Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 3

Analysis of Digital Marketing Strategies for Artists During the Pandemic

Medardo Amyr Sarmiento Carmona, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Ecuador

Angel Torres-Toukoumidis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Ecuador

Abstract

Digital spaces have the potential to enhance the engagement of spectators, and the evolving digital interaction is making a tremendous change in art marketing. But this digital sphere requires comprehension of the new codes that have emerged, to lead to innovative synergies between the online and the offline world. Which only can be enhanced with bi-directional interaction, setting to interlock, involve and cause the spectator’s attention. The arrival of Covid-19 to Ecuador has been a big opportunity to advance in ICT dissemination and digital mediation techniques, even though it’s not enough to replace collective experience. This research is oriented to analyze the digital marketing strategies for artists and artistic products during the Covid-19 pandemic. It’s an inductive quanti-qualitative approach, with a micro-ethnographic design, and we applied semi-structured interviews. We interviewed seventeen artists, producers, cultural managers, and cultural promotors from several fields of cultural activity in Cuenca, Ecuador. We looked for persons implicated in art projects during the sanitary emergency in the country. We’ve analyzed about nineteen projects in total, with a twenty questions questionary. The procedure of this research is to collect, systematize, and analyze all data we’re using with MAXQDA software. This study showed us that the arts and cultural sector are complex. Artists use to manage and promote events too, in other cases must generate formative processes like a sustainable source of income. This scenario turned out more complex, although, a part of the projects held on the pandemic and have created new kinds of entertaining and interactive content. Also, there is a thin line between entertaining and building community content. Finally, we found out that giving priority to customer loyalty is an indicator of high levels of cultural marketing practices.

Keywords

Interaction, Marketing Strategy, Artists, Customer Loyalty. ICT.

Introduction

When we talk about marketing, we refer to brands and consume. Despite brands and art operate on the same symbolic dimension, traditional marketing and arts marketing do not relate to the same knowledge spectrum. While traditional marketing starts on a need to fill and then make a specific product for it, arts marketing starts directly on the product and then looks for the best audiences to reach. The sequence of the marketing mix is different, so the creative process is a fundamental gear to promote art and engage audiences (Cuenca, 2015; Kubacki & O’Reilly, 2009).

Until 1984, arts marketing had the focus on the education of audiences and the economy of the arts. Ten years after that, the researchers were focused on applying the marketing notions to non-profit arts organizations.

Just in 1995 took place the consumer behavior and social sciences to reach new audiences (Kubacki & O’Reilly, 2009). So, based on its history, arts marketing is not about forcing the making of some specific product but fitting the product in the precise audience. Anyway, the artist always must execute a sensibilization phase to get into the public and its perceptions (Cuenca, 2015).

Plattner (High art down-home: an economic ethnography of a local art market, 1996) already expresses those artists sell their work as a commodity, although the production of it involves an intensely creative and personal process. That process could be found in any artistic expression, in its way, and could be the key to engage audiences. On the other hand, according to Cuenca (2015), right now just big stars’ image is effective to convince audiences, in other cases artists’ image is not the best tactic to sell any artwork. That is why the creative process should take an important role in art and cultural promotion. Nevertheless, if we want to reach new audiences, the best way is to produce something known for them. In other words, you cannot expect your public growth if your product is too extravagant. Even in the promotion process, we should tell stories that easily captivate our specific target, meaning that artists and cultural managers must link their interpretations with perceptions and expectations of the audience, building strong bonds not only between the target and the artist but with the artwork too. Both audiences -existing and new onesmust be targets of this work, but former spectators/customers could have deeper needs about it (Le et al., 2015; Walsmley, 2016).

Bonds have a series of benefits, the main one is customer loyalty. As a consequence, clients will be more tempted to consume future products and, more importantly, will share positive references about the product, promoting and extending to potential audiences (Cuenca, 2015). However, in order to achieve new customers loyalty, playing something interesting for them is not as important as generating satisfactory experiences. The frequency of assistant will show how satisfactory were those experiences (Gomez et al., 2019).

Cultural managers have an important role in arts marketing, basically, cultural managers deal with the fluctuation of economy, politics, competitive activities and customer behavior, also exist symbolic issues that get into the equation, especially in the no-mainstream art sector. Art and culture operate in an intellectual and symbolic sphere, the audience requires translation. In other words, promotion not only must introduce the artwork but overall translate it (Kubacki & O’Reilly, 2009). There are different audiences and each one has distinctive symbols. These niches manifest themselves in diverse ways and layers of interactions with their world. Cultural managers’ work consists in engage the symbolic content of the artwork with the understood symbols and shared conventions of its proper audience. That’s why should know perfectly the product and the target, and find the cultural connections between both (Buchholz et al., 2020).

Kubacki & O’Reilly (2009) manifest that the big challenge of an art marketer is “to be a situationist” (p.65). Any arts marketing strategy must be adapted to the multiple factors that affect each product managed. This work not only relies on segmenting the audience and targeting ads, even less in the digital age. Nowadays, the evolving digital interactions are making a tremendous change in the culture markets and art marketing, are expanding the potential reach to the whole world and with no time limits (Lee & Lee, 2018).

Arts Marketing’s Interactions in The Digital Age

The arrival of ICT circulation of art products is opening new market opportunities, regarding this situation, the cultural ecosystem is getting diverse, competitive and specialized ICT has become and should be a bridge between physical and digital dimensions. Digital spaces have the potential to enhance the engagement of spectators, without bodily limitations. Furthermore, cultural management depends every day less on public bureaucracy, so it’s getting a direct interaction (Barenboim, 2014; Buchholz, 2020).

With the introduction of ICT, the new challenge is comprehending related phenoms to human sensibility through interaction. Thus, social media could be very efficient in generating it, even though it involves new kinds of codes. The digital world is a perfect platform for innovative synergies, and it’s turning arts and culture into daily consumable goods. Only bi-directional interaction can enhance the art experience. Such online art marketing allows participative cocreation, which means more empowered and sensitized audiences. After all, ICT is a new communication channel creating a new set of language, with new symbols and new perceptions. The boundaries of art have dilated, digital technologies have influenced its creation, curation, and promotion. The expectation of audiences is not the same either. As a tactical solution, Xin Kang and collaborators (2019) realized that active “digital interaction with the audience can promote cognitive decoding and enhance kinesthetic and emotional responses to artistic activities” (p.3). Art marketers must interlock, involve and cause that attention, through interaction. In the words of Steven Tepper (2008), that precisely is to achieve engagement, because younger audiences want to connect with art products they consume. They have new kinds of needs like discovering new symbols and meanings and producing their content as resumes and critiques, based on their interpretations. All this know-how of art marketing and digital interaction has been the starting point to deal with the Covid-19 pandemic in the cultural sector (Aburto, 2009; Barenboim, 2014; Walsmley, 2016).

Arts Marketing from COVID-19 Crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a severe economic and social impact, every market was dramatically affected, but the arts and culture sectors have suffered the biggest kick. Although, perhaps the viral emergency just made more visible the problems this sector already had much before the pandemic (Betzler et al., 2020). Cultural jobs have collapsed, and venues had to close doors for a very long time, so many of them were bankrupt. This situation has increased the precarity of the arts sector. But, between the many issues of this industry, there is the public value about it: people do not take artistic activities as essential goods, not before and now even less. So, nowadays arts marketers have enormous new challenges not only to reach new audiences but to get former audiences back too (Banks & O’Connor, 2020).

An important part of an artistic experience is socializing and cultivating personal and leisure networks. Face-to-face presence is more likely to engage an audience with ‘that artist on stage’ (Buchholz, 2020). This actively demonstrates that the COVID-19 pandemic has been a big opportunity to advance in ICT and digital mediation techniques, even though it’s not enough to replace collective experience (Betzler et al., 2020).

Although digital actions will never replace face-to-face experience, the real social media potential is to build a community, cultivating connections with increased accessibility facilitating involvement, loyalty, co-creation and co-financing. Furthermore, no longer former targets could be actors and beneficiaries, also people that could have geographical, financial, or healthy restrictions to consume the product (Ryder, 2020).

The following research is presented from an innovative approach due to the fact that there are few studies about arts marketing in the Latin American context. Most of them are from the USA and Europe. The pandemic crisis seems to be changing the forms of interaction related to art. Therefore, it is prescribed to know the incorporation of digital marketing strategies in the promotion of the cultural sector in Ecuador considering the experiences of artists.

Methodology

This research is oriented to analyze the digital marketing strategies for artists and artistic products during the COVID-19 pandemic (gen. obj.). While the specific objectives are: [1] to explore the level of use of social media and digital marketing tools to promote artists and artistic products during the COVID-19 pandemic, [2] to determine the interaction and engagement levels resulted from the initiatives of digital art marketing, and [3] to set up an action plan in order to enhance the digital promoting of artists and artistic products.

The methodology of this paper is based on Cuenca’s research (2015). This is an inductive quanti-qualitative approach, with a micro-ethnographic design, and we apply semi-structured interviews.

We’re going to analyze how the arts sector from Cuenca, Ecuador, is managing its digital marketing strategies in the COVID-19 crisis. So, the starting point from some particular cases is to extrapolate general conclusions about effective and non-effective digital marketing strategies for artists and artistic products in the Latin American context (inductive approach). To do this, we need to collect and systematize some data (quantitative approach) about engagement and interaction of social media. And it’s also important to explore the ideas and experiences of arts marketers (qualitative approach).

The micro-ethnographic design refers to explore experiences and significations from specific niches in their own environment (qualitative), in this case, will be professionals of the arts sector. Also, we’re collecting data (quantitative), so this is a mixed investigation.

Data Collection Technique

Firstly, we’re making semi-structured interviews with seventeen artists, producers, cultural managers, and cultural promotors of several fields of cultural activity from Cuenca, Ecuador: scenic arts, cinema, music, visual arts, formative processes, institutional processes, and events production. They were selected by the convenience of this research and based on the experience of the researcher. We looked for persons implicated in art projects during the sanitary emergency in the country. We’ve talked and analyzed about nineteen projects in total. Also, we’re making a non-participant observation, which means the information has been collected with no interference from the researcher.

While structured interviews are too rigid for deep researching, with semi-structured interviews exists some margin of flexibility to explore detailed information about any experience or knowledge (Whiting, 2008).

We’ve made a questionary with twenty questions, which are categorical questions, rating scale questions, and open-ended questions. The questionary was the same for every interviewee, with little form changes according to each case.

The procedure of this research is to collect, systematize, and analyze all data we’re using with MAXQDA software. This is a software for mixed-method researches and allows to analyze of all kinds of data. The information has been coded only qualitatively. It was coded based on similar possible answers to each question. We got 529 coded text segments from the transcription of the interviews.

Data Analysis

From seventeen cultural actors’ interviews and about nineteen different projects. We asked what their project about is and interviewees mentioned and frequency of communication is applied for. Table 1 shows the combination of these labels in each of 17 interviews.

| Table 1 Fields of Activity Configuration Of Codes | |

| Frequency | |

| Visual arts | 2 |

| Scenic arts | 2 |

| Formative + Music | 1 |

| Collective + Event | 1 |

| Music | 1 |

| Formative + Cinema | 1 |

| Artistic communication + Event | 1 |

| Formative + Scenic arts + Event | 1 |

| Artistic communication + Institutional processes | 1 |

| Scenic arts + Collective | 1 |

| Cultural venue | 1 |

| Event | 1 |

| Cinema + Artistic Communication | 1 |

| Music + Visual arts | 1 |

| Artistic communication | 1 |

Of all 19 projects, four of them were one-person projects. So, the directors also were in charge of the dissemination of their projects. Three interviewees were communication professionals, two do the PR, and two have experience in marketing. The other eight projects have diverse conditions about the people involved in them.

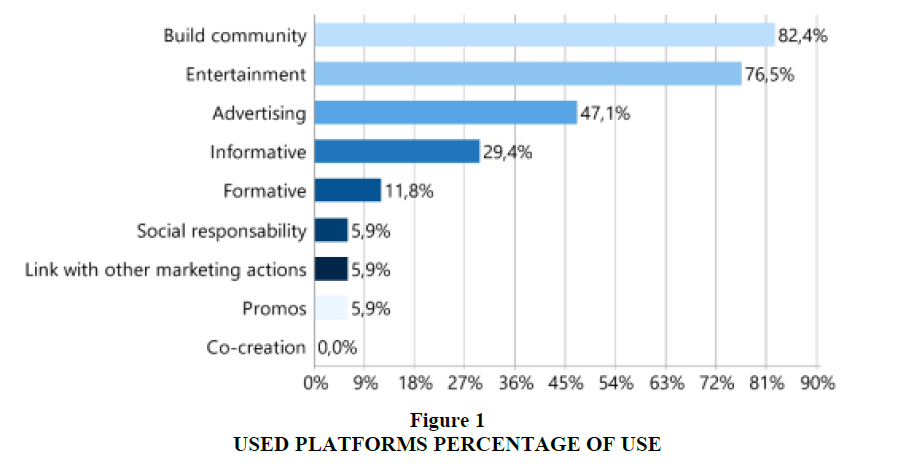

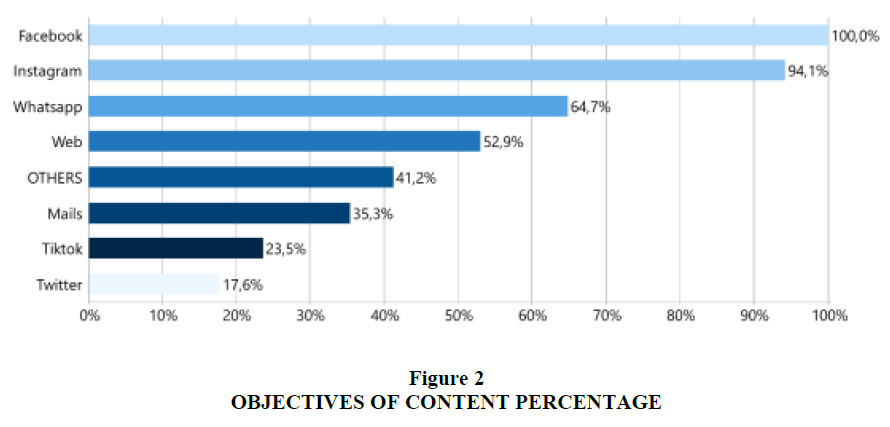

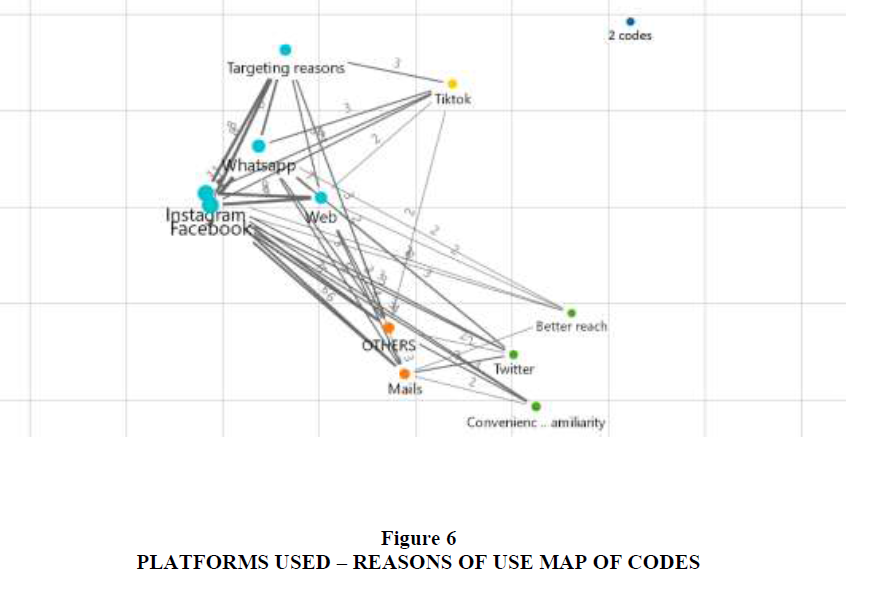

The most used platforms for promotion were Facebook by the 17 interviewees, and Instagram by 16. Following WhatsApp (11) and a website (9). In “others” category (7) there are cultural agendas like Cuyker, travel forums like TripAdvisor, and YouTube, which only in two cases is used with a marketing purpose. Mailing had 6. Every user of TikTok (4) is just beginning with this app. On the other side, Twitter (3) is not only the less used platform, but it is used very infrequently Figure 1.

Eight people choose the platforms based on targeting reason. That means the target of their projects was active in those specific platforms. These eight persons use Facebook and Instagram, and six use WhatsApp. Four bases the platform decision on their familiarity with it. And two of them are based on better numerical reach.

Interviewees were inquired about the kind of content in these platforms to determine the objectives of this content. We find out that fourteen people make it to build a community and thirteen to entertain. Eight people post advertising and five post informative content like interviews on radio or press Figure 2. Theory mentions the possibility of co-create artistic products, however, no interviewee has taken action with this objective.

Six interviewees do not recognize the engagement concept, but five have an advanced acknowledgement of this term. On the other side, about interaction term, six people have basic recognizing and another six’s it’s advanced. Otherwise, only four persons were sure of knowing advanced techniques of digital marketing.

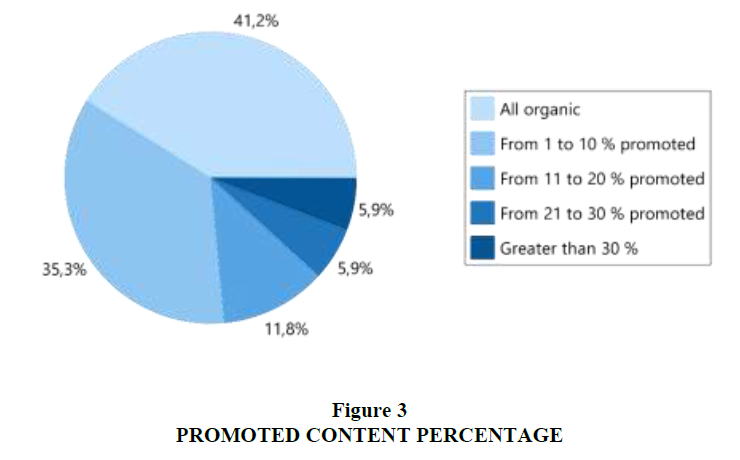

We asked how much of their content is promoted, seven interviewees rather stand with organic content only, and six promote it just a little, just the other four promote more than ten percent of their content Figure 3.

Five people promote the advertising content, and three rather promote better-interacted posts. 80 % of the people who rather organic content only manifested that paying used to be counterproductive. On the other hand, on promoted posts, four people apply advanced segmentation criterion, and three has intermediated criterion.

When it comes to measuring results, ten use the metrics of the platform itself, five use an intuitive measuring, and three measure by conversion. It must be said that some people use more than one metric tool. On other hand, nine interviewees don't use any social media managing app.

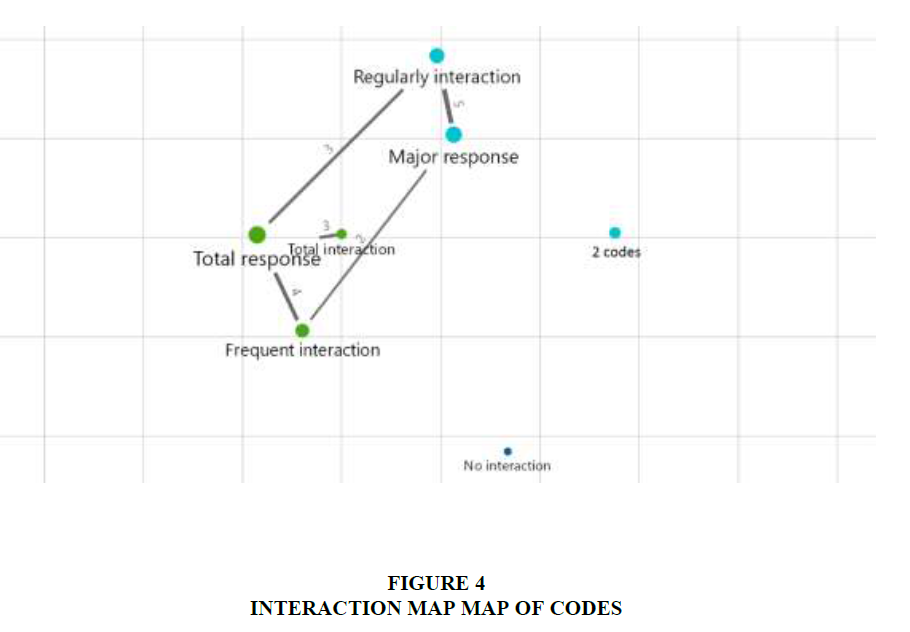

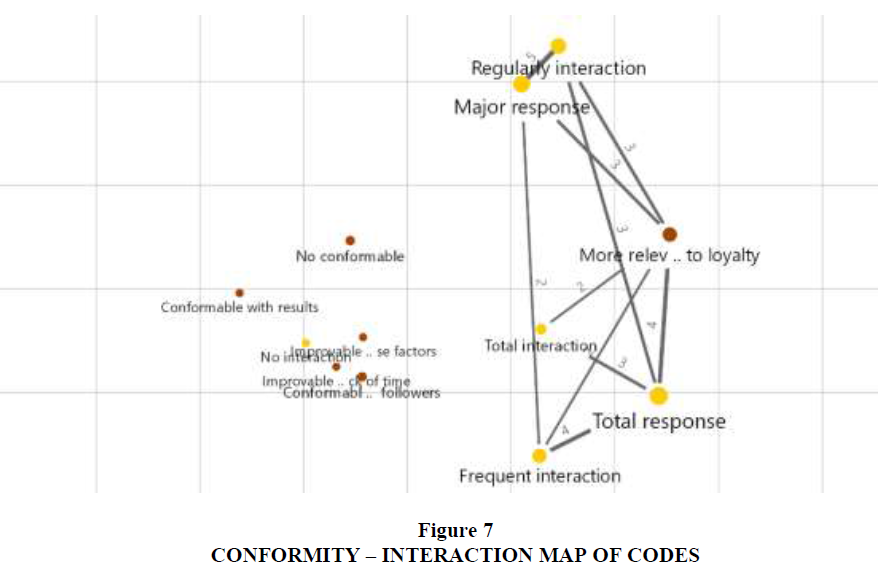

About interaction into their social media accounts, seven projects (41,2 %) have regular interaction and six (35,3 %) manifested frequent interaction. As well as interaction with the audience, nine projects (52,9 %) assure to respond to every comment and message, and eight (47,1 %) respond to the majority of comments and messages. There are five coincidences between regular interaction and a major response, and four coincidences between frequent interaction and total response Figure 4.

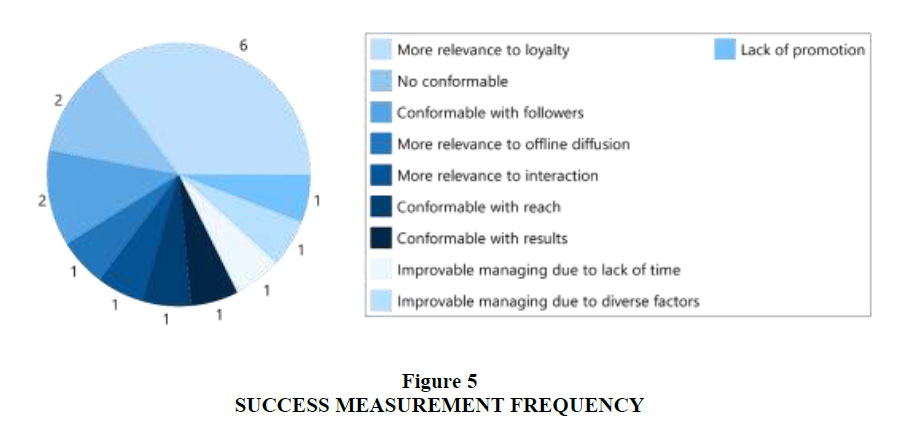

We asked about their conformity with the number of followers, with the intention of know how relevance they give to this variable. Actually, six interviewees give more relevance to customer loyalty. The other ones gave varied answers Figure 5. Finally, about their future vision, seven people (41,1 %) said that are thinking of hiring a professional for promotion, four (23,5 %) said they need to improve their strategy, and three (17,6 %) will increase engaging content, increase followers and get more promotion education.

Evidently, because of the high frequency of Facebook and Instagram use, and the prevalence of building community and entertainment objectives, the coincidences between these platforms and this kind of content are numerous. Both platforms and WhatsApp also have many co-occurrences with targeting reasons for their use Figure 6.

As well as, the co-occurrence between build community, entertainment, and the relevance given to customer loyalty is large. In addition, this last variable is related to a high level of interaction Figure 7. However, between the level of interaction and objectives of content, there is not any surprising association.

Each six interviewees that gives more relevance to loyalty manifested to be very conformable with the loyalty of their audiences, but, at the same time, they expect it to increase. Some of the specific actions of these people were stories with storytelling, valuable content, posting about the artists involved, diffusion with direct messages, expectative campaigns, reels and videos, taking pictures of popular people in events, a good hashtag strategy, and entertainment for quarantine.

Discussion and Conclusion

The first issue realized with this study is that the arts and cultural sector is complex. An artist is not only an artist, in some cases, artists manage and promote events too, in other artists must generate formative processes like a sustainable source of income. More than 20 % were one-person projects, which means the artist, or the cultural manager is his or her own marketing department. In the case of the cultural venue, we should understand that the most important stakeholder of it are the artists. It's almost the same with the public institution’s employee interviewed. Of course, from the pandemic, this scenario turned out more complex. A lot of artistic projects lost people of their teams, because of different reasons. That's why a little part of those got less activity on their social media accounts. Unlike, the other part, the people who held on during the pandemic created a new kind of content and focused more on entertainment (and interactive) content.

Art has an inevitable entertainment dimension, by its own nature. This condition made difficult the differentiation between this objective of content and building community. So, build community is more associated with valuable content and intending to get niche integration, while entertainment is content the audience can spend the time with. Even though, the line between these two kinds of content is thin. Posting a song is to create entertaining content, but labeling their Facebook friends in that posted song is a building community action. Also, the entertainment content could build a community too.

Meaning that the same song is capable of getting some niche integration. Similar thing is with the platforms’ stories, basically it’s entertainment content, but it has potential to build community too, especially if uses elements to interact with it. No one has tried digital co-creation, and it's worrying because that's one of the most recommended uses of the digital sphere, even more in pandemic times.

Despite people rather stand with organic content only, most of the professionals have some percentage of promoted content. Also, most of the people who pay promotion this much do it in better-interacted posts. Otherwise, there are projects too in which paid promotion is indeed counterproductive, but this kind of projects requires being really active on social media. People who prefer to stand organic content use to measure Key Performance Indicators with the metrics of the platforms. Although, every marketing or communication professional has not only one metric tool but mixed between technical apps and their own measurements. As well as, an advanced segmentation strategy is linked to better interaction and engagement, which only almost 20 % of the interviewees applied. This is a segmentation based not only on interests and demographics, but varied targets with differentiated messages to each one, and the necessary improvements depending on the interaction received. There is a direct relation between interaction from the audience and with the audience. This means that a high level of interaction with the audience could incentive the audience to interact back. High levels of interaction also are related to the relevance given to loyalty.

We found out that giving priority to customer loyalty is an indicator of high levels of cultural marketing practices because it's associated with better results according to interaction and engagement.

References

- Aburto Morales, S. (2009). Arte y comunicación. El objeto en el transobjeto. Razón y palabra, 66(1), 1-44.

- Adam, G. (2014). Big bucks: The explosion of the art market in the twenty-first century. London, United Kingdom: Lund Humphries.

- Adegbola, O., S. Gearhart, J. Skarda-Mitchell (2018). Using Instagram to engage with (potential) consumers: A study of Forbes most valuable brands’ use of Instagram. The journal of social media in society, 7(2), 232-251.

- Banks, M. & J. O’Connor (2020). “A plague upon your howling”: art and culture in the viral emergency. Cultural trends, 20(1), 1-17.

- Barenboim, L. (2014). Gestión cultural 3.0. Centro de estudios en diseño y comunicación, 50(1), 91-101.

- Betzler, D., E. Loots, M. Prokupek, L. Marques & P. Grafenauer (2020). COVID-19 and the arts and cultural sectors: Investigating countries’ contextual factors and early policy measures. International journal of cultural policy, 20(1), 1-20.

- Buchholz, L., G.A. Fine & H. Wohl (2020). Art markets in crisis: how personal bonds and market subcultures mediate the effects of COVID-19. American Journal of Cultural Sociology, 8(1), 462-476.

- Calderón Garzón, S.P., S.P. Caviedes Caviedes & Y.K. Parra Acosta (2019). Las variables sociodemográficas y su incidencia en la asistencia a eventos culturales: Caso Colombia. Espacios, 40(16), 13-21.

- Chan, T.W. & H. Turner (2017). Where do cultural omnivores come from? The implications of educational mobility for cultural consumption. European sociological review, 33(4), 576-589.

- Choudhary, U., P. Jhamb & S. Sharma (2019). Perceptions of consumers towards social media practices used by marketers for creating brand loyalty. Academy of marketing studies journal, 23(1), 1-12.

- Colbert, F. & D.C. Dantas (2019). Customer relationships in arts marketing: A review of key dimensions in delivery by artistic and cultural organizations. International Journal of Arts Management, 21(2), 4-14.

- Colbert, F. & Y. St-James (2014). Research in arts marketing: Evolution and future directions. Psychology and marketing, 31(8), 566-575.

- Cuenca, M.J. (2015). El desarrollo de audiencias jóvenes en el género cultural ópera. Reflexiones en torno a la programación. Cuadernos de gestión, 17(1), 125-146.

- Feldman, K. (2020). Leading the National Gallery of Art during COVID-19. Museum management and curatorship, 20(1), 1-7.

- Germain-Thomas, P. (2018). Arts marketing: A new marketing art. En C. DeVereaux (Ed.), Arts and cultural management: Sense and sensibilities in the state of the field (152-166). New York, USA: Routledge.

- Gómez Hernández, Y., A. Ramos Ramírez & N. Espinal Monsalve (2018). El consumo de artes escénicas en Medellín. Revista de economía institucional, 22(42), 297-323.

- Kaiser, C., A. Ahuvia, P.A. Rauschnabel & M. Wimble (2020). Social media monitoring: What can marketers learn from Facebook brand photos?. Journal of business research, 117(1), 707-717.

- Kolb, B.M. (2013). Marketing for cultural organizations: New strategies for attracting and engaging audiences, third edition. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Kubacki, K. & D. O’Reilly (2009). Arts marketing. En E. Parsons y P. Maclaran (Eds.), Contemporary issues in marketing and consumer behaviour (55-72). Oxford, United Kingdom: Elsevier.

- Kumar, A. & N. Ayedee (2018). Social media tools for business growth of SMEs. Journal of management, 5(3), 137-142.

- Kurochkin, A. & K. Bokhan (2020). Generation of memes to engage audience in social media. CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2566(1), 10-20.

- Le, H., B. Jones, T. Williams & S. Dolnicar (2016). Communicating to culture audiences. Marketing intelligence and planning, 34(4), 462-485.

- Lee, J.W. & Lee S.H. (2019). User participation and valuation in digital art platforms: The case of Saatchi Art. European Journal of Marketing, 53(6), 1125-1151.

- Lehman, K. & M. Wickham (2014). Marketing orientation and activities in the arts-marketing context: Introducing a visual artists’ marketing trajectory model. Journal of marketing management, 30(7-8), 664-696.

- Massi, M. & A. Turrini (2020). Virtual proximity or physical distance? Digital transformation and value co-creation in COVID-19 times. Il Capitale Culturale, 11(1), 177-195.

- O’Reilly, D. & F. Kerrigan (2010). Marketing the arts: a fresh approach. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Parivudhiphongs, A. (2020). COVID-19 – you can’t stop the beat!. Journal of Urban Culture Research, 20(1), 3-9.

- Plattner, S. (1996). High art down home: an economic ethnography of a local art market. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago press.

- Prasad, R.K. & M.K. Srivastava (2021). Switching behavior toward online shopping: coercion or choice during Covid-19 pandemic. Academy of marketing studies journal, 25(1S), 1-15

- Quero Gervilla, M. & R. Ventura Fernández (2011). El compromiso como variable mediadora para la predicción de las futuras intenciones de consumo en los servicios. Una aproximación a los consumidores de artes escénicas en España. Cuadernos de gestión, 11(1), 15-36.

- Ryder, B. (2020). Cultural institutions digital responses to COVID-19 temporary closures. Orlando, USA: Honors undergraduate theses.

- Tepper, S. (2008). The next great transformation: Leveraging policy and research to advance cultural vitality. En S.J. Tepper y B. Ivey (Eds.), Engaging art: The next great transformation of America’s cultural life (363-386). New York, USA: Routledge.

- Thota, S.C. (2018). Social media: A conceptual model of the whys, whens and hows of consumer usage of social media and implications on business strategies. Academy of marketing studies journal, 22(3), 1-12.

- Vega-Gómez, F., F. Miranda-Gonzalez, J. Pérez Mayo, O. González-López y L. Pascual-Nebreda (2020). The scent of art. Perception, evaluation, and behaviour in a museum in response to olfactory marketing. Sustainability, 12(1384), 1-15.

- Walmsley, B. (2016). From arts marketing to audience enrichment: How digital engagement can deepen and democratize artistic exchange with audiences. Poetics, 58(1), 66-78.

- Whiting, L.S. (2008). Semi-structured interviews: Guidance for novice researchers. Nursing standard, 22(23), 35-40.

- Xin, K., C. Wenyin & K. Jian (2019). Art in the age of social media: Interaction behavior analysis of Instagram art accounts. Informatics, 6(52), 1-19.