Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

The Role of Emotional Intelligence on Services Marketing Capability

Jung-Yong Lee, Soongsil University

Kee-Sung Lee, Jeju National University

Chang-Hyun Jin, Kyonggi University

Keywords:

Emotional Intelligence, Organizational Culture, Service Marketing Strategy, Business Performance

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the components of emotional intelligence in service employees and also to analyze how emotional intelligence affects the development of a company’s services marketing capability. Organizational culture is selected as a moderating variable because it is considered a significant factor related to how service employees demonstrate emotional intelligence. The survey was administered in three major Chinese major cities—Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou—where many service companies are located, with employees hired from local populations (n=800). In our analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence in service employees and services marketing capabilities, emotional intelligence positively affected price development, product development, channel development, and communication development capabilities, the main components of services marketing capabilities. This in turn shapes emotional intelligence, which can play a substantial role in developing services marketing capabilities. In service employees, the use of emotion, as a component of emotional intelligence, consists of a sense of purpose, activity, and degree of effort backed by self-confidence. Emotional intelligence, when combined with enhanced use of emotion, can have significant effects on the components of services marketing capabilities, including price competitiveness, service product development, service channel development with suppliers and customers, service company and brand image establishment, and execution ability.

Introduction

As the service industry’s share of the global economy grows, interest in the industry is also increasing. Reflecting this trend, the Chinese government has approved and continued the expansion of Beijing’s service sector (State Council of Beijing, 2015). Because the roles of service employees have become more important, research on emotional intelligence in employees has been conducted more actively. Various economic indicators and economic forecasts indicate that the service industry claims a large share of the gross national product and employment in many countries around the world. The service industry has already had a substantial impact worldwide, while demand for services is constantly increasing. Given intensified competition between service companies, consumer desires have become economic indicators, and given the ever-accelerating pace of technology development, service companies must renew their offerings in the market to provide better value to customers through service innovation. As competition between service companies intensifies, what customers really want to purchase can be a core service. A core service is a service offering provided by a service company as a function of its core business as opposed, for example, to the service department of an automobile dealership whose core business is selling cars. This makes services marketing capabilities essential to the survival of a service company.

It is vital that an organization utilize members’ knowledge and manage their emotions (Higgs & Dulewicz, 1998; Druskat & Wolff, 2001; Palmer et al., 2002; Thomson, 1998). This is because the concept of emotional intelligence has emerged as a factor to consider in establishing a management strategy. As many researchers have reported, emotional intelligence in a company is directly related to business performance, so firms are incorporating emotional intelligence into their organizational management philosophies (Matthews et al., 2004). Emotional intelligence is considered a particularly important factor for service industry employees, because it includes key service characteristics—intangibility, inseparability, heterogeneity, and perishability. Thus, emotional intelligence in service employees may be closely related to a company’s services marketing capability. There have, however, been few studies examining the relationship between emotional intelligence in service employees and a company’s services marketing capability.

In this context, this study investigated the components of emotional intelligence in service employees and also analyzed how emotional intelligence affects the development of a company’s services marketing capability. Organizational culture is selected as a moderating variable because it is considered a significant factor related to how service employees demonstrate emotional intelligence. The results of this study may contribute to recognizing the importance of developing emotional intelligence in service employees to enhance the competitiveness of service companies, providing valuable guidelines for developing the marketing capability of such companies.

Theoretical And Empirical Background

Emotional Intelligence

Service industry employees meet customers directly, sell products, and manage stores. Their attitudes and behaviors can determine a company’s image, establishing the quality of and satisfaction with service that customers experience. One of the factors affecting the attitudes and behaviors of employees is emotional intelligence.

The concept of emotional intelligence was posited to help researchers understand how people manage unrefined and uncontrolled emotions (Goleman, 1995). Thorndike (1920) argued that emotional intelligence is based on social intelligence, an ability that is needed to act clearly in human relations. Wong & Law (2002) developed the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) model by simplifying existing complicated scales for measuring emotional intelligence, based on (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). The WLEIS model consists of four dimensions—self-emotional appraisal, others’ emotional appraisal, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion—constructed from 16 items.

Self-emotional appraisal indicates the ability to understand one’s own internal emotions and express them naturally. A person who has this ability can understand the causes of his or her own emotions and, for example, recognize happiness. Others’ emotional appraisal is the ability to recognize, observe, and understand other people’s emotions (Wong & Law, 2002). Use of emotion serves as a form of motivation with which people can meet challenges by using emotional information within personal memory (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Use of emotion indicates the ability to use one’s emotions to engage in constructive behaviors and obtain favorable or desired outcomes, and to achieve one’s goals by self-conviction and encouragement. Regulation of emotion is the ability to control one’s emotional impulses, to calm oneself, to control anger, and to be able to quickly recover from psychological distress (Wong & Law, 2002). In this study the authors applied the four sub factors of emotional intelligence as classified in previous studies.

Services Marketing Capability

The study attempted to understand the relationship between emotional intelligence and services marketing capability while focusing on the promotion and development of the marketing mix (also known as the “4Ps,” for price, product, promotion, and place) in support of services marketing capability. There have been few studies of the relationship between employee emotional intelligence and services marketing capability. The authors first connected the components of services marketing capability through the concept of service and the components of the marketing mix.

It is hard to find a consensus definition of “service,” because service differs from tangible or material goods that can be seen or touched and thus it is difficult to generalize as a process or output. The term “service” can contain varied various and heterogeneous components, and cannot be comprehensively classified as a single concept because the concept of service is continually being refreshed as society evolves. Blois (1974) said that service is an intangible product that includes conducting work, actions, and efforts that cannot be owned physically. Stanton (1984) identified service as independently distinguishable and an intangible form of actions to satisfy desires. Offering service and selling products do not necessarily have to be connected, and tangible goods do not necessarily have to be used in providing a service. Even if tangible goods have to be used, ownership of the associated service is not transferred. Service entails intangible activities without ownership that can be established to provide tangible goods. It can refer to all activities that are provided in selling a product. For our purposes we note four characteristics of service that differ from those involved in offering tangible products: intangibility, inseparability or simultaneity, heterogeneity, and perishability (Sasser et al., 1978).

The marketing mix ideally consists of an optimal combination of marketing means, chosen by managers through strategic decision-making at a certain point in time, based on environmental conditions, to achieve marketing objectives. It consists of the so-called 4Ps—product, price, place, and promotion—a concept according to which a commodity or service should be sold in accordance with the desires of consumers through analysis and a combination of factors (McCarthy & Perreault, 1987). Borden (1964) referred to the marketing mix as a set of marketing means and tools used to achieve marketing goals in a target market. According to (Waterschoot & Bulte, 1992), the marketing mix was first introduced by Neil Borden of the American Marketing Association (AMA) as a mix of factors designed to facilitate rapid responses to the market, and many marketing scholars have worked on refining the concept.

A capability is a company’s comparative competitiveness (Prahalad & Hamel, 1990). Based on this definition, a marketing capability is the relative competitiveness of a company. A specific definition of marketing capability was first established by (Day, 1994). He defined marketing capability as an integrated process that adds corporate service and commodity value and satisfies competitive demand to apply corporate collective skills, knowledge, and resources to market-friendly expectations. According to (Kohli et al., 1993), marketing capability is a company’s ability to generate customer value and achieve performance by using its knowledge and resources. A company with a stronger marketing capability than its competitors can understand customers’ needs and desires, comprehending the decision-making or purchasing behaviors of customers. Thus, a company with superior marketing capability is excellent at branding, product positioning, and selecting a target market. A company with distinct brands and products will show outstanding financial performance with high margins.

John, et al., (1999) divide a company’s functional capability into three categories: marketing, research and development, and operating capabilities. A company with stronger marketing capability than its competitors identifies the needs of consumers and understands factors affecting their choice behaviors more effectively. Marketing capabilities comprise a company’s ability to achieve favorable results using knowledge and resources to generate customer value. A company with stronger marketing capabilities than its competitors not only understands the needs and desires of customers but also comprehends consumer behaviors such as purchase selection and decision-making.

The marketing capabilities of service companies can be regarded as merely subordinate capabilities among their organizational abilities, and yet some researchers argue that the effects of such capabilities are sufficiently robust to improve corporate performance. According to (Pitt & Kannemeyer, 2000), corporate profitability and sales are intimately related to marketing and financial capabilities, and marketing capabilities play diverse, complicated roles in terms of functionality. Thus, firms must devote resources to developing and promoting marketing capabilities.

Business Performance

Business performance results from efficient and effective management of human and material resources. Timmons, et al., (1985) measured performance quantitatively by reference to profitability, sales, Return on Equity (ROE), employment growth rate, the sales-to-assets ratio, and the sales-to-employees ratio as indicators. Subjective or qualitative measures of achievement include external capital procurement capability, employee satisfaction, survival probability, and social contribution. The study measured the mean values of these factors empirically.

Business performance can also be defined by reference to perceptions of managerial performance (sales growth, comparison of sales with those of competitors, service satisfaction, etc.) (Reichel & Haber, 2005). When performance is measured on the basis of these definitions, financial performance, organizational capabilities, work engagement, and satisfaction are included. Business performance has been analyzed as a function of objective, subjective, financial, and non-financial performance (Stuart & Abietti, 1987). Many researchers suggest that multiple indicators of corporate performance should be used, such as employee growth rate, sales growth rate, sales, net profits, market share, and profitability, which could be used to measure Return on Assets (ROA), Return on Investment (ROI) and ROE to avoid errors caused by reliance on a single indicator (Murphy et al., 1993; Westhead et al., 2001). Venkatraman & Ramanujam (1986) suggested three performance indicators: subjective financial performance, business performance (market share, growth rate, diversification, and product innovation), and organizational effectiveness (satisfaction, quality of working life, and social power). Many researchers have used subjective assessments in measuring business performance (Narver & Slater, 1990; Kohli et al., 1993). The authors of this study measured the business performance of service companies by applying items used in non-financial methods.

Concept of Organizational Culture

The innovative capabilities of enterprisers and entrepreneurs can affect corporate performance. Several studies have established associations between managers’ social and psychological capital and corporate performance. In terms of organizational culture, previous studies have focused on the effects of social and psychological capital on organizational performance, human resources development, and the corporate decision-making process. Leana & Buren (1999) presented employment practices as the main process promoting or restraining social capital within an organization, suggesting that organizational performance is affected by the formation of organizational social capital (cooperativeness and trust) and by employment practices (stable relations, strong standards, and concrete roles). According to (Schein, 1984), an organization could solve problems of internal integration and environmental adaptation through discovery, invention, development, and learning. This is a pattern in the existing process, thought to be valid and effective, that teaches new employees having problems adapting to organizational life a way that they can feel and realize success.

According to Goffee & Jones (2000), organizational culture consists of widely shared symbols, behaviors, assumptions, and values, reflecting how business operations are handled within an organization. Martin (2002) argued that culture assumes various shapes within organizations and struggles between subcultures can arise. Athos & Pascale (1981); Peters & Waterman (1982) divided the components of organizational culture into shared values, strategy, structure, a management system, staff, management skills, and leadership style. The concept of organizational culture involves several factors such as beliefs, norms, customs, and values, and can vary according to research method and researchers’ perspectives.

Hypotheses and Theoretical Model

The purpose of this study was to investigate the components of emotional intelligence and to understand how emotional intelligence in service employees affects services marketing capabilities. Considering services marketing capabilities can be help us understand the influence of emotional intelligence on business performance and the moderating effects of organizational culture. To analyze these influence relationships and relationships involving moderating effects, the authors established a research model and hypotheses and used statistical techniques to test them. The hypotheses established in this study are as follows.

Emotional Intelligence and Services Marketing Capabilities

As psychology and business administration studies have focused recently on emotional intelligence, both attributes such as the rationality of organizational members and members’ emotions have received much interest (Goleman, 1999). Emotional intelligence significantly improves performance based on cognitive abilities related to general intelligence (Strickland, 2000; Lam & Kirby, 2002). A person who can empathize with others can accurately assess and express both their own and others’ emotions, controlling emotions to adapt to social life. Wong & Law (2002) argued that managers with well-developed emotional intelligence could use it to influence organizational engagement while emotional intelligence in mid- and upper-level managers affects the job satisfaction and performance of their subordinates.

Abraham (1999) emphasized the need for and roles of emotional intelligence in the workplace, classifying emotional intelligence as a combination of the ability to accurately assess and express their own or others’ emotions, the ability to appropriately control emotions, and the ability to use emotion-based knowledge to solve problems. These types of emotional intelligence are closely related to organizational engagement, organizational citizenship behaviors, and the cohesiveness of working groups in workplaces.

Based on existing studies, emotional intelligence in service employees can be closely related to service product development, price strategy, and channel and communication development capabilities, which are sub-elements of services marketing capabilities. Thus, the following hypotheses can be derived:

H1-1: Emotional intelligence will have positive effects on service product development capability as a component of services marketing capabilities.

H1-2: Emotional intelligence will have positive effects on service price development capability as a component of services marketing capabilities

H1-3: Emotional intelligence will have positive effects on service channel development capability as a component of services marketing capabilities.

H1-4: Emotional intelligence will have positive effects on service communication development capability as a component of services marketing capabilities.

Relationship between Services Marketing Capabilities and Business Performance

According to previous studies, the innovative capabilities of enterprisers and entrepreneurs can affect business performance. Moreover, the social and psychological capital of managers are associated with such performance (Jin, 2016, 2017). Business performance in service companies, as mentioned above, can be divided into financial and non-financial performance. In general, the business performance of service companies results from several factors.

Many researchers have used subjective assessments to measure business performance (Venkatraman & Ramanujam, 1986). There are various precedence factors in business performance, including market share, growth rate, product diversification and innovation, organizational effectiveness, employee satisfaction, the quality of working life, and social power.

Unlike manufacturers, for example, what service companies sell is characterized by intangibility, inseparability or simultaneity, heterogeneity, and perishability (Sasser et al., 1978). Service is intangible in essence and should be regarded as a set of actions that satisfy consumer desires. Thus, it may be natural for business performance in a service company to rely on the services marketing development capabilities of employees. This study focused on the services marketing capabilities of service employees because such capabilities can be related significantly to business performance. In this context, the following hypotheses can be established:

H2-1: The service product development capability will have positive effects on business performance.

H2-2: The service price development capability will have positive effects on business performance.

H2-3: The service channel development capability will have positive effects on business performance.

H2-4: The service communication development capability will have positive effects on business performance.

Moderating Effects of Organizational Culture

Insofar as organizational culture can be defined as a function of specific behaviors and practices in an organization (Gregory, 1983), organizational culture is contained within the language, ideology, consciousness, beliefs, symbols, and traditions of organizational members. It may change how organizational members interpret the importance of activities and issues within an organization. In addition, organizational culture refers to the knowledge system of organizational members (Sathe, 1983).

According to (Deal & Kennedy, 1982), every organization has an organizational culture encompassing its values, central characters, environments, customs, and rituals as informal guidelines that inform employees how to behave in various situations. Based on organizational culture, including ideology, customs, knowledge, skills, beliefs, values, and symbols shared by service company members, the relationships established through research hypotheses can differ. The conceptualization of organizational culture established as a moderating variable in this study is judged to serve as a moderator when the emotional intelligence of service employees affects services marketing capabilities. Thus, a final hypothesis can be proposed as follows:

H3: Organizational culture will have a moderating effect when emotional intelligence affects services marketing development (product (H3-1), price (H3-2), channel (H3-3), and communication (H3-4)) capabilities.

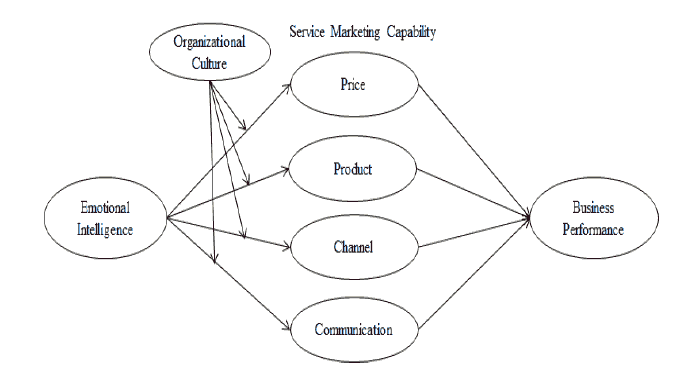

Theoretical Model

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between emotional intelligence in service employees and services marketing capabilities, to understand the relationship between services marketing capabilities and business performance, and to determine the extent to which organizational culture serves as a mediator in these relationships. The research hypotheses and research model draw on the theoretical background presented above. Figure 1 shows the research model for the purpose of this study.

Research Methodology

Survey Procedure

The authors of this study conducted a survey of Chinese service employees. According to the standard classification, the service industry was classified for the purposes of this research into the following business types: finance, insurance, accounting, law, advertising, corporate outsourcing, and others including retail, foodservice, accommodations, entertainment, culture, art, hospital, automobile service, hotels, and airlines.

The questionnaires began with demographic questions about gender, business type, position, years of employment, number of employees, and service types, followed by issues related to organizational culture consisting of emotional intelligence, services marketing capabilities, business performance, and moderating variables. Before administering the survey, the authors conducted a preliminary survey of 20 employees of service companies to gauge their understanding of questions, eliminate typos, and inform editing. Reliability and factor analyses were also performed.

To understand emotional intelligence in Chinese service employees, the survey was administered in three major Chinese cities—Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou—where many service companies are located, with employees hired from local populations. The questionnaires were sent to employees through visits, e-mails, and faxes. A total of 800 questionnaires were used for the analysis. The SPSS statistical package and a statistical program for structural equation modeling were used for statistical analysis.

Operational Definitions of Variables

Based on the literature review, we decomposed the emotional intelligence of service employees into the following factors: self-emotional appraisal, others’ emotional appraisal, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion. A total of 16 items (four for each factor) were used for measurement purposes (Gustafson, 2003; Mayer & Salovey, 1993; Strickland, 2000; Lam & Kirby, 2002; Wong & Law, 2002). In this study, emotional intelligence was defined as an individual’s capacity to understand others’ emotions based on an understanding of his or her own emotions and development and using emotions effectively based on self-regulation and control of his or her own emotions.

As noted, services marketing development capabilities consist of product development capability, price development capability, channel development capability, and communication development capability (McCarthy & Perreault, 1987). The items used in this study were revised from those used in previous research (Yarbrough et al., 2011). Twelve items comprise services marketing development capabilities: three to represent product development, three to represent price development, three to represent service channel development, and the remaining three to represent marketing communication development capability.

To measure business performance, we drew from items used in previous studies (Stuart & Abetti, 1987; Venkatraman & Ramanujam, 1986). We measured these component items using three questions pertaining to market share, productivity, and satisfaction based on enhanced brand recognition (Zarhra, 1996).

After establishing organizational culture as a moderating variable, we decomposed it into four organizational subcultures: rational, development, consensus, and hierarchy. We used 16 questions, which were revised based on questions used in existing studies. All question items were measured by 5-point Likert Scales.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The eventual sample consisted of 352 men and 448 women who filled out 800 questionnaires. Companies that had been operating for more than 10 years comprised 40% (n=320) of the sample, while 17% (n=216) of the companies had been operating for 5 or fewer years. Firms with more than 50 employees comprised 23% (n=184) of the sample companies, while 39% (n=312) of the companies had 10 employees or fewer (see Table 1).

| Table 1 Sample Characteristics |

||

|---|---|---|

| Index | n=800(%) | |

| Sex | Male | 352 (44) |

| Female | 448 (56) | |

| Size | 10 employees below | 312 (39) |

| 10–30 | 168 (21) | |

| 30–50 | 136 (17) | |

| 50 above | 184 (23) | |

| Service Industry | Accommodations | 118 (15) |

| Leisure & Entertainment | 89 (11) | |

| Personal Service | 106 (13) | |

| Health Service | 87 (11) | |

| Business | 86 (11) | |

| Education | 92 (12) | |

| Financial Service | 103 (13) | |

| Social–welfare | 93 (12) | |

| Others | 26 (.03) | |

| Working Years | 5 years below | 216 (27) |

| 5–10 | 264 (33) | |

| 10–20 | 216 (27) | |

| Over 20 years | 104 (13) | |

Convergent Validity and Discriminant Validity

This study tested the scales for dimensionality, reliability, and validity using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) before assessing the hypothesized relationships shown in Figure 1. Cronbach’s alpha exceeded the standard acceptance norm of 0.70 for all variables. Reliability was measured at 0.94 for sixteen items measuring emotional intelligence, 0.93 for twelve items measuring services marketing capability, 0.91 for four items measuring business performance, and 0.94 for sixteen items measuring organizational culture. The study first performed principal components factor analysis with varimax rotation on the initial items, employing a factor weight of 0.50 as the minimum cutoff value. As shown in Table 2, the factor loadings of the items in the measures range from 0.691 to 0.912, demonstrating convergent validity at the item level.

| Table 2 Results of Factor Analysis |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | ||||||

| Construct | Items | F.L | Construct | Items | F.L | ||

| Sep-01 | 0.823 | Price Capability | PRI1 | 0.796 | |||

| Self-Emotional | Sep-02 | 0.856 | PRI2 | 0.832 | |||

| Appraisal | Sep-03 | 0.693 | PRI3 | 0.774 | |||

| Sep-04 | 0.702 | Product Capability | PRO1 | 0.758 | |||

| Other ‘s Emotional | OEA1 | 0.75 | PRO2 | 0.732 | |||

| Appraisal | OEA2 | 0.789 | PRO3 | 0.754 | |||

| OEA3 | 0.697 | Marketing Channel | CHA1 | 0.739 | |||

| OEA4 | 0.704 | CHA2 | 0.691 | ||||

| Use of Emotion | UE1 | 0.79 | CHA3 | 0.768 | |||

| UE2 | 0.87 | Communication | COM1 | 0.693 | |||

| UE3 | 0.808 | COM2 | 0.773 | ||||

| UE4 | 0.813 | COM3 | 0.709 | ||||

| RE1 | 0.839 | Business Performance | PER1 | 0.703 | |||

| Regulation of | RE2 | 0.728 | PER2 | 0.826 | |||

| Emotion | RE3 | 0.853 | PER3 | 0.794 | |||

| RE4 | 0.843 | PER4 | 0.912 | ||||

| Factor | Eigenvalues | % of Variance | Factor | Eigenvalues | % of Variance | ||

| Factor 1 | 8.13 | 50.8 | Factor 1 | 8.92 | 55.8 | ||

| Factor 2 | 1.54 | 9.63 | Factor 2 | 1.29 | 8.06 | ||

| Factor 3 | 1.22 | 7.61 | Factor 3 | 0.944 | 5.9 | ||

| Factor 4 | 1 | 6,28 | Factor 4 | 0.825 | 5.16 | ||

| 74.3 % of total variance extracted | Factor 5 | 0.767 | 4.8 | ||||

| 79.7 % of total variance extracted | |||||||

| Moderating Variables | |||||||

| Consensual Culture | CC1 | 0.832 | DC1 | 0.787 | |||

| CC2 | 0.748 | Developmental Culture | DC2 | 0.89 | |||

| CC3 | 0.749 | DC3 | 0.785 | ||||

| CC4 | 0.791 | DC4 | 0.806 | ||||

| Rational Culture | RC1 | 0.85 | HC1 | 0.698 | |||

| RC2 | 0.878 | Hierarchical Culture | HC2 | 0.726 | |||

| RC3 | 0.862 | HC3 | 0.684 | ||||

| RC4 | 0.869 | HC4 | 0.697 | ||||

| Factor | Eigenvalues | % of Variance | |||||

| Factor 1 | 6.65 | 55.4 | |||||

| Factor 2 | 1.36 | 11.3 | |||||

| Factor 3 | 1.11 | 9.23 | |||||

| Factor 4 | 0.527 | 4.39 | |||||

| 80.4 % of total variance extracted | |||||||

Note: F.L: Factor Loadings

As shown in Table 3, discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the correlations of components with Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The final indicator of convergent validity is AVE, which measures the amount of variance captured by a construct in relation to the amount of variance that is attributable to measurement error. AVE also satisfies the standard of 0.5, which means that the measurement indexes exhibit convergent validity. AVE falls between 0.692 and 0.736, and the means of the squares of the correlation coefficients fall between 0.018 and 0.274, which indicates that AVE is higher than the means of the squares of the correlation coefficients (r²). This also satisfies the requirement of discriminant validity for research hypothesis model verification.

| Table 3 Discriminant Validity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Emotional Intelligence | 0.73 | 1 | |||

| ServicesMarketing Capability | 0.72 | 0.112** | 1 | ||

| Business Performance | 0.69 | 0.274** | 0.030** | 1 | |

| Organizational Culture | 0.74 | 0.135** | 0.018** | 0.119** | 1 |

Hypothesis Testing

Structural Equation Modeling

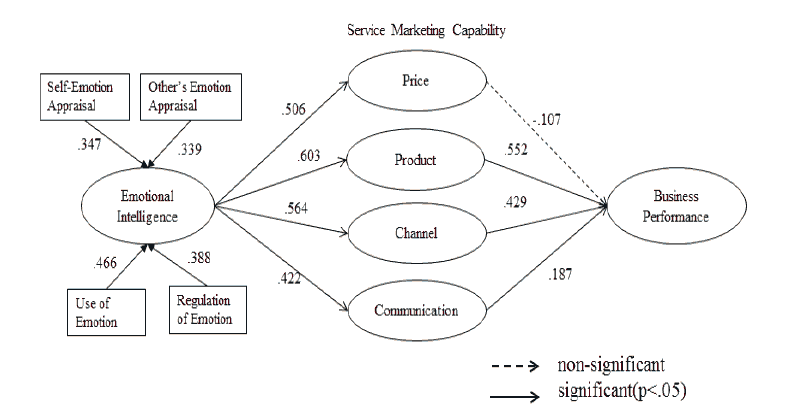

To test the structural relationships in the model, the hypothesized causal paths were estimated. Five hypotheses were supported and one was not supported. The results are shown in Table 4 and Figure 2, and they indicate that emotional intelligence has positive effects on price capability (path coefficients: γ=0.506, p<0.05), product capability (path coefficients: γ=0.603, p<0.05), channel capability (path coefficients: γ=0.564, p<0.05), and communication capability (path coefficients: γ=0.422, p<0.05). Thus, H1-1, 1-2, 1-3, and H1-4 were supported.

Product capability (path coefficients: γ=0.552, p<0.05), channel capability (path coefficients: γ=0.429, p<0.05), and communication capability (path coefficients: γ=0.187, p<0.05) have positive effects on business performance. However, price capability does not have positive effects on business performance (path coefficients: γ=-0.107, p>0.05). Thus H2-2, H2-3, and H2-4 were supported but H2-1 was not.

| Table 4 Results of Path Analysis |

||

|---|---|---|

| H | Paths | Coefficients |

| H1-1 | Emotional Intelligence → Price Capability | 0.506***(0.684)/z=10.647 |

| H1-2 | Emotional Intelligence → Product Capability | 0.603***(0.635)/z=9.943 |

| H1-3 | Emotional Intelligence → Channel Capability | 0.564**(0.631)/z=9.067 |

| H1-4 | Emotional Intelligence → Communication Capability | 0.422***(0.586)/z=8.871 |

| H2-1 | Price Capability → Business Performance | -0.107(-0.032)/z=0.063 |

| H2-2 | Product Capability → Business Performance | 0.552***(0.501)/z=9.412 |

| H2-3 | Channel Capability → Business Performance | 0.429***(0.633)/z=4.529 |

| H2-4 | Communication → Business Performance | 0.187***(0.326)/z=2.483 |

| Goodness of Fit: ?²=4583.2, df=423, p=0.000, CFI=0.943, GFI=0.882, AGFI=0.870, NFI=0.872, NNFI=0.925, SRMR=0.091, RMSEA=0.051 | ||

Moderating Effects

To test the moderating effects of organizational culture, multi-group CFA analysis with covariance structural analysis was conducted using EQS6b (Bentler, 1992) and MLE (the Maximum Likelihood Method). Multi-group analyses followed the steps suggested by (Byrne, 1994; Kline, 1998) by examining statistical differences across the two groups. The values of selected fit indexes for the multi-sample analysis of the path model with equality-constrained direct effects are reported in Table 5, which shows the standardized solutions. The tests show that interaction between emotional intelligence and price capability (χ²=0.502, p>0.05) was not significant, but only in cases in which the direction of the interaction was not completely opposite to the predicted effect, so the relationship was not supported. However, the tests show that interaction between emotional intelligence and product, channel, and communication capabilities (χ²=3.732, p<0.05 for product, χ²=5.324, p<0.05 for channel, and χ²=4.652, p<0.05 for communication) were significant, in the three cases in which the direction of interaction was completely opposite to the predicted effect, so the relationships were supported.

| Table 5 Results of Moderating Effects of Organizational Culture |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | Path | Path Coefficient | χ² Modification | |

| High | Low | |||

| H3-1 | Emotional Intelligence → Price Capability | 0.623 | 0.593 | χ²=0.509(p=.476) |

| H3-2 | Emotional Intelligence → Product Capability | 0.504 | 0.442 | χ²=3.734(p=.053*) |

| H3-3 | Emotional Intelligence → Channel Capability | 0.581 | 0.542 | χ²=6.213*** |

| H3-4 | Emotional Intelligence → Communication Capability | 0.613 | 0.483 | χ²=4.751*** |

Low: Classification based on Type of Organizational Culture (e.g., rational, development, consensus, and hierarchy cultures)

Conclusions and Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the relationships between emotional intelligence in service employees and services marketing capability and between services marketing capability and business performance. In our analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence in service employees and services marketing capabilities, emotional intelligence positively affected price development, product development, channel development, and communication development capabilities, the main components of services marketing capabilities. Although price development capability as a component of services marketing capabilities was expected to positively affect business performance, in our findings it did not do so. Meanwhile, product development, channel development, and communication development capabilities, as the other components of services marketing capabilities, positively affected business performance.

Regarding the moderating effects of organizational culture, emotional intelligence based on organizational culture made no difference in price development capability, while moderating the relationships between emotional intelligence and product development, channel development, and communication development capabilities ran in a positive direction.

Managerial Implications

Emotional intelligence in service employees was directly related to price, product, channel, and communication capabilities as components of services marketing capabilities. The components of emotional intelligence can be divided into four factors—self-emotional appraisal, others’ emotional appraisal, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion. We found that others’ emotional appraisal, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion were shown to be more deeply associated with the formation of emotional intelligence in service employees than self-emotional appraisal. Emotional intelligence was also found to affect services marketing capabilities, and emotional intelligence in service employees seemed to serve as a significant indicator for the development of services marketing capabilities. Among the four components of emotional intelligence, self-emotional appraisal, which involves one’s own happiness, was less significantly recognized by the study participants than other components.

The study found that emotional intelligence had positive effects on services marketing capabilities (price, product, channel, and communication). The abilities of service employees to understand others’ emotions, to observe and be in communion with others’ emotions, and to understand emotions based on others’ behaviors can serve as significant factors in improving services marketing capabilities. In addition, it is important for service employees to control and regulate their emotions if they are to resolve situations rationally. This in turn shapes emotional intelligence, which can play a substantial role in developing services marketing capabilities. In service employees, the use of emotion, as a component of emotional intelligence, consists of a sense of purpose, activity, and degree of effort backed by self-confidence. Emotional intelligence, when combined with enhanced use of emotion, can have significant effects on the components of services marketing capabilities, including price competitiveness, service product development, service channel development with suppliers and customers, Service Company and brand image establishment, and execution ability.

Product development capability was found to have an insignificant effect on business performance. Product development capability involves coping with market change and price diversification, which may not be recognized as an influence on business performance. However, the sustainability and extent of service product development can be significant when judging business performance. The formation and maintenance of service channels and communication methods for enhancing brand image can be considered more important in assessing business performance as recognized by service employees.

Organizational culture was found to play a moderating role when emotional intelligence affected services marketing capabilities and business performance. This study recognizes four types of organizational culture: rational, development, consensus, and hierarchy. Emotional intelligence in service employees affected services marketing capabilities to a greater extent in an organizational culture in which service productivity, efficiency, and goal-setting were considered important and creativity and innovation were emphasized, than in an organizational culture in which affinity and participation were induced, the publicity of decision-making was secure, and mutual cooperation and trust were high as well as in an organizational culture in which rules and codes of conduct were intensified and processes of approval were consistent.

Under such organizational cultures, however, emotional intelligence in service employees had little effect on price development capability as a component of services marketing capabilities. Price is essentially financial, while emotional intelligence in service employees is intangible. Because service product development, channel formation and maintenance, and communication methods involve the development of ideas based on emotional intelligence, emotional intelligence can be more closely related to intangible asset formation in a service company. Services marketing capabilities can affect business performance more robustly when a service company’s organizational culture is more reasonable, emphasizes creativity, innovation, and cooperation in employees, and constructs a hierarchical order.

Based on this study’s path analysis, we also found indications related to sub-factors of emotional intelligence that explain, to a great extent, how to relate emotional intelligence in employees to the development of a firm’s services marketing capability. Thus, we encourage services marketing researchers who are interested in advancing the emotional intelligence literature to further pursue the topic of enhancing services marketing strategies. Self-emotional appraisal involves one’s own happiness but was recognized by the study participants to a lesser extent than other components. Employees’ emotional intelligence affects services marketing capabilities positively in a hotel business. Therefore, it would appear that employees who exhibit higher levels of self-emotional appraisal and other’s emotional appraisal and are better able to control and utilize their emotions can bring about higher service performance.

With respect to the results of the study, we have confirmed that emotional intelligence in employees can play a substantial role in developing a service firm’s services marketing capabilities. Emotional intelligence is closely related to key components of services marketing capabilities when combined with enhanced use of emotion. The results of this research imply that employees in service firms with superior emotional intelligence can be more productive because these firms depend so highly on human resources. A high level of services marketing development will bring about better outcomes in several service businesses because good service can generate customer repurchase and word-of-mouth effects. More generally, employees with superior emotional intelligence can support the development of services marketing capabilities in the service sector. The results of this study not only contribute to better understanding of the relationship between personal employee traits and job performance but also help to explain consumer behaviors such as purchase selection and decision-making.

Recommendations for Future Research

It might be inappropriate to generalize the results of this study because it targeted culturally similar subjects in a single country. While this study compared the organizational cultures of service companies in one country, additional studies are needed to compare service companies in multiple nations and cultural areas. Regarding the research analyses, this study did not execute the most accurate financial comparisons in measuring business performance in the companies under study. Although we developed a sophisticated approach to studying emotional intelligence in service employees, we could not consider accurate financial data because most of the companies in the sample depend on external agencies to manage their finances and accounting. Further studies are needed to analyze and compare business performance on a standard financial basis with more accurate information.

In this study, business performance was the final dependent variable, and yet it might be necessary to investigate the relationship between performance and services marketing capabilities by considering a company’s customer orientation and its employees’ job satisfaction as well as related individual employee variables. This study was also limited insofar as it did not consider any variables other than emotional intelligence as factors affecting services marketing capabilities. Further studies are needed to construct several variables to improve the explanatory power of the research model. Differences verification of the relationships in consideration of demographic variables might be also significant.

References

- Abraham, R. (1999), “Emotional intelligence in organizations: A conceptualization”. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs”, 125(2), 209-224.

- Athos, A.G., & Pascale, R.T. (1981). The art of Japanese management: Applications for American executives. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Bentler, P.M. (1992). EQS: Structural equation program manual. Los Angeles: BMDP Statistical Software.

- Byrne, B.M. (1994). Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic concepts, application, and programming.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Borden, N.H. (1964). “The concept of the marketing mix”. Journal of Advertising Research, 4(2), 2-7.

- Deal, T.E., & Kennedy, A.A. (1982). Corporate cultures: The rite and rituals of corporate life, reading. MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Druskat, V.U., & Wolff, S.B. (2001). Group emotional competence and its influence on group effectiveness. In Cherniss, C., & Goleman, D., (Editions), Emotional competence in organizations, 132-155, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

- Goffee, R., & Jones, G. (2000). “Why should anyone be led by you?” Harvard Business Review, 5, 63-70.

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

- Gregory, K.L. (1983). “Native-view paradigms: Multiple cultures and culture conflicts in organizations”. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, 359-376.

- Gustafson, B. (2003). “Are you meeting customers’ emotional needs?” Healthcare Financial Management, 57(4), 44-48.

- Higgs, M., & Dulewicz, V. (1998), “Top team processes: Does 6+ 2=10?”. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 13(2), 47-62.

- John, G., Weiss, A.M., & Dutta, S. (1999). “Marketing in technology-intensive markets: Toward a conceptual framework”. Journal of Marketing, 63(special issue), 78-91.

- Kline, R.B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications, New York.

- Kohli, A., Jaworski, B., & Kumar, A. (1993), “MARKOR: A measure of market orientation”. Journal of Marketing Research, 30(4), 467-477.

- Lam, L.T., & Kirby, S.L. (2002). “Is emotional intelligence an advantage? An exploration of the impact of emotional and general intelligence on individual performance”. Journal of social Psychology, 142(1), 133-143.

- Leana, C.R., & Buren, V.H.J. (1999). “Organizational social capital and employment practices”. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 538-555.

- Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R.D. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Science and Myth. Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

- Mayer, J.D., & Salovery, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In Salovey, P., & Sluyter, D.J., (Editions), Emotional development and emotional intelligence, New York: Basic Books, pp. 3-31.

- McCarthy, E.J. (1971). Basic marketing: A managerial approach, (3rd edition). Homewood, Illinois, USA.

- McCarthy, E.J., & Perreault, W.D. (1987). Basic marketing, (9th edition). Home wood, IL: Irwin.

- Murphy, K.M., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R.W. (1993), “Why is rent seeking so costly to growth?” American Economic Review, 83(2), 409-414.

- Narver, J.C., & Slater, S.F. (1990). “The effect of market orientation on business profitability”. Journal of Marketing, 54(5), 20-35.

- Palmer, B.R., Donaldson, C., & Stough, C. (2002). “Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction”. Personality and Individual Differences, l(33), 1091-1100.

- Peters, T.J., & Waterman, R.H. (1982). In search of excellence: Lessons from America's best-run companies. NY: Harper & Row.

- Prahalad, C.K., & Hamel, G. (1990). “The core competition of the corporation”. Harvard Business Review, 68(3), 79-91.

- Reichel, A., & Haber, S. (2005). “A three-sector comparison of small tourism enterprises performance: An exploratory study”. Tourism Management, 26(1), 681-690.

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. (1990). “Emotional intelligence”. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185-211.

- Sasser,W.E., Olsen, R.P., & Wyckoff, D. (1978). Management of service operations: Text and cases and readings. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, pp. 15-18.

- Sathe, V. (1985). Culture and related corporate realities. Homwood. IL: Richard D, Irwin.

- Strickland, D. (2000). “Emotional intelligence: The most potent factor in the success equation”. Journal of Nursing Administration, 30(3), 112-127.

- Stuart, R.W., & Abetti, P.A. (1987). “Start-up venture: Toward the prediction of initial success”. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(3), 215-230.

- Thomson, K. (1998). Emotional capital, capstone. Oxford.UK.

- Thorndike, E.L. (1920). “Intelligence and its uses”. Harpers Magazine, 140, 227-235.

- Timmons, J.A., Smollen, L.E., & Dingee, A.L.M. (1985). Venture Creation, (2nd edition). Hoomwood, IL: Richard D. Irwin.

- Van Waterschoot, W., & Bulte, C. (1992). “The 4P classification of the marketing mix revisited”. Journal of Marketing, 56(4), 83-93.

- Venkatraman, N., & Ramanujam, V. (1986). “Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches”. Academy of Management Review, 1(4), 801-808.

- Westhead, P., Cowling, M., & Howorth, C. (2001). “The development of family companies: Management and ownership imperatives”. Family Business Review, 14(4), 369-385.

- Wong, C., & Law, K.S. (2002). “The effect of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study”. Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 243-274.

- Yarbrough, L., Morgan, N.A., & Vorhies, D.W. (2011). “The impact of product market strategy-organizational culture fit on business performance”. Journal of the Academy Marketing Science, 39, 555-573.

- Zahra, S.A. (1996). “Goverance, ownership, and corporate entrepreneurship: The moderating impact of industry technological opportunities”. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1713-1735.