Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 4S

The underlying mechanisms linking ethical leadership to employees??? ethical behaviours

Kien The Mai, International University

Uyen Nu Hoang Ton, International University

Hoa Doan Xuan Trieu, International University

Phuong Van Nguyen, International University

Citation Information: Mai, K.T., Ton, U., Trieu, H., & Nguyen, P.V. (2022). The underlying mechanisms linking ethical leadership to employees’ ethical behaviors. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(S4), 1-17.

Abstract

Employees' unethical behavior has remained a relatively concerning problem regarding ethics and organizational effectiveness. Given its detrimental effects and high frequencies in developing countries, studies on this problem would serve as a fundamental empirical document that clarifies the dynamics around employee's integrity and further implies solutions for future ethical management. The current research investigates the mechanism linking ethical leadership to employees' ethical behaviors with the inclusion of coworker ethical behavior, perceived organizational politics, and organizational commitment. The target respondents comprise employees working in joint-stock companies in Ho Chi Minh City of Vietnam. The study utilizes PLS-SEM approach to analyze the sample of 263 valid observations to test the research model. The current research revealed significant effects of ethical leadership on enhancing employees' ethical conducts, widely shared morality by their coworkers, individual's emotional attachment to the organization as well as creating a more ethical working climate where the perception of organizational politics is minimized. Employees are therefore encouraged to behave ethically in accordance with others' supportive actions and the organizational bonds developed out of leaders' genuine care for subordinates' well-being and advancement. From the findings, the study sheds light on a comprehensive understanding of the positive correlation between ethical leadership and employees' ethical conducts as well as cruciality of ethical trainings and selection for managers, transparent organizational regulations, convenient methods for open discussion, honest report, and sufficient support for employees' development.

Keywords

Ethical Leadership, Employees' Ethical Behavior, Coworker Ethical Behavior, Organizational Commitment, Perceived Organizational Politics, Joint-Stock Companies

Introduction

Living in the Information Age, people are inspired to be socially active and take ethical standards into their decisions. This, in turn, progressively alters the notion of a successful organization (Waddock, Meszoely, Waddell & Dentoni, 2015). Companies are put under immense pressure not only to possess better production, adapt to simultaneous change and competition but also to operate their business ethically, delivering greater sustainability and contributing to societies (Al Halbusi, Williams, Ramayah, Aldieri & Vinci, 2020; Nguyen, Trieu, Ton, Dinh & Tran, 2021; Thomas, 2014).

Nevertheless, this is only the tip of the iceberg, as ethical matters can deeply root in daily business activities. Specifically, it has been found that employees may behave unethically in the pursuit of fulfilling their self-interest objectives and personal advantages (Batabyal & Bhal, 2018; Brown & Treviño, 2014; Mayer et al., 2014; Rana & Sharma, 2016). These unethical behaviours are mainly conducted at the expense of the organization's internal and external stakeholders, causing decreased benefits for the greater group of people. Like other emerging countries, Vietnam's inefficiency of ethical management has let employees' misconduct remain an unresolved issue. As whether employees act ethically or not can have significant impacts on organizations, exploration of factors and correlations related to their behaviours should shed light on the enhancement of firms’ performance management and societal well-being.

Former studies showed that ethical leadership was a fundamental antecedent of positive organizational outcomes, influencing employees' ethical and unethical behaviors by explicitly setting normative behaviors at work (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Ko, Ma, Bartnik, Haney & Kang, 2018; Mitchell, Reynolds & Treviño, 2017; Wiernik & Ones, 2018). Although several studies confirmed the effect of ethical leadership on decreasing workers' tendency of committing workplace misconducts and unethical behaviors (Avey, Palanski, & Walumbwa, 2011; Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes & Salvador, 2009; Mayer, Kuenzi & Greenbaum, 2010; Stouten et al., 2010), there is lack of solid evidence showing whether employees' ethical behaviors can be necessarily increased with this style of leadership.

Furthermore, the organizational climate that employees work in is discovered to have prominent effect on their ethical behaviors (Al Halbusi & Hamid, 2018; Treviño, Den Nieuwenboer & Kish-Gephart, 2014). It should be noted that organizational climate is highly correlated with attributes of the leader as leaders significantly define the culture and ethics that shape the environment (Aryati, Sudiro, Hadiwidjaja & Noermijati, 2018). Nevertheless, there has been a scarcity of research on how ethical leaders can influence subordinates' ethical behaviors through the organizational climate, specifically perceived organizational politics. There is also a limited investigation on how this political condition can impact employees' behaviors.

Given the literature gaps above, it is critical that we initiate this innovative study that incorporates perceived organization politics in the conceptual model to clarify the dynamics between ethical leadership style and employees' ethical behaviors. We further include organizational commitment and coworker's ethical behavior to obtain comprehensive perspectives on mechanism affecting ethical conducts, ranging from the workers' internal self to possible external influences from colleagues and the surrounding working environment.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

Social Learning Theory

According to Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1986), individuals learn to behave appropriately by observing and imitating the norms in the social context. The theory suggests that leaders are perceived as credible role models as they demonstrate high levels of integrity and value-driven behaviors (Brown, Treviño & Harrison, 2005). Employees, in turn, pay close attention to these role models and adopt desirable behaviors that they have observed (Brown & Treviño, 2006).

Social Exchange Theory

According to Social Exchange Theory expressed by Blau (Blau, 1964), the social exchange between two parties in a relationship is rationalized based on two criteria, economic exchange (also known as transactional) and interpersonal behavior exchange (also called socioemotional) (Aryati et al., 2018). When individuals perceive benefits as transactional or socioemotional from others, they tend to feel the obligation to reciprocate by giving back. In other words, when leaders, colleagues, organizational procedures, and climate exhibit favorable behaviors or concern for the employees' well-being, employees would perceive those relationships to have high levels of trust and fairness. As a result, they value and maintain these relationships by committing themselves to act ethically and displaying beneficial behaviors to these people and their organizations in return (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Mayer et al., 2009).

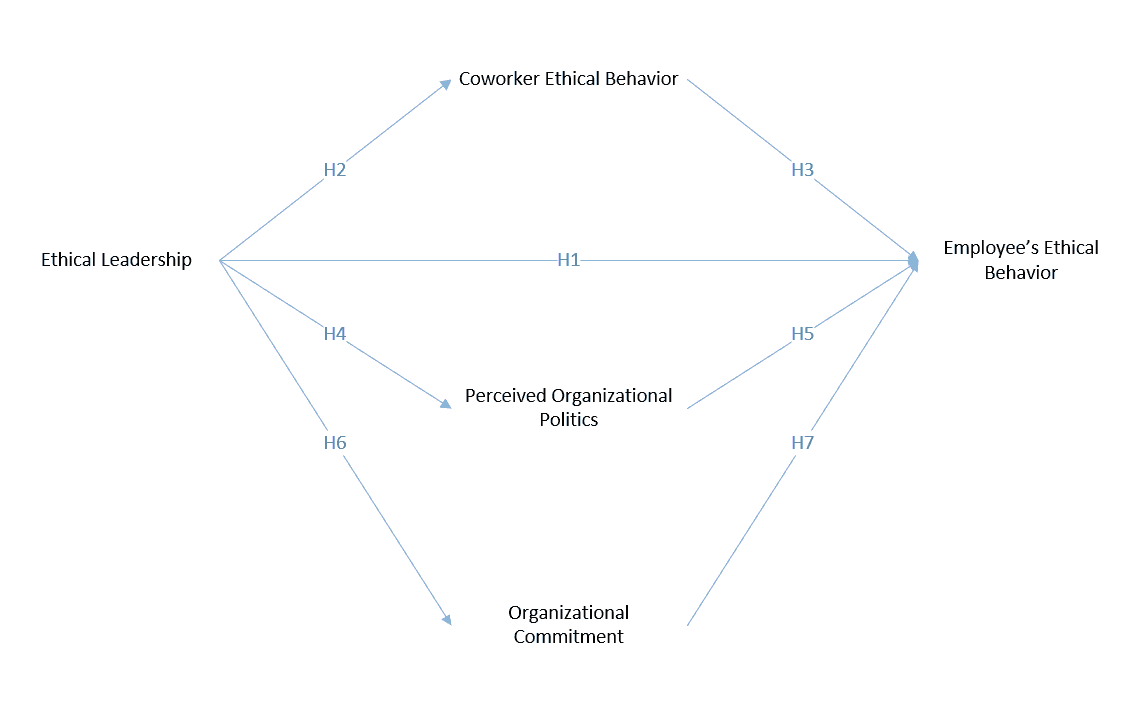

Hypothesis Development

Ethical Leadership

Ethical leadership relates to how a leader conducts themselves in their activities, interacts with other workers, and communicates important norms and values to subordinates via communication, decision-making, and reinforcement (Brown et al., 2005). It is stated that there are two critical aspects related to this form of leadership, which are moral personal factor and moral manager factor. The moral person component relates to the leader's virtuous qualities, such as honesty, trustworthiness, fairness, justice, and care for others. The moral manager component refers to the leader's actions and attempts to promote subordinates' ethical behavior, primarily via role modeling, incentives, punishment, or disclosure of ethical norms (Lin, Liu, Chiu, Chen & Lin, 2019).

Previous studies have suggested ethical leadership's inherent association with positive workplace outcomes. Leaders with ethical manners were discovered to positively affect followers' motivational processes in which employees are more willingly to give extra effort in their work (Yidong & Xinxin, 2013). Ethical leadership is also found to be significantly related to various dimensions of leadership effectiveness, boosting the employee's job satisfaction, performance, promotability evaluations and commitment (Kacmar, Andrews, Harris & Tepper, 2013; Letwin et al., 2016; Mo & Shi, 2018; Ofori, 2009). Notably, ethical leadership can increase probability of ethical problems reporting or whistle blowing as it gives subordinates a sense of interactional justice and creates the perception of an ethical working climate (Brown et al., 2005; Neubert, Carlson, Kacmar, Roberts & Chonko, 2009).

Employee's Ethical Behavior

Ethical behaviors are those that are deemed proper, lawful, and moral, and that individuals should follow based on agreed-upon principles and norms (Arnold, Beauchamp & Bowie, 2019). According to previous study by Pio and Lengkong (Pio & Lengkong, 2020), six key factors that affect ethical behavior in business are: individual's personal value, coworkers' behaviors, the influence from leaders and managers, financial position, ethics-related policies of the organization, and ethical practices of the industry which the individual is working in.

Being the representative of an organization, a leader is supposed to significantly induce individuals' behaviors within the firm (Burns, 1998). Leaders are also stated to have the ability to transform the workforce's moral concept and behaviors by giving practical and moral guidance to followers (Babalola, Stouten, Camps & Euwema, 2019; Karim & Nadeem, 2019; Neves, Almeida & Velez, 2018). Hence, ethical managers who demonstrate positive personal values, regulated conduct with active management can inspire ethical attitudes and conducts among employees (Al Halbusi, Williams, Mansoor, Hassan & Hamid, 2020).

The link between ethical leaders and employees is further explained by Social learning theory and Social exchange theory. Drawing from Social learning theory, employees tend to emulate the norms they observe in the workplace, especially from higher authority (Bandura, 1986). In line with the aspect of the moral person in ethical leadership, leaders are regarded as the role models that demonstrate appropriate behaviors and moral values (Gan, 2018). Consequently, followers are influenced to engage in identical ethical behaviors, making their values and attitude consistent with the role models. Resick et al. (Resick et al., 2011) also noted that the more similar the leaders' ethical conducts are to the common ethical traits in that particular culture, such as being accountable, honest, and respectful of others, the more likely employees would follow.

Additionally, Social exchange theory hints individuals' tendency to reciprocate the benefits that they receive from the others (Blau, 1964). By showing sincere consideration for the employees' well-being and benefits, leaders have created a socio emotional exchange with their followers (Mayer et al., 2009). Perceiving high levels of trust and fairness from higher authority and organizational practices, employees will be more convinced to behave in favor of their leaders and organization. In order words, they are more willing to behave ethically in return (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Brown et al., 2005; Kalshoven, Hartog & de Hoogh, 2013). Therefore, from the discussion above, we propose:

H1: Ethical leadership has positive influence on employee's ethical behavior.

Ethical Leadership, Employee's Ethical Behavior and Coworker's Ethical Behavior

On the basis of Social Learning and Social Exchange theories, employees' coworkers are identically directed towards integrous and moral conducts as they share similar experience under superior's ethical leadership. Among the company's workforce, colleagues are induced to follow ethical guidelines, role models as well as reciprocate when acknowledging beneficial social exchange in the workplace (Al Halbusi et al., 2020).

The aforementioned theories also suggest coworkers as additional vital learning sources for appropriate acts. In accordance with Social Learning perspectives, social contexts mold individuals’ behaviors with moral standards demonstrated by the collective group (Bandura, 1986; Barrick, Mount & Li, 2013). Coworkers, being an approachable embodiment of eligibility, offer situational cues on desirable traits and expected behaviors at work (Robinson, Wang & Kiewitz, 2014). They can influence individuals either through direct interaction or indirect established social norm (Kim, Kim, Han, Jackson & Ployhart, 2017). As individuals face uncertainty in determining whether to behave ethically, colleagues act as contextual signs for employees to imitate as well as ancillary encouragement towards ethical choices (O’Fallon & Butterfield, 2012). Additionally, in line with Social Exchange perspectives, workers may emulate others’ behaviors and make ethical decisions out of desire to establish social compatibility and strengthen mutual relationships with others (Afsar & Umrani, 2020; Blau, 1964). For instance, observation of economical consumption of company’s resources (such as electricity, commuting services or office supplies) among other workers would guide individuals to behave economical accordingly. Although some of ethical behaviors may not necessarily result in serious sanctions if individuals do not comply (such as turning off lights and equipment when not using), application of these ethical conducts help them to fit in the organizational culture and norms. Hence, as coworkers place social guidance toward ethical selections, employees would attempt to align themselves with observed preferences and values by displaying frequent ethical behaviors. From the discussion above, we propose the following:

H2: Ethical leadership has positive influence on coworker’s ethical behavior.

H3: Coworker’s ethical behavior has positive influence on employee’s ethical behavior.

Ethical Leadership, Employee’s Ethical Behavior and Perceived Organizational Politics

Organizational politics depicts deliberate use of tactics and powers that can enhance individual’s or group’s obtainment of self-interested benefits and advantages (Başar, Sığrı & Basım, 2018). Such conducts can take place in various organizational internal processes (such as promotion, decision-making, performance valuation) with myriad forms to execute, for example degrading and blaming others, getting close with superiors and influential individuals, creating allies, and giving compliments and praises for impression management. In this regard, Perceived Organizational Politics (POP) refers to the employees’ subjective assessment of how political and illegitimate their working environment is (Bergeron & Thompson, 2020). As one’s perception of an issue gives better guidance on reactions rather than the reality itself, it would be more relevant to investigate employees’ behaviors on the basis of their perspectives (Cheng, Bai & Yang, 2019).

Interpretation of organizational politics are vastly negative due to the self-serving and manipulative characteristics, which are usually at the expense of others and even the firm (Rosen, Ferris, Brown, Chen & Yan, 2014). Although political activities can offer benefits for those who exercise, they are generally referred as unethical and immoral as these behaviors direct people towards inequality and injustice in decision making and managerial practices (Başar et al., 2018). Besides frustration and damaged exchange relationship between employees and the organization, high levels of POP may increase inefficient working performances since individuals are now encouraged to participate in the political games instead of concentrating on their actual work value to earn rewards and recognition (Batabyal & Bhal, 2018; Vigoda-Gadot, 2007). In other cases, when employees do not have the capability to join the game or deal with perceived politics, the situation may impose threats to their well-being and working position, which will lead to lower productivity, higher stress and ultimately, job resignations. The results of study by Asrar-ul-Haq et al. (Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019) provide support for this rationale as they demonstrate the significant correlations between POP and subordinates’ work stress and turnover intentions.

An environment with ambiguous and unclear decisional guidelines would make room for ethical dilemmas and political execution (Gotsis & Kortezi, 2010). High levels of politics are also common in high power distance countries where employees are reported to experience low degrees of organizational fairness and immensely rely on their bosses for career advancement and salary increase (Lau, Tong, Lien, Hsu & Chong, 2017). Despite highlights on collectivism and harmonious relationships among members, benefits and rewards may be favorable distributed to certain groups or individuals at the cost of others in these nations (Kennedy, 2002).

Leaders may pose certain influences on the organizational climate shaped under their attributes and guidelines (Aryati et al., 2018). As leader significantly represents entity’s image, ethical leaders who are highly associated with transparency, honesty and justice allow subordinates to learn about the firm’s preferences for integrity, rather than political competition. Such realization helps to decrease levels of POP among workers (Cheng et al., 2019). On the other hand, when managers demonstrate lower frequency of moral choices and act opportunistically, employees are persuaded to believe in organization’s political tendency and, certainly, higher levels of POP.

In addition, ethical leadership can actively diminish the necessity to join political games in the workplace. Since employees’ performance, rewards and promotion are merely evaluated based on fair standards and the work contributed itself, there would be no need for subordinates to exercise political tactics so they can gain certain priority and biased benefits from superiors. Ultimately, ethical leaders outspread emphasis on employees’ work performance and value delivered, while giving the indication that self-serving activities are not welcome in this firm. Former studies by Kacmar et al. (Kacmar et al., 2013) and Kacmar et al. (Kacmar, Bachrach, Harris & Zivnuska, 2011) affirmed these ideas as they discovered significantly negative impacts of ethical leadership on POP. In other words, ethical leaders can create a far more equal and transparent working climate that employees would associate it with lower levels of organizational politics. Therefore, being consistent with previous research, the current study puts forward:

H4: Ethical leadership negative influence on POP.

Different social contexts were identified to generate different individuals’ engagement in ethical behaviors (Caruso & Gino, 2011; Gino, Schweitzer, Mead & Ariely, 2011; Kish-Gephart, Harrison & Treviño, 2010; Lau et al., 2017). A reliable and collegial climate as well as merit-based pay increase promotes workers’ manners to support others and organization’s well-being, including offering advice and feedbacks, or helping and praising ethical contributions (Paillé, Grima & Dufour, 2015). In contrast, strongly political culture presses these encouragements. Since subordinates’ advantages and benefits are highly linked to their relationships with certain political parties, individuals would lose trust in fair organizational rewards while not being motivated for ethical intentions and solutions (Cheng et al., 2019).

The correlation between POP and employees’ ethical behaviors can further be examined from the perspective of Social Exchange theory. Favoritism and sense of adversity in political settings would lead to feelings of unfairness, exhaustion and organizational unconcern for their well-being (Huang, Chuang & Lin, 2003; Karatepe, Babakus & Yavas, 2012; Rosen, Levy & Hall, 2006). Hence, application of political tactics obstructs expected mutual beneficial exchange between employees and the firm, leaving less incentives for individuals to reciprocate and display ethical behaviors that can benefit others. Contrarily, transparent working climate with hardly any political practices stimulates tendency for ethical conducts. From these reasonings, we infer:

H5: POP has negative influence on employee’s ethical behavior.

Ethical Leadership, Employee’s Ethical Behavior and Organizational Commitment

Besides external factors arising from superiors, associates and workplace climate, employees’ behavior is further determined by their internal values and feelings (Pio & Lengkong, 2020). Organizational commitment represents the psychological bond between employees and the firm, comprising senses of attachment, loyalty and faith in organizational values (Raji, Ladan, Alam & Idris, 2021; Yang & Wei, 2018). It consists of three dimensions, which are normative (obligatory), continuance (cost-related) and affective (feelings-related) (Allen & Meyer, 1990). However, the current study focuses on affective commitment as it is the most studied and robust dimension which provides finest comprehension of how employees’ behaviors are formed (Lau et al., 2017; Usman, Javed, Shoukat & Bashir, 2021). Conceptually, affective commitment illustrates employees' emotional attachment that results from personal involvement and interests and values shared with the company (Tang & Vandenberghe, 2020). It has a significant impact on employee workplace behaviors and choices, including job retention and turnover intentions, timeliness, organizational citizenship behaviors, and work efficiency and performance (Dhar, 2015; Hunter & Thatcher, 2007; Jaiswal & Dhar, 2016; Khan, Jianguo, Hameed, Mushtaq & Usman, 2018; Pool & Pool, 2007; Wasti & Can, 2008).

Ethical leaders can positively uplift employees’ workplace attitudes and attachments (Asif, Miao, Jameel, Manzoor & Hussain, 2020). Once again, social learning and social exchange theories offer baselines for how ethical leaders shape followers’ commitment. Leaders’ role models of trustworthiness, justice and devotion to organizational values standardize affiliated feelings with the company among subordinates (Brown et al., 2005; Zhang & Jiang, 2020). Reciprocity attribute of social exchange additionally drives employees’ loyalty and emotional bond in response to leader’s courtesy and attentiveness to followers’ well-being (Blau, 1964; Gouldner, 1960). In line with these expectations, a study conducted by Beeri et al. (Beeri, Dayan, Vigoda-Gadot & Werner, 2013) found positive impacts ethical leaders imposed on employees’ organizational commitment. Similarly, in an experiment by Aryati et al. (Aryati et al., 2018), organizational commitment was discovered to develop out of ethical leadership and act as a mediator between ethical leadership and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior. Therefore, in accordance with former research, we make the following hypothesis:

H6: Ethical leadership has positive influence on organizational commitment.

According to former research, employees’ emotional attachment catalyzes faith in organizational objectives and values, as well as strong engagement in supportive behaviors beyond obligation that benefit the company (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). Organizational commitment also encourages continual improvement and growth in workplace practices, so that they may add to the company's productivity and benefits (Wasti & Can, 2008). Hence, we can expect that subordinates with high levels of commitment would have greater tendency to carry out ethical conducts for the well-being of their firms. Besides suggested negative relationship between employees’ commitment and their unethical conducts (Aryati et al., 2018; Usman et al., 2021), empirical research has confirmed the positive association between organizational commitment and workers’ desirable behaviors, such as organizational citizenship and pro-social behaviors (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch & Topolnytsky, 2002; Vandenberghe, Bentein & Stinglhamber, 2004; Yang & Wei, 2018). Hence, from these descriptions, we reason that:

H7: Organizational commitment has positive influence on employee’s ethical behavior.

Measurement Items

Five points Likert-scale was applied to measure the variables in the research model, from 1 representing for strongly disagree to 5 for strongly agree. All measurement items were adapted from previous empirical research and had been extensively used by many scholars.

Ethical Leadership (EL). We adopted 07 items from Cheng et al.(Cheng et al., 2019), whose research had also adapted questions from Brown et al. (Brown et al., 2005) to assess levels of ethics among leaders in organizations. These items include “My manager: Listens to what department employees have to say/Conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner/Has the best interests of employees in mind/Makes fair and balanced decisions/Can be trusted/Discusses business ethics or values with employees/Sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics.”

Ethical Behavior (EB). This variable was measured using 07 items selected out of study by Al Halbusi, Williams, Ramayah, et al (Al Halbusi et al., 2020) so that the chosen questions are appropriate for Vietnamese respondents. The items are: “I take responsibility for my own errors/I use company services appropriately and not for personal use/I keep confidential information confidential/I take the appropriate amount of time to do a job/I report others’ violation of company policies and rules/I lead my subordinates to behave ethically/I complete time, quality, quantity reports honestly”

Coworker Ethical Behavior (CEB). We further adopted 03 items from Mayer et al. (Mayer, Nurmohamed, Treviño, Shapiro & Schminke, 2013) to reflect how ethical the respondents’ colleagues are. The items are: “My coworkers support me in following my company’s standards of ethical behavior/My coworkers carefully consider ethical issues when making work-related decisions/Overall, my coworkers set a good example of ethical business behavior”.

Perceived Organizational Politics (POP). We again utilized 04 items from Cheng et al. (Cheng et al., 2019) to demonstrate the employees’ perception of political levels in their organizations. These items include: “People in this organization attempt to build themselves up by tearing others down/Sometimes it is easier to remain quiet than to fight the system./It is safer to think what you are told than to make up your own mind./When it comes to pay raise and promotion decisions, policies are irrelevant.”

Organizational Commitment (OC). We adopted 04 items from Meyer et al.(Meyer, Allen & Smith, 1993)showing the affective commitment that individuals feel towards their firms. The items are: “I would be happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization./I really feel that this organization’s problems are my own./I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organization./This organization has a great deal of personal meaning to me.”

Data Collection Procedure

It is vital that suitable population be selected for research in the business and management fields (Bell et al., 2018). Since the current study aims to clarify how ethical leaders as well as perception of organizational politics, coworkers and employees’ own commitment to the organization affect their ethical behaviors, employees are therefore the most appropriate respondents. It should be noted that workers were carefully selected based on their current job positions, in which only people holding titles of middle managers and below were chosen.

The target companies vary in their business fields, ranging from banking, manufacturing to logistics and services industries, etc. By collecting data from various organizations, the study achieves great numbers of respondents and offers more comprehensive and reflective results than studies with restricted data collection in few organizations (Zehir & Erdogan, 2011). This approach also allows examination of sensitive topics such as ethical behavior as it reduces influences of social desirability on altering the results (Al Halbusi et al., 2020).

After careful modification and consultation from experts in the business administration and social science fields, questionnaires were then distributed to the target respondents over the link of Google form. The survey distribution was conducted over the course of three consecutive months, from January 2021 to March 2021. Using non-probability convenient and snowball sampling techniques, the study obtained the data of 263 employees working at 20 different joint stock companies in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. We have also received invaluable support from managers and executives of these firms for further distribution to their subordinates and coworkers. It should be noted that only individuals possessing titles of middle managers and below were selected for the survey.

Data Analysis Methods

PLS-SEM method was chosen as the primary analytical tool. For starters, PLS-SEM was shown to be an excellent fit for a model with high dimensionality with a complex structure and many connections between components (Hair, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2017). Second, If distributional assumptions are missing in certain social science investigations, it has been proposed that using PLS-SEM will obviously benefit researchers (Hair, Risher, Sarstedt & Ringle, 2019). Finally, PLS-SEM does not require overly large samples and is well suited to predictive research (Hair et al., 2019). As the current study proposing new correlations and mechanisms among variables, this application is sensible. Smart-PLS would be utilized for analysing the measurement model and structural model of this research.

Results

Using PLS-SEM, 2-steps procedure for data analysis is recommended (Hair Jr, Sarstedt, Hopkins & Kuppelwieser, 2014). The study first assesses the measurement model (outer model), which entails examining the links between latent variables and their indicators (reliability and validity testing). The proposed hypotheses between constructs are then investigated using the structural model (inner model) (Caldeira & Kastenholz, 2018).

Measurement Model

| Table 1 Summary of Key Indicators |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent variables | Items | Mean | SD | Loadings | VIF | Cronbach's alpha | Rho_A | Composite reliability | AVE |

| Threshold | = 0.7 | = 0.6 | = 0.7 | = 0.7 | = 0.5 | ||||

| Ethical Leadership (EL) | EL1 | 4.11 | 0.80 | 0.755 | 1.861 | 0.880 | 0.882 | 0.910 | 0.628 |

| EL3 | 4.19 | 0.76 | 0.806 | 2.099 | |||||

| EL4 | 3.94 | 0.96 | 0.812 | 2.267 | |||||

| EL5 | 4.06 | 0.89 | 0.818 | 2.257 | |||||

| EL6 | 3.75 | 0.97 | 0.704 | 1.643 | |||||

| EL7 | 3.98 | 0.89 | 0.850 | 2.397 | |||||

| Ethical Behavior (EB) | EB1 | 4.55 | 0.65 | 0.757 | 1.879 | 0.851 | 0.868 | 0.888 | 0.571 |

| EB2 | 4.25 | 0.79 | 0.778 | 1.867 | |||||

| EB3 | 4.57 | 0.74 | 0.702 | 1.697 | |||||

| EB4 | 4.27 | 0.74 | 0.743 | 1.759 | |||||

| EB6 | 4.11 | 0.83 | 0.784 | 1.669 | |||||

| EB7 | 4.38 | 0.72 | 0.766 | 1.762 | |||||

| Coworker Ethical Behavior (CEB) | CEB1 | 3.87 | 0.84 | 0.857 | 1.899 | 0.830 | 0.830 | 0.898 | 0.746 |

| CEB2 | 3.84 | 0.87 | 0.878 | 2.039 | |||||

| CEB3 | 3.78 | 0.89 | 0.855 | 1.805 | |||||

| Perceived Organizational Politics (POP) | POP1 | 2.30 | 1.16 | 0.870 | 1.649 | 0.810 | 0.902 | 0.870 | 0.628 |

| POP2 | 2.94 | 1.21 | 0.799 | 1.811 | |||||

| POP3 | 3.17 | 1.10 | 0.771 | 1.623 | |||||

| POP4 | 2.95 | 1.07 | 0.721 | 1.569 | |||||

| Organizational Commitment (OC) | OC1 | 3.46 | 0.96 | 0.812 | 2.013 | 0.847 | 0.855 | 0.898 | 0.687 |

| OC2 | 3.88 | 0.89 | 0.800 | 1.721 | |||||

| OC3 | 3.71 | 0.89 | 0.904 | 2.810 | |||||

| OC4 | 3.57 | 0.95 | 0.795 | 1.748 | |||||

First, for evaluation of correlations between latent constructs and indicators, Cronbach’s α of each variable should surpass the threshold of 0.6 to ensure items reliability. Furthermore, any indications with outer loadings less than the 0.7 cut-off value should be removed (Henseler, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2012). All constructions' composite reliability (or Rho A) is more than 0.7, indicating good internal consistency. All factor AVE values also exceed 0.5, exhibiting good levels of convergent validity. (See Table 1)

| Table 2 Fornelllarcker Criterion |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEB | EB | EL | OC | POP | |

| CEB | 0.864 | ||||

| EB | 0.494 | 0.755 | |||

| EL | 0.558 | 0.440 | 0.792 | ||

| OC | 0.499 | 0.514 | 0.561 | 0.829 | |

| POP | -0.056 | -0.033 | -0.211 | -0.121 | 0.792 |

| Table 3 HTMT Criterion |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEB | EB | EL | OC | POP | |

| CEB | |||||

| EB | 0.567 | ||||

| EL | 0.648 | 0.489 | |||

| OC | 0.597 | 0.588 | 0.646 | ||

| POP | 0.086 | 0.087 | 0.231 | 0.138 | |

For discriminant validity, the study followed Fornell and Larcker (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) standards and HTMT requirements. For the first criterion, the square roots of the AVE in diagonal of each construct are significantly above the correlation coefficient of that construct with other components, as seen in Table 2. Additionally, HTMT advises that the ratio between the mean value of item correlations across constructs and the mean of correlations for items in a single construct should not exceed 0.85 (Henseler, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2015). Table 3 shows that all values are below 0.7, justifying the presence of discriminant validity.

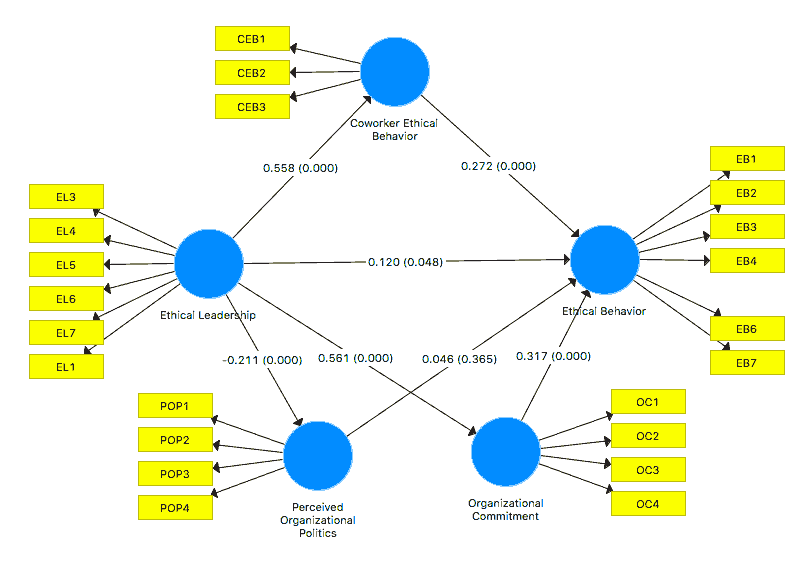

Structural Model

Inner model is examined and proposed hypotheses are tested using 10,000 samples bootstrapping to obtain the significance values in 2-tailed t-test (Caldeira & Kastenholz, 2018). As shown by Table 4, six out of seven proposed correlations are accepted at 5% significance level, with only H5 is not supported. Results of path analysis and hypothesis testing are visually summarized in Figure 2 below.

| Table 4 Pls-Sem Path Coefficients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Sample (O) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | Results | |

| H1 | 0.120 | 0.061 | 1.975 | 0.048* | Supported |

| H2 | 0.558 | 0.049 | 11.323 | 0.000** | Supported |

| H3 | 0.272 | 0.065 | 4.210 | 0.000** | Supported |

| H4 | -0.211 | 0.059 | 3.594 | 0.000** | Supported |

| H5 | 0.046 | 0.051 | 0.906 | 0.365 | Not Supported |

| H6 | 0.561 | 0.050 | 11.268 | 0.000** | Supported |

| H7 | 0.317 | 0.060 | 5.239 | 0.000** | Supported |

Q-squared test was also employed in this study to estimate the model’s predictive relevance. Positive values of Q^2 for all factors confirm good construction of the variables and predictive relevance of the model (Hair et al., 2017). In addition, the model is considered to possess goodness of fit when its value of standardized root means square residual (SRMR) falls below the threshold of 0.08. With SRMR=0.073, the model shows plausibility and good fit in explaining the constructs (Hair et al., 2017; Henseler, Hubona & Ray, 2016)

Discussion

Applying Social learning theory and Social exchange theory in explaining correlations among constructs, the study investigates the consequences of ethical leadership and how these outcomes enhance ethical conducts in organizations. Overall, our findings give support towards the proposed linkages.

First, consistent with Lu & Lin (Lu & Lin, 2014) and Demirtas (Demirtas, 2015), the study found significant theoretical link between ethical leadership and ethical behaviour among employees. Leaders provide social cues on expected and proper actions at work through role modelling, which organizational members can learn from (Gan, 2018). Second, in line with notions proposed in former empirical studies (O’Fallon & Butterfield, 2012; Robinson et al., 2014), the study’s findings depict positive associations between ethical leadership and coworker ethical behaviour as well as these their influences on employees’ behavioural tendency, confirming the role of coworkers as additional learning source for socially acceptable behaviours. Employees are constantly surrounded by moral signs and thus motivated to participate in ethical conducts that help them align themselves with recognized social preferences and values from colleagues. Third, in line with results in Cheng et al. (Cheng et al., 2019)’s study, ethical leaders are proved to have the ability of altering individuals outcomes by shaping the organizational climate, in this case, level of organizational politics in particular (Demirtas & Akdogan, 2015). Organizational politics are generally perceived as negative organizational setting and assumed to impose detrimental effects on organizations and individuals (Rosen et al., 2014). As ethical leaders help to promote transparency and integrity rather than political competition and self-serving acts, perception of politics among employees is decreased. Surprisingly, the findings demonstrate that low levels of POP do not encourage employees to behave more ethical, which is far different from previous research (Bergeron & Thompson, 2020; Cheng et al., 2019). In other words, as the organizational politics increase, employees are not necessarily discouraged and become less ethical. According to Başar et al. (Başar et al., 2018), when employees acknowledge political acts carried out by others around, they may choose to have negative responses (e.g. leaving their jobs, acting unethical in return, whistle blowing), ignore the political games and not interfere with it, or become a part and exercise political practices. Characteristics of high power distance and collectivism in Vietnamese firms have made it unusually for employees to raise their voice or react aggressively towards counterproductive behaviours (Nguyen, Teo & Dinh, 2020). The possible explanation is that as Vietnamese workers acknowledge the existence of organizational politics, they would choose to stay out of the competition and yet not react aggressively for fear of provoking any influential individuals and getting discharged. Given most respondents are above or around their thirties with long years of working, there is high probability of hesitation and resistance against changing occupation (Emiroğlu, Akova & Tanrıverdi, 2015). Hence, it is sensible neglect the situation in the pursuit of securing their positions. Although POP does not lead to immediate job resignations or negative responses among Vietnamese employees, it may catalyse psychological distress and decreased working performances in the long-term (Nguyen, Teo, Grover & Nguyen, 2019; Vigoda-Gadot, 2007). Finally, our study identifies organizational commitment as the underlying mechanism which links ethical leadership and employees’ ethical behaviours, aligning with former studies (Asif et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2018). Ethical leaders are proven to advance the implementation of ethical conducts by creating affective connection between employees and the organization. Loyalty and emotional bond developed out of leader’s courtesy and morality would consequently direct followers to act upon firms’ and managers’ well-being.

Theoretical Implication

In the following respects, the current study adds to the existing literature on ethical leadership and employee ethical behaviour. First, the study supports the favourable relationship between ethical leadership and ethical behaviour among employees by combining the theoretical frameworks of social learning and social exchange. This application deepens knowledge of ethical leadership's operation and functionality in terms of ethical workplace practices. Second, our study incorporates additional variables, including coworker ethical behaviour, perceived organizational politics and organizational commitment, to comprehensively demonstrate the underlying mechanisms linking ethical leadership to followers’ ethical acts. Notably, despite existing high levels of politics in Vietnamese firms, there has been no similar research on how this negative organizational setting functions under different forms of leadership as well as its impacts on workplace behaviours. With unexpected findings about the relationship between POP and ethical behaviours, the study shed lights on employees’ psychological and ethical responses to the present political games. Finally, unlike earlier empirical studies undertaken in Western countries, this study was conducted in a developing country, allowing for the generalization of the analysed connections across multiple cultural and national settings.

Practical Implication

The outcomes of the study emphasize the importance of leaders as the one primary source of ethical behaviour for subordinates. The strong link between ethical leadership and ethical behaviours among employees demonstrates the importance of selecting and training ethical leaders. Moral qualities should be more important selection factor for future managers in Vietnamese enterprises. Candidates for senior jobs should be thoroughly assessed in terms of their previous performance and honesty. Furthermore, periodic trainings on issues such as how to express ethical ideals, promote and reward ethical behaviour, and charismatically motivate others areessential.

Ethical leaders are also revealed to indirectly influence followers’ behaviours by first affecting their coworkers and people who are close to them. These findings suggest widespread codes of ethics and organizational standards that are followed by all members of the organization. Employees can be informed about guidelines on caring for one another, sharing in decision-making, treating people with respect, and listening to others' views and concerns, among other things, through frequent internal communication or the company's declared ideals and values.

Leaders may strive to foster honest communication and responses of others by providing less political and more ethical working environment. Enhancing transparent individuals’ roles and responsibilities with fair performance evaluation would prevent political practices to develop in organizations. Establishment of regulations against self-interest activities while promoting participation in decision-making processes helps to diminish the hierarchy boundaries between leaders and followers. Open discussion and comments with anonymous box for comments, 360-degree feedback system and hotline for reporting workplace misconducts are also necessary.

Finally, ethical leaders generate emotional attachment among employees to the organization by demonstrating real concern for their well-being and growth, motivating them to conduct supportive and ethical behaviours. Employees would experience more appreciation and meaningfulness in their professions if ethical leaders create a healthy working culture where employees' innovation and contributions are acknowledged, their ideas and views are completely heard, and their abilities and potentials are fully realized. Fair rewards and recognition for employees, frequent open dialogue, clear and suitable organizational goals and expectations, and assistance for their career growth and on-going specialized trainings are all part of these fundamental developments.

Conclusion

Our research adds to the current body of knowledge about ethical behaviour by incorporating new factors into the conceptual model. From 263 responses collected from joint stock companies in Ho Chi Minh city, the study unfolds the positive impacts of ethical leadership and how these outcomes alter employees’ behaviours. Specifically, ethical leaders promote ethical behaviours among all members of the organization and their emotional commitment, resulting in higher tendency towards supportive and moral conducts. The study further suggests political environment as a negative organizational setting that prevents individuals from having honest communication and responses. These findings suggest that transparent organizational rules, ongoing training and improvement in ethical behaviors, as well as open debate and measures to improve honest reports, should all be considered.

Limitations

While the study contributes to the understanding about mechanisms linking ethical leadership to employees’ ethical behaviors, it contains several limitations. First, since the current study utilized cross-sectional data from only joint stock companies to indicate the correlations between variables, causal inferences cannot be made about these relationships due to possible changes over time of these factors and across different organizational types. Therefore, future work should apply longitudinal research designs with other groups of respondents to make generalized conclusion and address the issue in more causal perspectives. Second, our study was relied on a self-reported survey, which may exacerbate the problem of compromised consistency of these data as ethical issues are sensitive and complex subjects for people to debate and put out honest measurement. Hence, future research should collect additional feedback on employees' behaviour from a variety of sources, such as managers and coworkers.

References

Afsar, B., & Umrani, W.A. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 109–125.

Al Halbusi, H., & Hamid, F. (2018). Antecedents influence turnover intention: Theory extension. Journal of Organizational Behavior Research, 3(2), 287–304.

Al Halbusi, H., Williams, K.A., Mansoor, H.O., Hassan, M.S., & Hamid, F.A.H. (2020). Examining the impact of ethical leadership and organizational justice on employees’ ethical behavior: Does person–organization fit play a role?Ethics and Behavior, 30(7), 514–532.

Al Halbusi, H., Williams, K.A., Ramayah, T., Aldieri, L., & Vinci, C.P. (2020). Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees’ ethical behavior: The moderating role of person–organization fit. Personnel Review, 50(1), 159–185.

Arnold, D.G., Beauchamp, T.L., & Bowie, N.E. (2019). Ethical theory and business (10th edition). Cambridge University Press.

Aryati, A.S., Sudiro, A., Hadiwidjaja, D., & Noermijati, N. (2018). The influence of ethical leadership to deviant workplace behavior mediated by ethical climate and organizational commitment. International Journal of Law and Management, 60(2), 233–249.

Asif, M., Miao, Q., Jameel, A., Manzoor, F., & Hussain, A. (2020). How ethical leadership influence employee creativity: A parallel multiple mediation model. Current Psychology, 1–17.

Asrar-ul-Haq, M., Ali, H.Y., Anwar, S., Iqbal, A., Iqbal, M.B., Suleman, N., … & Haris-ul-Mahasbi, M. (2019). Impact of organizational politics on employee work outcomes in higher education institutions of Pakistan: Moderating role of social capital. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 8(2), 185–200.

Avey, J.B., Palanski, M.E., & Walumbwa, F.O. (2011). When leadership goes unnoticed: The moderating role of follower self-esteem on the relationship between ethical leadership and follower behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(4), 573–582.

Babalola, M.T., Stouten, J., Camps, J., & Euwema, M. (2019). When do ethical leaders become less effective? The moderating role of perceived leader ethical conviction on employee discretionary reactions to ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(1), 85–102.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Barrick, M.R., Mount, M.K., & Li, N. (2013). The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics.Academy of Management Review, 38(1), 132–153.

Basar, U., Sigri, Ü., & Nejat Basim, H. (2018). Ethics lead the way despite organizational politics. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 7(1), 81–101.

Batabyal, S.K., & Bhal, K.T. (2018). Perceived ethicality of political behaviours in organisations: A constructivist grounded theory study. Journal for Global Business Advancement, 11(6), 706–725.

Beeri, I., Dayan, R., Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Werner, S.B. (2013). Advancing ethics in public organizations: The impact of an ethics program on employees’ perceptions and behaviors in a regional council. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(1), 59–78.

Bergeron, D.M., & Thompson, P.S. (2020). Speaking up at work: The role of perceived organizational support in explaining the relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and voice behavior. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 56(2), 195–215.

Blau, P. (1964). Power and exchange in social life. New York: J Wiley & Sons.

Brown, M.E., & Treviño, L.K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brown, M.E., & Treviño, L.K. (2014). Do role models matter? An investigation of role modeling as an antecedent of perceived ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(4), 587–598.

Brown, M.E., Treviño, L.K., & Harrison, D.A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Burns, J.M. (1998). Transactional and transforming leadership. Leading Organizations, 5(3), 133–134.

Caldeira, A.M., & Kastenholz, E. (2018). It’s so hot: Predicting climate change effects on urban tourists’ time–space experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(9), 1516–1542.

Caruso, E.M., & Gino, F. (2011). Blind ethics: Closing one’s eyes polarizes moral judgments and discourages dishonest behavior. Cognition, 118(2), 280–285.

Cheng, J., Bai, H., & Yang, X. (2019). Ethical leadership and internal whistle blowing: A mediated moderation model. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(1), 115–130.

Demirtas, O. (2015). Ethical leadership influence at organizations: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(2), 273–284.

Demirtas, O., & Akdogan, A.A. (2015). The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(1), 59–67.

Dhar, R.L. (2015). Service quality and the training of employees: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Tourism Management, 46, 419–430.

Emiroglu, B.D., Akova, O., & Tanriverdi, H. (2015). The relationship between turnover intention and demographic factors in hotel businesses: A study at five star hotels in Istanbul. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 207, 385–397.

Hair Jr, J., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388.

Gan, C. (2018). Ethical leadership and unethical employee behavior: A moderated mediation model. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46(8), 1271–1283.

Gino, F., Schweitzer, M.E., Mead, N.L., & Ariely, D. (2011). Unable to resist temptation: How self-control depletion promotes unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 191–203.

Gotsis, G.N., & Kortezi, Z. (2010). Ethical considerations in organizational politics: Expanding the perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(4), 497–517.

Gouldner, A.W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178.

Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publication, Inc.

Hair, J.F., Risher, J.J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C.M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24.

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P.A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2012). Using partial least squares path modeling in advertising research: Basic Concepts and Recent Issues. (E. Elgar, Ed.), Handbook of Research on International Advertising. Cheltenham, UK – Northampton, MA, USA.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

Huang, I.C., Chuang, C.H.J., & Lin, H.C. (2003). The role of burnout in the relationship between perceptions off organizational politics and turnover intentions. Public Personnel Management, 32(4), 519–531.

Hunter, L.W., & Thatcher, S.M.B. (2007). Feeling the heat: Effects of stress, commitment, and job experience on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 953–968.

Jaiswal, D., & Dhar, R.L. (2016). Impact of perceived organizational support, psychological empowerment and leader member exchange on commitment and its subsequent impact on service quality. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 65(1), 58–79.

Kacmar, K.M., Andrews, M.C., Harris, K.J., & Tepper, B.J. (2013). Ethical leadership and subordinate outcomes: The mediating role of organizational politics and the moderating role of political skill. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(1), 33–44.

Kacmar, K.M., Bachrach, D.G., Harris, K.J., & Zivnuska, S. (2011). Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 633–642.

Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D. N., & de Hoogh, A. H. B. (2013). Ethical leadership and followers’ helping and initiative: The role of demonstrated responsibility and job autonomy. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(2), 165–181.

Karatepe, O.M., Babakus, E., & Yavas, U. (2012). Affectivity and organizational politics as antecedents of burnout among frontline hotel employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(1), 66–75.

Karim, S., & Nadeem, S. (2019). Understanding the unique impact of dimensions of ethical leadership on employee attitudes. Ethics & Behavior, 29(7), 572–594.

Kennedy, J.C. (2002). Leadership in Malaysia: Traditional values, international outlook. In Academy of Management Executive, Academy of Management, 16, 15–26.

Khan, M.A.S., Jianguo, D., Hameed, A.A., Mushtaq, T.U.L., & Usman, M. (2018). Affective commitment foci as parallel mediators of the relationship between workplace romance and employee job performance: A cross-cultural comparison of the People’s Republic of China and Pakistan. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 11, 267–278.

Kim, A., Kim, Y., Han, K., Jackson, S.E., & Ployhart, R.E. (2017). Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. Journal of Management, 43(5), 1335–1358.

Kish-Gephart, J.J., Harrison, D.A., & Treviño, L.K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1.

Ko, C., Ma, J., Bartnik, R., Haney, M.H., & Kang, M. (2018). Ethical leadership: An integrative review and future research agenda. Ethics & Behavior, 28(2), 104–132.

Lau, P.Y.Y., Tong, J.L.Y.T., Lien, B.Y.H., Hsu, Y.C., & Chong, C.L. (2017). Ethical work climate, employee commitment and proactive customer service performance: Test of the mediating effects of organizational politics. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 35, 20–26.

Letwin, C., Wo, D., Folger, R., Rice, D., Taylor, R., Richard, B., & Taylor, S. (2016). The “right” and the “good” in ethical leadership: Implications for supervisors’ performance and promotability evaluations. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(4), 743–755.

Lin, C.P., Liu, N.T., Chiu, C.K., Chen, K.J., & Lin, N.C. (2019). Modeling team performance from the perspective of politics and ethical leadership. Personnel Review, 48(5), 1357–1380.

Lu, C.S., & Lin, C.C. (2014). The effects of ethical leadership and ethical climate on employee ethical behavior in the international port context. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(2), 209–223.

Mayer, D.M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R.B. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13.

Mayer, D.M., Kuenzi, M., & Greenbaum, R.L. (2010). Examining the link between ethical leadership and employee misconduct: The mediating role of ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(1), 7–16.

Mayer, D.M., Nurmohamed, S., Treviño, L.K., Shapiro, D.L., & Schminke, M. (2013). Encouraging employees to report unethical conduct internally: It takes a village. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 121(1), 89–103.

Mayer, D.M., Nurmohamed, S., Treviño, L.K., Shapiro, D.L., Schminke, M., Meyer, J.P., … & Lin, C.C. (2014). The effects of ethical leadership and ethical climate on employee ethical behavior in the international port context. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(2), 209–223.

Meyer, J.P., Allen, N.J., & Smith, C.A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551.

Mitchell, M.S., Reynolds, S.J., & Treviño, L.K. (2017). The study of behavioral ethics within organizations. Personnel Psychology, 70(2), 313–314.

Mo, S., & Shi, J. (2018). The voice link: A moderated mediation model of how ethical leadership affects individual task performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(1), 91–101.

Neubert, M.J., Carlson, D.S., Kacmar, K.M., Roberts, J.A., & Chonko, L.B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field.Journal of Business Ethics, 90(2), 157–170.

Neves, P., Almeida, P., & Velez, M.J. (2018). Reducing intentions to resist future change: Combined effects of commitment-based HR practices and ethical leadership. Human Resource Management, 57(1), 249–261.

Nguyen, D.T.N., Teo, S.T.T., & Dinh, K.C. (2020). Social support as buffer for workplace negative acts of professional public sector employees in Vietnam. Public Management Review, 22(1), 6–26.

Nguyen, D.T.N., Teo, S.T.T., Grover, S.L., & Nguyen, N.P. (2019). Respect, bullying, and public sector work outcomes in Vietnam. Public Management Review, 21(6), 863–889.

Nguyen, V.P., Trieu, D.X.H., Ton, N.H.U., Dinh, Q.C., & Tran, Q.H. (2021). Impacts of career adaptability, life meaning, career satisfaction, and work volition on level of life satisfaction and job performance. Humanities and Social Sciences Letters, 9(1), 96–110.

O’Fallon, M.J., & Butterfield, K.D. (2012). The influence of unethical peer behavior on observers’ unethical behavior: A Social Cognitive Perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(2), 117–131.

Ofori, G. (2009). Ethical leadership: Examining the relationships with full range leadership model, employee outcomes, and organizational culture. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(4), 533–547.

Paillé, P., Grima, F., & Dufour, M.È. (2015). Contribution to social exchange in public organizations: Examining how support, trust, satisfaction, commitment and work outcomes are related. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(4), 520–546.

Pio, R.J., & Lengkong, F.D.J. (2020). The relationship between spiritual leadership to quality of work life and ethical behavior and its implication to increasing the organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Management Development, 39(3), 293–305.

Pool, S., & Pool, B. (2007). A management development model: Measuring organizational commitment and its impact on job satisfaction among executives in a learning organization. Journal of Management Development, 26(4), 353–369.

Raji, I.A., Ladan, S., Alam, M.M., & Idris, I.T. (2021). Organisational commitment, work engagement and job performance: empirical study on Nigeria’s public healthcare system. Journal for Global Business Advancement, 14(1), 115–137.

Rana, S., & Sharma, S.K. (2016). A review on the state of methodological trends in international marketing literature. Journal for Global Business Advancement, 9(1), 90–107.

Resick, C.J., Martin, G.S., Keating, M.A., Dickson, M.W., Kwan, H.K., & Peng, C. (2011). What ethical leadership means to me: Asian, American, and European perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(3), 435–457.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714.

Robinson, S.L., Wang, W., & Kiewitz, C. (2014). Coworkers behaving badly: The impact of coworker deviant behavior upon individual employees. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 123–143.

Rosen, C.C., Ferris, D.L., Brown, D.J., Chen, Y., & Yan, M. (2014). Perceptions of organizational politics: A need satisfaction paradigm. Organization Science, 25(4), 1026–1055.

Rosen, C.C., Levy, P.E., & Hall, R.J. (2006). Placing perceptions of politics in the context of the feedback environment, employee attitudes, and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 211.

Stouten, J., Baillien, E., Van den Broeck, A., Camps, J., De Witte, H., & Euwema, M. (2010). Discouraging bullying: The role of ethical leadership and its effects on the work environment. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(1), 17–27.

Tang, W.G., & Vandenberghe, C. (2020). Is affective commitment always good? A look at within-person effects on needs satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119.

Thomas, J.R. (2014). Shades of green: A critical assessment of greenwashing in social and environmental business performance reports. Journal for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 7(3), 245–252.

Treviño, L.K., Den Nieuwenboer, N.A., & Kish-Gephart, J.J. (2014). (Un) ethical behavior in organizations. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 635–660.

Usman, M., Javed, U., Shoukat, A., & Bashir, N.A. (2021). Does meaningful work reduce cyberloafing? Important roles of affective commitment and leader-member exchange. Behaviour and Information Technology, 40(2), 206–220.

Vandenberghe, C., Bentein, K., & Stinglhamber, F. (2004). Affective commitment to the organization, supervisor, and work group: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 47–71.

Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2007). Leadership style, organizational politics, and employees’ performance: An empirical examination of two competing models. Personnel Review, 36(5), 661–683.

Waddock, S., Meszoely, G.M., Waddell, S., & Dentoni, D. (2015). The complexity of wicked problems in large scale change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(6), 993–1012.

Wasti, S.A., & Can, Ö. (2008). Affective and normative commitment to organization, supervisor, and coworkers: Do collectivist values matter?Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(3), 404–413.

Wiernik, B.M., & Ones, D.S. (2018). Ethical employee behaviors in the consensus taxonomy of counterproductive work behaviors. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 26(1), 36–48.

Yang, Q., & Wei, H. (2018). The impact of ethical leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: The moderating role of workplace ostracism. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 39(1), 100–113.

Yidong, T., & Xinxin, L. (2013). How ethical leadership influence employees’ innovative work behavior: A perspective of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(2), 441–455.

Zehir, C., & Erdogan, E. (2011). The association between organizational silence and ethical leadership through employee performance. In Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 1389–1404, Elsevier.

Zhang, L., & Jiang, H. (2020). Exploring the process of ethical leadership on organisational commitment: The mediating role of career calling. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 30(3), 231–235.

Received: 24-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-10462; Editor assigned: 27-Feb-2022; PreQC No. JLERI-21-10462(PQ); Reviewed: 14-Mar-2022, QC No. JLERI-21-10462; Revised: 20-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-10462(R); Published: 24-Mar-2022