Research Article: 2018 Vol: 17 Issue: 6

The Knowledge-Based Economy and Innovation Policy in Kazakhstan: Looking at Key Practical Problems

Meiramkul Saiymova, K. Zhubanov Aktobe Regional State University

Sholpan Smagulova, Kazakh Economic University

Raushan Yesbergen, K. Zhubanov Aktobe Regional State University

Gulnaz Demeuova, K. Zhubanov Aktobe Regional State University

Botagoz Bolatova, K. Zhubanov Aktobe Regional State University

Bagdagul Taskarina, K. Zhubanov Aktobe Regional State University

Almagul Ibrasheva, K. Zhubanov Aktobe Regional State University

Abstract

Since gaining independence, Kazakhstan has been experiencing internal and external economic crises due to the nature of its economy, which relies on the oil and gas sector. To transform and drive national economic development, Kazakhstan has adopted policies and several strategic documents that aim to boost innovation activities and growth of nanotechnology sector, particularly in the industrial sector. This paper aims to review and analyse the national innovation and nanotechnology policy in Kazakhstan, showing the three main practical problems that Kazakhstan faces with the implementation of the policy in context of the “Dutch disease”.

Keywords

Innovation, Development, Policy, Regulation.

Introduction

Nowadays Kazakhstan has an emerging economy and is considered as a newly industrialised country. The economy of Kazakhstan depends on exports-exports account for 75% of GDP (World Bank, 2016). In terms of GDP growth, Kazakhstan ranks second in the former Soviet Union countries after the Russia. Kazakhstan GDP is two times larger than the GDP of four countries combined (Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan). The oil and gas sector are the main resource for the GDP structure and country suffers from the “Dutch disease” (Kutan & Wyzan, 2005; Karatayev & Clarke, 2016). Due to its high reliance on income from oil exports, the Kazakhstani economy and its competitiveness are vulnerable to changes in international commodity prices and contribution of innovation sector is neglectable. According to OECD, Kazakhstani level of innovative activity is 3.9% and this level is behind of former Soviet Union countries such as Belarus (the innovative activity was 19.6%) and Russia (9.9%) and significantly lower compare to OECD developed countries, for example, Germany (70%), Canada (65%), Belgium (60%), Ireland, Denmark, Finland (55-57%), as well as Central and Eastern European countries, where this indicator is in the range of 20-40% (OECD, 2017). There are a large number of studies demonstrating the impact and links between economic growth and innovative development (Lundvall et al., 2011; Fagerberg et al., 2012; Fagerberg, 2015). The economic success of OECD developed countries demonstrates that the innovation sectors contribute about up to 60-70% of GDP growth (OECD, 2017). The current priority for Kazakhstan is to build a knowledge-based economy and ensure the competitiveness of national economy at the global level in order to become one of the 30 most developed countries in the world by 2050. Therefore, Kazakhstan has taken many practical steps in the industrial innovation policy area to minimise impact of global oil prices fluctuations on national economy. Innovative policy is an important element of national economic development and it involves the use of certain tools, strategies and policy measures (Godin, 2009:2014). The systemic approach theory maintains that innovation happens when all of the prerequisite conditions are present (Hall & Löfgren, 2017). Government has the important role of creating and maintaining these positive conditions (Patanakul & Pinto, 2014; Gök & Edler, 2012). The role of public institutions is to minimise uncertainties in the innovation process and to encourage innovation activities (Clark, 2002; Borrás & Edquist, 2013). In terms of policy for innovation development, Kazakhstan has adopted strategies such as the Kazakhstan 2030 and the Kazakhstan 2050 strategies (Sayimova et al., 2017; Karatayev et al., 2017). Both strategies state that the country is aiming to diversify the economy, which means that in the next decades, the country’s economy will be based on innovative technologies and it will depend less on revenue from the exports of oil, gas and raw materials. At the same time, innovation and innovation policy itself is a new element in the economic development of Kazakhstan, where different institutions, public programmes and stakeholders are involved. Even though Kazakhstan has implemented a few strategies and programmes aimed at the development of science and technology, Kazakhstan faces several difficulties with establishing a comprehensive National Innovation System. Therefore, this paper aims to examine the three main practical problems that Kazakhstan faces with the implementation of the innovation policy. Previous research in Kazakhstan has examined some organisational problems associate with innovation sector from “Big Picture” (e.g., Smirnova, 2014; Aubakirova, 2015; Yessengeldin et al., 2015; Abazov & Salimov, 2016; Doskaliyeva et al., 2016). However, there is little information on financial issue, human resource potential and institutional framework. The paper applies the concept of National Innovation System Framework to examine three main practical problems for innovation sector development in the context of the “Dutch Disease”. The paper is mostly about practical aspect of innovation policy in unique case of resource-rich developing country. The analysis of the current innovation policy and regulation framework at a national level is an extremely important issue for the future successful innovation performance of Kazakhstan.

The paper is divided by four sections. The section one presents a general country introduction, introducing the drivers for innovation policy in Kazakhstan. The section two presents a discussion of the analytical framework for innovation policy in Kazakhstan, the National Innovation System Framework. The section three provides background information on the innovation policy in Kazakhstan, including strategic documents and state programmes on innovation policies. It contains a review of the aims and objectives of the state programmes and its current implementation. The section fourth examines the problematic aspects of current innovation policy in Kazakhstan. The final section provides conclusion and some recommendations for overcoming these problems.

Methodology

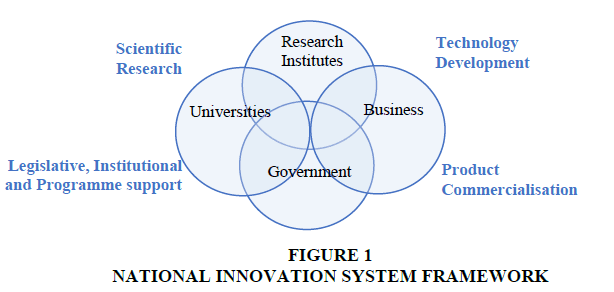

The concept of National Innovation System Framework is the process of integrating different objectives and actors (government, research organisations, universities, companies) that are interacted and linked with each other in the creation of scientific knowledge, innovations and technologies (Godin, 2009). Lundvall (1992) defined the National Innovation System Framework as being “Constituted by elements and relationships which interact in the production, diffusion and use of new, and economically useful, knowledge’’. This approach suggests that innovation is systemic work, where public research institutions, universities, financial organisations, policy-making organisations, training institutions, technological support institutions, industry and others interact together (Adams et al., 2006; Bassett?Jones, 2005). The performance of this system depends on the actors and their links with each other. Based on this idea, national governments around the world try to strengthen university-industry linkages. Currently, the National Innovation System Framework covers all the main components of the innovation process, including organisational, social, political and economic factors. This concept is widely used by researchers and decision makers at multi-levels for analysis the national innovation policies (Godin, 2009). The methodology for this paper has thus been conducted with the adoption of the concept of National Innovation System Framework in case of Kazakhstan. In addition to the National Innovation System Framework, the review of literature has been conducted with the help of extensive secondary information, obtained from various sources including national programmes, strategic documents and recent legislative base: Law “On commercialization of the outcomes of scientific and technical activities”, Law “On protection of intellectual property rights”, Law “On commercial code of the Republic of Kazakhstan”, Law “On Science” and Law “On government support for industrial and innovation activities”.

Policy Framework for Development of Innovation Sector To improve its industrial and innovation policy, Kazakhstan has established a number of institutions to support innovation including R&D, universities, consulting, business and governmental bodies (Figure 1). The roles of other previous organisations were reformed to incorporate the implementation of the new priority areas of research and innovation activities (Bhuiyan, 2010). The national innovation policy is determined and implemented by governmental organisations, which consist of 15 ministries headed by the Prime Minister. In accordance with the adopted laws and state programmes on industry and innovation development, three ministerial organisations (the Ministry of Education and Science, the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade, and the Ministry of Industry and of New Technologies of Kazakhstan) are responsible for planning, organising, coordinating and monitoring industry and innovation activities (Karatayev et al., 2016). The main strategic body is the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Education and Science, established in 2006. The Committee coordinates and implements policy in the field of R&D and scientific activities in the country. It also monitors the implementation of scientific and technical programmes and projects. This Committee brings together representatives from national research agencies, national universities and research institutions to make high-level decisions and to support government activities in the areas of R&D and innovation policy. The Committee has advisory responsibilities that include providing proposals and recommendations on priority areas for research. The Committee make decisions on grants and targeted financing programmes from the public budget and providing proper legislative environment for innovation development. According to OECD (2017), Kazakhstan has significant R&D potential for innovation development. For example, research institutes in such field as physics, mathematics, chemistry, earth science, are characterized by high publication activity and high citation level. However, one of the main problems of science in Kazakhstan is the incompleteness of research and its separation from production and commercialisation. Most research organisations in Kazakhstan do not incorporate the necessary engineering infrastructures (engineering and technological services, start up production), designed to deal with implementation of scientific ideas, innovations and technologies. To provide linkages of R&D, universities and business, the government created National Science and Technology Holding “Samgau” with responsibilities of marketing research and service provision, financial and legal analysis of research projects, assistance in attracting financial resources from business. Priority areas identified by the National Science and Technology Holding are telecommunication and information technology, nanotechnology, biotechnology, renewable energy technology, mining and metallurgical sector. Regarding legislative and programme support, official documents on the innovation policy at different levels have been introduced and adopted and they have been functioning to promote the innovation policy in the country in order to achieve the sustainable development of the economy (Table 1). These documents can be grouped according to their official level and set priorities. In 1997, the government introduced a long-term strategy called “Kazakhstan 2030”. This strategy seems to be a roadmap for institutional, social and economic reforms. In the first version, the strategy covered long-term priorities related to sustainable economic development and growth, while issues related to innovations were ignored. In 2015, Kazakhstan developed a new long-term development strategy “Kazakhstan 2050”. This strategy includes many elements relating to various aspects of innovation. For example, the strategy approved the development and establishment of two innovation clusters: Nazarbayev University in Astana and the park of innovative technologies “Alatau” in Almaty. One of the priority projects for the implementation of the strategy “Kazakhstan 2050” has been an increase in financial funding for R&D to 3% of GDP per year by 2020. In 2015, the public financial allocation for R&D was less than 0.3% of GDP. This figure is lower than the average in OECD countries, which was 2.8% of GDP in 2015 (OECD statistics, 2017). The first specific document designed for developing innovation in the country was the Strategy of industrial and innovative development of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2003-2015. This document was an umbrella document and it provided the general background for the development of the following innovation programmes as it was designed in line with the national development strategy “Kazakhstan 2030”. The strategy described the challenges and threats that Kazakhstan has faced in the area of innovation development; it defined the goals and priorities with regard to this issue, and indicated the tools for conducting the strategy. The expectation of this programme was that it would change the economic structure and industrial production and stimulate innovation capacity (Aubakirova, 2015). In particular, it was expected that Kazakhstan would achieve the following outcomes: an increase in the share of innovative production in the national economy to 20-30%; an increase in the Kazakhstani innovation production in the world markets of high-tech goods and services to 1-3%; an increase in the share of exports of high-tech products; an increase in the contribution of innovative products and services to GDP; a threefold increase in R&D expenditure. The amount of financial resources allocated to the realisation of the Strategy was 147,903.08 Kazakh Tenge. Over the period of the implementation of the Strategy 2003-2015, a system of institutions for industrial innovation was created, and various laws and sub-programmes were adopted. Between 2007 and 2012, because of the implementation of the Strategy 2003-2015, the level of innovative activity grew by 2.6%, and the volume of innovative products increased by 240% (National Statistics Agency, 2015). However, in 2014, the Strategy for 2003-2015 was cancelled because national government proposed new strategies for the development of innovation. In 2005, the national government developed and adopted the State Programme on Formation and Development of National Innovation System of Kazakhstan for 2005-2015. The programme set six objectives within four stages of implementation: research capacity development, building and developing an innovative entrepreneurship environment; the formation and development of a multifaceted innovation infrastructure; the formation and development of a financial infrastructure along with venture findings; the provision of effective interaction between the elements of the National Innovation System; and developing legal acts to support innovation. Five sectors of the State Programme on the Formation and Development of the National Innovation System were set as a priority. These sectors included energy efficiency through new technologies; growth of non-resource sectors; machinery manufacturing, which plays a central part in innovation development; the agricultural sector; small and medium business development; labour productivity, which increases the social development of Kazakhstani society. The cost of the programme for the period 2005-2015 was 139,795.13 million Kazakh Tenge. 60,419.83 million Kazakh Tenge was allocated from local and foreign investments while the remainder was allocated from the republican and local budget. In 2010, the State Programme on Accelerated Industrial and Innovation Development for 2010-2014 was adopted. The developers and authors of this programme were two ministries-the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade, and the Ministry of Industry and of New Technologies of the Republic of Kazakhstan. The difference in this programme was its objective. Compared to the State Programme on Innovation Development and Technological Modernisation for 2010-2014, the State Programme on Accelerated Industrial and Innovation Development for 2010-2014 focused on the implementation of major investment projects in export-oriented sectors of the economy. The programme provided a list of specific investment projects in different regions of Kazakhstan. Over the years of implementing the programmes, Kazakhstan managed to achieve some positive outcomes. As stated in the final report on the implementation of the Strategy 2010-2014, at least the process of economic diversification has been launched. The share of innovative enterprises in the structure of the economy grew from 3.2% in 2008 to 8.1% in 2014 and the volume of innovative products increased by 420% (National Statistics Agency, 2016). However, this number is significantly low compared to the international average in developed and OECD countries. The average share of innovative active enterprises in OECD countries is about 47% (OECD Statistics, 2017). The State Programme on Industrial and Innovation Development for 2015-2019 is an extension of the previous Programme for 2010-2014 and incentive diversification and an increase in competitiveness for the secondary sector (manufacturing sector) are at the centre of this programme. The programme was formed in accordance with the principles and objectives of Kazakhstan's entry into the top 30 most developed countries. The concept has focused on key reforms, providing rule of law, proper professional and institutional service, and attraction of investments, industrialisation, and transparency. This State Programme on Industrial and Innovation Development is to be a main long-term programme with the intention of transforming the economy from resource based to innovation based (Yessengeldin et al., 2015). The Programme 2015-19 focuses on a cluster approach to developing innovation. Clusters in particular are seen as drivers of innovation by creating innovative milieus and supporting “Knowledge Regions” (Audretsch & Feldman, 1996). The cluster approach is seen in this Programme as a mechanism for attracting investors (Aubakirova, 2015). The Programme objectives consider the impact of government policy on the business climate. The intention of using a cluster approach is to design the Programme so that it responds to the business climate (Doskaliyeva et al., 2016). The first measures to support industrial and innovation development are demonstrated in the Law “On Science”. These laws facilitate three ways of industrial and innovation development: basic, grant and result-oriented financial support. The bodies responsible for setting the scientific and technical direction of the policy are first the Ministry of Education and Science, which directs industrial and innovation development through educational institutions; and second, the Ministry of Industrial Development, which supervises the industrial aspect of the policy. These responsibilities are defined within this law. The creation and maintenance of a favourable environment for industrial and innovation development is regulated by the Law “On government support for industrial and innovation activities”. This law defines the regulations on the development of priority sectors in industrial and innovation development and the development of high-technology products, along with the implementation of innovations. The role and the status of the participants of industrial and innovation development are regulated with the articles of the Law “On commercialization of the outcomes of scientific and technical activities”. The ownership of intellectual property is clearly defined within this law. It says that the results of research financed by the government budget belong to organisations. Authors are given compensation for their research outcomes. The rights and support of industrial and innovation activities of enterprises are protected by the Law “On commercial code of the Republic of Kazakhstan”. The objective of this law is to consider the activities of enterprises and other participants in industrial and innovation development, in order to increase the incentives to develop special economic zones, which are priorities in the economy, and to create an industrial and innovation system. Also, Kazakhstan adopted the Law “Protection of Intellectual Property Rights”. Problems with the Implementation of the Innovation Policy Despite the solid programme framework for innovation and R&D, its practical implementation remains weak (Smirnova, 2014). The significant problem associated with innovation development in Kazakhstan is human resource potential for R&D sectors. According to national statistics, approximately 23000 people were involved in R&D sector in 2016 in Kazakhstan (KAS, 2014). This number decrease over the last two decades by 37% and the current number is significantly lower compare to OECD developed countries (Karatayev et al., 2016). According to OECD statistics, Kazakhstan is behind of many of the leading countries of the world. For example, in countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium, whose population is comparable to Kazakhstan (17 and 11 million people respectively), the number of researchers is 3-4 times higher than in Kazakhstan (79971 and 59307 respectively). Furthermore, Kazakhstan faces the aging problem of its human resource potential. The share of researchers of preretirement and retirement age over 55 years accounted for almost 43.5% of the whole human resources contingent in R&D sector. But in general, there is a tendency to a slight decrease in this age group. Qualification background of researchers in Kazakhstan is the most represented by candidates of science (4726 people) and doctors of science (1828 people), among them, there are 1906 candidates and 1302 doctors of science over the age of 55. Apart from that, the human resource potential is unevenly distributed among the country. The largest city of Almaty remains the main scientific center of Kazakhstan. The number of R&D workers in Almaty in 2016 was about 9500 people. This number is more than 40% of all human potential in R&D sector in Kazakhstan. Astana was the next city in number of scientific workers in the region of Kazakhstan, the share of research R&D workers was about 13% of total. Then the East Kazakhstan region accounts for 9.6%, Karaganda region 6.3%, South Kazakhstan region 4.7% and Almaty region 4.3% (KAS, 2016). Regarding international R&D specialist working in Kazakhstan, at the end of 2016, only 270 international scholars worked in Kazakhstan’s R&D sector, including 240 people from Former Soviet Union (FSU) countries and 37 from non-FSU countries. Another main problem area is insufficient funding of R&D sector from both public and private institutions. According to the National Statistics Committee of the Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 383 organizations were involved in research and development in 2017 in Kazakhstan (KAS, 2018). Only 35% of the total number of R&D organizations was belonged to national program of financial support for R&D sector. In 2015, Kazakhstan spent 0.14% of its GDP for R&D sector. In comparison, this number was 0.29 in 2008, the period of high oil prices. The largest share of R&D expenditures was focused on engineering and manufacturing; 45% of the total expenditures in the country. In addition to this field of science, in 2016 the share of social sciences increased by 0.4%, but in the total volume of expenses this area of science was only 1.6%. The largest share in the cost structure (67%) belonged to wage fund. The main source of salary payments to all categories of workers is the wage fund, the funds of which are formed at the expense of the R&D project cost. Over the last five years, it was observed a decline in salaries for R&D workers in general, as well as in the public sector and in the higher education sector due to recent oil price reduction (KAS, 2018). The decline in public spending forced R&D organizations in Kazakhstan to look for other sources of funds for research from private business sector. However, private sector has not significant interest to invest in local R&D sector due to disbelief in efficiency and productivity of national R&D system. As result, the current contribution of private sector to national R&D system is less than 0.02% of GDP. According to the OECD statistics, the share of R&D expenditure of private sectors in OECD countries is approximately 30% to total national expenditure of GDP. Another challenge includes a weak legislative base. For example, an important element of the innovation policy is the infrastructure, including business centres, innovation parks and technoparks (Saiymova et al., 2014). Currently, national legislation does not contain clear criteria for determining the status, financing and granting benefits to innovation parks and techno-parks in Kazakhstan (Abazov & Salimov, 2016). There is also a lack of clear mechanisms regarding the protection of intellectual property. According to the International Property Right Index, Kazakhstan is at the bottom of the list of 130 countries (Property Rights Alliance, 2015). The worse components of the Kazakhstani innovation performance are: the legal and political environment, the protection of the rights to physical and intellectual property and the efficiency of the existing legislative base. The first three places in the ranking belong to Finland, New Zealand and Sweden. The ten countries where owners can feel most secure include Norway, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Singapore, Canada and Denmark. Kazakhstan was in the group of countries with a total index of 4.5 points, placing it in a group with countries such as Nepal, Senegal, Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan. The report also stated that Kazakhstan should improve its legislative base in specific areas including the right to receive state support; the right of independent and free choice of the direction and types of innovation activity; the right to form internal funds to support innovation; the right to access scientific and technical information; and the right to invite on a contract basis co-executors required for the implementation of innovative activities. Furthermore, the legislative base should provide a framework for attracting investment and allocation incentives for the development of business incubators, techno-parks, and R&D and innovation parks. In particular, the legislative base should provide a framework regarding rental rates, a system of fixed-term contracts with small and medium-sized enterprises, technoparks in industrial enterprises, innovative industrial complexes and technology clusters out of the university environment (Abazov & Salimov, 2016). Kazakhstan sets ambitious, but achievable, goals for long-term development, which consist of providing a high level of socio-economic and industrial innovative development. The possible way to achieve these goals is to help the economy to transform from oil base to an innovation-oriented model of development. However, the problems described above hinder the development of Kazakhstan's National Innovation System; their complexity and scale indicate that a rapid leap to an innovation-based economy is impossible. One of the main problems facing the innovation system of Kazakhstan is human resource potential for R&D. Kazakhstan has a national educational program “Bolashak”. The program provides an opportunity to get an international education at undergraduate and postgraduate levels in the best universities of the world. It is recommended to increase the number of scholarships for PhD programmes, as well as to create a post-doctoral and research placement programmes. Furthermore, the government remains the main source of funding in R&D sector in Kazakhstan, while dependence of R&D sector on this source is very high. The private sector in Kazakhstan is not interested to order research projects from Kazakhstani scientists and engineers. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new approaches to the funding schemes for R&D. Based on best practice of developed countries, it might be better to categorise scientific organizations according to their scientific potential (human resource potential, the effectiveness of research projects and its outputs, the availability of its own laboratories, etc.). For example, the first two categories should include scientific organizations that have established “Scientific Schools” and traditional international relations that are well-known to the world community of scholars. The third category it is advisable to include scientific organizations and departments of higher education institutions that begin their activities. The amount of R&D funding for the first two categories of scientific organizations should be at least 80% of the total national funding. Finally, a weak legislative base should be revised and strengthened. Currently, national legislation does not contain clear criteria for determining the status, financing and granting of benefits to innovation parks and techno-parks. There is also a lack of clear mechanisms regarding the real practices of innovation projects, including the right to receive state support; the right of independent and free choice of the direction and types of innovation activity; the right to form internal funds to support innovation; the right to access scientific and technical information; and the right to invite on a contract basis co-executors required for the implementation of innovative activities.

Table 1

Legislative, Institutional And Programme Support

2002

Strategy of industrial and innovative development of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2003-2015.

2005

State Programme on Development of National Innovation System of Kazakhstan for 2005-2015.

2007

Committee of Science of the Ministry of Education and Science established.

2006

Ministry of Industry and of New Technologies established.

2007

National Science and Technology Holding “Samgau” established.

2009

State Programme on Accelerated Industrial and Innovation Development for 2010-2014.

2011

Law “On Science”.

2012

Law “On government support for industrial and innovation activities”.

2013

National concept on innovation development until 2020

2014

State Programme on Industrial and Innovation Development for 2015-2019.

2015

Law “On commercialization of the outcomes of scientific and technical activities”.

2015

Law “On protection of intellectual property rights”.

2016

Law “On commercial code of the Republic of Kazakhstan”.

Conclusion

References