Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6

Strategic Aspects of the Development of Catching Up Countries: Structural Approach

Guldariya Aimagambetova, Karaganda Economic University of Kazpotrebsoyuz

Lyazat Talimova, Karaganda Economic University of Kazpotrebsoyuz

Baldyrgan Jazykbayeva, Karaganda Economic University of Kazpotrebsoyuz

Citation Information: Aimagambetova, G., Talimova, L., & Jazykbayeva, B. (2021). Strategic aspects of the development of catching up countries: structural approach. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 20(6), 1-9.

Abstract

The economies of catching up countries have always been under the pressure of globalization. This is the consequence of the situation when, being in a subordinate position of “Center-Periphery”, developing countries use comparative advantages in international trade, specializing in the supply of products from low-tech industries. This leads to structural shifts that do not always correspond to an efficient economy. The economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan is in this situation. In the article, the authors tried to assess the structural changes that occurred in Kazakhstan in the period from 1990 to 2019. Since the beginning of independence, Kazakhstan has been actively involved in international trade, opened its market for foreign investment, and export-import operations were implemented almost without restrictions. The result was significant structural shifts that resulted in the deindustrialization of the economy. The impact of globalization on the catching-up economies has received much attention in the works of many economists. There are a lot of studies that are devoted to issues of catching-up development, problems of redistribution of labor from less productive, labor-surplus sectors of the national economy to capital-intensive and more productive sectors.

Keywords

Strategy, Development, Globalization, Economy, Economic Growth.

Introduction

The impact of globalization on the catching-up economies has received much attention in the works of many economists. There are a lot of studies that are devoted to issues of catching-up development, problems of redistribution of labor from less productive, labor-surplus sectors of the national economy to capital-intensive and more productive sectors. Development strategies should reflect the specific development needs and conditions of countries. In developing countries, which have made more significant progress in integrating into the world economy, rapid and sustainable economic growth has been stimulated by the reorientation of the structure of the economy from the primary sector to the manufacturing and services sector, accompanied by a gradual increase in labor productivity. This process of structural change has been driven by rapid, efficient and sustainable capital accumulation in the context of a coherent development strategy.

Some economic research in this area has focused on the problems of getting benefits from globalization, changing the structure of the economy, and the place of catching-up countries in the global value chain (McMillan et al., 2014). Research shows that not all countries have the same benefits of participating in globalization. Generally, countries with stronger economies that are at the center of economic processes can benefit from participation and have more opportunities to improve the quality of the economic structure (Diao & McMillan, 2018). A special place in the research is occupied by the problems of the influence of foreign direct investment as agents of structural changes in different regions (Elekes et al., 2019). The research also concludes that the distribution of benefits from globalization is uneven. Some economists have conducted research to identify cause-and-effect relationships between structural and institutional changes in countries with different levels of development and tried to assess the extent to which these changes affect the economies of developed and developing countries (Soyyigit, 2019). In General, it should be noted that all these studies were conducted with the countries of Europe, Asia, and Africa, but the impact of globalization on the structural transformation of the economy of Kazakhstan was not often assessed. In 1991 Kazakhstan became independent.

Literature Review

The first theories related to the assessment of the economic structure were proposed by Adam Smith, who argued that the source of Wealth of Nations lays in the aggregate labor of different professions, thanks to the division of labor, labor efficiency increases and the welfare of the people increases. In his studies, in which he investigated the causes of the Wealth of Nations, he argued that the first condition and source of national wealth is agriculture, then production, and finally – trade and services. This was the first idea of a certain structure of the economy and the need to maintain proportions (Smith, 1976).

In the research of Ricardo, we can also see the idea of the need to observe structural proportions in the economy. In his research on the value of the product, wages, and land rents, he formed judgments about the impact of productivity on the formation of the exchange value of goods, as well as the features of obtaining differential land rents. It was important to believe that due to the inequality of profits on invested capital, capital moves from one industry to another, which is the first explanation for structural shifts. Special attention in the theories was paid to the foreign trade in the specialization of countries and the peculiarities of the economic structure (Cardinale & Scazzieri, 2019).

Later, structural transformations were considered in the works of such classics of economic theory as Karl Marx and Tugan-Baranovsky, but more interest in the study of economic growth is occupied by the works of researchers who dealt with the economic development of catching-up countries.

Arthur Lewis continued the study of economic growth in the tradition of A. Smith and D. Ricardo and proposed his concept of economic growth in developing countries. In his research, he considered the dual nature of the economic system of developing countries. There was a labor-surplus agricultural sector with a low level of labor productivity and a manufacturing sector with fewer employees and high productivity indicators (Kattel et al., 2011).

Nurkse (2011) justified the “Big Push Model” theory by saying that the conditions of reproduction in developing countries are locked in a “Vicious Circle of Poverty”. He argued that countries have a low ability to save due to low real income. Low real income is a consequence of low labor productivity, which, in turn, is determined by a lack of capital.

Methodology and Analysis

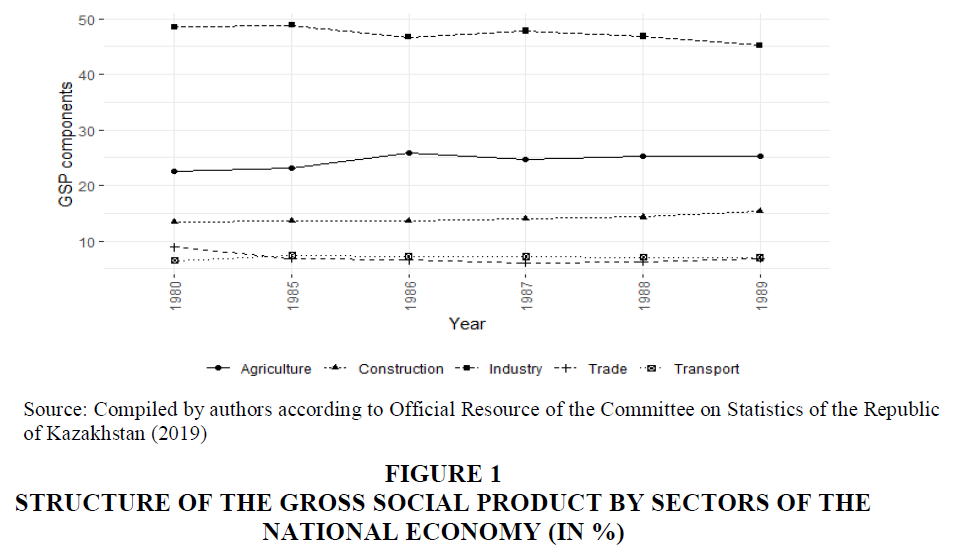

At the end of the 1980s, the last decade of Kazakhstan's membership in the Soviet Union, the structure of the economy was presented as follows (Figure 1). A large share in the GDP structure was represented by industry, and only after that agriculture, a relatively large share was occupied by other industries. If we consider the structure of employment during this period, it was also represented by high employment values for industries. This significantly distinguishes the economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan from the traditional economies of Asia and Latin America, which were the subject of economic development theories.

At the end of the 1980s, the last decade of Kazakhstan's membership in the Soviet Union, the structure of the economy was presented as follows in Figure 1.

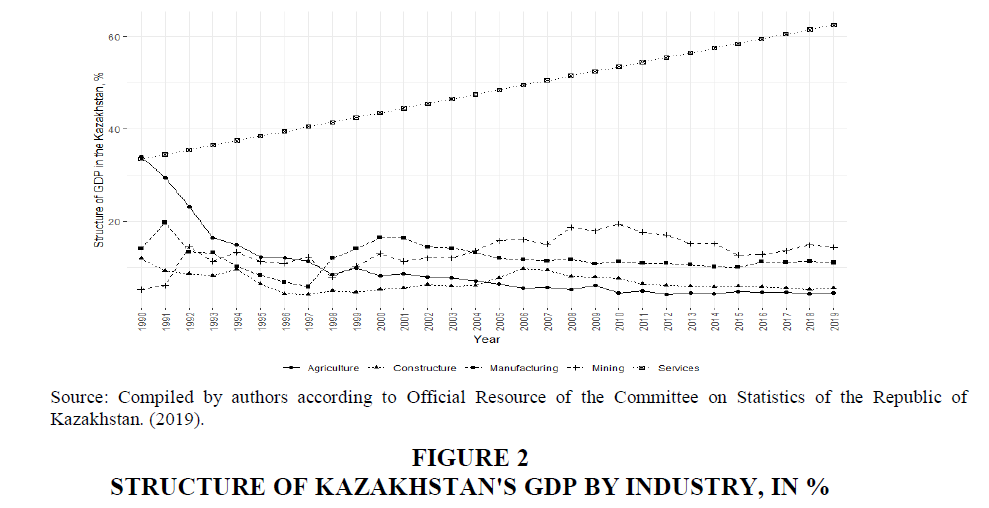

The ratio of industry shares changed significantly in the following decades, when there was a rapid decline in the share of agriculture, a large decline in the share of manufacturing (Figure 2).

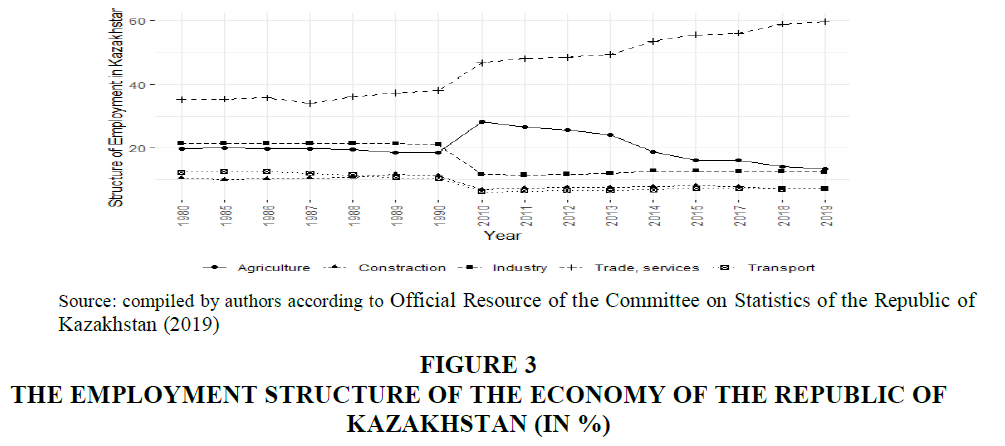

The structure of employment in the sectors of the economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan during the Soviet period showed almost the same share of people employed in the economy, both in agriculture and in industry. Services, trade (including education and public administration) were predominant. During the period of independence, the structure of employment has undergone significant changes (Figure 3).

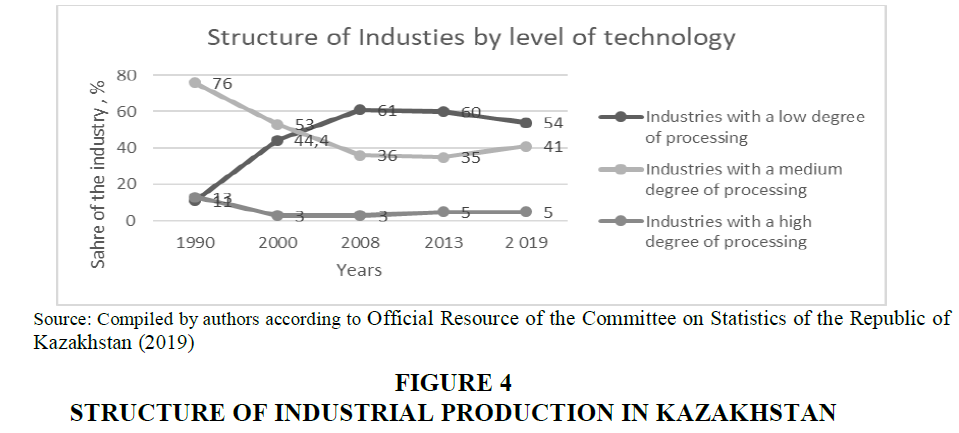

The results of the analysis (Figure 4) show the process of increasing the share of low-tech industries in the total volume of industry, which indicates a decrease in the technological complexity of production and manufactured products.

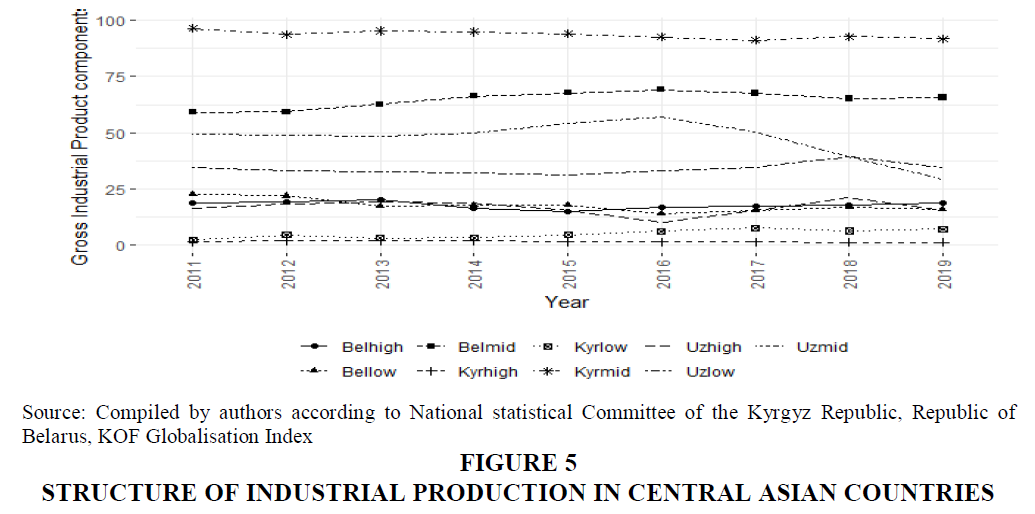

For example, in the countries that were part of the Soviet Union, such as Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Belarus, today there is a different structure of industrial production, in which there is no clear excess of industries with low productivity (Figure 5).

Belhigh – share of the Industries with high degree of processing in Belarus, Belmid - share of the Industries with middle degree of processing in Belarus, Bellow - share of the Industries with low degree of processing in Belarus, Kyrhigh - share of the Industries with high degree of processing in Kyrgystan, Kyrmid - share of the Industries with middle degree of processing in Kyrgystan, Kyrlow – share of the Industries with low degree of processing in Kyrgystan, Uzhigh – share of the Industries with high degree of processing in Uzbekistan, Uzmid – share of the Industries with middle degree of processing in Uzbekistan, Uzlow - share of the Industries with low degree of processing in Uzbekistan.

Discussion

Kazakhstan, being a country with a “small economy”, is trying to realize its comparative advantages in the world market. The results of such relations, examples of developing countries have already been studied by many researchers. Globalization offers many advantages through the openness of markets, the relative absence of barriers, foreign direct investment flows, the freedom of movement of labor, and the transfer of technology, as well as many opportunities for positive externalities. Considering the structure of industrial production, we tried to systematize the industry on the principle of technological complexity of the organization of production, similar to the authors who conducted such an analysis. The main points of the analysis show the process of increasing the share of low-tech industries in the total volume of industry, which indicates a decrease in the technological complexity of production and manufactured products. Kazakhstan met with the process of deindustrialization – a consequence of the “Dutch disease”. Corden (1981) in his writings describes this process, when the development of the one “rapidly developing exporting industry” leads to a reduction in other industries, usually related to manufacturing. Kazakhstan is using its comparative advantage by Ricardo (1817) and country has been actively involved in the international division of labor. Kazakhstan's specialization was the export of raw materials, and the flow of foreign investment was mainly directed to the development of these industries. The profitability of the raw materials sector increased, investment in the oil and mining industry increased, and technologies for extracting raw energy resources were relatively modernized. This has led to the growth in labor productivity in industries.

Application Functionality and Results

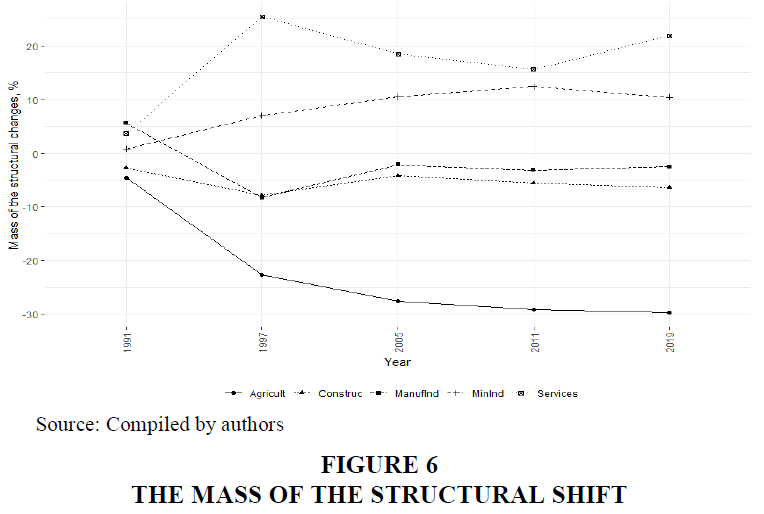

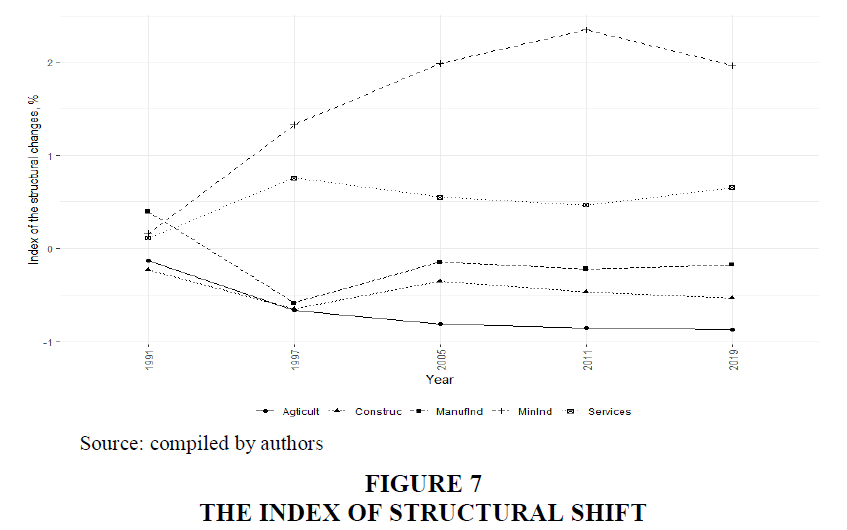

The described indicators allow us to assess the qualitative changes between the elements of the economic structure. In dynamics, these indicators show the intensity of the structural shifts of the economy were over a certain period of time, and also allow us to assess the economic interests aimed at meeting the material and non-material needs of various economic agents (Ranis, 2014). We calculated the values of the structural shift mass and the structural shift index in relation to the Kazakh economy. The results are shown in Figures 6 &7.

A similar situation is observed in the structural shift index (Figure 7), but we see that when measure structural shifts using the index method, the rate of structural shifts in the mining industry is much higher than in the service sector.

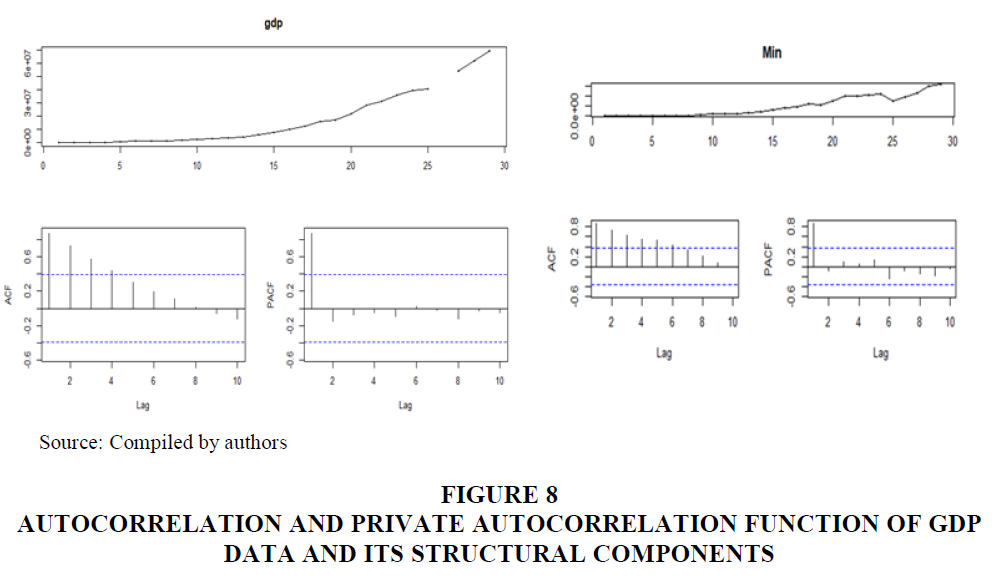

In our article, we tried to assess the impact of each sector of the economy on the resulting GDP. In particular, how much the size of GDP will change depending on the contribution of mining, manufacturing, agriculture and the service sector. Analysis of the behavior of autocorrelation (ACF) and partial autocorrelation (PACF) (Figure 8) showed that the analyzed time series are non-stationary. However, by constructing first-order differences and following the behavior of autocorrelation (ACF) and partial autocorrelation (PACF) we can no longer speak so clearly about the non-stationarity of our time series.

Figure 8 Autocorrelation and Private Autocorrelation Function of Gdp Data and its Structural Components

The Dickey-Fuller tests more clearly reject the null hypothesis of stationarity of the analyzed time series (Table 1).

| Table 1 Dickey-Fuller Test for Stationarity | |

| Sector | Augmented Dickey-Fuller Test |

| Mining | Dickey-Fuller=-1.853, Lag order=3, p-value=0.629 alternative hypothesis: stationary |

| Manufacturing | Dickey-Fuller=1.8757, Lag order=3, p-value=0.99 alternative hypothesis: stationary |

| Agriculture | Dickey-Fuller=0.42901, Lag order=3, p-value=0.99 alternative hypothesis: stationary |

| Construction | Dickey-Fuller=-0.65228, Lag order=3, p-value=0.9631 alternative hypothesis: stationary |

| Services | Dickey-Fuller=1.4351, Lag order=3, p-value=0.99 alternative hypothesis: stationary |

The non-stationary nature of time series does not allow us to offer a standard model. We tried to analyse the contribution of main sectors of economy to GDP based on data from the Republic of Kazakhstan GDP growth indices in the period from 1990 to 2019.

With the decline in manufacturing output, there was an increase in imported goods of high and medium processing. Imports replaced the shrinking share of manufacturing. In connection with the growth of incomes for the population and the state from economic rents received from “rapidly developing industries”, the share of the “non-tradable” sector, which includes construction trade, services, that is, economic activities that cannot be exported, sharply increased. This explains the growth in the share of these industries in the total gross domestic product, as well as structural changes in employment. There is also a shift of labor from agriculture and industry to the service sector. And here we cannot say that these changes are related to the transformation of the industrial stage into the post-industrial one. The value added created in the service sector is not much higher than for the industrial sector.

Conclusion

As a result, we see that the largest contribution to GDP growth in Kazakhstan in the period from 1990 to 2019 was provided by growth in the mining industry and the service sector. At the beginning of its independent development, the economy of Kazakhstan did not correspond to the characteristics of the country described in the theories of R. Nurkse, P. Rosenstein-Rodan, G. Singer and R. Prebisch. The entire period of development has only worsened the gap in the country's technical, technological and economic development from the developed countries of the modern world.

The regression analysis carried out in the research showed that the largest contribution to GDP growth was made by the growth of the mining industry and the growth of the service sector. Which once again proves that Kazakhstan demonstrates an ineffective policy of participation in international trade.

Thus, several main areas of modernization can be identified, which have already proven their effectiveness in countries that have passed the way of catching up development. It:

- Determination of priority areas of technological development, reasonable borrowing of new technologies;

- Increase in the accumulation rate as one of the main conditions for modernization;

- Improvement of foreign trade policy and customs and tariff regulation in order to create conditions for industrial growth. Stimulation growth of new industries, their temporary protection in the fight against imports.

References

- Cardinale, I., & Scazzieri, R. (2019). Explaining structural change: actions and transformations. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 11(51), 393-404.

- Corden, V.M. (1981). The exchange rate, monetary policy and North Sea oil. Oxford Economic Paper, 11(33), 23-46.

- Diao, X., & McMillan, M. (2018). Toward an understanding of economic growth in Africa: A reinterpretation of the lewis model. World Development, 14(109), 511-522.

- Elekes, Z., Boschma, R., & Lengyel, B. (2019). Foreign-owned firms as agents of structural change in regions. Regional Studies, 11(53), 159-167.

- Kattel, R., Kregel, J.A., Reinert, E.S., & Nurkse, R. (2011). Classical development economics and its relevance for today, Anthem Press. 364p.

- McMillan, M., Rodrik, D., & Verduzco-Gallo, I. (2014). Globalization, structural change, and productivity growth, with an update on Africa. World Development, 11(63), 11-32,

- Official Resource of the Committee on Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2019). Retrieved from www.stat.gov.kz

- Ranis, G. (2014). Arthur Lewis’s contribution to development thinking and policy. The Manchester School, 6(72), 712-723.

- Ricardo, D. (1817), On the principles of political economy and taxation (1 ed.), London: John Murray.

- Smith, A. (1976). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 334p.

- Soyyigit, S. (2019). A comparative analysis of causality between institutional structure and economic performance for developed and developing countries. Montenegrin Journal of Economics, 3(15), 37-51.