Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 2

Consumer Evaluation of Private Label Branding Strategies

Anant Ram Sudhagani, Institute of Management Technology Nagpur, India

Abstract

Private label brands (PLBs) have emerged as a global phenomenon and have created considerable interest among the scholars and practitioners. They have become a serious threat to national brands. Retailers regularly introduce PLBs to compete with national brands and other rival retail chains. While introducing a new product should retailers use an extended brand or a new brand? The existing branding theories do not provide a ready answer in the private label context. This study attempts to answer the question which launching strategy- extended brand or new brand- is effective in terms of eliciting favorable evaluations from customers? A quasi-experimental design was adapted to test the hypothesis that extended brand name will be more favorably evaluated than new brand name. The main independent variable branding strategies which is in two levels as Extended brand (E) and New brand (N), was paired with a blocking variable namely product type in two levels as Functional (F) and Prestige (P) product. These four experimental treatments (EF, EP, NF, NP) were manipulated by writing suitable brand descriptions and were presented to a random sample of 275 shoppers for evaluation. The evaluations were captured by a 7 item scale involving cognitive, affective and behavioral dimensions. A 5-point rating scale was used to record the responses. A 2x2 factorial ANOVA was performed to analyses the responses. The F ratios for branding strategies (F 1,271 = 3.902; p = 0.049), and for product types (F 1,271 = 7.890; p = 0.005) are significant beyond 5% level and the interaction (F 1,271 = 0.155; p = 0.694) is not significant. The results of this empirical study indicate that, in general, consumers evaluate brand extensions of private labels more favorably. The central contribution of this research is that Private label Extension (PLE) strategy appears to be more viable than new private label (NPL) strategy for retailers. While launching new products, retailers must consider brand extension as a vital guiding strategy since consumers respond more favorably to it.

Introduction

The growth of private label brands (PLBs) represents one of the significant trends in marketing in the recent decades. They emerged as a global phenomenon (ACNielsen 2005, Herstein & Gamliel, 2004, Sethuraman & Gielens, 2014) and will continue to be an enduring feature of FMCG sector (Ansellmsson & Johansson,2009).PLBs constitute 15% of the sales of fast moving goods worldwide, including 17% in the United States (AC Nielsen, 2010) and more than twice this figure in some European countries (eg., Switzerland at 46%, United Kingdom at 43%).In India, PLBs constitute 12% of the total retail product mix and are expected to grow substantially (KPMG India Report 2009).This will continue because they are part of the growth of the economy (AC Nielsen 2018). The increasing dominance of PLBs has led to the shrinkage of retail space for national brands. They have become a strong competitive threat to national brands (Bao et al., 2011) and possess the power to push them off the shelves if they are not leaders in their product categories (Lambin et al., 2007). Conventional wisdom holds that only manufacturer brands convey an emotional value (Tsai, 2005). However, the introduction of PLBs into mainstream categories which are bought for psychological reasons is challenging this view. Indeed, PLBs can increasingly be found in hedonic product categories such as cosmetics and clothing (AC Nielsen, 2005) suggesting that consumers seeking high levels of emotion-related utility can gain it by buying PLB (Broad bridge and Morgan, 2001). PLBs are now ubiquitous. You can now find them in almost all categories sold at the retail level (Herstein, Efrat and Jaffe, 2011).

Retailers employ PLBs as strategic tools to improve their profitability and increase their market share (Kumar & Steenkamp, 2007). Infact, they market PLBs because they yield higher profit margins than national brands (Sethuraman & Gielens, 2014). They also take advantage of positive associations with national brands by imitating their brand names, logos and packaging (Aribarg et al., 2014). They also use PLBs to create Competitive advantage over other retail chains (Ansellmsson & Johansson, 2009) and enhance customers’ preference towards their stores (Steenkamp & Dekimpe, 1997, Kumar & Steenkamp, 2007)

Customers buy PLBSs due to their comparable quality with national Brands and lower prices (10 to 40%) (Halstead & Ward, 1995). In fact, more than 70% of US and European consumers consider PLB quality to be at least as good as the usual big brands (AC Nielsen, 2005). Moreover, most major retailers have their own up market private labels which are hugely successful, such as: Tesco’s Finest range, Co-op’s Truly Irresistible range and Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference range (Walsh & Mitchell, 2010). For example, the Tesco’s Finest range has become one of the UK’s top grocery brands with sales of ?1.2bn ($1.95bn) (Sampson, 2008). Customers now have positive purchase intention towards PLBs due to their increased quality. This enhanced PLB quality and reputation enables consumers to feel good about looking at and making judgments about their own behavior in purchasing PLBs (Arnould, Price and Zinkhan, 2004).

The new higher-quality generation of PLBs with a reputation that is better than many national brands means that some of them now provide social utility and are recognized for their quality, price and indulgence (Walsh & Mitchell, 2010). Also, Customers feel more assured buying a familiar store brand than an unfamiliar minor national brand (Mc goldrick & Marks, 1987).Therefore, retailers regularly introduce PLBs at lower prices compared to national brands but with quality that matches them or slightly beneath (Berman & Evans, 2001). While introducing new product should retailers use an extended brand or a new brand? The existing branding theories do not provide a ready answer in the private label context. This treatise attempts to find a reasonable answer. It probes whether the branding theory developed for national brands holds good for private label brands.

Theoretical Concepts and Hypothesis

In the last two decades, the concepts of brand have created considerable interest among both academicians and practitioners (Aaker & Keller, 1990; Keller, 1993, Klink & Athaide, 2009; Martinez & Chernatony, 2004). Brands facilitate in differentiating and positioning a company’s products (Bhat & Reddy, 1998; Martinez & Chernatony, 2004; Park et al., 1986). They also help in maintaining an enduring relationship with its consumers (Aaker, 1991; Dens & Pelsmaker, 2010; Kotler et al., 2009), and serve as launch pads for new products (Ambler and Styles, 1997; Klink & Athaide, 2009; Seltene & Brunel, 2008; Tauber, 1981). A new product’s brand name is a major determinant of its success in the market place. While introducing a new product, brand names aid in increasing awareness and creating a favorable image. During the launch, companies have either gone in for a new brand name or have extended their existing brand into a different category (Ambler & styles, 1997; Klink & Athaide, 2009).

While choosing an appropriate branding strategy companies evaluate the pros and cons associated with using a brand extension or a new brand. Brand extension involves the use of an established brand name to enter a new product category (Aaker & Keller, 1990). Brand extensions involve lower marketing and brand development costs (Smith & Park, 1992), reinforce the original brand image (Aaker, 1990) and boost parent brand choice (Balachander & Ghose, 2003). But brand extensions have to bear with the disadvantages of having only short -term marginal gains for the company and diminishing consumers’ feelings about the innovation in case of perceived inconsistency between the original and new product categories (Aaker & Keller, 1990; Klink & athaide, 2009); Martinez & Pina (2003) warn that use of brand extension strategy to introduce new products to the market might dilute the brand image of the product. It may also provoke competing firms to launch a counter extension into the Brand’s original category (Kumar, 2005). Another approach to introduce a new product to the market is opting for a new brand name (Ambler & Styles, 1997). Rogers (2003) emphasized that consumers would respond differently to new products due to consumer innovativeness.

Consumer innovativeness refers to one’s propensity to adopt new ideas or products relatively earlier than other members of a social system. According to Klink & Athaide (2009) it is positively related to new product evaluation for new and extended brand names. Since new brand names bear more risk and uncertainty than extended ones, more innovative consumers (high on consumer innovativeness) may accept them faster (Rogers, 2003). New products with warranties, guarantees, seals of approval etc. also enhance consumer confidence and later adopters may like them (Klink & Athaide, 2009). However, managers have often used an existing brand to enter new product categories hoping to leverage the trust in the brand to reduce introduction costs, assuming that consumers prefer brand extensions over new brands (Kane, 1987; Pitta & Katsanis, 1995). Nevertheless, consultants have questioned this practice, claiming that the novelty of new brands can be appealing and that while new brands may implicate greater up-front advertising costs; these costs are offset by risk spread and lesser chances of diluting the brand’s image (Quelch & Kenny, 1994).

Customer reaction to Extended versus New Brand name

Consumers cite various reasons for preferring extended brands over new brand names (Smith & Park, 1992). Extended brands bring down the perceived purchase risk as they are attached with existing brand name (Roselius, 1971). They increase brand recognition, provide quality cue (Bellizzi & Martin, 1982) and act as decision making heuristic (Alba & Huthison, 1987). They also leverage the advertising spillover effects from other products affiliated with the brand. That means, advertisements of other products associated with the brand may strengthen the brand image, hence stimulating demand for the new extension (Klink & Athaide, 2010). Parent brand’s awareness, credibility and reputation play a key role while consumers purchase a brand extension (Aaker & Keller, 1990; Dacin & Smith, 1994; Park et al., 1991). They highlight the importance of the impact of the experience with the parent brand on consumer attitude toward brand extension. Better the previous belief, positive is the brand’s evaluation. Kaur & Pandit (2015) in their India study assert that consumers with strong trust in parent brand have favourable attitude towards its extension. A highly reputed brand acts as a rejuvenator and risk reducer and therefore creates higher product trial (Keller, 2009). A new brand name will not have this inherent advantage and it has to build the brand image from the very foundation.

When a brand with high credibility is extended to a product category considered as risky, the parent brand acts as a risk reducer and clues positive quality and therefore increases its acceptance among consumers (Dacin & Smith, 1994). Though prior researches have studied the consumer evaluation of branding strategies, there is scant research concentrating specifically on consumer evaluation of private label brand strategies (Dwivedi & Merrilees, 2013, Mitchell & Chaudhary, 2014). Hence, the current study intends to address this gap. It specifically aims to examine the impact of branding strategies on consumer attitudes and purchase intention for new products offered by retailers. As discussed earlier, drawing from the well established theoretical concepts developed for national brands the author postulates the following hypothesis:

H1: Consumers evaluate an extended brand name from a private label more favorably than a new brand name (new private label).

Methodology

A quasi-experimental design was adapted to test the hypothesis. The major independent variable of the study is branding strategy. This variable is varied in two ways as extended branding strategy (E) and new branding strategy (N). Since the effectiveness of the branding strategy could be influenced by the type of product, the type of product is included as a blocking variable in order to control its effect on branding strategy. Type of product is varied in two levels as functional product (F) and prestige product (P). Four experimental treatments (EF, EP, NF, and NP) were created and manipulated by writing suitable brand descriptions. Under each of these experimental treatments, sufficient number of consumers was included and their evaluative ratings on the brand described under that treatment condition was captured by a survey questionnaire. This design not only blocks the effect of product type on branding strategies but also enables to estimate the effect of product type and the interaction of branding strategy and product type on customer evaluation. Though we do not have specific hypotheses on product type effects and the interaction effects, we can derive additional insights on the private label branding strategies.

Manipulation of Independent Variables

As indicated, the experimental treatments were manipulated by specific descriptions of brands in each of the four experimental conditions. For doing this, we first created four fictitious brand names. We have conducted a series of pre-tests to identify suitable fictitious brands. All these studies were conducted on s shopper population using quantitative (questionnaire with rating scales) and qualitative (focus group) methodologies. Actual shoppers from two metro cities formed the sample set for these studies. They were asked to rate on a 7-point differential scale various randomly chosen brands and products on perceived quality, distinctiveness and preferences.

Five such pre-testings studies were conducted for various purposes such as, study 1: to identify major functional and prestige products to generate brand names, study 2: to identify PLBs under functional product category, study 3: to identify PLBs under prestige product category, study 4: to identify distant categories of products under functional and prestige PLBs, and study 5: to generate fictitious brand names for new branding strategy using focus groups of students and shoppers.

Atta (Hindi word for Indian Wheat flour used for making south Asian breads flat breads like Chapatti, Naan, Roti and Puri) and apparel were identified as major functional and prestige products around which to generate product and brand names. Under functional product category, Big Bazaar’s atta brand ‘Fresh & Pure’, and under prestige product category, Shoppers Stop’s apparel brand ‘Stop’ were identified as PLBs on which to attach products. Fruit Juices and perfumes were identified as products which are distant from their respective products in functional (Atta) and prestige (apparel) products.

For the experimental condition-extended branding strategy for functional product category ‘Fresh & Pure’ - fruit juice and for prestige product category ‘Stop’ - perfume were generated.

For experimental condition new brand strategy fictitious brands names were generated using focus groups. For functional product category ‘Sip it’- fruit juice and for prestige product category Jarvis - perfume were generated.

The following table shows the experimental conditions and the brand names used under each condition in Table 1.

| Table 1 The Experimental Conditions and the Brand Names Used Under Each Condition | ||

| Functional | Prestige | |

| Extended brand | Fresh and pure – fruit juice | Stop - perfume |

| New brand | Sip it – fruit juice | Jarvis - perfume |

Measurement of Consumer Evaluation

Customer evaluation was measured using a 7 item scale frequently used in the studies in branding literature. (Klink & Athaide, 2010; Steen Kamp et al., 2003; and Dacin & Smith, 1994) These seven items represent a mix of cognitive and affective and behavioral dimensions of attitudes used for evaluation. They represent favorableness, intention to buy, liking, knowledge, desire, familiarity and likelihood to buy. Each of these attributes were converted into a statements and attached a 5-point rating scale ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). The sum of the seven items was treated as the score for consumer evaluation. The factor structure and the reliability of this seven items questionnaire were pretested on a random sample of 119 shoppers.

The factor structure is unidimensional and all seven items load on one factor which accounts for 67.15 percent of variance and the reliability of the questionnaire is .903, as shown in Table 2.

| Table 2 Factor Loadings of Consumer Evaluation Items | |

| Items | Factor Loadings |

| Liking | 0.869 |

| Intention to buy | 0.864 |

| Likelihood to buy | 0.852 |

| Desire | 0.836 |

| Favorable | 0.824 |

| Knowledge | 0.754 |

| Familiarity | 0.726 |

| Eigen value | 4.700 |

| % of variance | 67.15 |

| Alpha reliability | 0.903 |

The Main Study

Sample and data collection: The population for the main study is actual shoppers hailing from 13 different locations in India. The sampling technique used to choose locations was judgmental in order to ensure wider geographical spread and the presence of the retail outlets namely, Big Bazaar and Shoppers Stop. The major inclusion criteria for shoppers are the experience in shopping at Big Bazaar and Shopper Stop and awareness of the PLBs ‘fresh & pure’ and ‘stop’ belonging to these establishments. From this population many shoppers were randomly approached during their shopping visits to either Big Bazaar or Shoppers stop retail outlets. The data collection was done by field investigators appointed and trained by the author in different cities. Each field investigator had four sets of questionnaires one for each experimental condition. While the 7-items questionnaire was same for all four experimental conditions the instructions contained respective brand names as indicated in the above. The field investigator approached each potential respondent and asked few filter questions to determine the inclusion criteria. If the respondent was qualified, one of the experimental condition was randomly picked and the respondent was asked to rate the seven items. This process was continued for a week to 10 days and a total of 275 shoppers data which were complete in all respects were considered for analysis. It took less than 5 minutes for each respondent to complete the questionnaire. All respondents were cooperative. Some demographic information was also collected along with the ratings. Following is the distribution of sample for four experimental conditions: EF = 69, EP = 65, NF = 71 and NP = 70. The sample contained: 146 males (53.1%) and 129 females (46.9%); 116 respondents were less than 25 years of age (42.2%), 111 were between 6 to 35 years (40.4%) and 48 were above 36 (17.5); 48 undergraduates (17.5%), 114 graduates (41.5%) and 113 post graduates and above (41.1%); in monthly income in rupees about 100 were earning less than 20K (36.4%), 92 were earning 21 to 40 K (33.5%), 47 were earning 41 to 60 K (17.5%) and 36 were earning above 60 K (13.1%); and 65 were students (23.6%), 27 were businessmen (9.8%), 164 were from service (59.6%) and 19 were from other categories including unemployed, housewives and retired (6.9%).

Analytical strategy

A 2 x 2 Factorial ANOVA design for between subjects was used to analyze the data. Preliminary diagnostic tests on consumer evolution variables were performed to test normality and identify outlier. F test for main effect- branding strategies was used to test the hypothesis. Though product type is used as a blocking variable, its effects on consumer evaluation and its interaction with branding strategy on consumer evaluations were also tested to gain deeper insights.

Results

The hypothesis of the study was tested using 2 x 2 factorial ANOVA. for between subjects. Scores of customer evaluation is the dependent variable. This is the sum of all the seven items representing various facets of customer evaluation. Distributional property of customer evaluation scores are presented in Table 2. The skewness and kurtosis values are well within the limits and hence the distribution could be considered as normal. Outliers were checked using boxplots and found to include no outliers.

The independent variables are branding strategies which is in two categories viz., extended brand and new brand and product type which is also in two categories viz., functional and prestige products. The mean values, standard deviation and number of respondents in each of the four experimental conditions for customer evaluation scores are presented in Table 3.

| Table 3 Descriptive Statistics for Customer Evaluation Score | ||

| N | Valid | 275 |

| Missing | 0 | |

| Mean | 28.415 | |

| Median | 29.000 | |

| Mode | 33.00 | |

| Std. Deviation | 9.034 | |

| Skewness | -.181 | |

| Std. Error of Skewness | 0.147 | |

| Kurtosis | -.227 | |

| Std. Error of Kurtosis | 0.293 | |

The 2 x 2 ANOVA, presented in Table 4, shows the statistical significance of the main and interaction effects. The two main effects are statistically significant. The difference in customer evaluation means between extended and new strategies, and between functional and prestige products are statistically significant in Table 5.

| Table 4 Means and Standard Deviations for Four Experimental Conditions | ||||

| Type of product | Branding strategy | |||

| Extended Brand | New Brand | Total | ||

| Functional | Mean | 31.188 | 28.648 | 29.900 |

| Sd | 8.468 | 9.422 | 9.023 | |

| N | 69 | 71 | 140 | |

| Prestige | Mean | 27.754 | 26.057 | 26.874 |

| Sd | 9.636 | 7.963 | 8.816 | |

| N | 65 | 70 | 135 | |

| Total | Mean | 29.522 | 27.362 | 28.415 |

| Sd | 9.182 | 8.794 | 9.034 | |

| N | 134 | 141 | 275 | |

| Table 5 Anova Results for Main and Interaction Effects | |||||

| Source of variation | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Between Branding strategies | 308.237 | 1 | 308.237 | 3.902 | 0.049 |

| Between product types | 623.275 | 1 | 623.275 | 7.890 | 0.005 |

| Branding strategies x Product types | 12.224 | 1 | 12.224 | 0.155 | 0.694 |

| Error | 21408.581 | 271 | 78.998 | ||

| Total | 22352.317 | 274 | |||

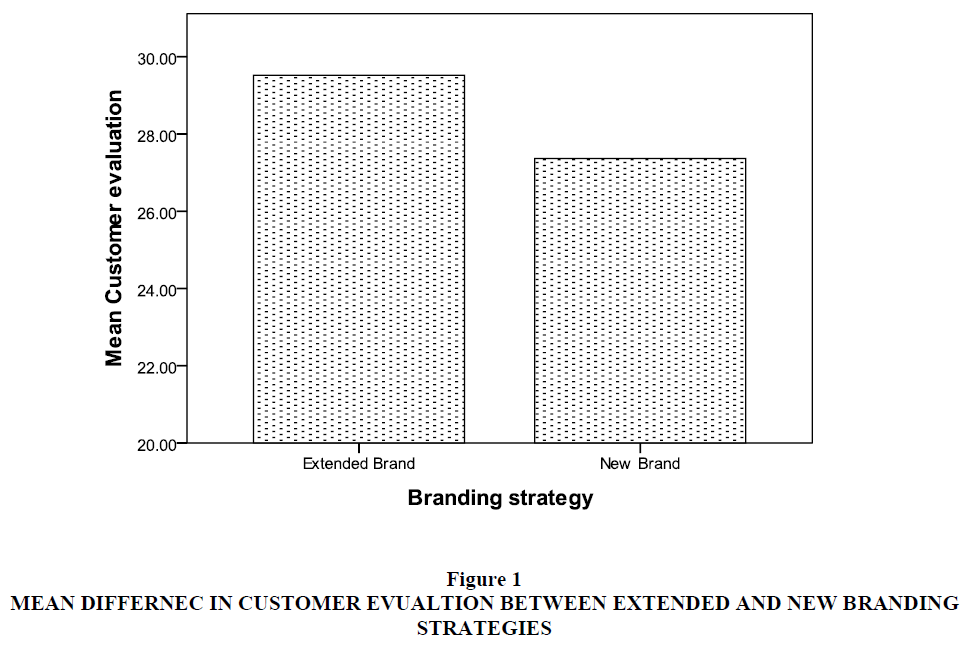

The F ratio for branding strategies is 3.902, which is significant beyond 5% level at 1 and 271 degrees of freedom. Similarly, the F ratio for product types is 7.890, which is also significant beyond 5% level at 1 and 271 degrees of freedom. F ratio for interaction of branding strategies and types of product is not statistically significant (F = 0.155; df = 1 and 271; p = 0.694). Examination of means of the two significant main effects shows that product introduced as an extended brand is favorably evaluated than products introduced as a new brand. This finding confirms the hypothesis of the study. Even though it is not postulated, the functional products are evaluated more favorably than prestige products. There is no statistically significant difference in customer evaluation of functional and prestige products within extended and new brand strategies. Figure 1 depicts the main effects of branding strategies on customer evaluation.

Discussion and Managerial Implications

Both academicians and practitioners devote considerable attention on researching branding strategies. However, there is a dearth of research on consumer evaluation of private label branding strategies. The goal of this paper is to find out the impact of branding strategies on consumer attitudes and purchase intentions for new products launched by retailers. The results of this study indicate that, in general, consumers evaluate brand extensions of private labels more favorably. Intrestingly, Mc Carthy, Heath and Milberg (2001) in their study of brands found that consumers rated brand extensions higher than products with new brand names.

One primary reason for shoppers favoring private label extension (here after PLE) could be risk reduction. Customers are more comfortable buying a familiar brand and established brands send quality cues. Parent brand’s awareness, credibility and reputation play a key role while consumers purchase a brand extension (Aaker and Keller, 1990; Dacin and Smith, 1994; Park et al 2001). A highly reputed brand acts as a rejuvenator and risk reducer and therefore creates higher product trial (Keller, 2009). A new private label (NPL) lacks these inherent advantages and has to build its credibility over a period of time.

Another possible explanation could be that the PLBs offered in the study may not need much support from innovators to gain market acceptance. Klink & Atheide (2009) state that “if the new product needs relatively less acceptance from innovators, brand extension becomes a more viable option.” And finally, as mentioned earlier, for the study PLBS with highest perceived quality were employed. In fact, actual quality of PLB tends to be higher than perceived quality (Kumar & Steenkamp, 2006). Shoppers who associate high quality with PLB would be more predisposed to try them.

The central contribution of this research is that PLE strategy appears to be more viable than NPL strategy for retailers. While launching new products, retailers must consider brand extension as a vital guiding strategy since consumers respond more favorably to it.

Limitations and Future Research

This study is limited only to two products (Fruit Juice and perfume). Additional research must be carried out in other product categories to further validate the findings. This study has also not considered the role of product feature similarity and concept consistency in consumer evaluation of brand extensions. Future research can be carried out to examine the impact of product similarity and concept consistency on consumer evaluation of PLB strategies.

References

- Aaker, D. (1990). Brand extensions: The good, the bad, and the ugly. MIT Sloan Management Review, 31(4), 47.

- Aaker, D.A. (1991). Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the value of brand name. New York, NY: The Free Press

- Aaker, D.A. & Keller, K.L. (1990). Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing, 54:27-41 (January).

- AC Nielsen, (2005). Private Label: a good alternative to other brands, offering the same quality &value. AC Nielsen Global Consumer Survey, http://sg.acnielsen.com/news/20050822.shtml.

- AC Nielsen (2010). The rise of the value conscious shopper. AC Nielsen Global Private Label Report.

- AC Nielsen (2018). The rise and rise again of private label, https://www.nielsen.com/ssa/en/insights/report.

- Alba, J.W., & Hutchison, J.W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 13: 411-454.

- Ambler, T., & Styles, C. (1997). Brand development versus new product development: toward a process model of extension decisions. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

- Ansellmsson, Johan, & Johansson, Ulf (2009). Retailer brands and the impact on innovativeness in the grocery market. Journal of Marketing Management, 25(1/2): 75-95.

- Arnould, E.J., Price, L.L. & Zinkhan, G. (2004). Consumers, (ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Ariberg, A., Arora, N., Henderson, T., & Kim, Y. (2014). Private label imitation of a National brand: Implications for consumer choice and Law. Journal of MarketngResearch,51(6),657-675.

- Balachander, S., & Ghose, S. (2003). Reciprocal spillover effects: a strategic benefit of brand extension. Journal of Marketing, 67:4-13.(January).

- Bao, Y., Bao, Y., Sheng, S. (2011). Motivating purchase of private brands: Effects of store image, product signatureness and quality variation. Journal of Business Research, 64: 220-226.

- Bhat, S & Reddy, S.K. (1998). Symbolic and functional positioning of brands. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 15(1): 32-43.

- Bellizzi, J., & Martin, W.S. (1982). The influence of national versus generic branding on taste perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 10: 385-96.

- Berman, B. & Evans J.R. (2001). Retail management: A strategic approach, (ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Dacin, P.A., & Smith, D.C. (1994). The effect of brand portfolio characteristics on consumer evaluations of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(2): 229-242.

- Dwivedi, A., & Merrilees, B. (2013). Retail brand extensions: unpacking the link between brand extension attitude and change in parent brand equity. Australasian Marketing Journal,21,75-84.

- Halstead, D. & Ward, C.B. (1995). Assessing the vulnerability of private label brands. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 4(3): 38–48.

- Herstein, R., & Gamliel, E. (2004). An investigation of private branding as a global phenomenon. Journal of Euromarketing, 13(4), 59-77.

- Herstein, R., & Gamliel, E. (2006). The role of private branding in improving service quality. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal.

- Kane, C.L. (1987). How to increase the odds for successful brand extension. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 4:199-203. (September)

- Kaur, H., & Pandit, A. (2015). Modelling consumer evaluation of brand extensions: Empirical evidence from India. Vision, 19(1), 37-48.

- Klink, R.R., Athaide, G.A (2009). Consumer innovativeness and the use of new versus extended brand names for new products. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27, 23-32.

- Kotler, P, et al. (2009). Marketing Management: A South Asian Perspective. 13th New Delhi: Prentice Hall

- KPMG India Report (2009), “Indian Retail: Time to Change Lanes”.

- Kumar, P. (2005). The impact of cobranding on customer evaluation of brand counterextensions. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 1-18.

- Kumar, N. (2007). Private label strategy: How to meet the store brand challenge. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Lambin, J.J., Chumpitaz, R., & Schuiling, I. (2007). Market-driven management: Strategic and operational marketing. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Martinez, E., & De Chernatony, L. (2004). The effect of brand extension strategies upon brand image. Journal of consumer marketing.

- Martinez, E., & Pina, J.M. (2003). The negative impact of brand extensions on parent brand image. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

- McGoldrick, P.J., & Marks, H.J. (1987). Shoppers' awareness of retail grocery prices. European Journal of Marketing.

- Mitchell, V., & Chaudhury, A. (2014). Predicting retail brand extension strategy success: A consumer based model. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 13(2), 93-111.

- Park, C.W., Milberg, S., & Lawson, R. (1991). Evaluation of brand extensions: The role of product feature similarity and brand concept consistency. Journal of consumer research, 18(2), 185-193.

- Pitta, D.A., & Katsanis, L.P. (1995). Understanding brand equity for successful brand extension. Journal of consumer marketing.

- Quelch, J.A., & Kenny, D. (1994). Extend profits, not product lines. Make Sure AllYour Products Are Profitable, 14.

- Rogers, E.M. (2010). Diffusion of innovations. Simon and Schuster.

- Roselius, T. (1971). Consumer rankings of risk reduction methods. Journal of marketing, 35(1), 56-61.

- Sampson, J. (2008). Marketing: the retail experience and value creation: branding. Journal of Marketing, 2008(Jun/Jul 2008), 30-31.

- Seltene, M., & Brunei, O. (2008). Brand Extension: The moderating role of the category to which the brand extension is found. Journal of Product and Brand Management,17(6) :393-402.

- Sethuraman, R., & Gielens, K. (2014). Determinants of store brand share. Journal of Retailing, 90(2), 141-153.

- Steenkamp, J.B.E., & Dekimpe, M.G. (1997). The increasing power of store brands: building loyalty and market share. Long range planning, 30(6), 917-930.

- Smith, D.C., & Park, C.W. (1992). The effects of brand extensions on market share and advertising efficiency. Journal of marketing research, 29(3), 296-313.

- Tauber, E.M. (1981). Brand franchise extension: new product benefits from existing brand names. Business Horizons, 24(2), 36-41.

- Tsai, S.P. (2005). Utility, cultural symbolism and emotion: A comprehensive model of brand purchase value. International journal of Research in Marketing, 22(3), 277-291.

- Walsh, G., & Mitchell, V.W. (2010). Consumers' intention to buy private label brands revisited. Journal of General Management, 35(3), 3-24.

- Park, C.W., Jaworski, B.J., & MacInnis, D.J. (1986). Strategic brand concept-image management. Journal of marketing, 50(4), 135-145.