Review Article: 2026 Vol: 30 Issue: 1

A Consumer and Business Centric Approach To Expand Businesses Selling Organic Products Geographically Using Franchise Business Model and Real-Time Sentiment Analysis

Prakash M C, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur, Chennai

Dinesh J, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur, Chennai

Citation Information: Prakash, M.C., & Dinesh, J. (2026) A consumer and business centric approach to expand businesses selling organic products geographically using franchise business model and real-time sentiment analysis. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 30(1), 1-5.

Abstract

The demand for organic products is on the rise in developed and developing countries. Primarily, this demand is fueled in developed and developing countries by increasing awareness among consumers about the health benefits of consuming organic products and the readiness to spend more money on such products. The advantages of this increased demand to our surrounding environment are reduced pollution, increased biodiversity, enhanced soil health etc., due to promotion of eco-friendly farming practices. The supply required to meet this demand is provided by organic stores, aggregators etc. through various offline and online modes such as retail outlets in locations where there is a demand for organic products, mobile applications, websites, social media applications etc. The required organic products are bought from farmers who cultivate such organics products locally by organic stores, aggregators etc. The key aspect that consumers are concerned about is the freshness of organic products that they consume for which procuring such organic products locally is crucial. However, procuring such organic products locally becomes a challenge when businesses try to expand their presence geographically. This research article focuses on addressing this challenge using franchise business model and real-time sentiment analysis. The proposed model “Consumer and business centric freshness-expansion model” not only addresses this challenge but also makes it applicable to all developed and developing countries by making necessary customizations, if necessary.

Keywords

Organic Products, Freshness, Geographical Expansion, Consumer Centric, Business Centric.

Introduction

In recent years, organic products are gaining more popularity among consumers in developed and developing countries. Global warming, unhealthy lifestyle, COVID-19 pandemic, rise in percentage of people getting affected by chronic diseases, increase in mortality rate of middle-aged people etc. have shifted the focus of consumers in developed and developing countries from medicine to food. When it comes to food, organic products (organic food products) are the most sought-after alternative among consumers. The advantages of consuming organic products to our surrounding environment are reduced pollution, increased biodiversity, enhanced soil health etc., due to promotion of eco-friendly farming practices (Brata et al., 2022).

Since both awareness about importance of health and affordability are required to purchase and consume organic products, consumers in developed and developing countries are increasing in terms of converting from inorganic products (inorganic food products) to organic products. Freshness is a critical aspect of organic products and hence organic products are cultivated by organic farmers locally. These organic products are either sold directly to the consumers or sold to retailers like organic stores, aggregators etc. who in-turn sell them to consumers through offline and online modes.

Literature Review

Demand for Organic Products in Developed Countries

The organic food and beverage market is projected to exceed $500 billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of over 10%. Developed regions such as North America, Europe, and Australia are leading in organic consumption due to stringent food safety regulations and consumer preference for chemical-free products. The rise of plant-based diets and functional foods has further accelerated organic farming expansion.

Consumers are increasingly avoiding synthetic pesticides, herbicides, and GMOs, preferring organic foods for their perceived nutritional benefits. Organic farming supports regenerative agriculture, improving soil health, carbon sequestration, and biodiversity. Many governments are attracted by the health benefits of organic foods and hence are interested in promoting organic farming, by offering subsidies and certifications for organic farming (Lockie et al., 2006; Sahota, 2010).

Organic products segment is the largest and most profitable segment, benefiting small farmers and direct-to-consumer models like farmers’ markets. High demand is there for organic wheat, rice, quinoa, and sorghum, especially in gluten-free and plant-based food industries. Consumers prefer grass-fed, antibiotic-free, and hormone-free dairy and meat products.

Organic products often cost more due to labor-intensive farming and certification costs. Limited availability and distribution challenges can affect market growth. Inflation and rising food prices have impacted consumer purchasing power in some regions.

The European Union aims to achieve 25% organic farmland by 2030, requiring sustained efforts. Organic imports into the EU and USA have shown an upward trend, indicating strong demand. Technological advancements in organic farming, such as AI-driven precision agriculture, are expected to improve efficiency and yield.

Demand for Organic Products in Developing Countries

Organic farming is expanding in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, driven by consumer demand, export opportunities, and government support. Local organic markets are emerging, with farmers selling directly to consumers through farmers’ markets and cooperatives.

There is a high demand for locally grown, pesticide-free produce. Growing interest for organic rice, wheat, quinoa, and millet cultivation in developing countries is due to the increasing demand for these organic products in developed countries.

Many consumers in developing countries are less familiar with organic products’ benefits, which may affect its demand (Suharjo et al., 2013). There is a lack of infrastructure and distribution networks in developing countries which in turn can hinder market growth of organic products.

Agro-tourism models and local participatory certification systems are emerging to support organic farming. Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) are network-based certification models that foster trust and mutual learning among producers and consumers of organic products. While developed countries are the primary consumers, developing countries are becoming important producers and exporters of organic products (Pantovi? & Dimitrijevi?, 2018). Organic products’ exports from developing countries to Europe and North America are increasing.

Challenges Faced by Businesses Selling Organic Products

Organic products have a shorter shelf life, requiring efficient cold storage and transportation. Many regions lack proper storage, distribution networks, and transportation facilities. Organic products often require special handling, thereby increasing logistics expenses.

Different countries have varying organic certification requirements, making compliance complex. Some countries impose strict import regulations on organic products. Businesses must adapt packaging and labeling to meet local regulations.

Organic products are more expensive, limiting affordability in certain markets. In some regions, organic food benefits are not well understood, thereby affecting its demand. Local food habits may not align with organic product offerings, requiring adaptation.

Competing with established local organic farms can be difficult. Securing shelf space in supermarkets and grocery stores requires strong branding. Online sales of organic products demand robust digital marketing and efficient delivery systems.

Expanding requires significant capital for infrastructure, marketing, and distribution. Uncertain demand and economic fluctuations can impact profitability. Accessing government grants or private investment is crucial for scaling operations.

Scaling up while ensuring organic integrity is challenging. Expansion may lead to higher carbon footprints, requiring sustainable solutions. Businesses must ensure fair wages and ethical farming practices.

Discussion

Research Gap

Though businesses selling organic products to organic products consumers are able to maintain the freshness (one of the key value-additions of organic products) of organic products sold when such products are sourced locally and sold locally, they find it challenging when they are trying to expand geographically (Kamarapu et al., 2025; Münchhausen & Knickel, 2014).

Research Objective

To overcome the geographical expansion challenge faced by businesses selling organic products to organic products consumers without compromising on sourcing locally for freshness of organic products. Franchise business model and Sentiment Analysis can be used to overcome this challenge.

Proposed Model

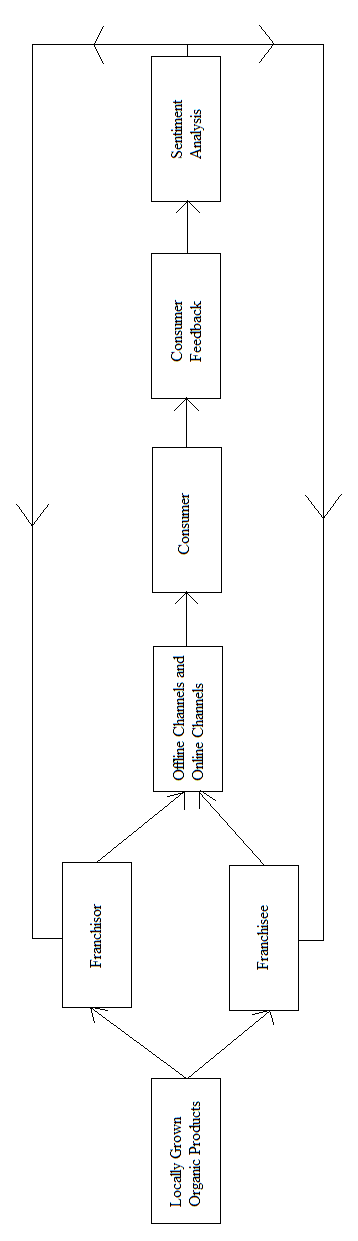

The proposed model “Consumer and business centric freshness-expansion model” is shown below in Figure 1. Initially, locally grown organic products are sourced from farmers by the Franchisor and Franchisees followed by selling the locally sourced organic products to consumers through offline and online modes such as retail outlets, mobile applications,websites, social media applications etc. Consumers are requested to give feedback and sentiment analysis is done in real-time on this feedback. The results of sentiment analysis are shared in real-time to the franchisor and franchisees to ensure sustainability of this business model.

A franchise business model is a system where a business (the franchisor) grants individuals or companies (the franchisees) the right to operate under its brand, using its established business processes and trademarks (Ruster et al., 2003). In exchange, franchisees typically pay an initial fee, a share of their revenue in an ongoing manner and royalty (Mathewson & Winter, 1985).

Sentiment analysis, also known as opinion mining, is a Natural Language Processing (NLP) technique that uses machine learning and text analysis to determine the emotional tone behind a piece of text (Tejwani, 2014). It helps businesses, researchers, and organizations understand public opinion, customer feedback, and social media trends.

Conclusion

This research article discusses about the demand for organic products in developed and developing countries, stresses on the importance of sourcing organic products locally in order to ensure their freshness which is one of the key value-additions of organic products, the challenge faced by businesses (franchisors) in expanding geographically without compromising on freshness and proposes a model to overcome this challenge using Franchise business model and Sentiment Analysis.

References

Brata, A. M., Chereji, A. I., Brata, V. D., Morna, A. A., Tirpe, O. P., Popa, A., & Muresan, I. C. (2022). Consumers’ perception towards organic products before and after the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study in Bihor County, Romania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12712.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Golijan Pantovi?, J., & Dimitrijevi?, B. (2018). Global organic food market. Acta Agriculturae Serbica, 23(46), 125–140.

Kamarapu, S., Agnihotri, R., & Roopashri, V. (2025). Delivering freshness: Country Delight’s customer-centric approach to subscription-based delivery. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(S5), 1–3.

Lockie, S., Halpin, D., & Pearson, D. (2006). Understanding the market for organic food. In Organic agriculture: A global perspective (pp. 245–258). Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing.

Mathewson, G. F., & Winter, R. A. (1985). The economics of franchise contracts. The Journal of Law and Economics, 28(3), 503–526.

Münchhausen, S., & Knickel, K. (2014). Growth, business logic and trust in organic food chains: An analytical framework and some illustrative examples from Germany.

Ruster, J., Yamamoto, C., & Rogo, K. (2003). Franchising in health: Emerging models, experiences, and challenges in primary care.

Sahota, A. (2010). The global market for organic food and drink.

Suharjo, B., Ahmady, M., & Ahmady, M. R. (2013). Indonesian consumers’ attitudes towards organic products.

Tejwani, R. (2014). Sentiment analysis: A survey.

Received: 18-Jun-2025, Manuscript No. amsj-25-16009; Editor assigned: 20-Jun-2025, PreQC No. amsj-25-16009(PQ); Reviewed: 04-Jul-2025, QC No. amsj-25-16009; Revised: 20-Feb-2026, Manuscript No. amsj-25-16009(R); Published: 27-Feb-2026