Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 5

The Link between Parental Socioeconomic Status (SES) and Childrens Future Employment Prospects: A Conceptual Framework

Mussie Tessema, Winona State University

Parag Dhumal, University of Wisconsin-Parkside

Michele Gee, University of Wisconsin-Parkside

Samuel Tsegai, Winona State University

Citation Information: Tessema, M., Dhumal, P., Gee, M., & Tsegai, S. (2022). The link between parental socioeconomic status (SES) and children’s future employment prospects: A conceptual framework. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 21(5), 1-16.

Abstract

The link between parental socioeconomic status (SES) and school-age children’s educational success has been well documented. This study, however, explains the link between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects in greater detail. It reviews the extant literature and develops a conceptual framework. As children’s future employment prospects represent a multi-faceted and complicated issue, parental SES outcome (education) can be used as a mediating factor between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects. This study argues that the variations in children’s educational success can constrain or enable children’s future employment prospects. The current study underscores that parental SES appears to influence children’s educational success, which subsequently impacts their future employment prospects. The implications of the study and directions for future research are discussed.

Keywords

Socioeconomic Status, Education, Children, Students, Academic Achievement, Employment.

Introduction

Employment is an important aspect of human life. The scriptures tell us that if a man will not work, he shall not eat. People spend a significant amount of their time at the workplace. They often work for an employer, as an independent contractor, or are self-employed; and the type of work they do has a profound impact on their life, and specifically influences their earnings (Gowan, 2022; Phillips, 2022), health (Carneiro & Heckman, 2003; Cunha & Heckman, 2009; Neppl et al., 2016), and happiness/satisfaction (Lussier & Hendon, 2017). The type of work they do is often influenced by their type and level of education. A good education undoubtedly has the power to change the quality of one’s life (Carnevale et al., 2013; Marks, 2006). In the 21st century, education has become a weapon to enhance people’s lives by improving people’s knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs), which in turn affects their chances of employment. Walker (2006) noted that education is not only a capability by itself but also an enabling factor for people to achieve their objectives.

Previous studies indicated that children’s educational success is impacted by myriads of factors, one of which is parental SES (Chen et al., 2018; Jæger, 2012; Li et al., 2020; Lyu et al., 2019; Smits & Ho?gör, 2006; Zhang & Xie, 2016). A very large body of literature has long documented the influence of parental SES on children’s educational success, which subsequently impacts their future employment prospects. Many studies have also indicated that parental SES explains most of the variance in children’s educational success (Berkowitz et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2018; Lawson & Farah, 2017).

Research has shown that individuals’ employment can be impacted by several factors, such as educational credentials (Harvey, 2000), networking (Davis et al., 2020; Phillips, 2022), quality of school (Merritt, 2016; Morgeson & Nahrgang, 2008), grade point average (GPA) at college (Knouse et al., 1999; Lyons & Bandura, 2017), a field of study or discipline (Beffy et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2015), unemployment rates (Roth & Bobko, 2000); communication, interpersonal, analytical, critical, computer, and technical skills (Gowan, 2022; Lussier & Hendon, 2017), labor market – specifically supply and demand of labor (Carnevale et al., 2013; Garrett, 2020), work experience (Gowan, 2022; McMurray et al., 2016), and cultural-fit (Rivera, 2015; Smith, 2017). Many of these factors are related to an individual’s educational success, and thus, to have better employment opportunities the 21st century workplace requires individuals to have a good education. Accordingly, this study contends that education is the most important factor as it provides people a competitive advantage while looking for work. Getting a good education plays a vital role in helping people acquire the KSAs they require, which then enhances their employment prospects. People have better job prospects when they have higher levels of education (Carnevale et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2015; Lyu et al., 2019). Without educational success, an individual could be at an extreme disadvantage. Thus, having a good education has evolved from something nice to have, to something one must-have.

Although many studies have been conducted on the link between parental SES and children’s educational success, there is a paucity of studies on the link between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects. Although some studies have highlighted the link between SES and employment (Lyu et al., 2019; Morsy & Rothstein, 2015; Sastry & Pebley, 2010), there is little research that highlights the link between parental SES and children’s future employment. This study, therefore, addresses this gap by developing a conceptual framework to explain the link between parental SES and children’s educational success and future employment prospects. It tries to answer the following research questions: (1) what factors affect children’s educational success? (2) How does parental SES affect children’s educational success? (3) What factors affect children’s future employment prospects? (4) How does parental SES affect children’s future employment prospects? (5) To what extent does parental SES affect children’s future employment prospects? And (6) what are the implications of this study’s findings?

Literature Review

The link between parental SES and children’s educational success has been well documented. This study explains the link between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects. Education is a major economic and social determinant of almost all aspects of life (Walker, 2006) and is considered key to achieving economic success and social mobility (Becker, 1992; Brecko, 2004). Parental SES is among several factors that influence children’s educational success.

Parental SES refers to the general economic and social position of parents in relation to others (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). It is measured by the social and economic status of family members (Chen et al., 2018) and is more commonly used to show economic differences in society as a whole, (Aikens & Barbarin, 2008; Gardner-Neblett & Iruka, 2015). It is a widely studied construct in the social sciences (Morsy & Rothstein, 2015). SES is typically broken into three levels (high, middle, and low) to describe the three places a family or an individual may occupy (Aikens & Barbarin, 2008; Morgeson & Nahrgang, 2018). Previous studies have utilized different elements of parental SES; for example, income, occupation, accommodation, and living region (Warner et al., 1949); education level and occupation (Hollingshead & Redlich, 1958); income, education level, and occupation; education, occupational status, and income (Jiang et al., 2018); and education, occupational status, income, and household size (Choi et al., 2020). In this study, parental SES includes education, occupation, household size, and income. Parental education refers to the parent’s education level and is measured using educational credentials such as presecondary school (elementary, middle, and secondary) and post-secondary school (associate, undergraduate, and graduate degrees) (Chen et al., 2018; Vellymalay, 2012). Parental income refers to parents’ salaries, wages, and any flow of earnings received such as income in the form of dividends, trusts royalties, interests, pensions, and other families, governmental, or public financial assistance (Benson & Borman, 2010; Zhan, 2006). Parental occupation refers to the type and level of parents’ occupation (Shah & Anwar, 2014) and can be measured based on the level of skills involved (from skilled to unskilled or professional to manual labor) (Vellymalay, 2012). Household size refers to the size or number of children born to a parent (Dang & Rogers, 2016).

For instance, Americans can be grouped into the upper, middle, and lower classes (Kochhar, 2018). While high SES parents may refer to high-income earners, who are likely to be highly educated and have high-status occupations and powerful social networks, low SES parents may refer to low-income earners, who are more likely to have low levels of education, low-status occupations, and weak social networks, and may be employed in hard labor. Thus, parental SES affects the quality and quantity of resources that parents mobilize for their children’s educational activities.

While educational success may refer to the extent to which an individual completes pre and/or post-secondary education, children’s future employment prospects may refer to the extent to which children will be able to gain employment and be successful in their occupations of choice. The completion of educational benchmarks such as secondary school diplomas and bachelor’s degrees may represent educational success (Chen et al., 2018; Milne & Plourde, 2006). This study assumes that as educational success rises, the employment prospects increase, and vice versa.

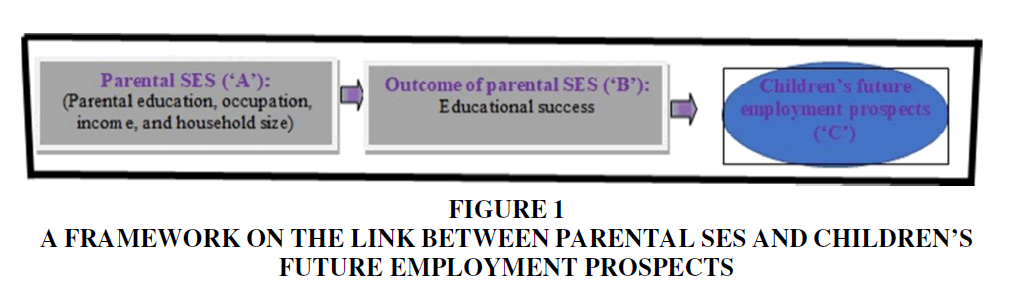

Considering the objectives of the current study and the relevant literature, we developed a conceptual framework (Figure 1) to explain the link between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects.

The conceptual framework is based on the following assumptions:

1. Children’s future employment prospects (C) are impacted by several factors. Educational success (B) is one of them and is impacted by myriads of factors, including parental SES (A).

2. Although many factors that influence parental SES, the following four are most important: parental education, occupation, income, and household size.

3. If a child’s parents have high SES, he is more likely to enjoy higher educational success.

4. Parental SES influences children’s educational success, which influences their future employment.

The Link between Parental SES and Children’s Educational Success

What factors affect children’s educational success?

This study argues that there are many factors (e.g., parental SES, qualification of teachers; parental involvement, geographic location of schools, intrinsic motivation to learn, and self-control) that affect children’s educational success. However, parental SES is one of the main factors that impact children’s educational success. The four components of parental SES are discussed below.

Parental education level and children’s educational success

Parental education level is a major factor that influences children’s educational success (e.g., Chen et al., 2018; Eccles, 2005; Jæger, 2012; Jiang et al., 2018; Marks, 2006; Teachman & Paasch, 1998; Wiederkehr et al., 2015). This study argues that children of educated parents have an advantage over those of uneducated ones, as educated parents have knowledge and experience of supporting their children’s education and tend to set high expectations and aspirations for them.

Parental occupation and children’s educational success

Parental occupation impacts children’s educational success (Li et al., 2020; Shah & Anwar, 2014; Vellymalay, 2012). This study argues that children of parents in white-collar positions (e.g., managerial, professional, and technical) have an advantage over children of parents in blue-collar positions (e.g., agriculture, manufacturing, construction, or mining) for they can access greater resources to support their education.

Parental income and children’s educational success

Parental income shapes children’s educational success (e.g., Chen et al., 2018; Dang & Rogers, 2016; Karagiannaki, 2017; Perrons & Plomien, 2010; Wang et al., 2014; Zhan, 2006). These studies showed that parental income has a profound effect on children’s educational success. The current study argues that children of parents with adequate income have an advantage over children of parents without adequate income as they can access greater resources (financial, social, and cultural capital), which in turn positively influences their education.

The size of the household and children’s educational success

The size of the household influences children’s educational success (Choi et al., 2020; Dang & Rogers, 2016; Karagiannaki, 2017; Li et al., 2020). This study argues that children from small households have an advantage over those from large households as they receive more resources (financial, energy, and attention) per child, which in turn positively influences their education (Karagiannaki, 2017; Li et al., 2020).

How does parental SES affect children’s educational success?

Parental SES impacts children’s academic success in many ways. The extent of the parents’ SES can determine the number of resources they can invest in their children’s education (Becker, 1992; Lyu et al., 2019; Morsy & Rothstein, 2015; Sastry & Pebley, 2010). The resources invested in children’s education have a profound effect on their educational success. This study contends that parental SES is the most important factor in children’s educational success. Five theories can help explain the link between parental SES and children’s educational success. These theories are as follows:

The Family Investment Theory

It assumes that the parents’ investment of resources (e.g., financial, human, and social capital) can promote the development of their children. It focuses on the role of parental economic resources and investment in children’s education. The parents’ investment of resources in their children’s education can explain the link between their SES and the children’s educational success (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Francesconi & Heckman, 2016; Kalil & Deleire, 2004). Parents with a higher SES are able and willing to invest more resources in their children’s education, which in turn impacts their children’s education success. As parents believe that the benefit of their children’s educational investments exceeds their cost, those who have enough resources are willing to make educational investments. The cost-benefit analysis of educational investment encourages parents to mobilize resources for their children’s educational, which, in turn, impacts their educational success (Francesconi & Heckman, 2016; Conger & Donnellan, 2007). The difference in children’s educational success is mainly because of the difference in parental educational investment (Becker, 1964; Vasilyev et al., 2018). Owing to the limitation of parental resources, parents with low SES are often unable to adequately invest in their children’s education.

The Social Capital Theory

The social capital theory assumes that parental social capital (i.e., parents’ social position in one’s society) impacts children’s learning behaviors and educational success (Jæger, 2012; Zhang & Xie, 2016). It argues that parental social relationships can lead to the development and accumulation of human capital and focuses on the role of parents’ educational level and participation in children’s educational activities, thus arguing that parental SES influences children’s educational success (Coleman, 1988; Powell & Parcel, 1999). Social capital refers to the possession of social contacts that can open doors and is a critical source of power and influence that supports individuals to get by and get ahead (Coleman, 1988; Powell & Parcel, 1999). The social capital theory further assumes that parents with higher SES usually partake in their children’s learning activities such as by checking homework, communicating with teachers, participating in school activities, managing the children’s school absence, and other risky behaviors, all which impact children’s educational performance (Coleman, 1988; Jiang et al., 2018). Previous, research has also shown that parental social capital enhances children’s educational success (Pong et al., 2010; Powell & Parcel, 1999).

The Cultural Capital Theory

The cultural capital theory assumes that parental cultural capital (e.g., the accumulated cultural knowledge that grants social status and power) affects children’s educational aspirations and success (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990). Cultural capital refers to the knowledge and skills that individuals can draw on to give them an advantage in social life (Stevenson & Stigler, 1992). Having knowledge, skills, norms, and values can help one get ahead in life in general, and in education in particular. The cultural capital theory also assumes that parental cultural capital can put their children in a better social position (Coleman, 1988; Sullivan, 2002). Children from high SES backgrounds tend to have more cultural capital than those from low SES backgrounds, and this gives them an unfair advantage (Sastry & Pebley, 2010; Reardon, 2011). Compared to parents with inadequate cultural capital, parents with rich cultural capital make efforts to cultivate the educational aspirations and interests of their children (De Graaf et al., 2000; Liu & Xie, 2016; Sastry & Pebley, 2010; Teachman & Paasch, 1998), tend to be aware of the rules at school (Sullivan, 2002), and help their children with school work (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990; Liu & Xie, 2016).

The Resource Dilution Theory

The resource dilution theory assumes that children with many siblings receive less support from their parents than those with small families (Karagiannaki, 2017; Zhan, 2006). Parents have finite resources (e.g., limited time, money, and patience) to allocate to their children’s education. Its assumption is on the lines of the classic view of the quality-quantity trade-off in family economics (Becker & Tomes, 1976). Parents with fewer children can invest more resources per child, which, in turn, can impact their children’s educational success. When the size of the household is small, children tend to receive more parental attention in educational activities. Conversely, when the size of the household is large, children tend to receive lesser parental attention in educational activities, and this influences their educational performance adversely. Research has shown that children from small households received more parental attention in educational activities than those from large households (e.g., Choi et al., 2020; Dang & Rogers, 2016; Karagiannaki, 2017).

The Social Causation Theory

The social causation theory assumes that experiencing economic hardship increases the risk of subsequent issues that threaten individual lives and cause parents to fall into the lower SES band (Hoffmann et al., 2018). It argues that parents’ SES influences their emotional relationship and parenting behaviors, which, in turn, influence their children’s educational success (Conger & Conger, 2002; Hoffmann et al., 2018; Neppl et al., 2016). Social causality refers to a social process that generates a change in some dependent variable. When parents have economic hardships, unconducive working conditions, stressful work environments, marital conflicts, or mental illnesses, they are more likely to feel tired, depressed, pessimistic, and hopeless. Consequently, they are more likely to give less value and importance to their children’s education and to offer lower levels of academic support to their children, which will negatively influence their children’s educational success (Chen et al., 2018; Francesconi & Heckman, 2016). Such a situation can create more threats to their children’s social identity. (There is a hidden statement in here)

Empirical research has supported the abovementioned theories explaining the link between parental SES and children’s educational success. For instance, the parental SES influences the extent to which parents are able (have the required resources) and willing (have the willingness) to:

- Shape their children’s skills, views, and behaviors toward school (Magnuson, 2007; Vasilyev et al., 2018),

- Provide conducive and stimulating home learning environments (Wang et al., 2014; Zhan, 2006),

- Enroll their children in high-quality schools (Chen et al., 2018; Lyu et al., 2019),

- Let their children participate in extracurricular activities that influence academic performance (Abruzzo et al., 2016; Yeung, 2015),

- Prioritize and value the importance of children’s education (Dang & Rogers, 2016; Neppl et al., 2016),

- Closely monitor their children’s school activities (Li & Qui, 2018; Teachman & Paasch, 1998),

- Serve as role models and mold their children appropriately right from an early age onward (Jæger, 2012; Wiederkehr et al., 2015),

- Provide more learning opportunities and resources such as high-quality private tutoring (Neppl et al., 2016; Zhang & Xie, 2016), get involved in their children's schooling.

- Send their children to schools with good facilities and qualified teachers (Cunha & Heckman, 2009; Perrons & Plomien, 2010),

- Have more positive psychological outcomes like optimism, self-esteem, and perceived control (Liu & Xie, 2015; Mahoney et al., 2005),

- Engage in parenting practices that are conducive to children’s educational success (Lareau, 2011; Vellymalay, 2012), and spend time and energy that will be directed toward supporting their children’s education (Berkowitz et al., 2017; Kraus & Keltner, 2009).

The Link between Parental SES and Employment

What factors affect children’s future employment prospects?

Several factors impact an individual’s employability. Some of the important ones are educational credentials (Harvey, 2000), quality of school (Merritt, 2016; Morgeson & Nahrgang, 2008), GPA (Knouse et al., 1999; Lyons & Bandura, 2017), a field of study or study discipline (Beffy et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2015), work experience (Gowan, 2022; McMurray et a1., 2016), networking (Davis et al., 2020; Phillips, 2022), cultural-fit (Rivera, 2015; Smith, 2017), communication, interpersonal, analytical, critical, computer, and technical skills (Gowan, 2022; Lussier & Hendon, 2017), extracurricular activities (Abruzzo et al., 2016; Li & Qui, 2018), the labor market (Carnevale et al., 2013; Garrett, 2020), and unemployment rate (Roth & Bobko, 2000). This study argues that during the hiring process, employers offer due attention to the above factors, of which many are related to the job applicants’ educational success. Many of the abovementioned factors are also impacted by parental SES.

How does parental SES impact children’s future employment prospects?

This study argues that parental SES impacts children’s future employment through the parental SES outcome (education), which serves as a mediating factor between parental SES and future employment prospects.

The most popular theory that explains the link between education and employment is the human capital theory, which has had a profound impact on a range of disciplines from economics to education and sociology (Tan, 2014). The human capital theory assumes that formal education is necessary to improve the productive capacity of a population (Almendarez, 2011). It posits that education is a vital human capital investment (Schultz, 1961; Becker, 1964) that yields return in due course to educated individuals in terms of employment opportunities and earnings. It assumes that an educated population is productive and emphasizes how education improves the productivity and efficiency of individuals by improving the level of KSAs. It has been widely accepted as a basis for why people seek education. As an investment in human capital (Becker, 1964), education enables individuals to participate in the productive sector and opens doors to more job opportunities. It argues that investing in education has a payoff in terms of employment opportunities and higher earnings.

The following empirical studies also support the notion of the human capital theory, which explains the link between education and people’s employment. For example, education in general and post-secondary education in particular impact people’s employment prospects by improving the KSAs necessary for success in a specific area (Phillips, 2020), improving self-confidence and self-discipline (Eccles, 2005; McMahon, 2009), enhancing communication, interpersonal, analytical, critical, technical, and computer skills (Gowan, 2022; Lussier & Hendon, 2017), helping students become more creative and develop new ideas (Kraus & Keltner, 2009; Marginson, 2019), promoting entrepreneurial spirit (Harvey, 2000; McMahon, 2009), providing a sense of empowerment (McMahon, 2009; Walker, 2006), refining the thinking process and changing the perspective on the outside world (Lussier & Hendon, 2017; Phillips, 2022), helping narrow down the interest range and refining skillsets (Eccles, 2005; Psacharopoulos, 2006), improving critical thinking and problem-solving skills, time management, team work, and perseverance (Li & Qui, 2018; Marginson, 2019), increasing cultural awareness and worldliness (McMahon, 2009; Smith, 2017), polishing the mind, reinforcing thoughts, and strengthening character, and behaviors toward others (Harvey, 2000; Walker, 2006). These findings suggest that education can help individuals gain hard and soft skills that are essential for the 21st century workplace.

Education plays a major role in career and personal growth. The more education we get, the more employment opportunities we have. Besides, the KSAs that individuals acquire through education can also be used for the betterment of society, country, and the world at large.

To what extent does parental SES impact children’s future employment prospects?

The extant literature shows that parental SES influences employment prospects. Although research has shown that parental SES impacts children’s future employment opportunities (e.g., Carnevale et al., 2012; Rivera, 2015; Smith, 2017), it has not indicated the extent of such impact. This study emphasizes that although parental SES impacts employment prospects, it is not easy to accurately know the net effect of parental SES on children’s future employment prospects, mainly because of intervening variables. Unless very careful controls are used to take account of all factors that may affect children’s future employment prospects, the results may overstate or understate the influence of parental SES on children’s future employment prospects. Children’s future employment prospects are, therefore, not the direct result of any one factor such as parental SES. Rather, parental SES is one critical element among a diverse set of influences that determine children’s future employment prospects. This study acknowledges these methodological challenges and aims at examining how they can be addressed. It contends that, although our knowledge of the net impact of parental SES on children’s future employment prospects is still incomplete, there is no shortage of assumptions around the link between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects. Despite the absence of unambiguous proof of the net impact of parental SES on children’s future employment prospects, research has provided evidence of the nexus.

This study further argues that if we are to speak with any certainty on the extent to which parental SES impacts children’s employment prospects, we must first isolate the effect of parental SES on children’s employment prospects by controlling the rest of the factors that affect children’s employment prospects. Thus, this study argues that we need to have a theory to define the extent to which the variances matter, and how much of the variance can be explained by parental SES.

Discussion

This study emphasizes that employment is a vital aspect of life. If we are to compete and win in a tough labor market, we must have a competitive advantage, and one way of making ourselves more competitive is through education. This study argues that many factors that impact children’s educational success, and parental SES is one of them because it influences the quantity and quality of resources parents that invest in their children’s education, which, in turn, significantly impacts their children’s educational success. Simply put, parental SES determines how much parents can invest in their children’s education in terms of financial resources, energy, time, and attention. Although the five theories discussed above (family investment, social and cultural capital, resource dilution, and social causation theories) have different assumptions, their main theme remains the same, that is, the central role of parents in impacting children’s educational success. The findings of several prior studies are also congruent with the views expressed by these theories. Thus, high parental SES has an advantage over low parental SES. A very large body of literature has long documented the fact that children of parents with high SES outperformed those of parents with low SES (e.g., Lawson & Farah, 2017; Lyu et al., 2019; Morsy & Rothstein, 2015). This study posits that parental SES exerts a strong influence on school-age children’s educational success and is thus likely to translate into either educational truncation or success.

This study found that parental SES impacts the extent to which school-age children have a solid educational foundation. When children have a good foundation at an early age, they are more likely to have greater chances of succeeding in their pre-and post-secondary education. This assumption was also supported by Li and Qui (2018), who found that education has a continuous and accumulative nature, that is, it is a continuous process in which success in the previous stage affects that in subsequent stages. When children do not have a solid foundation at an early age, their willingness and ability to pursue their studies will decline. This, in turn, will increase their intention to leave school for good. When they leave school before completing their secondary or post-secondary level, they are more likely to face severe difficulties in finding work and thus become a burden to their country (Carnevale et al., 2012; Psacharopoulos, 2006). Conversely, when students have a good foundation at their age, they are more likely to continue their education (pre-and post-secondary) and can have appropriate credentials, which will subsequently increase their employment opportunities.

The findings show that when compared to children of parents with high SES, those of parents with low SES tend to find it difficult to move from one level of education to the next as they do not have a solid educational foundation. Research has also shown that the first few years of a child’s life are vital for the development of social skills and language (Francesconi & Heckman, 2016; Gardner-Neblett & Iruka, 2015), which are also impacted by parenting practices and SES (Kalil & Deleire, 2004; Pong et al., 2010). The current study argues that inequality of education starts early on in life and extends into adolescence and young adulthood. Aikens and Barbarin (2008) found that the further children fall behind, the more difficult it is for them to catch up. Thus, they continue to fall behind. Educational problems of the children of parents with low SES can be compounded, which will also discourage them from succeeding at schoolwork. The top priority of low SES parents is providing their children food, shelter, and safety, and education takes a backseat. Their children are at risk for not having a solid educational foundation, which also forces them to struggle at school. A close look at the school life of children from low SES backgrounds reveals that they have several problems and challenges.

The graduation rate (high school and college) serves as an indicator of the impacts of parental SES on education. According to the National Student Clearinghouse (2019), while 69 percent of students from high-income high schools enrolled in college immediately after graduation, only 55 percent from low-income high schools enrolled in college immediately after graduation. Once enrolled, while 89 percent of students from high-income high schools returned to college in their second year, only 79 percent from low-income high schools returned to college in their second year. Whereas 51 percent of the high-income high school graduates completed college within 6 years, only 24 percent of the low-income high school graduates completed college within 6 years. These figures provide deeper insights into the existing achievement gap. The above figures suggest that students from low SES backgrounds are more likely to lack a good educational foundation at an early age and their problems will accumulate as they progress. These figures show that the gap in the educational success that exists between children from low and high SES backgrounds widens as they move on to higher grades, and subsequently, into employment. The current study argues that the unequal distribution of educational success between children of high and low parental SES remains one of the significant sources of social inequality.

The comparison of unemployment rates for educated and uneducated individuals serves as an indicator of the impact of education on employment. Whereas the unemployment rate for Americans with less than a high school diploma was 5.4 percent, those for high school graduates and bachelor’s degree holders and above were 3.8 percent and 2.0 percent respectively, as of May 2022 (The Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). These data suggest that those with education beyond high school tend to have greater employment opportunities. Another indicator of the impact of education on employment is the job projection results that, by 2020, 65 percent of the US jobs will require post-secondary education beyond high school (Carnevale et al., 2013). Carnevale & Cheah (2015) pointed out that over a lifetime, college graduates earn about USD 1 million more than high school graduates. These figures indicate that if individuals are to have a bright future or higher employment prospects, they must have post-secondary education. A college degree is a prerequisite for a growing number of jobs (Gowan, 2022; Kochhar, 2018; Lussier & Hendon, 2017) as most jobs require workers to acquire many attributes that are impacted by education. Education allows people to expand their KSAs and equip themselves better in an increasingly globalized labor market, which, in turn, enhances children’s future employment prospects.

As discussed above, individuals’ employment opportunities can be impacted by several factors, many of which are related to educational success. The more educated individuals are, the more likely they are to meet job requirements, and the more they meet the job requirements, the more likely they are to have better employment prospects. When individuals fail to complete their education successfully, they are more likely to face severe difficulties in finding work. The most popular theory that helps explain the link between education and employment is the human capital theory. This study argues that investments in education pay off in the form of higher future employment opportunities, as it opens doors to more jobs, and the differences in educational success can explain a significant part of the individuals’ variations in employment prospects and other outcomes (Carnevale & Cheah, 2015; Marginson, 2019). In the knowledge economy, which is an economic system in which the production of services and goods is based mainly on knowledge-intensive activities (Gowan, 2022; Lussier & Hendon, 2017), the contribution of post-secondary education to individuals, society, and the country at large is significant.

One of the main arguments of this study is that parental SES impacts children’s educational success and future employment prospects. Rivera (2015) found that many employers (e.g., investment banks, and consulting and law firms) favor job seekers from economically privileged backgrounds and give more weight to the economic, social, and cultural resources of the applicants and their parents. Class bias is built into American perceptions on the best and the brightest, and social status plays a significant role in influencing who reaches the top of the economic ladder (Rivera, 2015; Smith, 2017).

This study argues that although students from low SES backgrounds often have low academic performance, there are instances in which they can have high academic performance. One possible explanation for this is the presence of resilience factors, which help children from low SES backgrounds overcome risk factors that hurt their educational performance (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Friedman & Mandel, 2011; won Kim et al., 2017). For students with strong intrinsic motivation to learn and practice high self-control (self-discipline, self-regulation, and delay of gratification), the effect of parental SES on educational success is weakened. That is, as students have strong learning motivations and high degrees of self-control, they are more likely to overcome the unfavorable effects of low parental SES (Chen et al., 2018; Hoffmann et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020; Marks, 2006).

Conclusion

Several factors impact children’s future employment prospects. This study focused on one of them, namely the link between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects. It argued that as children’s future employment prospects are multi-faceted and complex, educational success can be used as a mediating factor between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects.

This study concluded that parental SES influences the quantity and quality of resources that parents devote to their children’s education, which, in turn, has a considerable effect on their children’s educational success. Education matters and has an essential role to play in a job search. Thus, it should not be a matter of choice but rather a requirement for individuals to succeed at the workplace.

This study highlights those parents with higher SES take advantage of their human, social, and cultural capital to enable their children to enjoy educational success and obtain higher levels of education, which will, in turn, improve their employment prospects. It shows that parental SES can either support children’s future employment by improving their academic success or inhibit it by adversely affecting their educational success. Thus, parental SES can be instrumental in enhancing or hindering children’s future employment. This does not mean that coming from a high SES background guarantees employment. However, coming from a low SES background indicates a greater likelihood of facing poor employment prospects. Parental SES is not a panacea to all problems of educational success and securing employment. However, it is one of the factors that influence educational success and employment prospects. This study argues that the prevailing disparities in children’s educational success are mainly because of the disparities in parental SES. The disparities in children’s educational success will impact their future employment prospects, and augment the widening gap between the rich and the poor.

This study has several important implications. Children are the citizens of tomorrow. Building a brighter future is possible if children are well educated, regardless of their SES. When children are well educated, they are more likely to succeed at the workplace and access better employment opportunities. It is in society’s interest to ensure that all children succeed at school, regardless of their SES. Children from low SES backgrounds can overcome challenges if:

1. Their parents help them have a solid foundation, which will keep them from falling behind. This is because once students begin to fall behind; it becomes hard to catch up. The educational success in each stage affects the performance in the subsequent stages.

2. Their parents become good role models and mold them appropriately from an early age onward.

3. Their parents get involved in their children’s school activities and set high educational expectations.

4. Their parents keep reminding them of the role of education in their future life and that education is the key to fulfilling their dreams and having a productive life.

5. Their parents provide educational guidance and support and assist them in improving their children’s self-discipline and self-regulation.

6. The government intervenes in children’s education by allocating sufficient resources to narrow down the achievement gap (e.g., after school tutorials, and extracurricular activities that have a positive impact on education). As explained by Gertler et al. (2014) many early child development programs (e.g., the Early Head Start program and the Nurse-Family Partnership) provide children with direct interventions and give their parents training in parenting skills. Policymakers should look for ways to assist children from low SES backgrounds.

7. Their teachers understand their situations and help them overcome the stigma of coming from a low SES background rather than reinforcing their low self-esteem, by providing they support and encouragement.

8. They have a strong learning motivation to learn and implement high levels of self-control.

Several studies have discussed the link between parental SES and children’s educational success. However, few have examined the link between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects. This study has extended the existing literature by explaining the link between parental SES and children’s future employment opportunities. It provides insights that are crucial for both researchers and practitioners. Future research should also be directed at conducting a longitudinal study as it can provide evidence of the extent to which parental SES is linked to children’s future employment prospects. Collecting data on children’s educational performance (e.g., kindergarten, elementary and secondary school, and/or post-secondary education) and future employment opportunities (at the workplace) is necessary. It would be interesting if research is conducted across several countries to determine the extent to which economic level and socio-cultural factors impact the link between parental SES and children’s future employment prospects.

References

Abruzzo, K.J., Lenis, C., Romero, Y.V., Maser, K.J., & Morote, E.S. (2016). Does Participation in Extracurricular Activities Impact Student Achievement?. Journal for Leadership and Instruction, 15(1), 21-26.

Aikens, N.L., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Socioeconomic differences in reading trajectories: The contribution of family, neighborhood, and school contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 235.

Almendarez, L. (2011). Human capital theory: Implications for educational development. In Belize Country Conference paper.

Becker, G.S. (1992). Human capital and the economy. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 136(1), 85-92.

Becker, G.S. (2009). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. University of Chicago press.

Becker, G.S., & Tomes, N. (1976). Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. Journal of political Economy, 84(4, Part 2), S143-S162.

Beffy, M., Fougere, D., & Maurel, A. (2012). Choosing the field of study in postsecondary education: Do expected earnings matter?. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(1), 334-347.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Benson, J., & Borman, G.D. (2010). Family, neighborhood, and school settings across seasons: When do socioeconomic context and racial composition matter for the reading achievement growth of young children?. Teachers College Record, 112(5), 1338-1390.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Berkowitz, R., Moore, H., Astor, R.A., & Benbenishty, R. (2017). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 425-469.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture (Vol. 4). Sage.

Bradley, R.H., & Corwyn, R.F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 371-399.

Brecko, B.N. (2004). How family background influences student achievement. In Proceedings of the IRC-2004 TIMSS (Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 191-205).

Carneiro, P.M., & Heckman, J.J. (2003).Human capital policy.

Carnevale, A.P., & Cheah, B. (2015). From hard times to better times: College majors, unemployment, and earnings. Georgetown University: Center on Education and the Workforce.

Carnevale, A.P., Smith, N., & Strohl, J. (2013). Recovery: Projections of jobs and education requirements through 2020. Washington, DC: Georgetown Public Policy Institute.

Carnevale, A.P., Rose, S.J., & Hanson, A.R. (2013). Certificates: Gateway to gainful employment and college degrees.

Chen, Q., Kong, Y., Gao, W., & Mo, L. (2018). Effects of socioeconomic status, parent–child relationship, and learning motivation on reading ability. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1297.

Choi, S., Taiji, R., Chen, M., & Monden, C. (2020). Cohort trends in the association between sibship size and educational attainment in 26 low-fertility countries. Demography, 57(3), 1035-1062.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Coleman, J.S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American journal of sociology, 94, S95-S120.

Conger, R.D., & Donnellan, M.B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 175.

Cunha, F., & Heckman, J.J. (2009). Investing in our young people. Investing in our Young People, 387-417.

Dang, H.A.H., & Rogers, F.H. (2016). The decision to invest in child quality over quantity: Household size and household investment in education in Vietnam. The World Bank Economic Review, 30(1), 104-142.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Davis, J., Wolff, H.G., Forret, M.L., & Sullivan, S.E. (2020). Networking via LinkedIn: An examination of usage and career benefits. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 118, 103396.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

De Graaf, N.D., De Graaf, P.M., & Kraaykamp, G. (2000). Parental cultural capital and educational attainment in the Netherlands: A refinement of the cultural capital perspective. Sociology of education, 92-111.

Eccles, J.S. (2005). Influences of parents' education on their children's educational attainments: The role of parent and child perceptions. London Review of Education.

Francesconi, M., & Heckman, J. J. (2016). Child development and parental investment: Introduction. The Economic Journal, 126(596), F1-F27.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Friedman, B.A., & Mandel, R.G. (2011). Motivation predictors of college student academic performance and retention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 13(1), 1-15.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gardner-Neblett, N., & Iruka, I.U. (2015). Oral narrative skills: Explaining the language-emergent literacy link by race/ethnicity and SES. Developmental psychology, 51(7), 889.

Garrett, R.J. (2020). Predictive Relationship between Undergraduate Program Configurations, Employment Readiness, and Receiving an Employment Offer (Doctoral dissertation, Grand Canyon University).

Gowan, M. (2022). Fundamentals of HR Management for Competitive Advantage.

Harvey, L. (2000). New realities: The relationship between higher education and employment. Tertiary Education & Management, 6(1), 3-17.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hoffmann, R., Kröger, H., & Pakpahan, E. (2018). Pathways between socioeconomic status and health: Does health selection or social causation dominate in Europe?. Advances in Life Course Research, 36, 23-36.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hollingshead, A.B., & Redlich, F.C. (1958). Social class and mental illness: Community study.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jæger, M.M. (2012). The extended family and children’s educational success. American Sociological Review, 77(6), 903-922.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jiang, S., Li, C., & Fang, X. (2018). Socioeconomic status and children's mental health: Understanding the mediating effect of social relations in Mainland China. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(2), 213-223.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kalil, A., & DeLeire, T. (Eds.). (2004). Family investments in children's potential: Resources and parenting behaviors that promote success. Psychology Press.

Karagiannaki, E. (2017). The effect of parental wealth on children’s outcomes in early adulthood. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 15(3), 217-243.

Kim, C., Tamborini, C.R., & Sakamoto, A. (2015). Field of study in college and lifetime earnings in the United States. Sociology of Education, 88(4), 320-339.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Knouse, S.B., Tanner, J.R., & Harris, E.W. (1999). The relation of college internships, college performance, and subsequent job opportunity. Journal of Employment Counseling, 36(1), 35-43.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kochhar, R. (2018). The American middle class is stable in size, but losing ground financially to upper-income families. Pew Res. Cent.

Kraus, M.W., & Keltner, D. (2009). Signs of socioeconomic status: A thin-slicing approach. Psychological Science, 20(1), 99-106.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods. In Unequal Childhoods. University of California Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lawson, G.M., & Farah, M.J. (2017). Executive function as a mediator between SES and academic achievement throughout childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(1), 94-104.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Li, S., Xu, Q., & Xia, R. (2020). Relationship between SES and academic achievement of junior high school students in China: The mediating effect of self-concept. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2513.

Lussier, R.N., & Hendon, J.R. (2017). Human resource management: Functions, applications, and skill development. Sage publications.

Lyons, P., & Bandura, R. (2017). An expanded value of college GPA in recruitment? As related to US organizations. Development and learning in organizations: An International Journal.

Lyu, M., Li, W., & Xie, Y. (2019). The influences of family background and structural factors on children’s academic performances: A cross-country comparative study. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 5(2), 173-192.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mahoney, C.R., Taylor, H.A., Kanarek, R.B., & Samuel, P. (2005). Effect of breakfast composition on cognitive processes in elementary school children. Physiology & Behavior, 85(5), 635-645.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Marginson, S. (2019). Limitations of human capital theory. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 287-301.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Marks, G.N. (2006). Family size, family type and student achievement: Cross-national differences and the role of socioeconomic and school factors. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 37(1), 1-24.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McMahon, W.W. (2009). Higher learning, greater good: The private and social benefits of higher education. JHU Press.

McMurray, S., Dutton, M., McQuaid, R., & Richard, A. (2016). Employer demands from business graduates. Education Training.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Merritt, J. (2016). What’s is an MBA really worth? Business Week, 99-102.

Milne, A., & Plourde, L.A. (2006). Factors of a low-SES household: What aids academic achievement?. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 33(3).

Morgeson, F.P., & Nahrgang, J.D. (2008). Same as it ever was: Recognizing stability in the BusinessWeek rankings. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 7(1), 26-41.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Morsy, L., & Rothstein, R. (2015). Five Social Disadvantages That Depress Student Performance: Why Schools Alone Can't Close Achievement Gaps. Report. Economic Policy Institute.

Neppl, T.K., Senia, J.M., & Donnellan, M.B. (2016). Effects of economic hardship: Testing the family stress model over time. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 12.

Perrons, D., & Plomien, A. (2010). Why socio-economic inequalities increase? Facts and policy responses in Europe. European Union.

Phillips. J.M (2022). Strategic staffing. Chicago Business Press.

Pong, S.L., Johnston, J., & Chen, V. (2010). Authoritarian parenting and Asian adolescent school performance: Insights from the US and Taiwan. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34(1), 62-72.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Powell, M.A., & Parcel, T.L. (1999). Parental work, family size and social capital effects on early adolescent educational outcomes: The United States and Great Britain compared. Research in sociology of work, 1-30.

Psacharopoulos, G. (2006). The value of investment in education: Theory, evidence, and policy. Journal of Education Finance, 113-136.

Reardon, S.F. (2011). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. Whither Opportunity, 1(1), 91-116.

Rivera, L.A. (2015). Pedigree: How Elite students get elite jobs. Princeton University Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Roth, P.L., & Bobko, P. (2000). College grade point average as a personnel selection device: Ethnic group differences and potential adverse impact. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 399.

Sastry, N., & Pebley, A.R. (2010). Family and neighborhood sources of socioeconomic inequality in children’s achievement. Demography, 47(3), 777-800.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schultz, T.W. (1961). Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review, 51(1), 1-17.

Shah, M.A.A., & Anwar, M. (2014). Impact of Parent’s occupation and family income on Children’s performance. International Journal of Research, 1(9), 606-612.

Smith, E.J. (2017). Pedigree: How Elite Students Get Elite Jobs by Lauren A. Rivera. The Review of Higher Education, 40(2), 321-323.

Smits, J., & Ho?gör, A.G. (2006). Effects of family background characteristics on educational participation in Turkey. International Journal of Educational Development, 26(5), 545-560.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sullivan, A. (2002). Bourdieu and education: How useful is Bourdieu's theory for researchers?. Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences, 38, 144-166.

Tan, E. (2014). Human capital theory: A holistic criticism. Review of educational research, 84(3), 411-445.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Teachman, J. D., & Paasch, K. (1998). The family and educational aspirations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 704-714.

Vellymalay, S.K.N. (2012). The impact of parent's socioeconomic status on parental involvement at home: A case study on high achievement Indian students of a Tamil School in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 2(8), 11.

Walker, M. (2006). Towards a capability?based theory of social justice for education policy?making. Journal of Education Policy, 21(2), 163-185.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wang, L., Li, X., & Li, N. (2014). Socio-economic status and mathematics achievement in China: a review. Zdm, 46(7), 1051-1060.

Warner, W. L., Meeker, M., & Eells, K. (1949). Social Class in America: A manual of Procedure for the Management of Social Status. Oxford: Science Research Associates. In Chen, Q., Kong, Y., Gao, W., & Mo, L.(2018). Effect of Socioeconomic Status, parent-child relationship, and learning motivation on reading ability. Frontiers in Pscyhology, 9, 1297.

Wiederkehr, V., Darnon, C., Chazal, S., Guimond, S., & Martinot, D. (2015). From social class to self-efficacy: Internalization of low social status pupils’ school performance. Social Psychology of Education, 18(4), 769-784.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

won Kim, S., Kim, E.J., Wagaman, A., & Fong, V.L. (2017). A longitudinal mixed methods study of parents’ socioeconomic status and children’s educational attainment in Dalian City, China. International Journal of Educational Development, 52, 111-121.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yeung, R. (2015). Athletics, athletic leadership, and academic achievement. Education and Urban Society, 47(3), 361-387.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zhan, M. (2006). Assets, parental expectations and involvement, and children's educational performance. Children and Youth Services Review, 28(8), 961-975.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zhang, Y., & Xie, Y. (2016). Family background, private tutoring, and children’s educational performance in contemporary China. Chinese Sociological Review, 48(1), 64-82.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 08-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. ASMJ-22-12312; Editor assigned: 09-Jul-2022, PreQC No. ASMJ-22-12312(PQ); Reviewed: 19-Jul- 2022, QC No. ASMJ-22-12312; Revised: 25-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. ASMJ-22-12312(R); Published: 01-Aug-2022