Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 5

Analysis of the Determinants of Economic Complexity and Economic Diversification in Algeria

Kahina Mellab, Research Center in Applied Economics for Development (CREAD), Bouzaréah, Algeria

Citation Information: Mellab, P. (2025). Analysis of the determinants of economic complexity and economic diversification in Algeria. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(5), 1-24.

Abstract

The complexity of a country's economy is a crucial indicator of its development and competitiveness in the global market. Economic complexity has become a central focus in modern economic research, providing a valuable tool for assessing the production capacity of an economic system. This concept reflects how diverse and sophisticated an economy is in producing a wide range of goods and services. By analyzing the productive knowledge embedded within an economy, particularly through its export structure, economic complexity offers insights into the capabilities of businesses and the workforce. In the context of Algeria, this framework helps to identify the country's potential for diversification, structural transformation, and the development of industries beyond hydrocarbons. By focusing on export diversification and understanding the "product space," this approach provides a clearer view of Algeria's economic capabilities and prospects for sustainable growth and development.

Keywords

Economic Complexity, Algeria, Export Diversification, Structural Transformation, Manufacturing Industries.

Introduction

Algeria's economy, despite nearly two decades of transition towards a market economy, continues to exhibit persistent structural weaknesses. The country remains heavily reliant on hydrocarbons, with the industrial sector contributing less than 5% to GDP. Economic growth has been relatively low and volatile, showing only modest increases in GDP per capita. The Algerian economy also faces underperformance in comparison to international standards and neighboring countries, with average annual GDP growth of just 3.69% from 1961 to 2019 well below that of South Korea, which averaged 7.37% over the same period.

In the 2000’s, rising oil and gas prices enabled the government to implement ambitious economic policies, yet the sharp decline in oil prices post-2014 exposed the vulnerabilities of Algeria’s hydrocarbon-dependent development model. Between 2004 and 2018, oil and gas exports accounted for nearly 96% of exports, 43% of fiscal revenues, and 21% of GDP. These figures highlight the extent of the country's reliance on hydrocarbons. The devaluation of the Algerian dinar from 77.6 DZD to 120 DZD per USD between 2012 and 2019, coupled with the growth of the parallel exchange market (offering a premium of around 60%), further underscores economic instability.

The fiscal and trade deficits worsened in 2019 and 2020, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, the economy contracted by 4.7%, following a meager 0.8% growth in 2019. The pandemic, combined with the oil price slump, led to increased public deficits, with the budget deficit rising from 5.6% of GDP in 2019 to 13.6% in 2020. The current account deficit similarly surged from 10% of GDP in 2019 to 14.8% in 2020, reflecting the country's failure to diversify its export base and its ongoing dependence on costly imports.

From 2020 to 2025, Algeria’s economic performance has been shaped by both external and internal factors. Despite a recovery in global oil prices, which boosted Algeria's energy exports, the country’s reliance on hydrocarbons remains deeply entrenched. By 2022, Algeria became Africa's leading producer of natural gas, but this continues to be a double-edged sword, as global price fluctuations still heavily influence the economy. In 2023, Algeria’s exports reached 46.3 billion USD, with hydrocarbons constituting the majority of this figure. Although non-hydrocarbon exports have increased to about 5 billion USD, the country still faces a significant trade imbalance, with imports amounting to 36.9 billion USD.

Despite these challenges, the government has committed to reducing the hydrocarbons sector's contribution to the national economy by 20% by 2025. This is part of a broader economic diversification strategy that includes promoting entrepreneurship, particularly in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and startups. However, the key to successful diversification lies in the growth of the manufacturing sector, which is seen as the principal pillar of economic transformation and complexity. Manufacturing is crucial not only for diversifying Algeria's economy but also for enhancing its economic resilience. By shifting from a reliance on raw material exports to value-added production, the manufacturing sector can help boost productivity, create jobs, and stimulate innovation.

The manufacturing sector holds the potential to drive long-term economic growth by transforming Algeria into a more diversified and competitive economy. This would reduce vulnerability to external shocks, such as fluctuating global oil prices, and foster greater integration into global value chains. As part of the broader diversification strategy, the government aims to increase the contribution of manufacturing to GDP and create an environment conducive to industrialization, technological advancement, and innovation.

The concept of "structural transformation," as articulated by economist Simon Kuznets, is central to this vision. Kuznets argues that achieving high rates of per capita or worker productivity growth necessitates substantial shifts in the structure of production across sectors. For Algeria, this means fostering growth in sectors such as manufacturing and modern services, which can drive both productivity improvements and higher income levels. Such a transformation would help mitigate the productivity gaps between the country's low-productivity sectors and more dynamic ones, accelerating economic development.

In recent years, Algeria has made progress in promoting industrial and technological innovation, yet its economic structure remains largely dominated by the informal sector, particularly in services and construction. Addressing these imbalances requires comprehensive policy reforms aimed at enhancing the competitiveness of key sectors and reducing reliance on imports.

As of today, Algeria’s economic outlook remains uncertain, particularly as global oil prices continue to fluctuate and the country’s diversification efforts face challenges. The government’s focus on fostering innovation and entrepreneurship in small businesses offers a potential pathway to achieving a more diversified and resilient economy. However, long-term success will depend on effectively implementing these reforms and navigating the structural challenges that have plagued the Algerian economy for decades.

The manufacturing industry is characterized by its pivotal role in economic complexity, as it not only produces high-value-added goods but also fosters innovation and generates spillover effects that enhance productivity and competitiveness across other sectors of the economy.

Despite significant progress in the field of economic complexity, notable gaps remain, especially in measurement. Economic complexity is typically quantified using the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) and the Product Complexity Index (PCI). These indices, initially developed by Hausmann & Hidalgo (2009), were groundbreaking in their approach to understanding the underlying structure of economies. The ECI measures the complexity of a country’s export basket, providing a holistic view that enables cross-country comparisons and serves as an aggregate measure of economic sophistication. In contrast, the PCI focuses on the complexity of individual products or sectors, helping to pinpoint key areas for industrial policy and strategic development (Hausmann & Hidalgo, 2009; Hausmann et al., 2014). The significance of Hausmann’s work lies in its ability to link economic complexity to long-term growth outcomes, showing that nations with more complex export baskets tend to experience higher rates of economic growth and development.

This study adopts the ECI to analyze the determinants of economic complexity in Algeria, taking into account contextual factors and country-specific dynamics that contribute to the nation’s economic transition. The development of the ECI has provided new insights into how countries can move towards more sophisticated economic structures over time, with scholars like Mealy & Teytelboym (2020) & Hartmann et al., (2019) further advancing our understanding of the role of economic complexity in promoting development.

Existing literature highlights a variety of factors influencing economic complexity, which can be classified into domestic and international elements. Among the key determinants are GDP per capita (Agosin et al., 2012; Elhiraika & Mbate, 2014), human capital development (Romer, 1990; Tebaldi, 2011), institutional quality (Costinot, 2009; Strauss, 2015), foreign direct investment (Iwamoto & Nabeshima, 2012; Javorcik et al., 2017), and natural resources (Camargo & Gala, 2017). These factors are critical in understanding how economic complexity evolves, with the interplay of domestic policy, institutional strength, and global trade dynamics shaping the trajectory of economic development.

This study examines these factors to determine whether internal, external, or hybrid influences are driving Algeria's economic complexity. Additionally, it assesses Algeria’s economic structure, focusing on its diversification potential and growth prospects, particularly in light of the country's heavy reliance on hydrocarbon exports. The research further investigates the relationship between economic complexity, technological advancement, economic development, and income inequality. Understanding these connections is crucial for improving Algeria’s global competitiveness and societal well-being.

Recent contributions to the literature have also explored how economic complexity correlates with resilience in the face of global shocks, such as the volatility of commodity prices (e.g., oil) and global financial crises (Hausmann et al., 2014; Mealy & Teytelboym, 2020). These studies show that economies with higher complexity are better able to withstand external economic shocks, as their diversified export baskets allow them to adapt to changes in global demand.

By identifying the key determinants of economic complexity and exploring how it relates to other vital factors, this study aims to inform policy decisions that promote economic sophistication, reduce inequality, and foster inclusive growth in Algeria. Ultimately, the goal is to provide insights that can guide policymakers in diversifying Algeria's economy, reducing dependence on hydrocarbons, and fostering long-term, sustainable growth.

Using time series analysis, Khan et al., (2020) explored the bidirectional causal relationship between economic complexity and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in China. The study measured China’s economic sophistication using the improved Economic Complexity Index (ECI) over the period 1985-2017 and employed the Auto-regressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) framework to estimate the long-term relationship between the variables. The findings revealed a mutual influence between economic complexity and FDI, with economic complexity also having a short-run impact on FDI.

Manuel, Irving, & Fernando (2021) examined the link between economic complexity and FDI distribution among Mexican states, utilizing data from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography. They found that the economic complexity of a state strongly correlated with its ability to attract FDI. Their study also indicated that the complexity of industry groups was a key determinant of the amount of FDI a state received, with strong local spillover effects observed, meaning states with complex neighbors experienced increased FDI inflows.

Yalta & Yalta (2021) studied the determinants of economic complexity in the MENA region, particularly focusing on the role of human capital. Using a system GMM approach and data from 12 countries between 1970 and 2015, they found a positive relationship between human capital and economic complexity. However, natural resource rents were found to have a negative impact, which disappeared when interacting with human capital and democracy. Their study emphasized economic complexity as a tool for helping countries escape the middle-income trap.

Zhu & Li (2017) analyzed the interaction between economic complexity, human capital, and economic growth across 210 countries from 1995 to 2010. They discovered a positive effect of economic complexity and human capital on economic growth, with secondary education having a more significant impact than higher education. The study also found that the positive connection between complexity and human capital on long-term growth was relatively small and sensitive to the sample and The Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) threshold.

Caous & Huarng (2020) explored the link between the Human Development Index (HDI) and Economic Complexity Index (ECI) in emerging economies from 1990 to 2017. They found that greater economic complexity was associated with higher human development, though this relationship was only partially mediated by income inequality. Sustainable development was influenced by energy use and gender inequality, and income inequality reduced the positive impact of economic complexity on human development in developing nations.

Ncanywa et al., (2021) examined the link between economic complexity and income inequality in sub-Saharan Africa, including Nigeria. Using panel data from 1994 to 2017 and the ARDL model, they found that economic complexity was associated with reduced income disparities. The study highlighted the importance of diversifying and upgrading the productive structure, moving beyond primary sectors to reduce the income gap.

Mao & An (2021) conducted an empirical analysis of the nexus between ECI and economic development using data from middle and high-income economies between 1995 and 2010. The study utilized OLS, fixed-effects, and system GMM methodologies and found a positive correlation between ECI and per capita GDP. They noted that a one-unit increase in ECI corresponds to a 30% rise in per capita GDP for these economies. Key drivers for enhancing ECI included increased GVC integration, a robust manufacturing sector, human capital, R&D expenditure, and significant outward FDI stocks.

Ajide (2022) investigated how economic complexity impacts entrepreneurship in selected African countries using data from 18 nations spanning 2006-2017. The study showed that higher economic complexity positively influenced entrepreneurship, with ethnic and religious diversity amplifying this effect, while weak political institutions diminished it. The study emphasized the role of productive knowledge, product mix, and exports in driving entrepreneurship across African nations.

The present study seeks to bridge the gaps in the literature by focusing on the determinants of economic complexity in Algeria using the Economic Complexity Index (ECI), a measure that provides a holistic perspective and enables cross-country comparisons. This research intends to examine the dynamics and transition processes that allow countries to move toward more complex economic structures over time, with a particular focus on Algeria's transition from 2007 to 2023. By analyzing the factors influencing Algeria’s economic complexity, this study aims to offer valuable insights for policymakers and provide recommendations to foster economic sophistication and long-term sustainable development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Economic Complexity Index (ECI) measures a country's economic capacity, which can be inferred from data linking locations to the activities present in those areas. Research has shown that the ECI can predict key macroeconomic outcomes, such as a country's income level, economic growth, income inequality, and greenhouse gas emissions. It has been estimated using various data sources, including trade data, employment data, stock market data, and patent data.

The Product Complexity Index (PCI) assesses the complexity involved in producing a product or engaging in a specific economic activity. The PCI is found to be correlated with the spatial concentration of economic activities (Table 1).

| Table 1 COUNTRIES (ECI) RANKINGS BY ECONOMIC COMPLEXITY INDEX (ECI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| The Top 10 Countries Ranked | The 10 Least Ranked Countries | ||

| Japon | 2,07 | Pakistan | -1,32 |

| Chinese Taipi | 2 | Gabon | -1,41 |

| Switzerland | 1,96 | Yemen | -1,47 |

| South Korea | 1,85 | Cameroon | -1,59 |

| Germany | 1,79 | Burma | -1,61 |

| Singapore | 1,62 | Bangladesh | -1,71 |

| Czechia | 1,6 | Cambodia | -1,72 |

| Austria | 1,56 | Papua New Guinea | -1,72 |

| Sweden | 1,53 | Angola | -1,74 |

| United states | 1,5 | Nigeria | -2,23 |

| Source: OCE | |||

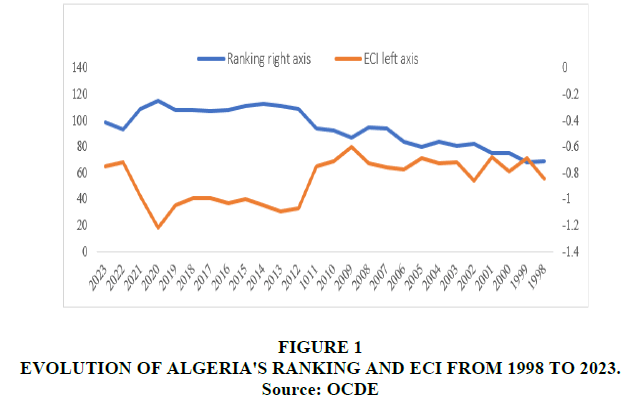

The consistent negative ECI for Algeria over the years reflects its heavy reliance on natural resources, particularly oil and gas, which are typically low-complexity sectors. This dependence hinders economic diversification and restricts growth in more sophisticated industries, such as manufacturing or technology. The 2020 dip in both ECI and ranking can be attributed to the global economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a sharp decline in global oil demand, significantly affecting Algeria’s economy. This also exacerbated existing internal challenges, including fiscal deficits and the lack of industrial diversification. The country’s ranking fell to 115th in 2020, a reflection of thesecompounded issues.

However, the slight recovery in ranking to 99th by 2023 suggests some improvement, but not enoughto significantly alter Algeria's economic position. Despite the recovery, the country’s economy remains underdeveloped and dependent on hydrocarbons, limiting its ability to develop a more complex and diversified economic structure. To improve its ECI and global ranking, Algeria must focus on economic diversification, technological innovation, and infrastructure development, shifting away from its dependency on natural resources and creating a more competitive, sophisticated economy.

Estimating economic complexity involves determining both the complexity of locations (e.g., countries, cities, regions) and the complexity of the activities within them (e.g., products, industries, technologies). The core idea is that the activities produced or exported by a location provide insight into that location's complexity, while the locations where an activity is found reflect the complexity needed to perform it. For example, cities like San Francisco, Boston, and New York are considered complex because they host advanced activities, while activities like biotech or aerospace are seen as complex because they are typically found in sophisticated economies like those of Boston and San Francisco. This concept can be formalized into equations used to estimate the complexity of economies.

Formally, let the complexity K of a location c (e.g., country or city) be and the be a matrix summarizing the activities (p) present in location (c). Complexity K of an activity p (e.g., product or industry) be . Also, let . Usually, is defined as when a location's output in an activity is larger than what is expected for a location ofthe same size and an activity with the same total output. This can be done using an indicator such as a location's Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) or Location Quotient (LQ).

That is, we can define

Where

And Σ Σ

Σx

Following this notation, the general assumption made by metrics of economic complexity is that:

(i)The complexity of a location is a function (f) of the complexity of the activities present in it and (ii) The complexity of an activity of the activities present in it .

This circular logic is equivalent to the following mathematical map.

Where f and g are functions to be determined.

These mappings imply that measures of the complexity of economies or of economic activities, are solutions to self-consistent equations of the form:

Which in many occasions can be reduced-or approximated by-a linear equation of the form:

These equations imply that metrics of the complexity of economies, or of the activities present in them, are respectively, eigenvectors of matrices connecting related countries Mcc or related products (e.g. the Product Space). We note that the first set of equations provide a more general family of functions that includes functions that cannot be reduced to the linear forms, yet, they can provide results that are similar to those obtained by linear equations.

These equations also tell us that measures of complexity are relative measures, since the complexity of a location or an activity can change because of changes in the entries for other locations or activities (other rows or columns in the Rcp or Mcp matrix).

Using this framework, we define the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) of a location as the average Product Complexity Index (PCI) of the activities present there. Likewise, the Product Complexity Index (PCI) of an activity is defined as the average Economic Complexity Index (ECI) of the locations where that activity is found. In other words, the complexity of a location is the average complexity of its activities, and the complexity of an activity is the average complexity of the places where it occurs. Formally, the ECI formula is the solution to the system of equations:

_

- ΣM

- ΣM

Which, upon putting the second equation in the first one, is equivalent to diagonalizing the following matrix: Σ-

Here Mc=Σ is the number of activities (or diversity) of a location and Σ is the ubiquity of an activity (number of locations where it is present).

Since economic complexity is a relative metric, the results are usually normalized using a Z-transform. That is:

-

-

Where is the average of and is the standard deviation of.

The study utilizes an extensive econometric model to examine the impact of various factors on Algeria's economic complexity. Inspired by the approach used by Adegboyega Soliu B, et al. (2024) in analyzing the determinants of economic complexity in Nigeria, and incorporating modifications to fit the Algerian context, the baseline model for analyzing the determinants of economic complexity in Algeria is specified as follows, drawing from the methodology used by Yalta & Yalta (2021):

ECI=F(FDI, CC, GDDPPC, HTX, NRR, TOT, PS, ROL, RQ, GE,)

The econometric model is structured as: Where: ECI represents the Economic Complexity Index, GDPpc stands for GDP per Capita, HTX refers to high-tech exports, NRR denotes Natural Resource Rent, FDI represents Foreign Direct Investment, and TOT refers to Terms of Trade. Additionally, βo represents the intercept, indicating the baseline level of economic complexity, while β1 to β10 are the coefficients of the respective variables, signifying their impact on ECI. ε represents the error term, accounting for unobserved factors influencing ECI that are not included in the model. Table 2 presents the data measurements, descriptions, and sources for the various variables employed in the study.

| Table 2 MEASUREMENT, DESCRIPTION AND SOURCES OF DATA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Description | Measurement | Sources |

| ECI | Economic complexity | Economic complexity index | Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) |

| GDPPC | Gross domestic product per capita | GDP per capita (constant 2015 US$) | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank |

| FDI | The inflow of foreign investments into a country's economy | Percentage of GDP | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank |

| TOT | Terms of trade | The ratio of a country's export prices to its import prices, indicating the economic terms of trade with the rest of the world | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank |

| CC | Control of corruption | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) | |

| GE | |||

| HTX | Technological advancement | Measures a country's technological development based on high-tech exports | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank |

| TOT | Terms of trade adjustment (constant LCU) | The ratio of a country's export prices to its import prices, indicating the economic terms of trade with the rest of the world | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank |

| MFG | Manufacturing, value added (% of GDP) | Percentage of GDP | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank |

| NRR | Total natural resources rents | % of GDP | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank |

| PS | Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) | |

| ROL | Rule of law | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) | |

| RQ | Regulatory quality | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) | |

| TOT | Terms of trade | World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank | |

| Source: Authors compilation (2025) | |||

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Econometric Strategy

To examine the long-run cointegration between economic complexity and its determinants in Algeria, as outlined in equation (3), we apply recent analytical methods, namely Canonical Cointegrating Regression (CCR) and Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS), for the period from 1990 to 2022. These methods are employed in contrast to the ARDL approach used by Adegboyega et al., (2022a & b), Adegboyega, Odusanya & Popoola (2017), Ahmed, Seikdear & Khatun (2022), and Shahbaz & Rahman (2010), who argue that ARDL is most effective in analyzing both long-run and short-run effects when dealing with variables of either I(0) or I(1).

However, CCR and FMOLS are designed specifically to estimate cointegrating relationships between I(1) variables and are more efficient when estimating multiple cointegrating vectors in one step, as suggested by Johansen (1991) & Gonzalo (1994). These methods outperform ARDL in terms of their ability to handle multiple cointegrating vectors simultaneously, offering a more robust estimation framework in cases where complex relationships between variables are expected.

In addition, FMOLS and CCR methods address endogeneity between regressors, a common issue in cointegrated relationships that ARDL does not explicitly control for. This endogeneity correction enhances the reliability of the estimates, as failing to account for it can lead to biased results. Moreover, both methods correct for serial correlation in cointegrated series, which is frequently present in economic data. In contrast, ARDL estimates may still exhibit bias in the presence of serial correlation, even when robust standard errors are used.

Furthermore, FMOLS and CCR provide asymptotic optimality in estimating cointegrating vectors, a feature that ARDL does not possess. This makes FMOLS and CCR particularly advantageous in situations where precise long-term relationships between variables are crucial. These methods are also superior in terms of consistency-FMOLS and CCR estimates of long-run parameters remain super-consistent even with small sample sizes, which is often a limitation of other methods such as ARDL.

Finally, one important feature of both FMOLS and CCR is their ability to correct for small-sample biases, a common problem in econometric analysis, especially when working with time series data. While ARDL can offer valuable insights, its limitations in addressing endogeneity and serial correlation, along with the potential for small-sample biases, underscore the advantage of using FMOLS and CCR in this context for more accurate and reliable long-run parameter estimates.

In summary, by employing FMOLS and CCR methods, this study aims to provide a more accurate understanding of the long-run relationships between economic complexity and its key determinants, offering improved consistency and efficiency over traditional methods like ARDL (Table 3).

| Table 3 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS SUMMARY |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | ECI | FDI | GDPPC | GE | HTX | MFG | NRR | PS | ROL | RQ | TOT | |

| Mean | -0,61 | -1,28 | 0,79 | 8,42 | -0,51 | 15,45 | 8,21 | 21,88 | -1,05 | -0,82 | -1,13 | 25,14 |

| Median | -0,61 | -1,28 | 0,71 | 8,42 | -0,52 | 15,52 | 8,19 | 22,59 | -1,10 | -0,82 | -1,21 | 27,43 |

| Maximum | -0,47 | -0,70 | 1,83 | 8,47 | -0,34 | 16,02 | 10,21 | 32,87 | -0,58 | -0,68 | -0,52 | 27,92 |

| Minimum | -0,67 | -1,72 | -0,29 | 8,37 | -0,67 | 14,61 | 6,28 | 12,82 | -1,36 | -0,94 | -1,39 | -2,30 |

| Std. dev. | 0,06 | 0,26 | 0,50 | 0,03 | 0,09 | 0,40 | 1,23 | 6,05 | 0,22 | 0,07 | 0,25 | 7,25 |

| Skewness | 0,98 | 0,42 | 0,00 | -0,08 | 0,02 | -0,64 | 0,03 | 0,25 | 0,70 | 0,23 | 1,32 | -3,48 |

| Kurtosis | 3,36 | 2,76 | 3,24 | 1,68 | 2,41 | 2,51 | 1,83 | 2,13 | 2,69 | 3,01 | 3,84 | 13,66 |

| Jarque-Bera | 2,80 | 0,53 | 0,04 | 1,25 | 0,25 | 1,34 | 0,96 | 0,71 | 1,46 | 0,14 | 5,41 | 114,83 |

| Probability | 0,25 | 0,77 | 0,98 | 0,54 | 0,88 | 0,51 | 0,62 | 0,70 | 0,48 | 0,93 | 0,07 | 0,00 |

| Sum | -10,32 | -21,75 | 13,46 | 143,17 | -8,68 | 262,63 | 139,53 | 372,04 | -17,87 | -13,96 | -19,24 | 427,37 |

| Sum Sq. dev. | 0,05 | 1,11 | 4,00 | 0,02 | 0,13 | 2,59 | 24,31 | 585,42 | 0,79 | 0,08 | 0,99 | 840,46 |

| Source: Authors compilation (2025) | ||||||||||||

The descriptive statistics in this table reveal key characteristics of the data across multiple variables. The mean values indicate slight negative averages for most variables like CC (Control of Corruption) (-0.61), ECI (Economic Complexity Index) (-1.28), GE (Government Effectiveness) (-0.51), and others, while FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) (0.79) and GDPPC (Gross Domestic Product per Capita) (8.42) show more positive trends. The median closely mirrors the mean, suggesting a relatively symmetric distribution for most variables. Maximum and minimum values highlight the range, with variables like MFG (Manufacturing) having a broad spread between 6.28 and 10.21. The standard deviations vary widely, with some variables like NRR (Natural Resource Rent) (6.05) showing high variability, while others like GDPPC (0.03) are more stable. Skewness values indicate some asymmetry, particularly in variables like ROL (Rule of Law) (1.32) and TOT (Terms of Trade) (-3.48), while kurtosis values suggest differing tail behaviors; for instance, TOT exhibits high kurtosis (13.66), indicating heavy tails. The Jarque-Bera test results show that most variables have a normal distribution, except for TOT, which has a significantly low probability (0.00), indicating a non-normal distribution. Finally, the sum and sum of squared deviations further illustrate the overall trends and variation in the dataset (Table 4).

| Table 4 CORRELATION ANALYSIS |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | CC | ECI | FDI | GDPPC | GE | HTX | MFG | NRR | PS | ROL | RQ | TOT |

| CC | 1 | |||||||||||

| ECI | -0,50401 | 1 | ||||||||||

| FDI | 0,181715 | -0,39885 | 1 | |||||||||

| GDPPC | -0,18724 | 0,072195 | -0,55533 | 1 | ||||||||

| GE | 0,308933 | -0,67435 | -0,10656 | 0,243164 | 1 | |||||||

| HTX | -0,46855 | 0,627013 | 0,219565 | -0,13012 | -0,63134 | 1 | ||||||

| MFG | 0,418036 | 0,006767 | 0,087867 | -0,23115 | 0,129433 | -0,08147 | 1 | |||||

| NRR | 0,483706 | -0,33185 | 0,600464 | -0,64288 | -0,03107 | -0,05256 | 0,520603 | 1 | ||||

| PS | -0,47451 | 0,87644 | -0,46715 | 0,276331 | -0,51773 | 0,567785 | -0,07394 | -0,52961 | 1 | |||

| ROL | 0,47501 | 0,085414 | 0,201541 | -0,36399 | -0,23626 | 0,066718 | 0,373716 | 0,430204 | 0,172859 | 1 | ||

| RQ | 0,145039 | 0,129738 | 0,455848 | -0,58 | -0,3253 | 0,357997 | 0,384557 | 0,650695 | -0,00434 | 0,38818 | 1 | |

| TOT | 0,384134 | -0,15799 | 0,049255 | 0,216118 | 0,146491 | -0,19876 | 0,508774 | 0,451955 | -0,22581 | 0,05216 | 0,28914 | 1 |

| Source: Authors compilation (2025) | ||||||||||||

The correlation matrix offers valuable insights into the relationships between various economic, industrial, and institutional variables. Key takeaways include the moderate negative correlation between Control of Corruption (CC) and Economic Complexity Index (ECI), suggesting that higher levels of corruption control might be linked to lower economic complexity. This could indicate that economic complexity may thrive in more corrupt or less controlled environments, or that the ability to control corruption does not necessarily foster advanced economies. The strong negative correlation between ECI and Government Effectiveness (GE) further supports this idea, highlighting an inverse relationship where a higher ECI is associated with lower government effectiveness.

Conversely, the positive correlations between Natural Resource Rent (NRR) and Manufacturing (MFG) point to a potentially synergistic relationship, implying that greater reliance on natural resources may stimulate manufacturing activities, especially in countries that leverage such resources effectively. The strong correlation between Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and NRR suggests that an increase in foreign investments may bolster net returns from natural resources. Similarly, Regulatory Quality (RQ) and NRR have a significant positive correlation, indicating that high-quality regulations are likely conducive to better utilization of natural resources.

The negative relationships between Political Stability (PS) and both Control of Corruption (CC) and Government Effectiveness (GE) suggest that higher political stability may result in lower corruption and more effective governance, which could indicate a trade-off between these factors or opposing trends in countries with varying political climates.

In general, the matrix reveals important institutional dynamics, where variables like Rule of Law (ROL), Regulatory Quality (RQ), and Political Stability (PS) interact closely with economic and industrial performance, influencing each other in complex ways. However, some correlations are weaker, such as between ROL and PS or ECI and RQ, suggesting that while there are relationships, they are not as impactful in some cases.

Critically, while these correlations suggest meaningful relationships, they do not imply causation. Further research is needed to determine the direction and strength of these effects, and whether these institutional and economic factors directly influence one another or if other underlying variables drive these trends. The correlation matrix serves as a useful starting point for understanding the interplay between economic complexity, industrial output, and institutional quality, but it is important to approach these findings with caution and consider further statistical methods to explore causality (Table 5).

| Table 5 AUGMENTED DICKEY-FULLER UNIT ROOT TEST |

|||||

| Variables | t-Statistique (Level) | p-Value (Level) | t-Statistique (1st difference) | p-Value (1st difference) | Order of integration |

| PS | -2.27773 | 0.4209 | -6.41037 | 0.0007 | I(1) |

| ROL | -1.90181 | 0.607 | -3.7931 | 0.0474 | I(1) |

| RQ | -1.20068 | 0.2513 | -4.57538 | 0.0006 | I(1) |

| TOT | 1.184916 | 0.9996 | -11.342 | 0 | I(1) |

| CC | -2.0345 | 0.2706 | -4.29103 | 0.0054 | I(1) |

| ECI | 0.162451 | 0.9596 | -7.53194 | 0.0001 | I(1) |

| FDI | -2.98788 | 0.1649 | -5.5383 | 0.0027 | I(1) |

| GDPPC | -1.6669 | 0.7181 | -3.14599 | 0.0084 | I(1) |

| GE | -3.29734 | 0.1103 | -5.71153 | 0.0039 | I(1) |

| HTX | -4.31248 | 0.024 | -7.35872 | 0.0003 | I(0) |

| MFG | -2.03413 | 0.5403 | -3.69412 | 0.0583 | I(1) |

| NRR | -2.2906 | 0.4149 | -4.65548 | 0.0113 | I(1) |

|

Source: Authors compilation (2025) |

|||||

The descriptive statistics provide valuable insights into various economic and institutional variables that directly impact Algeria’s performance and development. As an emerging economy, Algeria faces challenges related to Political Stability (PS), governance (ROL), economic complexity (ECI), and other factors. The data highlights issues such as weak control over corruption (CC), low government effectiveness (GE), and a heavy reliance on natural resources (NRR), which can be seen as institutional costs hindering Algeria's economic complexity, structural transformation, and diversification. These institutional weaknesses create barriers to fostering a diversified economy and reducing dependence on hydrocarbons.

The weak institutions, such as low political stability, ineffective rule of law, and poor government effectiveness, make it difficult for Algeria to fully embrace structural transformation. This limits the country's ability to diversify its economy and develop new industries. Moreover, Algeria's high dependence on natural resources and its low levels of High-Tech Exports (HTX) indicate an economy that has not yet fully transitioned to a more complex and sustainable growth model. These institutional costs prevent the diversification of the economy, reinforcing Algeria’s reliance on the oil and gas sector.

The correlation and fluctuation of variables like FDI (Foreign Direct Investment), MFG (Manufacturing), and HTX (High-Tech Exports) are particularly crucial for Algeria's economic future. Growing these sectors is essential to reduce dependence on oil and gas. The high volatility in HTX indicates that technological innovation and export diversification are areas that need more attention for Algeria to move toward a more complex and diversified economy. Additionally, the Terms of Trade (TOT) and Regulatory Quality (RQ) influence Algeria’s interactions with global markets and how effectively internal regulations support economic development.

Given that most of the variables in the data are non-stationary at their levels but become stationary after first differencing, the use of cointegration techniques like FMOLS (Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares) and CCR (Canonical Cointegrating Regression) is justified. These techniques are ideal for variables integrated of order 1 (I(1)), as they account for endogeneity, serial correlation, and provide super-consistent estimates of long-run relationships, even with small sample sizes. This makes FMOLS and CCR particularly suited for analyzing the long-term relationships between the economic and institutional variables in Algeria, providing insights into how these factors shape the country’s economic complexity and development trajectory.

Empirical Results

The results from the Fully Modified Least Squares (FMOLS) regression provide valuable insights into the factors influencing Algeria's Economic Complexity Index (ECI) over the 2008-2023 period. Key variables such as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Government Effectiveness (GE), and Political Stability (PS) show significant relationships with ECI. Specifically, FDI has a negative and significant coefficient (-0.1550, p-value 0.0379), suggesting that increased foreign investment is inversely related to economic complexity in Algeria. This could indicate that Algeria's dependence on foreign capital might hinder its efforts to develop a more diversified and complex economy. Government Effectiveness (GE) also has a negative and statistically significant relationship with ECI (-0.8097, p-value 0.0296), implying that lower government effectiveness may restrict the country’s capacity to foster economic complexity. On the other hand, Political Stability (PS) shows a positive and significant association with ECI (0.7423, p-value 0.0213), underscoring the importance of political stability in supporting the development of a more complex economy (Table 6).

| Table 6 ESTIMATION OF THE DETERMINANT OF ECONOMIC COMPLEXITY IN ALGERIA USING THE FULLY MODIFIED ORDINARY LEAST SQUARES (FMOLS) METHOD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| CC | -0.33255 | 0.436936 | -0.76108 | 0.489 |

| FDI | -0.15503 | 0.050787 | -3.05246 | 0.0379 |

| GDPPC | -1.54388 | 0.974187 | -1.58478 | 0.1882 |

| GE | -0.80969 | 0.244498 | -3.31165 | 0.0296 |

| HTX | 0.100802 | 0.067672 | 1.48957 | 0.2106 |

| MFG | 0.018815 | 0.017647 | 1.066214 | 0.3464 |

| NRR | 0.00496 | 0.007619 | 0.651089 | 0.5505 |

| PS | 0.742318 | 0.201967 | 3.675446 | 0.0213 |

| ROL | -0.50455 | 0.400579 | -1.25956 | 0.2763 |

| RQ | -0.05935 | 0.117696 | -0.5043 | 0.6406 |

| TOT | 0.002471 | 0.004118 | 0.600137 | 0.5808 |

| C | 9.648182 | 8.070449 | 1.195495 | 0.2979 |

| Note: Dependent variable: ECI, Method: Fully Modified Least Squares (FMOLS); Date: 03/11/25, Time: 16:29; Sample (adjusted): 2008 2023; Included observations: 16 after adjustments; Cointegrating equation deterministics: C; Long-run covariance estimate (Bartlett kernel, Newey-West fixed bandwidth=3.0000) Source: Authors compilation (2025) |

||||

Other variables like High-Tech Exports (HTX), Manufacturing (MFG), and Natural Resource Rent (NRR) show no significant effects, suggesting that Algeria's heavy reliance on natural resources and lack of technological diversification may limit its ability to increase economic complexity. Variables such as Rule of Law (ROL) and Regulatory Quality (RQ) were found to have insignificant effects, which may indicate that improvements in legal and regulatory frameworks, while important, do not immediately translate into higher economic complexity. Overall, the model explains a substantial portion of the variation in economic complexity (R-squared=0.9101), with the results indicating that institutional factors, particularly political stability and government effectiveness, are crucial in driving long-term economic transformation in Algeria. These findings justify the use of FMOLS, as the variables in the model are integrated of order I(1), making it appropriate for studying long-term relationships and cointegration among these economic and institutional variables (Table 7).

| Table 7 POST ESTIMATION TEST OUTCOMES (FMOLS) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Statistic | Prob |

| Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey Test (Heteroskedasticity) | 0.978997 | 0.5493 |

| ARCH Test (Heteroskedasticity) | 0.09744 | 0.7595 |

| Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey Test (Residuals) | 1.25009 | 0.6126 |

| White's Test (Heteroskedasticity) | 3.232796 | 0.4125 |

| Jarque-Bera Test (Normality) | 0.63487 | 0.728014 |

| Test Ramsey RESET | 0.7341 | 0.8887 |

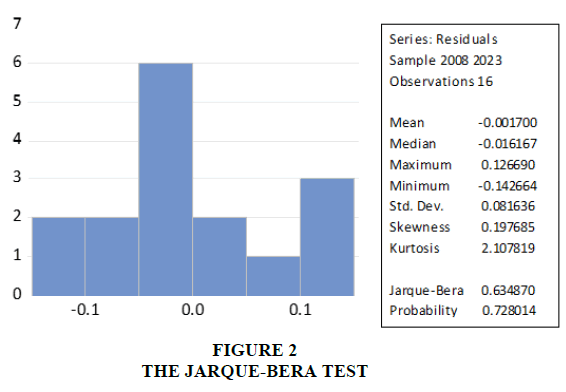

The model validation shows positive results overall. The heteroscedasticity tests (Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey, ARCH, and White’s test) all suggest no significant issues, with p-values above 0.05, indicating that the residuals have constant variance. The Jarque-Bera test for normality also shows a p-value of 0.728, suggesting that the residuals are normally distributed, which is important for the validity of hypothesis tests. The Ramsey RESET test gives a p-value of 0.8887, indicating no specification errors or omitted variables in the model. While some variables in the regression show high p-values, suggesting they may not be statistically significant, the model itself is robust and correctly specified. Overall, the model seems reliable, with no major issues identified, although refinement in variable selection could enhance its explanatory power (Figure 2).

The Jarque-Bera test for normality shows a test statistic of 0.634870 with a p-value of 0.728014, indicating that the residuals are normally distributed. The skewness is 0.197685, suggesting slight positive skew, and the kurtosis is 2.107819, indicating lighter tails than a normal distribution. The mean and median are close to zero, with the standard deviation at 0.081636, suggesting that the residuals are centered and not extreme. Overall, the residuals appear to be approximately normally distributed (Table 8).

| Table 8 ESTIMATION OF THE DETERMINANT OF ECONOMIC COMPLEXITY IN ALGERIA USING CANONICAL COINTEGRATING REGRESSION (CCR) METHOD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. error | t-Statistic | Prob |

| CC | 0.871618 | 1.319212 | 0.660712 | 0.5449 |

| FDI | -0.23686 | 0.124237 | -1.90655 | 0.1293 |

| GDPPC | -8.77644 | 4.294998 | -2.04341 | 0.1105 |

| GE | 2.023028 | 1.409722 | 1.435054 | 0.2246 |

| HTX | 0.277063 | 0.309138 | 0.896245 | 0.4208 |

| MFG | -0.12431 | 0.086993 | -1.42894 | 0.2262 |

| NRR | 0.045092 | 0.025128 | 1.794514 | 0.1472 |

| PS | 1.771246 | 0.912056 | 1.942038 | 0.1241 |

| ROL | -2.63164 | 1.511234 | -1.74138 | 0.1566 |

| RQ | -0.79308 | 0.370647 | -2.13972 | 0.0991 |

| TOT | 0.017603 | 0.014535 | 1.211122 | 0.2925 |

| C | 68.45566 | 36.56231 | 1.872301 | 0.1345 |

| Note: Dependent Variable: ECI; Method: Canonical Cointegrating Regression (CCR); Date: 03/11/25, Time: 16:38; Sample (adjusted): 2008 2023; Included observations: 16 after adjustments; Cointegrating equation deterministics: C; Long-run covariance estimate (Bartlett kernel, Newey-West fixed bandwidth=3.0000) |

||||

The results obtained from the Canonical Cointegrating Regression (CCR) provide insights into the relationships between the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) and several economic and institutional variables of Algeria from 2008 to 2023. Unlike the results derived from the Fully Modified Least Squares (FMOLS) method, the CCR results show that most variables have a weaker relationship with the ECI, suggesting a limited explanation of Algeria's economic complexity.

Key variables such as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Government Effectiveness (GE) show either negative or positive effects but are not statistically significant, with coefficients of -0.2369 and 2.0230, respectively, and p-values greater than 0.05. This indicates that, although these variables are essential in analyzing economic development, their direct impact on economic complexity is not strong enough to be statistically significant in the CCR model. Similarly, Political Stability (PS), while showing a positive coefficient, has an insignificant relationship, with a p-value of 0.1241.

Other variables, such as High-Tech Exports (HTX), Manufacturing (MFG), Regulatory Quality (RQ), and Rule of Law (ROL), also do not show any significant relationship with the ECI, highlighting the absence of structural transformation in Algeria’s economy in terms of diversification. The low significance of both institutional and economic variables reflects a lack of integration of factors such as technological innovation and industrial diversification in the economic growth process.

Algeria, as an economy heavily reliant on hydrocarbons, faces major challenges regarding diversification and economic complexity. Weak governance, legal frameworks, and political stability serve as obstacles to the development of new industries and the structural transformation necessary to diversify the economy and reduce dependence on natural resources. The limited integration of high-tech exports and manufacturing sectors indicates that there is still considerable work to be done to transform the economy and stimulate new sectors in order to reduce reliance on hydrocarbons.

The weak fit of the CCR model (low R-squared and negative adjusted R-squared) suggests that the institutional and economic variables do not fully explain Algeria's economic complexity. This implies that alternative models or the inclusion of additional variables are necessary to better understand the underlying dynamics of the country's economic transition and to develop policies that will foster diversification, competitiveness, and innovation.

Interestingly, both models FMOLS and CCR yielded similar conclusions regarding the relationships between institutional and economic variables and the Economic Complexity Index (ECI). In both models, key variables such as FDI, GE, PS, and MFG showed weak or insignificant relationships with ECI. However, while the FMOLS model provided more statistically significant coefficients (for instance, Government Effectiveness and Political Stability), the CCR model generally showed weaker relationships, with most variables not being significant at the standard levels.

Both models, however, failed to show strong evidence of the economic complexity and structural transformation needed for diversification in Algeria, particularly in relation to high-tech exports (HTX) and manufacturing (MFG). The lack of significant results in the CCR model (with low R-squared and negative adjusted R-squared) aligns with the weaker findings in FMOLS regarding certain institutional and economic variables.

The use of both the FMOLS and CCR models allows for a more comprehensive analysis of Algeria’s economic complexity. The FMOLS model, being robust to non-stationary time series data, provides stronger and more statistically significant results, especially regarding the relationships between key variables like FDI, GE, and PS with ECI. This model captures long-term relationships effectively and offers valuable insights into the factors influencing Algeria's economic structure and complexity.

On the other hand, the CCR model offers a different perspective, particularly focusing on the cointegration of variables over the long term. While it may not yield significant results for most of the variables in this case, it provides an alternative approach to studying the long-term equilibrium relationships between variables and serves as a complement to FMOLS by providing additional insights into the potential structural challenges Algeria faces. The combination of both models enhances the robustness of the analysis and offers a more nuanced understanding of the factors affecting Algeria's economic transition, supporting the development of more informed policy recommendations for achieving economic diversification and sustainable growth (Table 9).

| Table 9 POST ESTIMATION TEST OUTCOMES (CCR) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Tests | Statistics value | Probability |

| Test de Jarque-Bera (Normalité) | 0,44 | 0,802 |

| Ramsey RESET Test | 0.364 | 0.572 |

| Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM Test | 26.616 | 0.004 |

| Heteroskedasticity Test: Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey | 1.395 | 0.375 |

| Heteroskedasticity Test: ARCH | 6.863 | 0.02 |

| Heteroskedasticity Test: ARCH | 6.863 | 0.0201 |

| Source: Authors compilation (2025) | ||

Based on the post-estimation tests, the robustness of the CCR model can be assessed. The Jarque-Bera test for normality indicates no significant deviation from normality in the residuals (p-value=0.8024), suggesting the model’s residuals are normally distributed. The Ramsey RESET test (p-value0.5726) shows no evidence of model misspecification, implying the model is correctly specified. However, the Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM test (p-value=0.0049) reveals the presence of serial correlation, which could undermine the model's robustness by violating the assumption of independent errors. Additionally, while the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey test for heteroscedasticity (p-value=0.3759) suggests no heteroscedasticity, the ARCH test (p-value=0.0202) indicates the presence of conditional heteroscedasticity, which could affect the efficiency of the estimates. Overall, while the model appears robust in terms of normality, specification, and classical heteroscedasticity, the presence of serial correlation and conditional heteroscedasticity suggests the need for further refinement to ensure the robustness of the estimations (Figure 3).

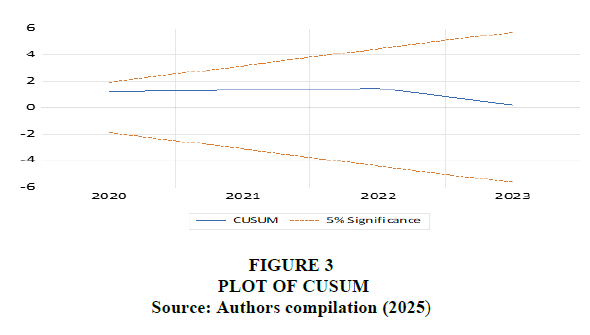

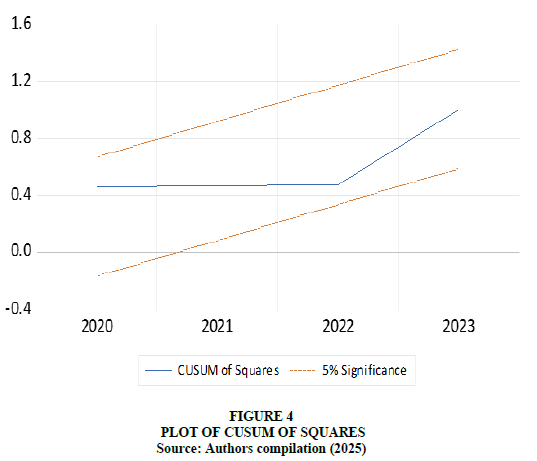

In Algeria, where economic and political conditions, such as fluctuations in oil prices, policy changes, and government transitions, can change rapidly, the CUSUM and CUSUM of Squares tests are essential for assessing the stability of regression model coefficients. If the plots of these tests show that the cumulative sum of recursive residuals and the sum of squared residuals remain within the critical lines at the 5% significance level, it suggests that the model's coefficients are stable despite the dynamic environment. This stability indicates that the relationships between variables have not been significantly affected by external factors. However, if the CUSUM plot crosses the critical lines, it would signal structural breaks or shifts in economic dynamics, requiring adjustments or revisions to the model to better capture these changes (Figure 4).

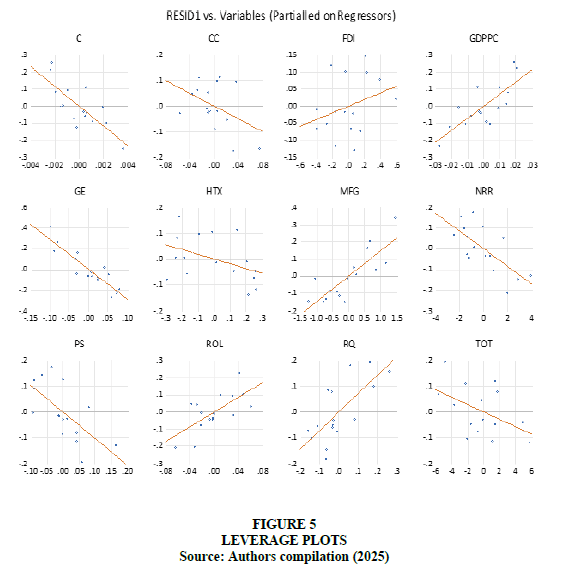

The results of the validation tests, including the CUSUM tests, show that the model coefficients exhibit stability in Algeria, indicating the absence of substantial structural breaks throughout the study period, despite ongoing economic and political changes (Figure 5).

The impact of exchange rates, FDI, and PS (GDP or other relevant variables) on Algeria's Economic Complexity Index (ECI) is significant, with these variables showing considerable dispersion. Volatile exchange rates can affect the competitiveness of Algeria’s exports, influencing the ECI by either promoting or limiting diversification. FDI plays a crucial role in diversifying the economy, but its effect on the ECI depends on whether it targets advanced sectors or remains concentrated in natural resources. Similarly, the country's GDP growth (PS) can impact the ECI, with sustained growth fostering diversification and enhancing export sophistication. The observed dispersion in these variables suggests that their effects on the ECI are non-linear and sensitive to external factors, such as oil price fluctuations or policy changes. Effective management of these factors could lead to greater economic diversification and improved ECI, essential for Algeria’s long-term development.

CONCLUSION

This study has highlighted the crucial role of economic complexity and institutional factors in Algeria’s efforts to diversify its economy and achieve sustainable development. The analysis of economic complexity (ECI) in relation to institutional and economic variables reveals that Algeria faces considerable challenges due to its dependence on hydrocarbons and weak institutional frameworks. Variables such as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Government Effectiveness (GE) show some influence on economic complexity, but many institutional factors, such as Rule of Law (ROL) and Regulatory Quality (RQ), have a limited or non-significant impact. These findings underline the need for Algeria to address structural weaknesses and focus on transforming its economic base from a reliance on natural resources to a more diversified, complex, and competitive economy.

The results obtained from the Fully Modified Least Squares (FMOLS) and Canonical Cointegrating Regression (CCR) models provided complementary insights. FMOLS identified significant effects of some variables like FDI and GE on economic complexity, while the CCR model showed weaker correlations, emphasizing the complexity of Algeria’s economic structure. The differences in results across the two models highlight the importance of using multiple methodologies for a comprehensive analysis of the country’s economic transformation.

RECCOMENDATIONS

Strengthen Governance and Institutions: Algeria must prioritize strengthening institutional frameworks, including improving political stability, the rule of law, and regulatory quality. These institutional reforms are essential for creating an environment conducive to attracting investment, fostering innovation, and driving economic diversification.

Encourage Technological Innovation and Export Diversification: A key avenue for diversification is the promotion of high-tech exports and investments in technological innovation. Encouraging research and development (R&D) and fostering partnerships between the government, private sector, and academic institutions can support the development of a knowledge-based economy and facilitate the growth of industries outside of hydrocarbons.

Promote Sectoral Diversification: Algeria must accelerate its efforts to diversify its economy by reducing its reliance on oil and gas. Sectors such as manufacturing, renewable energy, information technology, and services should be prioritized to build a more resilient and sustainable economic base.

Focus on Human Capital Development: Developing a skilled workforce through education, training, and investment in human capital is essential for supporting a diversified economy. Policies should focus on improving the education system, enhancing technical skills, and providing vocational training to meet the demands of emerging industries.

Create a Conducive Environment for Private Sector Growth: The private sector should be incentivized to invest in diverse industries. This includes offering financial incentives, simplifying regulations, and providing entrepreneurial support to stimulate the development of new sectors beyond hydrocarbons.

Structural Economic Reforms: Comprehensive structural reforms in Algeria’s industrial policies, financial systems, and trade policies are necessary to facilitate diversification. The government must also focus on reducing dependency on external oil and gas revenues by enhancing domestic industries and creating a favorable environment for foreign investment.

To further understand the dynamics of Algeria’s economic diversification and complexity, additional determinants need to be studied. Future research could focus on the role of financial market development, trade policies, and regional integration in diversifying Algeria's economy. The effect of entrepreneurial ecosystems and SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises) in driving industrial growth and innovation could provide valuable insights into alternative paths for diversification. Moreover, examining the impact of climate change and renewable energy as new sectors for growth could be crucial for long-term economic sustainability.

Further analysis could include a deeper dive into sector-specific contributions to economic complexity, particularly in sectors such as agriculture, services, and technology. Understanding how sectoral policies and global value chains interact with national policies would help policymakers better align Algeria’s diversification strategies with global economic trends. Additionally, applying dynamic panel data models or exploring the impact of institutional quality over time using longitudinal data may reveal more nuanced relationships between institutional reform and economic complexity in Algeria. By employing these approaches, researchers and policymakers can develop a more robust understanding of how to accelerate Algeria’s economic transformation toward greater diversification and sustainability.

In conclusion, the road to economic diversification in Algeria is multifaceted and requires a combination of institutional reforms, innovation, private sector growth, and investment in human capital. By addressing these areas, Algeria can overcome its dependency on hydrocarbons and pave the way for a more diversified, competitive, and sustainable economy.

References

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369-1401.

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (2009). The economics of growth. MIT Press.

Ait-Hamouda, A., & Lahlou, M. (2017). The challenges of economic diversification in Algeria: An analysis of economic policies. International Economic Review, 54(1), 98-115.

Arvis, J. F., & Shepherd, B. (2010). The Asia-Pacific trade agreement: The key to economic diversification. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5238.

Ayadi, R., & Benhamed, K. (2017). The transition to a post-hydrocarbon economy in Algeria: What role for industrial diversification?. Algerian Journal of Economics and Management, 12(1), 15-29. Benabdallah, H., & Oulmane, L. (2020). Trade policy and economic diversification in Algeria. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 15(3), 122-138.

Benhamou, S. (2011). Economic diversification and competitiveness of the Algerian economy: Issues and perspectives. Journal of Development Economics, 19(2), 215-242.

Bensid, S., & Khellaf, D. (2016). The role of foreign direct investment in economic diversification: The case of Algeria. Review of International Studies, 31(2), 44-59.

Benziane, M., & Benmahammed, M. (2016). The impact of institutional governance on economic diversification in Algeria. Journal of Economics and Business, 38(4), 249-267.

Birkley, E., & King, G. (2019). Innovation, competitiveness, and economic growth: The role of economic complexity in the 21st century. Economic Development Quarterly, 33(4), 320-333.

Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2011). Technological relatedness and regional branching. Research Policy, 40(5), 1077-1087.

Boudiaf, F., & Souilah, M. (2019). The competitiveness of non-oil sectors and the process of economic diversification in Algeria. Journal of Development Economics, 43(1), 118-134.

Bouras, A., & Mezaoui, S. (2014). Economic governance in Algeria: Towards better management of natural resources and sustainable economic diversification. International Review of Economics and Finance, 35, 83-102.

Chahid, A. (2020). Institutional factors and economic competitiveness in Algeria. Journal of Political and Economic Sciences, 41(2), 115-130.

Daoud, M. (2012). Economic reforms and the competitiveness of the manufacturing industry in Algeria. Algerian Journal of Economic Studies, 27(2), 80-98.

Easterly, W. (2001). The elusive quest for growth: Economists' adventures and misadventures in the tropics. MIT Press.

FDI and Economic Growth (2008). Foreign direct investment and its role in economic growth: A case study of the Algerian economy. Algerian Journal of Economic Studies, 34(2), 112-130.Haddad, A. (2018). Economic diversification in the face of the hydrocarbon crisis: The challenges for the Algerian economy. Economy and Society, 22(2), 55-72.

Hamel, J. (2014). Diversification and economic reforms in Algeria: A comparative analysis with other oil economies. Journal of Development Economics, 56(4), 112-130.

Hausmann, R., & Klinger, B. (2006). Structural transformation and patterns of comparative advantage in the product space. CID Working Paper No. 128. Center for International Development at Harvard University.

Hausmann, R., & Klinger, B. (2011). The product space and the evolution of comparative advantage. The Economic Journal, 121(551), 413-445.

Hidalgo, C. A., Klinger, B., Barabási, A.-L., & Hausmann, R. (2007). The product space conditions the development of nations. Science, 317(5837), 482–487.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Imbs, J., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Stages of diversification. American Economic Review, 93(1), 63-86.Imbs, J., & Wacziarg, R. (2012). The evolution of stages of diversification. Journal of Economic Growth, 17(1), 1-43.

Klinger, B., & Hausmann, R. (2009). The structure of the product space and the evolution of comparative advantage. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5122.

Le Gall, R. (2009). The structure of the Algerian economy and the challenges of sustainable development. Notebooks of Economics and Management, 22(3), 225-240.

Levine, R., & Zervos, S. (2003). Stock markets, banks, and economic growth. World Bank Economic Review, 17(1), 209-236.

Mokhtari, M., & Tadj, A. (2021). Economic diversification strategies in Algeria: The role of infrastructure and economic policy. Journal of Development Studies, 36(3), 80-97.

Montalvo, J. G., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2005). Ethnic diversity and economic development. Journal of Development Economics, 76(2), 293-323.

Nguyen, T. D., Aung, Z. M., & Tran, D. P. (2021). The role of economic complexity in driving growth and development: A cross-country study. Journal of Economic Development, 46(3), 1-17.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

Rodríguez, F., & Rodrik, D. (2001). Trade policy and economic growth: A skeptic’s guide to the cross-national evidence. NBER Working Paper No. 7081. National Bureau of Economic Research. Rodriguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034-1048. Rodrik, D. (2014). The globalization paradox: Democracy and the future of the world economy. W.W. Norton and Company. Roudi, F., & Douai, M. (2016). The effect of fiscal policy on Algeria's economic diversification. Journal of Economic Policy, 9(1), 45-61. Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (1995). Natural resource abundance and economic growth. NBER Working Paper No. 5398. National Bureau of Economic Research.Sadi, I. (2018). Hydrocarbon dependence and economic diversification policy in Algeria: Towards a sustainable strategy?. Economy and Development, 27(3), 40-56.

Vial, S. (2019). Natural resources and the energy transition: Challenges for Algeria. Energy Policy, 132, 190-199.

World Bank. (2020). World development indicators. World Bank.

Zerhouni, R., & Benali, K. (2018). Structural challenges of the Algerian economy in the face of globalization: Diversification and growth strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 18(3), 80-101.

Zouari, L. (2020). The impacts of industrial diversification on the economic development of Algeria: An empirical study. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 10(1), 74-89.

Received: 09-May-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-15769; Editor assigned: 14-May-2025, Pre QC No. AMSJ-25-15769 (PQ); Reviewed: 28-May-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-15769; Revised: 02-June-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15769 (R); Published: 30-Jun-2025