Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1

Urgency of Protection of Communal Rights of the Community of Yogyakarta Central Java on the Copyright of the Traditional Architecture Works Reviewed Under Law Number 28 of 2014 Regarding Copyright

Christine S.T Kansil, Tarumanagara University

Abdul Gani Abdullah, Tarumanagara University

Simona Bustani, Tarumanagara University

Keywords

Copyright, The Traditional Architecture, Traditional Cultural Expressions

Abstract

Protection of communal rights to traditional architectural work is important in the era of globalization. Traditional architectural work is part of the creative economy. However, the regime of copyright law has not been able to protect such matter. Traditional architecture, which is a communal right of the Yogyakarta indigenous people in the Central Java Region, has not been fully protected in the copyright law. This reasearch is a normative research which is using secondary data and primary data, such as legislation and cultural approach, to be analyzed qualitatively. Protection of traditional architecture is protected in Article 38 of Law No. 28 of 2014 about Copyright. However, the protection is inadequate. The government should have made a separate regulation that protects Joglo's architectural work with a sui generis system with three protections, namely positive protection, defensive protection and causic protection.

Introduction

Preamble

The creative industry is an industry that originates from the use of creativity, skills and individual talents to create prosperity and employment by generating and exploiting the individual's creativity. This opinion is in line with the opinion of (Hartley, 2004) who said that the creative industry is an industry that accommodates traditional creative talents in the fields of design, performance, production and writing. The creative industry combines all this with the production of new media and distribution techniques and interactive technologies with the aim of creating and distributing creative content throughout the service sector of the new economy. The creative industries in Europe are known as the culture industry.1 In Indonesia the creative industry mapped creative industries covering fields, including: advertising, architecture, the art market, crafts, design, fashion, video, film, photography, interactive games, music, performing arts, publishing and printing, computer services, software, television, radio, research and culinary

Indonesia as a country that has ethnic and cultural diversity, needs to pay attention to the diversity of its traditional cultural expressions which include all objects of copyright including architectural works. Therefore, traditional copyrighted works including traditional architects have become one of the assets for creative industries in Indonesia. However, so far the copyright law has not been able to protect the creative works of traditional cultural expressions. In the field of traditional architecture, there has been a violation of Balinese architectural works that were used as a hotel architecture in USA as reported by the Ambassador.

owever, this matter was not resolved legally or diplomatically. This attitude for not being able to overcome the violation of traditional Balinese architectural works occurs because of the preveious Copyright Law was not yet able to accommodate such matter. However, the elaboration in Article 38 of Law No. Copyright 28 of 2014 ("UUHC") is inconsistente by only regulating that traditional cultural expressions are controlled by the state and their management is in the interest of the nation (Jened, 2007).2 However, the difference of values between the UUHC and the values that live in indigenous peoples have resulted in many obstacles in implementing UUHC when protecting traditional architecture. Although, in Article 38 the UUHC has tried to accommodate communal values. However, it still has not reached out to protect traditional cultural expressions effectively.

The obstacle of changing the legal culture of indigenous peoples patterned in their concept of life. It is necessary for government efforts to close the existing gaps, by preparing legal protection measures that are in accordance with the legal culture of indigenous peoples. This condition is because the work of expression of traditional culture is gradually disappearing if it is protected within the framework of copyright law. This can be occur because of the conflict of legal culture that comes from a philosophical difference between traditional cultural expressions and the copyright law regime. Therefore, a fundamental problem arises, how should a proper protection for traditional cultural expressions held by Indigenous people? This difference in concepts raises quite profound implications and creates a complicated problem in protecting traditional knowledge, so further studies are needed to anticipate violations of traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions of indigenous peoples.

Research Question

Traditional architecture which is a communal right of the Yogyakarta indigenous people in the Central Java Region has not been fully protected in the copyright law.

Research Method

In this research, the most appropriate type of normative research is to use a legislative approach and cultural approach. This type of research focuses on the study of literature which means that it will examine the primary legal material, namely UUHC. In addition, it uses secondary legal materials that discuss culture within the framework of copyright law in protecting traditional architectural works. Article 38, Article 40, Article 58 of the UUHC is the main concern as they emphasize the concept of traditional cultural expression. Furthermore, it uses the cultural approach of the Yogyakarta Central Java community which is related to sacred and religious values.

This research study aims to fill the shortfall of copyright law related to communal values that live in indigenous peoples, so that they can inspire and reflect local legal material on Indonesian copyright law.3 In this study, a qualitative analysis method was chosen considering that the data analyzed were diverse and had conflicting value concepts. The other reason is because qualitative data processing is more flexible and clearly describe the flow of data analysis obtained more in depth and thoroughly from various aspects, so that it is a unified whole.4

Methodology (Literature Review)

The Communal Concept in the Legal Protection of Traditional Architecture

Legal Protection of Traditional Architecture

Under UUHC, copyright is an exclusive right for the creator and the rights holders include moral rights and economic rights.5 The creator is the person who creates the work that has the character and characteristics of the creator, while the copyright holder is the party who further accepts the right from the creator rather than the creator of the copyrighted work.

Indigenous people are people who have high creativity related to the moral and sacred values and beliefs. Therefore, at this time communal rights of indigenous people should be given legal protection for their traditional culture. It is important to stop degrading the value of the sacredness of a work for commercial purposes. The reason is because indigenous people can be grouped as simple people whose lives are generally based on customary law and norms that are enforced through informal social sanctions.6

In Article 40 letter h UUHC regulates the scope of protected works and architectural works, which in the explanation referred to as architectural works, among others, the physical form of buildings, structuring the layout of buildings, technical drawings of buildings and models or models of buildings. Architectural works need to pay attention to the characteristics of the protected work, which is to fulfill the characteristics of originality, whereas the work must be original born from the creator and the work must be fixed in a form.7

The Consideration of UUHC does not include the protection of communal rights of indigenous peoples. the UUHC is a emphasize individual concept as seen from the underlying legal basis is Article 28 C of the 1945 Constitution.8 In the UUHC, there is not a single government legal politics in the field of copyright that gives reasons for the importance of protecting communal rights of indigenous peoples related to traditional cultural expression works. In Article 38 paragraph 3 of UUHC, there is a sentence that states that "considering to the values that live in the carrier community".9 It can be said that cultural wealth which is the raw material for the birth of traditional cultural expression works, is not important to note, even though Indonesia has ethnic and cultural diversity which consists of 20,000 islands, where each island has customs, customs, as well as cultural diversity in accordance with his characteristics.10

The cultural diversity is clearly seen in geographical, ethnic, socio-cultural, religious and belief aspects. However, the weakness of government legal politics in the field of copyright, the latest is the copyright regulation as seen in Article 38 of the UUHC, is predicted to create greater obstacles compared to previous copyright regulations. This weakness is a result from the Copyright Law for not functioning perfectly, so that legal vacancies continue to occur, despite changes in copyright laws. This can be seen from the sum of the provisions of Article 38 of the UUHC, resulting in these articles not being applicable to cases related to violations of traditional cultural expression works. In Indonesia, the ratification of this convention is ratified by Law No. 5 of 1994 concerning Ratification of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, abbreviated as CBD.

Based on CBD, it can be seen that traditional knowledge is divided into 3 (three) groups, namely the work of traditional cultural expressions, geographical indications and biodiversity which includes genetic resources and traditional knowledge. So based on this CBD, it can be an international legal basis for protecting traditional cultural expressions including traditional architecture, such as the pendopo which is an interior architecture and other parts that are a unified whole.

Traditional Architecture Works and the Diversity of Local Culture and Violations of Architectural Works

Traditional architecture has a harmonic proportion of religious values in a physical form that is displayed in a sacred manner and has philosophical values that have certain magical powers. 11 Therefore, architecture as the realization of ideas is always associated with expressions which of course have suppressed the function and rhythmic composition of mass. 12 Architecture is the lowest art because architecture uses a lot of materials and is a three-dimensional space art, but uses space and emphasizes on space.13 Javanese buildings are based on the thoughts of Javanese architects of their time. Their work is related to the circumstances and harmony of society with nature. Therefore, the data said that the structure and structure of architecture has a range of cultural, religious, political values and some dimensions that show a touch of aesthetic value as a summary of the architect's creative ideas.14

The building is also equipped with a Pawon or kitchen.15 The direction of the house makes it easier for Javanese to know directions. Someone who comes out of the house is heading towards the south, while praying means the left side is north. So that they are very integrated with the surrounding environment and the benchmark is angina eyes.16

Minto Budoyo classifying five types of roofs as the basic form of Javanese buildings; panggang pe, kampong, limasan, joglo and tajug. Panggang pe is usually used for temporary housing, usually drying the harvest and usually the shape is close to the square and tilted to one side. The village is also called serotong, considered to be a simple permanent residence. Joglo stands for tajug and loro or the merger of two tajug roofs into one. Joglo can only be built by rich people. This situation makes building preparation easy because materials can be done in the field, when everything is available, so that the building can be built quickly.17

Magersari was originally a land use system whose workers were not entitled to land and building rights (Wijomartono et al,. 2009).18 The order of the building layout of the Yogyakarta and Surakarta palaces arranged on the north and south axis with the north and south squares as an end and three rows of gates and courtyards to the north and south starting from Ageng Tengah Pavilion is a description of Jawadwipa, the central land in the picture the Javanese universe first. 19 Even like an uninhabited house accompanied by no furniture, it suggests that there is no sign of life (Abdul, 2012).20

Analysis of the Protection of Communal Rights of the Yogyakarta Indigenous Peoples in the Central Java Region against the Traditional Architecture Work

Architectural works are works that are protected by copyright law, as individual works that are attached to copyright as in Article 40 letter h UUHC and their explanations, which include the protection of moral rights and economic rights. The existence of the joglo building is a traditional Central Javanese house that intersects with noble values. So that it can be said that joglo building is not just a residence. More than that, it is a symbol, a reflection of values, norms of society, a sense of beauty and even religious values.21 The most important part of this Javanese house is the closed joglo which is a sacred joglo, where the center is a soko guru which is the center of the 4 pillars. The middle part is called the place of the goddess Sri who is in the middle. On the left side of this closed joglo is the room of the king or sultan and his right room is the mother of the queen (the king's mother). After that it will be separated by pringgitan which sometimes the roof is often less semestric which has a leaky impact on the technical aspects of the architecture. In the front there is an open joglo known as the pavilion. 22 Now, those who are not nobles but wealthy can just build these elegant and classic homes. 23

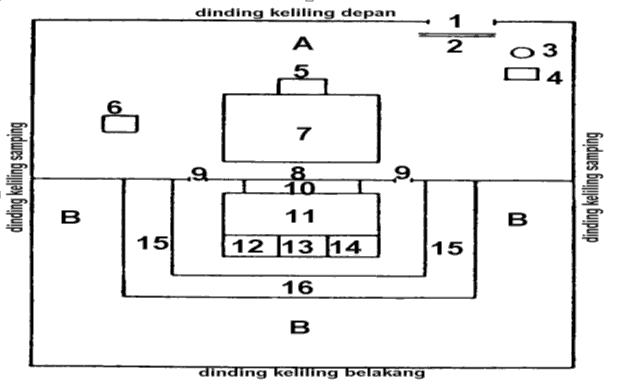

The schematic image of the joglo building in figure 1 is presented as follows: 24.

Caption :

A. Front Yard:

1. Regol, 2. Rana, 3. Lifespan, 4. Breaking, 5. Kuncung, 6. Horse cage, 7. Pendopo

B. The inside yard is divided into:

8. Longkonan, 9. Seketheng, 10. Pringgitan, 11. Dalem, 12. Senthong Kiwa (left), 13. Middle Sentong (right), 14. Right wing, 15. Ganchok, 16. Kitchenr and others.

Andersen's theory of collectivist culture that emphasizes community, collaboration, interest, harmony, tradition, public facilities, and ways of maintaining self-esteem, is very different from individualistic cultures that emphasize personal rights and obligations and privacy.25 Unity which is built on the basis of shared interests that value the sanctity of giving birth to social rites. Society supports itself by moving from and to the sacred which is formed by ceremonies, festivals and other cultural events called Ritus. Ritus are held collectively and regularly so that the community is refreshed by collective knowledge and meanings. This gives a Javanese view of the cosmos and its fellow conflict.26

Considering the sacred values inherent in the joglo building, the joglo building can be categorized as a work of traditional cultural expressions as regulated in Chapter V of Part One of Article 38 which consists of 4 paragraph of UUHC. Traditional architectural works, especially Joglo architecture, should be protected by communal rights because they are works owned by the Jogjakarta indigenous people. Therefore, joglo buildings should be categorized as traditional cultural expressions. It is necessary to pay attention to the values that live in the adat community with regards to the process of making and utilizing them. As in Article 38 paragraphs 3 of UUHC which is stating that "considering to the values that live in the bearer community". The Explanation of Article 38 paragraph 3 of UUHC concerning Copyright explains that: what is meant by "living values carrier communities are customs, customary norms, social norms and other noble norms that are highly upheld by the communities of origin, who maintain, carry and preserve traditional cultural expressions."

Government Efforts to Anticipate the Protection of Communal Rights of Yogyakarta Central Java Indigenous Peoples against Traditional Architecture Works in the UUHC Regime.

Related to the protection of traditional cultural expressions, supplemented by Minister of Education and Culture Regulation No. 106 of 2013 regarding the Non-Objects Cultural Heritage of Indonesia. This Ministerial Regulation aims to provide an obligation to the Government to carry out the recording and stipulation of Non-Objects Cultural Heritage of Indonesia. In the Ministerial Regulation, the definition of Non-Objects Cultural Heritage of Indonesia is "the various results of the practice of realization, the expression of knowledge and skills related to the cultural sphere that is passed on from generation to generation culture that is intangible after going through the process of determining intangible objects". Furthermore, what is said to be "intangible cultural heritage consists of oral traditions and expressions, performing arts, rites of community customs and celebrations, knowledge and behavioral habits of recognizing nature and the universe and or skills and skills of traditional crafts."

The defensive protection approach refers to efforts to prevent the taking of traditional knowledge works including cultural heritage expressions by parties who have no right to use according to local customs, for example by collecting data in a data base. Meanwhile, a positive approach refers to the mechanism of contracting or the use of an IPR system or sui generis protection to ensure protection that is appropriate for traditional knowledge owners or managers including the expression of the cultural heritage.27 In this case, there is a need for government efforts to determine the right approach in protecting traditional, sacred architectural works. 28

Although currently there are regions that have regulations governing traditional architectural works such as Bali, namely Badung Regent Bali Regulation No. 1 of 2008 regarding Hotel Condos and Denpasar Mayor Regulation No. 42 of 2007 concerning Condominium hotel buildings related to the obligation to use Balinese architecture in hotel buildings and condo. Meanwhile in Yogyakarta, there are Yogyakarta Regional Provincial Regulations Number 6 of 2012 regarding Preservation of Culture and Nature Reserves but in it discusses the position of the palace regarding its natural position. However, this regulation does not specifically address the protection of joglo architectural works which are full of sacred values as it only discusses the regular position of the four corners of the wind.29 This can be seen from the philosophical axis and imaginary axis described in the picture i.e, figure 2 below:

Information:

Philosophy Axis

Tugu Pal Putih - Kraton - Panggung Krapyak

IMAJINER AXIS

Mount Merapi - Kraton - South Sea

In the Appendix of this Regulation, it is explained that the description of Appendix A: Judging from the spatial layout, DIY is specially arranged by Sri Sultan Hamengku Buwono I with a high concept and full of meaning visualized in Cultural Heritage which includes Mount Merapi-Kraton Selatan Laut (Samudra Indonesia). This Cultural Heritage describes the Imaginary Axis that is in harmony with the concepts of Tri Hita Karana and Tri Angga (Parahyangan – Pawongan – Palemahan or Hulu – Tengah – Hilir and the Main values – Madya-Nistha). Philosophically this imaginary axis symbolizes harmony and balance of human relations with the God of man and man with nature which includes the five formers of fire (dahana) from Mount Merapi, land (bantala) from Ngayogyakarta earth, and water (tirta) from the South sea, wind (maruta) and space (eiter). Similarly, when viewed from the concept of Tri Hita Karana, there are three elements that make life (physical, energy, and soul) covered in the philosophy of the imaginary axis.30

Meanwhile, from Tugu Golong-Gilig/Pal Putih to the south symbolizes the human journey to face the Creator. The features of the DIY location are inseparable from the location of the Yogyakarta Palace, which is in a purified area because it is flanked by 6 (six) rivers symmetrically namely Code River, Gajah Wong River and Opak River on the east side, and Winongo River, Bedhog River and Progo River in the west side, Mount Merapi on the north and South Sea (Indonesian ocean) on the south side. The midpoint of the philosophical axis of the Governor of the Special Region of Yogyakarta, Hamengku Buwono X vertical axis of the road.31 Another strategy implemented by the Central Government with the Regional Government is the plan of the Directorate General of Culture to unite in the form of twin cities, namely Yogyakarta and Surakarta including preserving traditional architectural works in the concept of recognition at the international level through UNESCO as a human heritage in the world. 32

Conclusion

a). Joglo's architectural work is a traditional masterpiece that is loaded with sacred values. So that joglo buildings can be grouped in traditional cultural expressions arranged in Article 38 UUHC. Therefore, special regulations are needed to regulate sacred traditional architectural works including joglo buildings as indigenous peoples cultural identities and macro national identities, because sacred traditional architectural works cannot be replicated without going through rituals provided that they do not inhibit the development of creative creativity architecture.

b). The current government strategy is inappropriate because there is no separate regulation to regulate the protection and preservation of joglo building architecture from an element of art. Yogyakarta Regulations that there are only regulations regarding the geographical position of the palace which is regulated in Yogyakarta Regional Province Regulation Number 6 of 2012 concerning Cultural Conservation and Nature Reserves. The government should be able to regulate itself with a sui generis system that can choose three protections, namely positive protection, defensive protection and causic protection.

Recommendation

a). The Central Government together with the Regional Governments need to work together to make legal regulations regarding the protection of traditional sacred architectural works which include traditional cultural expressions such as joglo buildings through a positive protection approach, casuistic protection and defensive protection with a sui generis system.

b). There are needs of concrete action from the government to empower indigenous people through assistance and also prepare various tools with the nature of facilities and infrastructure so that the regulation can be implemented optimally and be effective in protecting the communal rights of indigenous peoples over traditional architectural works such as this joglo building.

Ethical Issue

Authors are aware of, and comply with, best practice in publication ethics specifically with regard to authorship (avoidance of guest authorship), dual submission, and manipulation of figures, competing interests and compliance with policies on research ethics. Authors adhere to publication requirements that submitted work is original and has not been published elsewhere in any language.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that would prejudice the impartiality of this scientific work.

Authors’ Contribution

All authors of this study have a complete contribution for data collection, data analyses and manuscript writing.

End Notes

- John Harley, Communication culture & media studies, (London: Routledge, 2004), 118.

- Rahmi Jened, Hak Kekayaan Intelektual, Penyalahgunaan Hak Eksklusif, (Surabaya: Airlangga University Press, 2007), 56-57.

- Ibid, h 315 dan h 318.

- Check and compare, Burhan Bungin, Analisis Data Penelitian Kualitatif, Pemahaman Filosofis dan Metodelogis kearah Penguasaan Model Aplikasi, (Jakarta: RajaGrafindo, 2003) h 83-84.

- Article 1 number 1 and Article 4 Copyright Law 2014 the definition of copyright is “exclusive rights that arise automatically based on the declarative principle after a copyright is manifested in the tangible form without reducing restrictions in accordance with the provisions of statutory regulations.”

- Cita Citrawinda, Budaya Hukum Indonesia Menghadapi Globalisasi, Perlindungan Rahasia Dagang Di Bidang Farmasi, (Jakarta: Chandra Pratama, 1999), h 201.

- Traditional architectural works related to traditional cultural expressions contained in Chapter V Part One Article 38 which consist of 4 act of Law Number 28 of 2014 concerning Copyright, which contain:

(1).The Copyright on Expressions of Traditional Culture is held by the State.

(2).The state must inventory, maintain and preserve traditional cultural expressions as referred to in act (1) must pay attention to the values that live in the carrier community.

(3).The use of traditional cultural expressions as referred to in act (1) must pay attention to the values that live in the carrier.

(4).Further provisions regarding copyright held by the state for traditional cultural expressions as referred to in act (1) are regulated by Government Regulation.

- Article 28 C of the Amendment to the 1945 Constitution.

- Explication of Article 38 act 3 of Law Number 28 of 2014 concerning Copyright explains that: what is meant by living values in the carrier community are customs, norms of habit, social norms and other noble norms which are respected by the community of origin who maintain, carry and preserve traditional cultural expressions.

- Indonesian Science Study Institute, Kepentingan Negara Berkembang Terhadap Hak Atas Indikasi Goegrafis Sumber Daya Genetik dan Pengetahuan Tradisional ( Depok :FHUI, 2005) h 73

- Antariksa, Pelestarian Arsitektur dan Kota yang Terpadu, (Yogyakarta: Cahaya Atma Pustaka, 2015) h 44-45

- Ibid, h 47.

- Ibid, h 56.

- Ibid, h 65 quoted Y.B Mangunwijaya, Wastu Citra Pengantar ke ilmu Budaya Bentuk Arsitek Sendi-Sendi Filasafatnya Beserta Contoh-Contoh Praktisnya, h 112.

- Bagoes Wijomartono et.all, Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia, Arsitektur, (Jakarta: Rajawali Press, 2009) h 85-87.

- Ibid, h 87.

- Ibid, 80-81.

- Ibid, h 88.

- Ibid, h 88.

- Juraid Abdul Latief, Manusia Filsafat Dan Sejarah, (Jakarta ; Bumi Aksara, 2012) h 35.

- Interview result with Yuke A, Traditional Architecture Expert, Yogyakarta, April 20, 2016.

- Interview result with Yuke A, Traditional Architecture Expert, Yogyakarta, April 20, 2016.

- Tri Yuniastuti, Satrio HB Wibowo dan Sukirman “Tata Ruang Rumah Bangsawan”, Dimensi Teknik Arsitektu, Universitas Widya Mataram Yogyakarta, 30( 2), Desember 2002:h 99.

- Ibid, h A 102.

- Mulyana, D. Komunikasi Lintas Budaya. Bandung: ( Jakarta: PT Remaja Rosdakarya, 2011) h 25-26.

- Ibid, h 98 quoted Frans Magnis Suseno, Etika Jawa, (Jakarta: Gramedian 1984).

- Interview result with Henry Soelistyo Budi, Intelectual Property Rights Expert, Pelita Harapan University, Jakarta, May 3, 2016.

- Interview result with Miranda Risang Ayu, Intelectual Property Rights Expert, Padjajaran University, Bandung, April 15, 2016.

- Interview result with Ade Saptomo, Customary Law and Local Wisdom Expert, Jakarta, April 30, 2016.

- Attachment, Yogyakarta Regional Province Regulation Number 6 of 2012 concerning Cultural Conservation and Nature Reserves.

- Ibid, Attachment.

- Interview result with Yuke A, Traditional Architecture Expert, Yogyakarta, April 20, 2016.

References

- Space. (2015). Architectural conservation and an integrated city. Yogyakarta: Cahaya atma Pustaka.

- Lutviansori, A. (2010). Copyright and protection of folklore in Indonesia. Yogyakarta: Graha Ilmu.

- Rosalina, B. (2010). Protection of architectural works based on copyright. Bandung: Alumni.

- Ashshofa, B. (2004). Legal research methods. Jakarta: Rineka Cipta.

- Wijomartono, B. (2009). Indonesian cultural history, Architecture. Jakarta: Rajawali Press,

- Citrawinda, C. (1999). Indonesian legal culture in facing globalization, protection of trade secrets in the pharmaceutical sector. Jakarta: Chandra Pratama.

- Soelistyo, H. (2014). Intellectual property rights, conceptions, opinions and actualization, second book. Jakarta: Penaku.

- Harley, J. (2004). Communication culture & media studies. London: Routledge.

- Indranata, I. (2008). Qualitative approaches to quality control. Jakarta: University of Indonesia Publisher.

- Abdul, L.J. (2012). Human philosophy and history. Jakarta; Earth Literature.

- Institute for the Study of Law. (2005). Indonesia, interests of developing countries on the right to geographical indications of genetic resources and traditional knowledge; Depok : FHUI.

- Marzuki, P.M. (2006). Legal research. Jakarta: Kencana.

- Mulyana, D. (2011). Cross-cultural communication. Bandung: Jakarta: PT Pemuda Rosdakarya.

- Rahmi, J. (2007). Intellectual property rights, abuse of exclusive rights. Surabaya: Airlangga University Press.

- Soerjono, S., & Mamuji, S. (2006). Normative legal research a brief overview. Jakarta: RajaGrafindo Persada.

- Lindsey, T. (2002). Intellectual property rights an introduction. Bandung: Alumni.

- Yuniastuti, T., Wibowo, S.H.B., & Sukirman, D. (2002). “The spatial planning of the noble house”. Dimensions of architectural engineering, Widya Mataram University Yogyakarta, 30(2).

- CBD Ad-Hoc open- ended working group on acces and benefit sharing, report on the role of intellectual property right in the implementation of acces and benefit- sharing ararrangements (UNEP/CBD/WG-ABS/1/4,)

- Indonesian Law Number 28. Copy Right 2014.

- Regulation of the minister of education and culture number 106 concerning Indonesia’s intangible cultural heritage 2013.