Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 5

The Consequence of the Decision of the Constitutional Court in Forestry on the Recognition of Traditional Forests in Indonesia

Lego Karjoko, Sebelas Maret University

I Gusti Ayu Ketut Rachmi Handayani, Sebelas Maret University

Albertus Sentot Sudarwanto, Sebelas Maret University

Djoko Wahju Winarno, Sebelas Maret University

Abdul Kadir Jaelani, Sebelas Maret University

Willy Naresta Hanum, Sebelas Maret University

Abstract

The existence of indigenous peoples has long been marginalized under state control. All of this ended with the Constitutional Court Decision Number 35/2012, which stated that customary forests are in the traditional territory and not in state forest areas. This study aims to analyze the impact of the Constitutional Court decision on forestry forest change and the risks of the Constitutional Court decision on strengthening indigenous forestry peoples' rights. The results showed that the disadvantage of the Constitutional Court decision against indigenous peoples was the recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples to their customary forests. However, this recognition requires the existence of a regional regulation stipulating customary law communities and their traditional territories, which have not yet been formed in Riau or Papua. At the empirical level, the Constitutional Court decision can also have negative implications, which the government strives to prevent and prevent.

Keywords

Constitutional Court; Forestry; Law.

Introduction

Changes in forestry law in Indonesia are quite significant, considering the number of Constitutional Court decisions on Forestry. The law that regulates forestry is Law Number 41 of 1999 concerning Forestry. From a process perspective, the Forestry Law is far from being a participatory and transparent process. This law was only briefly discussed, namely for 18 days of effectiveness by the House of Representatives for the transitional period of 1997-1999. UU no. 41 of 1999 does not make corrections to the thinking background that Law no. 5 of 1967. Meanwhile, from the formal aspect, the process's defects were deemed to have occurred from the design stage to the discussion of the Forestry Bill material in the DPR (Ruman, 2012)

As a result, Forests often become an arena of conflict (conflict) between various interested parties. Forest Zone Tenure Conflicts are multiple disputes or disagreement over claims over control, management, utilization, and use of forest areas. Tenure conflicts often involve various parties, ranging from local to a national scale, even international scale. Forest tenure conflicts occur in almost all regions of Indonesia. The issue of forestry conflicts is not a problem of the existence of large companies as HGU subjects, but rather a question of the incoherence of laws and regulations governing plantations. According to Fuller's opinion, the failure of the forestry legal system to create just and prosperous forestry businesses, and at the same time can break the chain of forestry conflicts is caused by the failure to use the principle of the social function of the right to cultivate (HGU) as a guide in drafting laws and regulations in the field of Forestry HGU (Karjoko et al., 2020)

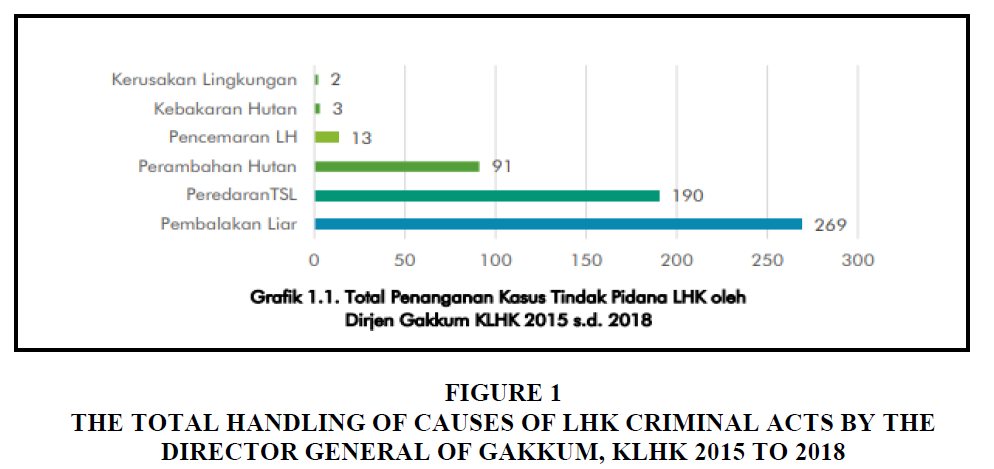

The increase in the number of tenurial conflicts in forest areas is also exacerbated by the low quality of laws and regulations in the forestry sector, thus opening up loopholes in cases of trade-in protected wild plants and animals. To date, wildlife crime cases are in the second rank of all environmental and forestry criminal cases handled up to P.21 by the Directorate General of Law Enforcement (Dirjen Gakkum) of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in the 2015 to 2018 period, namely as illustrated in the Figure 1 below: (Jatmiko et al., 2019).

Figure 1 The Total Handling of Causes of LHK Criminal Acts by the Director General of Gakkum, Klhk 2015 to 2018

This Figure 1 shows that forests are a source of conflict because many parties are interested in managing them, both interpersonal wars and disputes with state institutions or companies. Some of the conflicts that occur in forest management are conflicts over tenure (tenure). Forest land tenure refers to who owns the forest land, and who uses, manages, and decides forest resources. Forest land tenure determines who is allowed to use what resources, in what ways, for how long and under what conditions, and who has the right to transfer to other parties and how. As a result, crimes against protected animals have also experienced these problems; this can be seen in the 150 decisions on crimes against rescued animals from 2009 to October 2019 due to tenurial conflicts. Of the 150 decisions for the period 2009 up to. In October 2019, the highest number of judgments on crimes against protected animals came from 2014 with 40 findings. In 2013, as many as 28 decisions, and in 2018 as many as 20 decisions. Meanwhile, the fewest verdicts in cases of crimes against protected animals came from 1 decision in 2009, 7 in 2010, and 6 in 2017 (ignoring the number of decisions in 2019 as many as four decisions, due to limited investigation until October 2019).

Apart from the issue of tenurial conflicts over forest areas, the Constitutional Court has several times reviewed Law no. 41 of 1999. It was recorded that there were 117 Petitioners with various professions who tested the Law. Amendments to the Forestry Law are quite significant if you look at the number of Constitutional Court decisions on Forestry. Of the eight decisions of the Constitutional Court in the review of Law no. 41 of 1999, four were granted, three were rejected, and one case could not be accepted. Also, one point has been registered with the Constitutional Court, but the petitioner withdrew it. Of the eight decisions, four decisions have relevance to forest tenure reform, namely: Decision on Case No. 45 / PUU-IX / 2011 relating to the Constitutionality of defining forest areas, Case Decision No.34 / PUU-IX/ 2011 regarding the limits of forest control by the state on rights over land that are used as forest areas, case decision No.35 / PUU -X / 2012 regarding the Constitutionality of customary forests and conditional recognition of the existence of ordinary law communities and the Decision on Case No. 95 / PUU-XII / 2014 regarding the Constitutionality of the meaning of forest destruction.

The legislators have not followed up most of the decisions of the Constitutional Court. Epistemologically, this problem becomes fascinating because the Constitutional Court decision is final and binding, but only on paper, but there is no guarantee and mechanism to be implemented. According to Fajar Laksono Suroso, this problem is clearly illustrated in the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, which demonstrates an imbalance in the relationship between the Constitutional Court and the DPR, DPD, and the President as legislators. Even the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia and the Law on the Constitutional Court does not contain regulations on how the Constitutional Court decisions are implemented; the two rules only include a statement that the Constitutional Court has the authority to judge at the first and last levels whose decisions are final and have legal force since they have been pronounced in a plenary session open to the public. However, Article 59 paragraph (2) of Law Number 8 the Year 2011 concerning the Constitutional Court states that the DPR and the President will only follow up on the Constitutional Court decisions if necessary (Jaelani et al., 2019)

These actions have resulted in the loss of peace, livelihoods, and even the lives of community members involved in the conflict. Forest tenure conflicts also do not provide business certainty for license holders and interfere with government performance. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry is currently running a program to accelerate the resolution of forest tenure conflicts. The objectives, among others, are to create forest areas with legal certainty and justice. Bringing back the state to protect the entire nation and provide a sense of security to all citizens, through free and active foreign policy, trusted national security, and the development of an integrated Tri Matra national defense based on national interests is the main Nawa Cita list of the nine agendas proclaimed by the President. The implementation of the Constitutional Court Decision and strengthening the Directorate for Management of Tenurial Conflicts and Customary Forests is one that is urgent to do, considering the target of handling tenurial conflicts with a target of 12.7 million hectares for five years (Sudrajat, 2019).

The Consequence of the Decision of the Constitutional Court on the Amendment of the Forestry Law

The Constitutional Court decision No. 35 / PUU-X/2012 extends the tradition of the state recognition and protection of the rights of orthodox groups to forests. The Constitutional Court Decision number 35 / PUU-X/2012 can, however, also give rise to negative consequences from the results of the research. Decision No. 35 / PUU-X/2012 of the Constitutional Court may cause a dispute between customary law communities and business entities using their traditional forests, such as planting companies. Conflict arises because the customary law of the community feels justification for requesting that the plantation company return or pay any money in return or substitute use of the custom area of jurisdiction (Kadir et al., 2019)

At the practical level, customary law demands from society emerge not only after the Constitutional Court Decision No. 35 / PUU-X/2012, but before the Constitutional Court Decision No. 35 / PUU-X/2012 occurred. These demands typically arise because plantation companies do not socialize and communicate their efforts to the customary law of the community when starting a company, no request for permission from the traditional law community, no pay money grows as compensation from the usual forest area that they cultivate or have not kept their commitments to customary law of the society , for example, the commitment to build plants Even these demands could have emerged despite the money changing growth provided because residents are customary law families or elder descendants who believe they have not earned it (Jaelani et al., 2019)

It is not unusual for the legal community to sue adat ends in dispute if the plantation companies have not been fulfilled. Corporate reasons the plantation refuses the demands of the legal community adat is an area which is attempted to enter within the authorization (concession) given to it and indigenous peoples can not provide formal legal proof that the site is included in their traditional territory. As an example of a dispute in Riau is a dispute between state-owned plantation companies (PTPN V) in Kampar-Riau district with customary law communities. In Papua, by comparison, an example is a dispute between PTPN II (a palm oil plantation company) and indigenous peoples in Keerom District-Papua, and PT rivalry. With traditional society there is Sinar Mas (plantation com any). This is the local rule by which societies of customary law are decided, followed by a map of their traditional territories considered necessary to be able to prove an established indigenous peoples (Hanadi, 2019).

Another negative issue that occurred with the Constitutional Court Decision No. 35 / PUU-X/2012 is customary land where customary forest-grown land sold to third parties to insist on the necessities of existence, particularly if you see the economic conditions of indigenous peoples , especially in Papua, which are relatively minimal. Customary land for sale is a common land area that is handed over to a member of the established community of law to be controlled and managed to fulfill life needs. Traditional land sales are carried out without understanding the traditional leader or permission from other members of the customary law community, so this may create a dispute between the buyer and the indigenous peoples who do not know about the purchase sales referred to. In addition to economic factors, the buying and sale of ulayat land may occur due to the persuasion of investors to the traditional elders to sell ulayat land, particularly if the investor is in trouble obtaining a regional license from the local government area to conduct business. However, both in Riau Province and in Papua, there is an ulayat land certificate of sale and purchase until such time as this research was carried out yet by any group. Even as an attempt to prevent the selling of ulayat land, a community of customary law in Kampar, District-Riau has sent a letter to the Kampar District Land Office for not allowing or preventing it if there are parties that sell or buy the customary land referred to (Arrsa, 2014).

The Constitutional Court Decision No. 35 / PUU-X/2012 also feared that it could cause damage to traditional forests, thereby preventing the protection of typical forests. Indigenous forest damage caused by customary law group will occur through illegal felling of tree, sale of forest wood, turning the forest into land farming, etc. However, as Yance Tandong puts it, there's no need to worry. Deforestation, for the most part, is caused by large corporations cutting trees in the forest which are ideal for opening plantations that involve a relatively large area due to illegal logging (Kadir et al., 2020).

Like Yance Tandong, Masriadi has said that harm to the forest caused in the area by customary law has never happened so far. Customary law societies typically have the knowledge to conserve the traditional forest of biodiversity, as customary forests are an important feature to them. Legal society citizen adat also fears being carelessly cutting trees in customary forests because they believe the sacred importance of customary forests. They 're scared of disaster, if you cut it down. There is also a law that obeys and enforces customs well, to ensure the protection of the regular forest. For example, Masriadi also had the Kampar regency Rubio forest, Riau, whose sustainability was sustained until recently. Kalpataru awarded him as a token of appreciation country that has succeeded in maintaining the customary Rumbio forest. In customary law, cutting trees can only be done to meet ends, and there are not too many of them, for example, to create customary law houses for community members with a minimum economic level. The tree felling was carried out after the customary leader received permission. Offense against the rules of the traditional law is subject to the price of the tree which he cuts fine times. Money fines go to the ordinary treasury and are used for public gain and welfare, for example, to support traditional activities, to compensate the families of the members of the customary law community who died country, to create common means, etc. Generally speaking, indigenous peoples that only use forest items, such as gathering fallen wood or twigs for firewood, taking rattan for crafts, catching river fish, etc (Leonard et al., 2020).

Decision No. 35 / PUU-X/2012 of the Constitutional Court also gives rise to a dual law governing customary forests, namely national law (Law No. 41/1999) and customary law. If customary law is consistent with national law, this dualism won't cause problems. Problems arise when customary law is incompatible with national law, because it poses a problem, namely which law will be implemented. For eg, tree cutting in law customs is subject to a fine of 10 times the price of trees being cut, while provisions logging trees without the permits provided for in Article 50 paragraph (3) letter e of Law Number 41 In 1999, in Article 78(5) of Law No 41/1999, he was punished with a maximum imprisonment of 10 ( ten) years and a fine of IDR 5,000,000,000 (five bil).

On the practical level, in the case of dualism, such laws are implemented by authorities, which is allowed by national law. Moreover, there is no perda stipulating customary law communities (including customary forests) which proves that the forest in question is a customary forest which, in reality, also applies customary law in the regular forest areas. The enactment of national law is increasingly fading and less recognized by generations of young successors of customary law communities , especially customary law in its unwritten form. Traditional leaders, including traditional leaders in the Kenegerian Kuntu Kampar-Riau Regency, would also attempt to enforce customary regulations so that they can easily be passed on to future generations. Customary regulations on forbidden forests are one of the customary regulations which have been passed.

According to Arizona (2013), among the Land Parcels and Other Natural Resources Law, Law No. 41 of 1999 on Forestry (Forestry Law), most frequently reviewed before the Constitutional Court, was rejected twice, with positions granted three times, and rejected twice. This suggests that the Forestry Law still includes a number of procedural problems, which is because it was enacted before four revisions to the 1945 Constitution (1999-2002) were adopted at the time it was established (1999). So it's no wonder there's a lot of material from the Forestry Law that is not in line with the new constitution after the amendments. Impact amar of the Constitutional Court's ruling on forest law amendments.

Constitutional Court Decision No. 35/2012 This is a mistake against an agricultural strategy followed by the forestry and chronic ministry and part of the forester's official information and habitus. Rachman 's opinion is not entirely accurate because Magdalena (2013) claims that MHA or its members in HPH and SK areas have given a biased policy of customary forest management through the Minister of Forestry Decree No. 251 / KPTS-II/1993 on Determination of Forest Product Selection by MHA or its members in HPH and SK areas Minister of Forests No. SE.75/Menhut-II/2004 on Indigenous Peoples' Customary Law Issues and Compensation Claims.

Decisions of the Constitutional Court that include categories of customary forests being part of the private forest means refusing the applicant 's proposal categorizes customary forests into various specific forest state and forest rights. This is inconsistent with the definition of the decision of the Constitutional Court, which claims in the Forestry Case, too. Three legal subjects have natural relationships with forests, namely forest holders of state, MHA, and land rights. The legal relationship over the forest in this case is attached to the legal relationship over property, so it can not be differentiated between land and forest rights. There is state forest on state property, on ulayat ground, their customary forest, and private forest on property with title rights (Soediro et al., 2020)

The Consequence of the Decision of the Constitutional Court on Forestry Strengthening Indigenous Peoples' Rights

The Constitutional Court Decision Number 35/PUU-X/2012 is a verdict that is expected to provide all the protection to indigenous peoples on indigenous peoples' rights, both rights in forestry, and position indigenous peoples as objects and legal subjects. In addition, it is believed that the Constitutional Court Decision No. 35/PUU-X/2012 may have negative consequences as the Constitutional Court Decision No. 35/PUU-X/2012 is a conditional judgment on the classification of a customary forest only if it is still understood that the recognition of common law communities by familiar law communities is real (Putri et al., 2019).

After 5 (five) years, the decision of the Constitutional Court Number 35/PUU-X/2012, there are still many cases of criminalization of the legal community, the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN) noted in 2015, two years after the Constitutional Court decision Number 35/PUU-X/2012 there was 24 cases criminalization. Based on several criminalization cases of the legal community customs that occur, some instances are proceeded to court to be then decided by the court (Jaelani et al., 2020).

Constitutional Court decisions are final and binding as contained in Article 10 paragraph (1) of Law Number 24, the Year 2003 concerning the Constitutional Court, is final, means a verdict The Constitutional Court cannot appeal, appeal, or review back. Climbing implies the Constitutional Court's decision not only applies to the parties but also applies to the whole society. Indonesia is no exception for judges as law enforcement officers. In terms of this, the judge handles cases related to indigenous peoples' recognition as the right holder to use the Constitutional Court Decision Number 35 / PUU-X / 2012 as a guideline for realizing protection to the customary law community.

Criminalization of indigenous peoples in Maninjau, Agam District with Case Number 129 /Pid.B/LH/2017/PN.Lbb constituting one case where 2 (two) people were arrested for cutting trees in his customary land, which is used for daily needs, in which the communal land area is confirmed as a Forest Zone Nature preserve. According to the Padang Legal Aid Institute (LBH Padang), which assisted two people in the Maninjau case, the judge did not know the forestry polemic in Indonesia. Namely, the judge did not see the difference between designation and forest gazettement. 76 Forest gazettement is not the last process of the forest area; there are other processes to be designated as a forest area. In the Verdict. The Constitutional Court Number 95 / PUU-XII / 2014 stated that indigenous peoples residing in and around forest areas justified to take advantage of daily forest products and not for commercial purposes. However, in this case, the judge was, in fact did not consider the decision of the Constitutional Court Number 95/PUU-XII/2014 (Hanadi, 2019).

During the trial process, LBH provided advice to the assembly to carry out Local Checks (PS) to know the status and the existence of a case incident to find material truth. However, there is no trial agenda for local inspection in the criminal justice process, so that the list was not implemented. Other Constitutional Court decisions that are used to rely on The defense by LBH is the Decision of the Constitutional Court Number 35/PUU-X/2012 concerning the exclusion of customary forests from the forest. Country. The panel of judges also did not consider the verdict. Lubuk Basung District Court Judges in deciding cases, by punishing each of the defendants with imprisonment 7 (seven) months and a fine of Rp. 500,000 (five hundred thousand rupiahs) (Helmi, 2019).

Lubuk Basung District Court judges should make Constitutional Court Decision Number 35/PUU-X/2012 and MK Decision 95 / PUU-XII / 2014 as a reference in deciding the case above. In essence, this Constitutional Court Decision is an embodiment of protection provided to customary law communities. Otherwise, Lubuk Basung Court judges sentenced the community who logged tree in its forest. This indicates that security and recognition of indigenous peoples' rights have not been realized maximum, even after the Constitutional Court Decision Number 35 / PUU-X / 2012, which is used as a decision that recognizes indigenous peoples' rights (Helmi, 2019).

Conclusion

That the rights of indigenous peoples to land and resources should be respected It is time for natural resources to become part of public services Unique treatment. That is because of the indigenous peoples Inseparable direct land relations and Natural resources, of which the forest question is one. Forestry Does indigenous peoples have a social and economic role. Land Is a natural resource used as a landmark of life, and Livestock for aboriginal people living in and around Forests in the form of customary forests known as the ulayat property. Because, Because The Constitutional Court has played its part through its decision In the defense of citizens' civil rights (Society Adat) in the creation of the rule of law. The gamut of the The Faction which is also the applicant for judicial review Demonstrated that the Constitutional Court is the venue for Different groups fighting for their interests. This is why, it means Constitutional Court ruling on reinforcing Group rule Adat on land and natural resources really has to be done by all parties, especially in the field of public services The Government's cornerstone for the greatest prosperity possible.

References

- Arrsa, R. (2014). Concurrent elections and the future of democratic consolidation. Jurnal Konstitusi, 11(3), 515–537.

- Hanadi, S. (2019). The authority of the constitutional court in interpreting the 1945 constitution of the republic of Indonesia. Ekspose: Jurnal Penelitian Hukum Dan Pendidikan, 16(1), 349-362.

- Helmi, M.I. (2019). The settlement of a judicial review case in the constitutional court. SALAM: Jurnal Sosial Dan Budaya Syar-I, 6(1), 97–112.

- Jaelani, A.K., Gusti, I., Ketut, A., Handayani, R., & Karjoko, L. (2019). Executability of the constitutional court decision regarding grace period in the formulation of legislation. International Journal Of Advanced Science And Technology, 28(15), 816–823.

- Jaelani, A.K., Gusti, I., Ketut, A., Handayani, R., & Karjoko, L. (2020). Development of tourism based on geographic indication towards to welfare state. International Journal Of Advanced Science And Technology, 29(3S), 1227–1234.

- Jatmiko, D.R., Hartiwiningsih, & Handayani, G.A.K.R. (2019). A political communication regulation model in local leaders election and legislative election for realizing a just political education. International Journal Of Advanced Science And Technology, 28(20), 349–352.

- Kadir, J., Gusti, I.A.K., & Rachmi, H.L.K. (2020). The political law of the constitutional court in canceling the concept of the four pillars as an pancasila as the state foundation. Talent Development & Excellence, 2(2), 1314–1321.

- Kadir, J.A., Gusti, A.K., & Rachmi, H.I. (2019). Regulation of regional government on halal tourism destinations in West Nusa Tenggara province after constitutional court decision number 137/PUU-XIII/2015.

- Karjoko, L., Winarno, D.W., Rosidah, Z.N., & Handayani, I.G.A.K.R. (2020). Spatial Planning dysfunction in east kalimantan to support green economy. International Journal Of Innovation, Creativity And Change, 11(8), 259–269.

- Leonard, T., Pakpahan, E.F., Heriyati, K.L., & Handayani, I.G.A.K.R. (2020). Legal review of share ownership in a joint venture company. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 11(8), 332–345.

- Putri, P.M., Handayani, I.G.A.K.R., & Novianto, W.T. (2019). Legal protection for HIV/AIDS patients in indonesian medical services. International Journal Of Advanced Science And Technology, 28(20), 534–539.

- Ruman, Y.S. (2012). Legal justice and its application in court. Humaniora, 3(2), 345-359.

- Soediro. Handayani, I.G.A.K.R., & Karjoko, L. (2020). The spatial planning to implement sustainable agricultural land. International Journal Of Advanced Science And Technology, 29(3SI), 1307–1311.

- Sudrajat, T. (2019). Harmonization of regulation based on pancasila values through the constitutional court of Indonesia. Constitutional Review, 4(2), 301-312.