Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Strategic Anxiety: The Influence of Organizational Conspiracy Theory Beliefs and Employee's Withdrawal

Ali Razzaq Chyad AL-Abedi, University of Kufa

Laith Latif AL-Shimmery, University of Kufa

Abstract

In this study, we investigate the effect of organizational conspiracy theory (OC) beliefs on strategic anxiety (STA) through the mediating role of employee withdrawal (HRW) within the organization related to the Department of Homeland Security in the Maysan Governorate in mitigating/enhancing job insecurity. Communication within an organization is often negatively associated with job insecurity, particularly in turmoil and uncertainty; We suggest that this security department depends on the employee's status and whether the employees work in a fair procedural institution. In a survey of 251 police officers, we measured three key variables: organizational conspiracy theory (OC) beliefs, strategic anxiety (STA), and employee withdrawal (HRW). Dimensions of employee withdrawal as a mediator component include physical withdrawal, psychological withdrawal. As for the independent variable, strategic anxiety fears the future, social unrest, threats, and competitive competition. The results suggest a "partial effect" of employee withdrawal on the relationship between organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety. These effects were less pronounced for employees who perceived managers to be more procedurally fair. The findings of our study highlight that only procedurally business environments can help ensure that employees do not passively respond to organizational attempts at open communication when faced with uncertain contexts.

Keywords:

Organizational Conspiracy Theory, Employee's Withdrawal, Strategic Anxiety

JEL Classification Code:

E16, H83, M41, Q56

Introduction

The economic turmoil that occurs today in the organizations has led to a reduction in the size of the workers through layoffs, mergers, and bankruptcy (Amusawi, Almagtome & Shaker, 2019). These factors cause hundreds of thousands of workers to lose their jobs or millions of workers being transferred to unfamiliar tasks within their companies, wondering about the period for which they will be employed. Besides the pressures they face from the management policies and the feeling that they have to work longer in more complex jobs to maintain their jobs and remain in their current economic situation. Therefore, the workers at all levels face increased stress, anxiety, and uncertainty due to work-related concerns and social anxiety (Sunil & Rooprai, 2009). Strategic anxiety represents a threat and unpredictable fears specifically. It may be a future mood activated by a distant and potential danger that may result in frequent disturbances, reflecting on the workers and society. Specific phobias and social phobias, agoraphobia and panic disorder, general fear and obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and body disorders are also deemed anxiety disorders (Muschalla, 2009). Corporate conspiracies are a pervasive social phenomenon that leads many ordinary people to believe that social events such as economic failure, natural disasters, and wars result from wicked schemes orchestrated by influential individuals and organizations.

Furthermore, there has been a notable surge in research into the social sciences over the last decade that has focused on this mindset, such as (Ahmed, Vidal-Alaball, Downing & Seguí, 2020; Craft, Ashley & Maksl, 2017; Gerts et al., 2021; Su, Lee, Xiao, Li & Shu, 2021; Tangherlini, Shahsavari, Shahbazi, Ebrahimzadeh & Roychowdhury, 2020). As a result, the research activities have yielded a wealth of findings, which are experimentally related to conspiracy theories and healthier decisions that have resulted in a decline in civic integrity, discord, and extremism. This research has primarily focused on macro-level conspiracy theories, which have been described as questionable beliefs about geopolitical decision-making that often result in influential leaders, ethnic groups, or whole industries and this regard (for example, the oil industry or the pharmaceutical industry….etc).

Nonetheless, conspiracy theories suggest that companies are always micro and variable, and workers may be suspicious of the idea that administrators may actively conspire to achieve nefarious objectives (J.-W. van Prooijen & de Vries, 2016). Many studies have been conducted to investigate the aspects related to human resources withdrawal. Among these studies is the study (Mobley, 1977), which sets some precedents for the individuals working in the organizations. For example, the employee turnover decision includes the sequence of behaviors that lead to the employee leaving the organization. Other examples of these precedents are the current job evaluation, the ideas of the departure, the assessment of the employment's alternatives, the evaluation of benefits' loss.

Furthermore, the intention of searching for employment alternatives, followed by the actual search and comparison of the other options to the employment for the current job and the behavioral definition of the withdraw. Job satisfaction indirectly affects the turnover rate through other variables such as the thinking of the withdrawal, the search for alternatives and their evaluation, and the intention of leaving the organization. So the researchers were able to demonstrate that leaving the organization had the only effect on the employee withdrawal behavior.

Moreover, these results proved that job attitudes affect human resources withdrawal (Quinones, 2002). Hulin (1991) has defined human resource withdrawal as a set of the dissatisfied behaviors of the individuals to avoid a work situation. The human resource withdrawal also represents the voluntary physical and psychological withdrawal of the employees in organizations, such as the voluntary employee delay, absenteeism, and work turnover described in the studied withdrawal behaviors. Therefore, what is mentioned above, will lead us to clarify the features of the actual picture faced by leaders in the security institutions, represented by the strategic anxiety that detects the areas of vulnerability. The fear and psychological and social disturbances lead to dire consequences, accordingly. We need effective strategies to leave the traditional and hierarchical practices that have become old and a harmony with the changes to deal with the fear of the future and social unrest, besides the threats and competitive conflict (Al-Abedi, 2021).

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Recent years have witnessed increased people's interest in the psychological elements involved with belief in conspiracy theories (see Cassese, Farhart, & Miller, 2020; Federico, Williams, & Vitriol, 2018; Miller, 2020). The conspiracy theories attribute significant political and social events to powerful and harmful groups (Green & Douglas, 2018). Conspiracy theories often attempt to understand the ultimate causes of substantial social and political phenomena as covert operations orchestrated by influential and detrimental forces. On the other hand, conspiracy theories are prevalent in today's political climates and are far from becoming a new phenomenon (Douglas & Sutton, 2018). The term "conspiracy" often refers to the work of a large organization, technology, or system. It is a powerful lewd entity so dispersed that it represents the traditional counter-conspiracy theory. In other words, a conspiracy means a wide range of social disciplines and controls (Roukis, 2006). The concept of "Organizational Conspiracy" refers to influential forces inside organizations working behind the scenes to accomplish some evil. Managers can, for example, recruit a candidate who is similar to them for a job or function and plot to fire an employee from the company (Douglas & Leite, 2017). Corporate conspiracy can be characterized as the interpretative beliefs of employees who complain about their bosses, subordinates, or coworkers and secretly meet to accomplish aims commonly regarded as vicious and evil (van Prooijen & de Vries, 2016). Employee withdrawal is considered to be one of the destructive attitudes associated with human resource management. The withdrawal represents a segment of the employees who avoid overloading the work environment (Carpenter & Berry, 2017). How an employee who is unhappy with their job condition reacts can be characterized as withdrawal behaviors. It is clear that these responses do not positively contribute to the success of job activities, and a selection of volunteer actions other than the additional tasks are regarded as vital to organizational effectiveness (Kanungo & Mendonca, 2002). Withdrawal behaviors can be defined as a physical and psychological separation of the employee from work and the organization. Still, at the same time, he is keeping his role at work and his organizational membership. These behaviors include the volunteer delay of the employee, absenteeism, negligence, and intention of leaving the organization (Rurkkhum, 2018).

Personnel turnover is regarded as both a significant challenge for an organization and a fascinating subject. However, before workers plan to leave organizations, their withdrawal behavior can be expensive. It is calculated that organizations lose a significant amount of money in direct and indirect expenses due to withdrawal behavior issues. During a study of the strategic anxiety literature, it was observed that anxiety and depressive disorders are among the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in the world, affecting millions of people in many facets of their everyday lives and that surveys suggest that about a third of the population suffers from these disorders (Vignoli, Muschalla & Mariani, 2017). Strategic anxiety is a psychological issue studied from various perspectives, one of which is anxiety on the general public. Numerous people experience increased anxiety as a result of their employment. According to a recent survey of over 1,000 participants, (70 percent ) of those have experienced strategic anxiety at work, with more than (40 percent) of them experiencing tension (Mannor, Wowak, Bartkus & Mejia, 2016). Generally speaking, strategic anxiety has been broadly placed on the "dark side." As a result, anxious individuals have hypersensitive perceptual schemes that perceive the situations as threatening. They constantly scan the environment for the signs of threat that make them vulnerable to escalating re-flections. The anxious individuals display a range of information-processing processes, but at the same time, they mentioned the related information as threats. The worried individuals also have self-doubt regarding managing the threat situations and a lack of confidence in their capabilities (Gavin, Reisdorfer, Zanetti & da Silva Gherardi-Donato, 2017).

Nature refers to the belief that Organizational conspiracy theories represent a systemic way of collecting facts, contributing to the interpretation of threatening events as the expected result of nefarious plots. As a result, conspiracy theories have an analytical purpose linked to the internal mechanisms of making sense of the universe to perceive it as ordered, conceptual, and inevitable. These sensory-making mechanisms are at the heart of the perceptual "social disruption," which can be described as a suspicious mind condition marked by a possible hyper-vigilance of the purpose and hostility toward others, which causes anxiety. These points have been reused in academic analysis that recognizes natural enemies that can be blamed for a threatening occurrence useful in its enforcement. It represents an ordeal of acknowledging the presence of unpredictable and out-of-control causes, where we always anticipate immoral acts and actions that can be remembered. These facets combine to provide a model state in which corporate conspiracy theories can be used to reintroduce a sense of balance and the ability to forecast the consequences of risky social practices. Thus, social disturbances and anxiety-producing activities occur, consistent with the ideas and dreams of most research about the relationship's substance (Kbelah, Amusawi & Almagtome, 2019; Van Prooijen & Jostmann, 2013). One of the discoveries related to the relationship between the organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety is that the belief in the organizational conspiracy theory leads to strategic stress. That belief in conspiracy theories is founded on an implicit conspiratorial ideology that can be predicted using various behavioral and situational factors. According to the basic idea, such a conspiratorial attitude is mainly active in ambiguous circumstances that challenge or trigger anxiety.

In general, workers' confidence in organizational conspiracy theories was related to their ability to understand the social world, where ambiguous threat events have been shown to trigger thought processes that cause fear and enhance comprehension of the events. This feeling is the essence of paranoia and suspicion (Macovei, 2016). The empirical research supports this distressing effect and the uncertainty caused by circumstances related to the belief in the organizational conspiracy theories. It has been shown that the reason for the conspiracy beliefs is due to people's motor motives (J.-W. Van Prooijen & van Dijk, 2014). Furthermore, when people experience a lack of control, they are much more likely to believe in conspiracy theories (Sullivan, Landau & Rothschild, 2010; van Prooijen & Acker, 2015; Whitson & Galinsky, 2008). Finally, there is a clear consensus in the research literature that conspiracy theories gain traction, especially in adverse and ambiguous social situations that create strategic anxiety for businesses. The following study hypotheses were established based on the above arguments:

H1: Organizational conspiracy theory has a positive effect on physical withdrawal.

H2: Organizational conspiracy theory has a positive effect on Psychological Withdrawal.

H3: Organizational conspiracy theory has a positive effect on employee's withdrawal.

H4: Organizational conspiracy theory has a positive effect on strategic anxiety.

This idea is supported by some recent research, which indicates this belief in the corporate conspiracies caused by authoritarian leadership and non-interference is related to employee withdrawal from the organization (Douglas & Leite, 2017). The belief in the corporate conspiracy can predict the workers' results, which leads to their aversion from the social system in which they are working and their psychological and behavioral separation from the organization. These findings may be extrapolated into the organizational context. Employees will be unable to affiliate their identification with the organization if they feel that their influential leaders are working against them. Similarly, they are more likely to leave the organization because they think it is infested with corporate conspiracies. These findings suggest that corporate conspiracy theories significantly impact workers' commitment to the organization and their desire to leave their work (van Prooijen & de Vries, 2016). Withdrawal behaviors are defined as behaviors that involve physical withdrawal, such as absenteeism and labor turnover. Organizations are particularly encouraged to consider these patterns because they result in high costs. As a result, withdrawal behaviors have become important research topics in the area of human resource management. Steers and Rhodes (1978) created a process model in which worker satisfaction and organizational commitment became critical factors in employee involvement. It is an example of human resource management studies looking at withdrawal habits. Despite these studies, the scientific literature on the association between withdrawal practices and strategic anxiety remains mixed and, at best, moderate (Falkenburg & Schyns, 2007). The meaning refers to a systemic method of interpreting information that leads to solving threatening activities as the desired result of nefarious intrigues. As a result, conspiracy beliefs act as an explanatory function linked to the mechanisms of mental reasoning that seek to view the world as orderly, conceptual, and predictable. In reality, these sense-making mechanisms are assumed to be at the center of "social disruption" of awareness. It is described as a suspicious state of mind marked by a potentially malicious hyper-vigilance toward those causing the fear. These points resurface in scientific analysis that recognizes natural enemies as the cause of a threatening occurrence and is successful in its regulation. It represents an ordeal of acknowledging the presence of unpredictable and out-of-control reasons, and we often predict immoral acts and actions that can be identified. These considerations combine in a paradigm that notes that corporate conspiracy theories can be practical to reinstall the sense of order. The capacity to forecast the effects of dangerous social activities, causing social disturbances events that trigger and. As a result, this research assumes that organizational conspiracy theory significantly affects strategic anxiety mediated by employee withdrawal. As a result, the following hypotheses can be made:

H5: There is a mediator role of employee withdrawal in the relationship between organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety.

H6: There is a mediator role of physical withdrawal in the relationship between organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety.

H7: There is a mediator role of psychological withdrawal in the relationship between organizational conspiracy theory and Strategic Anxiety.

Data and Method

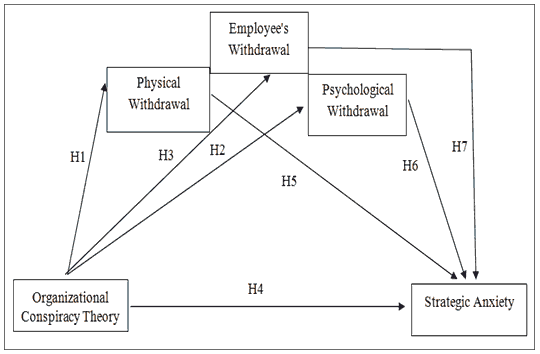

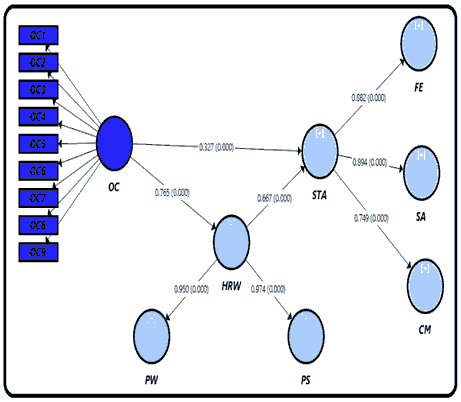

Figure 1 shows a theoretical framework that illustrates how organizational conspiracy theory influences an employee's withdrawal's strategic anxiety mediator effect. Narcissistic leadership theory and corporate events conspiracy and social classification theory has been an effects model that applicable theoretical, conceptual framework (Al-Fatlawi, Al Farttoosi & Almagtome, 2021; Aljawaheri, Ojah, Machi & Almagtome, 2021; Douglas & Leite, 2017; Hameedi, Al-Fatlawi, Ali & Almagtome, 2021).

The data presented in this paper were collected as part of an analysis to see whether there was a connection between organizational conspiracy theory (OC) and strategic anxiety (STA). In Iraq, a survey of police officers was conducted. A sampling method was used to identify the sample (N = 251), which is made up of police officers from the Iraqi province of Maysan. The data in this paper were obtained as part of a Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis. Smart-PLS was used to analyze the PLS-SEM used in 90% of studies related to organizational conspiracy theories and employee withdrawal.

Results

The Structural Model Measurement

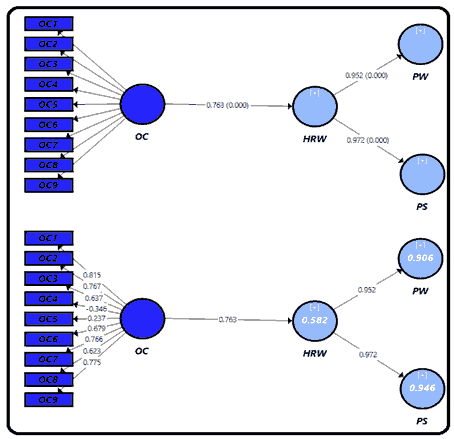

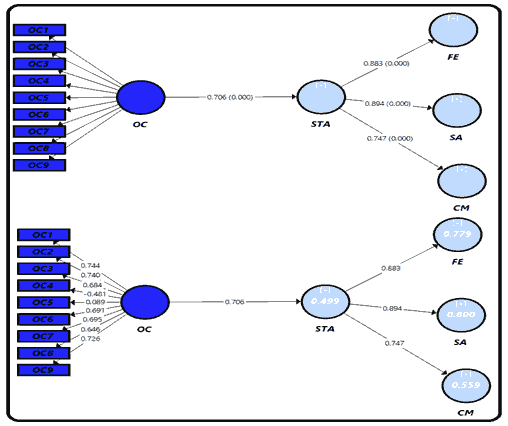

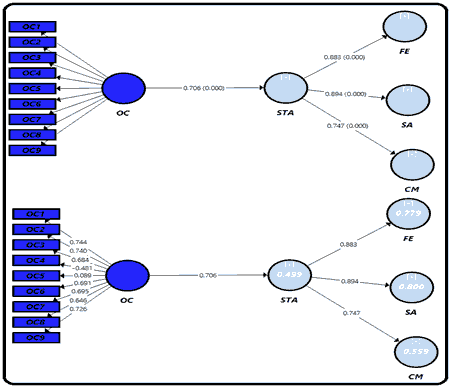

The hypotheses conceptual method is verified using a structural model to evaluate the interaction between latent variables (Joe F Hair Jr, Sarstedt, Hopkins & Kuppelwieser, 2014). Regarding the measurement model analysis, the present study investigates the systemic to determine the value of path coefficients (Joseph F Hair Jr, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). Hypotheses (H1), (H2), (H3), and (H4) were all accepted, implying that organizational conspiracy theory (OC) has a positive impact on employee withdrawal (HRW) and can increase strategic anxiety (STA), as seen in Figures 2, 3 and 4 Table 1.

Figure 2: Coefficients of Determination (R2) Between Organizational Conspiracy Theory and Employee's Withdrawal

Figure 3: Coefficients of Determination (R2) Between Organizational Conspiracy Theory and (Physical (PW), Psychological (PS)) Withdrawal

| Table 1 Results of Direct Effect Hypothesis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Original Sample (O) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | R2 | T Statistics (O/STDEV) | P-Value |

| (H1) OC -> PW | 0.787 | 0.021 | 0.62 | 36.855 | 0.000 |

| (H2) OC -> PS | 0.731 | 0.028 | 0.53 | 26.237 | 0.000 |

| (H3) OC -> HRW | 0.763 | 0.025 | 0.58 | 30.469 | 0.000 |

| (H4) OC -> STA | 0.706 | 0.026 | 0.50 | 13.30769 | 0.000 |

The Moderating Variable Role

Hypotheses (H5), (H6), and (H7) are expected to be able to explain the moderation study of Employees' withdrawal behaviors about the organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety. As the direct impact relationship between organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety can be explained, the analysis assumes a significant effect relationship between organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety through the moderating variable of employee withdrawal. The indirect effect of organizational conspiracy theory on strategic anxiety will be examined utilizing path analysis and the employee's withdrawal. The path analysis method consists of two conditions (Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle & Mena, 2012). The first is that the indirect effect of the organizational conspiracy theory on strategic anxiety through employee withdrawal is significant. The second condition is to define the upper and lower limits of trust (Bootstrapped Confidence Interval), that it is not these intersect zero. The results Table 2 that the direct impact relationship of the organizational conspiracy theory in strategic anxiety (0.327) P-Value=0.000, but it is less than the indirect effect relationship of (0.51), which reflected the effect of employee's withdrawal variable that mediates the influence relationship between the organizational conspiracy theory. The strategic anxiety affects the value of the (a) path between the organizational conspiracy theory in employee's withdrawal was (0.765), while the path (b) that showed the relationship of the effect of employee's withdrawal in the strategic anxiety was (0.667), the value of (T) Which tests the significance of the indirect effect (19.11), which is significant when compared of (1.69). The test results can be illustrated as in Figure 5 and Table 2.

| Table 2 Moderating Sub-Variables Effect |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficient | t-Statistics |

| (H5) | OC for HRW ----> STA | 0.51 | 19.11 |

| (H6) | OC for PW ----> STA | 0.32 | 23 |

| (H7) | OC for PS ----> STA | 0.38 | 12.07 |

Conclusions and Discussion

The findings indicate in Table 2 that the direct influence relationship of the organization-al conspiracy theory in strategic anxiety (0.177) P-value=0.000. Still, it is less than the in-direct effect relationship of (0.32), which reflected the effect of the physical withdrawal variable that mediates the influence relationship between the organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety. The value effect of the (a) path between the organizational conspiracy theory in the physical withdrawal (0.784), while path (b) showed the effect of the physical withdrawal effect in the strategic anxiety (0.402), the value of (T), which tests the significance of the indirect effect (19.11), which is significant when compared of (1.69). The resulting Table 2 also that the direct influence relationship of the organizational conspiracy theory in strategic anxiety (0.177) P-value=0.000. Still, it is less than the indirect effect relationship of (0.38), which reflected the psychological withdrawal variable that mediates the influence relationship between the organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety. The value effect of the (a) path between the organizational conspiracy theory in the physical withdrawal (0.722), while path (b) showed the effect of psychological withdrawal effect in the strategic anxiety (0.525), the value of (T), which tests the significance of the indirect effect (12.07), which is significant when compared of (1.69). Therefore, hypotheses (H1), (H2), (H3), and (H4) are supported.

The results indicate "a Partial Influence" of withdrawal of employees withdrawal in the relationship between the organizational conspiracy theory and strategic anxiety. It seems that the Maysan Governorate Police Directorate leaders feel that employees' departure caused by factors increase the strategic pressure that a significant reason related to organizational conspiracy theory beliefs. There is a possibility to know the indirect effect relationship through employees' withdrawal employees to the effect of Organizational conspiracy theory increasing for leaders' strategic anxiety phenomenon. Additionally, The leader's beliefs of organizational conspiracy theory resulting from the lack of credibility and transparency and work-related issues and their disappearance of some strict information. In general, this study examines how Organizational conspiracy theory affects strategic anxiety through the moderating role of employee withdrawal. It was concluded that the Organizational conspiracy theory has a significant positive effect on strategic concern for security leaders. Three variables were examined in the Maysan Governorate Police Directorate, one of the Iraqi Ministry of Interior directorates with security. Therefore, the results of this study can be used in specific areas that are not generalized. The study measurement tool by the questionnaire, which is often subject to individual bias, shows answers and results. It reflects their lack in the directions of the Maysan Governorate Police Directorate and studying research variables in other countries using new measures to reach different results. The study's sample was allocated to police officers investigating in Iraq's province. As a result, the officers' sample could not be reflective of all police forces in Iraq. Second, the present analysis focuses on information provided by individuals.

Conspiracy theories concerning social events have become common, and people's political, health, and environmental actions are affected by their beliefs in these ideas. Though little is known, we know that people's daily working lives are affected by conspiracy theories. To test this prediction, we sought to discover if the idea that conspiracy theories about the workplace exist will raise the intention to quit one's job. To develop the hypothesis mentioned above, we concluded that people who believe in such organization conspiracy theories are less committed to their work and less satisfied with their jobs.

References

- Ahmed, W., Vidal-Alaball, J., Downing, J., & Seguí, F.L. (2020). Dangerous messages or satire? analysing the conspiracy theory linking 5g to covid-19 through social network analysis. J. Med Internet Res. https://doi.org/10.2196/preprints.19458

- Al-Abedi, A.R. (2021). How the organizational envy effects on organization's brilliance? the moderating role of contextual leadership intelligence. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), 12(4), 665-673. https://doi.org/10.17762/turcomat.v12i4.551

- Al-Fatlawi, Q.A., Al Farttoosi, D.S., & Almagtome, A.H. (2021). Accounting information security and IT governance under COBIT 5 framework: A case study, webology, 18(2), 294-310.

- https://doi.org/10.14704/web/v18si02/web18073

- Aljawaheri, B.A.W., Ojah, H.K., Machi, A.H., & Almagtome, A.H. (2021). COVID-19 Lockdown, earnings manipulation, and stock market sensitivity: An empirical study in Iraq. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 8(5), 707-715. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no5.0707

- Almusawi, E., Almagtome, A., & Shaker, A.S. (2019). Impact of lean accounting information on the financial performance of the healthcare institutions: A case study. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 14(2), 589-599. https://doi.org/10.36478/jeasci.2019.589.599.

- Çal??kan, Ö. (2019). Readiness for organizational change scale: Validity and reliability study. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 25(4), 663-692. doi:10.14527/kuey.2019.016

- Carpenter, N.C., & Berry, C.M. (2017). Are counterproductive work behavior and withdrawal empirically distinct? A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Management, 43(3), 834-863.

- https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314544743

- Cassese, E.C., Farhart, C.E., & Miller, J.M. (2020). Gender differences in COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs. Politics & Gender, 16(4), 1009-1018. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1743923x20000409

- Craft, S., Ashley, S., & Maksl, A. (2017). News media literacy and conspiracy theory endorsement. Communication and the Public, 2(4), 388-401. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047317725539

- Douglas, K.M., & Leite, A.C. (2017). Suspicion in the workplace: Organizational conspiracy theories and work related outcomes. British Journal of Psychology, 108(3), 486-506. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12212

- Douglas, K.M., & Sutton, R.M. (2018). Why conspiracy theories matter: A social psychological analysis. European Review of Social Psychology, 29(1), 256-298. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2018.1537428

- Dr. Anasica, S., Sweta, B. (2020). Analysing the factors involved in risk management in a business. International Journal of New Practices in Management and Engineering, 9(03), 05 - 10.

- https://doi.org/10.17762/ijnpme.v9i03.89

- Falkenburg, K., & Schyns, B. (2007). Work satisfaction, organizational commitment, and withdrawal behaviours. Management Research News. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170710823430

- Federico, C.M., Williams, A.L., & Vitriol, J.A. (2018). The role of system identity threat in conspiracy theory endorsement. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(7), 927-938. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2495

- Gavin, R.S., Reisdorfer, E., Zanetti, A.C.G., & da Silva Gherardi-Donato, E.C. (2017). Relationships between anxiety and depression in the workplace: Epidemiological study among workers in a public university. Cadernos Brasileiros de Saúde Mental/Brazilian Journal of Mental Health, 9(23), 24-38.

- Gerts, D., Shelley, C.D., Parikh, N., Pitts, T., Ross, C.W., Fairchild, G., . . . & Daughton, A.R. (2021). “Thought I’d share first” and other conspiracy theory tweets from the covid-19 infodemic: Exploratory study. JMIR public health and surveillance, 7(4), e26527. https://doi.org/10.2196/preprints.26527

- Green, R., & Douglas, K.M. (2018). Anxious attachment and belief in conspiracy theories. Personality and Individual Differences, 125, 30-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.023

- Hair Jr, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): Sage publications. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.002

- Hair Jr, J.F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V.G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European business review. https://doi.org/10.1108/ebr-10-2013-0128

- Hair, J.F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M., & Mena, J.A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 40(3), 414-433. https://doi:10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6.

- Hameedi, K.S., Al-Fatlawi, Q.A., Ali, M.N., & Almagtome, A.H. (2021). Financial performance reporting, IFRS implementation, and accounting information: Evidence from Iraqi banking sector. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 8(3), 1083-1094. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijabim.20210101.oa2

- Kanungo, R.N., & Mendonca, M. (2002). Employee withdrawal behavior. In Voluntary employee withdrawal and inattendance (pp. 71-94). Springer, Boston, MA.. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0599-0_4

- Kbelah, S., Almusawi, E., & Almagtome, A. (2019). Using resource consumption accounting for improving the competitive advantage in textile industry. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 14(2), 275-382. https://doi.org/10.36478/jeasci.2019.575.582

- Macovei, C.M. (2016). Measuring job anxiety in military organization. In International Conference Knowledge-based Organization, 22(2), 451-456. Sciendo. https://doi.org/10.1515/kbo-2016-0077

- Mannor, M.J., Wowak, A.J., Bartkus, V.O., & Gomez, M.L.R. (2016). Heavy lies the crown? How job anxiety affects top executive decision making in gain and loss contexts. Strategic Management Journal, 37(9), 1968-1989. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2425

- Miller, J.M. (2020). Do COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs form a monological belief system? Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique, 53(2), 319-326. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0008423920000517

- Muschalla, B. (2009). Workplace phobia. German journal of psychiatry, 12(1), 45-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500903207398

- Nguyen, A.D. (2018). Perceived overqualification and withdrawal among seasonal workers: Would work motivation make a difference? https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6240

- Quinones, A.I. (2002). Effects of goal congruence on withdrawal behavior, as mediated by organizational commitment. Theses Digitization Project, 2243. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2243

- Roukis, G.S. (2006). Globalization, organizational opaqueness and conspiracy. Journal of Management Development, 25, (10), 970–980. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710610708595

- Rurkkhum, S. (2018). The impact of person-organization fit and leader-member exchange on withdrawal behaviors in Thailand. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 10(2). DOI: 10.1108/APJBA-07-2017-0071

- Su, Y., Lee, D.K.L., Xiao, X., Li, W., & Shu, W. (2021). Who endorses conspiracy theories? A moderated mediation model of Chinese and international social media use, media skepticism, need for cognition, and COVID-19 conspiracy theory endorsement in China. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, 106760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106760

- Sullivan, D., Landau, M.J., & Rothschild, Z.K. (2010). An existential function of enemyship: Evidence that people attribute influence to personal and political enemies to compensate for threats to control. Journal of personality and social psychology, 98(3), 434. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017457

- Sunil, K., & Rooprai, K. (2009). Role of emotional intelligence in managing stress and anxiety at workplace. Proceedings of ASBBS, 16(1), 163-172. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315290812-20

- Tangherlini, T.R., Shahsavari, S., Shahbazi, B., Ebrahimzadeh, E., & Roychowdhury, V. (2020). An automated pipeline for the discovery of conspiracy and conspiracy theory narrative frameworks: Bridgegate, pizzagate and storytelling on the web. PloS one, 15(6), e0233879. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233879

- van Prooijen, J.W., & Acker, M. (2015). The influence of control on belief in conspiracy theories: Conceptual and applied extensions. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29(5), 753-761. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3161

- Van Prooijen, J.W., & Jostmann, N.B. (2013). Belief in conspiracy theories: The influence of uncertainty and perceived morality. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(1), 109-115. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1922

- van Prooijen, J.W., & de Vries, R.E. (2016). Organizational conspiracy beliefs: Implications for leadership styles and employee outcomes. Journal of business and psychology, 31(4), 479-491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9428-3

- Van Prooijen, J.W., & van Dijk, E. (2014). When consequence size predicts belief in conspiracy theories: The moderating role of perspective taking. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 63-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.06.006

- Vignoli, M., Muschalla, B., & Mariani, M.G. (2017). Workplace phobic anxiety as a mental health phenomenon in the job demands-resources model. BioMed research international, https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3285092

- Whitson, J.A., & Galinsky, A.D. (2008). Lacking control increases illusory pattern perception. science, 322(5898), 115-117. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1159845