Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

The Mediation Effect of Employees' Affective Organizational Commitment: The Impact of Employees' Perceptions of the Social Support for Training Programs on Enhancing Their Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Jordanian Hotels Sector

Ayman Mansour,Applied Science Private University

Hefin Rowlands,University of South Wales

Jassim Ahmad Al-Gasawneh,Applied Science Private University

Shaker Al-Qudah, Applied Science Private University

Hosam Shrouf, Applied Science Private University

Esra’a AlAmayreh, Applied Science Private University

Lama Ahmad Al-smadi, Applied Science Private University

Abstract

This study examined customer-contact employees’ attitudes and behaviors employed in Jordanian 1-5 stars hotels. It analyzed their perceptions of the acquired social support for training opportunities and the impact of such support on the service oriented-organizational citizenship behavior. An integrated conceptual model was developed to examine the effects of the social support for employees' training on their service oriented-organizational citizenship behavior, through investigating the mediating role of their affective commitment to their hotels. Using a sample of 450 front-line employees, Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) was conducted to test the hypotheses that were built based on the social exchange theory. The study's results show that social support for training programs helps employees engage in more service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors, and that employees' affective organizational commitment fully mediates this relationship.

Keywords

Social Support for Training (SST), Affective Organizational Commitment (AOC), Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB), Hotels, Jordan

Introduction

Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (OCBs) represent employees’ extra-role behaviors that are not expressly identified by a stipulated structured reward system in an organization. To put it another way, OCBs are the ways in which individual employees enthusiastically want to engage in work-related behaviors that benefit others (Jain, 2016; Chang et al., 2016). Several studies have examined the critical role that employees’ OCBs play in improving the organizational performance in different contexts (Andrew & Leo?n-Ca?zares, 2015; Chow, 2009; Bachrach et al., 2006), however, few studies have examined the impact of OCBs on service-oriented organizations (Krishnan et al., 2017).

Today's service organizations operate in a highly competitive and rapidly changing business environment marked by growing costs, dwindling capital, and demanding customers (Ocen et al., 2017; Percival et al., 2013; Diamantidis & Chatzoglou, 2012). Having a solid base of loyal and satisfied customers would enable these organizations to increase sales, increase market share, boost credibility, and increase profitability. In this respect, delivering superior quality services becomes critical to gaining consumers’ loyalty and satisfaction. Clearly, consumers’ loyalty and satisfaction are unquestionably important factors in identifying brand loyalty and decreasing customers' switching behavior, which eventually can enhance the competitive position of the organization (Tsiotsou, 2010; Ha & John, 2010).

Service delivery, as opposed to manufacturing, is dependent on contact employees' direct relationship with customers. Thus, customer assessment of service quality, organization’s image, and customers’ loyalty can all be influenced by the customer-contact employees’ attitudes, skills, and behaviors. Accordingly, front-line employees play a critical role in any service business, it is therefore critical for service organizations to find ways to motivate front-line employees to engage in OCB in order to fulfill or even exceed customers' service delivery expectations (Yang, 2012). In this respect, Bulut & Culha (2010) contended that the hotel industry as a labor-intensive service industry relies on the presence of high-quality individual employees to provide, operate, and handle tourism. Furthermore, employees' work-related behaviors play a significant role in achieving service quality and superiority, as well as keeping consumers satisfied and loyal.

Notably, it has been theoretically and empirically evidenced that employee training and the establishment of a supportive workplace environment where employees are largely supported and encouraged by their supervisors and colleagues to be more involved in training programs may play a crucial role in enhancing employees’ work-related attitudes (e.g. affective organizational commitment) from one hand (Bashir & Long, 2015; Newman et al., 2011; Bulut & Culha, 2010; Dhar, 2015; Bartlett & Kang, 2004), and work-related behaviors (e.g. organizational citizenship behavior) from the other (Krishnan et al., 2017; Mostafa et al., 2015; Ahmad, 2011).

Training can be seen as a high-investment human resource practice because it provides employees with ongoing opportunities to improve their skills and gain new knowledge, which helps to improve their workplace attitudes and behaviors (Fontinha et al., 2014). It is worth mentioning that supporting and motivating employees to engage in training programs offered by the organization, according to social exchange theory, can be interpreted by employees as an indication that the organization cares for them and recognizes their contributions to their workplaces. Therefore, according to SET, training opportunities are not limited to improving employee performance; rather, they often cover the socio-emotional aspects of the relationship between the organization and its employees. As a result, employees will pay off this investment by showing more Affective Organizational Commitment (AOC) to their organization as well as more Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) (Kloutsiniotis & Mihail, 2018; Bashir & Long, 2015; Allen & Shanock, 2013; Ehrhardt et al., 2011; Ng & Dastmalchian, 2011).

Even though previous research on HR practices, organizational commitment, and OCBs has helped to improve our understanding of these constructs. To the best of the authors' knowledge, no study has investigated the mediating effect of affective commitment on the relationship between the social support for employees’ training and OCBs in a service sector, especially in the Jordanian hotel’ sector. Accordingly, the aim of the current research is to empirically investigate the relationships among social support for training, employees’ affective commitment, and OCB in service context. In doing so, the current research attempts to examine how social support for training obtained from both supervisors and co-workers affect employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors through investigating the mediating role of the employees’ affective commitment in the Jordanian hotels.

Literature Review

Theoretical Background

Social Exchange Theory (SET) can be defined as ‘‘voluntary actions of individuals that are motivated by the returns they are expected to bring and typically do in fact bring from others’’ (Blau, 1964). SET has received a great deal of interest in management research, notably as a theoretical framework for interpreting organizational behavior and employment relationships (Latorre et al., 2016). SET, which plays a significant role in illustrating and managing the employment relationship between an organization and its employees, can predict several potential employee outcomes such as OCB, employees' affective organizational commitment, turn over intention, actual turnover, and job satisfaction (Wong & Wong, 2017; Chaudhry & Song, 2014; Buttner et al., 2010).

Researchers have used SET extensively to better understand various employees' work-related attitudes and behaviors. This theory is based on various disciplines such as sociology, social psychology, and anthropology, however, it may be claimed that this theory is also deeply rooted in the business environment (Reader et al., 2017). The exchange process is not limited to tangible goods, but also includes other intangible elements, such as, happiness, prestige, anger. Arguably, these elements can be considered more important than physical or tangible transactions and this can be attributed to the direct influence of these intangible elements on the power structure of the relationship between employing organization and employees (Lee et al., 2018).

According to SET, employees will be provided with training activities in order to initiate a social exchange of socio-emotional or affective resources, between an organization and its employees. In this regard, employees will regard training programs as organizational support, catalyzing them to respond positively to the support acquired from their organization, reflecting the positive perception that was formed on the part of employees towards their organization. This ultimately results in employees demonstrating a high level of AOC as well as OCB, because employees feel morally obligated to respond positively to an organization’s support. Therefore, it can be stated that employees' AOC and OCB are influenced by their perceptions of organizational support, which can be represented by the provision of training activities. Consequently, SET may provide a strong foundation for explaining the social support for training-OCB relationship, which explains the interpersonal interdependence and interaction among workplace collaborates (Cropanzano et al., 2001; Reader et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2016; Alcover et al., 2012; Zagenczyk et al., 2011; Pierce & Maurer, 2009; Pazy et al., 2006; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)

Two decades ago, researchers started focusing on the significance of OCB, since it contributes to promoting the overall organizational functioning (Paillé, 2012). OCB refers to employees’ work-related behaviors that influence positively and favourably the workplace or its members. Organ (1988) defines OCB as “individual behavior that is discretionary and not directly or explicitly recognized by formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes effective functioning of the organization” (p.4).

OCB represents employee’s voluntary behaviors that are not embedded in his/her required work and not involved in his/her legal employment contract, and they are helpful to the overall job performance. Clearly, OCB is employees' voluntary effort or non-compulsory role that are not part of their work obligations, but these voluntary efforts increase organizational effectiveness and success. Interestingly, employees who display high levels of OCB tend to be more involved in their workplace and more engaged in discretionary conduct in order to reciprocate the employing organization (Xerri & Brunetto, 2013; Organ et al., 2006).

Basically, OCB comprises of work-related behavior that can be utilized to elevate an organization’s effectiveness through strengthening and preserving the social system (Lau et al., 2016; Ng & Feldman 2011). In a similar vein, OCB is sometimes known as extra-role behaviors, prosocial behaviors, or contextual performances that are not stipulated explicitly in an employee’s job duties (Ng & Feldman 2011). Importantly, these extra-role behaviors have been theoretically and empirically evidenced to play an important role in facilitating both psychological and social contexts by which task performance within an organization can be supported (Organ, 1997).

Moreover, it has been reported that OCB contributes significantly to the production increase, promotes the service quality provided to the customers, enhances customer satisfaction, and lessens customer complaints (Yang, 2012; Podsakoff et al., 2000). In service organizations, employees who demonstrate high level of OCB are most probably tend to reciprocate trust with their customers that may eventually lead to increase customers’ satisfaction and loyalty (Sun & Lin, 2010). Obviously, OCB plays an important role in the success of an organization, therefore, there is a compelling need to understand why and how employees engage in OCB.

According to Organ (1988), OCB has been conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompasses of five dimensions, sportsmanship, altruism, conscientiousness, courtesy, and civic virtue. Although the construct validity and interrelations with important variables have been redefined, tested, and supported later by Van Dyne, et al., (1994), however, it has been argued that these five dimensions as a measurement scale were designed to measure the same core; the comprehensive construct of OCB (LePine et al., 2002). LePine, et al., (2002) found that these dimensions are statistically highly associated; moreover, the correlations between these dimensions and other work outcomes are to some degree analogous.

Moreover, the above measurement scale was designed to measure OCB in non-service industries, therefore, it is not suitable to measure the same construct in service industries where employees have intense interaction with their customers, and those customers have unique and unpredictable needs and desires that must be fulfilled (Krishnan et al., 2017; Wang, 2009; Arrowsmith & McGoldrick, 1996). Accordingly, it has been argued that employees in service organizations, in particular, customer-contact employees should be engaged in a special kind of OCBs, that is, Service Oriented-Organizational Citizenship Behavior (SO-OCBs) rather than only being engaged in the general form of OCB (Nasurdin et al., 2012; Bettencourt et al., 2001; Borman & Motowidlo, 1993).

In service organizations such as hotels, front-line employees have three primary responsibilities. First, they represent the organization to outsiders, which means their work-related attitudes and behaviors may have an impact on the corporate image. Second, they serve as a channel between the external environment and the service organization's internal operations by delivering information about customers’ desires and demands, and offering suggestions and recommendations for service developments. Finally, the well-mannered and responsive behavior positively influences service delivery, which eventually contributes to build a positive perception regarding service quality. Subsequently, service organizations are required to enhance service-oriented types of OCBs in order gain the competitive advantage (Yang, 2012; Wang, 2009; Bettencourt et al., 2001; Borman & Motowidlo, 1993).

Accordingly, Bettencourt, et al., (2001) created a measurement scale for SO- OCB to address the gap in the previous literature that failed to highlight the importance of customer-contact employees’ citizenship behaviors within the service context. This measurement scale encompasses three dimensions, namely, loyalty, participation, and service delivery; these customer-contact employees’ citizenship behaviors play a vital role in implementing service quality. Firstly, loyalty represents an employees’ faithfulness to his/her organization through promoting services to the customers. In addition, an employee with high level of loyalty OCB serves as a spokesperson for the organization’s goods and services as well as its image (Organ et al., 2006). In this regard, Organ, et al., (2006) stated that service workers with a high level of loyalty would most likely serve the organizations they work for, as they will speak up for their organization and defend any criticisms it might face through emphasizing the positive side of it while having a conversation with prospect customers.

Secondly, service delivery OCB means that the employee is responsible, responsive, and careful while providing the service to the customers and the activities surrounding it to avoid unnecessarily expected problems (i.e., customer complaints). Therefore, high commitment and responsibility by the employee will positively affect two main things; on-time-delivery and high levels of customer satisfaction (Organ et al., 2006; Posdakoff & MacKenzie, 1994). Thirdly, participation in OCB generally exceeds the formal job obligations and involves the discretionary behavior that improves the quality-of-service delivery; thus, it needs service employees’ robust self-development (Organ et al., 2006).

Social Support for Training (SST)

The provided social support from an organization to employees to be engaged in training programs in order to update employees’ skills, knowledge, and abilities may be reflected in an increased favorable employees' work-related attitudes and behaviors. Although employees may obtain this social support to be involved in training activities from several resources such as friends, family, indeed, literature has emphasized the importance of organizational agents (supervisors) and co-workers as an indispensable source of social support for employees to take part in different training courses enthusiastically and passionately. It has been argued that employees’ psychological and overall well-being, can be enhanced by the obtained social support from supervisors and co-workers, which eventually leads to ameliorate the organizational effectiveness (Silva & Dias, 2016; Dhar, 2015; Newman et al., 2011).

However, the lack of this social support may result in unfavorable work-related attitudes and behaviors such as frustration, dissatisfaction, decreased commitment, and lower OCB. The vertical and horizontal support for training represents the major dimensions of the required social support for employees to engage in training activities. More clearly, vertical social support reflects the support that employees obtain from supervisors, while horizontal social support reflects the support that employees obtain from their co-workers (Bulut & Culha, 2010).

Apart from the direction of the social support either vertical or horizontal, it has been claimed that employees’ decision to be involved in training activities relies largely on the social support for training from both directions (Noe & Wilk, 1993). The following two sections are a more detailed explanation of these two dimensions.

Perceived Supervisor Support for Training (PSST)

Supervisor support was defined as “the degree to which employees form impressions that their superiors care about their well-being, value their contributions, and are generally supportive” (Dawley et al., 2008). Supervisors who are responsible for appraising, managing, directing, and supporting their personnel can represent an organization’s agents. According to organizational support theory, the actions of an organization’s agents (supervisors) mirror the general organization’s intent. Thus, the social exchange relationship between individuals’ employees and their supervisors can be best predicted by the extent to which the supervisors socially support their subordinates. Consequently, the supervisor’s social support stimulates employees' positive attitudes and behaviors towards the organization (Bibi et al., 2018; Park et al., 2018; Casper et al., 2011; Simosi, 2012).

Perceived supervisor social support has gained growing interest by researchers and practitioners alike given its influence on several employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors including, AOC, OCB, employees’ turnover, job satisfaction, burnout, turnover intentions, employees’ retention (Bibi et al., 2018; Newman et al., 2011; Kuvaas & Dysvik, 2010; Dawley et al., 2008). Importantly, it has been theoretically and empirically evidenced that supervisor’s support and appreciation of employees creates a supportive climate within the workplace environment, which finally contributes significantly to the development of both employees’ AOC and employees’ OCB (Wei Tian et al., 2016; Nazir et al., 2016; Çakmak-Otluo?lu, 2012; Casper et al., 2011; Rousseau & Aubé, 2010; Dawley et al., 2008; Joiner & Bakalis, 2006; Dockel et al., 2006; Rhoades et al., 2001).

In the training context, the social support provided by supervisor to employees to be involved in training programs implies the degree to which supervisors urge and encourage employees to participate in different training activities offered by the organization. However, it has been argued that supervisor’s social support for training is not restricted to only urging and encouraging employees to take part in training activities, but also it extends to motivate employees to acquire and learn new skills and knowledge and properly transfer these acquired skills and knowledge back to their work settings (Bashir & Long, 2015; Newman et al., 2011; Bulut & Culha, 2010).

The employees’ perception of the social support for training offered by supervisors to upgrade their knowledge, skills, and abilities drive them to be psychologically and morally obligated to attend more training programs. This in turn improves their competencies that enable them to execute their assigned responsibilities and tasks by implementing new learned techniques to carry out their work and resolve problems related to their daily routines. In this respect, employees who participate in training programs will be highly recognized and appreciated by their supervisors (Bulut & Culha, 2010).

Perceived Co-Worker Support for Training (PCST)

Co-workers can be viewed as “employees’ colleagues who are at the same level of hierarchy and interact with them on work-related issues” (Rousseau & Aubé, 2010, p.324). While perceived co-worker support can be defined as “the extent to which one’s co-workers are helpful, can be relied upon in times of need, and are receptive to work-related problems” (Menguc & Boichuk, 2012, p. 1360).

Several forms of social support can be offered from co-workers to their colleagues such as work-related information provision, caring, tangible aid, and collaboration. These forms of social support that can be developed over time have gained an increased amount of attention in the organizational behavior literature due to its beneficial implications on the overall employees’ psychological well-being as well as job performance. In this vein, it can be said that co-workers social support represents a fundamental source of job resources that can be utilized to assist their counterparts to perform their tasks effectively and efficiently, especially, assigned duties with extraordinary job demands (Mayo et al., 2012; Sloan, 2012; Rousseau & Aubé, 2010).

Even though the social support from co-workers is regarded as informal support within the workplace environment as this support is not officially permitted or stipulated within the organization, indeed, this social support is more likely to be commenced and backed by co-workers themselves (Rousseau & Aubé, 2010). Employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors are likely to be positively influenced by the perceived co-workers’ social support, and this can be attributed to the comfortable work environment which would be created as a result of meeting employees’ socio-emotional demands including approval, belonging, esteem. Consequently, the fulfillment of employees’ social requirements of affiliation prompts employees to display positive attitudes and behaviors towards each other and eventually towards their organization, the place where employees start socially identifying themselves with (Charoensukmongkol et al., 2016; Lawrence & Callan, 2011; Bashir & Long, 2015; McCormack et al., 2006).

In the training situation, employees’ decision to take part in training activities is to great extent influenced by co-workers’ social support for training. Interestingly, the unquestionable social role that co-workers play in persuading or discouraging their counterparts to be involved in training activities has been well recognized in the training literature. Along with these lines, it has been revealed that co-workers social support for training is regarded as an influential antecedent of effective training transfer (Bashir & Long, 2015; Simosi, 2012; Chiaburu, 2010; Ahmad & Bakar, 2003; Noe & Wilk, 1993).

Affective Organizational Commitment (AOC)

Affective commitment mirrors an employee’s profound emotional bonds with the organization, which contradicts an employee's continuing his/her membership with the organization based on a feeling of obligation or staying at the organization for tangible returns (Kim & Beehr, 2020). AOC has been defined by Meyer & Allen (1991) as “the employee’s emotional attachment to, identification with and involvement in the organisation”. Thus, it can be said that employees who are affectively committed to their organization have a robust belief in their organization’s values, in addition to their sincere and constant willingness to exert extra efforts to achieve their organization’s goals (Meyer et al., 1993). In this vein, affective commitment is also known as psychological commitment, which refers to an employee's emotional and psychological connection to an organization (Allen & Meyer, 1990), and reflects both common interests and values (Mowday, 1998).

It has been argued that an employee’s work-related behaviors can be best predicted by the level of affective commitment s/he holds toward the organization (Meyer et al., 2002). Importantly, employees who are affectively tied to their organization tend to participate passionately in their organization’s activities and feel that they want to keep their employment membership with their organization (Xerri & Brunetto, 2013). Accordingly, AOC refers to the emotional desire an employee possesses to continue working in the organization because s/he chooses to do so, not because s/he feels obligated to (Lambert et al., 2015).

Moreover, employees with a high level of AOC are likely to be more loyal and dedicated since their strong emotional attachment toward the organization creates a stable sense of belonging to their workplace. Such belonging motivates them to be enthusiastically engaged in beneficial behaviors to the organization, even though these behaviors are not explicitly stated in their employment contract (Yang, 2012). Importantly, AOC plays an important role as a predictor of several highly significant work-related attitudes and behaviors, such as OCB, job performance, enhanced individuals' adaptability to organizational change, intent to leave, turnover behavior, absenteeism (Breitsohl & Ruhle, 2013; Neves, 2009; Su et al., 2009).

The Relationship between Social Support for Training and OCB

Previous research suggests that inimitable employees' competences, skills, abilities, and knowledge, which can be gained through various training programs, are considered important element in generating profits and maintaining a competitive advantage. This is especially true in service organizations, where interactions between employees and customers are clearly visible. Employees' work-related behaviors in such organizations can be regarded as one of the most important factors contributing to their performance. In this vein, it has been argued that training play a vital role in shaping employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors (Gope et al., 2018; Choi & Yoon, 2015; Sung & Choi, 2014; Díaz-Fernández et al., 2014; Zheng & Lamond, 2010).

There is clear evidence that organizational investments in training are effective in communicating to employees that they are among an organization's key assets, conveying to employees that the organization is pursuing a long-term relationship with them, and positively influencing their perceptions of organizational support. Subsequently, the employee feels valued, encouraging him or her to reciprocate with positive attitudes and behaviors such as higher OCB, increased employee affective commitment, and satisfaction (Wong & Wong, 2017; Chaudhry & Song, 2014; Shuck et al., 2014; Paille, 2013; Cho & Perry, 2011; Snape & Redman, 2010; Lam et al., 2009).

The above perspective can be backed by the findings of several empirical studies that established a positive relationship between training and its related aspects including, social support for training, availability of training, training-related benefits, motivation to learn from one hand, and different employees’ work-related behaviors such as employees’ OCB form the other (Ahmed, 2016; Ahmad, 2011; Noor, 2009; Ashill et al., 2006; Bolino & Turnley, 2003; Werner, 1994).

Following this line of thought, Nasurdin, et al., (2012) concluded that through training, customer-contact employees are likely to become highly motivated and able to engage in service-oriented behaviors that go beyond their formal responsibilities. Thus, training will foster more service-oriented OCB among employees. Likewise, it has been argued that service-oriented citizenship behaviors of customer-contact employees are positively affected by the perceived organizational support reflected by the provided training to the employees (Rubel & Rahman, 2018; Alfes, 2013; Wang, 2009).

Similarly, Ahmad (2011) concluded that social support for training contributes significantly to the development of employees’ OCB. Furthermore, Bolino & Turnley (2003) argued that training programs designed to foster relationships among co-workers or between supervisors and subordinates are required to raise the level of citizenship within the organization. Along with that, Wei, et al., (2010); Joireman, et al., (2006) reported that comprehensive training could contribute to employees demonstrating their willingness to OCB, which will eventually be positively reflected in an improved organizational performance. In addition, Mostafa, et al., (2015) concluded that training opportunities were positively correlated to employees’ AOC and OCB, and the relationship was more significant with employees’ OCB.

Furthermore, a Malaysian survey discovered that employee' attitudes toward training play a critical role in shaping OCB (Tang &Tang, 2012). Moreover, Krishnan, et al., (2017) concluded that management should provide appropriate training courses to new customer-contact employees to provide excellent customer service to improve employees' service-oriented OCB in Malaysian telecommunications and internet service provider organizations. Therefore, managers must prioritize training programs in order to instil favourable work-related behaviours in their employees (Narang & Singh, 2012). Based on the above literature, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Social support for training has a significant positive effect on employees’ organizational citizenship behavior.

The Relationship between Social Support for Training and AOC

Social support for training, whether vertical or horizontal, has been shown theoretically and empirically to be strongly linked to the most important employees' work-related attitudes, such as AOC and job satisfaction, while negatively linked to employees’ turnover, tension, and absenteeism. Moreover, employees may also use this support to improve the quality of their social networking within the organization by developing their positive attitudes toward their organizational agents (supervisors) and co-workers (Newman et al., 2011).

The majority of the literature devoted to studying the relationship between PSST and employees' AOC has been underpinned by the theoretical framework of social exchange theory. Clearly, an organization, for example, can be exemplified by its supervisors who interact directly with individual employees. Supervisors who are supportive make an effort to create a social exchange relationship with their subordinates. Supervisors attempt to fulfill their employees' socio-emotional needs by providing guidance, affiliation, emotional and psychological support. As a result, when employees consider their supervisors to be supportive of their contributions and accomplishments, they reciprocate by appreciating and valuing their organization, which can be translated by strengthened emotional ties to their organization (Park et al., 2018; Simosi, 2012; Newman et al., 2011).

The training literature has proven that the PSST has a positive effect on employees’ degree of affective commitment to their organizations. It can be argued that increased employee emotional ties to their organization can be achieved when employees perceive that their supervisors socially support them in participating in training programs. Therefore, establishing a positive environment within the organization, where all employees are motivated to participate in training programs by their supervisors, aids the organization in having employees with high levels of AOC (Bashir & Long, 2015; Almodarresi & Hajmalek, 2015; Dhar, 2015; Ashar et al., 2013; Newman et al., 2011; Bulut & Culha, 2010; Bartlett & Kang, 2004; Ahmad & Bakar, 2003; Bartlett, 2001).

With respect to the PCST, several empirical studies have generally supported the positive effect of coworker support for training on employees' AOC, despite the scarcity of these studies. Hence, it has been suggested that more empirical studies should be conducted to investigate the critical role that PCST can play in improving desirable employees' work-related attitudes (Bashir & Long, 2015; Maertz et al., 2007).

The training literature has found that PCST can play a significant role in the development and maintenance of employees’ AOC. As a result, it can be argued that enhanced employees' emotional commitment to their organization is dependent on the social support and encouragement they receive from their coworkers in order to participate in training programs provided by the organization. Essentially, establishing a positive environment within the organization in which all staff is encouraged by their coworkers to participate in training programs aids the organization in having employees with high levels of AOC (Bashir & Long, 2015; Newman et al., 2011; Bulut & Culha, 2010; Bartlett, 2001). Based on foregoing, the next proposed hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Social support for training has a significant positive effect on employees’ affective organizational commitment.

The Relationship between AOC and OCB

Although literature identified broad array of predictors of OCB, several empirical studies have concluded that attitudinal predictors (e.g., AOC) still represent the most consistent influential (Ng & Feldman, 2011). Literature suggests that employees who are affectively committed to their organizations have been found to display high level of OCB. In this respect, most empirical studies have revealed the positive association between AOC and OCB (Paillé, 2012). Meyer, et al., (2002) uncovered that AOC is strongly linked to OCB, attendance, performance. Reviewing the commitment literature revealed that employees who are emotionally committed to their organization are likely to uphold their organization’s strategic direction through displaying OCB and handling innovatively work-related issues (Xerri & Brunetto, 2013).

The relationship between AOC and OCB can be supported by the model which was developed by March & Simon (1958), that is, the inducements-contributions model. This model indicates that inducements are offered by an organization to its employees in order to enter and stay with the organization, whereas employees should significantly contribute to the overall organizational effectiveness through a remarkable performance at their workplaces. Furthermore, the said relationship has been theoretically supported by SET and its popular norm, that is, reciprocity (Blau, 1964).

According to SET, employees who perceive themselves as being supported, respected, and valued by their organization are more likely to reciprocate by showing emotional bonds and trust in their social exchange process with their organization (Blau, 1964). Taken together, the inducements-contributions model and SET indicate that employees who are emotionally attached to their organizations show a tendency to reciprocate to their organizations by showing high level of OCB (Ng & Feldman, 2011; Cropanzano et al., 2003).

Yang (2012) found that the five human resource practices positively correlated with employees’ AOC. Moreover, employees’ AOC in turn was positively connected to the frontline employees’ service-oriented OCB, and the relationship between human resource practices and employees’ service-oriented OCB was fully mediated by AOC. Likewise, Chang et al. (2016) concluded that OCB was positively affected by four human resource practices when employees have a high level of AOC. In which, the authors revealed that employees’ AOC can play a moderating effect in demonstrating OCB. In a similar vein, Grego-Planer (2019) concluded that the affective component of organizational commitment was positively and significantly correlated to OCB in both private and public organizations. Hence, the next hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Employees’ affective organizational commitment has a significant positive effect on their organizational citizenship behaviour.

Affective Organizational Commitment as a Mediator

The current research attempts to investigate the mediating effects of AOC on the relationship between SST and employees’ OCB, since this study endeavors to enhance the service-oriented employees’ OCB through integrating the SST and AOC. In this respect, literature that examined the relationship between training and its related aspects (e.g., social support) from one hand, and OCB from the other lacks consideration and scrutiny for the potential effects of moderation and mediation variables for such a relationship.

In addition, the previous literature argued that the relationship between training and employees’ OCB has been affected by several factors that need identification and further examining (Krishnan, 2017; Snape & Redman, 2010). One important mediator variable that needs to be examined in both human resource practices and organizational behaviour literature is employees’ AOC, since AOC has been shown to be affected by training and its related variables from one hand (Krishnan, 2017; Nasurdin et al., 2012 ; Ahmad, 2011), and employees’ OCB has been shown to be influenced by their level of affective commitment on the other (Grego-Planer, 2019; Chang et al., 2016;Yalabik et al., 2015; Yang, 2012).

More clearly, the decision to select employees’ AOC in the current research and investigate its mediating effect on the relationship between SST and their level of OCB can be justified based on the importance of employees’ AOC as an example of employees’ work-related attitudes which has been theoretically and empirically evidenced to be positively influenced by training in the first place (Bashir & Long, 2015; Newman et al., 2011; Bulut & Culha, 2010; Bartlett & Kang, 2004; Bartlett, 2001). Consequently, these enhanced work-related attitudes lead to improve work-related behaviours such as OCB, performance, productivity (Prottas et al., 2017; Dhar, 2015; Jain, 2016; Ng & Feldman, 2011).

From a methodological perspective, Baron & Kenny (1986) argued that when there are relationships between variables, such as between the independent variable and the dependent variable, between the independent variable and the mediation variable, and between the mediation variable and the dependent variable, the usage of the mediating variable could be justified. The current study found all relationships mentioned above. Accordingly, employees’ AOC as a mediator has been selected to act as a mediator between SST and their level of service-oriented OCB among customer-contact employees. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed based on the above literature:

H4: Employees’ affective organizational commitment mediates the relationship between Social support for training and organizational citizenship behavior.

Methodology

Sample and Procedures

In the current study, the data were collected from customer-contact employees in Jordan’s hotels. Choosing frontline hotels employees was suitable for examining the hypothesized relationships, and the decision to include this category of employees can be attributed to several motives. Specifically, front-line employees have regular interactions with hotels’ guests, in which they communicate with customers on a daily basis. In addition, customer-contact employees’ work-related behaviors play a critical role in formulating customers’ perceptions regarding the image of the hotel, the quality of the services provided, and the customer loyalty. The primary data for the current study was collected using a highly structured quantitative instrument, that is, questionnaire survey.

In this respect, online questionnaires was adopted to distribute the questionnaires to the respondents, this way entails questionnaires to be delivered and returned by electronic means through e-mails (Saunders et al., 2009). The online questionnaires were adopted as a method to distribute questionnaires due to the restrictions and lockdown imposed by the Jordanian government to reduce the spread of Covid-19. Concerning the questionnaire's pretest and fulfillment of the face and content validity requirements; the questionnaire was submitted to a panel of experts comprised of both high-profile academicians and hospitality industry in Jordan, and their comments were taken into consideration. The researchers had to contact the human resource departments in these hotels to get their approval to participate in the current study. Distribution of the questionnaires began at these hotels once the researchers obtained the approvals from all these hotels to be involved in the current study.

A pilot study was conducted by distributing (60) questionnaires randomly to some customer-contact employees. (42) Completed and filtered questionnaires were returned and screened for reliability analysis. All of the variables used exceeded 0.70 in terms of internal consistency (Cronbach's Alpha). The target population consists of (285) Jordanian 1-5 stars hotels, and the sampling frame consists of (13515) employees working at (285) Jordanian 1-5 stars hotels (Ministry of tourism and antiquities, 2020). The sample for this analysis was chosen using a stratified random sampling technique. This sampling technique was used for a variety of purposes, including improving the representation of a specific stratum (groups) within the sampling frame. In which the sample will accurately represent the entire population based on the stratification criteria (Zikmund et al., 2013). Moreover, this technique was used to resolve the variability in Jordanian hotel sizes, which had been determined by the total number of employees working in each hotel. More clearly, when the population as a whole has clearly different (groups) strata that are homogeneous in nature within the same strata, but there is heterogeneity or variability between these strata (groups), and in order to achieve simple randomized sampling, the researchers attempts to collect a similarly sized randomized sample from each (group) stratum separately in order to ensure that each (group) stratum is equally represented. Furthermore, this technique can be used to address the issue of inclusion of representatives of the whole population, whether it is overrepresentation or underrepresentation. Since stratified random is considered as a modification of random sampling by which the researcher is able to divide the target population into more than one significant and relevant group (strata) based on one or more than one attribute that characterizes this group (strata) (Saunders et al., 2009; Collis & Hussey, 2009).

The current study was carried out at the individual level of analysis that can be represented by the customer-contact Jordanian employees who work in the 1-5 stars Jordanian hotels and have undergone training programs in the past two years. This indicates that the current study excluded non-Jordanian employees. Selection of respondents was determined by each hotel, in which each hotel provided the researchers with employees list, and this list has the names of front-line employees who have experienced the training programs offered by their hotels in the past two years. The researcher selected a sample of employees at random from these lists and began sending questionnaires to those employees through e-mails. As a result, total number of (450) questionnaires were sent to frontline hotels employees (e.g., receptionists, food, and beverage servers). (231) questionnaires were retrieved after the filtration and screening process to eliminate any extreme and/or missing sections, indicating a response rate of 51.3%.

Measures

The development of the questionnaire was in accordance with 5-point Likert- scale grading, where 1 was strongly disagree and 5 was strongly agree. The questionnaire was divided into two sections; the first section was designed to measure the demographic characteristics of customer-contact employees, such as age, education, and years of experience. The second and most important section included questions that were developed to measure the study's major variables.

The variables under investigation were chosen from well-established and validated scales and classified into three groups, namely, SST as the independent variable, which was used as a multidimensional construct comprised of PSST and PCST. Service-oriented OCBs as the dependent variable that was considered as a multidimensional construct consists of loyalty OCB, participation OCB, and service delivery OCB. Finally, AOC as the mediating variable used as unidimensional construct.

The second and main part of the questionnaire includes SST as the independent variable, in which this variable divided into two sub-dimensions, namely, PSST, which was measured by six-item, and originally created by Noe & Wilk (1993) (α=0.96), and PCST which was measured by four-item scale and originally created by Noe & Wilk (1993) (α=0.83). Service-oriented OCBs which represent the dependent variable, were developed by Bettencourt et al., (2001), in which this variable divided into three sub-dimensions, namely, loyalty OCB was measured using a two-item scale (α=0.89), participation OCB was measured using a three-item scale (α=0.93), and service delivery OCB was using a three-item scale (α=0.92). The AOC as the dependent variable was measured by a 6-item scale and originally created by Meyer et al. (1993) (α=0.94).

Results

Measurements Model

AOC (first-order construct), SST (second-order construct), and OCB are the three main variables in this analysis (second-order construct). Two factors were used to evaluate SST, while three factors were used to evaluate OCB. OCB and SST were classified as a second-order reflective-reflective construct in this research. SST and OCB were found to be effective treatments for the second-order aspect in this research. This will help with the strategic and consensus dimensions of the project. In addition, the second order was used to reduce the number of relationships as well as the number of hypotheses that needed to be answered in the structural model. According to Hair, et al., (2016), such use facilitates the interpretation of the PLS path model. The two-stage method was used in this analysis. As a result, the repeated indicator technique was used in the first stage of this research. The first-order scores for first-order constructs were collected here, and the weighting of the first-order variables was used in the calculation of the second-order contract's CR and AVE in the second level.

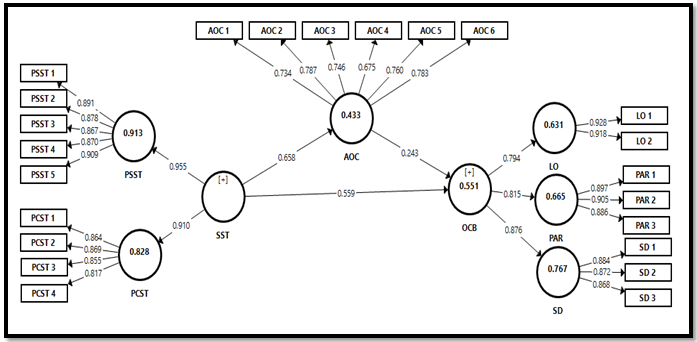

The measurement model was evaluated using convergent validity and discriminant validity in this analysis. The composite reliability, Average Variance Extract (AVE), and factor loading are all examined as part of the convergent validity evaluation. As a consequence, the results are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. As can be shown, each object had a loading greater than 0.5, with the exception of PSST 6, which had a loading of 0.226, which is less than 0.5 and was thus deleted; AVE and CR figures were both greater than 0.7.

| Table 1 Measurement Model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First order Construct | Items | Factor loading | CR | AVE |

| Perceived supervisor support for training (PSST) | PSST 1 | 0.891 | 0.947 | 0.780 |

| PSST 2 | 0.878 | |||

| PSST 3 | 0.867 | |||

| PSST 4 | 0.870 | |||

| PSST 5 | 0.909 | |||

| PSST 6 | 0.226 | |||

| Perceived co-worker support for training (PCST) | PCST 1 | 0.864 | 0.913 | 0.725 |

| PCST 2 | 0.869 | |||

| PCST 3 | 0.855 | |||

| PCST 4 | 0.817 | |||

| Affective Organizational Commitment (AOC) | AOC 1 | 0.734 | 0.884 | 0.560 |

| AOC 2 | 0. 787 | |||

| AOC 3 | 0.746 | |||

| AOC 4 | 0.675 | |||

| AOC 5 | 0.760 | |||

| AOC 6 | 0.783 | |||

| Loyalty (LO) | LO 1 | 0.928 | 0.920 | 0.852 |

| LO 2 | 0.918 | |||

| Participation (PAR) | PAR 1 | 0.897 | 0.924 | 0.802 |

| PAR 2 | 0.905 | |||

| PAR 3 | 0.886 | |||

| Service delivery (SD) | SD 1 | 0.884 | 0.907 | 0.675 |

| SD 2 | 0.872 | |||

| SD 3 | 0.868 | |||

| Second order constructs | ||||

| Social support for training (SST) | PSST | 0.955 | 0.930 | 0.870 |

| PCST | 0.910 | |||

| Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) | LO | 0.794 | 0.868 | 0.687 |

| PAR | 0.815 | |||

| SD | 0.876 | |||

The convergent validity evaluation HTMT assesses the model's discriminant validity (see Henseler, 2015), and the obtained HTMT construct values in this analysis were less than 0.90, with values ranging from 0.559 to 0.834. Table 2 summarizes the findings. As a result, each latent construct calculation in this study was exclusively discriminant against each other, according to Henseler, et al., (2015).

| Table 2 Discriminant Validity (HTMT) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOC | LO | OCB | PAR | PCST | PSST | SD | SST | |

| AOC | ||||||||

| LO | 0.628 | |||||||

| OCB | 0.702 | 0.819 | ||||||

| PAR | 0.605 | 0.525 | 0.834 | |||||

| PCST | 0.688 | 0.637 | 0.720 | 0.571 | ||||

| PSST | 0.707 | 0.694 | 0.773 | 0.594 | 0.827 | |||

| SD | 0.559 | 0.740 | 0.785 | 0.615 | 0.632 | 0.690 | ||

| SST | 0.730 | 0.702 | 0.784 | 0.609 | 0.661 | 0.571 | 0.695 | |

The convergent validity and discriminant validity analysis findings for the measurement model demonstrate the appropriateness and accuracy of the measurement scale in the assessment of the constructs and their relative objects in the CFA model. Consequently, Table 1 and Table 2 show the research findings for convergent validity and discriminant validity, respectively.

Structural Model

Hypothesized Direct Effects of the Constructs in the Structural Model

Table 3 shows that the SST predictor accounts for 43.3 % of the variation in AOC, while SST and AOC account for 55.1 % of the variation in OCB. The R2 values are greater than 0.19, according to Chin (2003). The Q2 value obtained by OCB (which is substantially greater than zero) is greater than zero. The test used to assess correlative fit suggests that the model has a reasonable degree of predictive relevance, and the model has a significant amount of predictive relevance. Hair (2019) recommended that the VIF values should be less than 5. The VIF values were 2.631, 2.223, and 3.121, respectively.

SST and AOC had p-values of 0.000 and 0.001 in prediction OCB, respectively, and SST had a p-value of 0.000 in prediction AOC. The odds of achieving by absolute p-value are 0.01 and 0.05, respectively. Furthermore, the path coefficient (S, B) values for (SST to OCB), (SST to AOC), and AOC to OCB were 0.559, 0.658, and 0.243, respectively, indicating positive relationships, which supports H1, H2, and H3.

| Table 3 Hypothesized Direct Effects Structural Model |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | St,β | St. d | R2 | Q2 | F2 | VIF | T-value | P-value | |

| H1 | SST>OCB | 0.559 | 0.093 | 0.551 | 0.236 | 0.067 | 2.631 | 6.010 | 0.000 |

| H2 | SST>AOC | 0.658 | 0.124 | 0.433 | 0.055 | 2.223 | 5.306 | 0.000 | |

| H3 | AOC>OCB | 0.243 | 0.075 | 0.041 | 3.121 | 3.229 | 0.001 | ||

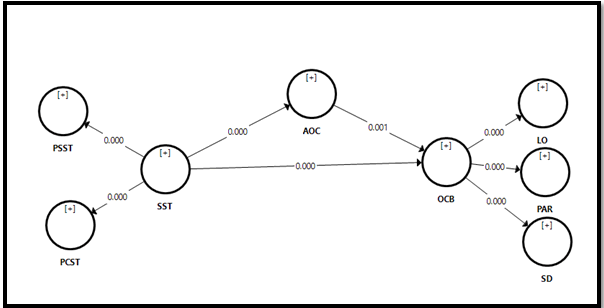

Indirect Effect of the Constructs

According to the results of Bootstrapping, the indirect impact of SST on OCB through AOC was positive and statistically significant at the 0.05 level;=0.160, T-value=3.181, P-value=0.002. Preacher & Hayes (2004) found that the indirect effect Boot CI Bias Corrected did not straddle a 0 in between, suggesting a mediation effect (LL=0.056, UL=0.255). The findings showed that the mediation effect was statistically important; indicating that hypothesis H4 was supported.

| Table 4 Results of Hypotheses Testing For The Mediation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PATH SHAPE | St.β | St. d | T values | 2.50% | 97.50% | p-values |

| SST>AOC>OCB | 0.160 | 0.050 | 3.181 | 0.056 | 0.255 | 0.002 |

Discussion and Conclusion

The current findings revealed that SST in both dimensions, vertical social support (PSST) and horizontal social support (PCST), has a positive and significant effect on improving employees' AOC in Jordan's hotel industry. These findings are in line with the findings of many empirical studies that investigated the relationship between the SST and employees’ AOC conducted in various work settings (Bashir & Long, 2015; Dhar, 2015; Newman et al., 2011; Bulut & Culha, 2010; Ahmad & Bakar, 2003; Bartlett, 2001).

This means that customer-service employees believe their supervisors socially promote and assist them in taking advantage of training programs, which in turn results in increased employees’ emotional ties to their hotels. Thus, this finding emphasizes the value of maintaining a positive working environment within an organization, where supervisors encourage and facilitate employees' involvement in training opportunities.

Moreover, these results highlighted the pivotal role of PCST for training in strengthening employees’ emotional ties to their organizations. Importantly, the current result is also consistent with an increasing body of literature on coworker social support in general and its critical role in enhancing employees' psychological well-being and performance, as well as improving employees' emotional bonds to their organizations. (Wei Tian et al., 2016; Mayo et al., 2012; Sloan, 2012; Tharenou, 1997; Noe & Wilk, 1993). PCST has been shown to foster employees’ positive work-related attitudes and behaviors by creating a supportive workplace environment. In which, employees’ socio-emotional needs such as belonging, esteem, and approval can be met by co-worker’s social support (Chiaburu, 2010).

With respect to the relationship between employees’ AOC and employees’ OCB, the results showed that employees, who are affectively committed to their organization and have a robust belief in their organization’s values, are more likely to energetically promote the organizational products and services. In addition, they make beneficial suggestions and contributions for service improvement. Irrespective of the nature of the work in this sector which includes dealing with several customers’ needs and requirements as well as working under pressure, employees with high level of AOC showed abnormal courteous and respectful to their customers.

Moreover, employees who have a strong sense of belonging to their hotels tend to voluntarily abide by customer service guidelines with intense care, in addition to innovatively contribute with creative ideas for customer promotions and communications. Although the service-oriented OCBs in this study has been conceptualized based on the work of Bettencourt, et al., (2001), it has been found that employees’ OCB was positively and significantly influenced by their level of emotional bonds toward their hotels, which confirmed the results of several empirical studies conducted in different work settings (Chang et al., 2016; Xerri & Brunetto, 2013; Yang, 2012; Ng & Feldman, 2011; Meyer et al., 2002).

The findings of this study suggest that employees’ perception of the SST that can be obtained from both supervisors and co-workers plays a crucial role in affecting contact employees’ citizenship behaviors. It was found that SST is positively and significantly correlated with employee’s service-oriented OCB. The current finding corresponds with several studies that investigated the potential role of the training and its related aspects and employees’ OCB (Krishnan et al., 2017; Nasurdin et al., 2012; Ahmad, 2011). Furthermore, this finding implies that customer-contact employees can easily use the SST that they can obtain from their supervisors and coworkers to attend various training programs to improve their work-related behaviors to be more considerate and respectful of customers, as well as to be more involved in promoting their hotel's services.

Moreover, the current finding suggests that if service firms are keen on increasing the level of their employee’s service-oriented OCB, they should create a supportive climate within the organization where customer-contact employees are encouraged by their supervisors and co-workers to be involved in training programmes. Therefore, to improve employees' service-oriented OCB, management should provide training courses to their new customer-contact employees on how to provide excellent customer service, and employees’ participation in these courses should be socially encouraged by supervisors and peers.

The finding that employees’ AOC was positively and significantly influenced by their perceptions of the SST obtained from their supervisors and co-workers indicates that their emotional attachments towards their hotels will be strengthened by their positive perceptions of the supportive environment within their hotels, where their participation in several training programs provided and funded by their employer are encouraged and supported by their supervisors and co-workers, This will be reflected in a higher level of service-oriented OCB among customer-contact employees.

Therefore, when employees’ AOC is improved due to the positive impact of the SST, this positive effect will be extended through employees’ AOC to enhance employees' service-oriented OCB. This finding suggests that encouraging and supporting customer-contact employees to be involved in training programs paves the way for those employees to be more emotionally attached to their hotels. Subsequently, employees would reciprocate in the form of improved service-oriented OCB, in which they will be voluntarily encouraged to embrace and incorporate new ideas for consumer promotions and communications, to vigorously promote their hotels products and services, and to make useful suggestions and contributions for service enhancement.

In light of this finding, the current findings lend strong support to the theoretical foundation of the current study; SET and its popular norm “reciprocity”. Clearly, social support for customer-contact employees to participate in training opportunities aims not only to improve their performance and productivity, but also to establish a social exchange relationship between an employee and his or her hotel. According to SET, an organization's investment in their employees' training can be used as a mechanism to catalyze the sense of employees’ obligation to positively discharge this investment by demonstrating high levels of affective commitment to their organization as well as high levels of OCB.

Limitations and Future Work

Since the samples were drawn exclusively from Jordanian hotels, there might be cultural limitations, which future studies may avert by investigating different cultural contexts. Another limitation in terms of cross-sectional data that can be interpreted by the causality path. In which no conclusions can be made about the direction of causality between study variables. Despite the fact that the results of this study and its hypotheses, which are based on existing literature are quite consistent, it is difficult to rule out the possibility that the causality between the study variables works in the opposite direction of what has been assumed. Accordingly, longitudinal research design should be considered by researchers in future research in order to solve the issue of causality.

This study gives some research directions for the future, in which researchers may replicate the current research using other employees' work-related behaviors (e.g., performance) to look for other possible outcomes of employee training. In addition, other mediating variables, as well as the function of moderating variables, must be considered by researchers when investigating the relationship between SST and their OCB. Moreover, the data for this study were collected from contact employees in Jordanian hotels, and it would be useful to replicate the study in other service industries to test the generalizability of the results. Importantly, future studies may look at the impact of another independent variable related to human resource bundles to better understand the relationship between other HR practices from one hand and affective commitment and OCB in the workplace from the other. Furthermore, examining the effect of employees' OCB on other outcome variables will be useful for future studies, as the literature emphasizes that OCB is an important predictor of many highly relevant work outcomes, such as absenteeism, turnover, and job performance (Breitsohl & Ruhle, 2013; Neves, 2009; Su et al., 2009).

References

- Ahmad, K.Z., & Bakar, R.A. (2003). The association between training and organizational commitment among white?collar workers in Malaysia.International journal of training and development,7(3), 166-185.

- Ahmad, K.Z. (2011). The association between training and organizational citizenship behavior in the digital world. Communications of the IBIMA, 11(20), 1-17.

- Ahmed, N. (2016). Impact of human resource management practices on organizational citizen-ship behavior: An empirical investigation from banking sector of Sudan. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(4), 964-973.

- Alcover, C.M., Martinez-Inigo, D., & Chambel, M.J. (2012). Perceptions of employment relations and permanence in the organization: Mediating effects of affective commitment in relations of psychological contract and intention to quit. Psychological Reports, 110(3), 839-853.

- Alfes, K., Shantz, A.D., Truss, C., & Soane, E.C. (2013). The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement, and employee behaviour: A moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(2), 330-351.

- Allen, D.G., & Shanock, L.R. (2013). Perceived organizational support and embeddedness as key mechanisms connecting socialization tactics to commitment and turnover among new employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(3), 350-369.

- Allen, N.J., & Meyer, J.P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of occupational psychology, 63(1), 1-18.

- Almodarresi, S.M., & Hajmalek, S. (2015). The effect of perceived training on organizational commitment.International Journal of Scientific Management and Development,3(12), 664-669.

- Andrew, S.A., & Leo?n-Ca?zares, F. (2015). Mediating effects of organizational citizenship behavior on organizational performance: Empirical analysis of public employees in Guadalajara, Mexico. EconoQuantum, 12(2), 71-92.

- Arrowsmith, J., & McGoldrick, A.E. (1996). HRM service practices: Flexibility, quality, and employee strategy. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 7(3), 46–62.

- Ashar, M., Ghafoor, M., Munir, E., & Hafeez, S. (2013).The impact of perceptions of training on employee commitment and turnover intention: Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 3(1), 74-88.

- Ashill, N., Carruthers, J., & Krisjanous, J. (2006). The effect of management commitment to service quality on frontline employees' affective and performance outcomes: An empirical investigation of the New Zealand public healthcare sector. International Journal of Non-profit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 11(4), 271-287.

- Bachrach, D.G., Powell, B.C., Bendoly, E., & Richey, R.G. (2006). Organizational citizenship behavior and performance evaluations: Exploring the impact of task interdependence. Journal of applied psychology, 91(1), 193-201.

- Baron, R.M., & Kenny, D.A. (1986).The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

- Bartlett, K.R. (2001). The relationship between training and organizational commitment: A study in the health care field.Human resource development quarterly, 12(4), 335-352.

- Bartlett, K., & Kang, D.S. (2004). Training and organizational commitment among nurses following industry and organizational change in New Zealand and the United States.Human Resource Development International,7(4), 423-440.

- Bashir, N., & Long, C.S. (2015). The relationship between training and organizational commitment among academicians in Malaysia.Journal of Management Development, 34(10), 1227–1245.

- Bettencourt, L.A., Gwinner, K.P., & Meuter, M.L. (2001). A comparison of attitude, personality, and knowledge predictors of service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of applied psychology, 86)1(, 29-41.

- Bibi, P., Ahmad, A., & Majid, A.H.A. (2018). The impact of training and development and supervisor support on employee’s retention in academic institutions: The moderating role of work environment. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 20)1(, 113-131.

- Blau, P.M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Bolino, M.C., & Turnley, W.H. (2003). Going the extra mile: Cultivating and managing employee citizenship behavior. The Academy of Management Executive, 17)3(, 60-71.

- Borman, W.C., & Motowidlo, S.M. (1993). Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In Schmitt, N., & Borman, W.C. (Editions.), Personnel Selection in Organizations, pp. 71-98.

- Breitsohl, H., & Ruhle, S. (2013). Residual affective commitment to organizations: Concept, causes and consequences.Human Resource Management Review,23(2), 161-173.

- Bulut, C., & Culha, O. (2010). The effects of organizational training on organizational commitment.International journal of training and development,14(4), 309-322.

- Buttner, H., Lowe, K.B., & Billings?Harris, L. (2010), Diversity climate impact on employee of color outcomes: Does justice matter? Career Development International, 15(3), 239-258.

- Çakmak-Otluo?lu, K.Ö. (2012). Protean and boundaryless career attitudes and organizational commitment: The effects of perceived supervisor support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 638-646.

- Casper, W.J., Harris, C., Taylor-Bianco, A., & Wayne, J.H. (2011). Work–family conflict, perceived supervisor support and organizational commitment among Brazilian professionals. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(3), 640-652.

- Chang, K., Nguyen, B., Cheng, K., Kuo, C.C., & Lee, I. (2016). HR practice, organizational commitment, and citizenship behavior. Employee Relations, 38(6), 907-926.

- Charoensukmongkol, P., Moqbel, M., & Gutierrez-Wirsching, S. (2016). The role of co-worker and supervisor support on job burnout and job satisfaction. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 13(1), 4-22.

- Chaudhry, A., & Song, L.J. (2014). Rethinking psychological contracts in the context of organizational change: The moderating role of social comparison and social exchange. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(3), 337–363.

- Chiaburu, D.S. (2010). The social context of training: Coworker, supervisor, or organizational support?”. Industrial and commercial training, 42(1), 53-56.

- Chin, W.W. (2003). A permutation procedure for multi-group comparison of PLS models. In: M. J. Vilares, M. Tenenhaus, P.S. Coelho, Esposito-Vinzi, V., & Morineau, A. (Editions), PLS and related methods, PLS’03 international symposium – Focus on customers (33–43). Lisbon: Decisia

- Cho, Y.J., & Perry, J.L. (2011). Intrinsic motivation and employee attitudes. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 32(4), 382–406.

- Choi, M., & Yoon, H.J. (2015). Training investment and organizational outcomes: A moderated mediation model of employee outcomes and strategic orientation of the HR function. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(20), 2632-2651.

- Chow, I.H.S. (2009). The relationship between social capital, organizational citizenship behavior, and performance outcomes: An empirical study from China. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 74(3), 44.

- Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2009). Business research: A practical guide for undergraduate and postgraduate students. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M.S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874-900.

- Cropanzano, R., Byrne, Z.S., Bobocel, D.R., & Rupp, D.E. (2001).Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(2), 164–209.

- Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D.E., & Byrne, Z.S. (2003). The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 160–169.

- Dawley, D.D., Andrews, M.C., & Bucklew, N.S. (2008). Mentoring, supervisor support, and perceived organizational support: what matters most? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29(3), 235-247.

- Dhar, R.L. (2015). Service quality and the training of employees: The mediating role of organizational commitment.Tourism Management,46, 419-430. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.001

- Diamantidis, A.D., & Chatzoglou, P.D. (2012). Evaluation of formal training programmes in Greek organisations. European Journal of Training and Development, 36(9), 888-910.

- Díaz-Fernández, M., López-Cabrales, A., & Valle-Cabrera, R. (2014). A contingent approach to the role of human capital and competencies on firm strategy. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 17(3), 205-222.

- Dockel, A., Basson, J.S., & Coetzee, M. (2006). “The effect of retention factors on organisational commitment: An investigation of high technology employees”. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 4(2), 20-28.

- Ehrhardt, K., Miller, J.S., Freeman, S.J., & Hom, P.W. (2011). An examination of the relationship between training comprehensiveness and organizational commitment: Further exploration of training perceptions and employee attitudes.Human Resource Development Quarterly,22(4), 459-489.

- Fontinha, R., Chambel, M.J., & Cuyper, N.D. (2014). Training and the commitment of outsourced information technologies’ workers: Psychological contract fulfillment as a mediator.Journal of Career Development,41(4), 321-340.

- Gope, S., Elia, G., & Passiante, G. (2018). The effect of HRM practices on knowledge management capacity: A comparative study in Indian IT industry. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(3), 649-677.

- Grego-Planer, D. (2019). The relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors in the public and private sectors. Sustainability, 11(22), 6395. doi:10.3390/su11226395

- Ha, H.Y., & John, J. (2010). Role of customer orientation in an integrative model of brand loyalty in services.The Service Industries Journal,30(7), 1025-1046.

- Hair, J.F., Risher, J.J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C.M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. In European Business Review, 31(I1), 2–24. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 43(1), 115-135.

- Jain, A.K. (2016). Volunteerism, affective commitment, and citizenship behavior: An empirical study in India. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(3), 657-671.

- Joiner, T.A., & Bakalis, S. (2006). The antecedents of organizational commitment: The case of Australian casual academics. International journal of educational management, 20(6), 439-452.

- Joireman, J., Kamdar, D., Daniels, D., & Duell, B. (2006). Good citizens to the end? It depends: empathy and concern with future consequences moderate the impact of a short-term time horizon on organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1307– 1320.

- Kim, M., & Beehr, T.A. (2020). Empowering leadership: Leading people to be present through affective organizational commitment? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(16), 2017-2044.

- Kloutsiniotis, P.V., & Mihail, D.M. (2018). The link between perceived high-performance work practices, employee attitudes and service quality: The mediating and moderating role of trust. Employee Relations, 40(5), 801-821.

- Krishnan, T.R., Liew, S.A., & Koon, V.-Y. (2017). The effect of Human Resource Management (HRM) practices in service- oriented Organizational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB): Case of telecommunications and internet service providers in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 13(1), 67-81.

- Kuvaas, B., & Dysvik, A. (2010). Exploring alternative relationships between perceived investment in employee development, perceived supervisor support and employee outcomes. Human Resource Management Journal, 20(2), 138-156.

- Lam, W., Chen, Z., & Takeuchi, N. (2009), Perceived human resource management practices and intention to leave of employees: the mediating role of organizational citizenship behaviour in a Sino-Japanese joint venture, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(11), 2250-2270.

- Lambert, E.G., Griffin, M.L., Hogan, N.L., & Kelley, T. (2015). The ties that bind: Organizational commitment and its effect on correctional orientation, absenteeism, and turnover intent. The Prison Journal, 95(1), 135-156.

- Latorre, F., Guest, D., Ramos, J., & Gracia, F.J. (2016). High commitment HR practices, the employment relationship and job performance: A test of a mediation model. European Management Journal, 34(4), 328-337.

- Lau, P.Y.Y., McLean, G.N., Lien, B.Y.H., & Hsu, Y.C. (2016). Self-rated and peer-rated organizational citizenship behavior, affective commitment, and intention to leave in a Malaysian context. Personnel review, 45(3), 569-592.

- Lawrence, S.A., & Callan, V.J. (2011). The role of social support in coping during the anticipatory stage of organizational change: A test of an integrative model. British Journal of Management, 22(4), 567-585.

- Lee, J., Chiang, F.F., van Esch, E., & Cai, Z. (2018). Why and when organizational culture fosters affective commitment among knowledge workers: The mediating role of perceived psychological contract fulfilment and moderating role of organizational tenure.The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(6), 1178-1207.

- LePine, J.A., Erez, A., & Johnson, D.E. (2002). The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: a critical review and meta-analysis. Journal of applied psychology, 87(1), 52-65.

- Maertz, C.P., Griffeth, R.W., Campbell, N.S., & Allen, D.G. (2007). The effects of perceived organizational support and perceived supervisor support on employee turnover. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28(8), 1059-1075.

- March, J.G., & Simon, H.A. (1958). Organizations. New York: Wiley.

- Mayo, M., Sanchez, J.I., Pastor, J.C., & Rodriguez, A. (2012). Supervisor and co-worker support: A source congruence approach to buffering role conflict and physical stressors. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(18), 3872-3889.

- McCormack, D., Casimir, G., Djurkovic, N., & Yang, L. (2006). The concurrent effects of workplace bullying, satisfaction with supervisor, and satisfaction with co-workers on affective commitment among schoolteachers in China”. International Journal of Conflict Management, 17(4), 316-331.

- Menguc, B., & Boichuk, J.P. (2012). Customer orientation dissimilarity, sales unit identification, and customer-directed extra-role behaviors: Understanding the contingency role of co-worker support. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1357-1363.

- Meyer, J.P., Stanley, D.J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1) 20-52.

- Meyer, J.P., Allen, N.J., & Smith, C.A. (1993). “Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of applied psychology, 78(4), 538-551.

- Meyer, J.P., & Allen, N.J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment.Human resource management review,1(1), 61-89.

- Ministry of tourism and antiquities. (2020). http://www.tourism.jo/Default/En.

- Mostafa, A.M.S., Gould?Williams, J.S., & Bottomley, P. (2015). High?performance human resource practices and employee outcomes: the mediating role of public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 75(5), 747-757.

- Mowday, R.T. (1998). Reflections on the study and relevance of organizational commitment. Human resource management review, 8(4), 387-401.

- Narang, L., & Singh, L. (2012). Role of perceived organizational support in the relationship between HR practices and organizational trust. Global Business Review, 13(2), 239-249.

- Nasurdin, A., Ahmad, N., & Ling, T. (2012). Human resource management practices, service climate and service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: A review and proposed model. International Business Management, 6(4), 541-551.

- Nazir, S., Shafi, A., Qun, W., Nazir, N., & Tran, Q.D. (2016). Influence of organizational rewards on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Employee Relations, 38(4), 596-619.

- Neves, P. (2009). Readiness for change: Contributions for employee's level of individual change and turnover intentions. Journal of Change Management, 9(2), 215-231.

- Newman, A., Thanacoody, R., & Hui, W. (2011). The effects of perceived organizational support, perceived supervisor support and intra?organizational network resources on turnover intentions: A study of Chinese employees in multinational enterprises. Personnel Review, 41(1), 56–72.

- Ng, I., & Dastmalchian, A. (2011). Perceived training benefits and training bundles: A Canadian study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(4), 829-842.