Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Work-Life Balance Policies and Job Satisfaction

Wahda, University of Hasanuddin

Almaida, University of Hasanuddin

Nurqomar, I.F, University of Hasanuddin

Keywords

Social Exchange Theory, Job Satisfaction, Work-Life Balance Policies

Abstract

To get employees' best performance, organizations need to create a working environment that can bring satisfaction to their employees. The Work-Life Balance (WLB) policy is a crucial policy intended to help employees balance their work and lives to achieve job satisfaction. This research aims to evaluate the effectiveness of WLB policies implementation in the workplace in Makassar city. The focus is on the impact of this program on job satisfaction at the workplace. The research model was tested quantitatively through a field survey. A total of 200 completed questionnaires from five private organizations and four from government organizations are reported and statistically analyzed using multiple linear regression analysis with SPSS 23 (Statistical Product and Service Solutions). Furthermore, this study used the Bivariate correlation and Cronbach Alpha to test the construct validity and reliability of the measurement items. Contrary to most studies, the data analysis results revealed that the WLB policy's implementation does not directly lead to increased employees' job satisfaction. In the Makassar context, certain policies have the opposite result. The result showed that the reasons for impact variations in WLB policies implementation are not just cultural factors; social factor (e.g., ostracism or stigmatization) is other factors that must be a concern.

Introduction

Due to the fast-paced organizational development in recent years, practitioners and authors in management have continually acknowledged the value of human capital as a means of competitive advantage. Therefore, for organizations to obtain the best employee performance, they need to create a friendly working environment to provide satisfaction to their employees. Employees satisfied with their job will positively contribute to organizational performance (Ostroff, 1992; Ryan, Schmitt & Johnson, 1996; Schneider et al., 2003). Thus examining factors determining employees' job satisfaction is of great interest (Calvo-Salguero, Lecea & Gonzalez, 2011). However, according to Devi & Rani (2016), work demands are increasingly time and energy-consuming to productivity, thereby causing stress and an imbalance between work and family life, with a decrease in job satisfaction.

There are two most critical domains of human life: job and family (Clark, 2000; Voydanoff, 2005), and they are capable of causing conflict (Frone et al., 1992; Allen, Herst, Bruck & Sutton, 2000). Role conflict is characterized as the appearance of two or more pressures while making fulfillment of one role render fulfillment with the other more challenging (Kahn et al., 1964). Many types of work-family conflict studies have demonstrated detrimental work-related impacts such as job dissatisfaction (Kossek & Ozeki, 1998) and intention to move (Netemeyer, Boles & McMurrian, 1996) and stress/tension (Frone, 2000) indirectly influencing organizational competitiveness. Work-Life Balance (WLB) is the ideal form of work-family conflict. WLB is a balance between the individual's two entirely different roles: work and family, which satisfies the role holder's life (Greenhaus et al., 2003; McCarthy, Darcy & Grady, 2010; Soomro, Breitenecker & Shah, 2017). The concept of WLB is not meant to be seen as one priority scale instead as a complementary element of life as a whole (Sundaresan, 2014), and it is subjectively unique for each individual, depending on their feelings and beliefs (Kossek et al., 2014). WLB is important for both employees and organizations makes organizational support to help employees minimize the work-family conflict become increasingly desirable among practitioners and researchers.

The WLB policy is a policy initiated by the government and formal organizations to help employees manage their work and personal life (Burgess & Strachan, 2005; McCarthy, Darcy & Grady, 2010; Lee & Hong, 2011; Afrianty, 2013). It is designed to provide freedom for workers to determine when, where and how work is performed (perrigino et al., 2018). Effective implementation of WLB policy increases the sense of well-being and quality of life (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006), enhances organizational effectiveness (Eby et al., 2005), and helps organizations recruit and maintain their competent workforce for sustainable profitability.

Sat (2012) stated that Indonesian cultural values are associated with moments of being together with family, relatives, and friends. The philosophy of traditional gender roles and patriarchal culture adopted in Indonesia requires women to assume greater domestic responsibility, although women's biggest reason to work is to enhance their family welfare. Apart from these cultural factors, there is a significant increase in double-income families due to an increase in the female workforce (World Bank, 2013). The National Labor Force Survey (Sakernas) carried out by Statistics Indonesia (BPS) showed that female Labor Force Participation Rates (LFPR) reached 50.77% in August 2016, from 50.28% in August 2013. According to a Nielsen survey conducted in Indonesia, the importance of work-life balance has also garnered considerable attention and is one of the most significant issues confronting jobs, alongside financial concerns (Post, 2012). These employees want WLB benefits that allow them to work remotely and pursue personal interests, especially for female employees (Mittal, 2017).

This research was conducted in one of the big cities in Indonesia, namely Makassar. In Makassar, the number of female workers has increased by 9.3%, from 1.375.701 in February 2016 to 1.504.392 in February 2020, and contributed around 48.29% of the total workforce (BPS, 2020). The growth of the female workforce in Makassar, making WLB issue important. Despite the fact that both woman and man can experience conflict caused by an imbalance of work-life, (Apperson et al., 2002; Gurbuz, Turunc & Celik, 2013; Devi & Rani, 2016) have pointed out that work-family conflict among women is more significant than men due to limitations related to energy and time (Ahmed, 2008). It shows the relevance of exploring work and family issues by examining WLB policies' effectiveness in Indonesia. Despite the relevance of work-life issues for organizational performance and a strong case for assessing the effectiveness of WLB policies in Indonesia, research in this field remains limited (Afrianty, 2013; Afrianty, Issa & Burgess, 2015 & 2016)

Literature Review

Work-Life Balance (WLB) Policy

A Work-Life Balance (WLB) policy refers to a group of formal organizational programs and strategies to promote employees' balance of work and life (Burgess & Strachan, 2005; McCarthy, Darcy & Grady, 2010; Lee & Hong, 2011). This policy emerged as a form of organizational response to workforce demographics changes, including a growing number of dual-earner and dependent women. Nowadays, for most employee, WLB policies are highly valued because they offered psychological support to an employee as a means of organizational support (Bakker & Demorouti, 2007) and helps them cope with stress (Kossek et al., 2011). Moreover, from an organizational perspective, WLB policies decrease absenteeism and turnover rate, enhance efficiency and organizational image, and ensures retention and loyalty.

WLB policies differ between industries, organizations, and between countries, owing to the several variables that can affect their organization. From the organization's perspective, it is believed that the percentage of women in the workforce, workforce age, company size, the attributes and experiences of the top management team or top policymakers, geographical location, and a company's historical development all affected the decision to implement some of WLB policies (Afrianty, 2013). Based on literature reviews from several journals related to WLB policy, Afrianty (2013, 2015, and 2016) divided WLB policy into three main types: flexible working Hours, specialized leave options, and dependents care. Moreover, for Indonesia Context, (Afrianty, 2013) added religious support as a part of WLB policies.

Flexible working hours refer to work options that allow employees to determine when and how to complete their work (Orpen, 1981; Allen, Johnson, Kiburz & Shockley, 2012). The term is often utilized in various programs, such as compressed hours, non-standard hours, diverse remote working approaches, and reduced working hours (Kelliher & Anderson, 2010). The specialized leave options refer to numerous leave policies and working hours deductibles. Specialized leave options include bereavement leave, parental leave, paternity leave, sabbatical leave, and leave for sick family members (Bardoel, 2003). Dependent care support refers to providing social assistance to dependent workers, such as children and the elderly in the workplace (Drago & Kashian, 2003). This support includes informing employees of existing childcare providers, providing assistance through care arrangements, offering financial aid at the cost of childcare, providing funding support to employees for elderly care costs, and running an elderly center support program (Afrianty, 2013, 2015, and 2016). Religious support refers to support in line with Indonesia's laws and regulations to secure employee rights concerning religious matters (Afrianty, 2013; 2015 & 2016).

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction relates to favorable or unfavorable emotions relevant to one's work-life (Locke, 1976). It provides a rich image of employees' preferences and moods and a tool to inspire, reward, and promote business growth (Adepoju, 2017). According to Brown and Peterson (1993), this process affects the past temporal orientation and the present without affecting the future. Job satisfaction consists of the affective and cognitive elements of the individual's character. The cognitive comprise assumptions and opinions regarding the job, while the effective involves thoughts and emotions relevant to the job. Job satisfaction affects the efficiency, productivity, recruiting, participation, retention, and organizational engagement of an individual (Lu, While & Barriball, 2007). Conversely, job dissatisfaction is expressed in various ways depending on the situation: absence from work, withdrawal from work, and particular work actions (Lu, While & Barriball, 2007).

There are several job satisfaction predictors, including those from the employee (intrinsic) and those of the organization (extrinsic). These intrinsic variables include professional interest, autonomy, family demands, career advancement, and job responsibility. Meanwhile, the extrinsic values include job complexity, role uncertainty, workplace culture, skill diversity, job security, and supervisors' encouragement. The importance of employee job satisfaction for the organization makes managers involved in adopting strategies and initiatives that can increase organizational satisfaction, leading to more good work behavior (Calvo-Salguero et al., 2011).

WLB Policies and Job Satisfaction

Studies on the relation between WLB and job satisfaction have been carried out in recent years due to increased demand for WLB among employees. It aims to test the relationship between those two variables to assess the program's performance in an organization and calculate an individual's overall satisfaction level, which will indirectly affect organizational productivity. Existing research suggests that people with a work-life balance are more satisfied with their lives and report improved physical and mental well-being (Greenhaus et al., 2003; Haar, 2013; Brough et al., 2014). Thereby, providing organizational support policies to help employees balance work-personal life is assumed can increase employees' job satisfaction levels.

Social exchange theory serves as the theoretical underpinning of the relationship between these two variables (Blau, 1964). According to this theory, an exchange occurs when an individual compares the value and the cost, and they will feel obliged to display a good attitude or behavior when they realize that their preference has been satisfied, thereby leading to more pleasurable outcomes. This theory's application to work-family interactions is that when employees believe that their organization supports them in managing work and family roles, they are more likely to feel encouraged and cared for. Therefore, they generate positive feelings towards work (McNall et al., 2009) and likely experience job satisfaction (Blau, 1964; Birtch et al., 2015; Kalliath, 2020). Therefore, in conclusion, the implementation of work-life balance policies -that comprise flexible working hours, specialized leave options, dependent care support, and religious support- aims to assist employees in balancing their work-life roles, which leads to more positive work attitudes and behaviors among employees due to the direct benefits obtained from the policies.

Research Methodology

Research Design

This research is descriptive and cross-sectional research carried out from July 2020 to September 2020. Primary data sources were collected through a survey method with a questionnaire to collect data personally administered to the respondents. The purposive sampling method was used to obtain data from 200 samples of women from four government and five private organizations.

Questionnaire and Measurement Method

The study operationalized five variables: Flexible work, specialized leave option, dependent care support, religious support, and Job Satisfaction (JS). Four variables of WLB policies measurement were adapted from Afrianty (2013). The respondents were requested to indicate their current WLB policy or what they had used previously. The unavailable program was coded 0, available but never used coded 1, while available and already using used coded 2. For the JS variable, the research questionnaire was adapted from Michigan Organisational Assessment Questionnaire (Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins & Klesh, 1983) using five point-Likert scales starting from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree.

The obtained data analyzed with SPSS (Statistical Product and Services Solution) version 23 hereinafter tested using the Multiple Linear Regression equation. Furthermore, multiple linear regression was used to examine the impact of flexible work, specialized leave option, dependent care support, and religious support on JS. This research used validity and reliability testing.

Conceptualization and Hypothesis Development

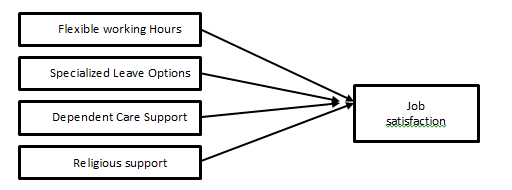

Figure 1 below shows the relationship between variables. WLB Policies that comprise: flexible working Hours, specialized leave options, dependents care, and religious support are the independent variable, whereas job satisfaction is the dependent variable.

Finding and Discussion

Finding

Test of Validity and Reliability

Table 1 indicates the validity test result, which is aimed at assessing the accuracy of the measurement. In assessing validity, the statement item is associated with the total item (total score). When the value of the corrected item-total correlation is less than 0.30, an item is considered valid.

| Table 1 Result of Validity And Reliability Test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Indicator | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach's Alpha |

| 1. | Flexible Work | 0.758 | |

| X1.1 | 0.802 | ||

| X1.2 | 0.802 | ||

| X1.3 | 0.707 | ||

| X1.4 | 0.743 | ||

| 2. | Specialized Leave Option | 0.623 | |

| X2.1 | 0.455 | ||

| X2.2 | 0.558 | ||

| X2.3 | 0.590 | ||

| X2.4 | 0.499 | ||

| 3. | Dependent Care Support | 0.680 | |

| X3.1 | 0.455 | ||

| X3.2 | 0.952 | ||

| 4. | Religious support | 0.667 | |

| X4.1 | 0.489 | ||

| X4.2 | 0.927 | ||

| 5. | Job Satisfaction | 0.637 | |

| Y.1 | 0.645 | ||

| Y.2 | 0.272 | ||

| Y.3 | 0.708 | ||

The evaluation criteria for reliability are obtained by observing the alpha of Cronbach as a reliability coefficient. It shows how homogeneous the measurement items are and represent the same fundamental structure. When the alpha coefficient is greater than 60, it is considered reliable (Ghozali, 2009).

Table 1 shows that for all statement items representing the variable, the value of the correction item-total correlation is more than 0.30, which means the data has been deemed valid for all items of variables (Hair et al., 2011) and that the value of the Cronbach alpha is more than 0.6, making them reliable (Ghozali, 2009).

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Test

This analysis evaluates the independent variable's impact, namely flexible work, specialized leave option, dependent care support, and religious support, on the dependent variable, namely job satisfaction.

The findings obtained from the study test are shown in Table 2:

| Table 2 Result of Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Test |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 9,766 | ,648 | 15,079 | ,000 | |

| X1 | -,060 | ,037 | -,124 | -1,648 | ,101 | |

| X2 | ,024 | ,064 | ,029 | ,369 | ,712 | |

| X3 | -,082 | ,083 | -,072 | -,990 | ,323 | |

| X4 | ,110 | ,099 | ,084 | 1,106 | ,270 | |

a. Dependent Variable: Y

b. Predictors: (Constant), X4, X3, X1, X2

Based on Table 2, it obtained the following regression equation:

Y=9,766-0,060X1+0,024X2-0,082X3+0,110X4+e

From the equation above, it can be explained as the following:

1) The value of constant (α) of the equation is 9,766 and positive. It means that if the value of flexible work, specialized leave option, dependent care support, and religious support is zero, the value of job satisfaction is 9,766.

2) The value of coefficient X1 is 0,060 and negative, which shows that the flexible work variable had a negative effect on job satisfaction. When the value of flexible work increases by one unit, the value of job satisfaction decreases by 0,060 or 6%.

3) The value of coefficient X2 is 0,024 and positive. It illustrates that the specialized leave option had a positive effect on job satisfaction. When the value of the specialized leave option increases by one unit, the value of job satisfaction rises by 0,024 or 2,4%.

4) The value of coefficient X3 is 0,082 and negative, which shows that the dependent care support variable had a negative effect on job satisfaction. When the value of dependent care support increases by one unit, the value of job satisfaction will increase by 0,082 or 8,2%.

5) The value of coefficient X4 is 0,110 and positive. It explains that when the value of religious support increases by one unit, the value of job satisfaction increases by 0,110 or 11%.

Hypothesis Testing

The hypothesis testing applied in the study aimed to observe the independent variables' effect on the dependent variable. The hypothesis testing consists of F-Test (Simultaneous) and T-Test (Partial).

F-test (Simultaneous) aims to measure the influence of the independent variables together on the dependent variable. If the significance value <0.05 or f count> f table, then Ha is accepted. Vice versa, if the significance value> 0.05 and the calculated f value <f table, then H0 is accepted. From the test results, the ANOVA Table 3 is obtained as follows:

| Table 3 Anova |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| 1 | Regression | 8,106 | 4 | 2,026 | 1,397 | ,237b |

| Residual | 2,82,914 | 195 | 1,451 | |||

| Total | 2,91,020 | 199 | ||||

The ANOVA Table above shows the value of F calculates as 1,397 with the level of F probability as 0,237. Because the value of F calculates 1,397<2,42 on significance level 0,237>0,05, H0 is accepted and Ha is rejected. Therefore, the independent variables simultaneously had no significant effect on the job satisfaction variable

The T-test is a separate or partial regression testing between each of the independent variables on the dependent variable. The testing was done to investigate whether each of the flexible work, specialized leave options, dependent care support, and religious support variables partially had a significant effect on the work-family conflict variable. The result of the t statistic test can be observed from Table 2 above provided that if the value of t probability were smaller than 0.05, Ha would be accepted and H0 would be rejected, while if the value of t probability were greater than 0.05, Ha would be rejected and H0 would accept (Ghozali, 2009).

Based on Table 2 for the value of each probability for the independent variables above, it can be observed that:

1) The probability t value for the flexible work variable was 0.101>0.05, while the value of t calculates was 1,648<t table namely 1,972. Therefore H0 was accepted, and Ha was rejected, so the flexible work variable had no significant effect on the job satisfaction variable

2) The probability t value for the specialized leave option variable was 0.712>0.05, while the value of t calculates was 0.369<t table namely 1,972. Therefore H0 was accepted, and Ha was rejected, so the specialized leave option variable had no significant effect on the job satisfaction variable.

3) The probability t value for the dependent care support variable is 0.323> 0.05, while the t value is 0.990 <t table, namely 1.972. Therefore H0 was accepted, and Ha was rejected, so the dependent care support variable had no significant effect on the job satisfaction variable

4) The probability t value for the religious support variable was 0.270>0.05, while the value of t calculates was 1,106<t table namely 1,972. Therefore H0 was accepted, and Ha was rejected, so the religious support variable had no significant effect on the job satisfaction variable.

The study's result shown in Table 4 indicates that two hypotheses are supported by research data, namely H2 and H4. It indicates that WLB policies: Specialized leave options, and religious support did prove to affect job satisfaction. The positive results of the two variables support several studies related to the implementation of WLB, which state that the implementation of WLB encourages positive employee attitude and behavior towards the organization, such as job satisfaction. According to social exchange theory, employees would feel obliged to exhibit favorable attitudes or behaviors towards their organizations when viewed favorably and benefit from them (Lambert, 2000; Wang et al., 2011).

| Table 4 Summary of The Findings For Hypotheses Testing |

||

|---|---|---|

| Hypotheses | b | Test Result |

| H1: Flexible work options have a Positive Impact on Job Satisfaction | -060 | Not Supported |

| H2: Specialized leave options have a positive impact on Job Satisfaction | ,024 | Supported |

| H3: Dependent care support have a positive impact on Job Satisfaction | -082 | Not Supported |

| H4: Religious support has a positive impact on Job Satisfaction | ,110 | Supported |

The philosophy of traditional gender roles and the patriarchal culture adopted in Indonesia requires women to assume greater domestic responsibility so that the specialized leave option policy can enable them to request reasonable time off for their family reason. It can help them balance their work-home life and generate positive feelings towards work, and likely experience job satisfaction (Blau, 1964; Birtch et al., 2015; Kalliath, 2020).

Religiosity issue is susceptible in Indonesia context, closely related to subjective well-being. It is regarded as a part of human identity in Indonesian culture (Colbran, 2010), so the religiosity support that the workplace provides can result in a more positive subjective feeling. This research succeeded in proving the positive role of WLB policies related to religiosity on job satisfaction. These findings are consistent with previous studies; improving employee welfare by growing positive feelings and reducing negative feelings may increase job satisfaction (Kaplan et al., 2009).

The study's result supported Afrianty (2013); Afrianty, Burgess & Issa (2016) by finding the negative effect of flexible work options and dependent care support on job satisfaction. The negative effect of the flexible work option is also stated by Byron (2015); Michell, et al., (2011). Although it provides work convenience by offering reduced formal hours, the Flexible work option cannot reduce the workload. The employee still has to catch up on their work responsibilities even by complete them at home. Instead of providing convenience, flexible working options can disrupt family moments because it is synonymous with "always open" or 24/7 work hours (Perrigino et al., 2018). Another possible reason is that autonomy agreements may minimize working hours but can lead to financial losses. These conditions have the potential to cause work stress, which can cause job dissatisfaction.

Dependent care support does not affect job satisfaction. Ineffectiveness of WLB policies implementation can be caused by employee perceptions of the relevance and appropriateness of WLB policies. In Indonesia, as countries with a collectivist culture, households are commonly inhabited by parents or other extended families. They sometimes assist these married employees in reducing the household burden and taking care of their children. Therefore, due to this possibility, the dependent care support policies examined in this research are not deemed appropriate for employees; therefore, they cannot increase their job satisfaction. As stated by self-interest theory and social exchange theory, individual’s behaviors are influenced by personal gain and benefit.

Some studies indicate that WLB policies are related to performance evaluation and career development (Casper et al., 2007; Hoober et al., 2009; Paustian-Underhal et al., 2016; Perrigino et al., 2018). Employees who often leave for family reasons are linked with career obstruction and fewer salary increases. By implementing WLB policies, employees' status would be noticeable and protrude in the workplace, and they may experience stigmatizing or excluding (Kirby and Krone, 2002). They fear it is said to be taking advantage of the WLB policy, to ignore their job duties. Particularly for women whose workplace skills, efficiency, and dedication were doubted (Brescoll et al., 2013). Stigmatization can come from the company and its fellow workers (social jealousy) (Perrigino et al., 2018).

Employees using WLB policies stated that to contradict the definition of ideal employees, where the ideal concept for specific organizations is to prioritize work over all facets of life. Even in advanced countries like Switzerland, the "maybe baby" phenomenon indicates that the organization and colleagues perceive women without children as uncertain with the ability to frustrate the organization when they decide to start having children (Perrigino et al., 2018).

Fear of colleagues' jealousy is another consequence that employees may be faced by taking advantage of WLB policies, primarily when not supported by the organization environment. A rise in workload triggered by the absence of workers benefiting from WLB policies becomes one explanation for jealousy. Moreover, they have also exposed a sense of discrimination against other groups who cannot enjoy WLB policies. One form of jealousy was the Childfree Network's existence as an advocacy group to defend the interests of non-child workers and state that WLB policies were discriminatory and likely spread a form of systemic discrimination in society (Rothausen et al., 1998; Perrigino et al., 2018).

Conclusion and Further Research

The research is a few research related to WLB policy' implementation in Indonesia. Based on the testing result, it is concluded that dependent care and religious support positively affect job satisfaction. However, the other two policies, flexible work and specialized leave option, did not affect job satisfaction. This study shows that WLB policies in Makassar were not effective in increasing job satisfaction among women workers. Therefore, instead of adopting the one size fits all" policy, organizations need to observe the policy's suitability and customize based on employees' actual need relevant to work-life balance policies.

The study only focused on WLB policies as antecedents of job satisfaction. Therefore, further studies need to be carried out using other factors capable of significantly affecting job satisfaction, such as superiors and co-workers’ influence or extended family and paid home care. This study uses a survey method for generalization purposes and time constraints. Future studies need to consider using other research methods such as the qualitative approach to understanding better respondents' insights and experiences in using WLB policies. Respondents of this study came from one city, Makassar; therefore, further research is expected to expand the scope of research for generalization purposes

References

- Anthony, A. (2017). "Exploring the role of work-family conflict on job and life satisfaction for salaried and self-employed males and females: A social role approach." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. Accessed 10/01/18 from http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/bus_admin_diss/86

- Afrianty, T.W. (2013). Work-life balance policies in the Indonesian context. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Curtin University, Perth

- Afrianty, T.W., Burges, J., & Issa T. (2015). Family-friendly support programs and work-family conflict among Indonesian higher education employees, Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion. An International Journal, 34(8), 726 - 741

- Afriany, T., Issa, T., & Burgess, J. (2016). Indonesian work-life balance policies and their impact on employees in the higher education sector. In Sushil, J. and Connell, J. and Burgess, J. (ed), Flexible Work Organizations, 119-133. India: Springer

- Ahmed, A. (2008). Job, family and individual factors as predictors of work-family conflict. The Journal of Human Resource and Adult Learning, 4

- Allen, T.D., Johnson, R.C., Kiburz, K.M., & Shockley, K.M. (2012). Work-family conflict and flexible work arrangements: Deconstructing Flexibility. Personnel Psychology, 66(2), 345–376.

- Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., De Boer, E., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2003). Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 341-356

- Bardoel, E.A. (2003). The provision of formal and informal work-family practices: The relative importance of institutional and resource-dependent explanations versus managerial explanations. Women in Management Review, 18(1/2), 7- 19.

- Birtch, T.A., Chiang, F.F.T., & Van Esch, E. (2015): A social exchange theory framework for understanding the job characteristics–job outcomes relationship: The mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management.

- Brough, P., Timms, C., O'Driscoll, M.P., Kalliath, T., Siu, O.L., Sit, C., & Lo, D. (2014). Work-life balance: A longitudinal evaluation of a new measure across Australia and New Zealand workers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(19), 2724-2744.

- Brown, S.P., & Peterson, R.A. (1993). Antecedents and consequences of salesperson job satisfaction: Meta-analysis and assessment of causal effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 30(1), 63–77

- Burgess, J., & Strachan, G. (2005). Integrating work and family responsibilities: Policies for lifting women's labor activity rates. Just Policy, 5-12.

- Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169-198.

- Brescoll, V.L., Glass, J., & Sedlovskaya, A. (2013). Ask and Ye shall receive?: The dynamics of employer-provided flexible work options and the need for public policy. Journal of Social Issues, 69(2), 367–388.

- Antonia, C.S., Salinas, J.M., Lecea, M., & González, A.M.C. (2011). Work–family and family–work conflict: Does Intrinsic–extrinsic satisfaction mediate the prediction of general job satisfaction? The Journal of Psychology, 145(5), 435-461

- Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, G.D., & Klesh, J.R. (1975). Michigan organizational assessment Package, accessed from http://docshare01.docshare.tips/files/23906/239068612.pdf

- Devi, K.R., & Rani, S.S. (2016). The impact of organizational role stress and work-family conflict: Diagnosis sources of difficulty at work place and job satisfaction among women in IT sector, Chennai, Tamil Nadu. Procedia- Social and Behavioral Sciences, 219, 214-220.

- Drago, R., & Kashian, R. (2003). Mapping the terrain of work/family journals. Journal of Family Issues, 24(4), 488-512.

- Frone, M.R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M.L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65-78.

- Frone, M.R. (2000). Work-family conflict and employee psychiatric disorders: The National Comorbidity survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(6), 888-95.

- Imam, G. (2009). Multivariate analysis application with SPSS program, (4th Edition). Semarang: Diponegoro University Publishing Agency.

- Greenhaus, J.H., Collins, K.M., & Shaw, J.D. (2003). The relation between work-family balance and quality of life. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 510–531.

- Greenhaus, J., & Powell, G. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31, 72-92.

- Greenhaus, J., & Allen, T. (2011). Work-family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In J. C. Quick and L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (2nd edition). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Gurbuz, S., Turunc, O., & Celik, M. (2012), "The impact of perceived organizational support on work-family conflict: Does role overload have a mediating role? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 6(3)

- Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139

- Harter, J.K., Schmidt, F.L., & Hayes, T.L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268-279.

- Haar, J.M. (2013). Testing a new measure of WLB: A study of parent and non-parent employees from New Zealand. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(17/18), 3305–3324.

- Kahn, R.L., Wolfe, D.M., Quinn, R.P., Snoek, J.D., & Rosenthal, R.A. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. John Wiley.

- Kalliath, T., & Brough, P. (2008). Work-life balance: A review of the meaning of the balance construct. Journal of Management and Organization, 14(3), 323-327.

- Kalliath, P., Kalliath, T., Chan, X.W., & Chan, C. (2020). Enhancing job satisfaction through work-family enrichment and perceived supervisor support: The case of Australian social workers. Personnel Review

- Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2010). Doing more with less?: Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63(1), 83-106

- Kirby, E., & Krone, K. (2002). The policy exists, but you can't really use it: Communication and the structuration of work-family policies. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 30(1), 50–77

- Kossek, E.E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 139-149.

- Kossek, E.E., Valcour, M., & Lirio, P. (2014). The sustainable workforce: Organizational strategies for promoting work-life balance and well-being. In C. Cooper & P. Chen (Eds.), Work and Well-being, 295–318, Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lambert, S.J. (2000). Added benefits: The between work-life benefits and organizational citizenship behaviour. Academy of Management Journals, 43(5), 801–815.

- Lee, S.Y., & Hong, J.H. (2011). Does family-friendly policy matter? Testing its impact on turnover and performance. Public Administration Review, 870-879

- Edwin, A. (1976). In Dunnette, Marvin D. (Ed.). The nature and causes of job satisfaction, 1297–1349. Chicago: Rand McNally College Publishing Company.

- Lu, H., While, A.E., & Barriball, K.L. (2007). Job satisfaction and its related factors: A questionnaire survey of hospital nurses in Mainland China. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(4), 574–588

- McCarthy, A., Darcy, C., & Grady, G. (2010). Work-life balance policy and practice: Understanding line managers attitudes and behaviors. Human Resource Management Review, 20, 158-167.

- Mittal, S. (2017). How employers in Indonesia can harness the full potential of female employees. The Jakarta Post. Retrieved from https://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2017/01/16/how-employers-in-indonesia-can-harness-the-full-potential-of-female-employees.html

- Orpen, C. (1981). Effect of flexible working hours on employee satisfaction and performance: A field experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66(1), 113–115

- Perrigino, B., Benjamin, B., & Wilson, K.S. (2018). The Academy of Management Annals, 12(2), 600-630.

- Post, T.J. (2012). Indonesia concerned about work-life balance. The Jakarta Post. Retrieved From https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/11/01/survey-shows-indonesians-worry-about-work-life-balance.html

- Rothbard, N.P. (2001). Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 655–684.

- Ryan, A.M., Schmitt, M.J., & Johnson, R. (1996). Attitudes and effectiveness: Examining relations at an organizational level. Personnel Psychology, 49, 853–882

- Sat. (2012). Indonesians concerned about work-life balance: Survey, The Jakarta Post. accessed from http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/10/31/indonesians-concerned- about-work-life-balance-survey.html

- Schneider, B., Hanges, P.J., Smith, D.B., & Salvaggio, A.N. (2003). Which comes first: Employee attitudes or organizational financial and market performance? Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 836–851.

- Ahmed, S.A., Breitenecker, R.J., & Shah, S.A.M. (2017). Relation of work-life balance, work-family conflict, and family-work conflict with the employee performance-moderating role of job satisfaction. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 7(1), 129-146.

- Sundaresan, S. (2014). Work-life balance – implications for working women. OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(7), 93-102.

- The World Bank. (2013). IFC championing women on corporate boards in Indonesia. Diakses 10/01, 2018, from http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013/07/31/ifc-championing- women-on-corporate-boards-in-Indonesia

- Wang, P., Lawler, J.J., & Shi, K. (2011). Implementing family-friendly employment practices in the banking industry: Evidence from some African and Asian countries. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84, 493- 517.