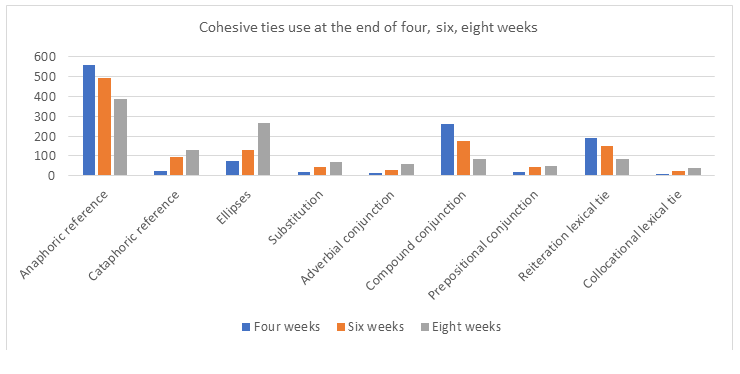

| Table 2 Evaluation Of Writing Samples At The End Of Four, Six, Eight Weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohesive device | Four weeks | Six weeks | Eight weeks |

| Anaphoric reference | 557 | 491 | 385 |

| Cataphoric reference | 23 | 96 | 128 |

| Ellipses | 75 | 131 | 264 |

| Substitution | 19 | 43 | 71 |

| Adverbial conjunction | 12 | 32 | 59 |

| Compound conjunction | 259 | 175 | 87 |

| Prepositional conjunction | 21 | 46 | 52 |

| Reiteration lexical tie | 191 | 149 | 87 |

| Collocational lexical tie | 11 | 23 | 42 |

When the data above was plotted graphically, the following picture emerged. Figure 2 explains the cohesive device use frequency at the end of four, six, eight weeks.

It is visible from the figure that with active participation on the WAG to work collaboratively outside the classroom on producing cohesive writing samples, there is a noticeable improvement in the use of a variety of cohesive ties. Further, ties that were overexploited at the end of the first two weeks appear to be less so, such as repetition for reiteration and compounding conjunctions, while those that were not used at all show use by the participants.

Using the data tabulated in Tables 1 and 2, the statistical significance for change in each of the nine cohesive ties used for text analysis in this study were calculated. In each of the cases, the outcome was >0.05, indicating the null hypothesis to be true since the only interventional measure here was collaborative peer work on the WAG. To further validate the findings of the study, an evaluative writing test for cohesive writing was conducted at the end of the eight weeks, and results were compared with the average scores of the previous two writing tests conducted by the university. The average group scores showed an increase of 34.72%, which is substantial. The last of the four free writing exercises was for the participants to enumerate upon their experience on using WAG to improve the cohesiveness of their writing. Content analysis of these 117 texts was conducted to isolate recurrent themes. These were found to be in favor of (i) peer support; (ii) increased interaction with the teacher (researcher in this case); (iii) fun learning; (iv) out-of-class learning; (v) autonomous learning. Generally, this paper presents the advantages of using WhatsApp Group (WAG) in the writing performance of Saudi EFL learners. They results showed that the use of WAG is an ideal Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) tool, which facilitates language skill enhancement of the students particularly on writing. This finding agrees with the previous results of investigation that for writing in English, students were especially interested by using WhatsApp groups. They were able to pick up new terminology and improve their grammar by joining the WhatsApp group discussion. This shows that WhatsAppgroup may be a useful educational tool, especially for pupils who need to improve their writing (Al-Ahdal & Algouzi, 2021; Al-Ahdal & Shariq, 2019; Arifani, 2019; Jafari & Chalak, 2016; Susanti & Tarmuji, 2016). The results of the present study research showed that students' writing skills improved significantly after participating in a WhatsAppgroup conversation. Due to this approach, students were more inclined to take part in online discussions. Even for English language learners, WhatsApp is an excellent teaching tool because of its wide appeal. Student benefits include: free opportunities to practice English language skills and components; a closer and more personal relationship with teachers; the ability to be a more social person while also improving; and a way to stay in touch with learners and make students available in their attempt to learn English. As a result, they will be more eager to learn the language since they'll feel more confident and self-sufficient. WhatsApp is also used by students outside of school hours. It helps students learn the language in days instead of weeks. They are allowed to read and write as many times as they want on the materials supplied by their teachers. When a student is stuck or perplexed by the course material, they may ask for help from their classmates and teachers through WhatsApp. The use of WhatsApp Group has the following features. With WhatsApp's messaging feature, Message, you can stay in touch with friends and family in a simple and secure manner. Users do not have to pay a dime to send messages to friends and family members. Instead of paying for SMS, users may use WhatsApp to send and receive messages for free.

The findings of the current study also highlight the positive attitudes of the participants toward the use of WhatsApp in learning new vocabulary. These results are in line with the findings reported by previous studies such as Muthmainnah (2020) who surveyed Arab EFL students in Oman. His participants believed that the most useful app for English language learning was WhatsApp. The same results were reported Al-Ahdal & Algasham (2021) on the role of WhatsApp in language classroom where the benefits of using WhatsApp to improved language skills of Saudi EFL students. The results of their study demonstrated that almost all participants acknowledged that the application of WhatsApp enhanced their motivation to read in English. In like manner, Al-Ahdal & Hussein (2020) also reported that WhastApp improved writing skills of EFL students in two universities in Saudi Arabia. The effectiveness of WhatsApp in enhancing the learners’ language skills that is reported in the current study can be attributed to different factors.

First of all, the novelty of the experience of using a smartphone app to complete classroom assignments has intrigued students and got them more involved in the learning process. They particularly liked the sense of immediacy, as they were able to send and receive messages instantly. A second possible factor could be the sense of virtual community that has been created between students and their instructor, on one part, and among students themselves through the use of the WhatsApp group chat. In such an environment, a special bond could have been created between the different members as it was the case of Saudi Experiment (Al-Ahdal & Alqasham, 2020; Al-Ahdal & Hussein, 2020; Al-Ahdal & Abduh, 2021). These studies argued that participants’ sense of belonging to a community of learning has prompted them to complete their assignments with more diligence in language learning.

Another plausible reason for the positive outcomes of the current study is that the use of WhatsApp has somehow liberated students who lack confidence to participate in class. As many studies have reported (Al-Ahdal, 2020; Al-Ahdal & Algouzi, 2021; Al-Ahdal & Shariq, 2019; Magulod, 2018; Magulod, 2019) Arab students typically experience high levels of anxiety while speaking and writing foreign languages in class. Using WhatsApp may have helped participants feel less inhibited and thus has boosted their confidence to be actively involved in the learning process and felt that it positively impacted their language performance. The same perception was shared by Turkish EFL learners who thought that using WhatsApp significantly impacted the students’ language acquisition by lowering EFL speaking anxiety (Han & Keskin, 2016).

A positive attitude about utilizing WhatsApp to learn a new language was found by this study's participants. Hashemifardnia, et al., (2018) found comparable findings in previous studies. In his study, participants said that WhatsApp was the most useful learning medium for them in order to improve their English language skills. A study conducted by Andujar & Salaberri-Ramiro (2021) showed that using WhatsApp to assist college students improve their English reading skills produced results comparable to those seen. Study results show that utilizing WhatsApp as a reading incentive tool increased motivation for almost all participants. According to one study, WhatsApp's effectiveness in raising students' vocabulary may be attributable to a mix of factors. It was easy to see that pupils were more interested in their education since they were intrigued by the novelty of using a smartphone app in class. They valued the sense of immediacy it offered since they could send and receive messages immediately. In addition, students and instructors have developed a sense of belonging via the use of WhatsApp group conversations, and among students themselves. Another reason for the positive findings of the research is that students who were previously scared to write and speak up in class are now more ready to do so as a consequence of the WhatsApp application. Researchers observed that students who communicated through WhatsApp were less inhibited and therefore more involved in the learning process. WhatsApp had a significant impact on their language acquisition since it reduced their degree of EFL speaking anxiety (Almogheerah, 2021; García-Gómez, 2020; Rahaded, et al., 2020; Robinson et al., 2015; So, 2016).

Conclusions

Halliday & Hasan (1994) pointed out that text could be made cohesive with judicious use of grammatical or lexical ties. The data generated and analyzed in this study indicates that WAG can be an effective mechanism to ensure peer collaboration in writing, enabling L2 language users to gain exposure to the varied use of cohesive devices to make writing effective. Accordingly, the study recommends the following.

Recommendations

Informal platforms using mobile technology should find a more conspicuous place in the EFL classroom, with teachers being more readily available to interact with learners. Academically oriented WhatsApp groups should be created with clearly stated learning objectives outlined, such as groups devoted to grammar learning, using idiomatic language, and so on. The bonus to make learning engaging lies with the teachers, and if conventional stereotypes need to be eliminated for the purpose, they should go ahead. Finally, institutions should ensure greater freedom of teachers in trying new pedagogies in their classes. As a result of these results, language teachers must think about incorporating WhatsApp into their vocabulary-learning strategies. Using WhatsApp, teachers may cover more vocabulary in less time than they would in a traditional classroom setting. Students who are timid or who would not engage in a face-to-face contact benefit from virtual communication as well. In order to keep students focused on the work at hand, teachers must set certain guidelines for utilizing WhatsApp successfully. Students tend to spend a lot of time talking on WhatsApp and forget about its original function. As a result, teachers must closely supervise their students to get the most out of online learning.

Limitations of the Study

This study has a slew of problems that need to be addressed. The research began with a small sample size. This means that any conclusions drawn from the research should be interpreted with caution. Second, the study was restricted to general terms. There is a chance that some students had higher results because they practiced more. To further understand how WhatsApp affects language learning, more studies are needed. It is a good idea to study other than writing which is vocabulary and speaking in a variety of subject areas, such as technical English. Research on the effect of WhatsApp on student vocabulary retention should be conducted soon after this study concludes. Students should be tested after the experiment to determine whether they can remember the new words they learnt.

References

Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H. (2020a). Using computer software as a tool of error analysis: Giving EFL teachers and learners a much-needed impetus. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change (Scopus-indexed), 12(2), 418-437.

Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H. (2020b). Ebook interaction logs as a tool in predicting learner performance in reading.Asiatic: IIUM Journal of English Language and Literature, 14(1), 174-188.

Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H., & Abduh, M.Y.M. (2021). English writing proficiency and apprehensions among Saudi College students: Facts and remedies.TESOL International Journal (Scopus-indexed), 16(1), 34-56.

Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H., & Algouzi, S. (2021). Linguistic features of asynchronous academic netspeak of EFL learners: An analysis of online discourse.The Asian ESP Journal, 17(3.2), 9-24.

Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H., & Alqasham, F.H. (2020). WhatsApp in language classroom: Gauging Saudi EFL teachers' roles and experiences.Opcion (Scopus-indexed), 36, 1667-1680.

Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H., & Alqasham, F.H. (2020). Saudi EFL learning and assessment in times of Covid-19: Crisis and beyond.Asian EFL Journal, 27(43), 356-383.

Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H., & Hussein, N.M.A. (2020). WhatsApp as a writing tool in EFL classroom: A study across two universities in Saudi Arabia.Asian EFL Journal (Scopus-indexed), 27(3.1), 374-392.

Crossref , GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H., & Shariq, M. (2019). MALL: Resorting to mobiles in the EFL classroom.The Journal of Social Sciences Research, 90-96.

Almogheerah, A. (2021). Exploring the effect of using WhatsApp on Saudi emale EFL students' idiom-learning.Arab World English Journal (AWEJ), 11(4), 328-350.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Alzankawi, M. (2017). Kuwaiti undergraduate problems with cohesion in EFL writing. In Proceedings of International Academic Conferences (No. 5807931). International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Andujar, A., & Salaberri-Ramiro, M.S. (2021). Exploring chat-based communication in the EFL class: Computer and mobile environments.Computer assisted language learning, 34(4), 434-461.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Arifani, Y. (2019). The application of small whatsapp groups and the individual flipped instruction model to boost EFL learners’ mastery of collocation.CALL-EJ, 20(1), 52-73.

Bahaziq, A. (2016). Cohesive devices in written discourse: A discourse analysis of a student's essay writing. English Language Teaching, 9(7), 112-119.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Balci, Ö., & Kartal, G. (2021). A new vocabulary revision technique using WhatsApp: Peer-chain. Education and Information Technologies, 1-21.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Bensalem, E. (2018). The impact of WhatsApp on EFL students’ vocabulary learning.Arab World English Journal, 9(1), 23-38.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Briesmaster, M., & Etchegaray P. (2017). Coherence and cohesion in EFL students’ writing production: The impact of a metacognition-based intervention.Íkala, 22(2), 183-202.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Conde, M.Á., Rodríguez-Sedano, F.J., Rodríguez-Lera, F.J., Gutiérrez-Fernández, A., & Guerrero-Higueras, Á.M. (2020). Assessing the individual acquisition of teamwork competence by exploring students’ instant messaging tools use: The WhatsApp case study. Universal Access in the Information Society, 20(3), 441-450.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Dumanauw, A., & Salam, U. (2018). The use of WhatsApp application to teach writing of recount text. Journal of Equatorial Education and Learning, 7(12).

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Durgungoz, A., & Durgungoz, F.C. (2021). “We are much closer here”: Exploring the use of WhatsApp as a learning environment in a secondary school mathematics class.Learning Environment Research, 1-12.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Farahani, A.A.K., Nemati, M., & Montazer, M.N. (2019). Assessing peer review pattern and the effect of face-to-face and mobile-mediated modes on students’ academic writing development. Language Testing in Asia, 9(1), 1-24.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

García-Gómez, A. (2020). Learning through WhatsApp: Students’ beliefs, L2 pragmatic development and interpersonal relationships.Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-19.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Halliday, M.A.K., & Hasan, R. (1994). Cohesion in English. London: Longman.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Han, T., & Keskin, F. (2016). Using a mobile application (WhatsApp) to reduce EFL speaking anxiety.Gist: Education and Learning Research Journal, 12, 29-50.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hashemifardnia, A., Namaziandost, E., & Rahimi, E.F. (2018). The effect of using WhatsApp on Iranian EFL learners’ vocabulary learning.Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 5(3), 256-267.

He, Z. (2020). Cohesion in academic writing: A comparison of essays in English written by L1 and L2 university students. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 10(7), 761-770.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Jafari, S., & Chalak, A. (2016). The role of WhatsApp in teaching vocabulary to Iranian EFL learners at junior high school.English Language Teaching, 9(8), 85-92.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Kartal, G. (2019). What’s up with WhatsApp? A critical analysis of mobile instant messaging research in language learning. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 6(2), 352-365.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Lestray, S. (2020). Perceptions and experiences of Mobile-assisted language learning for IELTS preparation: A case study of Indonesian learners.International Journal of Information and Education technology, 10(1) 67-73.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Magulod Jr, G.C. (2018). Innovative learning tasks in enhancing the literary appreciation skills of students.SAGE Open, 8(4).

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Magulod Jr, G.C. (2019). Learning styles, study habits and academic performance of Filipino University students in applied science courses: Implications for instruction.Journal of Technology and Science Education, 9(2), 184-198.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Mayer, R.E. (2009). Multimedia learning, (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press.

Mpungose, C.B. (2020). Is moodle or WhatsApp the preferred e-learning platform at a South African university: First year students’ experiences.Education and Information technology, 25.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Muthmainnah, N. (2020). EFL-writing activities using WhatsApp group: Students’ perceptions during study from home. LET: Linguistics, Literature and English Teaching Journal, 10(2), 1-23.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Nedungadi, P., Mulki, K, & Raman, R. (2018). Improving educational outcomes & reducing absenteeism at remote villages with mobile technology and WhatsApp: Findings from rural India.Educational Information Technology, 23, 113-127.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Rahaded, U., Puspitasari, E., & Hidayati, D. (2020). The impact of Whatsapp toward uad undergraduate students’ behavior in learning process.International Journal of Educational Management and Innovation, 1(1), 55-68.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Robinson, L., Behi, O., Corcoran, A., Cowley, V., Cullinane, J., Martin, I., & Tomkinson, D. (2015). Evaluation of Whatsapp for promoting social presence in a first year undergraduate radiography problem-based learning group.Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, 46(3), 280-286.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Saritepeci, M., Duran, A., & Ermis, U.F. (2019). A new trend in preparing for foreign language exam (YDS) in Turkey: Case of WhatsApp in mobile learning. Education and Information Technologies, 24(5), 2677-2699.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

So, S. (2016). Mobile instant messaging support for teaching and learning in higher education.The Internet and Higher Education, 31, 32-42.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Suranakkharin, T. (2017). Using the flipped model to foster Thai learners’ second language collocation knowledge. 3L: Language, Linguistics, Literature®, 23(3).

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Susanti, A., & Tarmuji, A. (2016). Techniques of optimizing WhatsApp as an instructional tool for teaching EFL writing in Indonesian senior high schools.International Journal on Studies in English anguage and Literature (IJSELL), 4(10), 26-31.

Wahid, R., & Wahid, A. (2020). A study on cohesion in the writing of EFL undergraduate students. Journal on English Language Teaching, 10(1), 57-68.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Zhang, J. (2018). The effect of strategic planning training on cohesion in EFL learners’ Essays. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 34(6), 554-567.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Zulkanain, N.A., Miskon, S., & Abdullah, N.S. (2020). An adapted pedagogical framework in utilizing WhatsApp for learning purpose. Education and Information Technologies, 25(4), 2811-2822.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Received: 27-Nov-2021, Manuscript No. asmj-21-9215; Editor assigned: 04-Dec-2021, PreQC No. asmj-21-9215 (PQ); Reviewed: 18-Dec-2021, QC No. asmj-21-9215; Revised: 28-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. asmj-21-9215 (R); Published: 09-Jan-2022