Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

The Influencing Factors of Employee Fraud in Malaysian Financial Institution: The Application of the Fraud Pentagon Theory

Norazida Mohamed, Universiti Teknologi MARA

Nor Balkish Zakaria, Universiti Teknologi MARA

Nur Shahirah Binti Mohd Nazip, Universiti Teknologi MARA

Nor Farizal Muhamad, Universiti Teknologi MARA

Keywords

Employee Fraud, Prevention, Fraud Pentagon Theory

Abstract

Employee fraud issues are commendable of discussion in the current global economy. According to PwC (2020), 68% of fraud is committed by employees in Malaysia, and 35% of it were committed by collusion with external parties. This indicates a tighter control is required to reduce the cases. In addition, the financial institutions are known to be susceptible to fraud cases, due to its nature of directly handling a huge amount of cash. Due to the rapid changes of technological development and increased in organized crime, fraudsters focus on financial institutions as their target. Thus, the adoption of a strategic approach is required to prevent, detect and combat employee fraud occurrences. The research aim is to examine the influencing factors of employee fraud in Malaysian financial institution. The research utilise the data obtained from questionnaire that polled public attitudes regarding the influencing factors of employee fraud occurrences by adopting the Fraud Pentagon Theory. The data was analysed to evaluate and determine the perception of employees working in financial institutions on the influencing factors of employee fraud occurrences. The research suggested that elements in the Fraud Pentagon Theory, namely pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability and arrogance have significant positive influence on the employee fraud occurrences in the Malaysian financial institution.

Introduction

Employee fraud cases involving employees and top management are continuously reported in large values from all countries including Malaysia (PwC, 2016; 2018; 2020; ACFE, 2018; 2020). Employee fraud can be defined as intentional or deliberate misconduct or misappropriation of corporation’s asset by employees, from which the corporation may incur loses (Said et al., 2018). It is considered as an illegal criminal activity as it relates to abuse or false representation of position or prejudicing a person’s right to acquire personal benefit. In other words, employee fraud can be defined as a crime committed by an individual or group of employees that uses deception with an intention to gain personal advantage by evading control weaknesses. Thus, it will cause their employers financial or non-financial harm. Types of employee fraud include cases of embezzlement, ethical misconduct, misappropriation of asset and petty theft.

Survey results carried out by ACFE continuously showed that banking and financial services reported the highest number of fraud cases (ACFE, 2018; 2020). Further, it was reported in 2013 that banks incur losses in the past five years which were up to RM473.82 million due to money swindled by employees. Most employee fraud cases were involved with cash withdrawal from inactive accounts for more than three years; not crediting cash deposits into customer’s accounts; and abuse of overdraft facilities by misusing customer’s accounts (Bernama, 2013). KPMG (2019) had also reported that in 2017 and 2018, there was an increase in the number of external fraud cases in the banking and financial services, whereas the volume of employee fraud remains the same.

Even though the banking and financial industry is a regulated and controlled industry, employee fraud occurrences are still present across various financial institutions. According to Reports to the Nations by ACFE (2020), banking and financial services built the highest number of fraud cases as compared in other sectors (386 out of 1946 cases; 19.84%), with a median loss of $100,000. This is possibly due to financial institutions being characterized as fraud-fragile or more susceptible to fraud. The magnitude of impact brought by occurrences of fraud in financial institutions is considerably higher than those occurring in other sectors due to the nature of industry which involves managing large amount of money (Awang & Ismail, 2018).

However, potential detrimental impact caused by employee fraud in the financial institution can be greater than those caused by external fraud, due to employees’ ability to exploit the control weaknesses in order to commit fraud and acquire monetary gain. Further in the report, it was also stated that challenges faced by banks today include (1) cyber and data breaches, (2) social engineering, (3) faster payments, (4) evolving digital channels and (5) open banking. Accordingly, it seems that today’s fraudsters know how to take advantage of technology. Hence, fraud becomes more sophisticated, especially when the economic environment is susceptible to fraud.

According to Sorunke (2016); Vousinas (2019), there are several sophisticated fraud models which follow the development of fraud occurrences. These fraud models provided unique perspectives of fraud which are beyond the basics of Fraud Triangle Theory. Fraud Triangle Theory was developed by Donald Cressey (1953), a criminologist whose research was focused on embezzlers or trust violators. He claimed that there are three major elements of fraud which are pressure, opportunity, and rationalisation.

Modification of Fraud Diamond Theory was introduced by Wolfe & Hermanson (2004) with an additional element of capability. Past researchers mentioned that the Fraud Triangle Theory was unable to solve fraud issues which were due to both elements of pressure and rationalization elements as they are difficult to be observed (Gbegi & Adebisi, 2013; Sorunke, 2016; Vousinas, 2019). The existence of capability refers to personal characteristics and skills of perpetrators which play important role in ensuring that fraud takes place in light of the presence of pressure, opportunity and rationalisation. Occurrences of fraud, especially the multibillion-dollar fraud scandals, would not have existed without having the right person with the right skills to execute the manipulation of information. Nevertheless, Fraud Diamond Theory also has its shortcomings as the model is insufficient to explain perpetrators’ motivation in committing fraud. According to Sorunke (2016); Marks (2018), this could be due to behavioural and environmental elements of fraudsters which were isolated from the two theories.

Realising this gap, Fraud Pentagon Theory (FPT) was introduced by Horwath (2011) that consists five (5) elements of pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability and arrogance. Arrogance is found to be a new element in Fraud Pentagon Theory. Arrogance refers to the lack of conscience, which is an act of dominance and entitlement or greed by a person who believes that corporate policies and procedures does not apply to him or her. The study by Marks (2018) motivates researches to include arrogance as one of the influencing factors towards employee fraud in Malaysia. Findings of his research indicated that 70 per cent of fraudsters are profiled in tandem with pressure and arrogance, or greed.

This paper aims to investigate the influencing factors of employee fraud in Malaysian financial institutions based on FPT perspectives. The remainder of this paper is divided into few different sections, beginning with the literature review right after this introduction. The methodology section will then be discussed and followed by the findings and discussion. The last section concludes the overall paper.

Literature Review And Hypothesis Development

Fraud Pentagon Theory provides useful framework for organisations to analyse their vulnerability towards fraud and identify possible unethical behaviour that might be committed by employees.

Cressey (1953) concluded that a person will commit fraud when the three factors of (1) perceived pressure; (2) perceived opportunity; and (3) rationalisation exist within the conscience of the person. Perceived opportunity arise when fraudsters find ways to use their position, or when there is lack of internal controls and monitoring, to commit fraud. This comes with a realisation that they are unlikely to be caught (Kassem & Higson, 2012). The Fraud Triangle Theory suggests that certain factors will increase the risk of fraud to occur, however it does not provide a perfect guidance with respect to this current era. This is because the model itself is nearly half a century old, and there has been considerable social changes observed throughout the years (Vousinas, 2019). In addition to that, Sorunke (2016), also Kassem & Higson (2012) argued that this model can no longer explain on fraud motives that are relevant to today’s business environment, as the pressure and rationalization elements becomes more difficult to be observed.

Fraud Diamond Theory was introduced by Wolfe & Hermanson (2004) as an extended version of Fraud Triangle Theory (Cressey, 1953). Kassem & Higson (2012) claimed that many fraud cases would not have occurred if fraudsters were unable to carry out the crime. It was argued that an individual’s personality traits and capability would have an impact towards the likelihood of fraud occurrences. Fraud Pentagon Theory was introduced by Jonathan Marks in 2010. This theory is an expansion from Fraud Diamond Theory (2004). Arrogance is an attitude of superiority and entitlement, or greed within a person who believes that internal controls simply does not apply to him or her (Horwath, 2011). Integrating this element into Fraud Triangle, this theory evolves into Fraud Pentagon Theory with five elements of: (1) Pressure; (2) Opportunity; (3) Rationalization; (4) Capability and (5) Arrogance. This theory considers all factors which are necessary for fraudulent activities to occur.

Overview of Fraud and Employee Fraud

The issue of fraud, particularly with regards to the current economy, is highly commendable of debate as many reports and past researchers have highlighted this issue (AFCE, 2020; PwC, 2020; Said et al., 2017; Kazemian, Nia & Vakilifard, 2019). Occupational fraud on the other hand is known as “the use of one’s occupation for personal enrichment through deliberate misuse or misapplication of the employing organisation’s resources or assets.” (ACFE, 2014). It generally deliberates misconduct by employees through which the organisation is to incur losses from the said misconduct. Fraud can be committed by any employee at any level within the organisation, where they would have strong understanding of the business and have the power to override control (Deloitte & Touche, 2010; World Bank, 2017).

Dadzie-Dennis, Ghansah & Korletey (2018) classified occupational fraud into management fraud and employee fraud as it also involves the distortion of earnings reported in financial statements which are prepared for stakeholders (Mohamed & Handley-Schachler, 2014). Such fraud may have impact on share prices, management bonuses and debt financing availability and terms.

Whereas, Dadzie-Dennis, et al., (2018) also stated that employee fraud involves non-senior employees that involves with, but not limited to, embezzlement, petty theft, asset misappropriation, bribery, corruption, and computer fraud. They also added that no institution or corporation is immune to employee fraud. Employee fraud can take place in many forms and at all levels of associate within the company. Employees mainly aim for functions and departments that are highly involved with money and asset transactions of significant values, usually in the purchasing and procurement departments (Nawawi & Salin, 2018). According to Peters & Maniam (2016), such fraud may also involve an employee claiming excess overtime on their payroll documentation which is more than what was physically worked on; or an employee who takes products from the company without paying or being authorized to do so in order to gain personal advantage; or an employee who takes money from company accounts without anyone’s knowledge and depositing them into his/her personal account; or many other forms that may illegally benefit the employee and give losses to the company.

Fraud activities cost greatly to the company, for which it can cause business failure, especially for small companies, as they would not have enough resources to cover for their losses (Nawawi & Salin, 2018). Employee fraud may cause both internal and external issues to businesses. Internally, it may bring impact towards the operations, opportunity cost of missing sales, stock losses and low employee morale (Omar et al., 2016). Externally, if employee fraud is made known to the public, it will cause a restriction of investors’ confidence and the financial market stability; loss of public image and credibility; worsens business relations and dealings with corporate partners; as well as a risk of legal action, and ultimately businesses may result in winding up (Said et al, 2016; Nawawi & Salin, 2018).

Employee Fraud in the Financial Institution

Suh, Nicolaides & Trafford (2019) posited that internal vulnerabilities of banking and financial industry has been proven to be caused by several global examples. For instance, Suh, et al., (2019) had reported that 361 cases of employee fraud were found in Korean commercial banks, insurance firms and financial companies during a five-year period from 2010 to 2014. In France, a trader at the Société Générale, Jerome Kerviel, incurred a massive loss of around £4 billion and was found guilty of forgery, unauthorised computer usage and breach of trust (BBC News, 2010) (as cited in Suh et al., 2019). Hence, globally, employee fraud in the financial institutions is one of the most critical causes in the major banking crises. According to Sanusi et al., (2015); Bonsu, Dui & Muyun (2018), fraud in financial institution is diversified, as it may range from employee fraud to consumer fraud; from corporate fraud to individual fraud; and from accounting fraud to transactional fraud.

Employee fraud in financial institutions include theft of cash from bank tills, forged customers’ signatures to withdraw money from their account, overtime claims for non-worked hours, opening and operating fictitious accounts and transfer funds illegally to another account, and computer fraud through the compromise of an e-banking user’s log-in credentials (Akinyomi, 2012; Kingsley 2012). Bhasin (2015) stated that most banking and financial institutions would normally experience fraud when safeguards and procedural controls are ineffective. In addition, Sanusi, et al., (2015), as well as Kolapo & Olaniyan (2018) also specified that poor internal control system and weak corporate governance are among the factors leading to fraud as it creates an environment for employees to act fraudulently.

Losing public confidence in the financial system could contribute to significant economic and public welfare issues. Moreover, the financial market, capital structure, efficient market hypothesis and credit ratings can be dramatically impacted by fraud and irregularities in the financial institution (Awang & Ismail, 2018; Awang, 2019). The efficiency of intermediation process will decrease if the financial system becomes dysfunctional.

Hypotheses Development

Pressure faced by managers or employees may lead them to commit misconduct or fraud as an easy way to eliminate their problems. A number of researchers have found that there is a significant relationship between pressure and employee fraud occurrences (Aghghaleh & Mohamed, 2014; Purnamasari & Oktaroza, 2015; Kazemian et al., 2019).

In an environment that imposes excessive pressure on employees, even honest employees would be capable to commit fraud. The larger the incentive or pressure, the greater will be the possibility of an employee to commit fraud. Examples of pressures that might trigger employees to commit fraud may include personal financial loss, greed, living beyond one’s means, personal debt, and unexpected financial needs (Albrecht, Albrecht & Albrecht, 2008;

Kassem & Higson, 2012). Thus, it can be stated that employees who have pressure would be more driven than other employees who do not have pressure to commit fraud.

Further, financial pressure plays a crucial role in raising the risk of fraud among employees in financial institution. Nevertheless, depending on the employee’s position, the financial pressure may appear differently (Said et al., 2017). Financial pressure may typically act as a motivation for cashiers or those in lower positions, however managers’ financial situation may be threatened by the firm’s financial performance when they have a significant financial stake in the company (Skousen et al., 2009). Kazemian, et al., (2019) added that under a context of the banking and financial industry, pressure to misappropriate assets could arise during periods of financial instability, where there are obligations to fulfill third parties’ financial expectations and coercion by the entity’s financial performance. Therefore,

H1: Pressure has positive influence on the occurrences of employee fraud

Opportunities are often associated with instances where there is no surveillance or monitoring system, or when they identify weaknesses within internal controls of the organization. This provides a chance for employees to act fraudulently to obtain personal gain (Albrecht et al., 2008; Kassem & Higson, 2012; Dellaportas, 2013).

Further, poor corporate governance provides opportunities for management to engage with employee fraud. It is usually associated with weak internal control and inadequate monitoring system. This is supported by Rae & Subramaniam (2008); Said, et al., (2017), where they claimed that poor system control, inadequate oversight, lack of segregation of duties or lack of management approval creates an opportunity for fraud to occur among employees. Thus, the existence of opportunity may inevitably contribute to the intention that drives or causes a person to commit fraud.

In addition, Suh, et al., (2019) argued that “pressure” and “rationalization” elements in fraud theories are namely non-shareable financial problem, whereby the elements are not transparently assailable for organisations to prevent the fraud from occurring. This thus makes eliminating opportunities as a critical focus for the organisations. At this juncture, it can be deduced that if opportunities are effectively reduced, fraud occurrences can also be prevented, thus a positive relationship between opportunity and fraud occurrences exists. Several prior empirical studies have confirmed the significant positive association between the elements of opportunity and fraud occurrences, such as those by Chen & Elder (2007); Purnamasari & Oktaroza (2015); Said, et al., (2017); Kazemian, et al., (2019). Therefore,

H2: Opportunity has positive influence on the occurrences of employee fraud

Rationalization happens through a person’s tendency to reinterpret his or her injustice and misconduct as socially accepted actions and it is one of the major elements that contribute to fraud occurrences (Tsang, 2002; Kula, Yilmaz & Kaynar, 2011). Another instance, according to Zikmund & Janosek (2014), bank employees often convince themselves that they are merely borrowing from the bank. Some have also rationalized that their crime is due to underpayment. Some also justify that they are not stealing but only borrowing from the company.

In addition, Said, et al., (2017) indicated that in PwC’s 2011 global economic crimes survey, 12 per cent of participants claimed that the fraudsters’ rationale to make excuses for their misconduct are the greatest risk of fraud. For instance, Ghafoor, Zainudin & Mahdzan (2019) mentioned that prior violations and changes of auditor, which were used to test the rationalization element, contributes to the occurrence of fraud. Further, Kazemian, et al., (2019) mentioned that a research by Nelson, Elliot, Tarpley in 2002 had investigated several fraud cases and the impact of employee fraud on various business industries, including the banking and financial industry, concluded that rationalization allows fraudsters to continually assume that they remain honest and trustworthy. Thus, the tendency to commit fraud will increase when rationalization is present in the working environment. Therefore,

H3: Rationalization has positive influence on the occurrences of employee fraud

Researchers have widespread belief that the Fraud Triangle Theory can be further strengthened by adding a fourth dimension, being the capability element, in order to improve fraud prevention and detection in organisations (Kassem & Higson, 2012; Dorminey et al., 2012; Gbegi & Adebisi, 2013; Vassiljev & Alver, 2016; Vousinas, 2019).

Kassem & Higson (2012) argued that in order for fraud to occur, the fraudster must possess the capabilities to take advantage of the opportunity available to them. Capability refers to the person’s position or function within the organisation that can enable them to exploit a fraud opportunity that is unavailable to others. Moreover, successful fraudsters will have enough knowledge to recognize and manipulate the vulnerabilities in the internal control system by taking advantage of their position, function or authorized access. The capability element can be divided into six important traits for fraud occurrences which are position, intelligence, ego, coercion, deceit and stress management (Murphy, Free & Branston, 2011). Further, as mentioned by Kazemian, et al., (2019), several fraud cases in recent years have been committed by smart, knowledgeable and experienced fraudsters who have good knowledge of the control of the organisation. Therefore,

H4: Capability has positive influence on the occurrences of employee fraud.

Vousinas (2019) suggests that narcissistic people are more likely to commit fraud due to their greed for entitlement, desire for dominance and protecting their pride, which are important drivers of fraud. A person that is often self-absorbed, self-confident and an arrogant egotist, who is motivated to excel at all costs, are the characters characterizing those who commit fraud. Thus, according to the Fraud Pentagon Theory, the crime or illegal act is the product of mental manipulation of an individual, which helps to fuel the feeling of dominance or influence over others.

Geis (2011) argued that a person that is arrogant is more likely to act fraudulently as compared to a person who is submissive. Chen & Elder (2013); Said, et al., (2017) posited that employees who have lack ethical values will tend to ignore policies and procedures in order to pursue their own interests and may conduct fraud. Thus, unethical actions and behaviour will more likely be committed by less ethical employees who are arrogant or greedy. Therefore,

H5: Arrogance has positive influence on the occurrences of employee fraud

Methodology

This current research adopted a survey research where the target population of this research are employees working in financial institutions in Malaysia. Thus, in order to obtain a meaningful result that could represent the industry as a whole, employees of financial services institution were chosen as individuals of the unit analysis. According to Annual Economic Survey 2018 for the reference year 2017, the total population of the study that comprises of all employees working in the financial service institutions are 357,993 individuals’

This research uses purposive judgement sampling techniques to gather data. It is considered appropriate based on the capacity of respondents to provide information that fits the purpose of this research (Mohd-Sanusi, Rameli & Omar, 2015). Respondents are arbitrarily selected for their unique characteristics or experiences, attitudes or perceptions specifically employees in Malaysian financial institution to represent the industry.

Green (1991) suggested the sample size model N>50+8m, where m refers to the number of Independent Variables (IVs). Since this research has five IVs, the minimum sample size should be 90 in order to represent the population of employees in the Malaysian financial institutions. The minimum sample size, which is 90 samples, aligns with Roscoe (1975), where a sample size between 30 to 500 is appropriate for most research (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). The total number of respondents who have answered the questionnaire for the current research is 130 respondents. This concludes that there is sufficient sample size to conduct multiple regression analysis for this research. Thus, Google Forms survey was structured and distributed from early March to end of April 2020.

The questionnaire design consists of seven (7) sections. For section A, it is aimed to isolate the specific pertinent demographic information that can be used in the research. Section B seeks respondents’ perception on employee fraud occurrences in organisations. Section C to G solicits respondents’ opinion on each of the influencing factors of employee fraud, that consists of pressure, opportunity, rationalisation, capability, and arrogance. Each of the elements were gauged from the Fraud Pentagon Theory. Respondents were asked to express their opinion on the influencing factors of employee fraud on a six-point Likert-scale, ranging from 1 – strongly disagree, 2 – disagree, 3 – slightly disagree, 4 – slightly agree, 5 – agree to 6 – strongly agree.

Findings and Discussion

Demographic Information

Demographic profiles of the 130 respondents were evaluated based on the following criteria: gender, age, marital status, highest academic qualification, position in the institution and the length of experience in current branch.

Results and Discussion

| Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of the Respondents' Demographic |

||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Frequency (N=104) | Percentage (%) |

| Male | 53 | 40.8 |

| Female | 77 | 59.2 |

| Age | ||

| Less than 25 years old | 7 | 5.4 |

| 25-30 | 53 | 40.8 |

| 31-40 | 35 | 26.9 |

| 41-50 | 27 | 20.8 |

| 51 years old and above | 8 | 6.2 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 47 | 36.2 |

| Married | 72 | 55.4 |

| Divorced | 6 | 4.6 |

| Widowed | 5 | 3.8 |

| Academic Qualification | ||

| SPM/Certification | 4 | 3.1 |

| Professional | 9 | 6.9 |

| Diploma | 16 | 12.3 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 76 | 58.5 |

| Master Degree | 21 | 16.2 |

| Doctor of Philosophy | 4 | 3.1 |

| Current Position | ||

| Top Management | 11 | 8.5 |

| Middle Management | 65 | 50 |

| Supervisor | 18 | 13.1 |

| Support Staff | 36 | 28.5 |

| Work Experience | ||

| Less than 1 year | 16 | 12.3 |

| 1 to 3 years | 38 | 29.2 |

| 4 to 5 years | 17 | 13.1 |

| 5 years and above | 59 | 45.4 |

Table 1 depicts the descriptive statistics for respondents’ gender. Based on the analysis, 59.2 per cent of the respondents were female respondents, whereas 40.8 per cent were male respondents. The results showed that the largest group of respondents was in the category of 25 to 30 years’ old, which constitutes 40.8 per cent of respondents, indicating almost half of the overall total respondents. The second largest group is at the range of 31 to 40 years old with 26.9 per cent, while the next category ranged from 41 to 50 years old with 20.6 per cent. There were only 6.1 per cent of respondents in the category of 51 years old and above, while respondents less than 25 years old become the smallest group with only a percentage of 5.3. The result indicated that the majority of respondents falls into the 25 to 30 years old age category. 55.4 per cent of the respondents are married, meanwhile 36.2 per cent are single. the highest percentage is from employees holding a Bachelor’s Degree with 58.5%, followed by employees with Master’s Degree at 16.2% and employees with Professional Certificate at 6.9%. Employees with SPM/Certification and doctorate degree both hold 3.1% of the overall respondents

Half of the respondents are in the middle management and professional position (50%) while the second highest number of respondents came from support staff, which is 28.5 per cent. 13.1 percent represents supervisors and the remaining 8.5 per cent represents employees in the top management. Results indicated that respondents would possess adequate knowledge and experience in employee fraud in the financial institution, and thus, can provide reliable information for the purpose of this research. Majority of the respondents has worked in their current institution for 5 years and above (45.4%). 29.2 per cent of the respondents had worked for 1 to 3 years and 13.1 per cent of respondents has worked between 4 to 5 years while the remaining 12.3 per cent% of respondents have worked less than 1 year in their current institution.

For reliability of the results, Cronbach’s Alpha values for Employee Fraud show excellent internal consistency and reliability for its items with a value of 0.907. Whereas Pressure, Rationalization, Capability and Arrogance indicates good internal consistency and reliability for their items, with values of 0.885, 0.867, 0.851 and 0.885, respectively. Meanwhile, Opportunity was indicated to have acceptable internal consistency and has reliable items with a value of 0.724. Overall, the value of Cronbach’s Alpha for all constructs indicated that the statements used for questionnaire are reliable and acceptable in measuring the perception of respondents on each element.

Based on the results from skewness and kurtosis tests, the values obtained were between -2 to +2, thus the collected data were assumed to be normally distributed.

| Table 2 Correlation Analysis |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | EF | P | O | R | C | A | |

| Employee Fraud | 1 | ||||||

| Pressure | Pearson Correlation | 0.626 | 1 | ||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0 | ||||||

| Opportunity | Pearson Correlation | 0.685 | 0.564 | 1 | |||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.013 | 0.001 | |||||

| Rationalization | Pearson Correlation | 0.581 | 0.418 | 0.459 | 1 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Capability | Pearson Correlation | 0.546 | 0.277 | 0.368 | 0.475 | 1 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0 | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Arrogance | Pearson Correlation | 0.574 | 0.682 | 0.468 | 0.415 | 0.162 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.035 | 0.207 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.066 | ||

In addition, Table 2 also shows the correlation between IVs. According to Pallant (2011), a variable is indicated to be not independent and should be omitted if there are two IVs that are highly correlated (r>0.9). This is to avoid multicollinearity issues which would violate the multiple regression assumption. The results depicted in Table 2 indicated that all IVs do not violate the multicollinearity assumption as all r values are below 0.9. The interpretation of results is as follows:

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

To explain on the results for regression analysis, there are three tables that need to be referred to, which are regression analysis model summary table, regression analysis of variance (ANOVA) and regression analysis of variance (coefficient) tables.

| Table 3 Regression Analysis Model Summary |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | R | R-Squared | Adjusted R-Squared |

Std. Error of the Estimate | |

| 1 | 0.825 | 0.68 | 0.668 | 0.82287 | |

| Model | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Regression | 178.811 | 5 | 35.762 | 52.815 | 0 |

| Residual | 83.963 | 124 | 0.677 | ||

| Total | 262.774 | 129 | |||

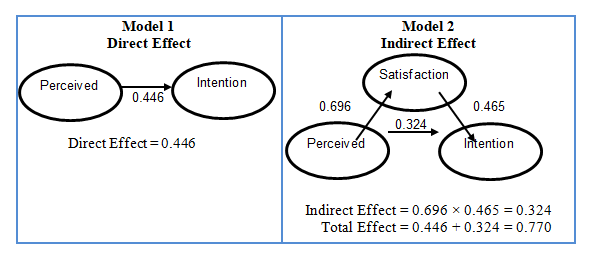

Table 3 depicts the R-squared value for the regression model. An R-squared value of 0.680 indicated that the five IVs, namely, pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability and arrogance, are able to explain 68.0% of the occurrences of employee fraud in Malaysian financial institutions. Meanwhile, the remaining 32% of the changes is affected by other factors that are not considered in the current research. Table 4.3 also showed that the overall multiple regression of equation model is significant (F(5,124)=52.815, p=0.000). This indicated that at least one of the IVs had significant linear relationship with the occurrences of employee fraud.

| Table 4 Multiple Regression Analysis of Variance (Coefficient) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Standard Error | t | Sig. | |

| Constant | -4.386 | 0.259 | -7.953 | 0 |

| Pressure | 0.316 | 0.076 | 2.183 | 0.031 |

| Opportunity | 0.536 | 0.038 | 4.998 | 0 |

| Rationalization | 0.278 | 0.07 | 2.266 | 0.025 |

| Capability | 0.524 | 0.071 | 4.671 | 0 |

| Arrogance | 0.296 | 0.043 | 2.821 | 0.006 |

Table 4 describes the multiple regression analysis conducted on the five IVs and the single DV. It predicted the influencing factor of employee fraud in Malaysian financial institutions to be equal to the following equation:

The equation showed that when there is no pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability, and arrogance, employee fraud occurrences would decrease by 4.386 units. The result also shows that, holding other variables constant, for each one unit increase of pressure, the occurrences of employee fraud may increase by 0.316 units; for each one unit increase of opportunity, the occurrences of employee fraud may increase by 0.536 units; for each one unit increase of rationalization, the occurrences of employee fraud may increase by 0.278 units; for each one unit increase of capability, the occurrences of employee fraud may increase by 0.524 units; and for each one unit increase of arrogance, the occurrences of employee fraud may increase by 0.296 units. Hence, the results showed that all IVs have positive linear relationships with the occurrences of employee fraud.

On top of that, Table 5 also shows the significance between each IVs and DV. The results showed that there is a significant positive linear relationship between pressure and the occurrences of employee fraud (t(124)=2.183, p=0.031). There is a significant positive linear relationship between opportunity and the occurrences of employee fraud (t(124)=4.998, p=0.000). There is a significant positive linear relationship between rationalization and the occurrences of employee fraud (t(124)=2.266, p=0.025). There is a significant linear positive relationship between capability and the occurrences of employee fraud (t(124)=4.671, p=0.000); and lastly there is a significant positive linear relationship between arrogance and the occurrences of employee fraud (t(124)=2.821, p=0.006). Hence, results showed that all IVs have significant positive relationship with the occurrences of employee fraud.

| Table 5 Summary Of Hypothesis Testing |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Hypotheses | Significance Level | Result | |

| H1 | Pressure (P) | There is a significant positive relationship between P and EF. | 0.031 | Accepted |

| H2 | Opportunity (O) | There is a significant positive relationship between O and EF. | 0 | Accepted |

| H3 | Rationalization (R) | There is a significant positive relationship between R and EF. | 0.025 | Accepted |

| H4 | Capability (C) | There is a significant positive relationship between C and EF. | 0 | Accepted |

| H5 | Arrogance (A) | There is a significant positive relationship between A and EF. | 0.006 | Accepted |

Conclusion

The aim of this research is to study how the element of the Fraud Pentagon Theory to influence the occurrences of employee fraud in Malaysian financial institutions. Findings from the current study had revealed that for the first objective, the pressure element have significant positive influence over occurrences of employee fraud in Malaysian financial institutions. For the second objective, there was also a significant positive influence between opportunity and employee fraud occurrences in Malaysian financial institutions. The third objective indicated that there is a significant positive influence between rationalization and employee fraud occurrences in Malaysian financial institutions. Next, the fourth objective had also indicated that capability have significant influence over employee fraud occurrences in Malaysian financial institutions. Lastly, the fifth objective indicated that arrogance have significant influence on employee fraud occurrences in Malaysian financial institutions.

Overall, the findings from the current study showed that pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability and arrogance had significantly influence employee fraud occurrences in Malaysian financial institutions. Findings from the current research have proven that all the elements of the Fraud Pentagon Theory have significant impacts on the occurrences of employee fraud.

Acknowledgement

This paper would like to acknowledge Accounting Research Institute of Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia for helping the overall conduct of this research.

References

- Aghghaleh, S.F., & Mohamed, Z.M. (2014). Fraud risk factors of fraud triangle and the likelihood of fraud occurrence: Evidence from Malaysia. Information Management and Business Review, 6(1), 1-7.

- Akinyomi, O.J. (2012). Examination of fraud in the Nigerian banking sector and its prevention. Asian Journal of Management Research, 3(1), 182-194.

- Albrecht, W.S., Albrecht, C., & Albrecht, C.C. (2008). ‘Current trends in fraud and its detection. Information Security Journal: A Global Perspective, 17(1), 2-12.

- Awang, Y., & Ismail, S. (2018). Determinants of financial reporting fraud intention among accounting practitioners in the banking sector: Malaysian evidence. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 34(1), 32-54.

- Awang, Y. (2019). The influences of attitude, subjective norm and adherence to Islamic professional ethics on fraud intention in financial reporting. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 10(5), 710-725.

- Bernama, (2013). Hundreds of millions swindled from banks in past 5 years, mostly by employee, say police, Retrieved from www.themalaysianinsider.com.

- Bhasin, M.L. (2015). An empirical study of frauds in the banks. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 4(7).

- Bonsu, O.A.M., Dui, L.K., Muyun, Z., Asare, E.K., & Amankwaa, I.A. (2018). Corporate fraud: Causes, effects, and deterrence on financial institutions in Ghana. European Scientific Journal, 14(28), 315-335.

- Chen, K.Y., & Elder, R.J. (2007). Fraud risk factors and the likelihood of fraudulent financial reporting: Evidence from statement on Auditing Standards No. 43 in Taiwan. Syracuse University Whitman School of Management Syracuse.

- Cressey, D.R. (1953). Other people’s money: The social psychology of embezzlement. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Dadzie-Dennis, E.N., Ghansah, K., & Korletey, J.T., (2018). Employee fraud in the banking sector of ghana. SBS Journal of Applied Business Research, 4.

- Dellaportas, S. (2013). Conversations with inmate accountants: Motivation, opportunity and the fraud triangle. Accounting fórum, 37(1), 29-39.

- Deloitte, & Touche. (2010). Public sector Fraud: Identifying the risk areas.

- Dorminey, J., Fleming, A.S., Kranacher, M.J., & Riley, R.A. (2012). The evolution of fraud theory. Issues in Accounting Education, 27(2), 555-579.

- Geis, G. (2011). White-collar and corporate crime: A documentary and reference guide. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA.

- Ghafoor, A., Zainudin, R., & Mahdzan, N.S. (2019). Factors eliciting corporate fraud in emerging markets: Case of firms subject to enforcement actions in Malaysia. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(2), 587-608.

- Green, S.B. (1991). How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis? Multivariate Behavioral Research, 26, 499?510.

- Horwath, C. (2011). Putting the freud in fraud: Why the fraud triangle is no longer enough. IN Horwath: Crowe.

- Kassem, R., & Higson, A. (2012). The new fraud triangle model. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences, 3(3), 191-195.

- Kazemian, S., Said, J., Nia, E.H., & Vakilifard, H. (2019). Examining fraud risk factors on asset misappropriation: evidence from the Iranian banking industry. Journal of Financial Crime, 26(2), 447-463.

- Kingsley, E. (2012). Predictive asset management. In SPE Intelligent Energy International. Society of Petroleum Engineers. Texas, USA: Richardson.

- Kolapo, F.T., & Olaniyan, T.O. (2018). The impact of fraud on the performance of deposit money banks in Nigeria. International Journal of Innovative Finance and Economics Research, 1(6), 40-49.

- KPMG International. (2006). Financial statement fraud and fraud risk management, KPMG Forensic Malaysia.

- KPMG International. (2019). The multi-faceted threat of fraud: Are banks up to the challenge? Global Banking Fraud Survey. KPMG International.

- Kula, V., Yilmaz, C., Kaynar, B., & Ali, R. (2011). Managerial assessment of employee fraud risk factors relating to misstatements arising from misappropriation of assets: A survey of ISE companies. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(23), 171-179.

- Marks, J. (2018). Fraud pentagon – An enhancement to the three elements of fraud. Elements Discussion Leader: Crowe Horwarth. Crowe Horwarth.

- Mohamed, N., & Handley-Schachelor, M. (2014). Financial statement fraud risk mechanisms and strategies: The case studies of Malaysian commercial companies. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 145, 321-329.

- Mohd-Sanusi, Z., Rameli, M.N.F., Omar, N., & Ozawa, M. (2015). Governance mechanisms in the Malaysian Banking Sector: Mitigation of fraud occurrence. Asian Journal of Criminology, 10(3), 231-249.

- Murphy, P.R., Free, C., & Branston, C. (2011). Organizational culture as a predictor of fraud. Queen’s School of Business. Queen’s University.

- Nawawi, A., & Salin, A.S.A.P. (2018). Internal control and employees’ occupational fraud on expenditure claims. Journal of Financial Crime, 25(3), 891-906.

- Nawawi, A., & Salin, A.S.A.P. (2018). Employee fraud and misconduct: Empirical evidence from a telecommunication company. Information & Computer Security, 26(1), 129-144

- Omar, M., Nawawi, A., & Puteh Salin, A.S.A. (2016). The causes, impact and prevention of employee fraud: A case study of an automotive company. Journal of Financial Crime, 23(4), 1012-1027.

- Pallant, J. (2011). Survival manual. A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS.

- Peters, S., & Maniam, B. (2016). Corporate fraud and employee theft: Impacts and costs on business. Journal of Business and Behavioral Sciences, 28(2), 104.

- Purnamasari, P., & Oktaroza, M.L. (2015). Influence of employee fraud on asset misappropriation analysed by fraud diamond dimension.

- Rae, K., & Subramaniam, N. (2008). Quality of internal control procedures. Managerial Auditing Journal.

- Rafidi, M., Said, J., Kazemian, S. & Zakaria, N.B. (2016). Enhancing banking performance through holistic risk management: The comprehensive study of disclosure approach. Management & Accounting Review (MAR), 15(1), 315-339.

- Roscoe, J.T. (1975). Fundamentals research statistics for behavioural sciences. “What sample size is enough? in internet survey research”. Interpersonal Computing and Technology: An electronic Journal for the 21st Century.

- Said, J., Alam, M., Ramli, M., & Rafidi, M. (2017). Integrating ethical values into fraud triangle theory in assessing employee fraud: Evidence from the Malaysian banking industry. Journal of International Studies, 10(2), 170-184.

- Sanusi, Z.M., Rameli, M.N.F., & Isa, Y.M. (2015). Fraud schemes in the banking institutions: Prevention measures to avoid severe financial loss. Procedia Economics and Finance, 28, 107-113.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons.

- Skousen, C.J., Smith, K.R., & Wright, C.J. (2009). Detecting and predicting financial statement fraud: The effectiveness of the fraud triangle and SAS No. 99. Advances in Financial Economics, 13(1), 53-81.

- Sorunke, O.A. (2016). Personal ethics and fraudster motivation: The missing link in fraud triangle and fraud diamond theories. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 6(2), 159-165.

- Suh, J.B., Nicolaides, R., & Trafford, R. (2019). The effects of reducing opportunity and fraud risk factors on the occurrence of occupational fraud in financial institutions. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 56, 79-88.

- Tsang, J.A. (2002). Moral rationalization and the integration of situational factors and psychological processes in immoral behavior. Review of General Psychology, 6(1), 25-50.

- UK Fraud Act 2006. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/35.

- Vassiljev, M., & Alver, L. (2016). Conception and periodisation of fraud models: Theoretical review. In 5th International Conference on Accounting, Auditing, and Taxation (ICAAT 2016). Atlantis Press.

- Vousinas, G.L. (2019). Advancing theory of fraud: The S.C.O.R.E. Model. Journal of Financial Crime, 26(1), 372-381.

- Wilson, R.A. (2004). Employee dishonesty: National survey of risk managers on crime. Journal of Economic Crime Management, 2(1), 1-25.

- Wolfe, D.T., & Hermanson, D.R. (2004). The fraud diamond: Considering the four elements of fraud. The CPA Journal, 74(12), 38-42.

- World Bank. (2017). Public sector internal audit: Focus on fraud. Centre for Financial Reporting Reform, United States.

- Zikmund, A., & Janosek, M. (2014, May). Calibration procedure for triaxial magnetometers without a compensating system or moving parts. In Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC) Proceedings, 2014 IEEE International.