Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 2

Transforming Obstacles Into Supporters In An Attempt To Promote Inclusive Education

Constantia A Charalampous, Neapolis University Pafos Cyprus

Christos D Papademetriou, Neapolis University Pafos Cyprus

Masouras A, Neapolis University Pafos Cyprus

Abstract

The objective of this research is to identify the barriers that the school community faces in trying to include pupils identified as having special educational needs (SEN). We recommend the application of the ��?Intermediate �?nverted Leadership� (IIL) (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2019), an innovative educational leadership model aiming at transforming the barriers into inclusive factors, based on the idea of decentralization, which can lead to creating inclusive school environments. To explore possible barriers and their conversion into inclusion factors, we used Mixed Methodology Action Research (MMAR), which was firstly proposed by Ivanova (2015), as an innovative research methodology. It combines mixed methodology with action research and allows reflection and change of practices used in a school by the teachers themselves. This research was conducted at a secondary school in Cyprus. The participants were consisted of 48 teachers, 4 parents of pupils identified as having SEN, 20 parents of pupils without disabilities, 3 pupils identified as having SEN and 80 pupils without SEN. Questionnaires, interviews, observations, focus groups and diaries were used as research tools. The results have shown that such an effort can lead one step closer to the inclusion of pupils identified as having SEN. So, we conclude that IIL model through effective emotional intelligence guidance can become even more inclusive.

Keywords

Intermediate inverted leadership, Inclusive education, Mixed methodology action research, Emotional intelligence, Pupils identified as having Special Educational Needs (SEN).

Introduction

According to the international literature, some pupils encounter sentiments of minimization, due to some of their characteristics (Scanlon, Barnes-Holmes, Shevlin and McGuckin, 2020). Pupils characterized as having SEN are usually some of them (Symeonidou, 2015). Over the last few years international research suggests applying inclusive philosophy as the most effective way to help in reducing the marginalization of pupils characterized as having SEN (Black, Bessudnov, Liu and Norwich, 2019).

By referring to inclusive education we mean the education of each child in his/her neighborhood school (Oluremi, 2015), focusing our attention on the environment where children are trained rather than on the child itself, but also on the quality of education provided to all children (Messiou, 2016), such as bilinguals, those in an alternative culture (Celoria, 2016), or religion, or differ due to their appearance.

Despite its positive-sounding connotations, in practice, has led to integration into the mainstream educational system for some pupils characterized as having SEN, while others are marginalized and excluded (Rodriguez and Garro-Gil, 2014). More specifically, according to Charalampous and Papademetriou (2018) secondary school in Cyprus is set up to include mixed-ability groups, which has presented enormous difficulties in both teaching and learning. Efforts have been made to supplement gde 3the education of pupils with certain learning difficulties via extra study groups, but this approach cannot work for all pupils characterized as having SEN (p.30).

Taking in mind the view that the school head teacher has an important role to play in school practice decisions, it is argued by the present article that the leadership model which is followed in any case may also help to ensure better implementation of the education of pupils experiencing any kind marginalization (Reinhartz and Beach, 2004).

Based on the above considerations, we have attempted to study the problem of the marginalization of pupils identified as special educational needs (SEN) in the light of the application of entrepreneurial and innovative practices that have the potential to create an inclusive school culture.

Literature Background

Inclusive education as an entrepreneurial and innovative practice

According to Aljohani (2015), innovation is the specific tool of entrepreneurs, by which they exploit change as an opportunity for a different business or service. By treating public education as a business, we could therefore claim that its problems could be resolved through the change and implementation of an innovative idea.

Over the last two decades there has been an attempt to implement the theory of promoting innovation in the field of education (Petridou and Glaveli, 2008). This effort has the potential to propose new approaches to issues that have remained unresolved for decades (Aithal and Aithal, 2015). According to Linnan and Li (2010) “education of innovation and entrepreneurship is a creative mode of talents cultivation based on quality-oriented education and thus is a beneficial complement to the reform and development of education.” (p.1).

The effort to apply inclusive education theory could not be characterized as entrepreneurship and innovation. This is because for at least two decades, there has been an intense effort worldwide to implement it successfully. At the same time, however, it is worth pointing out that practices used to promote inclusive education could be characterized as entrepreneurial and innovative. Specifically, schools could carry out innovative teacher preparation programs (Wolfberg, LePage and Cook, 2009) and developing “open and extensible learning systems, building cross-cultural networks of innovators and entrepreneurs, fostering cross-disciplinary communities of educators and experts” (Hamburg and Bucksch, 2017, p.168) and also using inclusive action research, as a research methodology that can help teachers reflect on their own teaching practices and behavior (Robinson, 2017).

International context

This strategy has been adopted by several European countries, including Cyprus (Manzano-García and Fernández, 2016). For example, by pursuing a one-way approach, Greece, according to Soulis, Georgiou, Dimoula and Rapti (2016) and Italy, according to Anastasiou, Kauffman and Di Nuovo (2015), promote Education for All (United Nations Education, 2005). This implies that it is the duty of mainstream education to facilitate comprehensive education (European Agency for Development of Special Needs Education, (EADSNE, 2007), integrating pupils in mainstream schools identified as having SEN (Priyanka and Samia, 2018). This view may be categorized as misleading, as Greek statistics suggest that students with disabilities and/or special education needs attend "special schools" or "pull-out programs / resource units" or "without additional help in the classroom" or "in the normal classroom with shadow teaching / parallel support" at least in Greece in 2018-2019 (European Commission, 2018). This does not, however, seem to be a "one-way approach".

In comparison, in Switzerland and Belgium, a two-track approach is adopted by educational policies, where pupils identified as having SEN are educated only in special schools or classes (EADSNE, 2007). On the other hand, there are countries that follow a multi-track strategy, with a range of programs and options between conventional and special education (EADSNE, 2007), such as the United Kingdom (Blackburn, 2016), France, Poland, Finland, Ireland. Studying these various approaches, we find that, on the one hand, countries that follow a two-track or multi-track approach agree that there are problems with a system of complete inclusion. On the other hand, it is not always clear that countries are effective in using inclusive practices after a one-way approach, as it also relies on the practice of each school for its implementation (Holmberg and Jeyaprathaban, 2016). The different approaches adopted by the above-mentioned countries, as well as the different views in academic literature, indicate that while for many years the discussion on inclusive education has been favored (Hornby, 2017), it is far from a settled affair. A number of obstacles are frequently impeded by the practical implementation of inclusion in the school setting (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2019); these are found in value, strength, practical and psychological barriers (Suleymanov, 2015). This finding led Ainscow (2005) to conclude that inclusive education is one of the most critical issues for education worldwide, while inclusive education can eradicate social exclusion and contribute to the improvement of school systems in general when it is successful (Ainscow, Booth and Dyson, 2006). Co-teaching and segregated teaching (Strogilos and King-Sears, 2018) will lead to developing an inclusive school atmosphere for all pupils (Strogilos, 2018).

Cyprus context

According to Charalampous and Papademetriou (2018) “the debate on inclusive education in Cyprus is ongoing. Inclusive education was introduced into the Cypriot educational system via the "Law of Education of Children with Special Needs of 1999" (Ν. 113(I)/99, hereinafter ‘the 1999 law’). Subsequent amendments to the legislation were implemented in 2001 (Ν. 69(I)/2001, hereinafter ‘the 2001 regulation’), in 2013 (via Circular 416/2013, hereinafter ‘the 2013 circular’), and in 2014, via updated legislation (Ν.87(I)/2014, hereinafter ‘the 2014 law’)” (p.30). What has been witnessed is that, despite efforts to make the educational system inclusive, Cyprus has instead applied integration of pupils characterized as having SEN (Symeonidou and Phtiaka, 2009).

Obstacles towards implementing inclusion

During the past decades, many researchers have dealt with the subject of synergy between inclusive education and educational leadership (Buli-Holmberg, Nilsen and Skogen, 2019). On the one hand, inclusive education aims at preventing the marginalisation of children identified as having SEN (Messiou, 2016). On the other hand, educational leadership examines the parameters pertaining to the leadership and management of a school organisation (Kurland, 2018).

The two concepts are identified by common targeting, as educational leadership is the key tool an organisation needs in order to fulfil its targets (Chaudhry and Javed, 2012) and, therefore, a major prerequisite for the success of inclusive education, since it identifies and enhances factors that contribute to school improvement (Wanda, 2016).

That said, their common course towards school improvement is blocked by factors that impede the implementation of the inclusive philosophy (Garrote, Sermier Dessemontet, Moser Opitz, 2017) one of these factors possibly being the centralist nature of the Cypriot educational system (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2018).

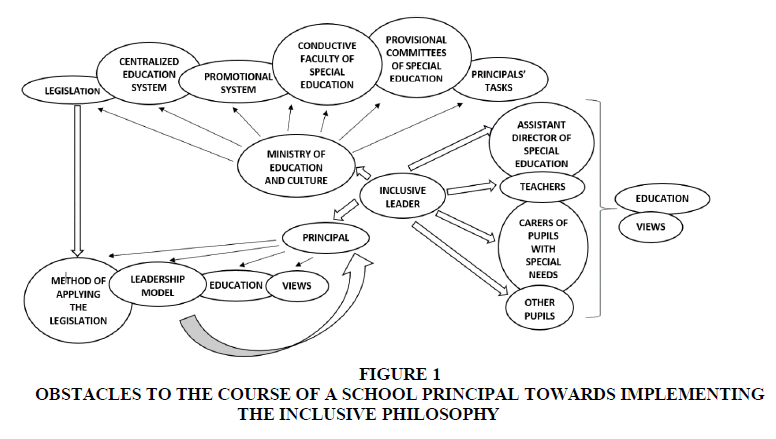

The following figure 1, which was created in the context of this research, illustrates the obstacles to the course of a school principal towards implementing the inclusive philosophy.

Figure 1 Obstacles to the Course of a School Principal Towards Implementing the Inclusive Philosophy

Analyzing the above figure, we can see that, on his way to create an inclusive school, a leader is faced with six main obstacles: school principals himself, who act as the heads of the schools and have specific duties and jurisdictions (sometimes limited authorities and autonomy) and in particular, their inadequate knowledge (Clitton, 2013), as well as their views (Jahnukainen, 2015); the Ministry of Education and Culture (legislation and budget); the Assistant Director for Special Education; the teachers, both in terms to their training (Mjaavatn, Frostad and Pijl, 2015) and their views (Mamas, 2013); the carers (paraprofessionals) of pupils identified as having SEN (Angelides, Constantinou and Leigh, 2009); and, of course, pupils without SEN (Szumski, Smogorzewska, Karwowski, 2017). Each one of these obstacles is divided into other individual obstacles which, given due effort by the school principal, could contribute to the creation of inclusive environments.

Specifically, according to Symeonidou (2018) teacher inclusive education in Cyprus is deficient. This may lead to negative teachers’ views towards the inclusion of pupils identified as having SEN, which promote marginalization (Mamas, 2013). Those views affect pupils’ views who underestimate their peers who are identified as having SEN (Pinto, Baines and Bakopoulou, 2019). Marginalization is increased by the lack of specialists such as speech therapists, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists (Phtiaka, 2006).

Furthermore, school principals face two additional problems: the leadership model they intend to apply and the way the legislation is implemented (Michaelidou and Angelides, 2009), which requires close cooperation between the school principals and the Ministry of Education and Culture, since they are responsible for implementing the law (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2020). Based on the above discussion we conclude that the Cypriot educational system is centralized (Damianidou and Phtiaka, 2017).

The above obstacles could, at least partially, be lifted through the decentralisation of authority, which would lead to the delegation of more responsibilities to school principals. As pointed out by Kontis, Moutopoulos, and Konti (2014), the ability of the school and also the school principal, to make decisions pertaining to the content of education (purposes, timetables and syllabuses, textbooks etc.) and to personnel matters (hirings, layoffs, incentives, promotions etc.), is minimal, since all decisions are taken on the central authority level and are subsequently passed down to the educational units in order to be implemented (Kassidis, 2015). Decentralising authority is a time-consuming process. Therefore, in this study we are proposing, at least partial, decentralisation of authority in the context of the Cypriot education system. This could be achieved through the creation of an inclusive leadership model (Papademetriou and Charalampous, 2018).

Intermediate Inverted Leadership (IIL) model

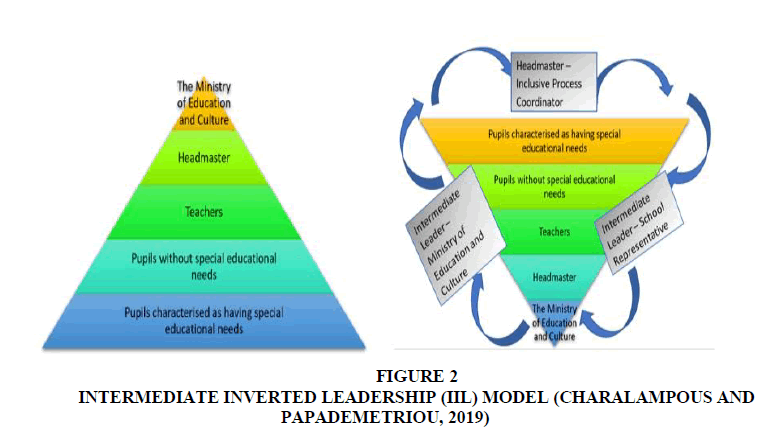

IIL model is an inclusive leadership model which that we have created in the context of our previous research (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2019). IIL model aimed at identifying the factors opposing the creation of an inclusive school environment and, subsequently, at the provision of guidance to them by the intermediate leaders (external intermediate leader: representative of the Ministry of Education and Culture; internal intermediate leader: representative of the school under research), in order to make them conducive to promoting inclusion (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2019) (Figure 2).

After fully applying the IIL model (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2019), through the Mixed Methodology Action Research (MMAR) (Ivanova, 2015), we concluded that this model can be instrumental in the creation of inclusive environments. That said, it also showed weaknesses. Particularly, as we mentioned in our previous attempt to apply IIL model (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2019), we realised that this computerized model has been applied to a single school. So, the conclusions of the implementation of IIL model (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2019) were too much dependent on a unique experimental setting to advocate evidences to supporting sustainability. Furthermore, another limitation was the presence of teachers as researchers, which may has increased the subjectivity of the results as they acted both as participants and as researchers. As a result, the participants might had tried to provide favourable answers after the implementation and the evaluation of the model. Thus, we recommended further research aiming to re-evaluating the implementation of this model in another school with different participants, both pupils and educators.

Emotional intelligence

Moreover, such an effort could be further enhanced if the school principal use emotional intelligence as a key driver. Emotional intelligence is defined by Mayer, Caruso and Salovey (1999) as one of its many potentials, corresponding to other types of intelligence. Bar-On (2000) interprets the term as a combination of social and emotional abilities, adaptation skills and personality traits. Goleman (1998) views it as a key parameter for interpreting and predicting performance in any field of occupation.

According to Aldiabat (2019) emotional intelligence is an important factor in guiding a successful leader, as it includes the following elements: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness and relationship management. In their research, Doe, Ndinguri, and Phipps (2015) point out that the key feature of a successful leader is emotional intelligence, i.e. the ability to exercise self-regulation and understand other people’s feelings, using empathy as a mean for effective management.

Methodology

The aim of this research was to retest the Intermediate Inverted Leadership (IIL) model, which we had conceived and tried to apply in a secondary education school in Cyprus, during the school year 2017-2018 (Charalampous and Papademetriou, 2018). The research procedure was based on Mixed Methodology Action Research (MMAR), suggested by Ivanova (2015). (MMAR). MMAR combines mixed methodology with action research and allows reflection and change of practices used in a school by the teachers themselves.

We believed we ought to tackle IIL model’s weaknesses, making a second attempt to apply the model in a different secondary education school, a fact that enabled us to ascertain whether the results from the implementation of the model are differentiated depending on the participants and the existing school culture.

The research questions of our first research were the following:

-What are the obstacles which hinder the efforts towards the inclusion of pupils characterized as having SEN?

-How can a leader transform the obstacles into tools which can enforce his effort towards the creation of an inclusive environment?

We found out that the main obstacles to the creation of an inclusive school culture were the Ministry of Education and Culture, the school principal, the teachers, the carers of pupils identified as having SEN and the pupils without SEN. Through the research process we concluded that each obstacle could also serve as a solution.

Thus, as part of our second attempt to apply the IIL model, we tried to answer the following research questions:

-Which were the major shortcomings of the IIL model?

-How can these shortcomings be minimised, thus managing to stabilise the inclusive culture?

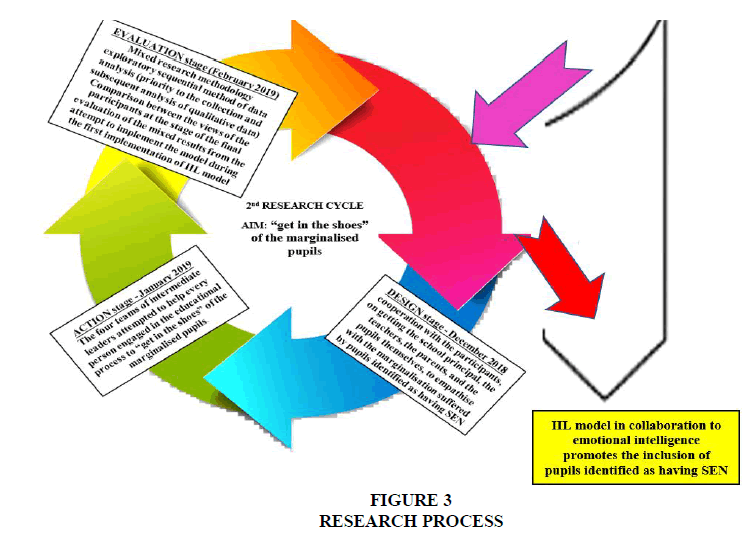

In our attempt to retest the model and answer the above questions, we once again employed the MMAR, while at the same time, enables the reconsideration and change of practices employed by the teachers themselves in the school under review. The research was conducted in a secondary education school of Cyprus and its total duration was ten months, from May 2018 to February 2019 (during two consecutive school years, 2017-18 and 2018-19). Participants included 48 teachers. Among them were the school’s principal, 5 assistant principals, 12 Greek language and history teachers, 8 mathematicians, 4 English language teachers, 3 physics teachers, 2 gymnastics teachers, 2 French language teachers, 2 technology teachers, 2 chemistry teachers, 2 biology teachers, 2 religion teachers, 2 computer teachers and 2 art teachers. 9 teachers-participants had 1-5 years teaching experience, 10 of them had 6-10 years of teaching experience, 11 had 11-15 years of teaching experience, 8 had 16-20 years of teaching experience and 10 had 21-25 years of teaching experience. In addition to the above, 4 parents of pupils identified as having SEN, 20 parents of pupils without special needs, 1 Special Education Connection Officer, 3 carers of children identified as having SEN and 80 pupils, participated in the research. The research tools included a user given questionnaire, interviews, observations during teacher lessons, breaks and meetings of the teaching staff, focus groups, and the researchers’ calendar. Teachers and parents participated in completing the questionnaire, in interviews, in focus groups and in observations. Pupils participated in interviews and observations. This specific MMAR comprises the following key stages: “Diagnosis”, “Identification”, “Design”, “Action”, “Evaluation”, and “Guidance”. It is worth noting that the completion of the first research cycle was followed by a second cycle, which went through the same stages.

Data collection and analysis, especially at the Design and Evaluation stages, were based on the exploratory sequential method proposed by Creswell (2014), which gives priority to the collection and subsequent analysis of qualitative data (interviews, observations, and journal), thus revealing the existing situation as regards the application of the inclusive theory in the said school. We then turned to the collection and, subsequently, the analysis of quantitative data (questionnaire), to explore the same parameter.

The questionnaire consists of three parts: Part A: Demographics, Part B: Obstacles in creating an inclusive culture, and Part C: School Principal’s role in including pupils identified as having SEN. The closed-ended questions included in Part A and Part B of the questionnaire were based on five-point Likert-type answers, which offered the choice of the following possible answers: 1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: Neither Disagree / Disagree, 4: Agree, 5: Absolutely Agree.

Participants were informed about the content of the research for approximately 10 minutes. Interviews lasted approximately 10 minutes, focus groups approximately 20 minutes, and observations approximately 40 minutes. Individual interviews and focus groups were conducted in the offices of Assistant Principals in the morning, while observations were held during morning hours, in classrooms and in the school yard. Data were collected using sound recordings and ground notes. Data analysis has been sent to the participants' personal e-mails, aiming in agreeing or disagreeing with them, thus attempting to confirm that the results were not biased. Qualitative data reflected impressions, the environment, verbal and non-verbal behaviours. All the above procedures prove in our view the validity and reliability of the research.

Regarding research ethics issues, all participants were asked, if they agree to the basic terms of this research effort, giving their consent to participate by signing the “Consent Form for Research Participation”. Participants were told that they could withdraw their consent at any time during the research, without consequences. The principal has also been granted permission to conduct the research. In addition, we reaffirmed the participants that we will respect the principles of confidentiality and anonymity throughout the investigation. Finally, it is worth noting that aliases were used in the data analysis stage.

At this point, it is worth noting that both the questions of the qualitative part, and the questionnaire used in this research, were identical to those used in the previous attempt to apply the IIL model. Figure 3 shows the whole research process.

Results

The results of the first attempt to apply the IIL model demonstrated that it can lead one step closer to the inclusion of pupils identified as having SEN. Nevertheless, the model had many weaknesses, which, if effectively dealt with, then, according to the participants in the research by Charalampous and Papademetriou (2019), the model might be improved over time.

At the same time this research was launched and, more specifically, during the “Diagnosis” stage (early May 2018) and through the analysis of interviews, observations, as well as the personal journals kept by researchers, members of the faculty noticed that certain pupils identified as having SEN were still being marginalised, despite the intense efforts of their teachers, and the school community at large, to ensure their inclusion.

Due to this specific reason, the focus of our research shifted towards the need for further exploring the issue, thus leading us to the “Identification” stage (end of May 2018), during which we employed the mixed research methodology.

The participants/co-researchers were initially very sceptical towards the effort to apply this innovative model. First, the school principal expressed the insecurity he was feeling regarding the potential impact of the model’s application, on the way he was leading the school.

During the data collection process, important conclusions were drawn regarding the identification of obstacles that a principal might encounter in his attempt to create an inclusive school environment.

Specifically, participants reported the following:

“I believe that a major obstacle to inclusion education is the existing legislation of special education system, which deprives the principal of the right to help pupils with disabilities. This does not mean that there are no pupils who are against the inclusion of children with disabilities” (Anna, teacher).

In addition, Maria, a mother of a child identified as having SEN, pointed out:

“There are very few periods during which children with disabilities are allowed to enter the mainstream class and that depends neither on us, nor on the teachers, nor on the headmaster”.

A total of 69 out of 72 questionnaires were fully completed by pupils. Regarding the biographical information 54.8% of the participants in the research were men and 45.2% were women. While analyzing the questionnaire results, it appeared that the policy of inclusive philosophy does not apply to school. It was revealed that the view that “Pupils with disabilities enjoy the same rights as other pupils in the school”, because “special education legislation is” not “inclusive”, since the two views have a statistically significant correlation based on the Pearson coefficient analysis (r=-.344, p-value =.001), “Teachers believe that pupils with disabilities are part of the school” (r=.281, p-value =.000). “Pupils hang out with classmates with special needs” At the same time, participants believe that there is no “money for the principal to properly apply inclusion” (r=.105, p-value=.000).

Additionally, as the results on the view that “teachers use inclusive teaching practices”, are high so is the statement that “curricula that guide teachers in teaching pupils do not take into account the difficulties of special needs pupils” (r=-.239, p-value=.031) (negative correlation as the percentages of one view increases the percentages of the other).

The “Identification” process was completed through the combination and interpretation of the qualitative and quantitative data, demonstrating that, in this specific school, pupils identified as having SEN were indeed being marginalised.

More specifically, the obstacles in promoting inclusion in this specific school were mostly related to the Ministry of Education and Culture and its centralist operation, for example: the institutional framework that governs special education in Cyprus; the constraints imposed by syllabuses in terms of teaching periods and teaching subjects; and the limited jurisdiction of the school principal. Therefore, by observing the above facts we realised that the main obstacle to the provision of inclusive education does not, after all, lie with the school principal or the teaching staff, but with the predetermined policies of the Ministry of Education, which do not allow the teachers, the pupils or the school community at large, to step up their inclusion efforts. Delving deep into the data, the authors recommended to the participants to apply the IIL model.

Utilising the mixed data, we proceeded to the “Design” stage (September 2018). Through analysis of the data collected during the diagnosis phase we concluded that a major obstacle in the process of applying inclusion was the issues related to the Ministry of Education. That’s why we tried to transform the issues related to the Ministry, from obstacles to supporters of the principal in his inclusive effort. So, creating a first action research cycle, we focused on the effort to raise awareness among Ministry of Education officials, mainly through an attempt to generate empathy, a key pillar of emotional intelligence theory. The Special Education Connection Officer was instrumental in the implementation of this effort. This person is a teacher who is relieved of his/her teaching duties for some teaching periods to regulate the relations between parents, teachers and pupils identified as having SEN. The purpose of this employee is to prevent any kind of marginalization of a pupil identified as having SEN.

The “Design” stage was followed by the “Action” stage (October 2018), during which the school principal, employing the emotional intelligence philosophy and always in cooperation with the two intermediate leaders, tried to raise awareness among Ministry of Education officials on the concept of inclusion. Thus, the research team prepared letters pertaining to the difficulties faced by school principals as part of the effort of their school to effectively include all pupils, with the aim of getting Ministry officials to empathise with the difficulties, views, and feelings of teachers, parents, and pupils, as regards their effort to effectively include pupils experiencing marginalisation. In addition, the school principal and the two intermediate leaders mobilised teaching unions, as well as Parent Associations, which, in turn, demanded from the Ministry to take measures for ensuring that pupils identified as having SEN are present in the mainstream classroom throughout the entire school day, and are efficiently included in the teaching process.

Upon completion of the 1st MMAR Cycle we moved towards the “Evaluation” stage (November 2018), during which the qualitative analysis of the interviews and the observations showed that the objective set had not yet been achieved. Indicatively we list the views that emerged through the establishment of a focus group. According to the school principal:

“I believe that, our idea and our attempt to affect the employees of the Ministry of Education views’ were great. But it did not have the expected results”.

According to the Special Education Connection Officer:

“Our effort has failed because by addressing the Μinistry we are not only addressing people who may be affected by the emotional side of the issue. These individuals are an organized entity that operates based on laws, financial resources and in general many factors that influence either its decisions positively or negatively”.

Τhe chairman of the school’s Parent Association pointed out:

“It would be extremely difficult to change his attitude towards the way children with disabilities are educated in such a short time”.

Finally, one of the two intermediate leaders noted:

“It is very difficult for the principal and the two intermediate leaders to influence effectively the policy pursued by the Ministry. The effort for change must be made by the school itself and then involve the ministry”.

Studying the above, we conclude that the idea of asking the Μinistry to tackle the issue from its emotional side was astonishing. Unfortunately, however, it was not effective. Despite the fact that both Ministry of Education officials and the local community acknowledged the need to implement inclusion practice and had already engaged in a dialogue aimed at creating the necessary conditions for its practical application, this effort was apparently very demanding and time-consuming, and it was extremely difficult to effect such a change overnight.

Therefore, we considered it necessary to proceed to a 2nd MMAR Cycle. The aim of the 2nd Cycle was the effective emotional intelligence guidance to create a more inclusive school environment. During the “Design” stage (December 2018) of the 2nd Cycle we focused, in cooperation with the participants, on getting the school principal, the teachers, the parents, and the pupils themselves, to empathise with the marginalisation suffered by pupils identified as having SEN.

The research process moved on to the “Action” stage (January, 2019) of a second research cycle, during which it was ascertained that the task of the two intermediate leaders entrusted with guiding the implementation of the IIL model, was extremely difficult because as one mother said:

“It is difficult for the two intermediate leaders to be informed about all the problems that the principal faces while trying to promote inclusion. We could also ask for help from other factors such as parents. We, as parents, could help the principal to drive pupils closer to inclusion”.

As a result of this, two extra teams of intermediate leaders were added: a team consisting of two parents of pupils without SEN and two parents of pupils identified as having SEN, and a team consisting of two pupils without special educational needs and two pupils with less severe SEN. These two new teams of intermediate leaders, in cooperation with the two aforementioned intermediate leaders (internal and external), undertook the task of guiding the entire school community towards the establishment of a lasting inclusive culture.

The four teams of intermediate leaders attempted to help every person engaged in the educational process to “get in the shoes” of the marginalised pupils. This was, of course, extremely difficult. Nevertheless, intermediate leaders have tried to achieve their goal to the extent that this was possible. The following actions were organised with the purpose of generating empathy.

Express experiences, feelings, views preventing marginalisation

Formation of separate teams of adults and minor, which met voluntarily during the afternoons in order to express their experiences, feelings, as well as views as regards the process of preventing marginalisation and, consequently, the process of inclusion. These meetings were conducted by the intermediate leaders, who tried to gradually instil the key principles of emotional intelligence into the participants: self-awareness (recognising their own feelings), self-regulation, empathy (getting into other people’s shoes), and motivation. The first group consisted of pupils without special needs. The aim of this group was to bring their emotions out of the inclusive process and to highlight the difficulties they had encountered in trying to apply the basic steps of empathy. The second group consisted of teachers and parents who analysed their thoughts and emotions during the process.

But let's look at some of the participants' thoughts:

“We learned, through the discussion, to understand first what exactly we feel about ourselves and then to understand of how others feel. We got to know our emotions, we came into conflict with ourselves, and then we improved our relationships with others and the way we treat them” (Anna, mother of a pupil without SEN).

“It is very hard to be on the sidelines…I will try as much as I can to help my classmates in order to get included. Worth it. I will definitely feel better too!”(John, pupil).

At this point it is worth mentioning that their feelings were mainly focused on the concern that pupils identified as having SEN are not accepted by other pupils, teachers or parents. Fortunately, however, these emotions soon changed as their classmates vigorously attempted to engage their classmates identified as having SEN.

It seems that the externalization of emotions, thoughts and the analysis of attitudes towards pupils classified as having SEN contributes to their identification through the analysis of research results. As a consequence, participants are one step closer to preventing pupils classified as having SEN from being oppressed. This perspective finds us in agreement with Baines, Blatchford and Webster (2015).

Enhancement of the self-esteem of all pupils

Enhancement of the self-esteem of all pupils, with or without SEN, through common activities were designed to prevent them from classifying themselves or other persons as superior or inferior. More specifically, the pupils were called to participate in events such as theatrical performances, dancing, and singing, thus accepting all differences. The purpose of these efforts was to make the participants feel social and emotional wellness, so that they feel that everyone deserves the same rights even though everyone is different.

At this point it is worth considering the following observation. Οne of the four intermediate leaders narrates:

“Most of the kids were reluctant to attend the Christmas school celebration. So, Eleni, the teacher thought that she could work with the pupils in the Special Unit, since she also taught them the Greek lesson. So, she asked in general: “Does anyone want to read a poem at an event?” Eight out of nine children said that they didn’t. Costa's view was typical: “No, no... other pupils will see us and laugh” Andreas, however, listened to her proposal with interest. Without losing his chance he offered to take over the recitation of the poem. Immediately, his expression changed. From that day he was smiling. Every day he was meting the teacher without asking her, in order to read his poem to her. The results were amazing. It is important to mention that at the beginning of the event, both teachers and pupils were looking at Andrea with pity. But when the poem was over, the applause he received was too much. Andrea's face really shone. The pupils and his teachers were impressed”.

According to one pupil:

“It was a life lesson for us. We understood how our classmate was feeling and realized how much psychic power a disabled child needed”.

We conclude that improving the self-esteem of pupils classified as having SEN leads to their inclusion by analyzing the research data (Pinto, Baines and Bakopoulou, 2019), since other students consider their skills in this way. The marginalizing tendencies are therefore ignored.

Mentor-pupils

Creation of the institution of mentor-pupils, i.e. pupils without SEN, who made sure to discuss with pupils identified as having SEN, to find out ways of achieving the more effective inclusion of these pupils. The proposed practices were recorded and evaluated, for their effectiveness to be assessed by the intermediate leaders.

Mrs Georgia, a career of pupils identified as having SEN narrates the following:

“Today, I saw something that made me very happy. One pupils who voluntarily asked to participate in the research by taking on the role of the mentor, approached two Special Unit pupils and managed to help them in order to join him into his company. At first it seems that his effort was quite difficult. One of those pupils had brain paralysis, while the other had autism. Every day the pupil-mentor tried even more to help those pupils, but things were still hard. One of them was telling him to leave, the other one was turning his back...Eventually, it seems that he was getting used to it. Two weeks later those pupils started watching videos on their mobile phones, chatting and smiling. A week after the results were much better. The pupil-mentor, along with five boys, approached the two Special Unit pupils, with which they became friends too. By the end, all of them were walking and playing in the yard of the school as a group”.

The foregoing observation is a shining example, demonstrating that through pupil mentoring pupils with and without special educational needs can coexist, collaborate, train without feeling that there are pupils who need to be marginalized because of their needs. Completing the effort to give some pupils the role of the mentor for pupils identified as having SEN, the mentor-pupils came up with some basic principles for building mentor relationships. These principles were:

“We listen carefully to the point of view of the others”

“Creating a relationship of trust”

“We believe that inclusion is possible for everyone”

“Strengthening self-esteem”

“Respect for everyone's personal data”

“We accept change for the better”

“We consider the personality of the mentor and the mentee, since each of us is different”

“We can get into the other's place (empathy)”

“Dialogue”

Adornment of school premises with inclusive messages

Finally, adornment of school premises with inclusive messages, by a team of pupils identified as having SEN. An example was the decoration of the stairs of the school by pupils with and without SEN, who inscribed each step, from the bottom up, with the following words in ascending order: Acceptance - Respect - Empathy- Cooperation - Friendship - School for all. Through this action, the participants sought to complete the present research by attempting to help pupils, teachers and parents make the theory of inclusion a part of their lives. By daily reminding the key steps of empathy, we tried to move one step closer to inclusion.

Moving to the stage of the final “Evaluation” stage (February 2019) that follows the 2nd Action Research Cycle, further interviews were conducted and observations were made, and the participants were handed the same questionnaire they had filled in at the “Diagnosis” stage, which took place prior to the commencement of the 1st Action Research Cycle. Data collection and analysis were based on the mixed research methodology that was guided by Creswell’s (2014) exploratory sequential method. Some of the participants' views on trying to revise the IIL model are illustrative. The school principal mentioned:

“I think the IIL model worked better now. The involvement of four than two intermediate leaders in the effort to promote inclusion has greatly enhanced it”.

Mr. Marios, a teacher said:

“The help that empathy provided us was yet another ally in overcoming the obstacles a manager faces in trying to be included”.

According to a pupil:

“Now I think our school is more democratic. We have changed behavior I think...We've learned to respect others and recognize that each of us has his/her strengths and weaknesses”.

The above statements regarding the success of IIL model beyond the qualitative data was confirmed by the data derived from the questionnaire analysis. The questionnaire was completed by teachers and parents during the present stage of the research was the same as the questionnaire completed at the stage of “Identification” of the first cycle of research.

Mixed data analysis showed that the IIL model was significantly enhanced, and this time (as compared to the attempt to implement the model during the previous school year in another Secondary Education school) it was based on more solid foundations for creating a sustainable inclusive culture. In order to gauge the extent of the improvement due to the re-application of the leadership model, we made a comparison between the views of the participants at the stage of the final evaluation of the mixed results from the attempt to implement the model during the first implementation of IIL model (school year 2017-2018) and the second implementation of IIL model (school-year 2018-2019).

Regarding the statement that the principal “Creates a shared inclusive vision for improving and developing the school in collaboration with staff” we conclude that there are modifications. Comparing the participants' views concerning this statement after the first and after the second application of the model, it appears that the above view becomes more intense during the second application of the model (Table 1).

| Table 1 Shared Inclusive Vision | ||

| Statement | 1st implementation of IIL model | 2nd implementation of IIL model |

| "Students with disabilities face a variety of difficulties and thus cannot benefit from regular school activities" | r=.002, p-value =.135 |

r=.014, p-value =-.271 |

| "Acceptance of pupils with their own abilities without particularities" | r=.000, p-value=-.231 |

r=.000, p-value=-.538 |

| "Difficulty in teachers 'collaboration with pupils with disabilities who do not have sufficient self-service skills" | r =.000, p-value=.021 |

r =.001, p-value=-.347 |

| “Ability of pupils with disabilities to understand pupils' emotions" | r =.003, p-value =-.111 |

r =.008, p-value =.294 |

Analyzing the qualitative data that emerged in the evaluation at the first application of the IIL model and comparing them with the data obtained at the second implementation of the model, we conclude that there were significant differences. Through the analysis, it emerges that participants' views on the role of the principal in trying to apply the theory of inclusion appear to be more positive in the second attempt to apply the IIL model.

Discussion

A critical factor for triggering any feature of the IIL model is the production of emotional intelligence and, in particular, empathy. The two intermediate leaders could direct the participants' thoughts and feelings through emotional intelligence to the successful implementation of the IIL model and, ultimately, to the effective inclusion of pupils classified as having SEN.

The school principal and the intermediate leaders had the following general features: Firstly, they attended to gain the confidence of teachers, pupils, and parents, by demonstrating to them in practice that they are aware of, and understand, their feelings. Secondly, they tried to establish the feeling that their personal aspirations and goals are aligned with the aspirations and goals of the wider team to which they belong. Another important research achievement was the iinvolvement of all team members in the achievement of the goals. Finally, their behaviour set an example for the other participants, who, by also acting as leaders in their interpersonal relationships with the pupils, were required to show empathy.

The participants to the MMAR initially considered the effort to apply the IIL model to be pointless, saying that intensive action for promoting inclusion is being taken for several years, without any significant results. Up to the completion of the 1st Action Research Cycle the participants considered the process to be another pointless effort, which confronted the centralized educational system governing the operation of special education in Cyprus.

Then, however, their attitude towards the IIL model and its ability to promote inclusion changed, as they realised that they themselves could also bring about change, by employing emotional intelligence and the parameter of empathy.

Conclusions

The present research can offer a lot to the academic community as well as to the improvement of education. We found that IIL model provides a further study concerning the relationship between educational leadership and emotional intelligence and the impact which their impact on promoting the inclusion of pupils identified as having SEN. Of course, the retest of the application of the IIL model and its enhancement through mobilising, and raising the awareness of, the representative of the Ministry of Education and the employment of emotional intelligence, does not imply that the model can be applied with total success in any school. In order to be able to be more specific regarding the results of a wider application of the model, we could further test it by applying it to as many schools as possible, and by enhancing it with any element that might possibly improve it. Finally, we could compare, based on both qualitative and quantitative data, the extent of its success in different schools, testing, at the same time, the factors that may account for such differentiation.

References

- Ainscow, M. (2005). Developing inclusive education systems: what are the levels for change. Journal of Educational Change, 6(2), 109-124.

- Ainscow, M., Booth, T. & Dyson, A. (2006a). Improving schools - Developing inclusion, Routledge.

- Aithal, P.S., & Aithal, S. (2015). An innovative education model to realize ideal education system. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 3(3), 2464-2469.

- Anastasiou, D., Kauffman, J., & Di Nuovo, S. (2015). Inclusive education in Italy: description and reflections on full inclusion. European Journal of Special Needs, 30(4), 1-15.

- Angelides, P., Constantinou, C., & Leigh, J. (2009). The role of paraprofessionals in developing inclusive education in Cyprus. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 24(1), 75-89.

- Aldiabat, B. (2019). The impact of emotional intelligence in the leadership styles from the employees point view in Jordanian Banks. International Business Management, 13(1), 14-20.

- Bar-On, R. (2000). Emotional and social intelligence: Insights from the Emotional Quotient 98 Inventory. In R. Bar-On, & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.). The Handbook of Emotional Intelligence (pp. 363-388). San Francisco: John Willey & Sons, Inc.

- Baines, E., Blatchford, P., Webster, R. (2015). The challenges of implementing group work in primary school classrooms and including pupils with special educational needs. Education, 43(1), 15-29.

- Black, A., Bessudnov, A., Liu, Y., & Norwich, B. (2019). Academisation of Schools in England and Placements of Pupils with Special Educational Needs: An Analysis of Trends, 2011–2017. Frontiers in Education, 4(3), 1-14.

- Blackburn, C. (2016). Early childhood inclusion in the United Kingdom. Infants & Young Children, 29(3), 239-246.

- Buli-Holmberg, J., Nilsen, S., & Skogen, K. (2019). Inclusion for pupils with special educational needs in individualistic and collaborative school cultures. International Journal of Special Education, 34 (1), 68-82.

- Garrote, A., Sermier Dessemontet, R., Moser Opitz, E (2017) Facilitating the social participation of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools: A review of school-based interventions. Educational Research Review, 20, 12-23.

- Celoria, D. (2016). The Preparation of Inclusive Social Justice Education Leaders. Educational Leadership and Administration. Teaching and Program Development, 27, 199-219.

- Charalampous, C., & Papademetriou, C. (2018). Inclusion or Exclusion? The Role of Special Tutoring and Education District Committees in Special Secondary Education Units in Cyprus. International Journal of Education and Applied Research, 8(1), 30-36.

- Charalampous, C., & Papademetriou, C. (2019). Intermediate Inverted Leadership: The inclusive leader’s model, International Journal of Leadership in Education.

- Charalampous, C., & Papademetriou, C. (2020). Intermediate Inclusive leader. Creating cooperation networks. 16th European Conference on Management Leadership and Governance, 26-27 October, Oxford UK.

- Chaudhry, A., & Javed, H. (2012). Impact of Transactional and Laissez Faire Leadership Style on Motivation. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(7), 258-264.

- Clinton, D. (2013). Quality Special Education Programs: The Role of Transformational Leadership. ProQuest LLC, Ph.D. Dissertation: Capella University.

- Damianidou, E., & Phtiaka, H. (2016). Transition from Exclusive to Inclusive Attitude and Teaching Practice: a Reality or a Vision? Education and Transition Conference. European Educational research association.

- Doe, R., Ndinguri, E., & Phipps, S. (2015). Emotional intelligence: The link to success and failure of leadership, Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 19(3), 105-114.

- EADSNE. (2007). Lisbon Declaration. Available online: https://www.european- -agency.org/country-information/cyprus/national-overview/special-needs-education-within-the-education-system.

- European Commission. (2018). Education and training monitor 2018 Greece. European Union Luxemburg.

- Goleman, D. (1998). Working with emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Dell.

- Hamburg, I., & Bucksch, S. (2017). Inclusive Education and Digital Social innovation. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 4(5), 162-169.

- Holmberg, J., & Jeyaprathaban, S. (2016). Effective practice in inclusive and special needs education. International Journal of Special Education, 31(1), 119-134.

- Hornby, G. (2017). Inclusive Special Education: development of a new theory for the education of children with special education needs and disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 42(3), 235-25.

- Ivankova, N. (2015). Mixed Methods Applications in Action Research. United Kingdom: Sagepub.

- Jahnukainen, Μ. (2015). Inclusion, integration, or what? A comparative study of the school principals’ perceptions of inclusive and special education in Finland and in Alberta, Canada. Disability & Society, 30(1), 59-72.

- Kasidis, D. (2015). The ability to educate children in the autism spectrum at general primary school. Disadvantages-Advantages-Challenges-Perspectives. Athens: Panhellenic Conference of Educational Sciences, 1, 1-10.

- Kontis, D., Moutopoulos S., & Konti E. (2014). The organization and administration of our education system is ultimately a brake or a lever in the development of the institution of the school today. pp1388-1392.

- Kurland, H. (2018). School leadership that leads to a climate of care. International Journal of Leadership in education.

- Linnan, H., & Li D. (2010). Exploration and Practice on Establishing the Mode of Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education for College Students. Research in Higher Education of Engineering.

- Mamas, C. (2013). Understanding inclusion in Cyprus. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 28(4), 480-493.

- Manzano-García, B., & Fernández, M.T. (2016). The inclusive education in Europe. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4(2), 383-391.

- Mayer, J.D., Caruso, D.R., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27(4), 267-298.

- Messiou, K. (2016). Research in the field of inclusive education: time for a rethink? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(12), 1-14.

- Michaelidou, A., & Angelides P. (2009). Investigation of the role of “special units” in the schools in Cyprus: a case study. In: Angelides, P. (Ed). Inclusive Education: From the margin to the inclusion. Limassol: Kiproepia, 87-106.

- Mjaavatn, P.E., Frostad, P., & Pijl, S.J. (2015) Measuring the causes for the growth in special needs education. A validation of a questionnaire with possible factors explaining the growing demand for special provisions in education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(4), 565-57.

- Oluremi, F. (2015). Inclusive Education Setting in Southwestern Nigeria: Myth or Reality? Universal Journal of Educational Research, 3(6), 368-374.

- Papademetriou, C., & Charalampous, C. (2018). Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Education: The model of the Inclusive Leader, 1st International Conference on Marketing and Entrepreneurship (ICME 2018), Neapolis University, Pafos, Cyprus.

- Petridou, E., & Glaveli, N. (2008). Rural women entrepreneurship within co-operatives: Training support. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 23(4), 262–277.

- Phtiaka, H. (2006). From separation to integration: Parental assessment of state intervention. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 16(3), 175–189.

- Pinto, C., Baines, E., & Bakopoulou, I. (2019). The peer relations of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream primary schools: The importance of meaningful contact and interaction with peers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 818-837.

- Priyanka, S., & Samia, K. (2018). Barriers to Inclusive Education for Children with Special Needs in Schools of Jammu. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 6(1), 93-10.

- Reinhartz, J., & Beach, D. (2004). Educational Leadership: Changing Schools, Changing Roles, Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Robinson, D. (2017) Effective inclusive teacher education for special educational needs and disabilities: Some more thoughts on the way forward. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 164-178.

- Rodriguez, C., & Garro-Gil, N. (2014). Inclusion and integration on Special Education. Science Direct Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences.

- Scanlon, G., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Shevlin, M., & McGuckin, C. (2020). Transition for pupils with special educational needs: Implications for Inclusion Policy and Practice. Transition for Pupils with Special Educational Needs: Implications for Inclusion Policy and Practice, 1-224.

- Soulis, S., Georgiou, A., Dimoula, K., & Rapti, D. (2016). Surveying inclusion in primary school students. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(7), 770-783.

- Symeonidou, S. (2015). Rights of People with Intellectual Disability in Cyprus: Policies and Practices Related to Greater Social and Educational Inclusion. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 12(2), 120-131.

- Symeonidou, S. (2018). Disability, the arts and the curriculum: Is there common ground? European Journal of Special Needs Education.

- Symeonidou, S., & Phtiaka, H. (2009). Using teachers’ prior knowledge, attitudes and beliefs to develop in-service teacher education courses for inclusion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 543-550.

- Strogilos, V. (2018). The value of differentiated instruction in the inclusion of students with special needs/disabilities in mainstream schools, SHS Web of Conferences 43, 0003.

- Strogilos V., & King-Sears, M. (2018). Co-teaching is extra help and fun: perspectives on co-teaching from middle school students and co-teachers. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 18(3), 148-158.

- Suleymanov, F. (2015). Issues of Inclusive: Some aspects to be considered. Electronic Journal of Inclusive Education, 3(4), 2-23.

- Szumski, G., Smogorzewska, J., & Karwowski, M. (2017). Academic achievement of students without special educational needs in inclusive classrooms: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 21, 33-54.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2005). EFA Global Monitoring Report: The quality imperative, Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Wanda, L. (2016). Principal preservice education for leadership in inclusive schools. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 17(1), 36-50.

- Wolfberg, P., LePage P., & Cook, E. (2009). Innovations in inclusive education: two teacher preparation programs at the San Francisco State University. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 5(2), 16-27.