Research Article: 2026 Vol: 30 Issue: 2

Factors Affecting Millennials' Consumer Behavioral Intention to Adopt Chatbots: An Empirical Validation

Sameh Tebourbi, Sfax University

Romdhane Khemakhem, Sfax University

Citation Information:Tebourbi, S., & Khemakhem, R. (2026) Factors affecting millennials’ consumer behavioral intention to adopt chatbots: an empirical validation. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 30(2), 1-13.

Abstract

Despite the wide popularity of chatbots, little is known about the motivational drivers of how and why consumers engage with chatbots. In addition, no study has yet explored whether millennial’ consumers favor an online social presence in chatbots and to what extent this is decisive for their purchasing experience. The purpose of this study is to identify the factors which influence millennials customers’ behavior intention to use chatbots in the Tunisian context by applying the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 and the social presence theory. The method approach employed was a quantitative web-based survey. The data was collected from 340 users of chatbot applications. The proposed model was tested and confirmed using the structural equation model. The finding shows that performance expectancy, effort expectancy, hedonic motivation, and social presence significantly influence behavioral intention to adopt Chabot by millennial’ consumers. The findings provide useful insight to add to the frame of extant literature and to discuss the possible directions of research.

Keywords

Chatbot, The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology, The Social Presence Theory, Y Generation, Structural Equation Model

Introduction

Digital technology has touched several areas like business, education, and industry. However, artificial intelligence constitutes an important element of technological developments. The emergence of chatbot applications that are part of artificial intelligence and are available for various platforms (Richard et al., 2019).

In this regard, artificial intelligence-based messaging solutions, namely conversational bots, represent one of the first stepping stones in order for companies to become faster, more efficient, and more able to provide customers with relevant and personalized experiences.

According to Cicco et al., (2020), “Platforms, artificial intelligence, and the increased use of messaging apps are the major factors driving the chatbot industry forward.”.

Indeed, chatbots can be perceived as the perfect illustration of the development and implementation of customer-centric artificial intelligence that mimics human behavior, which has a wide range of applications in various fields, such as education, healthcare, financial services, and e-commerce (Toader et al., 2020). “Thus, in many cases they replace employees in customer service transactions, who, in the context of interaction with customers, answer their questions, propose solutions, and redefine suggestions according to preferences and choices” (Dash & Bakshi, 2019; Gatzioufa et al., 2022).

Actually, chatbots have been used for providing customers with enjoyment and useful information, easily and fast, with personalized help, saving both costs and manpower (Radziwill & Benton, 2017).

In addition, “Chatbots are currently grabbing the attention of a growing number of researchers, addressing their interest in visual-conversational cues and interactivity of chatbots” (Go & Sundar, 2019; Chattaraman et al., 2019) “as well as their potential role in enhancing customers’ satisfaction” (Chung et al., 2018) and “company perceptions” (Araujo, 2018). “This is particularly true for millennials, as technology is significantly integrated into their daily lives” (Moore, 2012; Cicco et al., 2019).

Despite the continuous growth and wide popularity of chatbots, unfortunately, little is known about the motivational drivers of how and why consumers engage with chatbots (Dinh & Park, 2022). To fill these gaps in the literature by revealing the underlying mechanism of chatbot adoption, utilitarian motivation seeks to attain resources and/or reduce the risk.

Currently, the main challenge with chatbots concerns interpretation problems. In most cases, chatbots cannot respond to more specific or complex requests or do not always understand what the consumer is asking (Cicco et al., 2020). Additionally, a lack of awareness about the results of using chatbots in their various applications could pose a threat to the growth of this market (Cicco et al., 2020). According to Cicco et al., (2020), no study has yet explored whether millennial consumers favor an online social presence in chatbots and to what extent this is decisive for their purchasing experience.

There are various theories and models that explain the acceptance and adoption of new technologies. In this research, the UTAUT2 model is a well-established model for understanding the factors that guide user beliefs for the adoption and acceptance of new technology (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Hence, the problem of this research revolves around the following questions: Which factors can affect millennials customers’ behavior intention to use chatbots in the Tunisian context?

The target of this work is therefore two-fold. The first step is to present a theoretical overview of the basic concepts of our study, namely UTAUT2 theory, the social presence theory, and chatbots. In the second step, we will provide an explanation of the relation of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence on behavioral intention to adopt a chatbot and aim to reveal underlying hedonic motivation by highlighting the role of social presence and its impact on consumer intention.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The Chatbot

Reasoning by analogy is a scientific research topic in which several researchers have taken an interest. “Chatbots are natural language computer programs that simulate human language and interact with customers with the help of a text-based dialog” (Zumstein & Hundertmark, 2017).

“The attention focus on chatbots is mostly linked to significant developments in computing technology and the wide acceptance of smartphone messaging apps” (Sugumar et al., 2021)

Recently, the chatbot began to appear in response to the needs of consumers, particularly millennials (Cicco et al., 2020) because technology is widely integrated into their daily lives and thanks to the real-time nature that allows consumers to get instant informal responses to their queries (Mero, 2018).

Particularly, today’s chatbots providing customer service are low-end feeling AI applications, can learn and adapt only to a minimal degree, and do some relationalization, but in a rather mechanical way (Huang & Rust, 2021). Scholars and designers have aimed to enhance the humanness of chatbots for a long time (Roy & Naidoo, 2021), and have found that adding human attributes to chatbots can enhance positive experiences and trigger social and emotional connectedness (Adam et al., 2021). According to (Brandtzaeg & Følstad, 2017)

Chat agents serve a variety of use cases, including consumer service, emotional support, knowledge, social support, entertainment, and interaction with other people or machines.

The latest advancements in AI and machine learning are what propel chatbots (Brandtzaeg & Følstad, 2017). These advancements offer significant advancements in the comprehension and examination of natural languages, encompassing machine translation advancements (Warwick et al., 2016). In addition, the increasing utilization use of messaging applications and mobile internet has increased the use of chatbots (Brantzaeg & Følstad, 2017). Chat bots are useful in many different contexts, such as customer service, knowledge, emot ional support, social support, and communication with devices or other individuals (Brandtzaeg & Følstad, 2017). So, the Chatbot solution is expected to help consumers with faster and accurate information (Collier & Kimes, 2012). Hence, that’s why we chose UTAUT2 and social presence theory as the base theories for the research study and to more understand human-chatbot interactions.

The following subsections discussed the development of the hypotheses to explain behavioral intention to adopt chatbots.

Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2)

There are several well-established theories in Information Systems (IS) research for the adoption of technology (Wade & Hulland, 2004). The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2) (Venkatesh et al., 2012) is one of the most popularly referenced theoretical models for the adoption of technology. The UTAUT theory has five main constructs, namely performance expectancy, social influence, effort expectancy, and facilitating conditions, which impact the behavioral intention of customers to accept and use technology.

Venkatesh, Thong, & Xu, (2012) have extended the UTAUT model and included two additional constructs: Hedonic motivation and habit. The extensions proposed in UTAUT2 produced a substantial improvement in the variance explained in behavioral intention and technology use (Venkatesh et al., 2012).

In the present study, the facilitating conditions were excluded because chatbot use requires no assistance of any kind.

Effort Expectancy (EE)

Effort expectancy is defined as “the extent to which technology provides easy service to its users” (Raman & Don, 2013). In the context of chatbots, “effort expectancy encompasses the notion of the customers that the chatbot software is intuitive enough to provide information to its customers without much effort from them” (Sugumar et al., 2020).

Indeed, “the chatbot software is intuitive enough to provide information to its customers without much effort from them” (Sugumar et al., 2020).

In other words, effort expectancy determines the extent to which the chatbot system would enable the user to better perform the job and enhance the performance. According to Venkatesh et al., (2012), effort expectancy has been found to be a significant variable in several studies and proven to work as a predictor of behavioral intention to adopt new technology. Consequently, he will be willing to use chatbots for future services as well. Hence, we hypothesize.

H1: Millennial customers’ effort expectancy has a significant influence on the behavioral intention to adopt chatbots.

Performance Expectancy (PE)

Performance expectancy is defined as “the degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help him or her to attain gains in job performance” (Venkatesh et al., 2007). The belief of the users that technology such as chatbots is useful for them to increase their efficiency and productivity.

Previous research has elicited that performance expectancy is a significant predictor of behavioral intention (Venkatesh et al., 2012). However, the chatbots services can be help users especially millennials to seek information, transact online and creates a perception of improved experience resulting in continuance intention (Nguyen et al., 2021).

In line with (Gansser & Reich, 2021) the performance expectancy played a significant role in explaining behavioral intention and use behavior towards artificial intelligence products. Based on the above justification, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Millennial customer’s performance expectancy has a significant influence on the behavioral intention to adopt chatbots.

Social Influence (SI)

Social influence is “the degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe he or she should use the new system” (Venkatesh et al., 2007). SI has emerged as being significant regarding behavioral intention to use certain technology (Moore & Benbasa, 1991). Although a number of studies have explored human–chatbot interactions, fewer of these studies have investigated how behavioral intention and adoption behavior are influenced by an individual's positive or negative feelings (Toader et al., 2020; Taylor & Todd, 1995).

According to Himanshu Joshi, (2021), in technology adoption, it is believed that the social influence, the stronger, would be the behavioral intention. “The role of social influence in many fields is even more pronounced as people are wary of revealing their personal information to chatbots. They need assurance from their friends and acquaintances whose opinion they value to develop the confidence in using chatbots for efficient and secured service” (Sugumar et al., 2021). Therefore, this reasoning leads to hypothesizing the following:

H3: Millennial customers social influence has a significant influence on the behavioral intention to adopt chatbots.

Hedonic Motivation (HM)

Hedonic motivation is “an enjoyment or happiness resultant from using a hedonic technology and plays a significant part in determining new technology adoption” (Brown & Venkatesh, 2005). According to Anderson et al., (2014), the perception of enjoyment that arises from the experience of the technology is the hedonic motivation.

In this regard, chatbots can converse with consumers in an automatic and interactive manner, whereas older one-way technologies such as websites cannot. As a result, consumers can achieve a true sense of joy, entertainment, playfulness, and escapism when interacting with chatbots (Almahri, 2019). On the other hand, (Koufaris, 2002) “has demonstrated that hedonic motivation leads to positive attitudes in the online shopping environment.”.

Drawing from prior works in information systems literature and digital marketing, hedonic motivation is expected to provide user gratification, which may influence consumers to adopt and use the new technology (van der Heijden, 2004). Based on the literature, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Millennial consumers’ hedonic motivation has a significant influence on their behavioral intention to adopt chatbots, mediated by social presence.

Social Presence

Social presence is defined as ‘the feeling of being with another.’ It is the extent to which the human characteristics infused in the chatbot provide its customers with a feeling of emotional closeness and/or social connectivity (Bente et al., 2008).

In doing so, this research focuses on a social relationship perspective and social presence in the virtual context. Brandtzaeg & Følstad, (2017) showed that “chatbots are not merely a productive tool but can also be seen as a more personal source of interaction and convey social value.” A considerable body of study has focused on human–chatbot interactions (Hill et al., 2015).

The computer-as-social-actor’s paradigm suggests that although people fully acknowledge chatbots’ non-human nature, they still tend to treat chatbots with social presence as if they were human (Lee & Nass, 2004). In such situations, because people’s mental schema about chatbots is congruent with their preexisting schema about humans, they are likely to treat chatbots more favorably (Aggarwal & McGill, 2007). Moreover, people have a basic need for social relatedness. (Ryan & Deci, 2017), and chatbots with high social presence possess characteristics (e.g., warmth and sociability) required to facilitate high-quality relationships (Canevello & Crocker, 2010). Thus, chatbots’ social presence can satisfy people’s need for relatedness, motivating them to accept and use chatbots. Likewise, past research has shown that social presence is positively associated with chatbot adoption (Chuhg et al., 2020).

Li & Mao, (2015) have examined antecedents of chatbots’ social presence other than design cues. They found that chatbots’ hedonic values (e.g., perceived engagement and perceived enjoyment) positively influence their social presence.

Hence, we hypothesize:

H5: A chatbot’s social presence has a significant influence on the behavioral intention to adopt the chatbot service.

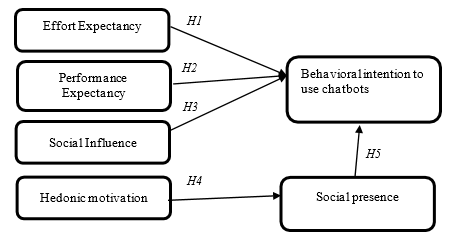

Figure 1 shows the proposed conceptual model composed by five variables of the UTAUT 2 model (performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, hedonic motivation and behavioral intention). An extension of the model has been proposed by the inclusion of one additional variable in the chatbot context (social presence).

FIGURE 1 CONCEPTUAL MODEL.

Methodology

Data Collection

The quantitative approach will be adopted as part of our research to test the different hypotheses and meet the objectives. Data collection will be carried out by a questionnaire survey that was conducted among 340 chatbot users in online shopping. Everard et al., (2003) propose a sample size ranging from 5 to 10 observations. Thus, we have multiplied the number of items 5 times.

Respondents were invited to browse the site, add a product to the shopping cart, and then seek to contact someone on the site/Facebook page to ask one or more questions.

The final sample was collected of 41% of men and 59% of women with an average age between 27 and 42 years old. This looks reasonable given that, according to Cicco et al., (2020), this channel is particularly used by young people and especially Generation Y because technology is widely integrated into their routines.

Participants were recruited using non-random sampling. An essential condition for participating in the survey was to have a Facebook Messenger account (necessary to start interaction with the chatbot). As expected, most respondents reported using messaging apps daily. The survey recorded the respondents' usage behavior of the chatbot.

Measuring Scales

The present study adopted validated scales for all variables with little change. For all measures, responses were on a 5-point Likert scale (1 "Disagree"; 5 "Strongly agree"). The vocabulary of these scales has been adapted to the context of chatbots. All variables related to UTAUT were adapted from the research of Venkatesh, (2012).

The measurements of the different variables of the study the present study adopted validated scales for all variables with little change. For all measures, responses were on a 5-point Likert scale (1 "Disagree"; 5 "Strongly agree"). The vocabulary of these scales has been adapted to the context of chatbots. All variables related to UTAUT were adapted from the research of Venkatesh (2012). The measurements of the different variables of the study are outlined in the following Table 1.

| Variables | Dimensions | Items number | Authors | Measurement scales |

| Variables related to UTAU2 | Effort expectancy | 4 | Venkatesh (2012) | 5-point Likert scale (1 "Disagree"; 5 "Strongly agree") |

| Performance expectancy | 4 | |||

| Social influence | 3 | |||

| Hedonic motivation | 5 | Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Grifn, M. (1994) | ||

| Behavioral intention | 3 | Venkatesh (2007) | ||

| Social presence | Social presence | 4 | Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2004) |

Table 1 MEASUREMENT OF DEPENDENT AND INDEPENDENT VARIABLES

Method of Data Analysis

In order to assess the model and validate the structures of the relationships between its variables, the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), which is “a comprehensive statistical approach to testing hypotheses about relations among observed and latent variables” will be adopted (Hoyle, 1995) using SPSS 23 and AMOS 23 software.

SEM was applied to analyze the proposed research model because such an approach has higher statistical power which is especially useful for exploratory research—and it better predicts key driver constructs. This technique employs a two-stage process starting with the assessment of the measurement model (reliability and validity) and the estimation of the structural model (testing the hypothesized relationships).

Results

The Psychometric Quality of Scales

The research framework consists of five exogenous variables (effort expectancy, performance expectancy, social influence, hedonic motivation, and social presence of chatbots) and one endogenous variable (behavioral intention to use).

In this study the internal consistency was examined using Cronbach's alpha. value for all constructs was found to exceed 0.67, which indicates that the measurement is reliable (Lin & Huang, 2008). Each construct shows Cronbach alpha readings of acceptable values of above 0.60 (Nunnally, 1970) (Table 2).

| Concepts | Original items | Total mean | Standard deviation | Items after EFA | Cronbach alpha CFA |

| Effort Expectancy (EE) | 4 | 4,14 | 1,267 | ,788 | 0,855 |

| 4,24 | 1,187 | ,830 | |||

| 4,27 | 1,168 | ,897 | |||

| Performance Expectancy (PE) | 4 | 4,20 | 1,189 | 0,97 | 0,778 |

| 4.27 | 1.37 | 0,830 | |||

| 4,27 | 1,168 | 0,897 | |||

| Social influence (SI) | 3 | 4,18 | 1,444 | 0,632 | 0.632 |

| 4.22 | 1.2 | 0.926 | |||

| 0.587 | |||||

| Hedonic Motivation (HM) | 5 | 3,39 | 0,786 | 0,835 | 0.878 |

| 3,51 | 0,745 | 0,872 | |||

| 4,17 | 1,079 | 0,733 | |||

| Social Presence of chatbots (SP) | 4 | 4.225 | 1 | 0.679 | 0.745 |

| 4.216 | 1.039 | 0.974 | |||

| 4.875 | 1.034 | 0.871 | |||

| Behavior Intention to adopt chatbots service (BI) | 3 | 3.21 | 1.873 | 0.547 | 0.67 |

| 3.58 | 1.068 | 0.784 | |||

| 3.97 | 1.981 | 0.941 |

Table 2 THE PSYCHOMETRIC QUALITY OF SCALES.

Construct Reliability

We examined the estimated path coefficients of the structural model. The reliability of the scales is satisfied (ρ of Jöreskog and α of Cronbach> 0.7) (Appendix 1).

Convergent Validity

A convergent validity test was conducted to analyze the point to which various substances used to quantify the hypothesized theories are gauging the same notion. Composite reliability and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were observed to carry out convergent validity, where AVE is the ratio of construct variance to the total variance among indicators (Hair et al., 1998). “Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is the average VE value of two constructs.” “Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should be more than 0.5” (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) This condition was found to be satisfied. The results show that the convergent validity is satisfied (Table 3).

|

|

AVE |

|

Effort Expectancy (EE) |

0.587 |

|

Performance Expectancy (PE) |

0.565 |

|

Social influence |

0.561 |

|

Hedonic Motivation (HM) |

0.735 |

|

Social Presence of chatbots (SP) |

0.56 |

|

Behavioral Intention to use chatbots (BI) |

0.72 |

Table 3 CONVERGENT VALIDITY INDICATORS (N=340)

Discriminant Validity of Constructs

According to Fornell & Larcker, (1981), “Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should be more than the correlation squared of the two constructs to support discriminant validity”.

To assess discriminant validity, Fornell & Larcker, (1981) criterion – latent variable correlations and cross- loading were considered. As shown in Table 3, the square root of theAVE is higher than the correlation between variables, supporting discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2011). In our case, all the diagonal elements which the square root of the AVE are more than the inter-item correlations reported below the diagonal for the corresponding constructs (Table 4).

|

Effort Expectancy (EE) |

Performance Expectancy (PE) |

Social influence (SI) |

Hedonic Motivation (HM) |

Social Presence of Chatbots (SP) |

Behavioural Intention to use chatbots (BI) |

|

|

Effort Expectancy (EE) |

0.766 |

|||||

|

Performance Expectancy (PE) |

0.54 |

0.751 |

||||

|

Social Influence (SI) |

0.52 |

0.58 |

0.6 |

|||

|

Hedonic motivation (UM) |

0.669 |

0.48 |

0.856 |

|||

|

Social Presence of chatbots (SP) |

0.52 |

0.74 |

0.472 |

0.7 |

0.748 |

|

|

Behavioral to adopt chatbots (BI) |

0.421 |

0.361 |

0.358 |

0.425 |

0.635 |

0.848 |

Table 4 DISCRIMINATING VALIDITY INDICATORS OF BUILDINGS (N=340)

As the conclusion, we notice that the conditions for both convergent and discriminant validity were met, the measurement model was considered significant.

Hypothesis Test

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used. Figure 2 indicates that the structural model had good fit indice (Appendix 2).

To judge a relationship as meaningful, it must verify that the CR is higher than 1.96 with a significant p (p must be less than 5%). In order to advance the understanding of the relationship between the variables, we tested the mediating effects of the direct and indirect effects of interaction style on attitude towards the chatbot through social presence, EE, PE, IS and HM.

The Table 5 shows that CR range is higher than 1.96.

|

Estimate |

SE |

CR |

P |

|||||

|

HI |

BI |

<--- |

EE |

2,431 |

0,701 |

3,467 |

*** |

Supported |

|

H2 |

BI |

<--- |

PE |

1,299 |

0,321 |

4,052 |

*** |

Supported |

|

H3 |

BI |

<--- |

SI |

1,204 |

0,090 |

0,258 |

,064 |

Rejected |

|

H4 |

SP |

<--- |

HM |

0.314 |

0,874 |

2.314 |

*** |

Supported |

|

H5 |

BI |

<--- |

SP |

0.212 |

1.371 |

1.98 |

*** |

Supported |

|

Note: ***means that p must be less than 5% |

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

Table 5 HYPOTHESIS TEST.

Results of the Mediation Test

We conducted the mediation test following the classical approach of Baron & Kenny, (1986). The results are presented in Table 6. direct and indirect effects was analysed based on bootstrap procedures (2000 samples) and bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval (90%). as indirect effects are significant (β=.137, P<.05), we can support that social influence mediates the relationship between hedonic motivation and the behavioral intention to adopt the chatbot service, thus this relation is supported.

|

|

Direct effect |

Indirect effect |

Total effect |

|

HM>SP>BI |

0.003 |

0.137* |

0.132 |

|

Note: *<.05 |

|||

Table 6 MEDIATION TEST

Discussion

Analysis results indicate that the variables performance expectancy, effort expectancy, hedonic motivation, and social presence are essential variables that influence the purpose of adopting chatbots.

First, performance expectancy was found to have a direct, significant impact on behavioral intention to use a chatbot. Previous studies have found similar results (Venkatesh et al., 2012; Wang, 2008; Borrero et al., 2014). Indeed, performance expectancy is one of the most powerful predictors of intention built into the UTAUT model. In addition, it is supposed to provide assistance to different fields (regardless of their level).

Hence, its recommended to millennial customers to adopt chatbot to answer their frequently asked queries and get status of their past requests. Users will get familiarized to using chatbot only when they can perform these tasks with adequate feat.

Chatbots are a way to get speedy data on the subject user is inquisitive about and the capacity to realize it quicker plays a vital part in buyers embracing chatbots for monetary administrations.

Second, the study found that Effort expectancy affects behavior intention to adopt the Chatbot. this result is equivalent to past studies (Gaitán, Peral, & Ramón, 2015; Lakhal, Khechine, & Pascot, 2013). Indeed, the chatbot system is perceived to be easy and leads to higher adoption intention. This research rejects the influence of social influence on behavioral intention to adopt chatbots.

This result is surprising and contradicts the results of previous research, whether in the context of UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003), it was observed that the chatbot system became popular only when SI positively affected behavior intention to use it. The new variable introduced by Venkatesh et al., (2012) in the UTAUT2 model is hedonic motivation, which has a positive influence on intention to use a chatbot. This finding was supported by some previous research, such as Li & Mao, (2015). The study results proved that hedonic motivation of chatbot service increases intent to adopt it. student when using this platform, they feel an enjoyable time, like an escape from reality and a sense of adventure.

Finally, the results also indicate that social presence has a positive effect on behavioral intention to use chatbots (Oliveira, 2021) and have found similar findings.

Being the positive link between social presence and behavioral intention of using the chatbot, online practitioners should offer resources to developing virtual assistants capable of providing consumers an entertaining, interactive, easy, and social experience.

This research enriches the literature with an integrated model that includes the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology on UTAU2 (Venkatesh et al., 2012) and social presence theory.

The present study further contributes to the literature on social presence theory and chatbot relationships by demonstrating that a chatbot showing psychological closeness that employs warm and friendly conversation can be a fundamental trigger for generating a better social presence experience (Cyr et al., 2007).

Implications for Research and Practice

The study extends the literature on various factors as well as the literature on chatbot adoption by giving a model that provides a theoretical basis for obtaining insights into the predictors of chatbot adoption intentions. The research indisputably points out the factors that are crucial drivers for acceptance of chatbots and encourages professionals, chatbot retailers, and engineers to take these factors seriously. Companies could implement it while it could be alluring for companies to implement it. Hence, companies need to do field studies before the implementation phase, as the desires and driving factors for consumers may vary across industries.

Conclusion

As a final note, it is noteworthy that the overall objective of this paper was to highlight the emerging phenomenon of chatbots due to advancements in technology innovations like artificial intelligence. So, after analyzing collected data, we find that all hypotheses are accepted except the effect of social influence is not supported. It attempts to explain the specificities of behavioral intention to adopt chatbots among millennials in the Tunisian context. Although this concept is a recent field that offers several opportunities to companies, managers must play a nodal and catalytic role in the involvement and integration of technology news in their strategic orientation.

Specifically, this work draws the attention of the managers to deduce that the integration of that performance expectancy effort, expectancy, and hedonic motivation is quite promising because they significantly affect the behavioral intention to use chatbots by the Y generation.

Indeed, this study enriches the literature on innovative marketing channels through an analysis of the variables related to UTAUT2 that play a major role in human–chatbot interaction for business purposes. In this regard, the managerial implication of this research is that chatbot providers can design visual and conversational elements of chatbots that seem to enhance their effectiveness for younger segments of the customer base.

Finally, we would assert that the current research work is a step that may be built upon and extended and taken further as it opens additional fruitful lines of investigation and offers valuable research directions. Indeed, in future research we may develop a methodological and empirical framework aimed at determining the most decisive measurement indicators associated with the factors that affect technology adoption, especially consumer behavior and the use of chatbots in the Tunisian context.

The Limits and Future Research

Promising as it seems, this study, displays certain limitations which opens new perspectives for future study.

First gaps are inherent to the nature of the sample. Indeed, the sample is limited to a specific young cohort (the Millennials), so the sample size for the older generation was relatively small, and the number of participants was not balanced across the three generational cohorts.

Therefore, they are not a broad representation of the entire population, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. However, future research could use a systematic sampling approach to collect a more balanced sample, and a comparison between the attitudes of the millennial user and other generations could add to the existing body of knowledge on chatbots.

Secondly, our research was limited to four constructs adopted from the UTAUT model. Since The UTAUT2 model can additional constructs like risk, trust, habit, price value, etc. which could help in improving the psychometric quality of the result. Then, future research may include other variables such as perceived intelligence or perceived safety to extend the model.

Thus, in order to validate the results, future research could integrate more heterogeneous samples to better understand the factors that affect behavior intention to use chatbot services.

Subsequent research may also widen this field of study by tackling, for example, the role played by utilitarian aspects in terms of improving behavioral adoption and intention to use the chatbots.

References

- Adam, M., Wessel, M., & Benlian, A. (2021). Chatbots in customer service and their effects on user compliance. Electronic Markets, 31, 427–445.

- Aggarwal, P., & McGill, A. L. (2007). Is that car smiling at me? Schema congruity as a basis for evaluating anthropomorphized products. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(4), 468–479.

- Borrero, J. D., Yousafzai, S. Y., Javed, U., & Page, K. L. (2014). Expressive participation in internet social movements: Testing the moderating effect of technology readiness and sex on student SNS use. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 39–49.

- Brandtzaeg, P. B., & Følstad, A. (2017). Why people use chatbots. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 10673 LNCS, 377–392.

- Brown, S. A., & Venkatesh, V. (2005). Model of Adoption of technology in households: A baseline model test and extension incorporating household life cycle. MIS Quarterly, 29(3), 399–426.

- Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81.

- Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2010). Creating good relationships: Responsiveness, relationship quality, and interpersonal goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(1), 78.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collier, J. E., & Kimes, S. E. (2013). Only if it is convenient: Understanding how convenience influences self-service technology evaluation. Journal of Service Research, 16(1), 39–51.

- Chowdhery, A., Narang, S., Devlin, J., Bosma, M., Mishra, G., Roberts, A., & Fiedel, N. (2022). Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways.

- Dinh, C.-M., & Park, S. (2022). How to increase consumer intention to use chatbots? An empirical analysis of hedonic and utilitarian motivations on social presence and the moderating effects of fear across generations. Electronic Commerce Research, 1–41.

- Chung, E., Subramaniam, G., & Dass, L. C. (2020). Online learning readiness among university students in Malaysia amidst COVID-19. Asian Journal of University Education, 16(2), 45–58.

- De Cicco, R., & Silva Alparone, F. (2020). Millennials' attitude toward chatbots: An experimental study in a social relationship perspective. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 48(11), 1213–1233.

- Collier, J. E., & Kimes, S. E. (2012). Only if it is convenient: Understanding how convenience influences self-service technology evaluation. Journal of Service Research, 16(1), 39–51.

- Cyr, N. E., Earle, K., Tam, C., & Romero, L. M. (2007). The effect of chronic psychological stress on corticosterone, plasma metabolites, and immune responsiveness in European starlings. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 154(1-3), 59–66.

- Dinh, C.-M., & Park, S. (2022). How to increase consumer intention to use chatbots? An empirical analysis of hedonic and utilitarian motivations on social presence and the moderating effects of fear across generations. Electronic Commerce Research, 1–41.

- Almahri, F. A. J., Bell, D., & Merhi, M. (2020). Understanding student acceptance and use of chatbots in the United Kingdom universities: A structural equation modelling approach. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Management (ICIM), London, UK, 284–288.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 1, 39–50.

- García-Queiruga, M., Fernández-Oliveira, C., Mauríz-Montero, M. J., Porta-Sánchez, Á., Margusino-Framiñán, L., & Martín-Herranz, I. (2021). Development of the @Antidotos_bot chatbot tool for poisoning management. Farmacia Hospitalaria, 45(4), 180–183.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Go, E., & Sundar, S. S. (2019). Humanizing chatbots: The effects of visual, identity and conversational cues on humanness perceptions. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 304–316.

- Joshi, H. (2021). Perception and adoption of customer service chatbots among millennials: An empirical validation in the Indian context. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2021), 197-208.

- Hill, J., Ford, W. R., & Farreras, I. G. (2015). Real conversations with artificial intelligence: A comparison between human–human online conversations and human–chatbot conversations. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 245–250.

- Moon, J. K., Kim, E., Choi, S. M., & Sung, Y. (2013). Keep the social in social media: The role of social interaction in avatar-based virtual shopping. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 13, 14–26.

- Huang, M. H., & Rust, R. T. (2021). Engaged to a robot? The role of AI in service. Journal of Service Research, 24, 30–41.

- Kilteni, K., Groten, R., & Slater, M. (2012). The sense of embodiment in virtual reality. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 21, 373–387.

- Lakhal, S., Khechine, H., & Pascot, D. (2013). Student behavioural intentions to use desktop video conferencing in a distance course: Integration of autonomy to the UTAUT model. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 25, 93–121.

- Lee, K. M., & Nass, C. (2004). The multiple source effect and synthesized speech: Doubly disembodied language as a conceptual framework. Human Communication Research, 30(2), 182–207.

- Li, M., & Mao, J. (2015). Hedonic or utilitarian? Exploring the impact of communication style alignment on user’s perception of virtual health advisory services. International Journal of Information Management, 35(2), 229–243.

- McLean, G., & Osei-Frimpong, K. (2019). Hey Alexa… examine the variables influencing the use of artificial intelligent in-home voice assistants. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 28–37.

- Sugumar, M., & Chandra, S. (2021). Do I desire chatbots to be like humans? Exploring factors for adoption of chatbots for financial services. Journal of International Technology and Information Management, 30(3), 38–77.

- Mimoun, M. S. B., & Poncin, I. (2015). A valued agent: How ECAs affect website customers' satisfaction and behaviors. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 26, 70–82.

- Moore, G. C., & Benbasat, I. (1991). Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. Information Systems Research, 2(3), 192–222.

- Nguyen, T., Novak, R., Xiao, L., & Lee, J. (2021). Dataset distillation with infinitely wide convolutional networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34, 5186–5198.

- Paraskevi, G., & Saprikis, V. (2021). A literature review on users’ behavioral intention toward chatbots’ adoption. Applied Computing and Informatics, Emerald Publishing Limited.

- De Cicco, R., Silva Alparone, F. (2020). Millennials' attitude toward chatbots: An experimental study in a social relationship perspective. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 48(11), 1213–1233.

- Roy, R., & Naidoo, V. (2021). Enhancing chatbot effectiveness: The role of anthropomorphic conversational styles and time orientation. Journal of Business Research, 126, 23–34.

- Richad, V., Vivensius, S., Sfenrianto, & Kaburuan, E. R. (2019). Analysis of factors influencing millennial’s technology acceptance of chatbot in the banking industry Indonesia. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 10(4), 1270–1281.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford publications.

- Gaitán, J. A., Peral Peral, B., & Jerónimo, M. R. (2015). Elderly and internet banking: An application of UTAUT2. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, 20(1), 1–23.

- Abdul-Kader, S. A., & Woods, J. (2015). Survey on chatbot design techniques in speech conversation systems. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 6(7), 72–80.

- Sugumar, M., & Chandra, S. (2021). Do I desire chatbots to be like humans? Exploring factors for adoption of chatbots for financial services. Journal of International Technology and Information Management, 30(3), 38–77.

- Toader, D.-C., Boca, G., Toader, R., M?celaru, M., Toader, C., Ighian, D., & R?dulescu, A. T. (2020). The effect of social presence and chatbot errors on trust. Sustainability, 12(1), 256.

- Osuna, B., Karada?, E., & Orhan, S. (2015). The factors affecting acceptance and use of interactive whiteboard within the scope of FATIH project: A structural equation model based on the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. Computers and Education, 81, 169–178.

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478.

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178.

- Zhu, X., Li, R. Y. M., Crabbe, M. J. C., & Sukpascharoen, K. (2022). Can a chatbot enhance hazard awareness in the construction industry? Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 993700.

- Zumstein, D., & Hundertmark, S. (2017). Chatbots are coming – Opportunities and risks for online marketing. In Proceedings of the 17th Online Marketing Conference, Bern.

Received: 02-Jan-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-26-15594; Editor assigned: 06-Jan-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-26-15594(PQ); Reviewed: 20-Jan-2025, QC No. AMSJ-26-15594; Revised: 24-Feb-2026, Manuscript No. AMSJ-26-15594(R); Published: 03-Mar-2026