Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

The Effect of Brand Personality on Consumer Self-Identity the Moderation Effect of Cultural Orientations among British and Chinese Consumers

Samer Hamadneh, School of Business, The University of Jordan

Jamal Hassan, Progressive Partnership, Edinbrugh

Muhammad Alshurideh, School of Business, The University of Jordan & College of Business Administration, University of Sharjah

Barween Al Kurdi, Hashemite University

Ahmad Aburayya, Dubai Health Authority

Abstract

Brands are perceived to possess a personality that consumers choose to self-express and thus create their self-identities. Despite the extensive research that suggests that the self-expression can be a key driver for brand choice and preference, little research has been conducted to understand the role brands play in constructing consumers self-identity. This study attempts to address this gap by examining the relationship between brand personality and consumer self-identity. Further, the study adopts an international perspective by establishing how consumer cultural orientations can moderate such relationship amongst Chinese and British consumers. The study adopts a quantitative research design and uses an online survey to assess the effect of brand personality on consumer identity. In total, 139 participants took part, with 85 from the UK and 54 from China. A number of statistical tests were conducted, including an analysis of variance, t-test, Cronbach’s Alpha and means were computed. The showed that the effect of brand personality was insignificant. However, the results found that the differences between the UK and China were evident. The study offers some managerial advice to brand managers and marketers operating in global markets.

Keywords

Brand Personality, Consumer Identity, National Culture, CCT, Brand Personality Big Five Model, Compensatory Consumer Behaviour Model

Introduction

Brands are perceived to possess a personality that consumers choose to self-express and thus create their self-identities (Phau & Lau, 2001; Alshurideh et al., 2015; Matzler et al., 2016; Aburayya et al., 2020; Abu Zayyad et al., 2020; Al-Khayyal et al., 2020). Increasingly, marketers strive to create strong personalities for their brands to influence consumers’ purchasing choices (Black & Veloutsou, 2017; Alaali et al., 2021; Aljumah, Nuseir & Alshurideh, 2021; Mouzaek et al., 2021; Sweiss et al., 2021). For example, Pepsi has stressed for years to consumers that drinking Pepsi Cola will enable them to restore their vitality (Keller, 1999). Hence, brand personality helps marketers to differentiate their brands from other competitor brands in a particular product category. While earlier research has indicated that the self-expression can be a key driver for brand choice and preference (e.g., (Kleine, Kleine & Kernan, 1993; Berger & Heath, 2007; Al Kurdi & Alshurideh, 2021)), little research has been conducted to understand the role brands play in constructing consumers self-identity (Chernev, Hamilton & Gal, 2011). Therefore, the first objective of this paper is to examine the effect of brand personality on consumer self-identity. Understanding the relationship between brand personality and consumer self-identity is important because having positive relationships with brands, consumers will construct their identity towards these brands which in turn can affect their buying intentions (Matzler et al., 2016).

The paper also explores the moderating effect of cultural orientation on the relationship between brand personality and consumer self-identity by building on the effects of individualism and collectivism dimensions (Triandis, 1996). Indeed, earlier research noted that while individualists and collectivists use brands to express their identity, their motives may not be the same (Aaker, 1997; Schmitt, 2012; Abuhashesh, Alshurideh & Sumadi, 2021). This provides the ground for the possibility that consumers’ cultural orientations may affect the relationship between brand personality and consumer self-identity (Joy, 2001). However, despite the importance of cross-cultural differences, their influence on the effectiveness of brand personification strategies is often overlooked (Aguirre-Rodriguez, 2014; Matzler et al., 2016). Consequently, (Phau & Lau, 2001) have called for further research to understand how individual culture can moderate the relationship between brand personality and consumer behaviour. Hence, the second objective of this study is to examine such variations by comparing between Chinese and British consumers to determine whether individual culture can moderate the relationship between brand personality and consumer self-identity. By doing so, the study contributes to the current knowledge by offering an international perspective on the examined phenomenon.

Literature Background

Brand Personality

Brand personality has been commonly defined as the human characteristics associated with a brand (Aaker, 1997; Joy, 2001). While this definition suggests that human and brand personality traits can share similar conceptualization (Epstein, 1979), they are different in terms how they are formed (Aaker, 1997). Perceptions of human personality traits are reflection on individual physical and demographic characteristics, values and beliefs (Park & Lessig, 1981). In contrast, brand personality traits are developed by any direct or indirect contact that the consumer has with the brand (Plummer, 1985). Unlike product related features which tend to serve a utilitarian function for consumers, brand personality tends to serve as symbolic and self-expression function (Keller, 1993). In this sense, brand personality can be described as a brand association that illustrates the symbolic consumption and the emotional connections that consumers establish with a brand.

Extant literature has demonstrated that brand personality can be developed via multiple marketing variables such as building emotional strategies (e.g., brand love) (Bairrada, Coelho & Lizanets, 2019) and advertising, packaging sponsorships and symbols (Elliott & Wattanasuwan, 1998; AlSuwaidi et al., 2021; Salloum et al., 2021). The most prominent understanding of the brand personality construct is derived from the Big Five human personality dimensions (Eisend & Stokburger-Sauer, 2013). This theory posits that individual differences in sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication and ruggedness are stable traits throughout most of the adult life span (Obeidat, Z., Alshurideh, M., Al Dweeri, R., Masa’deh, no date; McCrae & John, 1992; McCrae and Costa, 2003). Furthermore, this conceptualization of brand personality has since then been used in a large number of studies (Eisend & Stokburger-Sauer, 2013). Each facet was different and focused on a certain aspect of a brand’s personality. In the present study, the construct of brand personality is examined considering its five dimensions.

Previous research has highlighted the importance of brand personality and how this concept enables consumers, through the engagement with a brand, to express his or her own self (Belk, 1988) or an ideal-self (Malhotra, 1988). In this sense, brand personality allows consumers to express themselves and enhance their self-concept, thus reflecting their identities (Kim, Han & Park, 2001). As argued by (Chaplin & Roedder John, 2005), consumers view brands as extensions of themselves. This suggests a direct link between brand personality and consumer self-identity. As consumers may use brands to express their identities, it has been argued that marketers need to reposition their products from focusing merely on functional satisfaction into focusing on repositioning these brands as means of self-expression (Chernev, Hamilton & Gal, 2011). The next section thus reviews the literature on consumer self- identity.

Consumer Self-Identity

Exploring the research focusing on the notion of consumer identity can be related to consumer culture theory CCT (Arnould & Thompson, 2005). The theory is concerned with understanding how consumers behave and make choices from a social and cultural point of view. It primarily integrates a family of theoretical perspective, aiming to unfold the complexities of symbolic consumption, acquisition, and possession. CCT posits that consumption is not a simple practice and involves multiple motives, one of which can aid a consumer’s sense of identity through possessions (McCracken, 1986; Holbrook, 1987; Belk, 1988; Al-Maroof et al., 2021a; Al-Maroof et al., 2021b). In this sense, consumers actively shape and transform the encoded meanings in brands and material goods to construct their identity on both an individual and collective level (Thompson & Hirschman, 1995; Cherrier & Murray, 2002; Jensen Schau & Gilly, 2003). Another consumer related theory which suggests a direct relationship between brand personality and consumer self-identity is the compensatory consumer behaviour model (Mandel et al., 2017). This theory postulates that any consumption activity is motivated by a desire to offset or reduce a self-discrepancy. A self-discrepancy is an incongruity between how individuals currently perceive themselves and how they desire to view themselves (Higgins, 1987). For example, as consumers will feel a sense of self-discrepancy in relation to their ideal self, a compensatory act will follow in order to rectify the inconsistency. The ideal self and one’s identity can be boosted, much like self-esteem, and revert to a stable state (Higgins, 1987). This is another example of how the consumer’s identity can be affected by the power of brands personality which can serve as means to construct consumers’ self-identity. This shows a causal relationship between the consumer’s identity formation and the possessions chosen to be acquired. Consequently, such causality can underline the brand personality and the strength and influence of its characteristics, affecting the consumer’s sense of identity.

The concept of personality is of particular importance when understanding consumers’ identity. This is because personality affects how people behave and determine their pattern of interaction in the environment (McKenna & Bargh, 2000; Alshurideh et al., 2020; Alzoubi et al., 2020). The five-factor model (McCrae & Costa, 1987) has been widely accepted framework to evaluate personality by reflecting how an individual ranks on five personality-based traits. These traits are openness (i.e., a person readiness to accept new ideas) conscientiousness (i.e., one’s propensity to focus on achievement, being organized, careful, and responsible), extraversion (i.e., an individual’s desire to be social and interactive), agreeableness (i.e., an individual tendency toward being courteous and cooperative with others), and neuroticism (i.e., one’s proneness to depression, and distress) (Islam, Rahman & Hollebeek, 2017). The individual traits within each factor allow for a deeper understanding of a person’s identity. If the personality of a brand is congruent with the consumer’s personality, that consumer becomes attached to the brand because it reflects who he or she believes that he or she is (Yao, Chen & Xu, 2015). Consumer researchers have established for a long time that individuals consume in ways that are consistent with their sense of self (Sirgy, 1982; Belk, 1988; Bettayeb, Alshurideh & Al Kurdi, 2020; Kurdi, Alshurideh & Alnaser, 2020; Al Kurdi et al., 2021). Leading scholars have reported that consumers use possessions and brands to create their self-identities (e.g., (Belk, 1988; McCracken, 1989; Fournier, 1998; Bettayeb, Alshurideh & Al Kurdi, 2020)), and thus establishing a relationship between self-concept and consumer brand choice. As possessions and brands add to one’s identity (Kleine, Kleine III & Allen, 1995), the act of consumption can be seen as much more than a behaviour. As argued by (Elliott & Wattanasuwan, 1998), brands and products play a vital role in supplying symbolic meanings for constructing consumers self-identities.

However, consumers have a part to play in influencing how brand personality is perceived and reflected on their identities (Phau & Lau, 2001). For example, buying an electric car may symbolise “I care for the environment”. Hence, it can be argued that the deeper meaning embedded in certain brands can evoke consumers to feel emotionally attached, leading to the fulfilment of their identity in some capacity. In other words, the brand can provide a sense of security and offer the consumer a renewed purpose within their identity and self (Belk, 1988). As consumers continue to purchase and acquire possessions, their ideal self-identity takes form and a process is in motion to self-completion (Alshurideh, 2014; Alshurideh et al., 2019; Al-Dhuhouri et al., 2020; Alkitbi et al., 2020; Alsharari & Alshurideh, 2020; Kurdi, Alshurideh & Alnaser, 2020).

On the other hand, recent research demonstrates that culture can impact brand personality perceptions. Some studies suggest that consumers in different cultural contexts may associate with different culturally relevant brand personality traits (Aguirre-Rodriguez, 2014). The next section reviews the literature on cultural orientations and brand personality and proposes that cultural orientations can have a moderating effect in studying the relationship between brand personality and consumer self-identity.

Cultural Orientations and Brand Personality

Previous literature has emphasized the importance of the relationship between brand personality and culture (Phau & Lau, 2001). However, despite the importance of cross-cultural differences, their influence on the effectiveness of brand personification strategies is often overlooked (Aguirre-Rodriguez, 2014; Matzler et al., 2016). In his seminal work on comparing national cultures. (Hofstede, 1991) defined culture as “the collective mental programming of the human mind which distinguishes one group of people from another” (1991:3). His tools allow some generalisability between national cultures, if made strictly in the context of comparison between national cultures. Usually, culture illustrates differences between the concepts of self, personality, and identity, which has been used by previous scholars to examine variations in branding strategies and communications (De Mooij & Hofstede, 2010).

Hofstede (1991); Hofstede (1980) defined some cultural differences along some cultural dimensions including: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism versus collectivism, and masculinity versus femininity. Some authors highlighted the role of cultural orientation in consumer-brand relationships (e.g., (Aguirre-Rodriguez, 2014; Lam, Ahearne & Schillewaert, 2012)). This study investigates the effect of brand personality on consumer self-identity with the objective of determining the significance of the effect by comparing consumers from the UK and China. Specifically, the study focuses on the individualism versus collectivism cultural dimension while comparing between the UK and Chinese consumers as the distinction between individualistic and collectivist societies is vital to the cross-cultural understanding of consumer behaviour (Maheswaran & Shavitt, 2000). Further, previous research has asserted that such distinction is one of the most relevant cultural dimensions in the context of brand personification strategies (Aguirre-Rodriguez, 2014).

The individualism versus collectivism dimension refers to the relationship one perceives between one’s self and the group one belongs to (Hawkins, Best & Coney, 2001). The notion of individualism describes how individuals in a society are independent and autonomy is encouraged (Mills & Clark, 1982). It has been noted that individualistic cultures tend to consider the individual self as the basic unit and a source of life identity and purpose ((Hofstede, 1991; Kagitcibasi, 1997; Al-Dhuhouri et al., 2020; Turki et al., 2021)). In contrast, the collectivism culture features interdependent behaviors within groups or families (Schwartz, 1994). Hence, members of collectivist cultures emphasize their group membership, respect group processes and decisions, and expect others to protect them if they need help. The UK inherits a culture of individualism whilst China leans in the direction of collectivism (Sun, Horn & Merritt, 2004; Hofstede, Hofstede & Minkov, 2010).

Previous consumer cross cultural research has generally reported some differences between Chinese and western consumers. According to (Sun, Horn & Merritt, 2004), British and US consumers have higher tendency to stick with well-known brand names than Chinese consumers. (Aaker & Schmitt, 2001) found that Chinese use products to show their belonging to the group more. These examples suggest that cultural orientations may have a moderating effect on how brand personality affect consumer self-identity. However, although some research has theorized about the role of culture in consumer-brand relationships, empirical research is still very limited (Lam, Ahearne & Schillewaert, 2012). Hence, this paper adopts a cross cultural research design and specifically seeks to understand whether individualistic and collectivist cultures can shape the relationship between brand personality and consumer self-identity.

Having provided the theoretical context, which underlines this study, we thus hypothesize:.

H1 Brand personality have a direct effect on consumers’ self-identity.

H2 Consumer cultural orientations moderate the relationship between brand personality and consumers self-identity.

Methods

Data Collection and Study Sample

An online survey was designed to collect quantitative data through the use of a Likert scale. The online survey software known as Qualtrics was used to build the survey and allow for easy distribution and data collection. This software is useful as it allows for a simple, interactive design; where all participants feel comfortable whilst completing the questionnaire. Qualtrics provides an online link in order to share the questionnaire with the intended sample, tracking response rate and collecting the data from the online platform.

The sample targeted people from the UK and China. The questionnaire was distributed through social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter, with participation being completely voluntary. As these were the only channels used in distribution, the sample was reliant on active users of these social media platforms to engage with the study. The questionnaire required participants to declare being from either the UK or China. The standard demographic questions were also asked of the sample, age and gender. The sample criteria w specific and selective in order to be able to effectively come to a conclusion regarding the research objective. In total, there were 139 participants. 85 participants from the UK and 54 from China. Coincidentally, there were 54 male participants and 85 female participants. 28 males and 57 females from the UK sample. 26 males and 28 females from the Chinese sample. The age range of participants is 18-63 years old.

Study Instrument

A survey instrument was utilized to examine the effect of brand personality on consumers’ self-identity. The survey consisted of 20 items for measuring the theoretical constructs presented in this study. The source of the constructs of the first ten questions related directly to the consumer culture theory and the compensatory consumer behavior models. However, the other ten questions were directly linked to the big five model and the dimensions of human personality. The dimension of human personality relates to the participant’s personality and identity. This was important as it gives insight into the participant’s self-awareness and ultimately how they feel about their own identity.

Research Quality

The reliability of results concerns their consistency over time and the extent of representation within the total population (Golafshani, 2003; Taryam et al., 2020; Capuyan et al., 2021; Taryam et al., 2021). The Cronbach’s alpha test was conducted to generate a coefficient and check the internal reliability of the scale use in the present study. The reliability coefficient ranges between 0 and 1; an alpha value greater than 0.7 implies that the data is reliable. As the questionnaire used a Likert scale, the Cronbach’s alpha is recommended.

Research validity was maintained by ensuring that measurements made for each of the relevant to the context surrounding the study. There are two forms of validity: internal and external (Bell, Bryman & Harley, 2018). The internal validity concerns the relationship between the independent and dependent variable. Whereas external validity can be applied to the generalisability and strength of the research methods used. In the present study, the measures and concepts used were leading in the field and esteemed in terms of longevity. Of the specific theories used to provide the foundation, all bar one were developed and supported over many years. The validity of this research is assured by the fact that the conceptualizations are solid and robust.

Findings and Discussion

The purpose of the study was to investigate whether brand personality affect a consumer’s self-identity, whilst comparing the results with the international element provided by the target sample. Parametric tests were conducted to analysis the results from different statistical standpoints and make sense of the data collected. The statistical tests carried out were; descriptive statistics, independent sample t-test, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality, one-way analysis of variance, univariate analysis of variance. The tests were chosen due to the nature of the data set and the variables involved. The measurement of the effect of brand personality on consumer identity, as well as the comparison between the UK and China.

The demographic data shows a higher percentage of the participants to be female compared to males, (62.2%, N=85 females, 38.8, N=54 male). The same percentage can be seen with regard to the nationality of the participants (62.2% UK, 38.8% China). However, when looking into the make-up of each of the nationalities; it becomes clear that the UK female population are the majority respondents. Table 1 illustrates the demographic data of all the participants who took part in the questionnaire. The proportion of females for both nationalities is greater than that of their male counterparts. Out of the 139 participants 40.01% were females from the UK, double that of any other subset in the demographic data. The questionnaire was distributed through social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter, with participation being completely voluntary. As these were the only channels used in distribution, the sample was reliant on active users of these social media platforms to engage with the study.

| Table 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Nationality | Gender | N | Overall percentage |

| UK | Male | 28 | 20.14 |

| Female | 57 | 40.01 | |

| China | Male | 26 | 18.71 |

| Female | 28 | 20.14 | |

An independent samples t-test was conducted to generate mean scores and a standard deviation. The average score for two groups of participants differed greatly, the UK (M=7.99, SD=8.75) compared to the low score from the Chinese participants (M=1.06, SD=8.09). This produces a low positive overall average (M=5.29). The scores had a range of 48 (-17 to 31). The scores indicate that the UK participants’ consumer identities were influenced to a greater extent by brand personality. The mean scores differ emphasizing the difference in response types amongst the two groups of participants. The results are in support of the hypothesis as there is clear difference between the groups and brand personality influencing consumer identity.

The total and mean average score were calculated to aid the examination of the effect of brand personality on consumer identity. The mean average can act as a point of call when determining the role of the variables and how they may relate to wider theoretical concepts. Table 2 illustrates the group statistics showing the number of participants, mean and standard deviation for both the UK and China. The table reveals that the total mean score for the UK is much greater than the mean of China, with 85 UK participants compared to 54 Chinese participants. Whilst the standard deviation is fairly similar, the remaining statistics showcase the differences between the two groups of participants.

| Table 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Statistics | ||||

| Nationality | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| Questionnaire | UK | 85 | 7.9882 | 8.7457 |

| Score | China | 54 | 1.0556 | 8.0854 |

The mean scores for each question were calculated. With the use of the Likert scale and the scoring of; +2 strongly agree, +1 agree, 0 neither agree nor disagree, -1 disagree and -2 strongly disagree. The UK scores are greater in value for all questions expect Q9 (I buy brands/products to fit in). The higher UK scores show that their consumer identity is influenced by brand personality. The Chinese participants less so as the results show lower scores indicating less of an influence being found.

| Table 3 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean Scores Per Question | ||

| Question number | UK | China |

| Q1 | 0.53 | -0.22 |

| Q2 | 0.53 | -0.24 |

| Q3 | 1.06 | -0.35 |

| Q4 | -0.06 | 0.17 |

| Q5 | 0.32 | 0.15 |

| Q6 | 0.38 | -0.11 |

| Q7 | 0.68 | 0.7 |

| Q8 | -0.58 | -0.52 |

| Q9 | -0.53 | 0.72 |

| Q10 | 0.51 | -0.15 |

| Q11 | 0.73 | 0.59 |

| Q12 | 0.74 | -0.35 |

| Q13 | 0.99 | 0.54 |

| Q14 | 0.46 | 0.02 |

| Q15 | -0.15 | -0.37 |

| Q16 | 0.89 | -0.48 |

| Q17 | 1.24 | 0.78 |

| Q18 | -0.12 | -0.76 |

| Q19 | 1.08 | 1.19 |

| Q20 | -0.71 | -0.24 |

| Mean | 0.39 | 0.05 |

The mean scores per question were calculated to highlight the vast difference between the two groups of participants (table 3). The overall mean score for the UK participants (M=0.39) is considerably higher in value compared to the participants from China (M=0.05). As the Likert scale was used and all the questions were positively scored, a high score corresponds to brand personality having an effect on consumer identity. When looking at the scores for each individual question, the UK scored a more positive response for all questions except Q7 (my possessions have meaning beyond their utility), Q9 (I buy certain brands to fit in), and Q19 (I would describe my personality as agreeable and kind). Furthermore, the majority of responses from the Chinese participants are negative in nature; leading to the assumption that their identity is not affected by brand personality.

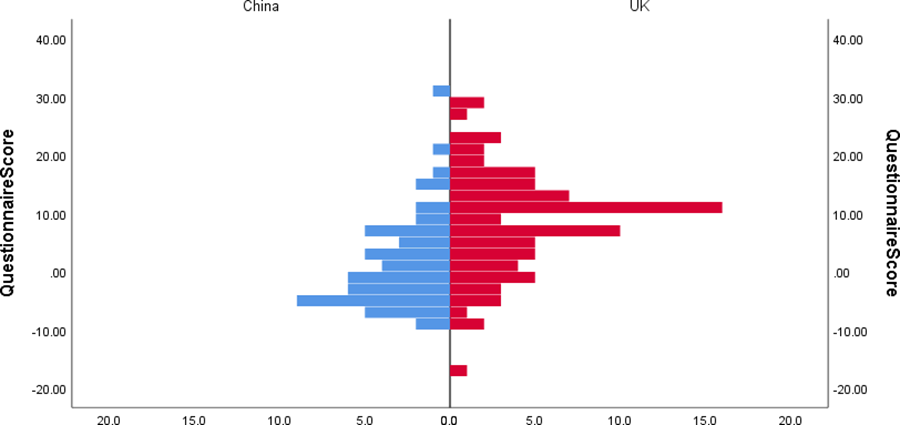

Figure 1 describes the overall scores from all the participants to complete the questionnaire. It serves as a useful comparison between the two nations showing the spread of each set of data. The participants from China tend to score more negatively with the cluster of data towards the lower end of the scale. In contrast, the UK participants score mostly positively with the cluster spread over a range of scores.

| Table 4 | |

|---|---|

| Overall Mean Scores | |

| Mean | |

| UK | 7.99 |

| China | 1.06 |

| Overall | 5.29 |

Table 4 above illustrates the overall mean scores for the questionnaire. The total was calculated for each nation as well as an overall score. All three mean averages show a positive figure; therefore, the concept of brand personality affects consumer identity. The UK mean average is considerably higher than the Chinese participants, this lends to the overall score being positive. These scores show that brand personality had an effect and influenced the participants’ consumer identity.

| Table 5 | |

|---|---|

| Overall Mean Scores For Question Areas | |

| Question area | Mean |

| Q1-10 | 0.18 |

| Q11-15 | 0.37 |

| Q16-20 | 0.33 |

By splitting the questionnaire into three areas, based on the conceptual framework developed, the results can be more easily interpreted. Questions 1-10 are related to consumer culture theory (Arnould & Thompson, 2005) and the compensatory consumer behavior model (Mandel et al., 2017). Questions 11-15 directly draw from the brand personality big five model (Aaker, 1997), whilst the last set of questions 16-20 are based on five factor model (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Tables 4 and 5 illustrate the mean scores from the questionnaire overall and comparing the UK with China. The overall mean scores, as shown in table 5, are all positive in nature and signify that brand personality affects consumer identity. Although the scores are not highly positive it gives credibility to the argument of influence between the two variables.

| Table 6 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean Scores For Question Areas – Uk And China | ||

| Question area | UK Mean | China Mean |

| Q1-10 | 0.28 | 0.02 |

| Q11-15 | 0.55 | 0.2 |

| Q16-20 | 0.48 | 0.09 |

The mean score per question area comparison between the UK and China as seen in table 6, which shows that in all areas the two groups finish with a positive average. The differences lie with the extent of positivity in the scores. The UK participants’ scores are considerably higher. The participants from China show positive scores however, the first and last question areas are extremely close to the value of 0 which corresponds to ‘neither agree nor disagree’. This suggests that the influence of brand personality on consumer identity amongst the Chinese participants was to a much lesser extent.

Regarding the test for normality, a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted in order to assess normal distribution in the data set. For the UK participants (KS=0.09, df=85, p=0.05) the data did not differ significantly from normal distribution. As for the participants from China (KS=0.13, df=54, p=0.03) there is a slight differential from normal distribution as the p value is low. Assumptions of the data were tested via the homogeneity of variance. The Levene’s test showed that the assumptions were not violated (F=(1, 137)=0.46, p=0.5).

A reliability between subject test was carried out, a one-way analysis of variance to determine if the difference between the mean scores are statistically significant. A non-significant result was found when comparing the groups of participants and the effect of brand personality on consumer identity [F (1587, 9889)=21.99, p=0.00]. A reliability analysis was carried out on the scale used in the questionnaire measuring the effect of brand personality on consumer identity. The scale comprised of 20 items in total. Cronbach’s Alpha showed the questionnaire to reach an acceptable level of reliability, α=0.81. Most items were deemed worthy of retention showing a decrease in alpha if deleted.

Implications and Limitations

The study responds for further research calls towards more understanding to the relationship between brand personality and consumers identifies (e.g., (Chernev, Hamilton & Gal, 2011; Phau & Lau, 2001)) and how cultural orientations moderate such relationship (e.g; (Matzler et al., 2016; Alameeri et al., 2020; Alyammahi et al., 2020; Al-Dhuhouri et al., 2021)). Hence, the study contributes to our knowledge on the relationship between brand personality and consumer self-identity. The study has reported that national culture can affect how consumers construct their self-concept and identities. It showed that adding an international comparative element produces a unique insight into the consumption behaviors and personalities of the participants. The study can offer marketeers and brands insight into the relationship of brand personality and consumer self-identity. Brands which seek to gain a worldwide presence should understand the national culture on the different sets of participants, whilst also considering the cultural adaptations a brand can make to appeal to certain consumer identities. Further, brand managers need to understand what drives consumption behaviors and the identities of their consumers.

As any study, this study has a number of limitations. First, the study adopted a quantitative research design, which in turn may not produce deeper insights into the relationship between brand personality and consumers self-identity. To fully understand brand personality in tandem with consumer identity, future studies could utilize a qualitative methodological approach to allow for participants to express their consumer identities and the brands which appeal to them. As consumer identity is entirely subjective and complex, an interview protocol will allow for further elaboration and deeper insight. Finally, further investigation into symbolism used by brands which effectively alters the consumer perception and identities, would allow for greater understanding in this field of study.

References

- Aaker, JL. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(1), 347–356.

- Aaker, J., & Schmitt, B. (2001). Culture-dependent assimilation and differentiation of the self: Preferences for consumption symbols in the United States and China. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 561–576.

- Abu Zayyad, H.M., Obeidat, Z.M., Alshurideh, M.T., Abuhashesh, M., Maqableh, M., & Masa’deh, R. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and patronage intentions: The mediating effect of brand credibility. Journal of Marketing Communications, 27(5), 510-533.

- Abuhashesh, M.Y., Alshurideh, M.T., & Sumadi, M. (2021). The effect of culture on customers’ attitudes toward Facebook advertising: The moderating role of gender. Review of International Business and Strategy.

- Aguirre-Rodriguez, A. (2014). Cultural factors that impact brand personification strategy effectiveness. Psychology& Marketing, 31(1), 70–83.

- Al-Dhuhouri, A., Fatima, S., Alshurideh, M., Al Kurdi, B., & Salloum, S.A. (2020). Enhancing our understanding of the relationship between leadership, team characteristics, emotional intelligence and their effect on team performance: A critical review. International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics, 644–655.

- Al-Maroof, R.S., Alhumaid, K., Alhamad, A.Q., Aburayya, A., & Salloum, S. (2021). User acceptance of smart watch for medical purposes: An empirical study. Future Internet, 13(5), 1–19.

- Al Kurdi, B.H., & Alshurideh, M.T. (2021). Facebook advertising as a marketing tool: Examining the influence on female cosmetic purchasing behaviour. International Journal of Online Marketing (IJOM), 11(2), 52–74.

- Al Kurdi, A., Barween, Alshurideh, M., Nuseir, M., Aburayya, A., & Salloum, S.A. (2021). The effects of subjective norm on the intention to use social media networks: An exploratory study using PLS-SEM and machine learning approach. Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications: Proceedings of AMLTA 2021, 581–592. Springer International Publishing.

- Alameeri, K., Alshurideh, M., Al Kurdi, B., & Salloum, S.A. (2020). The effect of work environment happiness on employee leadership. International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics, 668–680. Springer.

- Aljumah, A., Nuseir, M.T., & Alshurideh, M.T. (2021). The impact of social media marketing communications on consumer response during the COVID-19: Does the brand equity of a university matter. The Effect of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) on Business Intelligence, 334, 384–367.

- Alkitbi, S.S., Alshurideh, M., Al Kurdi, B., & Salloum, S.A. (2020). Factors affect customer retention: A systematic review. International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics, 656–667. Springer.

- Alsharari, N.M., & Alshurideh, M.T. (2020). Student retention in higher education: The role of creativity, emotional intelligence and learner autonomy. International Journal of Educational Management, 35(1), 233–247.

- Alshurideh, M., Kurdi, B.A., Shaltoni, A.M., & Ghuff, S.S. (2019). Determinants of pro-environmental behaviour in the context of emerging economies. International Journal of Sustainable Society, 11( ), 2 7-277.

- Alshurideh, M., Gasaymeh, A., Ahmed, G., Alzoubi, H., & Kurd, B. (2020). Loyalty program effectiveness: Theoretical reviews and practical proofs. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 8(3), 99- 12.

- Alshurideh, M. (2014). Do we care about what we buy or eat? A practical study of the healthy foods eaten by Jordanian youth. International Journal of Business and Management, 9(4), 65.

- Alshurideh, M., Bataineh, A., Al kurdi, B., & Alasmr, N. (2015). Factors affect mobile phone brand choices–Studying the case of Jordan universities students. International Business Research, 8(3), 141–155.

- AlSuwaidi, S.R., Alshurideh, M., Al Kurdi, B., & Aburayya, A. (2021). The main catalysts for collaborative R&D projects in dubai industrial sector. The International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision, 795–806.

- Alyammahi, A., Alshurideh, M., Al Kurdi, B., & Salloum, S.A. (2020, October). The impacts of communication ethics on workplace decision making and productivity. In International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics, 88- 00. pringer, Cham.

- Alzoubi, H., Alshurideh, M., Kurdi, B.A., & Inairat, M. (2020). Do perceived service value, quality, price fairness and service recovery shape customer satisfaction and delight? A practical study in the service telecommunication context. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 8(3), 579–588

- Arnould, E.J., & Thompson, C.J. (2005). Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): Twenty years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 868–882.

- Bairrada, C.M., Coelho, A., & Lizanets, V. (2019). The impact of brand personality on consumer behavior: The role of brand love. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 23(1), 30–47.

- Belk, R.W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168.

- Bell, E., Bryman, A., & Harley, B. (2018). Business research methods. Oxford university press.

- Berger, J., & Heath, C. (2007). Where consumers diverge from others: Identity signaling and product domains. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 121–134.

- Bettayeb, H., Alshurideh, M.T., & Al Kurdi, B. (2020). The effectiveness of mobile learning in UAE Universities: A systematic review of motivation, self-efficacy, usability and usefulness. International Journal of Control and Automation, 13(2), 1558–1579.

- Black, I., & Veloutsou, C. (2017). Working consumers: Co-creation of brand identity, consumer identity and brand community identity. Journal of Business Research, 70, 416–429.

- Capuyan, D.L., Capuno, R.G., Suson, R., Malabago, N.K., Ermac, E.A., Demetrio, R.A.M., … & Medio, G.J. (2021). Adaptation of innovative edge banding trimmer for technology instruction: A university case. World Journal on Educational Technology, 13(1), 31–41.

- Chaplin, L.N., & Roedder John, D. (2005). The development of self-brand connections in children and adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(1), 119–129.

- Chernev, A., Hamilton, R., & Gal, D. (2011). Competing for consumer identity: Limits to self-expression and the perils of lifestyle branding. Journal of Marketing, 75(3), 66–82.

- Cherrier, H., & Murray, J. (2002). Drifting away from excessive consumption: a new social movement based on identity construction. ACR North American Advances.

- De Mooij, M., & Hofstede, G. (2010). The Hofstede model: Applications to global branding and advertising strategy and research. International Journal of Advertising, 29(1), 85–110.

- Eisend, M., & Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. (2013). Brand personality: A meta-analytic review of antecedents and consequences. Marketing Letters, 24(3), 205–216.

- Elliott, R., & Wattanasuwan, K. (1998). Brands as symbolic resources for the construction of identity. International Journal of Advertising, 17(2), 131–144.

- Epstein, S. (1979). The stability of behavior: I. On predicting most of the people much of the time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(7), 1097–1126.

- Fournier, S. (1998). Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 343–373.

- Golafshani, N. (2003). Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 8(4), 597–607.

- Hawkins, D.I., Best, R.J., & Coney, K.A. (2001). Consumer behavior: Building marketing strategy. Richard D. Irwin. Inc.

- Higgins, E.T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Revised and expanded, (3rd edition). McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: The software of the mind. New York, London, McGraw-Hill.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences. Thousand Oaks, Calif. Sage.

- Holbrook, M.B. (1987). What is consumer research? Journal of Consumer Research, 14(1), 128–132.

- Islam, J.U., Rahman, Z., & Hollebeek, L.D. (2017). Personality factors as predictors of online consumer engagement: An empirical investigation. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 35(4), 510–528.

- Jensen Schau, H., & Gilly, M.C. (2003). We are what we post? Self-presentation in personal web space. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(3), 385–404.

- Joy, A. (2001). Gift giving in Hong Kong and the continuum of social ties. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(2), 239–256.

- Kagitcibasi, C. (1997). Individualism and collectivism. Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 3, 1–49.

- Keller, K.L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22.

- Keller, K.L. (1999). Managing brands for the long run: Brand reinforcement and revitalization strategies. California Management Review, 41(3), 102–124.

- Kim, C.K., Han, D., & Park, S.B. (2001). The effect of brand personality and brand identification on brand loyalty: Applying the theory of social identification. Japanese Psychological Research, 43(4), 195–206.

- Kleine III, R.E., Kleine, S.S., & Kernan, J.B. (1993). Mundane consumption and the self: A social-identity perspective. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2(3), 209–235.

- Kleine, S.S., Kleine III, R.E., & Allen, C.T. (199 ). How is a possession “me” or “not me”? Characterizing types and an antecedent of material possession attachment. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(3), 327–343.

- Kurdi, B, Alshurideh, M., & Alnaser, A. (2020). The impact of employee satisfaction on customer satisfaction: Theoretical and empirical underpinning. Management Science Letters, 10(15), 3561–3570.

- Lam, S.K., Ahearne, M., & Schillewaert, N. (2012). A multinational examination of the symbolic--instrumental framework of consumer--brand identification. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(3), 306–331.

- Maheswaran, D., & Shavitt, S. (2000). Issues and new directions in global consumer psychology. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9(2), 59–66.

- Malhotra, N.K. (1988). Self-concept and product choice: An integrated perspective. Journal of Economic Psychology, 9(1), 1–28.

- Mandel, N., Rucker, D.D., Levav, J., & Galinsky, A.D. (2017). The compensatory consumer behavior model: How self-discrepancies drive consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(1), 133–146.

- Matzler, K., Strobl, A., Stokburger-Sauer, N., Bobovnicky, A., & Bauer, F. (2016). Brand personality and culture: The role of cultural differences on the impact of brand personality perceptions on tourists’ visit intentions. Tourism Management, 52, 507–520.

- McCracken, G. (1986). Culture and consumption: A theoretical account of the structure and movement of the cultural meaning of consumer goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(1), 71–84.

- McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 310–321.

- McCrae, R.R., & Costa, P.T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81.

- McCrae, R.R., & Costa, P.T. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. Guilford Press.

- McCrae, R.R., & John, O.P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 175–215.

- McKenna, K.Y.A., & Bargh, J.A. (2000). Plan 9 from cyberspace: The implications of the internet for personality and social psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(1), 57–75.

- Mills, J., & Clark, M.S. (1982). Exchange and communal relationships. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 121–144.

- Mouzaek, E., Alaali, N., A Salloum, S., & Aburayya, A. (2021). An empirical investigation of the impact of service quality dimensions on guests satisfaction: A case study of Dubai Hotels. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government, 27(3), 1186–1199.

- Obeidat, Z., Alshurideh, M., Al Dweeri., R., & Masa’deh, R. (2019). The Influence of online revenge acts on consumers psychological and emotional states: Does revenge taste sweet? IBIMA Conference Proceedings, Granada, Spain.

- Park, C.W., & Lessig, V.P. (1981). Familiarity and its impact on consumer decision biases and heuristics. Journal of Consumer Research, 8(2), 223–230.

- Phau, I., & Lau, K.C. (2001). Brand personality and consumer self-expression: Single or dual carriageway? Journal of Brand Management, 8, 428–444.

- Plummer, J.T. (1985). How personality makes a difference. Journal of Advertising Research, 24(6), 27–31.

- Salloum, S.A., AlAhbabi, N.M.N., Habes, M., Aburayya, A., & Akour, I. (2021, March). Predicting the intention to use social media sites: A hybrid SEM-machine learning approach. In International Conference on Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications (324-334). pringer, Cham.

- Schmitt, B. (2012). The consumer psychology of brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(1), 7–17.

- Schwartz, S.H. (1994). Beyond individualism/collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values.

- Sirgy, M.J. (1982). Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(3), 287–300.

- Sun, T., Horn, M., & Merritt, D. (2004). Values and lifestyles of individualists and collectivists: A study on Chinese, Japanese, British and US consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 21(5), 318–331.

- Sweiss, N., Obeidat, Z.M., Al-Dweeri, R.M., Mohammad Khalaf Ahmad, A.M., Obeidat, A., & Alshurideh, M. (2021). The moderating role of perceived company effort in mitigating customer misconduct within Online Brand Communities (OBC). Journal of Marketing Communications, 1–24.

- Taryam, M., Alawadhi, D., Al Marzouqi, A., & Aburayya, A. (2021). The impact of the covid-19 pandemic on the mental health status of healthcare providers in the primary health care sector in Dubai. Linguistica Antverpiensia, 2, 2995–3015.

- Thompson, C.J., & Hirschman, E.C. (1995). Understanding the socialized body: A poststructuralist analysis of consumers’ self-conceptions, body images, and self-care practices. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(2), 139–153.

- Triandis, H.C. (1996). The psychological measurement of cultural syndromes. American Psychologist, 51(4), 407.

- Alshurideh, M.T., Al Kurdi, B., & Salloum, S.A. (2021). The moderation effect of gender on accepting electronic payment technology: a study on United Arab Emirates consumers.Review of nternational Business and Strategy.

- Yao, Q., Chen, R., & Xu, X. (2015). Consistency between consumer personality and brand personality influences brand attachment. Social Behavior and Personality, 43(9), 1419–1428.