Research Article: 2019 Vol: 18 Issue: 2

Turnover Culture and Crisis Management: Insights from Malaysian Hotel Industry

Maisoon Abo-Murad, AL-Balqa Applied University

Abdullah AL-Khrabsheh, AL-Balqa Applied University

Abstract

Living in a turbulent time brings crisis management as an essential approach for organizations survive, particularly those working for industries which are fragile and prone to a wide range of crises and disasters such as tourism and hotel industry. Organizational culture has a significant impact on crisis management practices, however, it remains underexplored territory that needs to be addressed and recognized. Hotel industry culture is described as burn out and turnover culture. The impact of hotels turnover culture has been studied heavily in different areas, while the impact of the turnover culture on crisis management still does not have the appropriate attention. The purpose of the current study was to understand the influences of turnover culture on crisis management practices in Malaysian hotels. The research was exploratory in nature and data was collected by carrying out in-depth interviews with 25 hoteliers, legislators, and government official who represent the Malaysian hotel industry. The open-ended responses were analyzed using NVivo 11 software for managing qualitative data and generating themes. The revealed findings were threefold: first, the Malaysian hotels are exposed to a wide range of crises with limited proactive crisis management. Second, the turnover culture in Malaysian hotels hinders the adoption of wide crisis management practices. Third, Malaysian hotels lack the awareness of the influence of turnover for managing crises. Based on these findings, the research offers the hotelier and legislator clear understanding of the detailed influence of the turnover culture on crisis management practices.

Keywords

Crisis Management, Organizational Culture, Turnover Culture, Hotel Industry, Malaysia.

Introduction

In the past dozen years, the world has witnessed a rapid growth in the number, complexity, and scope of crises. Some crises may have a significant effect on an organization’s property, workforce and business operations, while some others could threaten the whole existence of any organization (Coombs, 2014). Due to living in “turbulent and crisis-prone” world (Faulkner, 2001), the need for crisis management is crucial. It can make the difference between preventing crises and recovering well, or not at all. The traditional approach for managing crises that depends on reactive management style has approved its inability to handle crises. Proactive crisis preparedness is the soul of effective crisis management (Crandall et al., 2013). The main factor that determines whether the organization is crisis prepared or crisis-prone lies in its culture (Smith, 1990; Veil, 2011; Elliott & Smith, 2006). Organizational culture can either facilitate or constrain building the required capabilities for crisis management (Mitroff, 2005).

The harm and damage triggered by a crisis could seriously affect the financial resources in any country, especially for a country such as Malaysia where tourism plays an essential role in the local economy. Due to its economic significance, any crisis event within the tourism industry needs swift actions. Crisis management is the practices and means by which crises can be prevented or its impact can be minimized. Failure to manage crises may lead to financial and job losses, bankruptcy of investors, and at the most horrible scenario the breakdown and collapse of the tourism industry which may be the major contributor to the economy (Sausmarez, 2007).

Hotel industry benefits heavily from its human resources to attain its goals and competitive advantage (AbuKhalifeh et al., 2013; Ogbonna & Harris, 2002). The hotel industry is a high service business, where communication between staffs and guests define business success (Hemdi & Nasurdin, 2003). Despite that hotel industry depends highly on human factor for providing services; the turnover phenomenon is widely accepted (Iverson & Deery, 1997; Ogbonna & Harris, 2002). Interestingly, the hotel industry develops a turnover culture which is characterized by the “acceptance of turnover as part of the workgroup norm. That is, it is a normative belief held by employees that turnover behavior is quite appropriate” (Iverson & Deery, 1997). Turnover has been studied widely in different contexts; causes, consequences and remediation strategy of high turnover have been delivered from previous studies (Iverson & Deery, 1997; Ogbonna & Harris, 2002; Hemdi & Rahman, 2010). This study attempts to address the turnover culture in the context of crisis management, which has been overlooked by previous literature.

Problem Statement

Crisis management field is now more concerned than ever before about building organizational capabilities and skills, which in turn forms the ability and flexibility to confront uncertain, dynamic and complex situations (Robert & Lajtha, 2002; Lagadec & Topper, 2012). Besides, it is believed that the appropriate behavior and attitude for the human capital to build the required capabilities get its legitimacy from the prevailing culture (Mitroff, 2005). Organizational culture is at the core of proactive crisis management (Pauchant & Mitroff, 1992; Pearson & Clair, 1998; Elliott & Smith, 2006; Veil, 2011). Despite its importance; organizational culture influence on crisis management practices still insubstantial and not been fully addressed, (Veil, 2011; Bowers et al., 2017). Keeping with the wave; this research intends to participate in filling some gaps in this context.

Turnover is an endemic issue in the hospitality industry all over the world (Iverson & Deery, 1997; Deery & Shaw, 1999). It is even agreed in the literature to describe the hospitality culture as a turnover and burnout culture (Ogbonna & Harris, 2002; Hemdi & Rahman, 2010). The turnover rate in the hotel industry is estimated from 60% to 300% worldwide in comparison with manufacturing industry where the turnover rate is 34% (Walker & Miller, 2010). Likewise, in Malaysia, the Malaysian Employers Federation (2011) reported that the turnover rate in the hotel industry is 65.7% (Zainol et al., 2015). In Malaysia, turnover is not confined to the operational workers; it extends as well to the managerial levels (Zainol et al., 2015). Turnover in the Malaysian hotel industry is a serious problem owing to the heavy reliance of hotels on the human factor. Furthermore, the financial losses and moral impacts of turnover on hotels cannot be ignored (Hemdi & Rahman, 2010; Albattat & MatSom, 2013).

To recap, the research and knowledge about crisis management in Malaysia are still underexplored (Sausmarez, 2007; AlBattat & MatSom, 2014). Even those few Crisis studies that have been conducted in Malaysia, it has been devoted primarily to disaster and crisis response and recovery rather than crisis prevention and preparedness. Furthermore, it seems that there is still paucity in addressing the cultural aspects in the context of crisis management in Malaysia. So this would be a good opportunity to enrich the field of crisis management and fill the gap specifically that what has been written based on the conceptual and theoretical basis rather than empirical research.

Literature Review

Crisis Management

Basically, crisis management defined as a “systematic attempt by organizational members with external stakeholders to avert crises or to effectively manage those that do occur” (Pearson & Clair, 1998). The notion of crisis management recalls several imaginations in our minds. It may invoke the organizational activities that seek to prevent and face terrorist actions, rumors, sexual harassment, natural disaster, product recall, technology breakdown, and loss of information. “Indeed it is much broader than that” (Crandall et al., 2013). However, the crisis management field passed through several evolutions over the past few decades before it reaches this wide-ranging view. It is almost agreed in the literature that Tylenol (pain relief capsules product for Johnson & Johnson Company) poisoning with cyanide in 1982, cause the launch of modern crisis management (Burnett, 1998; Mitroff, 2005; Crandall et al., 2013) which signify the adoption of proactive initiatives, and taking more strategic, holistic and integrative view to crisis management. Remarkably, since that time the crisis management field has witnessed huge expansion, reflected by numerous models for crisis management and theories that have been introduced (Fink, 1986; Gonzalez-Herrero & Pratt, 1996; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993; Veil, 2011; Mitroff et al., 1988; Coombs, 2014). The main common elements of these models are covered by one umbrella; prevention, preparing, responding, and revising. Prevention and preparation functions are usually addressed before a crisis, responding function during the crisis event, while revising function after the crisis. Models then differ from each other upon the crisis definition perceived by a scholar, scholars’ discipline, and scholars’ perspectives.

Organizational Culture and Crisis Management

Culture has been related to organizational studies increasingly (Hofstede, 2010; Schein, 2006). Organizational culture is vital to the functioning of an organization, and it is believed that it has the potential to influence organizational activities (Veil, 2011; Mitroff, 2005; Hofstede, 2010; Schein, 2006). The context of culture signifies a socially constructed system of shared behaviors, values, and beliefs that are learned by the members of the organization (Schein, 2006). It is referring to the “glue” that binds people together within an organization in order to provide guidance, harmony and sense of direction. Furthermore, the number of researchers supports the view that the organizational culture is part of the organization rather than considering as something an organization possesses. Culture to an organization is as personality is to an individual (Mitroff et al., 1988).

Effective crisis management is all about crisis prepared organization (Pauchant & Mitroff, 1988; Smith, 1990; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993; Pearson & Clair, 1998). The main factor that determines whether the organization is crisis prepared or crisis-prone lies in its culture (Smith, 1990; Mitroff, 2005). It's almost taken for granted that the culture which we belong to influences our views to all aspects of our lives; indeed, culture governs our behaviours, attitudes and methods of communication even in difficult situations (Schraeder et al., 2005). The organization’s culture can impede or aid crisis management practices. There is a consensus among researchers that the culture of an organization can work to quick a crisis by providing the environment within which it can be escalated; on the other hand the culture can be the major factor that provides organization with the ability to prepare, respond, cope and learn in crisis (Fink, 1986; Smallman & Weir, 1999; Veil, 2011).

Some organizations deny their vulnerability to crises by using defensive mechanisms, and hence justify why they do not adopt crisis management. These mechanisms are rooted in their culture such as denial, idealization and disavowal (Mitroff, 2005). Even if the organization adopted a crisis management program, and proved the ability to prepare for crises, still, culture has a great influence on how it really faces crises. Ultimately crisis management is not a formal plan which consists of processes and procedures that should be applied exactly as it was envisioned; since no crisis ever occurs as planned (Mitroff et al., 1988). The organizational culture will be the governor at such difficult situations since attitudes and behaviors of employees are highly programmed by their culture. It does not matter how much crisis plan is elaborated if employees’ interactions and behaviors do not support the existing plan. Moreover, the organization’s culture determines how to learn from previous crises and how to enclose this learning in crisis planning (Veil, 2011).

In the event of crises, decision making based on accurate and timely information is central to success in minimizing losses and fast recovery. Open and flexible communication must be enhanced, so information passed throughout the organization quickly and directly to whom it may concern (Faustenhammer & Gössler, 2011). Mishra (1996) has highlighted the importance of trust for communication, gathering accurate information and decision making. However, it is believed that most organizations suffer from a contrary situation where less valuable information is passed through and in a slower manner. This communication distortion must be prevented in order to achieve effective crisis management (Smallman & Weir, 1999). Finally, after a crisis occurs, the emphasis is on resilience and learning from the previous crisis. Learning provides an organization with lessons and new knowledge to prevent such crises and to improve warning signal detection, damage containment and recovery mechanisms. However, the main organizational cultural barrier has been identified in the literature is “Blame culture”. Such organizational culture concerns in assigning the responsibility of errors to someone, rather than finding the root causes of error (Catino, 2008).

Turnover Culture in Hotel Industry

A bulk of studies has addressed the turnover problem in the hotel industry throughout the last dozens of years. The concern is continued to increase owing to the huge financial, operational and moral effects of turnover on hotel industry (Abelson, 1993; Deery & Shaw, 1997; Cheng & Brown, 1998; Iverson & Deery, 1997; Deery & Shaw, 1999; Ogbonna & Harris, 2002; Carbery et al., 2003; Yang, 2008; Davidson et al., 2010; AlBattat & MatSom, 2013; Zopiatis et al., 2014).

The hotel industry has a high level of temporary staffs, low wages, and low levels of training and high labor turnover (Deery & Iverson, 1996; Ogbonna & Harris, 2002; AlBattat & MatSom, 2013). Turnover causes have been studied extensively in the literature; Price & Mueller (1981) identified the repetitive work, social support, fair pay and rewards, promotional opportunity, training, and career development as the main factors for individuals to make the decision to leave the organization. Other significant factors have been added later as job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Deery & Iverson, 1996).

The consequences of high turnover are numerous and it could cost the hotel in several ways. The direct cost is the cost of recruitment, selection and training; While the indirect costs owing to the loss of productivity, performance and kill the organizational culture (Deery & Shaw, 1999; Ogbonna & Harris, 2002). However turnover costs are hard to calculate (Simons & Hinkin, 2001), it’s roughly estimated that the replacement of one worker cost at least 25% of the total annual compensation for the employee (Kenny, 2007). Losing the competitiveness of the organization in the long term is another penalty (Ismail & Lim, 2007). Besides, turnover may tarnish the organization’s image, decreases chances of improvement, slows down implementation of new programs, and declines productivity (Abbasi & Hollman, 2000).

There was a general consensus on the causes of turnover, but a consensual chasm exists regarding extent of influence, approach and the interactive impact in these causes. This has been reflected on the elusiveness of wide accepted models for turnover (Blau & Boal, 1989; Meyer et al., 2002; Jaros, 1997; Williams & Hazer, 1986; Mobley, 1977).

Reviewing the literature of turnover on hotel industry revealed two streams of studies. The first stream of studies has focused on insulating the causes of high turnover in the hotel industry and proposing strategies for retention. The second has drawn more attention to the organizational culture. They have considered turnover culture as a particular level of the organizational culture which in turn is responsible about employees’ turnover “where there is a normative belief among workers that relatively high turnover is quite acceptable” (Iverosn & Deery, 1997). In his research about turnover Abelson (1993) argued that there is a specific culture included in the organizational culture called turnover culture. Abelson has defined the turnover culture as “the systematic patterns of shared cognitions by organizational or subunit members that influence decisions regarding job movement”. Abelson argument has been supported by later researchers. For instance; Deery & Iverson (1996) and Deery & Shaw (1999) supported this argument on their researches. They confirmed the existence of turnover culture in the hotel industry, which is found to be the key contributing factor in an employee’s intention to leave.

Another significant aspect of turnover culture is that it is acting as a counter-culture to the organization’s objectives and values by producing negative consequences. Some of the consequences of the turnover culture are: low organizational commitment (Iverson & Deery 1997), lack of trust between employees and their management and among the employees themselves (Balkan et al., 2014), increased inaccurate communication behavior (Mueller & Price, 1989; Price, 1989), negative impact on knowledge, integration, innovation, productivity and performance within organization (Price, 1989).

Crisis Management in Hotel Industry

Undeniably, hotels have numerous features that make them exposed to wide types of threats and crises (Faulkner, 2001). The hotel industry is one of the main pillars of the tourism industry. Review of crises affecting the tourism industry, the hotel industry has received resemble effect. Those industries are characterized by interconnectedness and interdependence among different parties which makes them vulnerable to a wide variety of threats. Still, more fragility resulted also owing to relying on many other external sectors, such as transportation, banking and currency exchange rate, political situation, environment and weather (Pforr, 2009). Therefore, tourism is facing increasingly complex, serious and surprising crises (Faulkner, 2001; Ritchie, 2004). Moreover, the globalization of the tourism industry has opened the business to a wide set of global risks; exposing the operating organizations to economic, social, political and technological fluctuations. Besides, the impact of the tourism crisis is magnified due to the extreme media coverage; hence the ripples of the crisis can result in more subsequent problems (Blackman & Ritchie, 2008). More specifically, hotel industry seems to be a soft target for terrors, for instance, the terrorist attacks in Bali (2002), Amman (2005), Mumbai (2008) and Jakarta (2009) all happened in hotels. In their study, Then & Loosemore (2006) revealed that hotels facilities are the third most exposed buildings and targeted for a terrorist attack after the government buildings and iconic buildings. The hotel sector also endures massive losses from facing continual crises from epidemic outbreaks and economic and political turbulences which notably results in remarkable dwindling on the coming tourist arrivals (Wang & Ritchie, 2010).

The crisis management studies in tourism have increased dramatically in the past dozens of years (Wang & Ritchie, 2010). However, the research on tourism crisis management seems to be more focused on the response and recovery rather than prevention and preparation (Ritchie, 2008). Wang & Ritchie (2010) reviewed hotel crisis management studies have published in July 2009 in 37 journals; they found that 82% of the reviewed studies have addressed response strategies during a crisis. This reflects that the reactive crisis management approach is prevalent in the literature. Furthermore, on the same line Pforr (2009) argues that the literature on crisis studies in tourism and hospitality is disjointed and very fragmented which results on lack of clarity and knowledge about the causes, impact and strategies of crises. Also, the organizational culture aspect has been overlooked in hotel crisis management literature (Ritchie et al., 2004) which requires more research to understand the contributions of the organization culture to hotel crisis management practices. Ironically, the field is demanding more research about proactive crisis management with a more integrative and holistic view.

To conclude, the susceptibility of hotels to a wide variety of threats and crises stimulate the need for considering proactive crisis management approach. It is believed that deploying and initiating the proactive crisis management approach in the hotel industry will certainly improve the sustainability of the tourism industry which will be reflected positively on the whole economy. Bearing in mind these considerations besides taking the significant role of organizational culture, this research has three main objectives: Firstly; to shed the light on the crisis management in Malaysian hotels, secondly; to understand the turnover in Malaysian hotel industry, and thirdly; to explore the total influence of the turnover culture on crisis management in Malaysian hotels.

Methodology

The results of this study are based on face to face in-depth interviews conducted with hoteliers, legislators and key players in the Malaysian hotel industry. Purposeful sampling was used for selecting the participants. Basically, interviewees were approached both personally and through formal email where individual interview request has been sent. Later snowballing strategy has been applied in order to approach the most fitting personnel for the sake of this study. The sample consisted of 25 participants and conducted into two stages. In the first stage participants from hotels were approached. 17 participants were a mixture from different star rating hotels and working at different levels; three general managers, three human resource managers, two security managers, two front office managers and seven nonsupervisory staff. The hotels included two five-star hotels, one four-star, and one three-star hotels. In the second stage, the research extended to key outsider players from both government and hotel associations. The input of those participants was vital since they represent the regulated and authority arm in the hotel industry. Five participants from the ministry of tourism and culture and 3 participants from hotel associations, all working in management level and decision-making positions with decades of experience in the tourism and hotel industry. The variations in participants’ profiles enrich the revealed data.

Although all participants are from the Malaysian hotel industry, the interview questions have been deliberately formulated for each participant. Understanding the variances among participants in terms of their job description, management level, authority and crisis knowledge entails altered research interviews. For instance, the interview questions for operational staffs at hotels are much different from those directed to participants who are crisis experts. Notwithstanding the revealed data from each participant contributes to fulfilling the research objectives. Ironically the variances among participants’ profiles support understanding the turnover culture from different perspectives and hence more integrated approach.

Findings And Discussion

A Glance about Crisis Management in Malaysian Hotels

The first remark during the data collection was the limited awareness among hoteliers regarding crisis and crisis management in the hotel industry. Most participants from hotels failed to deliver the meaning of crisis management. When the participants were requested to address the main threats that may face Malaysian hotels, the finding revealed that the majority of participants emphasize the technical problems and threat like fire and natural disasters. Generally, the crises are varied from internal crises like power failure, technology breakdown and death of guests, to external crises like natural disasters which result in mass cancellations of booking. However, from another side, the participants from the government and hotel association show more awareness of crisis and crisis management. Indeed those participants have long experience in the industry and they can see the big view of the industry and consequently they can understand the actual impact of different crises on the hotel industry.

When the participants were asked to define crisis management, they described the technical procedures for hotel evacuation and fire fighting. It is obvious from their responses that the crisis management is a set of prescribed procedures-if it is available in the first place-that they adhered to in the situation of crisis. In Malaysian hotels, crisis management is still not considered as an independent activity; yet it is implemented as part of management activities. During the data collection, it was observed also that there is no specific unit for crisis management, while the functions and duties of crisis management are performed by other departments such as security department, loss prevention or even by human resource department.

One important theme has been found from the data is the heavy use of justifications and defensive mechanisms. The findings show that the participants tend to rely on several defensive mechanisms to justify their ignorance and unawareness of crises and crisis management. For instance, Despite the fact that hotels are one of the most facilities that most likely targeted by terrors (Then & Loosemore, 2006), the findings come with surprising results. None of the participants from hotels addressed terrorism as a threat to their business. They acknowledge the threat of the terrorism for other countries worldwide but when it comes to Malaysia they denied the probability of occurrence. Furthermore, other defensive mechanisms were used by participants as a rationalization to diminish the importance of crisis management such as: lack of resources, lack of regulations, and the belief that crisis management is someone’s responsibility “government” and crisis happened by fate, so nothing can be done in advance.

The findings in this section are strongly consistent with previous literature. Several studies have found that hoteliers have limited knowledge and education about crisis management which has been reflected on the confinement to reacting to the crisis once it happens (Ritchie et al., 2014; Wang & Ritchie, 2010; Pforr, 2009).

Insights about Turnover Crisis in Malaysian Hotels

The finding discloses that there is a lack of awareness among hotel managers regarding the turnover as well. The majority of participants accepted that the hotel industry has high turnover, but they denied accepting it as a crisis that affects their business. High turnover is a double side issue; on the first side, it’s a crisis in the hotel industry that should be taken into consideration and plan ahead for. From the other side, it develops more negative consequences in the organizational culture which lead to more barriers on crisis management practices. The half side will be discussed in depth on the next section.

The Malaysian hotel labor market is unstable and facing several challenges. The general manager of Malaysian hotel association stated on this regard that there are two challenges; the first is the difficulty to entice proper labour; while the second is that the Malaysian hotels have high levels of employee turnover which mean a substantial loss of human capital investment, training and quality.

Some comments from within hotels support this existence of the turnover problem. One HR manager in five-star hotel comments: “You know from 150 staff just100 of them will be with us for three months. This is the hotel industry. The staff always move around to get experience and more pay.”

Another front line worker comments: “They pay me peanuts but they expect me to give the best service to people, how come? You know this is the third hotel I work in; the longest working period was two year. Now I am looking for a better offer!”

Turnover Impact on Crisis Management

Digging a little deeper, high turnover which results in forming turnover culture can jeopardize the effort of crisis management practices. Ironically it can be a trigger for more crises. The finding of this study revealed some noteworthy points regarding the impact of turnover culture on the crisis management practices. Despite it is argued that these points are not mutually exclusive, it will be discussed separately for the sake of full understanding of the influence of the turnover culture on crisis management practices. Furthermore, those points are not exhaustive effects of the turnover culture, but rather those identified through this study.

Turnover Culture Builds Silent and Irresponsible Workforce

High turnover builds a sense of loss of direction, shared values and shared purpose among employees, these sentiments will be reflected on their daily routine activities and practices including crisis management practices. For example at the Pre-Crisis stage, the emphasis is on prevention and preparation activities. Signal detection is considered as the main component of crisis preparation. Early detection of warning signs enables the organization to avoid crises by proactively preparing and dealing with a potential crisis rather than responding and reacting to a full-blown crisis. Some of the signal detection systems that have been described in the literature include: surveys, audits, reviews, complaints, and more. The turnover culture encourages the hotel workers to disclose the bad news or signs owing to their feeling of disaffiliation to the organisation.

When asked about their ability to transmit bad news to management, the participants from operational levels declared that they don’t prefer to raise bad signs or messages to the management. Their justification shows that the turnover culture is behind this attitude.

“Sometimes I see negative behaviour from some staff with guest, but I never tell the management. Why should I get in troubles? You know this is the third hotel I worked for during the last five years. In all the hotels I worked for I just did my work” Front office executive in a five-star hotel.

“I never tried to tell the management about the negative comments from reviewers on the internet, I think they have their method to see the online review, and as a part-time worker no one asks me about such issues, honestly my concern is to finish my shift. That’s all” Chief at a three-star hotel.

While the organizational culture acts as a melting pot where all workforces engaged in a shared pattern of values, attitude, beliefs and behavior that govern how the organizational operate; the turnover culture acts as an opposing culture to the organizational culture. The abovementioned comments demonstrate that turnover builds a culture where the workforces feel disaffiliated from their organization. The disaffiliation feeling is the reason behind the tendency of hotel workforce of not raising to the management any bad news or issues that may escalate into a crisis.

Turnover Culture Hinder Healthy Communication among Workforce

For crisis management, it is necessary to have effective communication channels in the organization. Open and flexible communication is at the core for almost all crisis management practices at different stages. Short time, threat and the surprise elements of most crises imply that tough decisions need to be made quickly. The decision makers at this critical stage rely heavily on gathering related information in order to formulate the appropriate decisions. Repeatedly twoway communicating approach with different stakeholders is the best way of gathering information. When communication is exhaustive, timely and precise, decisions tend to be more effective. “Good or bad communication can still make or break a crisis” (Sapriel, 2003).

However, the findings revealed that the turnover culture is a devastating barrier for gathering information. The instability and the continuous change of the employees resulted by turnover affect the communication between staffs and different managerial levels. Due to the feeling of non-affiliation to their organisation; the employees are unwilling to share information and communicate properly which leads to distorting or wilful withholding information from their supervisor or blocking the flow of bad or unpleasant information. The security manager in fourstar hotel comments:

“During my work experience, I faced several incidents that need investigation. I noticed that the part-time and new employees are less cooperative in the investigation than the employees who stay with us for a long time. I think that those have the intention to leave soon so they don’t feel committed to the hotel, they are not truly engaged and involved properly”.

This finding is consistent with the previous literature. According to Price (1989); the turnover found to produce more transmitting information but on the other hand, the transmitted information is less accurate information (Price, 1989).

Turnover Culture build Mistrust Environment

Trust in the workplace brings up an atmosphere of innovation, loyalty, motivation and creativity. “Trust is one party's willingness to be vulnerable to another party based on the belief that the latter party is: 1) competent, 2) open, 3) concerned, and 4) reliable” (Mishra, 1996). On the contrary, turnover destroys trust among employees and builds a free trust environment, (Balkan et al., 2014). Based on this argument employees in such environment have been seen by their managers as incompetent and unreliable; while the managers are less open and don’t concern about the interest of their employees. The lack of trust between management and employees and among employees themselves destroys morale and loyalty.

Unfortunately, it seemed that hotels in Malaysia are not an exemption of this flaw. The findings show that top management at hotels distrusts their staff which results in decisionmaking centralization and rigid authority. One of the comments from the HR manager at a fivestar hotel supports this argument:

“Manager not only tells us what to do but even, how to do. As staff in this hotel, we are directed task by task. I don’t think the management trust their staff and able to give them autonomy, do you know why? This is because of turnover. It is ironic management cannot give autonomy and they know you may leave soon.”

Mistrust affects the crisis management practices in different ways (Mishra, 1996). Effective decision making during a crisis as mentioned previously, rely on accurate and precise information. While the trust is essential for the flow of information; mistrust results in losing synergetic among employees leading to shut down the communication channels both bottom up and top down. In this case, the information will be obstructed and distorted. Basically, the lack of trust limits full disclosure and withholds the required information.

Moreover, in the wake of the crisis, it is necessary to delegate decision making to others and having decentralization system which helps to respond efficiently. Delegation authority and decentralization means accepting dependence on other lower level staffs which is at the core of the trusting behaviour. Lacking trust on the contrary build more centralized decision-making system. This issue has been added by a front office manager.

“I prefer to report any accident with guests to the management, and they decide what the appropriate actions are. This is the safest way to avoid punishment”

The scapegoating and blame behaviour is another negative outcome of lacking trust in hotels which directly affect the crisis management practices. Rather than looking for the root causes of the problems that happened, the organisation is looking around for an individual to assign the responsibility. High turnover in hotels fosters such behaviour and make it dominant in their culture.

Turnover Culture Disrupt Training and Learning Activities

In hotel industry, the human capital considered as the main operator and service provider. The emphasis is on resilience and learning from previous crisis. Learning provides the organisation with lessons and new knowledge to prevent such crises, and to change and improve warning signal detection, damage containment and recovery mechanisms.

Turnover has a negative impact on the effectiveness of the learning process. Learning encompasses activities related to searching for crisis causes and changing of underlying redundant systems and training. For learning processes, the knowledge is acquired collaboratively. Training and retraining are essential for successful learning. High turnover impacts the effectiveness of training in the hotel industry, since it seems that managers are reluctant to spend more resources on staff training, and then they may leave after a while. In this regard one hotel manager comments.

“For me, I cannot expend money into training projects which will not benefit the hotel. We like to pay for training to staff that is likely to stay with us.”

Besides, that turnover enhances the blame culture and scapegoating behaviour as mentioned earlier which result in disruption of the learning process.

Digging deeper, the constant changing of employees affect negatively the organisational knowledge database especially the tacit knowledge. Continuous changing of employees means lower experience and background; hence staffs are less familiar with the organisations work conditions and the probable problems, regrettably resulting in repeated mistakes and incidents. The human resource manager at five-star hotel comments:

“I think that every process should be well documented to avoid repetitive questions and errors from the new staff, but unfortunately with all best efforts we did in this regards I do believe that we lose some of our knowledge with every single staff leave, still some knowledge cannot be documented”.

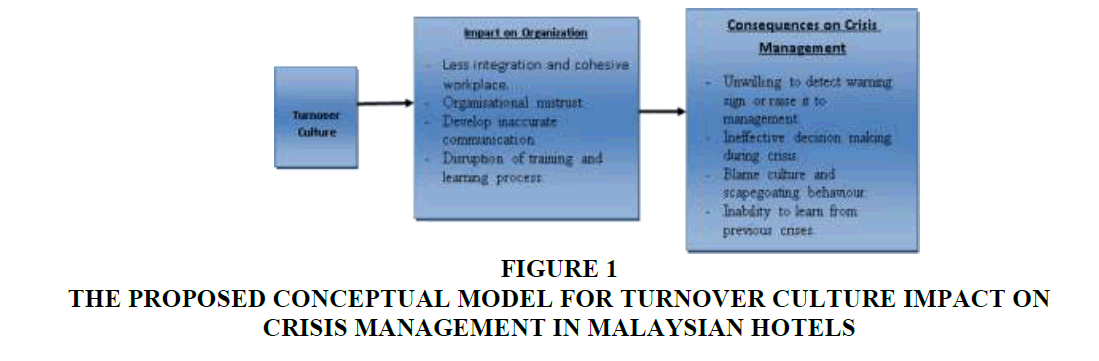

Proposed Conceptual Model

Based on the above-mentioned findings and arguments, the conceptual model of the impact of turnover culture on crisis management practices in the hotel industry can be proposed as depicted in Figure 1 next. The proposed model addresses some of the turnover culture influences on organisation and crisis management practices.

Figure 1.The Proposed Conceptual Model For Turnover Culture Impact On Crisis Management In Malaysian Hotels.

Conclusion

This research aims to develop a better understanding of the impact of turnover on crisis management practices in Malaysian hotels. The results revealed that Malaysia hotels face a wide range of crises including the high employee turnover. Drilling down the findings revealed that the employees’ turnover has a substantial impact on the crisis management practices. Those impacts have been presented. The turnover culture fosters negative outcomes that inhibit the crisis management practices. Turnover culture builds a silent and irresponsible workforce, mistrust environment which constrains the efforts of detecting looming crises and hinder the communication and sharing information at the wake of the crisis. Last but not the least, turnover disrupt the learning process and thwart training. This research is one of few that are considering crisis management in the Malaysian hotel industry and more specifically the impact of turnover culture on Malaysian hotels’ crisis management. Despite the limitation of the sample size of this study; the contribution of this paper is threefold. First, it adds to the crisis management knowledge in the hotel industry and service enterprises context. Second, it addresses the impact of turnover culture on crisis management practices. Third, it draws the attention of managers to the necessity of strategically manage the turnover to overcome the negative barriers and influences on crisis management practices. Future empirical studies are needed to incorporate and extend to other industrial contexts.

References

- Abbasi, S.M., & Hollman, K.W. (2000). Turnover: The real bottom line. Public Personnel Management, 29(3), 333-342.

- Abelson, M.A. (1993). Turnover cultures. Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management, 11(4), 339-376.

- AbuKhalifeh, A.N., Som, A.P.M., & AlBattat, A.R. (2013). Strategic human resource development in hospitality crisis management: A conceptual framework for food and beverage departments. International Journal of Business Administration, 4(1).

- Alan, S.Z.R., Radzi, S.M., Hemdi, M.A., & Othman, Z. (2008). An empirical assessment of hotel managers’ turnover intentions: The impact of organizational justice. In AFBE 2008 Conference Papers, 598-622.

- AlBattat, A.R., & MatSom, A.P. (2014). Emergency planning and disaster recovery in Malaysian hospitality industry.Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,144, 45-53.

- AlBattat, A.R., Som, A.P.M., & Helalat, A.S. (2013). Overcoming staff turnover in the hospitality industry using Mobley's model. International Journal of Learning and Development, 3(6), 64-71.

- AlBattat, A.R.S., & Som, A.P.M. (2013). Employee dissatisfaction and turnover crises in the Malaysian hospitality industry. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(5).

- Balkan, M.O., Serin, A.E., & Soran, S. (2014). The relationship between trust, turnover intentions and emotions: An application.European Scientific Journal, ESJ,10(2).

- Blackman, D., & Ritchie, B.W. (2008). Tourism crisis management and organizational learning: The role of reflection in developing effective DMO crisis strategies. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(2-4), 45-57.

- Blau, G., & Boal, K. (1989). Using job involvement and organizational commitment interactively to predict turnover.Journal of Management,15(1), 115-127.

- Bowers, M.R., Hall, J.R., & Srinivasan, M.M. (2017). Organizational culture and leadership style: The missing combination for selecting the right leader for effective crisis management. Business Horizons, 60(4), 551-563.

- Burnett, J.J. (1998). A strategic approach to managing crises.Public Relations Review,24(4), 475-488.

- Carbery, R., Garavan, T.N., O'Brien, F., & McDonnell, J. (2003). Predicting hotel managers' turnover cognitions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(7), 649-679.

- Catino, M. (2008). A review of literature: Individual blame vs. organizational function logics in accident analysis.Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management,16(1), 53-62.

- Cheng, A., & Brown, A. (1998). HRM strategies and labour turnover in the hotel industry: A comparative study of Australia and Singapore. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 9(1), 136-154.

- Coombs, W.T. (2014).Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding. Sage Publications.

- Crandall, W.R., Parnell, J.A., & Spillan, J.E. (2013).Crisis management: Leading in the new strategy landscape. Sage Publications.

- Davidson, M.C., Timo, N., & Wang, Y. (2010). How much does labor turnover cost? A case study of Australian four-and five-star hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(4), 451-466.

- De Sausmarez, N. (2007). Crisis management, tourism and sustainability: The role of indicators.Journal of Sustainable Tourism,15(6), 700-714.

- Deery, M.A., & Iverson, R.D. (1996). Enhancing productivity: Intervention strategies for employee turnover. Productivity Management in Hospitality and Tourism, 68-95.

- Deery, M.A., & Iverson, R.D. (1996). Enhancing productivity: Intervention strategies for employee turnover.Productivity Management in Hospitality and Tourism, 68-95.

- Deery, M.A., & Shaw, R.N. (1997). An exploratory analysis of turnover culture in the hotel industry in Australia. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 16(4), 375-392.

- Deery, M.A., & Shaw, R.N. (1999). An investigation of the relationship between employee turnover and organisational culture. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 23(4), 387-400.

- Elliott, D., & Smith, D. (2006). Cultural readjustment after crisis: Regulation and learning from crisis within the UK soccer industry.Journal of Management Studies,43(2), 289-317.

- Elliott, D., Harris, K., & Baron, S. (2005). Crisis management and services marketing. Journal of Services Marketing, 19(5), 336-345.

- Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management.Tourism Management,22(2), 135-147.

- Faustenhammer, A., & Gössler, M. (2011). Preparing for the next crisis: What can organizations do to prepare managers for an uncertain future?Business Strategy Series,12(2), 51-55.

- Fink, S. (1986).Crisis management: Planning for the inevitable. American management association.

- Hemdi, M.A., & Nasurdin, A.M. (2003). A conceptual model of hotel managers’ turnover intentions: The moderating effect of job-hopping attitudes and turnover culture.Tourism Educators Association of Malaysia,1(1), 63-76.

- Hemdi, M.A., & Rahman, N.A. (2010). Turnover of hotel managers: Addressing the effect of psychological contract and affective commitment.World Applied Sciences Journal,10, 1-13.

- Henderson, J.C. (2004). Managing a health-related crisis: SARS in Singapore.Journal of Vacation Marketing,10(1), 67-77.

- Herrero, A.G., & Pratt, C.B. (1996). An integrated symmetrical model for crisis-communications management.Journal of Public Relations Research,8(2), 79-105.

- Hofstede, G. (2010). Geert hofstede.National Cultural Dimensions.

- Ismail, M.N., & Lim, S.H. (2007). Effects of attitudes, job characteristics, and external market on employee turnover: A study of Malaysian information technology workers. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. University of Malaya.

- Iverson, R.D., & Deery, M. (1997). Turnover culture in the hospitality industry. Human Resource Management Journal, 7(4), 71-82.

- Jaros, S.J. (1997). An assessment of Meyer and Allen's (1991) three-component model of organizational commitment and turnover intentions.Journal of Vocational Behavior,51(3), 319-337.

- Kane-Sellers, M.L. (2007).Predictive models of employee voluntary turnover in a North American professional sales force using data-mining analysis. Texas A&M University.

- Kenny, B. (2007). The coming crisis in employee turnover. Online document.

- Lagadec, P., & Topper, B. (2012). How crises model the modern world.Journal of Risk Analysis and Crisis Response,2(1), 21-33.

- Meyer, J.P., Stanley, D.J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences.Journal of Vocational Behavior,61(1), 20-52.

- Mishra, A.K. (1996). Organizational responses to crisis. Trust in organizations. Frontiers of Theory and Research, 261-287.

- Mitroff, I.I. (2005).Why some companies emerge stronger and better from a crisis: 7 essential lessons for surviving disaster. AMACOM/American Management Association.

- Mitroff, I.I., Pauchant, T.C., & Shrivastava, P. (1988). The structure of man-made organizational crises: Conceptual and empirical issues in the development of a general theory of crisis management.Technological Forecasting and Social Change,33(2), 83-107.

- Mobley, W.H. (1977). Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover.Journal of Applied Psychology,62(2), 237-240.

- Mueller, C.W., & Price, J.L. (1989). Some consequences of turnover: A work unit analysis. Human Relations, 42(5), 389-402.

- Ogbonna, E., & Harris, L.C. (2002). Managing organizational culture: Insights from the hospitality industry. Human Resource Management Journal, 12(1) 33-53.

- Pauchant, T.C., & Mitroff, I.I. (1988). Crisis prone versus crisis avoiding organizations is your company's cultures its own worst enemy in creating crises?Industrial Crisis Quarterly,2(1), 53-63.

- Pauchant, T.C., & Mitroff, I.I. (1992).Transforming the crisis-prone organization: Preventing individual, organizational, and environmental tragedies. Jossey-Bass.

- Pearson, C.M., & Clair, J.A. (1998). Reframing crisis management.Academy of Management Review,23(1), 59-76.

- Pearson, C.M., & Mitroff, I.I. (1993). From crisis prone to crisis prepared: A framework for crisis management.Academy of Management Perspectives,7(1), 48-59.

- Pforr, C. (2009). Crisis management in tourism: A review of the emergent literature. InCrisis Management in the Tourism Industry: Beating the Odds (pp.37-52).

- Price, J.L. (1989). The impact of turnover on the organization. Work and Occupations, 16(4), 461-473.

- Price, J.L., & Mueller, C.W. (1981). Professional turnover: The case of nurses.Health Systems Management,15, 1.

- Ritchie, B. (2008). Tourism disaster planning and management: From response and recovery to reduction and readiness.Current Issues in Tourism,11(4), 315-348.

- Ritchie, B.W. (2004). Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry.Tourism Management,25(6), 669-683.

- Ritchie, B.W., Mair, J., & Walters, G. (2014). Tourism crises and disasters.The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism, 611-622.

- Robert, B., & Lajtha, C. (2002). A new approach to crisis management.Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management,10(4), 181-191.

- Sapriel, C. (2003). Effective crisis management: Tools and best practice for the new millennium.Journal of Communication Management,7(4), 348-355.

- Schein, E.H. (2006).Organizational culture and leadership. John Wiley & Sons.

- Schraeder, M., Tears, R.S., & Jordan, M.H. (2005). Organizational culture in public sector organizations: Promoting change through training and leading by example.Leadership & Organization Development Journal,26(6), 492-502.

- Simons, T., & Hinkin, T. (2001). The effect of employee turnover on hotel profits a test across multiple hotels. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 42(4), 65-69.

- Smallman, C., & Weir, D. (1999). Communication and cultural distortion during crises.Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal,8(1), 33-41.

- Smith, D. (1990). Beyond contingency planning: Towards a model of crisis management.Industrial Crisis Quarterly,4(4), 263-275.

- Then, S., & Loosemore, M. (2006). Terrorism prevention, preparedness, and response in built facilities. Facilities, 24(5/6), 157-176.

- Veil, S.R. (2011). Mindful learning in crisis management.The Journal of Business Communication, 48(2), 116-147.

- Walker, J.R., & Miller, J.E. (2010). Supervision in the hospitality industry-leading human resources. John Wiley and Sons.

- Wang, J., & Ritchie, B.W. (2010). A theoretical model for strategic crisis planning: Factors influencing crisis planning in the hotel industry. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 3(4), 297-317.

- Williams, L.J., & Hazer, J.T. (1986). Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: A reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods.Journal of Applied Psychology,71(2), 219-231.

- Yang, J.T. (2008). Effect of newcomer socialisation on organisational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in the hotel industry.The Service Industries Journal,28(4), 429-443.

- Zainol, N., Rahman, A., Nordin, N., Tazijan, F.N., & Ab Rashid, P.D. (2015). Employees dissastification and turnover crises: A study of hotel industry, Malaysia. SSRN.

- Zopiatis, A., Constanti, P., & Theocharous, A.L. (2014). Job involvement, commitment, satisfaction and turnover: Evidence from hotel employees in Cyprus. Tourism Management, 41, 129-140.