Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 3

The Obligation of Bank to Provide Customer Financial Information due to Taxation: Violating of Bank Secrecy?

Theresia Anita Christiani, Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta

Chryssantus Kastowo, Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta

Abstract

The principle of bank secrecy is one of the basic principles animating bank’s relationship with customers and becomes the bank's obligation to protect it. The enactment of Law No.9 of 2017 authorizes the Directorate General of Taxes to directly request financial information data without permission from the Financial Services Authority. The consequence of the regulation is able to harm the existence of the banker-customer relationship which becomes the basis of the relationship and the essence in bank’s operational continuity. The emergence of public distrust to banking institutions as a result of the enactment of Law No.9 of 2017 must be prevented. The emerging legal problem are whether the obligation of banks to provide information on customer data for tax purposes does not violate the principle of bank secrecy and what efforts can be taken by banks in minimizing the potential adverse impacts of the regulations. Based on these findings, this normative research using secondary data as the main data resulted that exceptions to bank secrecy are only possible if they are intended to protect much higher level of interest, namely the country’s economic interests, than the interest of customers. Requiring banks to provide customer data information for tax purposes does not violate the principle of bank secrecy although it is a form of distortion of individual rights.

Keywords

Bank Secrecy, Customer Data Information, Tax Purposes

Introduction

The principle of bank secrecy is one of the relationships animating the bank and customer relationship. The purpose is to maintain customers’ trust to banks. The principle of bank secrecy provides an obligation for banks to maintain customer confidentiality. It is regulated in Law N.10 of 1998 concerning Amendments to Law No.7 of 1992 concerning Banking, and Law No.21 of 2008 concerning Sharia Banking. In Indonesia the bank secrecy implies the bank must keep the name of the customers and the amount of their deposit confidential. Schindelholz said that: Bank secrecy, which is not defined in any specific legal provision, is understood as being the banker is an obligation to keep confidential the facts learned in the course of banking activity (Dunant and Wassmer, 1998). The purpose of bank secrecy is to maintain public trust in banking institutions. Another goal is for the benefit of the community, as Gwendoline Godfrey said that:

“The rules around bank confidentiality continue to evolve, in many cases to the detriment of individuals but to the benefit of the public good” (Godfrey, 2016).

The enactment of Government Regulation in Lieu of Law No.1 of 2017, later becoming Law No. 9 of 2017, gives an obligation to Financial Services Authority to provide reports to the Directorate General of Taxes regarding financial information in accordance with the international agreement standard in taxation for each financial account identified as an account that must be reported. Both financial service institutions are also required to submit reports regarding financial information for taxation managed by the institution for a year. This regulation authorizes the Directorate General of Taxes to directly request financial information data without the permission of the Financial Services Authority.

The enactment of Law No.9 of 2017 has positive and negative consequences. Positive consequences of the validity of these regulations include the presence of banking system reforms, (Fabian et al., 2018). The negative consequence of the regulation is able to harm the existence of the banker-customer relationship becoming the basis of the relationship and the essence in the bank operational continuity. As Oberson notes that the more global the exchange of information, the greater risk of breaches of confidentiality, privacy ,and secrecy provision or even abuse in the rise of data obtained,(Stjepan & Irena, 2017). Negative consequences were also expressed by Avilliani (2018) who stated that regulations does not contain clarity to extent to which the Directorate General of Taxation can use the data and the sanctions for violator are still low (Avilliani, 2018). The emergence of public distrust to banking institutions as a result of the enactment of Law No.9 of 2017 must be prevented. The paper attempts to analyze two the legal problems, first: whether the obligation to provide customer data information by banks for taxation does not violate the principle of bank secrecy and second, what efforts can be taken by banks in minimizing the potential adverse effects of the regulations (Ying, 2015).

The significance of the legal problem in this paper is that the purpose of this regulation is preventing the movement of illicit money through bank institution but on the other hand it will create a distrust of the community towards bank institution. This is according to what was said by Jean-Rodolpho W.F: Countries cultivate a tradition of banking secrecy have to live with a new international order since the standards for exchange of information have been imposed them, not the exchange mechanism itself, which is not particularly effective and limited to defined request excluding fishing expeditions but the fear and insecurity that accompanied change of paradigm affected tax payer trust (Rodolpho, 2010). Although Switzerland has the reputation of being tax haven (Patrick, 2014) Switzerland has recently signaled a shift in its attitude to bank secrecy laws and it is ready to stop operating as a safe haven for unlawful wealth from corrupt political leader around the globe (Aubert, 1984).

Method Of Research

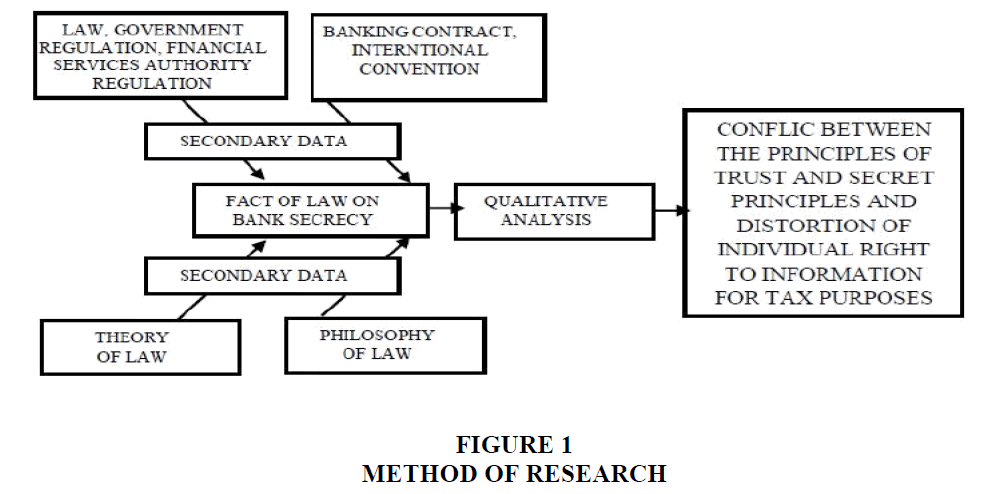

This paper is written from normative research that uses secondary data as the main data. Below is a flowchart showing the steps in conducting the research:

Figure 1 explains this research is doctrinal research which focuses on legislation that uses secondary data, namely primary (law, government regulation, FSA regulation) and secondary legal material (theory of law, philosophy of law). The data analysis technique used is qualitative data analysis.

The Basis of Bank and Customer Relationship

The existence of banking institutions is extremely significant in community. Banks are intermediary institutions for those lack funds and over-funded. Banker-customer relationship can be classified into contractual/explicit and non-contractual/implicit relationships. Contractual relationship is expressed in written form set forth in a standard agreement. On the other hand, non-contractual relationship is not expressed in written form. It is more to animate the bankercustomer relationship. This relationship includes trust, prudence and secrecy. Trust is the essence of banker-customer relationship. Only with the customer's trust, a bank’s existence is possible to maintain. Edward L. Symson said that the importance of public trust to banks had created a trust relationship between banks and their customers to be important (Sitompul, 2006).

In addition, the prudential relationship is usually associated with the way of banks’ fund placement to other parties in the form of loans, credit or other placements on the assets. The prudence is the main key for a bank to continue running its business, build and maintain public trust in banking institutions. Meanwhile, the secrecy gives the banks the obligation to maintain customer information. The secrecy between banks has been around for 400 years, as Edouard Chambost said: The most ancient hint of the secret bank can be found in the code of Hammurabi, a low book written, or rather carved, in stone 4000 years ago in Babylon. But the first controllable and uncommon secrecy provision is laid down in the rules of Banco Ambrosiano Milano of 1953. They say that the banker who violates his secret duty is loss his license. A similar clause adopted by the Hamburger Bank (Werner, 2014). This secrecy is a relationship underlying the banker-customer relationship as what Abdulah S said:

"The banks' duty of confidentiality is implied by the claim that it is difficult to set general dealing rules with confidentiality. In view of intense competition within the sector, a bank's profitability depends on its ability to maintain its reputation and inspire its customers with confidence. Confidentiality is implied therefore from the very beginning of the banker-customer relationship" (Abdulah, 2013).

Bank secrecy, an implicit relationship, requires banks to keep customer secrets owned by the bank. It does not emerge based on a written agreement between the bank and the customer but it animates the banker-customer relationship. Furthermore, confidentiality has later become an explicit legal term in the banker-customer contract (Abdulah, 2013). Since 1924 and based on the Decision of the Court of Appeal in Tournament National Provincial and Union Bank of England, confidentiality has been recognized as a fundamental pillar of the banker-customer relationship, existing as an implied term in the banker-customer contract (Stokes, 2011). In its development, this relationship is non-contractual, but able to be a contractual relationship because of the required normative provisions.

Bank Secrecy Regulation in Indonesia and Its Exceptions

Bank secrecy is regulated in Article 40 to Article 45 of Law No.10 of 1998 and Article 41 to Article 49 of Law No.21 of 2008. Banks are required to maintain the customers’ secrecy as Koslowski (2011) mentioned:

“Bank is obliged to maintain confidentiality about their business relationships with customers and about their customer accounts. They must preserve banking, secrecy or the banking secret (Bankgeheimnis) as it is called in German.”

The bank secrecy, according to Article 40 of Law No.10 of 1998 and Article 41 of Law No.21 of 2008, includes bank and affiliated parties that must keep the information about customers and their deposits, and also investors and their investments. According to R. Schindelholz, bank secrecy which is not defined in any specific legal provision is understood as being the banker’s obligation to keep confidential to facts learned in the course of banking activity. When a bank carries out the principle of bank secrecy, it can be noticed in several steps. The first step is whether the information provided by the bank is within the bank secrecy coverage. Then, the second step is whether the information is conveyed by parties prohibited by the applied legislation. The last step is if the information is included in the bank secrecy coverage, it must be investigated whether the information disclosure is not classified into exceptions justified by the legislation (Fuady, 1999). Bank secrecy in Indonesia adheres to a relative system in the sense that bank secrecy relating to customer data and the amount of the deposits can be disclosure for reasons authorized by law. These bank secrecy exceptions are in Article 41, Article 41A, Article 42, Article 42A, Article 43, Article 44, and Article 44A of Law No.10 of 1998 and Article 42 to Article 49 Law No.21 of 2008.

Bank Secrecy Regulation in Developing and Developed Countries

The secrecy of banking as one of the pillar of the functioning of the financial system has undergone major changes, even by countries that were previously known to maintain confidentiality. This right shows a very fundamental development. Information exchange is seen as one of the instruments to combat tax evasion (Marius, 2016). Lebanon as one the countries that had strict regulations of bank secrecy, but in its development adopted global regulations on money laundering. These adoptions of anti-money laundering regulations must be the first step that can form the basis for further amendments that might occur to reach the phase of softening the banking secrecy law without fear of losing the stability of the banking sector. Lebanon has sufficient reason to accept new values in respecting bank secrecy (Carole, 2016). Singapore has Bank secrecy regulations in the Common Law and Section 47 of Banking Act 18 which was passed in 1970 and revised in 1985. With that regulations Singapore is not recognizing as a tax heaven (Rodolphe, 2010). Bank secrecy according to the British Banking Regulation also states there is no absolutions regarding the principle of bank secrecy (Vishneskyi, 2015). An optimal balance is needed between personal and public interest.

The problem is the bank willingness to provide confidentiality to customer data and aspects of compliance with regulations is a dilemma. The state as a regulator should provide a balance between the interests of customer personally and the public interest (Husein, 2013).

Regulation on Financial Information Access for Taxation in Indonesia

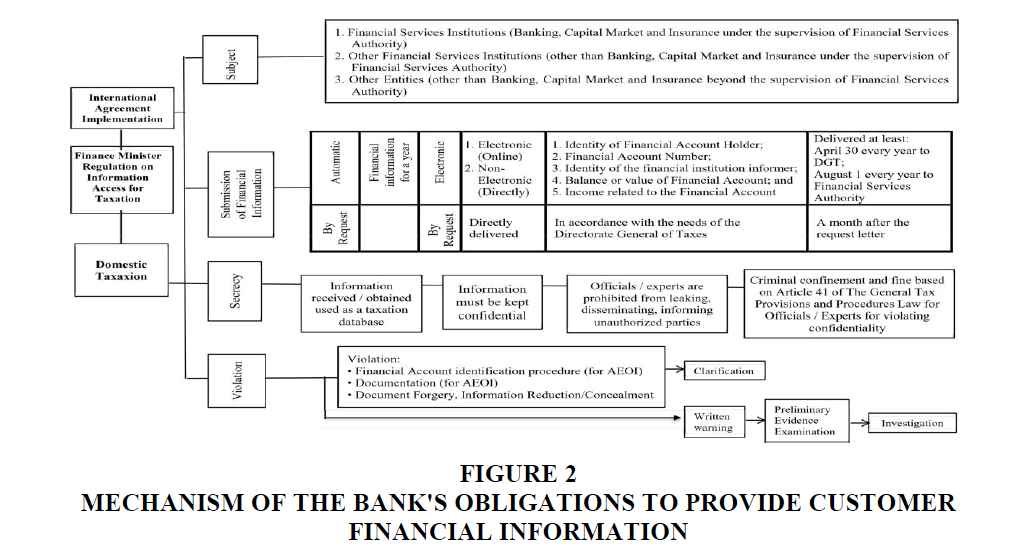

Access to Financial Information for Tax Purposes (Jane, 2015) as regulated in Law No.9 of 2017 is technically regulated in the Regulation of Finance Minister of Republic of Indonesia No.70 and 73/PMK.03/2017. This regulation basically contains the bank's obligations to provide customer financial information as described below (Sujarwadi, 2017):

Figure 2 explains that financial institutions including banks are required to provide financial information automatically or because of the request to the Directorate General of Taxation containing financial information in accordance with international agreement standards in taxation for each financial account identified to be reported. The matter happens that the report must be made by the bank and contains minimum information about the identity of the account holder, account number, financial services institution, account balance and income related to the financial account as the bank secrecy object (Mugarai, 2017). Before the existence of Law No.9 of 2017 and the Regulation of Republic of Indonesia No.70 and 73/PMK.03/2017/, the banking institution will issue a secret object of the bank if it gets permission from the FSA at the request of the Minister of Finance. These changes bring the potential for misuse of data by the directorate general of taxes and other parties. This will have negative impacts, namely the conflict between the principles of trust and the secret principles of the bank and cause distortion to individual rights.

The Obligation to Provide Customer Data Informaztion by Banks for Taxation after the Issuance of Law No.9 of 2017 does not Violate the Principle of Bank Secrecy

Bank is one of the financial institutions operating on the basis of public trust as stated by Alqayem: (2014) Banking operations based mainly on confidentiality are keys to a bank's activities. The implementation of the principle of bank secrecy is also an effort to maintain customer confidence. Indonesian regulation adheres to the principle of relative bank secrecy, meaning that bank secrecy is able to be breached with certain reasons. Taxation is one of the interests for bank secrecy breach by the permission of Bank Indonesia at the request of the Finance Minister. The difference after the regulation on Access to Financial Information for Tax Purposes is that bank is not obliged to keep the secrecy of information of customers and their deposits, and investors and their investments as long as it relates to access to financial information for tax purposes. After the regulation on access to financial information for tax purposes, the banking institutions are given the obligation in providing reports either automatically or upon a request to the Directorate General of Taxes, without necessarily through Financial Services Authority regarding objects to be reported. The coverage of bank secrecy relating to understanding, objects and exceptions (beside taxation) is still applicable in the relationship between the customer and the bank.

Efforts that can be taken by bank in minimizing the potential adverse effects of Law No. 9 of 2017 are proposed two methods. The methods are named by explicit and implicit methods which will be explained as below.

Method to Approach Bank Secrecy Relationship as Efforts to Minimize Adverse Effects

In the UK, the duty of secrecy is implicit in every agreement between banks and implied duties (Pramono, 2017). Duty secrecy is a non-contractual relationship between a bank and its customers. The consequence of disobedience in implementing the principle of secrecy by banks ruins the trust of public as customers towards banking institutions. It is extremely risky for the bank operational continuity. Learning from developed countries, the United Kingdom believes bank secrecy is not only limited to customer account information, but also about all 6 Information from the customer's account and obtained by the bank before and after the banker-customer legal relationship (Pramono, 2017). The understanding the bank secrecy coverage in England is certainly broader than the bank secrecy objects in Indonesia.

Based on the above description, before the enactment of Government Regulation in Lieu of the Law No.1 of 2017 later becoming Law No.9 of 2017, the Directorate General of Taxation had limited access to financial institutions, both banks and non-banks. After the enactment of Government Regulation in Lieu of the Law No.1 of 2017 later becoming Law No.9 of 2017, bank has an obligation to report to the Directorate General of Taxation. It contains financial information in accordance with the international agreement in taxation for each financial account identified as a must-be-reported account. Financial service institutions are also required to report related to financial information for tax purposes managed by financial service institutions for one year. This situation will indeed cause tension for banker-customer relationship due to bank's obligation to report on the customer's financial information in which the objects are the opposite of the provisions in the Banking Law and Sharia Banking Law. On the other hand, the enactment of Law No.9 of 2007 is understood to be based on greater interests aimed at the society welfare. Thus, the enactment of Law No.9 of 2017 will indeed affect banker-customer relationship since the previously confidential information becomes the mandatorily reported information by the bank to the Directorate General of Taxes.

Adverse influences possibly emerging in the enactment of bank obligations to banker-customer relationship can be minimized by explicit and implicit methods.

Explicit Method

The method to approach the customers on bank's obligation to report the customer's financial information must be explicitly stated in each banker-customer agreement. Legal banker-customer relationships are always conducted in standard written agreements. In relation to the implementation of the financial institutions’ obligation in reporting financial information to the Directorate General of Taxes, the law-base obligations must be informed to customers as outlined in the banker-customer agreement. If the agreement has been prepared by the bank, there is an obligation for the bank to ensure that it is well received by the customers. So, the customers’ awareness in determining the use of banks as alternative financial services evokes.

Implicit Method

Secrecy is an unwritten concept on banker-customer relationship, but animates the relationship. However, the spirit is as important as the written-form banker-customer relationship. By implementing this concept, the secrecy of customer’s financial information reported by bank is ensured both by bank obligation d to report and the Directorate General of Taxes. Shortly, there will not be misuse of the information both internally and externally as it is possibly to jeopardize confidential relationships as non-contractual relationships as the basic operation of bank.

Conclusion

Conclusion of this paper is first that the principle of bank secrecy is a legal obligation on a contractual relation basis as well as an ethical basis to the banker-customer relationship. It is a necessity given both juridical and ethical justification. The exceptions to bank secrecy are only enabled if intended to protect much more crucial interests, namely the State’s economic interests. Requiring banks to provide customer data information for tax purposes does not become a violation to the principle of bank secrecy although it is a kind of individual right distortion. Second, Efforts that can be taken by bank in minimizing the potential adverse effects of Law No. 9 of 2017 are proposed two methods. The methods are named by explicit and implicit methods.

References

- Abdulah, S. (2013). The bank's duty of confidentiality, disclosure versus credit reference agencies; Further Steps for consumer protection: Approval model. Journal of Current Legal, 19(4), 19-28.

- Alqayem, A. (2014). The banker customer confidential relationship. Retrieved November 25, 2018 from brunel.ac.uk

- Aubert, M. (1984). The Limits of Swiss Banking Secrecy under Domestic and International Law. International Tax and Buisness Law, 2(2), 273-297.

- Avilliani. (2018). Customer data disclosure policy is biased and potential to be abused. Probank, 128(36), 3-14.

- Carole, S. (2016). Anti-money laundering rules and the future of banking secrecy laws: Evidence from Lebanon. International Finance and Banking, 3(2), 148-160.

- Dunant, O., & Wassmer, M. (1998). Swiss bank secrecy: Its limits under Swiss and international laws. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, 20(2), 541-575.

- Fabian, M., Dewa, G., & Putu, N. (2018). Secret bank related to protection of customer’s data post published PERPPU Number 1 of 2017 concerning access to information for taxation interest. Universitas UdayanaBali.

- Fuady, M. (1999). Modern banking law. Bandung: Citra Aditya Bhakti Publisher.

- Godfrey, G. (2016). Bank confidentiality: A dying duty but not dead yet? Business Law International, 17(3), 173-215.

- Husein, Y. (2003). Bank privacy versus public interest secrets. Jakarta, Unpublished Thesis, Graduate Program of Universitas Indonesia.

- Jane, G.S. (2015). The end of secret Swiss accounts? The impact of the U.S. Foreign account tax compliance act (FATCA) on Switzerland's status as a haven for offshore accounts. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business, 35(3), 687-720.

- Koslowski, P. (2011). The banking secret, the right to privacy, and the banks’ duty to confidentiality. The Ethics of Banking, 30(1), 105-116.

- Marius, E.R. (2016). Bank secrecy: Pillar for performance of tax havens. Social Economic Debates, 5(2), 1-29.

- Mugarai, N. (2017). Tax havens off shore financial center and the current sanction regimes. Journal of Financial Crime, 24(2), 200-222.

- Patrick, E. (2014). The politics of financial intransparency: The case of banking secrecy. Swiss Political Science Review, 20(1), 146-164.

- Pramono, N. (2017). Law No. 9 of 2017 vs. bank secrecy. National Seminar on the Implementation of Law No.9 of 2017, Presented on the Seminar of Bank Secrecy, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia.

- Rodolphe, W.F. (2010). The end of banking secrecy in Switzerland and Singapore? International Tax Journal, 5(1), 38-57.

- Rodolpho, J.W.F. (2010). Exchange of tax information: The end of bank secrecy in Switzerland and Singapore. International Tax Journal, 2(1), 55-63.

- Sitompul, Z. (2006). Basic philosophy of the presence of the deposit insurance corporation. Surabaya: Airlangga University.

- Stjepan, G., & Irena, K. (2017). Effective international information exchange as a key element of modern tax system: promises and pitfalls of the OECD’s commons reporting standard. Public Sector Economi, 41(2), 207-226.

- Stokes, R. (2011). The genesis of banking confidentiality. The Journal of Legal History, 32(3), 279-294.

- Sujarwadi, N. (2017). Implementation of law no. 9 of 2017 in the perspective of principles of bank secrecy. Presented on The Seminar of Bank Secrecy, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia.

- Vishneskyi, A. (2015). Bank secrecy: A look at modern trends from a theoretical standpoint. Pravo Zhurnal Vysshey Shkoly Ekonomiki, 4(1), 140-146.

- Werner, D.C. (2014). Banking secrecy today. University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law, 10(1), 57-70.

- Ying, H. (2015). Bank Secrecy Symposium: Report of Proceedings. Centre for Banking & Finance Law. Retrieved from URL: http://law.nus.edu.sg/cbfl/pdfs/reports/CBFL-Rep-HY1.pdf