Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

The results of a primary research that investigated some aspects of conscious consumption among millennials and generation Z

Éva Pólya, Budapest Business School

Zoltán Máté, Budapest Business School

Abstract

Consumer consciousness have several aspects with totally different scopes, nevertheless different forms of consciousness can be characterized and well distinguished. In our paper we investigate members of Generation Z and Y (Millennials) and their relationship to conscious consumption. We introduce the main characteristics of these two generations, some important points where there is a difference among them during the purchase decision making process and somehow can be connected to consciousness. By several previous literatures the examined generations are more conscious environmentally and socially, hence we also introduce our findings about the attitudes and willingness to do for sustainability. We also investigated on what information sources the two generations base their conscious decisions to whom they listen to and via what type of media it is harder to get close to them. After a brief literature review the most important findings of our primary, quantitative research results are introduced highlighting the main similarities and differences between the two generations.

Keywords

Conscious Consumption, Millennials, Generation Z, Sustainable Consumption, Food Purchase Decision Making

Introduction

Different generations have individual expectations, experiences, values and lifestyles with different generational history and demographics that have an impact on their purchase behaviour. Hence marketing experts cannot treat them equally (Williams & Page, 2011). In our paper we focus on two generation Generation Y (Millenials) and Generation Z. These generations are referred frequently as digital natives. They have been growing up in a digital age, internet and social media is an organic part of their lives. This fact also influences their lifestyle and consumer habits, they like to do shopping more on mobile devices than on desktop computers. Upcycled food in not unknown for them, they would buy them for environmental reasons (Coderoni & Perito, 2021) the same as they would pay extra for green restaurants (Nicoleau et al., 2020), for organic foods (Molinillo et al., 2020) and for sustainable goods (Yamane & Kaneko, 2021). They internalized more the fact that the resources of the planet simply cannot be sustained without drastic changes in consumption level (Staniskis, 2012).

They have also experienced the recent recession after the COVID pandemic situation and the consequences of the global financial crisis in 2007. They are more concerned environmentally as climate change can influence their life in the future fundamentally; hence they are more open to conscious consumption.

Literature Review and Theoretical Background

Consumer Consciousness

Consumer consciousness occurs in nowadays trends as a phenomenon (Tör?csik, 2011, 2007, 2003). As consumers are willing to make optimal decisions, some form of consciousness can be observed among a wider range of consumers (Pólya, 2017). Consumer consciousness does not have a universal definition however it can be studied from different perspectives and aspects. In general, it is an umbrella term (Wong, 2019) covering awareness of how one’s consumption impacts society at large.

According to Dudás (2010) conscious consumption can be divided into two main parts as self-conscious consumption and responsible consumption. By this approach self-conscious consumption mostly includes health-, price-, value-, brand-, tendentiousness consciousness, knowledge of consumer rights and conscious financial actions while responsible consumption aim at society conscious consumption, environment conscious consumption and ethical purchase behavior (Rácz, 2013). All other type of consciousness can be somehow fitted to these frameworks.

According to Willis & Schor (2012) conscious consumption can be defined as “any choice about products or services made as a way to express values of sustainability, social justice, corporate responsibility, or workers’ rights and that takes into account the larger context of production, distribution, or impacts of goods and services”. By this definition they rather focus on mindful consumption considering then on how one’s actions as a consumer impact the environment and the welfare of other people (Carr et al., 2012). By Micheletti (2010) conscious consumer are disposed to spend more on items fitting to their ethos. According to Dudás (2011) somebody can be regarded as a conscious consumer to whom one or more characteristic true of the following:

1. He is aware of his consumer rights and also enforce them,

2. He is aware of the individual and/or social consequences of his decisions, and make choices consciously after sifting and careful consideration based on preliminary concepts,

3. Or he have recognized self-interests (e.g. health, safety, cost savings) and also expresses them in his purchasing decisions,

4. And/or he is willing to take into consideration ethical and (environmental, social and economic) sustainability aspects as well.

Generational Characteristics

Typical behavioral patterns of consumers can be characterized by their generational affiliation in many cases. Generations are often stereotyped, however we should not overlook the fact that today’s young generations prove to be a little different than the older generations of their age (Mcrindle & Fell, 2020). By defining generational cohorts, we can understand how changes over time (e.g., world events, technological, economic, social changes) have influenced people’s views of the world. Each generation has specific expectations, experiences, values, and lifestyles, with different generational histories and demographics that impact consumer behavior. Not all generations are the same; hence marketers cannot treat them the same way (Williams & Page, 2011). By their nature, generations are diverse, complex groups. Each generation has a specific set of values and attitudes that distinguish them from other generations (Boardman et al., 2020), so there is a difference in value orientation between each generation (Tör?csik, 2011). This difference in value orientation also highlights the lifestyle that members of each generation strive for and this effort determines how they spend or save. This is why each generation at the same age will behave differently as a consumer, which should not be ignored in the marketing planning process (Smith & Clurman, 2010).

Previous generations always have a significant impact on previous generations. The parent generation transmit the values, the belief system, the vision that play a significant role in how the younger generations interpret the world around them. The older generations have made the political decisions, created the technological innovations that affect the lives of present and future generations, they are the ones whose vision has created the social issues that future ones will struggle with (Seemiller & Grace, 2019). Obviously, no generation can be identified with a massive crowd of people behaving in exactly the same way, but rather a group of people born in a given period, comparable by age and life-cycle stage, and affected by events in a certain period (events, trends, developments, cohorts) (Ericson, 2019). Based on this, it can be clearly seen that the delimitation of generations is not clear, and as a result, there are minor differences between the individual authors. In all cases, the delimitation is based primarily on age and year of birth, but in fact all this is linked to turning points that have an impact on the individual's socialization and the beginning of employment (Tör?csik, 2011).

Generation Y, the Millennials also called as digital natives as they came of age with the computer (Sollohub, 2019) Generation Y already has an instinctive attitude towards technology, they are used to multitasking (Sujansky & Ferri-Reed, 2009), they use a wide range of digital media, they need interactivity in the creative activity (Reeves & Oh, 2008). They are tech savvy (Sujansky & Ferri-Reed, 2009; Spiegel, 2013), and show fascination for technologies (Howe & Strauss, 2000), have never met the word where extensive connectivity is not general. Millennials are the most mobile, they are always connected and do not separate from their mobile devices (Padveen, 2017). Due to this connectivity, they can quickly move en masse, even to totally unexpected directions (Tickell, 2018). They appreciate diversity, prefer to collaborate instead of being ordered, and are very pragmatic when solving problems (Lancaster & Stillman, 2002).

As a consumer Millennials are well informed, as never ever that amount of information were available before. Receiving honest reviews before purchasing is important them however they do not trust is traditional advertising channels, but they rather talk to one another (Padveen, 2017). They trust in word-of-mouth communication, suggestions and recommendations are more credible than classical commercial messages to them (Sujansky & Ferri-Reed, 2009). Moreover, they also want to give back to the community and support philanthropic causes, social responsibility is an important value to them (Spiegel, 2013).

Generation Z has been significantly impacted by growing cultural diversity, global brands, social media and the digital world. This generation is already growing into a work environment where robotics, automation, big data or Machine Learning is the mainstream. They are much more aware of global change, technological trends, or digital disruption. Compared to any previous generation, far the most change has taken place in their lives: they were born into the world of the internet, but they are already more shaped by mobile devices and social media. Social media is a defining field of their socialization- These platforms allowed them to connect with people like them with their own expression tools, their own content. It is already a truly global generation shaped by digital devices and growing connectivity (McCrindle, 2020). Technology is part of their life, they do not see technology as an instrument, and they value their connections the most. Their learning style is different, they focus on how the gain access to every piece of information, how to synthetize and integrate them into their life (Van Den Bergh & Behrer, 2016). Marketing to them also holds challenge: they prefer non-verbal communication, like emojis, GIFs, memes, they are not just using media, but produce and distribute content (Witt & Baird, 2018).

Research Methodology

Methodological Approach

Primary and secondary research was executed to base the findings of the authors. As empirical primary research, we conducted an online survey in 2021 April. Firstly, a data collection plan was outlined, later the questionnaire was developed and tested. The questionnaires were available in Hungarian and were executed in Hungary. The primary focuses of the investigation were the different aspects of consumer consciousness.

Single and multivariate statistical methods were used to process data using SPSS Statistics 27.0. In order to measure intention, we used 5-point Likert scales. Which is anchored at 1 for ‘to a very low extent’ and 5 for “to a very high extent’. After data collection data were cleaned. During the cleaning procedure missing data, normality, distribution and outliners were checked. Missing data rate was under five percent in each scale item. We interpret the results on the whole sample however we also highlight the uniqueness of the sub-samples that concentrates on the differences between generations.

Our main research questions were the followings:

Q1. In what aspects the two investigated generations can be considered conscious concerning food products?

Q2. Are there any correlation between commitment to sustainability and the scope of consciousness?

Q3. What type of information sources are the most prevalent in the case of conscious purchase decisions?

Composition of the Sample, Selection of the Respondents

For the study adults over 18 years of age were selected. Quota sampling method were used by public statistic data to determine the structure of the sample, however snowball sampling was also included as respondents could also distribute the questionnaires to those who belong to these the two investigated generations. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1 The Structure and Composition of The Sample |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Item | Percent |

| Gender | Male | 62 |

| Female | 38 | |

| Age | 18-24 | 53.9 |

| 25-39 | 46.1 | |

| Education | Elementary | 9 |

| Secondary | 57.4 | |

| Higher education | 33.6 | |

| LocationSettlement type | Capital | 35.9 |

| City | 17.7 | |

| Town | 30.2 | |

| Village, rural area | 16.2 | |

| Own research 2021, N=1364 | ||

In our investigations we directly concentrated on younger adults, especially two generations: Generation Z (18-24 years of age) and Generation Y, the Millennials (25-39 years of age). We delimited the generations by Oblinger & Oblinger (2005). According to them Gen-Y, Millennials were born between 1981-1995, Postmillennials, Generation Z were born after 1995. Concerning Generation Z, we only investigated members over 18 years of age, whom we can considered a young adult.

Results and Discussion

Several aspects of consumer consciousness were investigated, especially health, price, value, brand, society and environment consciousness were in focus basically concentrating on foods. In the case food choice several aspects can be investigated nevertheless age and food preference seems to be determining in this process (van Meer et al., 2016). However sustainable products are perceived as higher value and higher quality (Magistris & Gracia, 2016) not all of respondents keeps sustainability as priority in their head. According to table 2 Generation Z relate more excessively to this question than Generation Y. 20.2 % of Generation Z do not know or do not really care about sustainability and sustainable consumption, nevertheless almost half of them (49.8%) try to do something for sustainability, that is true for the Millennials as well.

| Table 2 Generation Differences in Assessment of The Importance of Sustainable Development |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is your opinion in connection of sustainable development? | Generation Z | Generation Y | Total | ||

| 18-24 | 25-34 | 35-39 | |||

| I do not know too much about it | % within What is your opinion in connection of sustainable development? | 60.80% | 19.30% | 19.90% | 100.00% |

| % within Age | 16.70% | 11.70% | 13.70% | 14.80% | |

| % of Total | 9.00% | 2.90% | 2.90% | 14.80% | |

| Adjusted Residual | 1.9 | -1.7 | -0.6 | ||

| I do not think I can do too much, so I do not really care about it | % within What is your opinion in connection of sustainable development? | 37.30% | 40.70% | 22.00% | 100.00% |

| % within Age | 3.50% | 8.50% | 5.20% | 5.10% | |

| % of Total | 1.90% | 2.10% | 1.10% | 5.10% | |

| Adjusted Residual | -2.6 | 3 | 0.1 | ||

| I do not think I would be able to do too much about it, however I try to do my best | % within What is your opinion in connection of sustainable development? | 57.80% | 23.10% | 19.00% | 100.00% |

| % within Age | 49.80% | 44.00% | 41.10% | 46.50% | |

| % of Total | 26.90% | 10.80% | 8.80% | 46.50% | |

| Adjusted Residual | 2.4 | -1 | -1.9 | ||

| I do everything | % within What is your opinion in connection of sustainable development? | 48.30% | 26.10% | 25.60% | 100.00% |

| % within Age | 30.00% | 35.80% | 39.90% | 33.60% | |

| % of Total | 16.20% | 8.80% | 8.60% | 33.60% | |

| Adjusted Residual | -2.8 | 0.9 | 2.4 | ||

| Own research 2021, N=1364, Skewness= -0.903, Kurtosis= -0.129 | |||||

Although there is a significance between generational belongingness and perceiving the importance of sustainable development, Cramer’s V value is low (0.098) meaning that the two fields are weekly associated. Hence attitude towards sustainability and sustainable consumption is not clearly predestinated by generational belongingness.

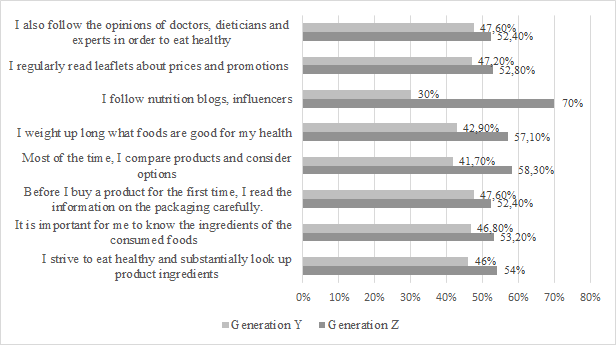

According to Gazdecki, et al., (2021) sustainable consumption can be propagated by providing information about environmental, economic and social consequences of excessive consumption. By Pilar (2021); Yekimov, et al., (2021) social media has a salient role in information seeking. However, people using social media for information seeking do alongside with others rather than replacing another. Younger people and women in general have a higher trust level in online channels (Kuttschreuter et al., 2014). We investigated how the respondents are seeking for information and what forms are the most defining ones for the different generations (Figure 1).

It can be seen that members of Generation Z seek for more information, 70% of the Z respondents follow influencers or blogs which is consistent with the findings of Pilar (2021); Yekimov, et al., (2021). At this point the main difference between the generations can be discovered as the Millennials significantly less devoted to bloggers or influencers (30%) they rather listen to real experts like doctors or dieticians (47.6%). The latter ones proved to be the most preferred information source together with the package labels. Importances of different factors in decision making were also investigated in case of foods reflecting to the various aspects of consciousness. Likert scales were used to measure these aspects. The value of Cronbach Alpha is 0.713 hence the consistency of the scale is acceptable nevertheless it also shows that presumably there are no redundant questions.

| Table 3 Importance of Different Factors Influencing Decision Making in The Case of Food Products |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||||||

| Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | ||||||

| Z | Y | Z | Y | Z | Y | Z | Y | Z | Y | |

| Reasonable price | 622 | 527 | 4.16 | 4.02 | 0.832 | 0.943 | -0.804 | -0.89 | 0.516 | 0.655 |

| Traditional, domestic food | 621 | 526 | 3.37 | 3.63 | 1.063 | 1.08 | -0.406 | -0.75 | -0.022 | 0.327 |

| Available at a discounted price | 622 | 526 | 3.87 | 3.86 | 0.913 | 1.011 | -0.586 | -0.968 | 0.188 | 0.721 |

| Conveniently available | 623 | 527 | 4.07 | 3.99 | 0.85 | 0.935 | -0.845 | -0.909 | 1.066 | 0.825 |

| Local food | 621 | 528 | 3.23 | 3.51 | 1.057 | 1.023 | -0.164 | -0.511 | 0.081 | 0.328 |

| Look fresh | 621 | 528 | 4.64 | 4.67 | 0.654 | 0.627 | -2.253 | -2.305 | 6.647 | 7.621 |

| Attractive packaging | 622 | 531 | 3.17 | 2.97 | 1.096 | 1.145 | -0.225 | -0.074 | -0.174 | -0.39 |

| External characteristics of food (size, colour, shape, shape) | 621 | 529 | 4.01 | 4.02 | 0.93 | 0.962 | -0.702 | -0.933 | 0.651 | 0.879 |

| Compliance with the requirements of a healthy diet (e.g. vitamin and mineral content, antioxidants) | 622 | 525 | 4.05 | 4.17 | 0.868 | 0.868 | -0.92 | -0.975 | 1.046 | 1.605 |

| Environmental protection during production | 621 | 527 | 3.8 | 3.83 | 0.987 | 1.015 | -0.517 | -0.631 | 0.518 | 0.508 |

| Consideration of animal welfare | 622 | 530 | 3.6 | 3.67 | 1.188 | 1.137 | -0.246 | -0.411 | -0.167 | 0.014 |

| GMO free | 621 | 527 | 3.81 | 4.02 | 1.143 | 1.056 | -0.55 | -0.695 | -0.047 | 0.343 |

| Branded product | 623 | 529 | 3.32 | 3.29 | 1.02 | 1.123 | -0.266 | -0.338 | 0.162 | -0.277 |

| Food fitting to special diets (e.g. paleo, vegan, etc.) | 622 | 529 | 2.86 | 3.06 | 1.366 | 1.424 | 0.214 | -0.024 | -0.848 | -1.007 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 612 | 515 | ||||||||

| Own research 2021, N=1364, 5 point Likert-scale (1=not important at all, 5=very important) | ||||||||||

According to the respondents the most influential factor during the decision making is the freshness of the food, which is true for both generations, also the external characteristic of the food is mostly important for them; however the role of packaging and even brands are not that decisive. Internal characteristics (GMO free, foods fitting to some special diet) does not prove to be as defining as the external ones especially for Generation Z. Members of the Generation Z are more price conscious (mean=4.16.), while the Millennials are more health conscious (mean=4.17). Convenient accessibility is also determining for both generations. Contrary to our assumptions social and environmental factors were somewhat important for the respondents, but not defining at all, however in general younger generations are presumably considered to be more sensitive to environmental and social problems and being more conscious in that question.

We also investigated the purchase and post-purchase behavior to get a clear picture whether the respondents are devoted to sustainable consumption in their attitudes or also in their behaviour.

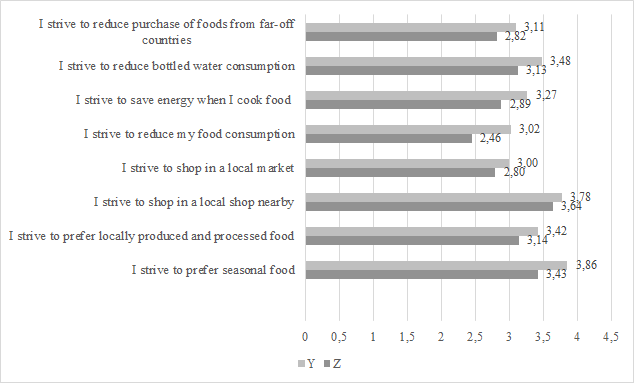

Previously it occurred that both generations try do for sustainability by their own statement. 80,1% of the respondents stated that they try to do their best or even they do everything to live in a more sustainable way. As Figure 2 shows striving for sustainable consumption can be discovered among both generations, however the level fluctuates depending on the action. In general it can be seen that Millennials tend to do in everyday action more for sustainable consumption than the members of Generation Y. Seasonal, local food preference and shopping nearby proved to be the most characteristic. Nevertheless, latter one can be also partially the result of the pandemic situation as people were prompted to shop nearby their homes. Among the possible purchase locations shops proved to be more preferred against local markets, however several markets do not operate on a daily basis and not offering just a limited range of food products. Respondents and especially members of Generation Z would do the less to restrain food consumption in general.

Conclusion

By our research results it can be seen that between the members of Generation Y and Generation Z, differences can be discovered in the level of their consciousness. In general, Millennials are more concerned and more conscious in environmental, sustainable, health and quality aspects, however Generation Z proved to be more price conscious. While by their own confession both generations are appreciably doing for sustainable consumer behavior, but at the same time their concrete actions prove to be moderately environmental conscious. At an ideal level environmental consciousness is important for them, at an action level this importance can be noticed moderately. Our results are partially contradicting to Molinillo, et al., (2020); Yamane & Kaneko (2021) that organic and sustainable food consumption would be salient, especially not because of ideological reasons. In generate we can state that among the respondent sustainability is important, but not a key driver in food consumption, especially not for Generation Z. These results also contradicting to Staniskis (2012) by whom younger generations already internalized the environmental threat and are ready for drastic changes in their consumption to save the planet. By our research results Generation Z tending to do the less in reduction and in general sustainability is not a key driver in food consumption.

There is a difference between the two generations in information seeking behaviour. Our results correspond with Pilar (2021); Yekimov et al., (2021) that Generation Z follow influencers, blogs and seek for more information. Millennials are less devoted to influencers they tend to listen to experts as doctors and dieticians. The latter ones proved to be the most preferred information source together with the package labels. Word-of-mouth communication, suggestions and recommendations are more credible than classical commercial messages to them.

References

- Bergh, J.V.D., & Behrer, M. (2016). How cool brands stay hot: Branding to generations Y and Z. London, TX: Kogan Page Publishers.

- Boardman, R., Parker-Strak, R., & Henninger, C.E. (2020). Fashion buying and merchandising: The fashion buyer in a digital society (1st Edition). New York, TX: Routledge.

- Carr, D.J., Gotlieb, M.R., Nam-Jin, L., & Shah, D.V. (2012). Examining overconsumption, competitive consumption, and conscious consumption from 1994 to 2004 disentangling cohort and period effects. The annals of the American academy of political and social science, 644(1), 220-233.

- Coderoni, S., & Perito, M.A. (2021). Approaches for reducing wastes in the agricultural sector. An analysis of Millennials’ willingness to buy food with upcycled ingredients. Waste Management, 126, 283-290.

- de-Magistris T., & Gracia, A. (2016). Consumers’ willingness-to-pay for sustainable food products: The case of organically and locally grown almonds in Spain. Journal of Cleaner Production, 118, 97-104.

- Dudás, K. (2011). A dimensions of conscious consumer behavior. Management Science, XLII, 7–8.

- Dudás, K. (2010). Conscious consumption.

- Ericson, C. (2019). Generational marketing for fitness professionals. American Fitness, 37(4), 22-25.

- Gazdecki, M., Gory´nska-Goldmann, E., Kiss, M., & Szakály, Z. (2021). Segmentation of food consumers based on their sustainable attitude. Energies, 14(11), 3179.

- Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (2000). Millennials rising: The next great generation. New York, TX: Vintage Books.

- Kuttschreuter, M., Rutsaert, P., Hilverda, F., Regan, Á., Barnett, J., & Verbeke, W. (2014). Seeking information about food-related risks: The contribution of social media. Food Quality and Preference, 37, 10-18.

- Lancaster, L.C., & Stillman, D. (2002). When generations collide: Who they are, why they clash, how to solve the generational puzzle at work. New York, TX: Collins Business.

- McCrindle, M., & Fell, A. (2020). Understanding generation alpha. Norwest, TX: McCrindle Research Pty Ltd.

- Micheletti, M. (2010). Political virtue and shopping: Individuals, consumerism, and collective action. New York, TX: Palgrave Macmillan ISBN: 9780230102705

- Molinillo, S., Vidal-Branco, M., & Japutra, A. (2020). Understanding the drivers of organic foods purchasing of millennials: Evidence from Brazil and Spain. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101926.

- Nicolau, J.L., Guix, M., Hernandez, G., Maskivker, M., & Molenkamp, N. (2020). Millennials’ willingness to pay for green restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102601.

- Oblinger, D.G., & Oblinger, J.L. (2005). Educating the next generation (1st edition). Washington DC, USA, TX: EDUCAUSE.

- Padveen, C. (2017). Marketing to millennials for dummies. Hoboken, TX: John Wiley & Sons.

- Pilar, L., Stanislavská, L.K., & Kvasnicka, R. (2021). Healthy food on the twitter social network: Vegan, Homemade, and Organic Food. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 3815.

- Pólya, É. (2017). Investigation of consumer consciousness in the case of foods in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County in Hungary. GRADUS, 4(2), 571-576.

- Rácz, G. (2013). The impact of changes in values and the trend of sustainable development on domestic food consumption. PhD Dissertation, Szent István University, Gödöll?.

- Reeves, T.C., & Oh, E.G. (2008). Generational differences, (3rd Edition). Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, 295-303.

- Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2019). Generation Z: A Century in the Making. New York, TX: Routledge. ISBN: 9781138337312

- Smith, J.W., & Clurman, A.S. (2010). Rocking the Ages: The Yankelovich report on generational marketing. New York, TX: HarperCollins.

- Sollohub, D. (2019). Millennials in architecture: Generations, disruption, and the legacy of a profession. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Spiegel, D.E. (2013). The Gen Y handbook: Applying relationship leadership to engage millennials. Jessup, TX: SelectBooks, Inc.

- Staniskis, J.K. (2012). Sustainable consumption and production: how to make it possible. Clean Technical Environmental Policy, 14, 1015-1022.

- Sujansky, J., & Ferri-Reed, J. (2009). Keeping the millennials: Why companies are losing billions in turnover to this generation- and what to do about it. Hoboken, TX: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN: 978-0-470-43851-0

- Tickell, J. (2018). The revolution generation: How millennials can save America and the world (before it's too late). New York, TX: Simon & Schuster. ISBN: 1501146092

- Tör?csik, M. (2003). Consumer behavior trends. Budapest, Hungary, TX: KJK-KERSZÖV Jogi és Verslo Kiadó Kft.

- Tör?csik, M. (2007). Customer behavior. Budapest, Hungary, TX: Akadémiai Kiadó Zrt.

- Tör?csik, M. (2011). Consumer behavior: Insight, trends, customers. Budapest, Hungary, TX: Akadémiai Kiadó Zrt.

- Van Meer, F., Charbonnier, L., & Smeets, P.A.M. (2016). Food decision-making: Effects of weight status and age. Current Diabetes Reports, 16, 84.

- Williams, K.C. & Page, R.A. (2011). Marketing to the generations. Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business, 3(1), 37–53.

- Willis, M.M., & Schor, J.B. (2012). Does changing a light bulb lead to changing the world? Political action and the conscious consumer. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 644(1), 160-190.

- Witt, G.L., & Baird, D.E. (2018). The Gen Z frequency: How brands tune in and build credibility. London, TX: Kogan Page Publishers.

- Wong, K. (2019). How to be a more conscious consumer, even if you’re on a budget. New York Times.

- Yamane, T., & Kaneko, S. (2021). Is the younger generation a driving force toward achieving the sustainable development goals? Journal of Cleaner Production, 292, 125932.

- Yekimov, S., Kucherenko, D., Bavykin, O., & Philippov, V. (2021). Using social media to boost sales of organic food. Earth and Environmental Science, 699(1), 012061.