Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 2S

The Effect of Career Progression, Job Performance and Learning Development in Determining a High Potential Leader

Dyah Adhi Astuti, Universitas Pelita Harapan

Albert Surya Wanasida, Universitas Pelita Harapan

Rudy Pramono, Universitas Pelita Harapan

Keywords

Career Progression, Job Performance, Learning Development, High Potential Leader

Citation Information

Astuti, D.A., Wanasida, A.S., & Pramono, R. (2022). The effect of career progression, job performance, and learning development in determining a high potential leader. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 21(S2), 1-10.

Abstract

This study aims to analyze whether Career Progression (CP), Job Performance (JP), and Learning Development (LD) have an effect in determining a High Potential Leader (HPL), using secondary data. This research was conducted based on the population of branch managers who are currently active employees working at the bank. Employee data is obtained from a database stored in SAP, processed, and then analyzed using the Smart-PLS application. The results showed that secondary data can be used to help determine HPL, where the variable career progression and job performance have a positive effect on HPL while learning development does not have a positive effect on HPL. Considering that other variables can affect the determination of an HPL, it is further suggested that there is a need for research to include other variables such as age, gender, psychometric test results that might strengthen the testing of career progression, and job performance variables in testing their effect on HPL.

Introduction

One of the biggest challenges that an organization faces is to have human resources that beget leadership qualities or merely have the potential of becoming one, who presents characteristics that shows job performance and continuity towards the organization, as well as being able to face changes rapidly-specifically technological changes-over these few years (Santoso et al., 2020). The same goes for the banking world, with the progression of digital technologies, the demands for high-quality services have skyrocketed with the rise of “Challenger Bank” similar to the service offered by fintech, pushing banks to create breakthroughs that can immaculately improve the quality of service. The hyper-demanding and hyper-changing condition of this world label human resource to be a vital factor in keeping competition; and to have a leader with outstanding characteristics in their organization, is a key differentiator (Korn Ferry, 2020) of a leader with great potential, i.e., a keen learner, adaptable, has vision, and skillful in maintaining the dynamic of the team (King, 2018).

Considering the importance of having leaders and human resources who have the potential to become leaders (hereinafter in this study referred to as High Potential Leaders - HPL), the process of selecting and developing effective leaders becomes very crucial (Church & Conger, 2018). Furthermore, implementing assessment when determining HPL is becoming increasingly necessary in an organization (Bouland-van Dam, 2020; Charan, 2018). A concept introduced by Church & Silzer (2014), and is used in numerous studies as reference and identification of a potential leader (Bouland-van Dam, Oostrom, de Kock, Schlechter & Jansen, 2020), is The Leadership Potential Blueprint framework, that consists of three dimensions and six building blocks which are, foundational dimensions (cognitive variables, personality variable) (Church & Silzer, 2014; Church, 2014; Silzer & Church, 2017), growth dimensions (learning variable, motivation variable) (Church & Silzer, 2014; Church, 2014; Silzer & Church, 2017), which are the key traditional indicators in predicting HPL, and career dimensions (leadership skills, performance records, knowledge, and values variable) (Church & Silzer, 2014; Church, 2014; Silzer & Church, 2017), which is the dimension that can be further improved on (Bouland-van Dam, Oostrom, de Kock, Schlechter & Jansen, 2020).

To identify HPL, every organization uses varying/different methods. The methods which are generally used include the review from managers, interviews, situational judgment test, assessment using psychometric tools that ranges from simple to complex, i.e. the use of customized simulations in the assessment center (Church & Silzer, 2014; Silzer & Church, 2017; Deloitte, 2020; Korn Ferry, 2020). Moreover, Korn Ferry (2020), states that 13% of HR professionals surveyed reported using science-based assessment to identify HPL. With new technological developments, identifying HPL becomes possible to leverage the recording of personal data, including employee life cycles that are documented in the HR system as Big Data (Nocker & Sen, 2019; Philpot & Monahan, 2017; Kaur & Fink, 2017; Bouland-van Dam, 2020).

With regards to the HPL assessment, there have been many discussions regarding the indicators or variables that are used, as well as about the method to identify and predict HPL (Bouland-van Dam, Oostrom, de Kock, Schlechter & Jansen, 2020). However, there are limited studies that discuss how Big Data (‘employee data/track-record’) that is documented in the HR system, can contribute to identifying HPL. Generally, the data available in the HR system consists of rotation, mutation, promotion, salary (i.e., career progression), job performance, and learning development (Korn Ferry, 2020; Dries, Vantilborgh & Pepermans, 2012; Silzer & Church, 2017). Therefore, in this study, we want to find support using secondary data whether the variables Career Progression (CP), Job Performance (JP), and Learning Development (LD) can be used as indicators that affect HPL. The research was conducted at a bank that has implemented HPL in its talent management system and already has an HR System that documents the data needed for analysis.

Literature Review

Theoretical

Every employee can be improved someway, however not every individual has the potential to be an HPL. In general, an individual who is an HPL stands out from the general cohort can perform much differently than their peers (Silzer & Church, 2017), and have the individual capabilities to reach two levels higher or more than their current position (Church & Conger, 2018; Bouland-van Dam, 2020). HPL explains the degree of leadership potential of a person who can later play a role as a leader in the future, where this potential is built multidimensionally. There is no single measurement that can cover or measure everything, instead, it needs a multi-quality and multi-method approach which incorporates an employee's character and specific capabilities, knowledge, and skills (Campbell & Smith, 2014; Silzer & Church, 2017).

One of the models that are used by many companies like Citi-bank, Pepsi-co, to identify and determine HPL, is The Leadership Potential Blueprint (LPB), in which there are key elements that cover the three dimensions: foundational dimensions (personality characteristic dan cognitive capability), growth dimensions (learning ability, motivation & drive) and career dimensions (leadership competencies, functional and technical skill) (Church, 2014; Silzer & Church, 2017; Kotlyar, 2018).

The foundational dimension is a dimension that is relatively stable throughout an individual's life and in their career. Employees that are considered HPL are shown to be more intelligent, think strategically, and have interpersonal skills that are above average. From the work experience that a person has, their track record can show the roles they can take over, their problem-solving skills, and how they mitigate risks (Korn Ferry, 2020). In practice this can be observed through the recognition he or she receives from promotions, when their salary is raised, an increase in grade, etc., or known as career progression. This dimension is a traditional predictor and is the main indicator in identifying and predicting HPL (Bouland-van Dam, 2020). The Growth dimensions reflect the ability and orientation of the individual towards development. Employees who have HPL are shown by their willingness, ability to learn, and who actively participate in learning (Korn Ferry, 2020). Moreover, they possess “high learner” characters who are open to feedback and development programs and can adapt easily (Church, 2014). The practice has shown that an effective way to develop these abilities is through learning activities, training, coaching programs, and leadership development programs which are crucial for the future.

The Career dimensions are reflected in HPL competencies such as building trust, pioneering in developing teams, and technical capabilities such as operational capabilities, knowledge of business and industry, etc. This dimensional ability is formed and accumulates over time, which helps to emerge a job performance that is above-average (Church, 2014).

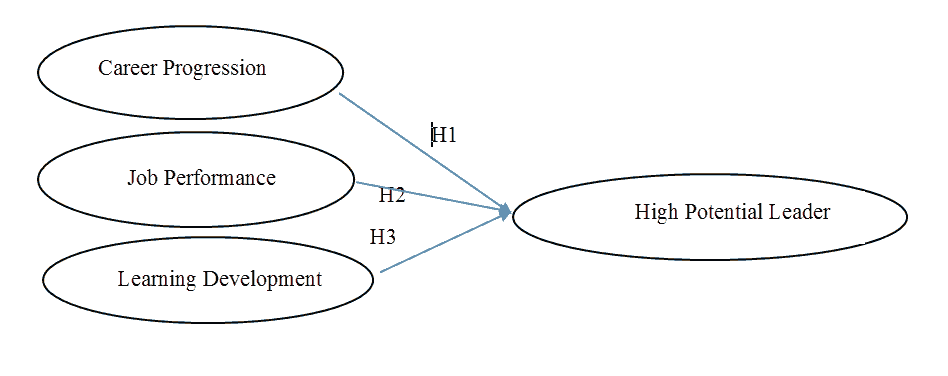

Hypotheses

Career Progression and High Potential Leadership (HPL)

A career refers to the different sequences and combinations of a person’s roles that change over a certain period (Nadarajah, 2012). Furthermore, career progression is a development of a person’s roles where there is an element of greater responsibility or wider scope. Moreover, generally, the responsibility that lies as the career progresses increases as well as an upgrade in income, promotion, or a rotation of roles in a certain company. Career progression also includes when a person leaves or transfers to another company (Kotlyar, 2018). Hence, career progression can be one of the factors to predict one’s success (Feldman, 2005). Employees are rewarded with salary increases and promotions throughout their careers as a reward for their loyalty to the company. This supports the understanding that one job to another requires certain skills and requirements (Beth & Siobhan, 2006). Employees who contribute significant value along with showcasing extra abilities are the employees that are usually promoted to a higher level above their current role. Not many employees can get to the senior level of leading the organization (Church & Conger, 2018).

Several works of literature reflect a similar understanding of career progression which includes career attainment, career experiences (Dreher & Bretz Jr, 1990), career trajectories (Browning, Thompson & Dawson, 2017), and career advancement (Socha, 2021; Feldman, 2005; Kragt & Day, 2020). An overview of a person’s career paths and experiences can provide information about their development in their abilities and capabilities as well as their strengths as the next generation (i.e., higher task potential) (Browning, Thompson & Dawson, 2017). The progress of a leader throughout his/her career will result in the gain of a series of experiences. Moreover, the career of a leader is unique because their level of leadership will be determined based on the challenges and the experience gained from handling those challenges. The core experience that a future leader can receive is the experience of building perspectives and the main challenges that the future leader has to face becomes a foundation for moving to a new, more challenging role, especially a new role as a leader (Deloitte, 2020). Research shows that career experience is the key factor that distinguishes leaders; the more important experiences that a person has, the more likely the leader will be successful in the next level position and the sooner employees can get promotions and grades (Korn Ferry, 2015; Church & Conger, 2018; Kragt & Day, 2020).

According to Silzer & Church (2013), 90% of organizations now use individual career drive as one of the predictors to identify high potential, according to the concept of performance history where previous behavior can be considered to be the best predictor of future performance in the same situation (Church & Silzer, 2014). Referring to the previous studies, in this paper we want to know the relationship between career progression and HPL, the hypothesis of this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: Career Progression (CP) has a positive relationship with HPL

Job Performance and High Potential Leadership (HPL)

Job Performance is a measurement of the achievement of an employee in meeting the targets that have been set, which utilizes both financial and non-financial indicators such as behavioral indicators (Torlak & Kuzey, 2018). Assessing a successful leader can be done in various ways, for instance, from the results of a study of 15 of 19 pieces of literature showing that the current job performance shown by an employee can be used as a criterion, and it has been found that high performers are three times more likely to be identified as HPL than low performers (De Meuse, 2017). In general, companies are still very comfortable in relying on job performance or individual performance as the main indicator in identifying one’s potential, where the performance appraisal and managerial ratings are quite large in determining HPL (Kotlyar, 2018).

However, the Corporate Leadership Council (2015) stated that current job performance cannot be reliable to predict one’s potential, because high-performing employees do not necessarily have HPL, only 30% of high-performing employees are classified as HPL (Korn Ferry, 2015). Moreover, superiors assume that potential is not the same as current or past job performance (Korn Ferry, 2020). Although showing consistency and good performance is important, it does not mean the same as showing potential as well (Church & Conger, 2018).

Referring to previous studies, in this paper we want to know the relationship between job performance and HPL, the hypothesis of this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: Job Performance (JP) has a positive relationship with HPL

Learning Development and High Potential Leadership (HPL)

Learning development refers to the increasing new knowledge and skills (competencies) which are important in determining the success of a leader. Studies have shown that if a person can learn from experience, constantly develops himself, and can play a role in important roles, they can be called an HPL (De Meuse, 2017). Learning ability is a core attribute of leadership competence (Kalnina, 2019; Korn Ferry, 2020). In learning, there is a shift from the traditional approach to a more action-based learning approach, where the appropriate competency development model is adapted to the needs to solve the problems faced today and, in the future, (Leskiw & Singh, 2007). However, it must be complemented by training in the work environment where the employee must face challenges and undergo business problem solving (Leskiw & Singh, 2007).

One of the traditional approaches is the formal training method. In general, formal training is used for leadership development in many organizations. Moreover, class training and on-the-job training are developments that also have an impact on leadership abilities. However, work experience is considered as the best learning for building leadership. Despite the latter point, there is a study that shows that formal training activities have a positive indirect relationship with leadership effectiveness and promotability (Seibert, Sargent, Kraimer, & Kiazad, 2016) While on the job training has a positive correlation with increasing the competence of a leader (Kragt & Day, 2020). The learning process can occur both in formal training and in the workplace. The more varied the roles are given in the workplace, the speed with which a person has the opportunity and experience in managing his or her members, the more likely it will be to have an impact on leadership potential. Research has shown that learning ability is very influential on potential (Dries, Vantilborgh & Peppermans, 2012; Silzer & Church, 2009) and tends to be used to identify HPL (De Meuse, 2017; Bouland-van Dam, 2020).

Leadership training tends to be more focused on short-term debriefing, where participants are expected to gain the same knowledge and skills. While the leadership development program is a more long-term debriefing. Studies show that the importance of developing leadership competencies has a positive relationship with a leader's career advancement (Kragt & Day, 2020).

Referring to the above study, the hypothesis of this paper proposes the following:

H3: Learning Development (LD) has a positive relationship with HPL

As shows in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research Model

Research Methods and Materials

Methodology

The hypotheses of this study are examined using SmartPLS. This study is research on a private bank in Indonesia which is currently ranked in the top ten with a total of +/- 7800 employees. The bank has 300 branches across the country and has implemented the concept of talent management - scheduling a talent review every year.

The data to be processed in this study are secondary data since 2016 - 2021 from the HR database which has been downloaded as of June 2021. The research focuses on Branch Manager (BM) positions with a minimum of 5 years of service at the bank. There are 206 BM in the HR data but only 132 (64%) meet the criteria. Table 1 is the profile of respondents. The CP variables are grade, position, and promotion data from 2016 - 2020, the JP variables are 2016 - 2020 performance appraisal data, the LD variables are leadership training data followed during 2016 - 2020. While the HPL dependent variable is obtained from data talent classification which has been determined by the leadership committee in H1 2021. as shows in Table 1.

| Table 1 Demographics Of Respondents |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Frequency | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 95 | 72% |

| Female | 37 | 28% |

| Age | ||

| 25 – 30 | 2 | 2% |

| 31 – 35 | 11 | 8% |

| 36 – 40 | 37 | 28% |

| 41 – 45 | 23 | 17% |

| 46 – 50 | 36 | 27% |

| 51 – 55 | 23 | 17% |

| Year of services | ||

| 5 – 10 | 76 | 58% |

| 11 – 15 | 17 | 13% |

| 16 – 20 | 9 | 7% |

| 21 – 25 | 13 | 10% |

| 26 – 30 | 10 | 8% |

| >31 | 7 | 5% |

Outer Model

In this stage, validity and reliability testing are done before evaluating the structural model. The validity test considers the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and factor loadings or outer loadings. The minimum values that must be met for AVE and outer loadings are 0.5 and 0.7 respectively (Hair et al., 2019). The discriminant validity is to ensure that each concept of each lantern variable is different from other latent variables. The model has good discriminant validity if the AVE square value of each exogenous construct (the value on the diagonal) exceeds the correlation between this construct and other constructs. The result of discriminant validity testing must be considered regarding the Fornell-Larcker criteria.

The results of data processing (Table 2) indicate that the measurement instrument is valid. The results show that the AVE value is in the range of 0.654 – 1,000. The value of factor loading or outer loadings is in the range 0.756 – 0.888. Furthermore, the reliability test refers to the results of the Composite Reliability calculation, where the results show a value of 0.850 - 1,000 and have met the requirement of 0.7 (Hair et al., 2019). Furthermore, table 2 shows that the discriminant validity test has been fulfilled where the AVE root value is greater than the correlation value between variables. as shows in Table 3.

| Table 2 Reliability And Validity Test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| AVE | CR | Outer Loading | |

| Career Progression | 0,654 | 0,850 | |

| Car_Grade | 0,888 | ||

| Car_Position | 0,776 | ||

| Car_Promotion | 0,756 | ||

| Job Performance | 1,000 | 1,000 | |

| Leadership Development | 1,000 | 1,000 | |

| Table 3 Reliability And Validity Test |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | HPL | JP | LD | |

| Career Progression | 0,809 | |||

| HPL | 0,551 | 1,000 | ||

| Job Performance | 0,459 | 0,710 | 1,000 | |

| Leadership Development | 0,172 | 0,378 | 0,484 | 1,000 |

Structural Model

Before analyzing a structural model, multicollinearity (or collinearity) should be checked to ensure that there is no bias in the regression and the aim is to determine whether the research model tends collinearity or not. The existence of collinearity will reduce the precision of the estimated coefficients, which weakens the statistical ability of the regression model. Variance inflation factor (VIF) is to measure how much collinearity is in multiple regression variables. The VIF value shows a tendency for collinearity at the maximum limit of 5.0 (Hair, Risher, Sarstedt & Ringle, 2019). Table 4 shows that the VIF value in the model is lower than 5.0, so it can be concluded that there is no collinearity.

| Table 4 Collinearity Test |

|

|---|---|

| VIF | |

| Car_Grade | 1.626 |

| Car_Position | 1.397 |

| Car_Promotion | 1.470 |

| Job Performance | 1.000 |

| Leadership Development | 1.000 |

| HPL | 1.000 |

In the structural model, the phase is to compute R2, collinearity test, and hypothesis testing. The first step before testing the hypothesis is to perform an assessment and quality model. The greater the value of R2, the better the estimation of exogenous on endogenous constructs. The R2 criteria are 0.75 (substantial), 0.50 (moderate), and 0.25 (weak) for all endogenous structures. The result of R2 is 57.1%, this shows that endogenous constructs are influenced by exogenous constructs with moderate criteria. Next, hypothesis testing is to determine whether the relationship between constructs is empirically supported or not. The statistics test results show that all hypotheses are supported except H3 indicated by the p-value < -value (=5%). Table 4 shows that H3 – which states that LD has a direct positive relationship with HPL – has a p-value of 30.5%. All path coefficients show a positive sign. From table 5 it can be concluded that the job performance variable has the most influence on high potential leaders with a path coefficient value of 0.546, after that career progression with a path coefficient value of 0.290. Meanwhile, leadership development shows the lowest path coefficient value, which is 0.064.

| Table 5 Hypothesis Test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient |

p-value | Conclusion |

| H1: CP has a direct positive relationship with HPL | 0,290 | 0,000 | Supported |

| H2: JP has a direct positive relationship with HPL | 0,546 | 0,000 | Supported |

| H3: LD has a direct positive relationship with HPL | 0,064 | 0,305 | Not Supported |

Result and Discussion

This study shows that three variables from secondary data, namely Career Progression (CP), Job Performance (JP), and Learning Development (LD) can contribute 57.1% to factors that can be used to indicate or determine whether an employee is HPL or not. The result of testing the first hypothesis (H1), which states career progression has a direct positive relationship with HPL, is supported empirically. The greater the CP, the more positive the impact in increasing HPL. This result is in line with previous studies by Church & Conger (2018); Korn Ferry (2015); Feldman (2005), which state that a person who has a positive CP tends to indicate that he or she has an HPL. Based on this explanation, it can be concluded that this study has provided support that an indication of a person who is HPL can be obtained from the track record of his career.

The result of testing the second hypothesis (H2), which states that JP has a direct positive relationship with HPL is supported empirically. The greater the job performance, the higher the HPL. The results of in-line testing with studies conducted by De Meuse (2017); Kotlyar (2018), where the higher JP tends to indicate that he is a person who has HPL. This is also under Church (2014), which stated in The Leadership Potential Blue Print (LPB), that a leader who can show consistency in his performance and who does not work alone but is certainly the result of his ability to manage and mobilize a team - in achieving the goals that have been set reflects a good leader and is an HPL. Although Korn Ferry (2020) indeed assumes that potential is not the same as current or past job performance, however, if a leader is consistent in job performance from the past to the present, it will provide opportunities for the possibility of becoming a successful HPL.

Meanwhile, the results of the third hypothesis test (H3), which stated that LD has a direct positive relationship with HPL, were not supported empirically. This is not in line with studies conducted by Kragt & Day (2020); De Meuse (2017); Bouland-van Dam (2020) which state that leadership development will affect the improvement of a leader's competence. This can be caused by the use of secondary data of learning development, where the data obtained is only learning data with a formal training method approach. This is following a study that states that formal training methods have a positive indirect relationship with effective leadership and promotability (Seibert, Sargent, Kraimer, & Kiazad, 2016). For this reason, an organization needs to be able to record a more comprehensive learning process, whether it is the implementation of learning with a traditional approach or action-based learning (Leskiw & Singh, 2007), including learning through coaching/mentoring and on the job training.

Conclusion

This study introduced a new approach to identify a High Potential Leader (HPL) using secondary data from the HR Database. Results from the hypothesis showed that 57.1% of the secondary data contributed to the identification of HPL, by which Career Progression (CP) showed a direct positive relationship against HPL, Job Performance (JP) had a positive relationship against HPL, and no relationship was found between Learning Development (LD) and HPL. Although these aforementioned results are supported and recognized with an underlying theory, there are limitations in the model that require further investigation. Since there is still 42.9% of the model that needs to be further studied other variables such as age, gender, the result of the psychiatric test, can be included as an independent or moderator variable to strengthen the result. Despite its limitations, the model is useful in enriching the literature on HPL.

References

Aguadoa, D., Andrés, J.C., García-Izquierdo, A.L., & Rodríguezc, J. (2019). LinkedIn “Big Four”: Job performance validation in the ICT sector. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 53-64.

Beth A.B., & Siobhan, O. (2006). Stretch work: Managing the career progression paradox in external labor markets. ResearchGate Journal: The Academy of Management Journal,49, 918-941.

Bouland-van Dam, S., Oostrom, J., de Kock, F., Schlechter, A., & Jansen, P. (2020). Unraveling leadership potential: Conceptual and measurement issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(2), 206-224.

Browning, L., Thompson, K., & Dawson, D. (2017). From early career researcher to research leader: survival of the fittest?. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(4), 361-377.

Campbell, M., & Smith, R. (2014). High-potential talent, a view from inside the leadership pipeline. Centre for creative leadership.

Charan, R. (2018). The high-potential leader. Jakarta: Gramedia PT Elex Media Komputindo.

Church, A.H., & Conger, J.A. (2018). So you want to be a high potential? Five X-factors for realizing the high potential’s advantage. ResearchGate Journal: People & Strategy, 41(1).

Church, A.H. (2014). What do we know about developing leadership potential?ResearchGate Journal, 46.

Church, A.H., & Silzer, R. (2014). Going behind the corporate curtain with a blueprint for leadership potential: An integrated framework for identifying high-potential talent. Research Gate Journal: People & Strategy, 36(3).

De Meuse, K. (2017). Learning agility: Its evolution as a psychological construct and its empirical relationship to leader success. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 267-295.

Deloitte. (2020). The ‘DNA’ of leadership potential.

Dreher, G.F., & Bretz Jr, R.D. (1990). Cognitive ability and career attainment: The moderating effects of early career success. Journal of Applied Psychology Research Gate, 375.

Dries, N., Vantilborgh, T., & Pepermans, R. (2012). The role of learning agility and career variety in the identification and development of high potential employees. Personnel Review, 41, 340-358.

Feldman, D. (2005). Predictors of objective and subjective career success: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 58, 367–408.

Fitz-enz, J., & Mattox, J.R. (2014). Predictive analytics for human resources. Canada: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Hair, F.J., Risher, J.J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C.M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 30, 514-538.

Kalnina, E. (2019). Learning agility as a predictor of high performance and potential: A case study from healthcare industry.

Kaur, J., & Fink, A.A. (2017). Trends and practices in talent analytics. Society for Human Resource Management and Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.

King, B. (2018). Bank 4.0. Marshall Cavendish Business.

Korn, F. (2015). Assessment of leadership potential. The research guide and technical manual.

Korn Ferry. (2020). Identifying high potential talent, the unmistakable markers that identify future-ready leaders.

Kotlyar, I. (2018). Identifying high potentials early, case study. Journal of Management Development, 37(9/10), 684-696.

Kragt, D., & Day, D.V. (2020). Predicting leadership competency development and promotion among high-potential executives: The role of leader identity. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1816.

Leskiw, S.L., & Singh, P. (2007). Leadership development: Learning from best practices. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 28, 444-464.

Marler, J.H., & Boudreau, J.W. (2017). An evidence-based review of HR Analytics. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28, 3-26.

Nadarajah, S., Kadiresan, V., Kumar, R., Kamil, N., & Yusoff, Y. (2012). The relationship of HR practices and job performance of academicians towards career development in Malaysian private higher institutions. Procedia - Social and Behavioural Sciences, 57, 102 - 118.

Nocker, M., & Sen, V. (2019). Big data and human resources management: The rise of talent analytics. 273(2019).

Philpot, S., & Monahan, K. (2017). A data-driven approach to identifying future leaders. MIT Sloan Magazine Review, 58(4), 19-22.

Rai, D. (2020). What is the difference between HR analytics, people analytics, workforce analytics and talent analytics?.

Saleh, N., & Luo, A. (2019). What's happening with potential ratings?.

Santoso, W., Sitorus, P.M., Batunanggar, S., Krisanti,, F.T., Anggadwita, G., & Alamsyah, A. (2020). Talent mapping: A strategic approach toward digitalization initiatives in the banking and financial technology (FinTech) industry in Indonesia. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 2053-4620.

Seibert, S.E., Sargent, L.D., Kraimer, M.L., & Kiazad, K. (2016). Linking developmental experiences to leader effectiveness and promotability: The mediating role of leadership self-efficacy and mentor network. Personnel Psychology, 1–41.

Shilling, M., & Celner, A. (2020). Talent: Boosting well-being and productivity through resilient leadership. 2021 Banking and Capital Markets Outlook.

Silzer, R., & Church, A.H. (2017). The pearls and perils of identifying potential. ResearchGate; Cambridge University Press (CUP).

Socha, S. (2021). An exploration of factors influencing female career progression in the United States. ProQuest Dissertations.

Torlak, N., & Kuzey, C. (2018). Leadership, job satisfaction, and performance links in private education institutes of Pakistan. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management.

Writer, S. (2019). How to use talent analytics to identify potential leaders in your organization.

Received: 23-Nov-2021, Manuscript No. asmj-21-9048; Editor assigned: 25- Nov -2021, PreQC No. asmj-21-9048 (PQ); Reviewed: 30- Nov -2021, QC No. asmj-21-9048; Revised: 11-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. asmj-21-9048 (R); Published: 07-Jan-2022.