Review Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 3

Consumer Viewpoint of Value Co-creation and Hedonic Value in the Hospitality Setting

Clement Nangpiire, SDD University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Wa

Citation Information: Nangpiire, C. (2024). Consumer viewpoint of value co-creation and hedonic value in the hospitality setting. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(3), 1-21.

Abstract

Value co-creation (VCC) and activities that elevates the customers desire to experience fun, entertainment; novelty and excitement are considered to enhance the customer’s perception in the hospitality context. Literature available does not explicitly explain the philosophy that motivates customers and help increase the level of hedonic values during co-creation activities. In this study, the customer’s perceptive in the hospitality context are explored by understanding the role value co-creation have on customer’s hedonic values. A multidimensional value structure is used to investigate the functional components of value co-creation and the hedonic value components, such as reputational, emotional and social values. Data was collected via self-administered questionnaires from 256 tourists and visitors of hospitality facilities. Data was analyzed using structural equation modelling software. The study revealed that through value co-creation, services rendered with the involvement of customers, increase customer emotions and creates pleasant experiences leading to customer satisfaction. The study also found that resource availability, service interaction and personal conditions are significantly linked to value co-creation whiles commitment proved not to be significantly connected to value co-creation per the PLS-SEM analysis

Keywords

Value Co-Creation; Hedonic Values; Customer Perspective; Hospitality Setting.

Introduction

Co-creation, as a new paradigm in the management literature, allows companies and customers to create value through interactions. Since the early 2000s, co-creation has spread swiftly through theoretical essays and empirical analyses, challenging some of the most important pillars of capitalist economies. In these economies, value is usually determined before a market exchange takes place (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2000, 2004a,b; Vargo & Lusch, 2004). From the co-creation perspective, suppliers and customers are, conversely, no longer on opposite sides, but interact with each other for the development of new business opportunities (Galvagno & Dalli, 2014). During recent years it has been conclusively shown that consumers and service providers across diverse domains benefit from value co-creation (Vargo et al. 2017). Arguably, value co-creation holds the most potential for complex services, such as delivery of hospitality services. Since Vargo and Lusch’s (2004) seminal article that first introduced the premises of the service logic, many articles have mentioned co-creation in their title, yet this literature is marred by significant conceptual confusion and ambiguity. Value co-creation is mostly aided by hedonic value. Hedonic value is analyzed based on the value derived from the experience, considered as a connection with the experience that produces rewarding and interesting experiences and leads to positive emotional responses (Miao, et al. 2014). Hedonism and its impact on customers have become an important object of various scientific researches in recent years in marketing literature. It should be noted that current level of theoretical and empirical researches on the phenomenon of hedonism in the theory of consumer behavior notes that hedonism as the expression of value has not been sufficiently analyze (Miao, et al., 2014). Price and quality of services are crucial characteristics for hotels to develop a competitive strategy and differentiate, since services in the hotel industry are quite homogeneous. The hospitality service literature in the consumer context is in its first stages (Chathoth, Ungson, Harrington & Chan, 2016). There is ongoing research focused on the results of hospitality and tourism value co-creation (Morosan, 2015; Solakis, Pena-Vinces, Lopez-Bonilla & Aguado, 2021). However, there is little empirical evidence that relates consumer VCC to hedonic values in the hospitality/hotel industry (Dedeoglu, Balıkcıoglu & Kucukergin, 2016; Prebensen & Xie, 2017; Morosan, 2015). Therefore, this study seeks to fill this literature gap by bringing onboard hedonic values in the hospitality industry in the co-creation sphere thus, answering the research question ‘does value co-creation and hedonic values affect customer satisfaction of the services offered by a hotel?

Value Co-Creation

According to Vargo and Sindhav (2014), value co-creation entails modifying the provider's method of interacting with all players, including employees, customers, and other stakeholders with a vested interest in the service. In their view, this requires the firm to set up new methods of engagement for the individual customers concerned. Thus, the idea of VCC is meant to bring together all the creative (innovative) energies of actors and transform the individual/collective experience and the economic resources of actors into a valuable service offering (Ramaswamy & Gouillart, 2010). Ramaswamy and Gouillart (2010), posited that consumers do collaborate with the firms in order to inspire themselves and exert some influence on the company and gain recognition. This in their view is to allow users to add their voices and become influencers which will be part of the global conversations. Customers in the hospitality industry who engage in value co-creation are seen as co-creators of value rather than passive recipients of it (Lusch & Vargo, 2006). This is because they contribute their own time, energy, money, skills, knowledge, and experiences to the service development processes. According to Zhang, et al. (2018), co-creation takes place when customers feel valued and receive reciprocity from the firm through positively engaging activities that leave them feeling happy.

They added that co-creation also happens when feedback is solicited from customers and when they interact with helpful, empathetic staff, polite and responsive personnel.

Value Co-creation as a New Paradigm

Value co-creation as an emerging paradigm proposes a change from a firm-centric view to a demand-centric and interactive process that engages resource-integrating participants for a mutually beneficial collaboration (Frow & Payne, 2011). The value co-creation paradigm seeks reciprocal value propositions amongst its stakeholders (Ballantyne & Varey, 2006), where actors can create value in collaboration with or influenced by others (Jaakola, et al. 2015). The paradigm typifies shifting boundaries, where consumers perform the simultaneous roles of providing firms with value in the form of their co-creation activity and in the form of their purchase activity (O’Hern & Rindfleisch, 2010). Customers are vital for every business, and the ability to consistently offer value to them can determine the profitability and survival of the business. Value co-creation advocates that the responsibility of value creation is transferred from inside the organization to collaborative relationships outside the physical boundaries of the organization (Frow, et al. 2015). According to Matthing, et al. (2004), continuous involvement and communication with customers will enable an organization to learn from customers and position its offering within the scope of customers’ perceived value. The process of value co-creation involves a combination of knowledge enhancement and exchange, skill acquisition, and organizational learning which can ascribe a sense of ownership to customers as a result of their contribution to the value development process (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2000). Moreover, the unique experience that is determined by the quality of interaction can serve as a potential source of competitive advantage to the organization, because customers will be likely to build emotional attachments with product offerings when they were part of its product development process.

Value co-creation attributes to the consumer a more proactive role in product development while it offers the service provider a better understanding of the customers’ needs and definition of value. Thus, the co-creation experience becomes the basis of value (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004b) and serves as a novel frontier of strategy innovation, where the interaction between the service provider and customer is a locus for value creation and extraction (Spena, et al. 2012). The service provider should initiate the process of value co-creation with an aim to engage customers in a purposeful dialogue and to reconfigure its resources and functions such that they are positioned within the customer’s creation space (Ramaswamy & Gouillart, 2010). Payne, et al. (2008) recognize the implications for service providers in their process-based co-creation framework. The supplier process should begin with a thorough understanding of customers’ value creation procedure (Solakis, et al. 2022). The supplier process combines techniques such as opportunity review; planning, testing and prototyping ideas with customers; process re-alignment; implementing solutions; developing appropriate assessment metrics; and adequately managing customer encounters. Recognizing customer processes within the supplier process will provide suppliers with a better understanding of where their offering can fit within the space of the customers’ value-creation activities, as well as clarification on how to position its internal resources/capabilities for optimal utility within the value creation process (Payne et al.,2008). The proliferation of technological innovations has been a major driver for actualizing these interactive moments. Through technological platforms, customers can be engaged in the co-creation process to generate experiences with economic, functional, and cultural benefits (Cova & Dalli, 2009).

Customer Satisfaction

It can be seen that today a lot of researchers are discussing the topic of total satisfaction. Proposers of above mentioned tend to accentuate the significance of corresponding to specifications, satisfying requirements, providing consumers with the desirable quality of services (Anwar & Abd Zebari, 2015). The thing which is seriously count nowadays is a customer satisfaction. If a client is dissatisfied, he will not come back and will not purchase your service for the second time. All the things which the company does in order to increase service quality can be counted as a zero if the customer left the hotel without being satisfied. Nowadays like never before, fulfilling consumers’ requests remains the greatest challenge (Anwar & Surarchith, 2015). In the hospitality industry, the consumer is not only the part of the actual consumption process, but moreover often has preset service and quality perspectives. Today’s hospitality industry customer is increasing time poor, more sophisticated and more demanding (Anwar, 2017). Before applying management strategies for service quality improvement, it is essential to comprehend where the clients are originating from and what satisfaction level they are expecting. According to Anwar, (2016) “satisfaction is a person’s feeling of pleasure or disappointment resulting from comparing a product’s perceived performance or outcome in relation to his or her expectation”. In the other words, if service quality matches consumer’s expectation, the customer will be satisfied. Nevertheless, in the hospitality industry to meet customer’s expectations is hard enough Kotler & Armstrong (2001).

Customer satisfaction is a critical component of the hospitality industry, as it can impact customer loyalty, word-of-mouth recommendations, and profitability. Studies have shown that factors such as service quality, cleanliness, and price can influence customer satisfaction in the hospitality industry (Kim & Lee, 2018). Hedonic values and customer satisfaction are related because hedonic values can influence customer satisfaction. If a service provides positive hedonic values, such as enjoyment or excitement, it can lead to higher levels of customer satisfaction. On the other hand, if a service fails to provide positive hedonic values or even provides negative hedonic values, such as frustration or boredom, it can result in lower levels of customer satisfaction. Therefore, companies often try to incorporate hedonic values into their services to increase customer satisfaction. They do this by designing services that are not only functional but also enjoyable to use.

Empirical Literature and Hypothesis Development

Resource Availability and value co-creation

The experiences that tourist or visitors receive from different service points in the hotel differ from each other based on the availability of required resources. “Resource availability” implies that organizations require spare resources for flexible usage for anticipatory capabilities (Duchek, 2020). A company’s financial position is a source of strength and assurance. Other resources include “social resources,” such as shared goals, mutual respect and a trusting organizational culture, which are necessary for coping capabilities. Meanwhile, “power and responsibility” involves decentralization, self-organization, shared decision making, organic structures, and employee involvement and empowerment, which are largely related to adaptation capabilities (Duchek, 2020).

In the context of hospitality, resources refer to the tangible and intangible assets that a hotel or other hospitality establishment uses to produce and deliver its services. These resources can include physical assets such as buildings, furniture, equipment, and supplies, as well as intangible assets such as employees, brand reputation, and customer relationships. Effective management of these resources is critical to the success of a hospitality business, as it directly affects the quality of service provided to customers. For example, if a hotel has inadequate staffing levels, it may struggle to provide prompt and efficient service to guests, leading to negative reviews and a decline in customer satisfaction (Chen & Li, 2012). Physical resources, such as buildings and equipment, can also impact the quality of service provided. For example, outdated or poorly maintained equipment may result in slower service or subpar food and beverage offerings (Wang & Lu, 2016).

In addition to managing existing resources effectively, it is also important for hospitality businesses to continuously invest in and update their resources. This can help to maintain a competitive advantage, enhance customer experiences, and drive growth and profitability (Druker & Simons, 2013). In conclusion, resource availability plays a crucial role in the hospitality industry. Proper allocation and utilization of both tangible and intangible resources can help to deliver high-quality services to customers, co-create value, improve brand reputation, and drive business growth. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H1 Resource availability will have a positive impact on value co-creation.

Commitment and Value co-creation

Organizational commitment can be the degree in which an individual adopts organizational values in identifying problems to fulfill his job responsibilities (Mohammed & Eleswd, 2013). According to Azeem (2010), Stinglhamber, et al. (2015), strong desires in organizational goals and values, willingness to do a lot of effort on behalf of the organization and strong desire to remain a member of the organization is employees’ ability in analyzing the performance of various cultures.

The term “commitment” has been defined as an individual’s pride in belonging, their concern for long-term success, and a desire as a customer to contribute toward the betterment of an organization (Morgan and Hunt, 1994).

From the customer's perspective, commitment in value co-creation can involve actively participating in the co-creation process by providing feedback, sharing information, and taking on a co-creative role. This may require a willingness to experiment, to try new ideas, and to accept some level of risk.

On the other hand, service providers must also commit to the value co-creation process by being open and responsive to customer feedback, actively engaging with customers, and being willing to adapt their products or services to meet changing customer needs. This may require a shift in organizational culture, as well as a willingness to invest time, resources, and effort in building relationships with customers.

In summary, commitment by both customers and service providers is crucial to successful value co-creation. Customers must be willing to actively participate and share their ideas and feedback, while service providers must be open and responsive to customer needs and willing to adapt their products or services accordingly. When both parties are committed to the co-creation process, they can create value that is more meaningful and relevant to the customer, leading to increased customer satisfaction and loyalty.

In the context of value co-creation, commitment can be defined as the extent to which individuals or organizations are willing to invest resources, effort, and time to collaborate with each other to create value that is beneficial for all parties involved. Commitment involves a willingness to work towards a shared goal, to overcome obstacles and challenges, and to continue to invest in the collaborative process.

According to Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004), value co-creation occurs when companies and their customers work together to create value through mutual interactions and exchanges. In this context, commitment is crucial for the success of value co-creation because it requires individuals and organizations to collaborate and work together towards a common goal, often involving a significant investment of resources and effort.

Several studies have identified different types of commitment in the context of value co-creation. For example, Bove, L. L. (2016) identified three types of commitment in the context of service co-creation: affective commitment (based on emotional attachment and loyalty to the collaboration), normative commitment (based on a sense of obligation and responsibility to the collaboration), and continuance commitment (based on the perceived cost of leaving the collaboration).

Overall, commitment is an important component of successful value co-creation, as it promotes collaboration, trust, and investment in the process. Without commitment, individuals and organizations may be less willing to work together and invest resources in the collaborative process, which could ultimately hinder the creation of value for all parties involved. All these discussions lead to propose the following hypothesis.

H2 Commitment will have a positive impact on value co-creation.

Service Interaction and Value co-creation

According to Vargo and Lusch (2008), service interaction is the "foundation of value co-creation," and it involves the integration of the customer's resources, skills, and knowledge with the service provider's resources, skills, and knowledge to create value. Service interaction can take various forms, including direct and indirect contact between the service provider and the customer.

According to Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004), service interactions can be divided into three categories: customer-to-customer interactions, customer-to-employee interactions, and employee-to-employee interactions. Each of these interactions can contribute to value co-creation in different ways. For example, customer-to-customer interactions can enhance the social value of a service, while employee-to-employee interactions can improve the quality of service delivery.

Direct service interaction involves face-to-face or virtual communication between the service provider and the customer. This type of interaction allows for the exchange of information, ideas, and feedback, which can help the service provider understand the customer's needs and preferences better. Indirect service interaction, on the other hand, involves interactions between the customer and other stakeholders in the service ecosystem, such as other customers, suppliers, or regulators. Indirect interaction can also contribute to value co-creation by providing feedback and ideas for improving the service.

Studies have shown that effective service interaction is critical for value co-creation. For example, in a study by Kabadayi and Price (2014), they found that effective communication and collaboration between service providers and customers increased the likelihood of co-creating value. Similarly, in a study by Frow, Nenonen, Payne, & Storbacka, (2015). they found that service interaction was a critical factor in the co-creation of value in a business context.

Service interaction plays a critical role in value co-creation by facilitating collaboration and the exchange of resources, knowledge, and skills between service providers and customers. By working together, service providers and customers can create more value than they could individually; resulting in more satisfied customers and improved business outcomes.

Ostrom, Elinor (2010) argues that service interactions are important for developing a relationship between the provider and the customer. This relationship can lead to increased trust, loyalty, and satisfaction, which are all important factors in creating value for the customer. In terms of the above discussions, the following hypothesis is developed.

H3 Service interactions will have a positive impact on value co-creation

Personal Condition and Value co-creation

Grönroos and Ravald (2011) suggest that customers' personal values, beliefs, and attitudes towards co-creation activities can significantly impact their participation and contributions. Similarly, Vargo and Lusch (2016) argue that customers' knowledge, skills, and resources are essential personal conditions that can facilitate or hinder their involvement in value co-creation.

Other researchers have identified additional personal conditions that are relevant to value co-creation. For instance, Pera, Vidal-Salazar, & Aldás-Manzano, (2015) suggest that customers' motivation, trust, and commitment to the co-creation process are crucial factors that influence their willingness to participate. In addition, Karpen, Ratzlaff, & Hesse, (2018) highlight the role of customer personality traits, such as openness to experience, in shaping their engagement in co-creation activities. Lusch and Nambisan (2015) identified customer motivation as a critical personal condition that affects value co-creation. They argued that customers who are highly motivated to participate in value co-creation are more likely to contribute their time, resources, and knowledge to the process. Personal conditions of customers are an important determinant of their participation and contributions in value co-creation. Firms should take these conditions into account when designing and implementing co-creation initiatives to ensure that they are tailored to the needs and preferences of their customers.

Moreover, research has shown that the personal conditions of customers can vary depending on the type of co-creation activity. For instance, a study by Ranjan and Read (2016) found that customers who were more willing to participate in idea generation activities had different personal conditions than those who were more interested in designing or testing new products or services. With all these inputs, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H4 Personal conditions will have a positive impact on value co-creation

Value Co-creation and Hedonic Value

Owing to the predominant service context of the hospitality industry, customers’ hedonic values are satisfied mainly from experiences and interactions. Value creation may thus be contingent on the ability to co-create these customer experiences, such that customers can be active participants in building their own experiences from personalized and interactive moments with the service provider (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004a). The utility of information and communication technology (ICT) in Value co-creation for hospitality services has become apparent in tech-enabled platforms such as online social communities, online booking, virtual tourism experiences, advertising, specialized mobile apps, etc. The online community offers the benefits of social inclusion and information sharing through information dissemination, user-generated comment, interaction, and mutual assistance from hotel and fellow community members. Online communities also help to establish valuable relationships between old and new customers (Gebauer, et al. 2010). Ayeh, et al. (2013) view user-generated comment as a powerful tool for influencing consumer buying behaviour because it is less partisan and has a positive effect on potential customers’ likelihood to use information from these comments for their travel planning and hotel reservations. The growing access to smartphones has also driven the utility of mobile commerce in the hospitality services context. Hotels are designing device-enabled applications to interact with their customers and design services according to personalized needs and preferences. These hotel-designed apps enable customers to actively engage and determine the services received, such as room features, concierge services, taxi services, and check in Sarmah, Kamboj and Rahman, (2017). Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H5 value co-creation will have a positive impact on hedonic values

Hedonic Values and Customer Satisfaction

Hedonic value, on the other hand, refers to the pleasure or enjoyment that a customer derives from a product or service. It can also be used in economic theories to describe the value that individuals place on different goods or services based on the pleasure or satisfaction that they provide. In the hospitality context, hedonic value can be created through things like this can include the enjoyment of a comfortable room, delicious food, or a relaxing spa experience (International Journal of Business Environment).

One prominent approach to studying hedonic values is the "three-factor theory" proposed by Russell and Pratt (1980). According to this theory, the experience of pleasure or enjoyment is determined by three factors: the degree of arousal (e.g., excitement), the degree of pleasure-displeasure (e.g., happiness vs. sadness), and the degree of dominance (e.g., feeling in control vs. feeling powerless).

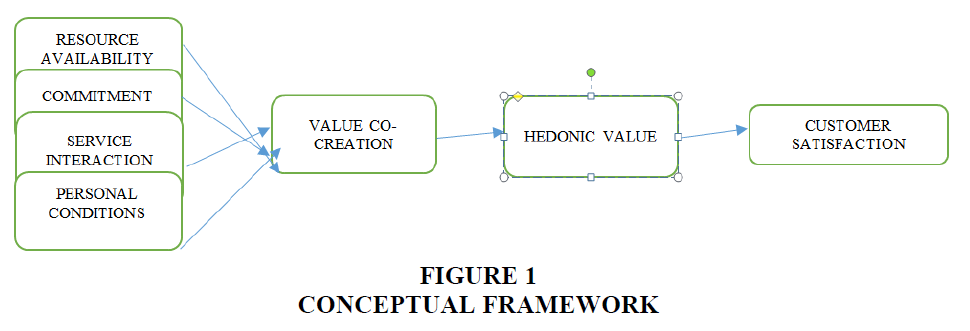

Another popular approach to studying hedonic values is the "flow" theory proposed by Csikszentmihalyi (1990). According to this theory, people experience the most pleasure and enjoyment when they are engaged in activities that challenge their skills and abilities, while also providing them with a sense of control and focus. From a customer perspective, the goal of value co-creation and hedonic value is to create a personalized and enjoyable experience that meets their specific needs and preferences. This can lead to increased satisfaction, loyalty, and positive word-of-mouth recommendations. Therefore, we put forward the following relationship Figure 1.

H6 Hedonic values will have a positive impact on customer satisfaction.

Proposed Conceptual Framework

Research Methodology

Research Design

The author of the study used primary data extracted from the results of the questionnaire and survey because primary data has not undergone any human intervention, making its validity higher, improved interpretation, attention to relevant research questions, and decency of the data. The variables selected were suitable for data availability for all the stakeholders involved in the hospitality industry. The author utilized SMART-PLS 4 for the data analysis since the application provides statistical values of the model. The author employed PLS-SEM because of the study's purpose to investigate the interaction between independent and dependent components using effect magnitude and predictive relevance.

Population and Sampling

The author targeted all males and female’s guests or customers of the hospitality industry in Ghana who are above 18 years. The focus was on customers who patronized hospitality facilities in Ghana and was not limited to any hotel tagged with a specific star rating.

The sample size for the study is two hundred and fifty-six (256) credible guests of hospitality/hotel facilities in Ghana. It was critical to select a sampling method that would make it easy to collect data after identifying the minimum sample size required for this inquiry. The non-systematic technique employed in this study was convenience sampling.

Data

In obtaining data for this study, a questionnaire, survey, and participant setting were developed to uncover the participants' real perceptions and experiences in the hospitality industry. The study's hypotheses informed the design of the questionnaires used to collect data. It was carried out to ensure the goal of the study was ultimately met. Google Forms and in-person administrations of questionnaires were both used for administration. The survey could only be completed once by each respondent.

After the questionnaire was designed it was administered through online platforms where 256 respondents answered correctly and 3 respondents did not answer correctly. We removed the three responses that were not correctly answered.

After the questionnaire was created, an instrument pre-test was conducted before a pilot test. By seeking the opinions of experts on the test items, the questionnaire was pilot-tested ahead of time. They offered helpful criticism, which assisted in enhancing the questionnaire's substance. This procedure was carried out to ensure the legitimacy of the content. A pilot test was carried out after the questionnaire was modified in response to expert feedback.

Data Processing

Data cleaning was done to prepare the data for the analysis of statistics. To verify our hypotheses, we employed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and determine the significance of the predictor variable. SEM is appropriate for this study because it is adaptable to both measurable (observed) and unmeasurable (latent) factors, whereas, in the past, only measurable variables were used in evaluations. The partial least squares (PLS) focuses on variance analysis and can be performed with software such as Smart-PLS and ADANCO. PLS-SEM is useful in studies with more respondents and uneven data distribution. Data were coded and organized into integrated constructs in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) before being fed into the Smart-PLS tool for analysis. The data were subjected to inferential as well as descriptive analysis.

Findings Analysis and Discussion

Demographic Characteristics of Respondent

Assessment of Measurement Model

Empirical estimates of the associations between the indicators and the constructs (measurement models) and between the constructs (structural model) are provided via model estimation (Hair Jr et al., 2021). In PLS-SEM, analyzing the measurement models is the starting point for assessing the outcomes. Relationships between each latent variable structure and its corresponding indicator variables are represented by the outer models (also called measurement models).

In essence, the evaluation or assessment of measurement model aids the researcher in comparing the theory chosen for the study with the data gathered for the investigation. The appropriate standards for evaluating the measurement model vary depending on whether they are reflective or formative constructs (Henseler, 2018). Because all the constructs in this study were reflective there is the need to test measurement model’s reliability and validity before you carried out the test for structural model. This study assessed the measurement model using indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

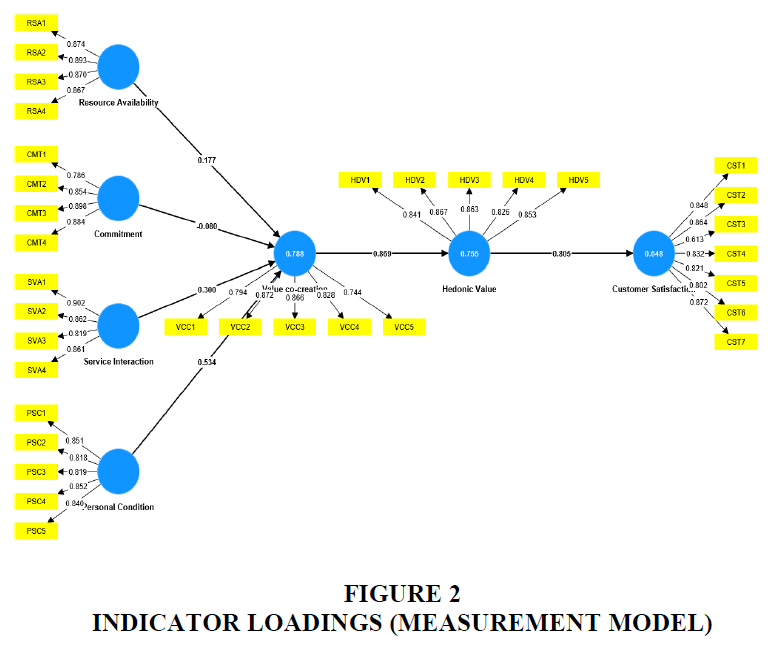

Indicator Reliability

The first step in assessing a reflective measurement model is to look at the indicator loadings. Loadings above 0.708 are preferred since they show that construct is sufficiently reliable to account for almost 50% of the variation in the indicator (Hair et al., 2019). In this case, all indicators are strongly weighted on their underlying latent factors. Therefore, none were taken out of the model (Straub et al., 2022). That is to say, all indications were above the needed threshold when the initial study was performed. The model was run using the PLS algorithm, the indicator loadings are displayed in Figure 2.

Internal Consistency Reliability

Cronbach's alpha, Joreskog's composite reliability, and Rho A were employed to assess the internal consistency reliability of the survey. The results are presented in Tables 1 & 2.

| Table 1 The Demographic Characteristics of Respondents | |||

| Demographics | Characteristics | Number | Percentage |

| Gender | Male Female |

146 110 |

57% 43% |

| Age | 18 – 24 years 25 – 34 years 35 – 44 years 45 – 54 years 55 years and above |

86 94 46 22 8 |

33.6% 36.7% 18% 8.6% 3.1% |

| Portfolio | Occupation Employed (Full time) Employed (part time) Self-employed Unemployment Others (specify) |

86 62 39 47 18 4 |

33.6% 24.2% 15.2% 18.4% 7.2% 1.4% |

| Educational Qualification | High school Diploma Degree Masters Doctorate/Higher |

35 43 139 28 11 |

13.7% 16.8% 54.3% 10.9% 4.3% |

| How often do you stay in hostels or other type accommodation per year | Less than 1 time 1 – 2 times 3 – 5 times More than 5 times |

82 85 52 37 |

32% 33.2% 20.3% 14.5% |

| Table 2 Results of Internal Consistency Reliability | |||

| Constructs | Cronbach's alpha | Composite reliability (rho_a) | Composite reliability (rho_c) |

| Commitment | 0.878 | 0.881 | 0.917 |

| Customer Satisfaction | 0.912 | 0.922 | 0.930 |

| Hedonic Value | 0.904 | 0.905 | 0.929 |

| Personal Condition | 0.892 | 0.893 | 0.921 |

| Resource Availability | 0.899 | 0.899 | 0.930 |

| Service Interaction | 0.884 | 0.887 | 0.920 |

| Value co-creation | 0.879 | 0.883 | 0.912 |

Table 2 displays that the Cronbach alpha for all latent variables and constructs was more than 0.70. Cronbach alpha values which range from 0.763 to 0.903 signifies that the model is having good internal consistency. Composite reliability, in contrast to Cronbach's alpha, is stronger because the items are weighted according to their separate loadings on the construct indicators. Based on the results, the composite reliability values (rho_c) vary from 0.862 to 0. 0.933, which is good (see Table 2). In general, more trustworthy results have greater value. For instance, "acceptable in exploratory research" would be a dependability score of 0.60–0.70, while "satisfying to good" would be a value of 0.70–0.90. A value of 0.95 or higher is problematic since it implies that the constituents are not necessary, which reduces construct validity (Mikulić). From Table 2, none of the composite reliability was 0.862 or more. Lastly, rho_A is a more precise option to Cronbach's alpha and the composite reliability, which is typically found to lay between the two. Maintaining a Rho_ A around 0.70 is advised. As can be shown in Table 2, the Rho_ A values of all constructs are higher than 0.70. A higher Rho_A means the data is verified and reliable.

Convergent Validity

Convergent validity measures how well a construct accounts for differences in its constituent parts. Concerning convergent validity, it is the rate at which all indicators in the model relate to other items of the same latent variable. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) measures convergent validity. By calculating AVE from each component, outer loadings allow for the evaluation of convergent validity. The results of the convergent validity are presented in Table 3.

| Table 3 Result of Convergent Validity | |

| Constructs | Average variance extracted (AVE) |

| Commitment | 0.734 |

| Customer Satisfaction | 0.659 |

| Hedonic Value | 0.723 |

| Personal Condition | 0.699 |

| Resource Availability | 0.768 |

| Service Interaction | 0.742 |

| Value co-creation | 0.676 |

By calculating AVE from each component, outer loadings are applicable for evaluating convergent validity. From Table 3, all latent variables showed high loading which is greater than 0.50. Thus, convergent validity was met because all AVE values in Table 3 were greater than 0.50.

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity requires that each construct represents a phenomenon that is not captured using any other component of the model (Hair Jr et al., 2020). To assess discriminant validity, the study employed Fornell-Larcker (1981) criterion. The results of the cross-loadings are presented in Table 4.

| Table 4 Results of Fornell-Larcker (1981) Criterion | |||||||

| Constructs | Commitment | Customer Satisfaction | Hedonic Value | Personal Condition | Resource Availability | Service Interaction | Value co-creation |

| Commitment | 0.857 | ||||||

| Customer Satisfaction | 0.812 | 0.852 | |||||

| Hedonic Value | 0.787 | 0.805 | 0.850 | ||||

| Personal Condition | 0.800 | 0.836 | 0.865 | 0.869 | |||

| Resource Availability | 0.719 | 0.789 | 0.809 | 0.852 | 0.876 | ||

| Service Interaction | 0.778 | 0.788 | 0.803 | 0.862 | 0.862 | 0.864 | |

| Value co-creation | 0.778 | 0.795 | 0.813 | 0.822 | 0.833 | 0.868 | 0.869 |

Discriminant validity is frequently assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion by contrasting the AVE (shared variance within) of the constructs with the squared correlation between them (shared variance between). Latent variables tend to correspond more closely to their corresponding indicators than to any other latent variables, as shown in Table 4. Figures reflecting this are presented in bold in the Table 4. The highest values across rows and columns are highlighted in bold. Discriminant validity has been established here.

Structural Model Assessment

The structural connection between components is modeled in the inner model. The structural model is utilized to test the direct effect and connection between the dependent and independent variables. The structural evaluation criteria include multicollinearity issue, path coefficient, coefficient of determination (R2), and Goodness of Fit (GOF).

Evaluating Multicollinearity Issue of Structural Model

To ensure that collinearity does not skew the results of the regression, it is important to test for it before the structural relationships can be evaluated. The degree of multicollinearity was evaluated by looking at the VIF values across all of the different measures. Collinearity problems can be avoided with a cut-off of 5 or fewer (Joe F Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2011). When VIF is greater than 5, there is likely collinearity among the predictor constructs. According to Table 5, there are no collinearity issues because all VIF values are less than 5. Table 4 presents the findings from the VIF test.

| Table 5 Results of Collinearity Statistics | |||||||

| Constructs | Commitment | Customer Satisfaction | Hedonic Value | Personal Condition | Resource Availability | Service Interaction | Value co-creation |

| Commitment | 1.351 | ||||||

| Customer Satisfaction | |||||||

| Hedonic Value | 1.000 | ||||||

| Personal Condition | 1.396 | ||||||

| Resource Availability | 3.965 | ||||||

| Service Interaction | 2.966 | ||||||

| Value co-creation | 1.000 | ||||||

Evaluating Path Coefficients Significance in Structural Model

The path coefficient between the model's latent variables needs to be evaluated for significance once collinearity has been checked. The path coefficient was used to determine if there is a correlation between the dependent, mediating, and independent variables. It was done through the process of bootstrapping with 5000 samples on Smart-PLS 4. The findings are presented in Table 6.

| Table 6 Direct Relationship Direct Relationship of Hypothesis Testing | |||||||

| Relationship | Path coefficient | T values | P values | 95% CI LL | 95% CI UL | Decision | |

| H1 | Resource Availability -> Value co-creation | 0.177 | 1.940 | 0.052 | 0.028 | 0.328 | Significant |

| H2 | Commitment -> Value co-creation | -0.079 | 0.616 | 0.538 | -0.300 | 0.117 | Insignificant |

| H3 | Service Interaction -> Value co-creation | 0.300 | 2.784 | 0.005 | 0.118 | 0.474 | Significant |

| H4 | Personal Condition -> Value co-creation | 0.533 | 4.971 | 0.000 | 0.348 | 0.699 | Significant |

| H5 | Value co-creation -> Hedonic Value | 0.870 | 39.945 | 0.000 | 0.829 | 0.900 | Significant |

| H6 | Hedonic Value -> Customer Satisfaction | 0.805 | 25.137 | 0.000 | 0.743 | 0.850 | Significant |

T-statistics was used to analyze the direct and indirect effects of the latent variables. Table 5 shows five out of six hypotheses tested have crucial t-values of 1.65 or above, indicating that they are supported. Thus, H1, H3, H4, H5 and H6 were significant and H2 is not significant.

Goodness of Fit (GOF)

Goodness of Fit (GOF) shows how well or poorly the model is matched. Additionally, misspecifications in the measurement and structural models can be discovered with the help of the GOF test. The most common measure of GOF is the R square (R2) determination of coefficient and Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR).

A model's ability to explain data is quantified by its R2 value, which is equal to the fraction of the total variance that can be attributed to each of the model's internal constructs. The results of the GOF are shown in Tables 6-9.

| Table 7 Results of R Square | ||

| Constructs | R-square | R-square adjusted |

| Customer Satisfaction | 0.648 | 0.646 |

| Hedonic Value | 0.755 | 0.754 |

| Value co-creation | 0.788 | 0.785 |

| Table 8 Result of SRMR | ||

| Saturated model | Estimated model | |

| SRMR | 0.048 | 0.096 |

| Table 9 Results of F Square | |||||||

| Constructs | Commitment | Customer Satisfaction | Hedonic Value | Personal Condition | Resource Availability | Service Interaction | Value co-creation |

| Commitment | 0.005 | ||||||

| Customer Satisfaction | |||||||

| Hedonic Value | 1.838 | ||||||

| Personal Condition | 0.250 | ||||||

| Resource Availability | 0.038 | ||||||

| Service Interaction | 0.086 | ||||||

| Value co-creation | 3.088 | ||||||

The coefficient of determination (R2) of the endogenous construct was assessed. R2 measures the variance, which is described in each of the endogenous constructs and thus, is a measure of the models explanatory power (Shmueli and Koppius, 2011). R2 ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values showing greater explanatory power (Hair et al, 2016).

SRMR was utilized in the investigation. This is because numerous researches has found SRMR to be a reliable method to analyze the goodness of fit in PLS-SEM. The lower the SRMR, the better the fit of the model. When the SRMR is 0, the fit is ideal. A SRMR of 0.08 or less, however, is considered to be optimal. Table 7 shows the calculated SRMR value is less than 0.08, and thus, indicates the fit of the model.

Evaluating the Effect Size

Assessing the effect size of each path in the SEM using Cohen's f2 is the next step after analyzing the GOF of the structural model (Goulet-Pelletier and Cousineau, 2018). To determine whether or not an independent construct significantly influences the dependent construct, researchers use effect sizes (Goulet-Pelletier and Cousineau, 2018). Meaning, it assesses how much weight the dependent construct has in the context of the independent construct (Gignac and Szodorai, 2016).

If the f2 value is below 0.020, the independent construct has a small effect on the dependent construct, and if it is between 0.150 and 0.350, the independent construct has a moderate effect on the dependent construct (Gefen et al., 2011).

Hypotheses

From the analysis in Table 5 showing the direct relationship for hypothesis testing, the following findings were revealed. Hypotheses tested having t-values of 1.65 or above, indicates that they are significant or supported.

First, the results in Table 5 revealed a t-value of 1.940 and the accompanying p-value of 0.052 indicated that Resource availability and value co-creation had a coefficient value of 0.177. These results show that Resource availability and value co-creation is significant and has direct relationship with value co-creation, hedonic values and customer satisfaction. This indicates that resource availability plays a crucial role in the hospitality industry. Proper allocation and utilization of both tangible and intangible resources can help to deliver high-quality services to customers, co-create value, improve brand reputation, and drive business growth. This result supports the H1 hypothesis.

Table 5 reveals that the value of the commitment coefficient is -0.079, with a matching t-value of 0.616 and a p-value of 0.538, which is not significant and has no direct relationship with value co-creation, hedonic values and customer satisfaction. This means that without commitment, individuals and organizations may be less willing to work together and invest resources in the collaborative process, which could ultimately hinder the creation of value for all parties involved. This means the decision makers must ensure necessary commitment from workers of hospitality facilities to ensure value co-creation and customer satisfaction. Indicators. Therefore, this result does not support the H2 hypothesis.

Table 5 results reveal that service interaction and value co-creation coefficient is 0.300 and that the t-value is 2.784, with a matching p-value of 0.005, which significantly have a direct relationship with value co-creation, hedonic values and customer satisfaction. This means that service interaction plays a critical role in value co-creation by facilitating collaboration and the exchange of resources, knowledge, and skills between service providers and customers. By working together, service providers and customers can create more value than they could individually, resulting in more satisfied customers and improved business outcomes. Hence, this result supports the H3 hypothesis.

The personal condition coefficient value was discovered to be 0.533, with a matching t-value of 4.971 and a corresponding p-value of 0.000 which tends to be significantly influential. This means that there is a causal connection or even a meaningful one between value co-creation, hedonic values and customer satisfaction. This is a reflection that customers' personal values, beliefs, and attitudes towards co-creation activities can significantly impact their participation and contributions co-creating value. This brings us to the conclusion that the H5 hypothesis should be accepted.

In addition, value co-creation and hedonic value have a coefficient value of 0.870, with a matching t-value of 39.945 and a significance level of 0.000 which is the p value. This proves that there is a significant effect of value co-creation on hedonic values. For value co-creation to take place people must participate and this participation must be enjoyable in the service creation process which will then bring about hedonism which refer to the pleasure or enjoyment that a customer derives from a product or service such as hospitality services. This also brings us to the conclusion that the H5 hypothesis should be accepted.

The final hypothesis H6 concludes that hedonic values have a significant influence on customer satisfaction with a coefficient value of 0.805 and a t-value and p-value of 25.137 and 0.000 respectively. providing them with a sense of control and focus. From a customer perspective, the goal of value co-creation and hedonic value is to create a personalized and enjoyable experience that meets their specific needs and preferences. This can lead to increased customer satisfaction creating the conclusion that H6 hypothesis should be accepted.

Discussion of Results

According to the study, proper allocation and utilization of both tangible and intangible resources can help to deliver high-quality services to customers, co-create value, improve brand reputation, and drive business growth. It mainly depends physical resource availability which customers get access to co-create value as well as enjoyment and pleasure which defines hedonic values and also the data analysis supports the hypothesis that resource availability is positively associated with value co-creation.

However, commitment by both customers and service providers is crucial to successful value co-creation. Customers must be willing to actively participate and share their ideas and feedback, while service providers must be open and responsive to customer needs and willing to adapt their products or services accordingly. Commitment from both parties is crucial in the hospitality industry for a successful co-creation of value and satisfaction but the outcome of the analysis reveals hypothesis of commitment being negatively connected to value co-creation, making the outcome insignificant. This shows that most service providers in these hospitality facilities lack commitment one way or the other. Commitment goes both ways, so when one party is not exhibiting it as much as the other then, it becomes negatively linked to value co-creation bringing about value co-destruction making one party not benefit from the service.

Further, service interaction between service provider and their customers is crucial in determining the lasting relationship and trust between the two parties. For service rendering to be complete there must be some sort of communication or interaction from one party (customer) to the (service provider). Data analysis outcome supports the service interaction hypothesis which is positively associated with value co-creation. Payne, & Storbacka, (2015) discussed the importance of service interaction between customers and service providers as being a critical factor in the co-creation of value in a business context.

Personal conditions as proved by the data analysis also result in positive outcomes when linked to hedonic values for students. This is because Personal Circumstances such as mental and physical conditions of customers and service providers of hospitality facilities as well as their household situations also recognized differently influence on their collaborative effort in co-creating value. Personal conditions of people vary depending on certain circumstances which they are faced with and this determines the level of their participation and contribution to value co-creation. When people are of good personal conditions being physical or psychological they bring out their best in co-creating value for themselves.

Also, the value co-creation hypothesis used in the study shows that it has a significant influence on hedonic values. It is recognized that customer’s hedonic values are mostly satisfied or achieved through interaction and experiences of service offering which can only be attained through value co-creation. The pleasure and excitement customers get when experiencing services especially in the hospitality sector is possible through the individuals own contribution as well as the service provider’s effort to make it possible and when this is being dome we say value has been co-created.

Finally, the outcome of the hedonic value hypothesis proved to be positively connected to customer satisfaction since in most cases value co-creation and hedonic values seek to provide enjoyable and personalized experiences which are tailored to meet specific preferences and needs of customers and giving them an increased satisfaction. When customers value for money are met and enjoyed they become satisfied which further makes them loyal to your services.

Conclusion

The study focused on how value co-creation influences hedonic values in the hospitality industry where by some four factors such as resources availability, commitment, service interaction, and the personal condition which cause value co-creation to have a direct causal effect on customer’s hedonic values when visiting hospitality facilities. This is a new phenomenon which isn’t much talked about because most scholars do not focus much on hedonism in the hospitality sector. Therefore, scholarly attention is very rare in this context.

As a contribution to this field, this study fills the gap in the literature of the effect value co-creation and hedonic values have on each other context which is new and underexplored study area in the hospitality context. Further, it broadens the understanding of both the concepts of value co-creation and customer satisfaction as the causal effect of one another. As both practical and statistically proven, it provides the insights for stakeholders such as employees, managers, owners and customers to optimize collaborative value co-creating and hedonism in the hospitality industry.

Implications and Contributions

The policy, practical, and scientific implications of the study's findings and interpretations are summed up here. Implications for theory highlight the study's contributions to the expanding amount of literature on hedonic values and value co-creation in the hospitality industry. Under the implications for researchers, the study's contributions to improving the methodology of past studies on hedonic values and value co-creation are explored. The study calls for stakeholders to identify factors such as availability of certain resources in the facility, commitment of employees, quality service interaction between workers and customers as well as taking into consideration the personal conditions of workers and customers to encourage participation in co-creating values which will leave a long-lasting experience in the minds of customers as well as giving them satisfaction in their usage of such hospitable services.

Limitations and Future Studies

The study found that the effectiveness of customer and employee participation in co-creating value is not only dependent on the four factors provided because commitment was found to be insignificantly linked to value co-creation making it a limitation since the authors attempted to prove commitment to be positively linked to value co-creation.

This study is based on information obtained from 256 respondents chosen based on convenience. Therefore, it may not be enough to generalize these findings to the whole country’s context. Therefore, there are avenues for future researchers to investigate more in-depth literature of hedonic values as well as value co-creation since we tackled just a fraction of the enormous literature on the two areas. As such, a further study using other literature, orientation and methods may bring out other results. Despite our study limitation, we make key contributions to research and thus provide key directions for attention of future.

References

Anwar, G., & Abd Zebari, B. (2015). The Relationship between Employee Engagement and Corporate Social Responsibility: A Case Study of Car Dealership in Erbil, Kurdistan. International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies, 2(2), 45.

Anwar, G., & Surarchith, N. K. (2015). Factors Affecting Shoppers’ Behavior in Erbil, Kurdistan–Iraq. International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies, 1(4), 10.

Anwar, K. (2016). Comparison between cost leadership and differentiation strategy in agricultural businesses. Custos E Agronegocio on Line, 12(2), 212-231.

Anwar, K. (2017). Analyzing the conceptual model of service quality and its relationship with guests satisfaction: a study of hotels in erbil. The International Journal of Accounting and Business Society, 25(2), 1-16.

Armstrong, G., Adam, S., Denize, S., & Kotler, P. (2014). Principles of marketing. Pearson Australia.

Ayeh, J. K., Au, N., & Law, R. (2013). Predicting the intention to use consumer-generated media for travel planning. Tourism management, 35, 132-143.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Azeem, S. M. (2010). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment among employees in the Sultanate of Oman. Psychology, 1(4), 295-300.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ballantyne, D., & Varey, R. J. (2006). Creating value-in-use through marketing interaction: the exchange logic of relating, communicating and knowing. Marketing theory, 6(3), 335-348.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chathoth, P. K., Ungson, G. R., Harrington, R. J., & Chan, E. S. (2016). Co-creation and higher order customer engagement in hospitality and tourism services: A critical review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(2), 222-245.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chen, W., & Li, X. (2012). The impact of staffing levels on hotel service quality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(1), 14-22.

Cova, B., & Dalli, D. (2009). Working consumers: the next step in marketing theory?. Marketing theory, 9(3), 315-339.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). The domain of creativity.

Dedeoglu, B. B., Balıkçıoğlu, S., & Küçükergin, K. G. (2016). The role of touristsʼ value perceptions in behavioral intentions: The moderating effect of gender. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(4), 513-534.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Druker, J., & Simons, R. (2013). Managing resources to deliver value in hospitality and tourism. Routledge.

Duchek, S. (2020). Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Business research, 13(1), 215-246.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Frow, P., & Payne, A. (2011). A stakeholder perspective of the value proposition concept. European journal of marketing, 45(1/2), 223-240.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Frow, P., Nenonen, S., Payne, A., & Storbacka, K. (2015). Managing co‐creation design: A strategic approach to innovation. British journal of management, 26(3), 463-483.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Galvagno, M., & Dalli, D. (2014). Theory of value co-creation: a systematic literature review. Managing service quality, 24(6), 643-683.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gebauer, H., Johnson, M., & Enquist, B. (2010). Value co‐creation as a determinant of success in public transport services: A study of the Swiss Federal Railway operator (SBB). Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 20(6), 511-530.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and individual differences, 102, 74-78.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Goulet-Pelletier, J. C., & Cousineau, D. (2018). A review of effect sizes and their confidence intervals, Part I: The Cohen’sd family. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 14(4), 242-265.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Grönroos, C., & Ravald, A. (2011). Service as business logic: implications for value creation and marketing. Journal of service management, 22(1), 5-22.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing theory and Practice, 19(2), 139-152.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European business review, 31(1), 2-24.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 43, 115-135.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kabadayi, S., & Price, K. (2014). Consumer–brand engagement on Facebook: liking and commenting behaviors. Journal of research in interactive marketing, 8(3), 203-223.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lusch, R. F., & Nambisan, S. (2015). Service innovation. MIS quarterly, 39(1), 155-176.

Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2006). Service-dominant logic: reactions, reflections and refinements. Marketing theory, 6(3), 281-288.

Matthing, J., Sandén, B., & Edvardsson, B. (2004). New service development: learning from and with customers. International Journal of service industry management, 15(5), 479-498.

Miao, L., Lehto, X., & Wei, W. (2014). The hedonic value of hospitality consumption: Evidence from spring break experiences. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 23(2), 99-121.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of marketing, 58(3), 20-38.

Morosan, C. (2018). An empirical analysis of intentions to cocreate value in hotels using mobile devices. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(4), 528-562.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

O’Hern, M. S., & Rindfleisch, A. (2010). Customer co-creation: a typology and research agenda. Review of marketing research, 6(1), 84-106.

Ostrom, E. (2010). Beyond markets and states: polycentric governance of complex economic systems. American economic review, 100(3), 641-672.

Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., & Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 36, 83-96.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2000). Co-opting customer competence. Harvard business review, 78(1), 79-90.

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2003). The new frontier of experience innovation. MIT Sloan management review.

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co‐creating unique value with customers. Strategy & leadership, 32(3), 4-9.

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). The future of competition: Co-creating unique value with customers. Harvard Business Press.

Prebensen, N. K., & Xie, J. (2017). Efficacy of co-creation and mastering on perceived value and satisfaction in tourists' consumption. Tourism Management, 60, 166-176.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ramaswamy, V., & Gouillart, F. (2010). Building the co-creative enterprise. Harvard business review, 88(10), 100-109.

Ranjan, K. R., & Read, S. (2016). Value co-creation: concept and measurement. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 44, 290-315.

Russell, J. A., & Pratt, G. (1980). A description of the affective quality attributed to environments. Journal of personality and social psychology, 38(2), 311.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sarmah, B., Kamboj, S., & Rahman, Z. (2017). Co-creation in hotel service innovation using smart phone apps: an empirical study. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(10), 2647-2667.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shmueli, G., & Koppius, O. R. (2011). Predictive analytics in information systems research. MIS quarterly, 553-572.

Solakis, K., Pena-Vinces, J., & Lopez-Bonilla, J. M. (2022). Value co-creation and perceived value: A customer perspective in the hospitality context. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28(1), 100175.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Solakis, K., Pena-Vinces, J., Lopez-Bonilla, J. M., & Aguado, L. F. (2021). From value co-creation to positive experiences and customer satisfaction. A customer perspective in the hotel industry. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 27(4), 948-969.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stinglhamber, F., Marique, G., Caesens, G., Desmette, D., Hansez, I., Hanin, D., & Bertrand, F. (2015). Employees’ organizational identification and affective organizational commitment: An integrative approach. PloS one, 10(4), e0123955.

Straub, D. W., Gefen, D., & Recker, J. (2022). Quantitative research in information systems. Association for Information Systems (AISWorld) Section on IS Research, Methods, and Theories.

Vargo, S. L. (2008). Customer integration and value creation: paradigmatic traps and perspectives. Journal of service research, 11(2), 211-215.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of marketing, 68(1), 1-17.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2011). It's all B2B… and beyond: Toward a systems perspective of the market. Industrial marketing management, 40(2), 181-187.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2016). Institutions and axioms: an extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of marketing Science, 44, 5-23.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vargo, S. L., & Sindhav, B. G. (2014). Special Issue: “Service-Dominant Logic and Marketing Channels/Supply Chain Management”. Journal of Marketing Channels, 21(4), 294–295.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vargo, S. L., Akaka, M. A., & Vaughan, C. M. (2017). Conceptualizing value: a service-ecosystem view. Journal of Creating Value, 3(2), 117-124.

Vargo, S. L., Maglio, P. P., & Akaka, M. A. (2008). On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. European management journal, 26(3), 145-152.

Vargo, S.L. and Lusch, R.F. (2004), “Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 68 No. 1, pp. 1-17.

Vargo, S.L. and Lusch, R.F. (2008), “Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 1-10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wang, D., & Lu, L. (2016). The impact of physical resources on service quality in the hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(4), 739-756.

Zhang, T., Lu, C., Torres, E., & Chen, P. J. (2018). Engaging customers in value co-creation or co-destruction online. Journal of Services Marketing, 32(1), 57-69.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 12-Oct-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14091; Editor assigned: 13-Oct-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-14091(PQ); Reviewed: 29-Dec-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-14091; Revised: 29-Feb-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14091(R); Published: 04-Mar-2024