Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 4S

University Entrepreneurial Education, Family Entrepreneurial Experience and Family Business Entrepreneurial Intentions: Mediating Effect of Students Benefits in Palestine

Issa M.H. Smirat, Ph.D. in Strategic Management

Mohd Noor Mohd Shariff, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Abstract

The objective of this study is to examine the mediating effect of student’s benefits on the relationship between university entrepreneurial education, family entrepreneurial experience and family business entrepreneurial intentions in Palestine. The study conducted was based on the outcomes of a survey among 320 undergraduate Palestinian university students. The seven main direct and indirect hypotheses were tested through PLS-SEM to check the structural model. The findings highlighted that students with a family entrepreneurial experience and university entrepreneurial education reported a higher entrepreneurial intention than students who benefits from family networks without such a background. The variables that positively influenced the family business entrepreneurial intentions of the students were entrepreneurial family experience and effectiveness of university entrepreneurship education. Furthermore, this family entrepreneurial experience mediated the relationship between family entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention, and student benefits mediated the relationship between family entrepreneurial experience and family business entrepreneurial intentions. For this reason, emphasis should be placed on both university entrepreneurial education and family entrepreneurial experience which will increase the tendency of university student’s benefits to choose family business entrepreneurial intentions.

Keywords

Family Entrepreneurial Intentions, University Entrepreneurial Education, Family Entrepreneurial Experience, Student’s Benefits

Introduction

Despite the fact that the unemployment rate in 2019 among youth in the world was over 15 percent, and 38 percent and redoubled from 12 percent in 2007 to 18 percent in 2019 among degrees or higher in Palestine (PCBS, 2020; WB, 2021). Besides, the importance of family businesses for most economies in the world. There is a right smart agreement concerning the importance of family entrepreneurship to stimulate economic development and employment rate (Marja?ski, Su?kowski & Review, 2019). However, the growing age is usually unprepared for a leadership role, wherever 78 percent of family businesses lacked a proper program to teach their rising generation (FBM, 2020).

Scholars planned that families, who still educate themselves can adapt quickly to challenges and position the organization for long-term success (Hughes Jr, Massenzio & Whitaker, 2014). By swing structure in place, families see the rising generation as future leaders and decision-makers within the family system. Further, education will completely influence students’ attitudes, and knowledge of entrepreneurship intentions to start out a business (Orford, Wood, Fisher, Herrington & Segal, 2003). However, the most important source of competitive advantage for future entrepreneurship alignment between family and business is the family power, experience, and culture (Holt & Pearson, 2015; Klein, Astrachan, Smyrnios & practice, 2005). Likewise, the educated method between members of the family, business, and ownership was thought-about because the main source of success (Higginson & research, 2010; Tagiuri & Davis, 1996).

In the context of the owned business, it had been all wholly totally different from alternative businesses and correlative with the external surroundings. Theoretically speaking, to try a family business, it had been suggested to qualify teens in management subjects and technologies (Kongolo, 2010). Doing business may be learned from society, traditions, innovations, and the surroundings (De Massis, Frattini, Kotlar, Petruzzelli & Wright, 2016). It had been seen that individuals of high entrepreneurship interest family-owned businesses (Marja?ski et al., 2019). In Palestine, they consist the foremost of the economy with less support from governmental bodies, promoting personal traits, and family funding (The World Bank, 2018; Sabri, 2010). However, the governmental efforts to eliminate the Israeli occupation restrictions to develop the entrepreneurial sector were inconclusive (WB, 2021). Conversely, the recommendations to market the entrepreneurial culture were questionable (Al Shobaki, Abu-Naser, Amuna & El Talla, 2018). Studies demonstrate that doing business in Palestine is usually problematic, complex, instability dominated by the service sector, and no national currency (WB, 2021). It had been moderate in the Human Development Index indicators (The World Bank, 2018; Sabri, 2010; Enshassi, Al-Hallaq & Mohamed, 2006).

By definition, the entrepreneurial intention has mentioned the family business background (FBB) and offspring career selection (Georgescu & Herman, 2020); Transferring family benefits values, financial and social capital (Newbert & Craig, 2017; Ke, 2018). Besides, owners have to prepare firms for the next-generation regular operating and management positions (Walsh, 2011). However, personal skills, family, and structure development as necessary factors for family business to maneuver to successive generations (Davis, 1986). Indeed, only 41 percent of businesses within the world were prepared for the longer term of succession. In place seventieth of current family business leaders don't have a succession plan (Calabrò, 2019). Sangster (2019) has emerged that the successive generation isn't interested or ready to guide the business, and therefore the leadership has not thoughtfully planned or prepared for leadership transition.

By drawing on the theory of planned behavior, the study promotes the discussion on the determinants of family business entrepreneurship intentions. An understanding of the education priorities, families, businesses, universities' efforts to develop entrepreneurship orientations is vital. To know what style of youth show entrepreneurial intentions and to what extent entrepreneurial intentions are influenced by education. As for uniqueness, the research focuses on the effect of entrepreneurial family expertise on the family members’ education choice at the university level and also the entrepreneurial intention of students. The main question of the study is, does the family business involvement with experience in the offspring university entrepreneurial education, and benefits effect the family business entrepreneurial intentions. The objective of this study is to investigate the direct and indirect relationships through mediations of the university entrepreneurial education and therefore the students’ benefits on the relationship between family entrepreneurial experience and family business entrepreneurial intention, with a focus on Palestine. Investigating the motives that drive family graduate students for entrepreneurship is highly significant given the importance of entrepreneurship for job creation and economic growth. University students will provide information on their parents’ involvement and influence throughout their education.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) suggests that performance of a specific behavior is a function of the intention to perform such behavior. Ajzen (1988) proposed that subjective norm has a positive influence on personal attitude of family living environment, friends and colleagues. More theories share in the idea. According to (Dyer’s, 1995; Bandura & Walters, 1977) social factors via parents including the educational experiences, individual factors, and economic factors are related to entrepreneurial careers, attitudes and traits. Globally, 46 percent of young workers are own-workers or family workers (Global Employment Trends for Youth, 2020). Young people may be outside the labor market for several reasons including education and family responsibilities. However, young people education ensures better skilled to cope with the changes in the work (Chlosta, Patzelt, Klein & Dormann, 2012).

The parents and family members’ priorities was reinforced by the TPB. Parents are responsible for earning of living, career oriented, status execution (Eddleston, Veiga & Powell, 2006; Chlosta, Patzelt, Klein & Dormann, 2012). It supposed that individuals act and live stimuluses the way those think about their own ability to take actions. In turn, behavioral intention is a function of individual’s attitude toward the behavior and subjective norm (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). An individual’s behavior is determined by his intention to perform that behavior. Furthermore, it was argued that both positive and negative feedback of parents play a role in influencing their children’s behavior (Bandura, 1986). For example, children select the educational specialization as parents do (Russel et al., 2003). Parents play a more significant part in their children’s occupational choice. Thus, parental model of influencing their offspring attitude towards becoming self-employed was sustained by the TPB (Chlosta et al., 2012). The advanced degree of subjective norms will advance a higher degree of personal attitude toward entrepreneurship (Heuer, & Kolvereid, 2014).

Empirically, the TPB in the family entrepreneurship context was conducted. It was applied among first-year undergraduate students at a Norwegian business school, to predict employment status choice intentions (Kolvereid, 1996). It is found that all three determinants are: attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. Krueger, et al., (2000) tested the senior university business students facing career decisions. Gird & Bagraim (2008) examined entrepreneurial intention of personality traits, situational factors and prior exposure to entrepreneurship, and demographics on final-year commerce students at two universities in the Western Cape, South Africa. To summarize, there are many approaches for studying entrepreneurial intention but the most popular model is the TPB (Ajzen, 1991). They found that attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control had significant effects on entrepreneurial intention (e.g. Gird & Bagraim, 2008; Kolvereid, 1996). Overall, these results are consistent with those of applications of this theory on other disciplines included family business entrepreneurship involvements (Sharma, Chrisman & Gersick, 2012).

Nevertheless, some reviewed studies are inconclusive, they found only partial support for the theory of planned behavior. Most studies dedicated individual’s development including role university, career preferences (Betáková, Havierniková, Okr?glicka, Mynarzova & Magda, 2020; Philipp Sieger & Monsen, 2015). This study shields the lake of knowledge in the parents’ role in major’s selection related to entrepreneurship intent suggested by (Krueger, 2007). Krueger argued that the family firm context, should be taken into consideration to investigate the entrepreneurship intent. However, the interaction relationships between student university entrepreneurship major, family entrepreneurship experience and student benefits need more discussions in the Arab world context. Specifically, the students deliver information about their parents’ involvement in the family business. The family influences an entrepreneur's career with various family and entrepreneurial dynamics intersect. They Include, early experiences, power and culture in the entrepreneur's family of origin (Tarling, Jones & Murphy, 2016); family involvement and support of early start-up activities (Edelman, Manolova, Shirokova & Tsukanova, 2016); employment of family members in the new venture (Muñoz-Bullón, Sanchez-Bueno & Nordqvist, 2019); and involvement of family members in ownership and management succession (Pittino, Chirico, Henssen & Broekaert, 2019). Moreover, variances among firm goals because of the meaning that family members give an emotional ownership to the firm (Pieper, 2010). In which, this attitude changes the firm aim itself from profit maximizer to utility maximizer as a human institution with different possible meanings and personal decision-making process arises (Carney, 2005).

Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) was considered a key that explains the determination to start a business or to become self-employed. EI was defined as “desires to own or start a business”(Bae, Qian, Miao, Fiet & practice, 2014), characterize the antecedent of entrepreneurial and required of behavior in most career choice models (Zhang, Duysters, Cloodt & journal, 2014). Previous studies (e.g. Franco et al., 2010; Pruett et al., 2009; Litzky et al., 2020) have set up that entrepreneurship intentions can be affected by different factors including personal background factors. Besides that, Shapero’s Entrepreneurial Event Model views firm creation resulting from interactions between contextual factors, which would act through their influence an individual’s perceptions (Shapero, 1975). Shapero emphasizes the importance of cultural and social factors perceptions, in predicting the intention to act in some specific ways.

We test our hypotheses by using data of the family backgrounds of 320 students in Palestinian universities. Our study contributes to the family entrepreneurship literature in several ways. First, to identify the effect of parental role on individuals’ chain of decisions to become an entrepreneur or self-employed. For example, prior studies have shown that parents influence the self-employment decisions of their children (Nguyen, 2018), but these studies do not explain the parental role in majoring university in Palestine family business context of unstable environment. Second, the family business literature need more investigations how characteristics of the parents and motivation of generation (Hradský & Sadílek, 2020), their family business (Porfírio, Felício & Carrilho, 2020), and family dynamics (Marques, Ferreira, Zopounidis & Banaitis, 2020) to motivate family members to take over family businesses industry structure. Nevertheless, the study will discuss the student benefits, where family members’ entrepreneurs’ abilities, skills and values can develop a family business financial and non-economic goals. Non-economic goals include family perpetual and assets. They interaction between personal, organizational and context features of the family business development. In which it is related to family culture, commitment, values, and both firm and the family goals. Family effect on family business performance cannot be seen only from a positive of stewardship theory or a negative of agency theory angle (Alves, Gama, Augusto & Development, 2020).

The Family Business Entrepreneurial Intentions

Scholars pointed out why some family firms of high heterogeneity are more entrepreneurial than other firms by driver factors of management and involvement in business (Herrera & de las Heras-Rosas, 2020; Herrero, 2018; Revilla, Perez-Luno & Nieto, 2016; Shepherd, 2016). By meaning, there is overlapping relationships between family and business beside interactions of family power, experience and culture (Klein et al., 2005). Maturing in a family where family members are the owners and managers of a business. They represent the actual context in which social relationship, offspring choices of friends, university majors and career intentions are made (Wang, Wang, Chen & Journal, 2018).

Students grow in the family business context where the business is organized and managed by the family members with a transgenerational perception (Shen & Management, 2018). Businesses are often closely wide-open to the challenges and opportunities related to family entrepreneurial intention. The family and business involvement strengthens the impact of entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Wang et al., 2018), where previous life practices of the family play a key role in molding a person's characters, thinking, beliefs and attitudes (Sigel, McGillicuddy-DeLisi & Goodnow, 2014).

Empirically it was revealed that parent’s has a major influence on students’ decisions regarding the selection of a business major in university (Kumar & Kumar, 2013). Their influence was emerged as a key theme in student decision making processes of college choice, major, and career decision making (Workman, 2015). Family influence was correlated in expected ways with family commitment, work choice, work values, calling, and occupational engagement (Fouad, Kim, Ghosh, Chang & Figueiredo, 2016). Furthermore, it has been found that the parents’ positive role models positively relayed to offspring to start their own firm where students with a (FBB) are actively involved in their parents’ business (Cie?lik, van Stel & Development, 2017). This may be related to family support in terms of learning effects, or strengthened perceptions about mastery of the challenges, entrepreneurial career and heightened perceived behavioral control (Carsrud, Renko-Dolan & Brännback, 2018). Family members and in particular parents may be seen as powerful of adults (Bandura, 1986),

It is abstracted that the higher intention to become an entrepreneur among students with entrepreneurial parents, compared to students without entrepreneurial parents, depends on the parents’ entrepreneurial performance. In other words, a student who studies entrepreneurship at the university will go to entrepreneurial developments next to graduation, and students whose parents are entrepreneurs will go to entrepreneurial projects. Entrepreneurship education and the entrepreneurial climate are key determinants of entrepreneurial intentions and activities (Bosma & Kelley, 2018). Edinyang (2016) emphasizes that students can learn by observing their parents’ actions. The parental role models increased the individual chance to become self-employed, create new business and students choose an entrepreneurial career if their parents were entrepreneurs (Chlosta et al., 2012; Fernández-Pérez et al., 2015; Bosma & Kelley,2018). A considerable body of literature evidenced that students of prior experience, age, gender, education, work experience and role models, family background and education effect family entrepreneurship starting (Fatoki, 2014; Hatak et al., 2015, Quan, 2012). Relationship of self-efficacy and parental role models as well as attitudes toward entrepreneurship have been established in numerous studies. The direct and indirect effects was supported (BarNir et al., 2011).

Family Entrepreneurial Experience and Family Entrepreneurial Intentions

Family members with entrepreneurial backgrounds are more likely to start their own businesses or to join the family business (Eesley & Wang, 2016; Nguyen, 2018); to influence offspring to become family business leader (Hoffmann, Junge & Malchow-Møller, 2015; Garcia, Sharma, De Massis, Wright & Scholes, 2019). However, family office indicators show that the rising generation is often unprepared to take on a leadership role. A 41 percent of families identified “helping the rising generation become productive adults is one of their top priorities. But, 78 percent of families lacked a formal program to educate their rising generation (FBM, 2019). Despite that, 45 percent of family business’ leaders’ states that the family business will stay in the hands of the family in the future, 37 percent showed the next CEO will be a family member. 48 percent declares that their choice to select the next CEO is based on the level of interest in the business, and 23 percent said they will select the most qualified (Calabrò, 2019). Sørensen (2007) showed that family members with self-employed parents are twofold as likely to become self-employed or because they have superior entrepreneurial abilities.

It was seen that students of (FBB) should be related to their capabilities, education and resources to pursue an entrepreneurial calling (Wahjono, Idrus & Nirbito, 2014; Zellweger, Sieger & Halter, 2011). However, some economies have more entrepreneurs driven by a family business tradition than others. 50 economies indicated that continuing a tradition family business is a main motive to start a business (Sieger, Fueglistaller, Zellweger & Braun, 2018). It help to keep on continuity, maintaining family unity, protecting the family name in the market, and to keep the family heritage and wealth as the most important benefits of the family involvement (Jaskiewicz, Combs & Rau, 2015).

In addition, the good father-son relationship was viewed as one of the most critical factor that positively affects the outcomes of FB succession (Ahmadi Zahrani, Nikmaram & Latifi, 2014).

On the opposite side, conflict among family members is negatively affect succession outcomes. However, students whose parents are family or self-employed score higher entrepreneurial intention (Nguyen, 2018). Entrepreneurial families have positive effect on their offspring toward business starting and doing. In Western cape, Romanian, and Germany universities indicate that prior experience, family and parents experience to entrepreneurship was explaining entrepreneurship intention (Walter & Dohse, 2012; Georgescu & Herman, 2020).

To navigate change, Babson college figured out that entrepreneurial leaders need a strong functional knowledge, skills and vision (Babson, 2021). It has become a conventional wisdom that transferring the family business knowledge to the rising generation is a dynamic process of education (Harvey, Cosier, Novicevic & Entrepreneurship, 1998; Le Breton–Miller, Miller, Steier & practice, 2004). This knowledge could increase FB members’ interactions, involvement and decisions in functional business areas, emotional problems and disputes related to business. On the other hand, the reasonable educated process between ages will facilitate transferring knowledge between external environment from business owner to familial successors (Higginson & research, 2010; Tagiuri & Davis, 1996). Furthermore, students whose parents are self-employed score higher entrepreneurial intention (Nguyen, 2018). Though, the factors that determine the individual’s decision to start a venture are still not completely clear. Therefore, there is a need to clarify which elements play the most influential role in shaping the graduated personal decision to start a business. Therefore, we set up the following hypotheses:

H1: For students, there is a positive relationship between family entrepreneurial experience and family entrepreneurial intentions toward family businesses in the university degree stage.

Student’s Benefits and Family Entrepreneurial Intentions

Student’s benefit refers to the resources within the family that can be made available to the business. A student has benefits, because he has a family that has additional resources of its liabilities (Sorenson & Bierman, 2009). The closest concept to student’s benefits is the term of family benefits or family capital. Student as family member can benefit from the family networks with others businesses or individuals, customers, social, human and financial resources (Danes, Stafford, Haynes & Amarapurkar, 2009).

Within benefits, students can hire different kinds of resources because it exists within the family relationship (Dyer Jr & Dyer, 2009). It assists as the main source for new business. Entrepreneurs of high performing firms engage in networking more than entrepreneurs of low performing firms (Boso, Story & Cadogan, 2013). It refers to the kind of relationship that has economic impacts. These benefits include opportunities, resources and goodwill, in which they help students to do or start a business (Carlock & Ward, 2010; Chuairuang, 2013). Similarly, these benefits describe such results as entrepreneurial and financial benefits one receives from one’s relationships with others (Agbim & Innovation, 2019; Shi, Shepherd, Schmidts, & Research, 2015)

The financial and non-financial benefits improve the ability of family members as businesses in collecting resources that can improve their performance (Cruz, Justo & De Castro, 2012; Mazzi, 2011). it facilitates assistance knowledge transfer and provides access to new business opportunities (Boyd, Royer, Pei & Zhang, 2015). Thus, it positions the family business in interacts more closely with more customers or clients. It can enhance ability by strengthening the capacity of a family firm’s dominant coalition to govern and by providing access to valuable resources (Zellweger, Chrisman, Chua & Steier, 2019). The benefits include the inter-relationship between entrepreneurs and their contacts for business purposes. They comprise family members, friends, relatives, business contacts, social associations and clubs (Chuairuang, 2013). Students also obtain resources to compete successfully with others and address the main challenges to do business (Shi et al., 2015).

The analysis decides that parents resource such as family business owners are the most important variable for next generation to understand motivations, difficulties and benefits they face (Huarng, Mas-Tur, Yu & Journal, 2012). On the other hand, the lake of business owners’ benefits, skills and experience of new business ventures accompanied fail in different periods of business life cycle. Similarly, without a systematic process to prepare the family members rising generation, it is difficult to find competent managers and executive leadership (Sangster & Claudia, 2019). For instance, children who know their family history show higher levels of emotional well-being, making it great for the family and for the business (Dunn & Wyver, 2019). Parents ascertain to be an essential part of young career development and positively effects on student performance (Amatea, Daniels, Bringman & Vandiver, 2004).

In order to consider family business as a desirable employment choice, the real challenge for family sons and daughters is gaining the benefits from family power and acquiring the relevant education and skills in entrepreneurship. Benefits as an entrepreneurs' values could be a mix of compulsory and optional activities. Benefits link the evolution of the young entrepreneurs' values and the successful generational transition within each family business, rather than interactions between the role of the young entrepreneur and the family and organizational contexts (Lazzarotti, Minelli & Morelli, 2020). Therefore, we set the following hypotheses:

H2: For students, there is a positive relationship between students’ benefits and family business entrepreneurial intentions.

H3: For students, there is a positive relationship between students’ benefits and family entrepreneurial experience.

H4: The students’ benefits mediate the relationship between the family entrepreneurial experience from the family business networks' in the university degree stage and family business entrepreneurial intentions.

University Entrepreneurship Education and Family Business Intentions

The family business definition describes the interrelated relationship between family, business and ownership. Furthermore, family members’ involvement influence family business performance (Gill & Kaur, 2015). However, a natural desire to keep the business within the family means families have to make decisions of when and how to transfer management and ownership to the next generation (Devins, 2018). It is difficult to find competent managers and executive leadership for transaction success without family involvement in educating their members systematically to prepare the rising generation (Sangster & Claudia, 2019). Although the results from 11,230 individuals in 32 countries that supported entrepreneurship education as a stronger factor in entrepreneurial activity (Walter & Block, 2016). There is no final conclusion regarding the (FBB) relationship with educating offspring about family organization issues and entrepreneurial family projects, this relationship still needs further discussion (Walter & Block, 2016).

Shariff & Saud (2009) found that the Malaysian university students’ in various education based, demographic and (FBB) are statistically significant to entrepreneurial intention. It was reported that people who have attained higher levels of education have higher choice of employment and tend to be opportunity-driven entrepreneurs. At the global level, millennial family business leaders are highly educated and have a higher appreciation for a work, where 39 percent has the highest level of education master’s or doctorate (Hart et al., 2020). Accordingly, Daspit, Chrisman, Sharma, Pearson & Long, (2017) supported that there is a real need to educate the entrepreneurial orientation in order to deliver entrepreneurial behaviors in family businesses. It was revealed that the current faculty and type of high school of students were significant factors in the entrepreneurial intention in different environments (Tala?, Çelik & Oral, 2013).

Furthermore, taking a strong education supports the personal shape, develop a vision, experience and identity as a future of family business owner (Ghee, Ibrahim & Abdul-Halim 2015). Transactions success depends on leadership skills with primary discretion over the enterprise (Lacy, Haines & Hayward, 2012). Preparing the incoming family member for the next specific issues that arise in a company on a day-to-day basis (Tatoglu, Kule & Glaister, 2008). However, in the FBB, with higher education and those still in education were more likely than their colleagues to consider it feasible to become an entrepreneurial in the next five years (Zellweger et al., 2019). Despite CEOs thinks that education is the most critical development issue for the future success, existence and continuity (Salameh, 2017). The family business necessity existence and continuity is related to education. But, cultural norms blocks the family business future talks after the parents die, mainly regards to financial matters (Lubatkin et al., 2005). As that, the unskilled family members can increase the businesses weakness and threaten their existence and continuity (Mussolino, Cicellin, Iacono, Consiglio & Martinez, 2019).

Family business magazine (2019) projected that, families ought to keep the required learnt of academic programs in business activities. It’s found that the foremost success privately held corporation has invested with in their family education. They have to be concerned of ownership, and business systems; communication and conflict resolution skills; business’s purpose, function, competition, advantages, and money structure. Members should perceive however their family governance structure works. Others planned the education priority is governance, entrepreneurship, and business matters (Neubauer & Lank, 2016; Schwass & Glemser, 2016). A consulting group (2017) assured that if the current family homeowners conceive to continue the private corporation for successive generations and extended it to their kids. Besides a lot of formal education, they must reach the high colleges, to be told concerning the trade or variety of business students. Higher education stimulates entrepreneurial intentions among students, create jobs, employment, sustainable development goals (Herman & Stefanescu, 2017). It is powerfully united among forty-nine percent of various country citizens’, that faculty education had helped them to develop a way of initiative. The education gave them the talents, interested and ability to change them to become an businessperson or perceive the role of entrepreneurs in society (Sáez-Martínez, González-Moreno, Hogan & Journal, 2014). Education level shows much significance altogether these impact factors have incontestable that parental work experiences have vital effects on offspring which offspring learn from their parents’ experiences’ (Nguyen, 2018). Fayolle & Gailly (2015) highlighted that students with previous entrepreneurship backgrounds can perform higher in entrepreneurship understanding. Samples from seventy-three business environments showed that student expertise, access to beginning a replacement business are associated with freelance intention (Zellweger et al., 2011; Bae, Qian, Miao & Fiet, 2014; Fayolle & Gailly, 2015).

In detail, students of entrepreneurial families are active in access to money and social capital. At the university education stage compared with students of non-entrepreneurial background families will deciphering business designing and market research techniques (Sieger, Cobben & Hovestadt, 2019). The revision of Ismail, et al., (2012) indicated there is a high prospect that students of entrepreneurial courses be inspired to associate an entrepreneur. Among students, entrepreneurial education was considered an effective tool to entrepreneurial intentions (Liñán, 2004). Globally, the university education context plays a really vital role in entrepreneurship intentions (Sieger et al., 2018). Therefore, we set the following hypotheses:

H5: For students, there is a positive relationship between university entrepreneurial education and the family business entrepreneurial intentions in the university degree stage.

H6: For students, there is a positive relationship between family entrepreneurial expertise and university entrepreneurial education within the university degree stage.

H7: For students, the university entrepreneurial education mediates the link between the family entrepreneurial expertise and the family business entrepreneurial intentions within the university undergraduate stage.

In other words, the family entrepreneurial expertise can influence the university entrepreneurial education that successively, influences private family business entrepreneurial intentions.

The Proposed Model

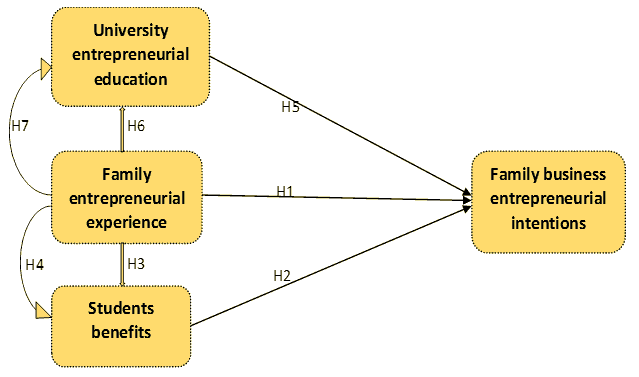

Scholars have recognized a broad rationalization to retain closed corporation continuity for following generations. They mentioned the interaction between personal, structure, and context characteristics of the Family business growth (Porfírio, Felício & Carrilho, 2020), governance (Lee, 2019), leadership (Wijaya & Wijaya, 2019). Depends on the previous discussion we tend to propose the subsequent model: Scholars have recognized a broad rationalization to retain closed corporation continuity for following generations. They mentioned the interaction between personal, structure, and context characteristics of the family business growth (Porfírio, Felício & Carrilho, 2020), governance (Lee, 2019), leadership (Wijaya, & Wijaya, 2019). Depends on the previous discussion we tend to propose the subsequent model: as shows in Figure 1.

Methodology and Research Design

Data Collection Method

An instructive empirical study was conducted supported a form that was applied on undergrad students of economic and non-economics schools in Palestinian universities. A straightforward stratified random sample technique was used. A complete of 450 questionnaires were distributed face to face among students within the university geographic region. Hebron, Palestine polytechnic institute, Bethlehem, Palestine Aliya, and Al-Quds University. 320 questionnaires were collected. The response rate is seventy-one percent. Response rate is valid relating (Uma & Roger, 2013) within which it's over 30 percent. Twenty-six questionnaires were excluded. 65.3 % of collected papers were utilized in the analysis. The form consists of 2 sections; the primary section is for the sample demographics; the second section was to measure the constructs of the analysis model.

Study Population and Sample profile

According to the PCBS (2018), there are twenty-four universities in Palestine with 124621 college students. The chosen universities are representative, within which they're non-public and public; regular and open study. The scholars are from all Palestine areas of geographic region and national capital. Universities are Hebron, Palestine Polytechnic School, Bethlehem, Palestine Aliya, and Al-Quds Open University (Appendix1). Our choice was restricted to undergraduate students, considering that these can be characterized as able to tackle their skilled careers and categorical their own selections (Shirokova, Osiyevskyy & Bogatyreva, 2016). The sample size is between is 382 and 384 depends on (Krejcie & Morgan, 1970).

Measures and Research Instruments

The measurements incorporate demographic queries, dependent variable, besides independent variables. The demographics incorporates 9 queries. The dependent variable is family entrepreneurial intention among university students (FEI) was measured in seven points Likert scale, then adjusted to 5 points Likert scale. Because it was advised by the literature the five-point scale seems to be less confusing and will increase response rate (Bouranta, Chitiris & Paravantis, 2009). Applying Likert-type scales to judge the extent of intention as a result of the intention is mostly viewed as reasoning feature (Liñán, 2004). Respondents were asked queries coupled to their entrepreneurial orientation selection once graduation. Otherwise to become self-employed, a family entrepreneur to do, start or manage a business once graduation (Sieger et al., 2018).

The measurements of (Sieger et al., 2018) were integrated in six queries with Zhao, et al., (2005); Wu (2009); (Peng, Lu & Kang, 2013). Independent variables all-round the dependent variable. Any of these independent variables could have an effect on family entrepreneurship intentions among graduate university students. These variables and their relations measures found from the analysis of the hypothesis developed by this model. The independent variables were made into three variables applying five points Likert-Type scales integrated (Nguyen, 2018; Schröder, Schmitt-Rodermund & Arnaud, 2011; Zhao, Seibert & Hills, 2005). They’re University Entrepreneurial Education (UEE) that is measured by six queries. Followed by Family Entrepreneurship Expertise (FEE). It adjusted to measure family entrepreneurial experience by eight queries. Then four questions to measure Students’ Benefits (SB) variable which students will develop their efforts to try and do, run, or add business. (Appendix2)

Research Limitations/Implications

The study was limited to main universities in Palestine. They are public universities, a private one of Palestine Aliya university; and the open education of Al-Quds Open University. The three main education universities represent the main kinds of higher education in Palestine. They educate economic and non-economic, and business subjects. The generalizability of the findings might be limited to this context. Additional quantitative and qualitative research is warranted to explore the external validity of presented findings with regard to other countries, universities and courses.

Respondents Demography

We obtained valid questionnaires from 450 respondents, the sample (N=384) representing the total number of young people in the bachelor level study. This fact indicates the representativeness of the sample. From the total of 294 respondents 40.1% were male, and 63.9% have a family business. A total of 49.6 % of students considered that business subjects was their program of study, about 42% are stay in the 3rd and 4th year level, where 63.3% of them are living in cities. Descriptive results crosstabs of the sample show that around 64%, 188 out of 294 of students are belonging to families with businesses, 58.7% of them are majoring related subjects to their family business, which are distributed between 38 different industries. as shows in Table 1.

| Table 1 Sample Respondents’ Characteristics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Gender | Male | 118 | 40.1 |

| Female | 176 | 59.9 | |

| Living Place | City | 186 | 63.3 |

| Village | 93 | 31.6 | |

| Camp | 15 | 5.1 | |

| Age (years) | 18-20 | 148 | 50.3 |

| 21-23 | 122 | 41.5 | |

| 24-26 | 18 | 6.1 | |

| 27-29 | 3 | 1.0 | |

| >30 | 3 | 1.0 | |

| University level(year) | 1st | 43 | 14.6 |

| 2nd | 127 | 43.2 | |

| 3rd | 78 | 26.5 | |

| 4th | 46 | 15.6 | |

| Family has a business | Yes | 188 | 63.9 |

| No | 106 | 36.1 | |

Data Analysis

Smart PLS version 3.0 a variance based Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to analyze hypotheses generated. PLS is the appropriate technique to analyze method for testing a multivariate, multi-path model (Hair Jr, Sarstedt, Hopkins & Kuppelwieser, 2014). The two-step analytical method of measurement model and the structural model suggested by (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988) was approved. Then the bootstrapping method (5000 resample) to determine the significant level of loadings, weights, and path coefficients (Chin, 1998).

Results

Methods for Data Analysis

From a methodological point of view, we used descriptive statistics, correlations, and PLS-SEM. PLS-SEM followed a sequential two step approach (Hair, Ringle, Sarstedt & Practice, 2011). It includes the assessment of the measurement model and the assessment of the structural model.

The Measurement Model

Convergent validity is the degree to which the construct indicators items should converge or share a high proportion of variance. Accordingly, factor loadings and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of more than 0.5 and Composite Reliability (CR) of 0.7 or above is considered to be acceptable (Hair et al., 2011). As can be perceived from Table below all loadings and AVE are above 0.5 and the composite reliability values are more than 0.7. Therefore, we can conclude that convergent validity has been established.

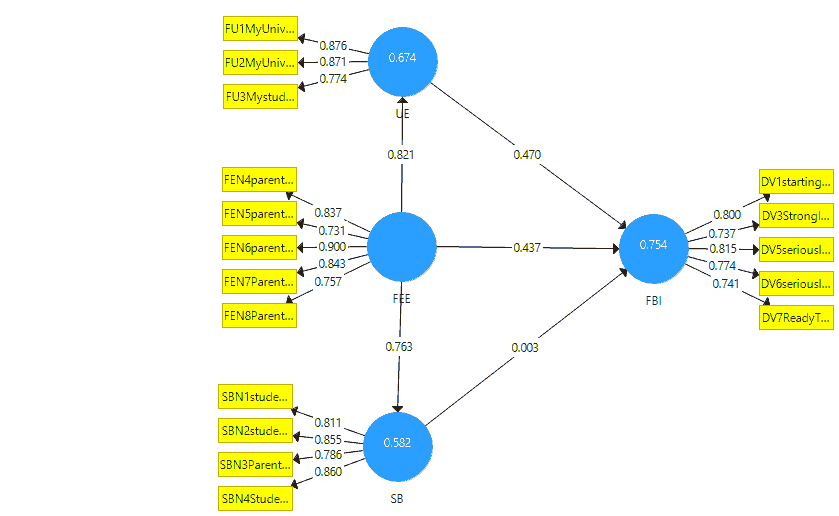

Internal consistency reliability refers to the level to which all items on a particular scale are assessing the same conception measured by Cronbach’s alpha or Composite reliability, in which it is high above 0.80 (Peterson & Kim, 2013). Family Entrepreneurial Experience (FEE), Family Entrepreneurial Intentions (FEI), Student Benefits (SB), University Entrepreneurial Education (UEE), AVE>0.50, CR>0.70 is acceptable. Results suggested high level of internal reliability in which Cronbach’s alpha and Composite reliability are above 0.6 for the constructs (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012) and Convergent validity which AVE is >0.50 (Sarstedt, Ringle, Smith, Reams & Hair Jr, 2014) as shows in Figure 2.

| Table 2 Convergent Validity |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Convergent validity | |||||

| Items | Factor loading | AVE | Cronbach’s alpha |

Composite reliability | R square | |

| Family entrepreneurial intentions | FEI1 | 0.800 | 0.596 | 0.886 | 0.898 | 0.754 |

| FEI3 | 0.737 | |||||

| FEI5 | 0.815 | |||||

| FEI6 | 0.774 | |||||

| FEI7 | 0.741 | |||||

| Family entrepreneurial experience | FEE4 | 0.837 | 0.630 | 0.884 | 0.911 | |

| FBI5 | 0.731 | |||||

| FEE6 | 0.900 | |||||

| FEE7 | 0.843 | |||||

| FEE8 | 0.757 | |||||

| University entrepreneurial education | UEE1 | 0.878 | 0.708 | 0.794 | 0.879 | |

| UEE2 | 0.871 | |||||

| UEE3 | 0.774 | |||||

| Student benefits | SB1 | 0.811 | 0.686 | 0.848 | 0.897 | |

| SB2 | 0.858 | |||||

| SB3 | 0.786 | |||||

| SB4 | 0.860 | |||||

Discriminant Validity

Numbers between brackets in the table below, shows the square root of AVE of all constructs Family Entrepreneurial Intentions (FEI), Family entrepreneurial experience FEE, University entrepreneurial education UEE and Student benefits SB are greater than the correlation between latent construct suggesting adequate discriminate validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). as shows in Table 3.

| Table 3 Discriminant Validity of the Constructs |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | FEI | FEE | UEE | SB |

| FEI | 0.772 (0.878) | |||

| FEE | 0.797 | 0.794 (0.891) | ||

| UEE | 0.859 | 0.813 | 0.841(0.917) | |

| SB | 0.734 | 0.744 | 0.804 | 0.828 |

The Structural Model

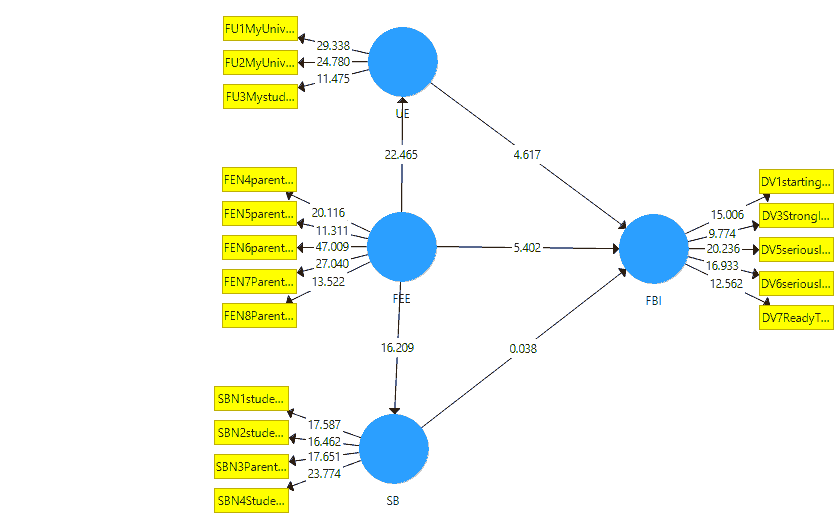

The study applied the standard bootstrapping procedures with a number of 5000 bootstrap sample and 294 cases to evaluate the significant of path coefficients (Hair et al., 2014). As the following figure showed the direct and indirect relationships.

The structural model represents the relationship between constructs or latent variables that were hypothesized in the research model. Figure and Table, shows the results of the structural model from the PLS output. The Figures (3) and Table (4) below showed the direct relationships model. Results hypotheses 1 displayed a significant relationship between Family Entrepreneurial Experience (FEE) and family business intentions where t (27.749) with p value (0.000).

With Regards to the hypotheses 2, there is no significant direct relationships between student benefits and family business intentions.

H3: there is a positive significant direct relationship between family entrepreneurial experience (FEE) and student benefits with t (16.209) and P value (0.000) to run, do, self-employer, or starting a business.

Respects to hypotheses 6 these is a significant relationship between Family Entrepreneurial Experience (FEE) and university entrepreneurial education (FUE) with t (22.465) and p value (0.000). The hypotheses where hypotheses 5 was approved, where there is a positive significant direct relationship between university entrepreneurial education and family business intentions with t (4.617) and p value (0.000). as shows in Table 4.

| Table 4 The Direct Effect |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotheses | Direct relationships | ß Original sample | Mean | SD | T statistics | P value | R square |

| 1 | FEE->FBI | 0.437 | 0.436 | 0.081 | 27.749 | 0.000 | 0.754 |

| 2 | SB->FBI | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.090 | 0.038 | 0.970 | |

| 3 | FEE->SB | 0.763 | 0.765 | 0.047 | 16.209 | 0.000 | |

| 4 | UE->FBI | 0.570 | 0.479 | 0.102 | 4.617 | 0.000 | |

| 5 | FEE->UE | 0.821 | 0.820 | 0.037 | 22.465 | 0.000 | |

Family Business Intentions (FBI), Family Entrepreneurial Experience (FEE), Student Benefits (SB), University Entrepreneurial Education (UEE).

The Indirect Relationships Model

As shows in Figure 3.

In the indirect mediated relationships, the 4 hypotheses analysis has proved that family entrepreneurial environment has no interaction relationship with students’ benefits and family business entrepreneurial intentions where t (0.037) and p value (0.970). But, the 7 hypotheses analysis showed that university entrepreneurial education will influence the family entrepreneurial environment which, in turn, influences family business entrepreneurial intentions with t (4.459) and P value (0.000). as shows in Table 5.

| Table 5 Family Business Entrepreneurial Intentions |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect relationships | Original sample | Mean | SD | T statistics | P value | |

| 1 | FEE->SB->FBI | 0.003 | -0.00 | 0.070 | 0.037 | 0.970 |

| 2 | FEE->UE->FBI | 0.386 | 0.393 | 0.087 | 4.459 | 0.000 |

Results and Discussions

The applied of the results as important to statistical data (PCBS, 2018) supports expanding practical education in universities and through rapid skills training programs and accelerators connected with public education programs. The number of higher education institutions graduates in Palestine reached 124, while the local market accommodates 8,000 job opportunities for individuals (20-29 years), which means that 80% of graduates have no job opportunities. Our results showed that the study variables of student Family Business Entrepreneurial Intentions (FBEI) was determined by Family Entrepreneurial Experience (FEE), Student Benefits (SB) and University Entrepreneurial Education (UEE). They explain 75.4% of the variances of students intended to become family business entrepreneurs. The study is in the line with the (Elfarra, 2017; Orford et al., 2003; WB, 2018) finding where students and graduates were positive towards entrepreneurship attitudes that Gaza's universities provide to them, with mean value (71%). For Palestine, this finding was so important for university programs planning. In which entrepreneurship university programs will be an important indicator to reduce the unemployment rate. World Bank study (2018) found that 19 new startups in are created annually by highly educated founders. 85 per cent created by a university degree and 27 per cent with graduates in Palestine. It is higher than Lebanon or Tanzania that share a similar technology landscaper (WB, 2018).

Further, the evidence that education can positively influence students’ attitudes, and knowledge of entrepreneurship to start a business (Orford et al., 2003). Unfortunately, the unemployment rate among the youth (18-29 years) in Palestine reached 38% in 2019. Data also showed that the higher unemployment percentage among the youth was for holders of intermediate diploma and higher, where this percentage reached 52% during 2019. The holders of bachelor degree or above in Palestine increased from 120 young persons per 1000 in 2007 to about 180 in 2019 (PCBS, 2020). For the analyzed variables, cross tabulation descriptive found that 188 (64%) of students are belonging to families that have businesses. 134 (45.6%) of them are focused in the main cities in the West Bank. This wants additional effort analysis in villages and camps, with further policies toward other communities.

The analysis considers that those with no levels of entrepreneurial education and non-entrepreneurial family experience were had never thought about starting up a business. Oppositely, people with high levels of education, with an entrepreneurial family background and respondents with benefits showed that they were currently taking the necessary steps to start up, or had once started up, a business. It is in the line with Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019/2020 Report (Hart et al., 2020)

Our results showed that 63.9% of students studied majors that related to their family businesses and considered arrangements of entrepreneurship education. This very high percentage was surprising, taking into account that only 49.6% of respondents were business students whose curricula contained entrepreneurship courses or entrepreneurship-related courses. However, this can be explained by the existence of accounting 14.6%, management 23.8%, economics 1.7, finance 7.1% and marketing 2.4%. In the global entrepreneurship monitor report, people start or run a business by 35 out 54 because of entrepreneurial education at school stage, while 50 out 54 of the surveyed do that because of the entrepreneurial education at post–school stage (Hart et al., 2020). But, the surveyed people in some developed countries, 15% in Japan and 10% in Hungary mentioned that that their preference to be self-employed was influenced by family members or friends experience. To support that the higher the level of education, the more likely the possibility of starting a business (Walter & Block, 2016). There are significant differences in entrepreneurial intentions according to students field of study in the university (Sieger et al., 2018; Walter & Block, 2016), in which entrepreneurial intentions are being higher among business students than other students (e.g. engineering sciences and social sciences students).

References

- Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality and behavior. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Al Shobaki, M.J., Abu-Naser, S.S., Amuna, Y.M.A., & El Talla, S.A. (2018). The level of promotion of entrepreneurship in technical colleges in palestine.

- Amatea, E.S., Daniels, H., Bringman, N., & Vandiver, F.M. (2004). Strengthening counselorteacher-family connections: TheFamily-school collaborative consultation project. Professional School Counseling, 8(1), 47-55.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986, 23-28.

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R.H. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-hall. 1

- BarNir A., Watson W.E., & Hutchins H.M. (2011). Mediation and moderated mediation in the relationship among role models, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial career intention, and gender. Journal of Applied Social Psycholog,. 41, 270–297. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00713.

- Bosma N., Kelley, D. (2018). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Global Report 2018/2019. The Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA)

- Bouranta, N., Chitiris, L., & Paravantis, J. (2009). The relationship between internal and external service quality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management.

- Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, 249-265.

- Carr, J.C., & Sequeira, J.M. (2007). Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: A theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of business research, 60(10), 1090-1098.

- Chlosta, S., Patzelt, H., Klein S.B., & Dormann, C. (2012). Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Small Business Economics, 38, 121–138. 10.1007/s11187-010-9270-y

- Cui, J., Sun, J., & Bell, R. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial mindset of college students in China: The mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. The International Journal of Management Education, 100296.

- Daspit, J.J., Chrisman, J.J., Sharma, P., Pearson, A.W., & Long, R.G. (2017). A strategic management perspective of the family firm: Past trends, new insights, and future directions. Journal of Managerial Issues, 29(1).

- Dunn, R., & Wyver, S. (2019). Before ‘us’ and ‘now’: Developing a sense of historical consciousness and identity at the museum. International Journal of Early Years Education, 27(4), 360-373.

- Dyer Jr, W.G. (1995). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial careers. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 19(2), 7-21.

- Dyer Jr, W.G., & Handler, W. (1994). Entrepreneurship and family business: Exploring the connections. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 19(1), 71-83.

- Eddleston, K.A., Veiga, J.F., & Powell, G.N. (2006). Explaining sex differences in managerial career preferences: The role of gender self-schema. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(2), 437–445.

- Edelman, L.F., Manolova, T., Shirokova, G., & Tsukanova, T. (2016). The impact of family support on young entrepreneurs' start-up activities. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(4), 428-448.

- Edinyang, S.D. (2016). The significance of social learning theories in the teaching of social studies education. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology Research, 2(1), 40-45.

- Eesley, C.E., & Wang, Y. (2016). Social influence in entrepreneurial career choice: Evidence from randomized field experiments on network ties. Boston U. School of Management Research Paper, (2387329).

- Enshassi, A., Al-Hallaq, K., & Mohamed, S. (2006). Causes of contractor's business failure in developing countries: the case of Palestine. Causes of contractor's business failure in developing countries: The case of Palestine, 11(2).

- Fatoki, O. (2014). The entrepreneurial intention of undergraduate students in South Africa: The influences of entrepreneurship education and previous work experience. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(7), 294.

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of small business management, 53(1), 75-93.

- Fernández-Pérez V., Alonso-Galicia P.E., Rodríguez-Ariza L., & del Mar Fuentes-Fuentes M. (2015). Entrepreneurial cognitions in academia: exploring gender differences. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30, 630–644. 10.1108/JMP-08-2013-0262.

- Fouad, N.A., Kim, S.Y., Ghosh, A., Chang, W.H., & Figueiredo, C. (2016). Family influence on career decision making: Validation in India and the United States. Journal of Career Assessment, 24(1), 197-212.

- Franco, M., Haase, H., & Lautenschläger, A. (2010). Students' entrepreneurial intentions: An inter?regional comparison. Education+ Training.

- Garcia, P.R.J.M., Sharma, P., De Massis, A., Wright, M., & Scholes, L. (2019). Perceived parental behaviors and next-generation engagement in family firms: A social cognitive perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(2), 224-243.

- Georgescu, M.A., & Herman, E. (2020). The impact of the family background on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis. Sustainability, 12(11), 4775.

- Ghee, W.Y., Ibrahim, M.D., & Abdul-Halim, H. (2015). Family business succession planning: Unleashing the key factors of business performance. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 20(2).

- Gill, S., & Kaur, P. (2015). Family involvement in business and financial performance: A panel data analysis. Vikalpa, 40(4), 395-420.

- Gird, A., & Bagraim, J.J. (2008). The theory of planned behaviour as predictor of entrepreneurial intent amongst final-year university students. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(4), 711-724.

- Global Employment Trends for Youth (2020). Technology and the future of jobs International Labour Office – Geneva: ILO, 2020.

- Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA) (2020). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2019/20 Global Report. Available online:

- Hatak, I., Harms, R., & Fink, M. (2015). Age, job identification, and entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(1), 38–53.

- Heinonen, J., & Poikkijoki, S.A. (2006). An entrepreneurial-directed approach to entrepreneurship education: Mission impossible? Journal of Management Development, 25, 80–94. 10.1108/02621710610637981

- Herrera, J., & de las Heras-Rosas, C. (2020). Economic, non-economic and critical factors for the sustainability of family firms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 119.

- Herrero, I. (2018). How familial is family social capital? Analyzing bonding social capital in family and nonfamily firms. Family Business Review, 31(4), 441-459.

- Heuer, A., & Kolvereid, L. (2014). Education in entrepreneurship and the theory of planned behaviour. European Journal of Training and Development.

- Hoffmann, A., Junge, M., & Malchow-Møller, N. (2015). Running in the family: Parental role models in entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 44(1), 79-104.

- Hradský, O., & Sadílek, T. (2020). Motivation of generation y members working in their parents’ businesses. JEEMS Journal of East European Management Studies, 25(1), 35-54.

- Ismail, H.C., Shamsudin, F.M., & Chowdhury, M.S. (2012). An exploratory study of motivational factors on women entrepreneurship venturing in Malaysia. Business and Economic Research, 2(1), 1-13. doi:doi.10.5296/ber.v2i1.1434

- Ke, X. (2018). Succession and the transfer of social capital in Chinese family businesses: Understanding guanxi as a resource–cases, examples and firm owners in their own words. V&R unipress.

- Krejcie, & Morgan. (1970). Article “Determining sample size for research activities”. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30, 607-610).

- Kumar, A., & Kumar, P. (2013). An examination of factors influencing students’ selection of business majors using TRA framework. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 11(1), 77-105.

- Lazzarotti, V., Minelli, E.A., & Morelli, C. (2020). Socio-emotional wealth and successful generational transition in family business: the role of contextual factors. International journal of transitions and innovation systems, 6(3), 245-264.

- Lee, T. (2019). Management ties and firm performance: Influence of family governance. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 10(2), 105-118.

- Liñán, F. (2004). Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Piccolla Impresa/Small Business, 3(1), 11–35. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235937886

- Litzky, B., Winkel, D., Hance, J., & Howell, R. (2020). Entrepreneurial intentions: Personal and cultural variations. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

- Marques, F.C., Ferreira, F.A., Zopounidis, C., & Banaitis, A. (2020). A system dynamics-based approach to determinants of family business growth. Annals of Operations Research, 1-21.

- Muñoz-Bullón, F., Sanchez-Bueno, M.J., & Nordqvist, M. (2019). Growth intentions in family-based new venture teams. Management Decision.

- Newbert, S., & Craig, J.B. (2017). Moving beyond socio emotional wealth: Toward a normative theory of decision making in family business. Family Business Review, 30(4), 339-346.

- Pittino, D., Chirico, F., Henssen, B., & Broekaert, W. (2019). Does increased generational involvement foster business growth? The moderating roles of family involvement in ownership and management. European Management Review.

- Porfírio, J.A., Felício, J.A., & Carrilho, T. (2020). Family business succession: Analysis of the drivers of success based on entrepreneurship theory. Journal of Business Research, 115, 250-257.

- Pruett, M., Shinnar, R., Toney, B., Llopis, F., & Fox, J. (2009). Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: a cross?cultural study. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research.

- Quan, X. (2012). Prior experience, social network, and levels of entrepreneurial intentions. Management Research Review, 35(10), 945–957.

- Revilla, A.J., Perez-Luno, A., & Nieto, M.J. (2016). Does family involvement in management reduce the risk of business failure? The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Family Business Review, 29(4), 365-379.

- Russel, J., Jarvis, M., Roberts, C., Dwyer, D., & Putwain, D. (2003). Angles on applied psychology. Tewkesbury: Nelson Thornes.

- Sabri, N.R. (2010). MSMEs in Palestine; Challenges and potential (Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute). Ramallah, Palestine.

- Sahinidis, A., Stavroulakis, D., Kossieri, E., & Varelas, S. (2019). Entrepreneurial intention determinants among female students. The influence of role models, parents' occupation and perceived behavioral control on forming the desire to become a business owner, in Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, eds Kavoura A., Kefallonitis E., Giovanis A, 173–178. 10.1007/978-3-030-12453-3_20

- Salameh, C.S. (2017). Succession of family businesses in Palestine (Doctoral dissertation).

- Sangster, C. (2019). Family business transitions: Rising to the challenge. Co-Director, family education and governance. Northern Trust

- Shariff, M.N.M., & Saud, M.B. (2009). An attitude approach to the prediction of entrepreneurship on students at institution of higher learning in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(4), 129- 135.

- Shepherd, D.A. (2016). An emotions perspective for advancing the fields of family business and entrepreneurship: Stocks, flows, reactions, and responses

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., & Bogatyreva, K. (2016). Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. European Management Journal, 34(4), 386-399.

- Simmons, A.N. (2008). A reliable sounding board: Parent involvement in students' academic and career decision making. NACADA Journal, 28(2), 33-43.

- Sørensen, J.B. Closure and Exposure (2007). Mechanisms in the intergenerational transmission of self-employment. In the sociology of entrepreneurship; Research in the sociology of organizations; Martin, R., Lounsbury, M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK; Volume 25, pp. 83–124. ISBN 978-0-7623-1433-1. 22.

- Stafford, K., Bhargava, V., Danes, S.M., Haynes, G., & Brewton, K.E. (2010). Factors associated with long-term survival of family businesses: Duration analysis. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 31(4), 442-457.

- Tala?, E., Çelik, A.K., & Oral, I.O. (2013). The influence of demographic factors on entrepreneurial intention among undergraduate students as a career choice: The case of a Turkish university. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 3(12), 22-31.

- Tarling, C., Jones, P., & Murphy, L. (2016). Influence of early exposure to family business experience on developing entrepreneurs, Education+Training, 58(7/8). https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-03-2016-0050

- Tatoglu, E., Kule, V., & Glaister, K. (2008) Succession planning in family-owned businesses. International Small Business Journal, 26(2), 155-180.

- The World Bank (2018). Innovative private sector development report. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/479751528083037454/pdf/PAD-05152018.pdf

- Walsh, G. (2011). Family business succession managing the all-important family component KPMG LLP, A Canadian limited liability partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity.

- Walter, S.G., & Dohse, D. (2012). Why mode and regional context matter for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(9-10), 807-835.

- Wijaya, A., & Wijaya, B. (2019). The effects of integrity, entrepreneurship, knowledge, leadership to succession in first generation family business. In 16th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2019). Atlantis Press.

- Workman, J.L. (2015). Parental influence on exploratory students' college choice, major, and career decision making. College Student Journal, 49(1), 23-30.

- World Bank, (2020). Small and medium enterprises. finance. Improving SMEs’ access to finance and finding innovative solutions to unlock sources of capital. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance.

- Agbim, K.C.J.J.O.E., Management, & innovation. (2019). Social networking and the family business performance: A conceptual consideration, 15(1), 83-122.

- Ahmadi, Z.M., Nikmaram, S., & Latifi, M.J.I.J.O.M.S. (2014). Impact of family business characteristics on succession planning: A case study in Tehran industrial towns, 7(2), 243-257.

- Alves, C.A., Gama, A.P.M., Augusto, M.J.J.O.S.B., & Development, E. (2020). Family influence and firm performance: The mediating role of stewardship.

- Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W.J.P.B. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach, 103(3), 411.

- Babson, C. (2021). website. www.babson.edu.

- Bae, T.J., Qian, S., Miao, C., Fiet, J.O.J.E.T., & Practice. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review, 38(2), 217-254.

- Bagozzi, R.P., & Yi, Y.J.J. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models, 40(1), 8-34.

- Betáková, J., Havierniková, K., Okr?glicka, M., Mynarzova, M., & Magda, R. (2020). The role of universities in supporting entrepreneurial intentions of students toward sustainable entrepreneurship.

- Boso, N., Story, V.M., & Cadogan, J.W.J.J. (2013). Entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation, network ties, and performance: Study of entrepreneurial firms in a developing economy, 28(6), 708-727.

- Boyd, B., Royer, S., Pei, R., & Zhang, X.J.J. (2015). Knowledge transfer in family business successions.

- Calabrò, A. (2019). STEP2019 Global Family Business Survey - REPORT The impact of changing demographics on family business succession planning and governance. research gate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336923219.

- Carlock, R.S., & Ward, J.L. (2010). When family businesses are best: Springer.

- Carsrud, A.L., Renko-Dolan, M., & Brännback, M. (2018). Understanding entrepreneurial leadership: Who leads a venture does matter. In Research Handbook on Entrepreneurship and Leadership: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Chin, W.W.J.M. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling, 295(2), 295-336.

- Chuairuang, S. (2013). Relational networks and family firm capital structure in Thailand: Theory and practice. Umeå universitet,

- Cie?lik, J., van Stel, A.J.J., & Development, E. (2017). Explaining university students’ career path intentions from their current entrepreneurial exposure.

- Cruz, C., Justo, R., & De Castro, J.O.J.J. (2012). Does family employment enhance MSEs performance? Integrating socioemotional wealth and family embeddedness perspectives, 27(1), 62-76.

- Danes, S.M., Stafford, K., Haynes, G., & Amarapurkar, S.S.J.F.B.R. (2009). Family capital of family firms: Bridging human, social, and financial capital, 22(3), 199-215.

- De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Kotlar, J., Petruzzelli, A.M., & Wright, M.J.A. (2016). Innovation through tradition: Lessons from innovative family businesses and directions for future research, 30(1), 93-116.

- Dyer Jr, W.G., & Dyer, W.J.J.F.B.R. (2009). Putting the family into family business research, 22(3), 216-219.

- Elfarra, M. (2017). Entrepreneurship development in Palestine: An Empirical Study on the Gaza Strip.

- FBM, F.B.M. (2019). FOX family office benchmarking report, . https://www.familybusinessmagazine.com.

- FBM, F.B.M. (2020). Family business: Education: Good practices in family well-being: Embracing the rising generation. https://www.familybusinessmagazine.com/article-category/family-business-education, last seen 4/2/2021.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. In: Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

- Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M.J.J., & Practice. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet, 19(2), 139-152.

- Hair Jr,J.F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V.G.J.E. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research.

- Hart, M., Bonner, K., Prashar, N., Ri, A., Levie, J., & Mwaura, S. (2020). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: United Kingdom 2019 Monitoring Report.

- Harvey, M., Cosier, R.A., Novicevic, M.M.J.J., & Entrepreneurship. (1998). Conflict in family business: Make it work to your advantage, 10(2), 61.

- Herman, E., & Stefanescu, D.J.E.S. (2017). Can higher education stimulate entrepreneurial intentions among engineering and business students? 43(3), 312-327.

- Higginson, N.J.J., & research, M. (2010). Preparing the next generation for the family business: Relational factors and knowledge transfer in mother-to-daughter succession, 4, 1.

- Holt, D.T., & Pearson, A.W.J.W.E. (2015). Family–Power, Experience, and Culture (F?PEC) Scale, 1-3.

- Huarng, K.H., Mas-Tur, A., & Yu, T.H.K.J.I.E. (2012). Factors affecting the success of women entrepreneurs. Journal, M 8(4), 487-497.

- Hughes Jr, J.E., Massenzio, S.E., & Whitaker, K. (2014). The voice of the rising generation: Family wealth and wisdom: John Wiley & Sons.

- Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J.G., & Rau, S.B.J.J. (2015). Entrepreneurial legacy: Toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship, 30(1), 29-49.

- Klein, S.B., Astrachan, J.H., Smyrnios, K.X.J.E. (2005). The F–PEC scale of family influence: Construction, validation, and further implication for theory, 29(3), 321-339.

- Kongolo, M.J.A. (2010). Job creation versus job shedding and the role of SMEs in economic development, 4(11), 2288-2295.

- Krueger, N.F. (2007). The cognitive infrastructure of opportunity emergence. In Entrepreneurship, Springer, 185-206,

- Lacy, P., Haines, A., & Hayward, R.J.J. (2012). Developing strategies and leaders to succeed in a new era of sustainability: Findings and insights from the United Nations Global Compact?Accenture CEO Study.

- Le Breton–Miller, I., Miller, D., Steier, L.P.J.E. (2004). Toward an integrative model of effective FOB succession. 28(4), 305-328.

- Lubatkin, M.H., Schulze, W.S., Ling, Y., Dino, R.N.J.J. (2005). The effects of parental altruism on the governance of family?managed firms. Occupational, Psychology, O., & Behavior, 26(3), 313-330.

- Marja?ski, A., Su?kowski, ?.J.E.B. (2019). The evolution of family entrepreneurship in Poland: Main findings based on surveys and interviews from 2009-2018. Review, 7(1), 95-116.

- Mazzi, C.J.J. (2011). Family business and financial performance: Current state of knowledge and future research challenges 2(3), 166-181.

- Mussolino, D., Cicellin, M., Iacono, M.P., Consiglio, S., & Martinez, M.J.J. (2019). Daughters’ self-positioning in family business succession: A narrative inquiry, 10(2), 72-86.

- Neubauer, F., & Lank, A.G. (2016). The family business: Its governance for sustainability: Springer.

- Nguyen, C.J.J. (2018). Demographic factors, family background and prior self-employment on entrepreneurial intention-Vietnamese business students are different: why? 8(1), 1-17.

- Orford, J., Wood, E., Fisher, C., Herrington, M., & Segal, N.J.S.A. (2003). Global entrepreneurship monitor.

- PCBS. (2020, 18/3/2021). (PCBS, 2020): On the occasion of the international youth day, 12/08/2020 On the occasion of the International Youth Day, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) issues a press release demonstrating the situation of youth in the Palestinian society.

- Peng, Z., Lu, G., & Kang, H.J.C. (2013). Entrepreneurial intentions and its influencing factors: A survey of the university students in Xi’an China, 3(08), 95.

- Peterson, R.A., & Kim, Y.J.J. (2013). On the relationship between coefficient alpha and composite reliability, 98(1), 194.

- Sáez-Martínez, F.J., González-Moreno, Á., & Hogan, T.J.E.E. (2014). The role of the University in eco-entrepreneurship: Evidence from the Eurobarometer Survey on Attitudes of European Entrepreneurs towards Eco-innovation. Journal, M, 13(10), 2541-2541.

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M., Smith, D., Reams, R., & Hair Jr.J.F.J.J. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers, 5(1), 105-115.

- Schröder, E., Schmitt-Rodermund, E., & Arnaud, N.J.F.B.R. (2011). Career choice intentions of adolescents with a family business background, 24(4), 305-321.

- Schwass, J., & Glemser, A.C. (2016). Family Business Identity. In Wise Family Business, Springer, 7-29.

- Shapero, A.J.P.T. (1975). The displaced, uncomfortable entrepreneur, 9(6), 83-88.

- Sharma, P., Chrisman, J.J., & Gersick, K.E. (2012). 25 years of family business review: Reflections on the past and perspectives for the future. In: Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

- Shen, N.J.C.C., & Management, S. (2018). Family business, transgenerational succession and diversification strategy.

- Shi, H.X., Shepherd, D.M., Schmidts, T.J.I.J. & Research. (2015). Social capital in entrepreneurial family businesses: The role of trust.

- Sieger, C.S., Cobben, M.M., & Hovestadt, T.J.R.E.C. (2019). Environmental change and variability influence niche evolution of isolated natural populations, 19(7), 1999-2011.

- Sieger, P., Fueglistaller, U., Zellweger, T., & Braun, I.J.G.G.R. (2018). Global Student Entrepreneurship 2018: Insights From 54 Countries. St. Gallen/Bern: KMU-HSG/IMU. 3.

- Sieger, P., & Monsen, E.J.J. (2015). Founder, academic, or employee? A nuanced study of career choice intentions, 53, 30-57.

- Sigel, I.E., McGillicuddy-DeLisi, A.V., & Goodnow, J.J. (2014). Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children: Psychology Press.

- Sorenson, R.L., & Bierman, L.J.F.B.R. (2009). Family capital, family business, and free enterprise, 22(3), 193-195.

- Tagiuri, R., & Davis, J.J.F.B. (1996). Bivalent attributes of the family firm, 9(2), 199-208.

- Uma, S., & Roger, B.J.C.P.T.S. (2013). Research Methods for Business (ed.).

- Wahjono, S.I., Idrus, S., & Nirbito, J.J.J. (2014). Succession planning as an economic education to improve family business performance in East Java Province of Indonesia. 4(11), 649.

- Walter, S.G., & Block, J.H.J.J. (2016). Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective, 31(2), 216-233.

- Wang, D., Wang, L., Chen, L.J.I.E., & Journal, M. (2018). Unlocking the influence of family business exposure on entrepreneurial intentions, 14(4), 951-974.

- WB, W.B. (2018). Measuring and analyzing the tech startup ecosystem in the West Bank and Gaza. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/715581526049753145/pdf/126144-replacement-WBG-ecosystem-mapping-digital.pdf, 42.

- WB, W.B. (2021). International labour organization, ILOSTAT database. Data retrieved on January 29, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS.

- Zellweger, T., Sieger, P., & Halter, F.J.J. (2011). Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. 26(5), 521-536.

- Zellweger, T.M., Chrisman, J.J., Chua, J.H., & Steier, L.P. (2019). Social structures, social relationships, and family firms. In: Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

- Zhang, Y., Duysters, G., Cloodt, M.J.I. (2014). The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intention. Journal, m, 10(3), 623-641.

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S.E., & Hills, G.E.J.J. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions, 90(6), 1265.