Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 5

Factors Contributing to Industrial Sickness in Small-Scale Enterprises: Empirical Evidence on Promoter Influence

Siva Krishna Golla, National Forensic Sciences University, Gandhinagar, Gujarat

Vengalarao Pachava, Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, Hyderabad

Surendar Gade, Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, Hyderabad

Citation Information: Krishna Golla, S., Pachava, V., & Gade S. (2023). Factors contributing to industrial sickness in smallscale enterprises: empirical evidence on promoter influence. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 27(5), 1-15.

Abstract

The Small-Scale Enterprise based industrial sickness and promoter’s behavior and proactive decision-making bears a relationship. The promoter’s behavior has been observed as instrumental in shaping the resolve for resilience and prevention of industrial sickness across small sector units. The rationale was to explore the role of promoter behavior and non-promoter aspects as shaping the industrial sickness in state perspective. The study seeks to explore the role of promoter’s age and promoter’s initial training in influencing the sickness affairs. The study seeks to examine the moderating role of promoter’s entrepreneurial orientation in influencing the outcomes. The structural equation modeling was leveraged to establish the moderating impact across 300 small scale entrepreneurs from across three select districts of Andhra Pradesh. The linkages hence were observed to support a host of hypothesis and assumptions that underline the prospects for recovery and revival of the aforesaid promoter run small businesses in state perspective.

Keywords

SSEs, Promoter Behavior, Industrial Sickness, Structural Equation Modeling.

Introduction

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SME) are seen to contribute significantly to the economy's short- and long-term growth prospects. The SME sector is made up of entrepreneurial units that take calculated risks and contribute to national and regional economy (Patil, 2011). The term small scale sector (Chandraiah, 2014) comprises the small-scale entrepreneurs who indulge in manufacture and production of the goods and services on the relatively smaller scale yet contribute significantly towards the national GDP, regional macroeconomic stabilization, employment generation, competitiveness in economy as well as development of ancillary support to the major industry and industrial developments in the region. The MSME ministry reported that in 2019-20 share of MSMEs was 36.9 per cent in terms of gross value added, 49.5 per cent in terms of products in total exports and 7.14 lakh in terms of employment generation.

Literature and approaches to Interpreting Industrial Sickness

Across the dominant academic literature, the “small business” or “small-scale unit” has been identified as more individual dominated or extensive focus on individual agency (Joshi, 2013). The person borne capabilities (Nadkarni, 2008) or deficiencies (Protogerou, 2008); do impact the outcomes and organizational survival. Indian context (Altenberg, 2011) of small-scale firms is characteristically different from global thinking as more family run enterprises with non-professional management is evident in Indian perspective. Individual sense-making (Belak, 2012) and leverage of competencies and resources, conventionally restricted access to markets and economic factors of production, constrained perceptions of state authorities, policy change by banking and credit institutions, and increased sensitivity to state and other contextually determined factors all have a greater impact on industrial economic health. The Indian perspective on small-scale firms seems to differ from global discourses in terms of stakeholders, the classification of possible causes, financial interpretation of assets and liabilities, and market orientation Table 1.

| Table 1 Interpreting The Small-Scale Industries And Industrial Sickness |

||

|---|---|---|

| Global Interpretation | Indian perspective | Andhra Pradesh based |

| Khelil and Smida: Observes the industrial sickness as an outcome of entrepreneur’s self-deception and biases in decision making (Khelill, 2016) Oogachi Framework: Regards the phenomenon as an outcome of owner’s articulation of corporate and business interest (Fernado, 2014) Resource dependency theory (Garicano, 2015) Contingency theory emphasizes the influences of social embeddedness and contextual actors Stakeholder approach |

Khandwalla’s approach towards organizational decline and turnaround (Khandwalla, 1981) Government based industrial policy interprets the sector and the units in terms of the investment caps as well as the contribution towards the economy BIFR approach (Manimala, 1991) Government based financial policy RBI perspective interprets the small-scale units as involving the investment proposition in terms of assets and liabilities. |

State based industrial policy State based financial policy |

Source: Compiled by author.

The literature (Khandwalla, 1981) identifies controllable aspect especially the internal factors as bearing a more imprint on industrial sickness than the external factors. The ‘internal factors’ classify as the controllable influences which have been observed as possessing maximum impact on operations, SME based ability to adjust and adapt to changing business environment, staying power deficiency as well as sustenance of business. The managerial or entrepreneur’s ability to take right decisions and conduct operations efficiently identify as prime contributor to organizational survival and ability to innovate. The illustration below brings together the factors as identified across literature. These factors are largely controllable yet contribute substantially towards the industrial or organizational decline Table 2.

|

||||||||||||

Source: Compiled by author.

Across the existing literature on subject matter (Cruzten, 2008), industrial sickness or corporate failure across SSI units has been a dominant phenomenon. A review of publications and citations across leading journals (Bretherton, 2005) reveal the incidence of gross instance of inability of the small sale units to conform itself with economic environment, non-ability to fit across changing economic and business circumstances as well as gross incompliance with regard to grow, sustain and survive. Despite the evident role of small-scale enterprises in supporting larger and mid-sized industrial ecosystems and manufacturing activity, the sector has been observed to sizzle under pressure and is reportedly facing more failures and sickness than ever before. Such a state of economy is not only evident across developing nations but also across developed economies of world.

Another perspective (Ahmad, 2009) on organizational sickness elaborates on the deterministic propositions involving the industry structure and input-output approach towards understanding the phenomenon of industrial sickness in small to medium sized enterprises. Another economic theory (Garicano, 2015) details the “industrial failure” as an outcome of two dimensions. The study across European firms (Garicano, 2015) concluded that organization become sick as they lack incentive-based support (managers, decision makers and stakeholders do not act in the manner that upholds organizational interests) or organizations succumb to rationality problems (decision makers, managers and employees do not possess the insights and knowledge, information and data with regard to acting in a rational manner).

The ‘non-controllable’ influences have been observed as emerging from the near neighborhood, the society or the business environment and categorize as non-controllable to a larger extent. The term controllable signifies the lack of management’s control over the functioning over other institutions, over other social and economic actors and industrial stakeholders. The illustration below captures some of the prominent non controllable influences from across business environment Table 3.

| Table 3 Non-Controllable Influences As Identified From Literature |

|

|---|---|

| Factor | Literary Support |

| Changes in current industry | (Conner, 1991), (Jennings, 1995), |

| Government policy-based turbulence | (Mehralizadeh, 2005), (Ahlstrom, 2004), (Muthu, 2015), (Zammel, 2016), (Manimala, 1991) |

| Access to factors of production | (Panigrahi, 2012), (Ooghe, 2006), (Shafique, 2013), (Spencer, 2003), (Pearce, 1993), (Siddiqui, 2018), (Cruzten, 2008) |

| Credit availability | (Rocha, n.d.), (Lee, 2016), (Thornhill, 2003), (Rizzo, 2012), (Datta, 2013), (Saparito, 2009) |

| Infrastructure connectivity | (Sharma, 2000), (Rocha, n.d.), (Gyampah, 2008) |

Source: Compiled by author.

Literature on Promoter’s Behavior

Internal factors such as managerial inefficiency, financial mismanagement, inconsistent and impermanent assessments of factors of production, technology-driven factors, and infrastructure-related factors have all been identified as contributing to firms' inability to operate effectively in turbulent environments. (Brown, 2012). Defects that are "internally located and determined" are usually regarded to have a greater role in establishing the pattern of strategy execution, business model implementation, as well as the overall use and allocation of elements of production within the unit concerned. (Dean, 2007). The implementation of the business model is significantly impacted by the prevalent internal inefficiencies.

The available research identifies internal inefficiencies at the unit level as incorporating the managerial or owner viewpoint, as well as planning, cognitive attitudes, and cognitive frameworks. (Gomez-Mejia, 1987) in terms of identifying and developing business opportunities in their most varied forms and contexts. The promoter’s perceptions of the environment and strategic decision making (Chaston, 1997) are vital as they laterally and directly decide and determine the scope and context of the sickness, business failure and the thrust for revival. The entrepreneur’s perceptions (Alom, 2016) with regard to the business-based decision making (Deshpande, 2004), marketing (Dragnic, 2014), product design (Fernado, 2014) and innovation (Merrilees, 2011). The promoter's perceptions of "self-assessed and determined" deficiencies or inefficiencies have long been believed to have a greater influence on the pattern of strategy execution, business model implementation, as well as the overall use and allocation of factors of production within the unit concerned (Dean, 2007).

The promoter’s attributes (locus of control, reasons for starting the current business, holistic capabilities, formal management education and prior exposure and experience with regard to operations management) do bear a relationship with the overall strategic management of the enterprises in times of recession and turbulence across the developing and low developing economies. The study across the South African small, micro and medical tourism enterprises established the cross-factor relationship across the strategy driving attributes of promoter’s locus of control, reasons for starting the current business, holistic capabilities, formal management education and prior exposure and experience with regard to operations management. Further the study observed the relationships across the attributes of South African small, micro and medical tourism enterprises (SMMTE) as influencing the overall enterprise based strategic behavior as a dependent variable. The behavioural biases in decision making (Yazdipour, 2010) and management heuristics (Atherton, 2003) are cognitive processes and mechanisms that influence decision making and sense making in relation to market dynamics and environmental uncertainty. The availability of asymmetrical information further complicates the small-scale unit's decision-making and its chances of survival or failure.

The existing literature with regard to managerial and entrepreneurial responses to uncertainty, asymmetrical information availability and prevalent business environment related turbulence; has often been reported to be biased as well as non-reflective of the best possible options that could have been exercised with regard to scarce resources and limited work force. A study (Atherton, 2003) highlighted the small business owner’s “knowledge-as–knowing” as involving the aspects of the non-uniformity, non-universality and complexity, dynamic as well as mixed in nature. Another research (Nimalathasan, 2008) on the relationship between owner knowledge of the environment and small-scale unit performance in Sri Lankan firms indicated the influence of formal strategic planning on unit-based functioning and economic performance. The manager began "strategic consistency" (Lamberg, 2009) in unit-based competition behaviour more than anything else. The succeeding occurrence may affect the unit's long-term viability, especially in small businesses.

The promoter's perceptions of strategic planning (Gibcus, 2009), external dependencies (Brown, 2012), and internal deficiencies (Cheng, 2015) matter in developing the promoter's awareness and understanding of the forces that shape and influence business planning and strategy execution in developing economies worldwide. Such promoter-based impressions cannot be quantified directly, but have been operationalized in prior research using entrepreneurs' self-assessments of their qualities (Chinomona, 2013), attitudes (Cheng, 2015), skill sets (Atherton, 2003), and inclinations (Nimalathasan, 2008). Such impressions in previous studies (Khelil, 2012) have been contextualised with owner beliefs, decisions, and attitudes. According to current research, the goal of such studies is to measure and quantify the links that lead to unit-based failure or decline due to the owner's attitude toward business planning and unit-based management.

The promoter’s perceptions of environment and the cognitive mapping in low velocity industries (Nadkarni, 2008) have been observed to be influential in shaping the strategy dynamics. It has been found that the promoter's planning and entrepreneurial mindset (Khelil, 2012) is a major distinction that distinguishes sick units from non-sick units.

It has been discovered that the promoter's passion, goals, and inclinations for entrepreneurial growth are what are responsible for revitalising and maintaining the company temperament, and therefore, the flow of revenues. The promoter’s self-driven inclination for entrepreneurial management of the entity amidst challenges from turbulent business environment seems to matter across the existing literature.

The promoter’s entrepreneurial orientation (Cruzten, 2008) has been interpreted as involving the aspects of the innovativeness in decision-making, risk-taking propositions, proactiveness in strategy execution as well as competitive aggressiveness (Dean, 2007). The lack of such an outlook (Chinomona, 2013) towards the unit could be evident in form of the delayed response of the unit towards the environment, changes in market demand and the respective loss of the timeliness of the enterprise’s response (Waktola, 2016).

The promoter’s own personality constitutes a major internally determined factor. The promoter’s personality attributes and orientations seem to impact the operationalization of the strategy and the planning for the venture. According to the findings of another study (Vani, 2017), the ability to take risks, the managerial skills, the technological literacy, the willingness to adopt new technology, the readiness to seek opportunity, the proficiency in managing public relations, and the ability to make decisions are all essential for the survival and sustenance of entrepreneurial endeavours.

A study (Malyadri, 2014) on the economic appraisal of entrepreneurship across small scale units in Andhra Pradesh found that factors like motivation, willingness to take risks, status, ability to innovate, rewards, and qualifications have a big effect on an entrepreneur's ability to keep going in a tough business environment. The study (Rao, 2014) and its outcomes pointed towards the incidence of the crucial role of the entrepreneurial forces in influencing the industry structure and the respective economic value creation in the economy in regional and national perspective. Another research study (Chowdhary, 2012) highlighted the evolving role (Vani, 2017) of entrepreneurial inclinations (Dess, 1983), orientations (Lakshmi, 2013), and motivations (Mishra, 2013) as shaping the individual's propensity (Malyadri, 2014) to engage in entrepreneurial activity (Sharma, 1985) and respective focus in small business perspective (Shetty, 1964). In different aspects, the regional studies have adequately highlighted the role of the entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intentions and orientations in shaping the regional stimulus for the micro level competitiveness of the small business enterprises in short- and long-term durations.

Existing studies (Rizzo, 2012) seem to highlight the evolving role of the local stimulus, individual promoters' entrepreneurial inclinations, and the promoter's passion, intentions, and inclinations for entrepreneurial growth. These factors have been observed as reviving and maintaining the business temperament and, as a result, the inflow of revenues. The promoter’s self-driven inclination for entrepreneurial management of the entity amidst challenges from turbulent business environment seems to matter for unit-based competitiveness development; across the existing literature.

The promoter’s entrepreneurial orientation (Dess, 1983) has been interpreted as involving the aspects of the innovativeness in decision-making, risk-taking propositions (Kessler, 2012), proactiveness in strategy execution as well as competitive aggressiveness (Dean, 2007). The lack of such an aggressive and competitive outlook towards the unit could be evident in form of the delayed response of the unit towards the environment, changes in market demand and the respective loss of the timeliness of the enterprise’s response (Waktola, 2016).

Objectives before Paper

The rationale was to explore the role of promoter behavior and non-promoter aspects as shaping the industrial sickness in state perspective. The study seeks to explore the role of promoter’s age and promoter’s initial training in influencing the sickness affairs. The study seeks to examine the moderating role of promoter’s entrepreneurial orientation in influencing the outcomes. Hence the proposed research hypothesis are:

H1: Promoter behavior is strongly related with sickness

H2: Perceptions of non-promoter aspects is strongly related with sickness

H3: The promoter’s ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ influences ‘promoter behavior’ and ‘perceptions of non-promoter aspects’ as well as outcomes in significant manner.

H4: The promoter’s ‘age’ influences ‘promoter behavior’ and ‘perceptions of non-promoter aspects’ as well as outcomes in significant manner.

H5: The promoter’s ‘training’ influences ‘promoter behavior’ and ‘perceptions of non-promoter aspects’ as well as outcomes in significant manner.

Methodology

In view of the research objectives and the hypothesis statements as well as the theoretical model as hypothesized in earlier stages, the research methodology was devised in a manner that facilitates the collection of the vital inputs from across the perceptions and opinions of the entrepreneurs spread across East Godavari, West Godavari and Krishna district of the state in focus. The research task was undertaken to gauge, to analyze and to classify the possible factors that shape and impact the current state of unit-based sickness or decline. Perceptions of the entrepreneurs were emphasised in order to ascertain the cross-factor relationships that ultimately result in the current state of failure or sickness among small businesses and small-scale industrial units in the Andhra Pradesh districts of East Godavari, West Godavari, and Krishna. The present research sample consists of units situated across three selected districts in Andhra Pradesh. These units, which are based on small businesses and are owned by entrepreneurs, would be subjected to study and interpretation. These units were found by looking at lists, publications, and handouts from the district industry commissioner's list of registered MSME and publications about "entrepreneur memorandums." Additionally, industrial units were identified via local industry groups and small unit or manufacturer associations. A list of 300 feasible and variably positioned promoters and varied sector-based units was identified using the lists obtained from various sources. The current research thus refers to sample frame as involving the small-scale units in East Godavari, West Godavari and Krishna district based industrial clusters that were accessible by road as well as identifiable by associations or similar registered name or entity. The sample frame comprises the registered small-scale unit that have executed and institutionalized the entrepreneur memoranda with MSME as nodal agency. The care was taken that the heterogeneity and representativeness of the sample is encouraged and sustained across the entire process of identification and analysis for research perspective. The judgmental sampling was undertaken to reach out to respondents across chosen districts Table 4.

| Table 4 Characteristics Of Respondents To This Study |

||

|---|---|---|

| District | Number of Respondents | Major Type |

| East Godavari | 100 | Rice Milling, Rice Oil based units |

| West Godavari | 100 | Packaging based units |

| Krishna | 100 | Agro based |

Source: Compiled by author.

Research Outcomes

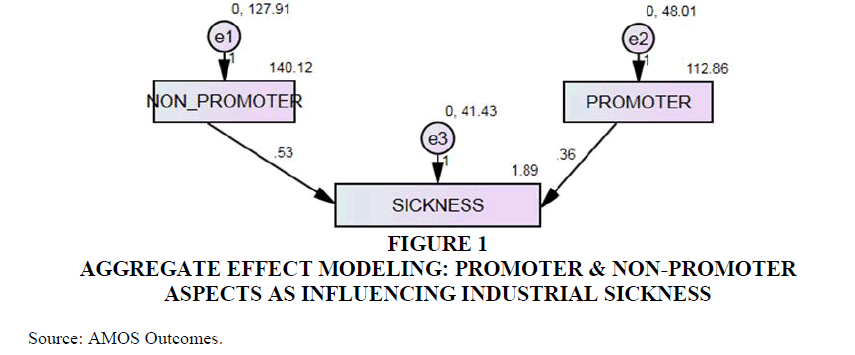

The structural relation between “promoter” aspects, “non-promoter” aspects and “unit-based sickness” were formally evaluated in a structural model as specified in the Figure 1. The promoter behavior and promoter’s perceptions of non-promoter aspects were observed as shaping unit-based sickness.

Figure 1: Aggregate Effect Modeling: Promoter & Non-Promoter Aspects As Influencing Industrial Sickness.

Source: AMOS Outcomes.

Where:

Promoter_Behavior = CU (Inadequate Capacity Utilization) + M (Inadequate Managerial control), +RP (Inappropriate Resource Planning+ O (Lack of Occupational Commitment) + EO=Lack of Entrepreneurial Orientation

Perceptions_NonPromoter= F (Factor Endowments), INF (Infrastructure Hassles)+ BCR(Bank credit availability)+PU(Policy Uncertainty) + CE(Changes in Economy)

Sickness=UBR= Unit’s bank relationship, MOF=Market orientation of firm, AME=Ability to meet expenses

The structural diagram above illustrates the impact of non-promoter factors and promoter driven factors on ‘industrial sicknesses. This upholds the assumption that industrial unit sickness is not uni-dimensional rather multi-dimensional and is contextual in nature Table 5.

| Table 5 Sickness and Relationships with Promoter and Non-Promoter-Driven Factors |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Relationships | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | ||

| H01 | SICKNESS | <--- | PROMOTER | .363 | .075 | 4.838 | *** |

| H02 | SICKNESS | <--- | NON_PROMOTER | .525 | .046 | 11.420 | *** |

Source: Compiled by author.

H01: Promoter behavior is strongly related with sickness

H02: Perceptions of non-promoter aspects is strongly related with sickness

The two hypothesis of this study argue that promoter and promoter’s perceptions of non-promoter factors would be positively related to industrial sickness probability.

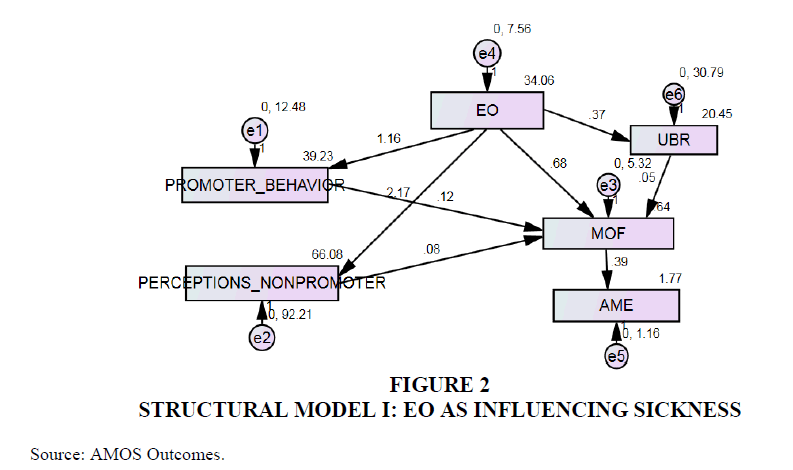

H03: The promoter’s ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ influences ‘promoter behavior’ and ‘perceptions of non-promoter aspects’ as well as outcomes in significant manner.

The hypothesis argues that promoter (entrepreneur) as an agency and his ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ significantly impacts behavior and sickness-based outcomes. The test for this hypothesis while controlling for ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ revealed two possible structural arrangements. The structural arrangements exhibited that ‘EO’ at aggregate level corresponded to impacts on ‘promoter behavior’ and ‘perceptions of non-promoter aspects’ as well as outcomes in significant manner. Thus, the hypothesis stands supported. This is equivalent to saying that EO influences ‘promoter behavior’, ‘perceptions of non-promoter aspects’ and ‘outcomes’ in myriad forms and aspects. The below mentioned structural models hence capture the two distinct patterns of influences Figure 2.

Structural Model I: EO as Influencing Sickness

Where: Promoter_Behavior = CU (Inadequate Capacity Utilization) + M (Inadequate Managerial control), +RP (Inappropriate Resource Planning+ O (Lack of Occupational Commitment) + EO (Lack of Entrepreneurial Orientation)

Perceptions_NonPromoter= F (Factor Endowments), INF (Infrastructure Hassles) + BCR (Bank credit availability) +PU (Policy Uncertainty) + CE (Changes in Economy)

UBR= Unit’s bank relationship, MOF=Market orientation of firm, AME=Ability to meet expenses

EO=Entrepreneurial Orientation Table 6.

| Table 6 Modeling the impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Label | ||

| PROMOTER_BEHAVIOR | <--- | EO | 1.162 | .104 | 11.189 | *** | par_3 |

| PERCEPTIONS_NONPROMOTER | <--- | EO | 2.173 | .281 | 7.726 | *** | par_4 |

| UBR | <--- | EO | .367 | .163 | 2.260 | .024 | par_7 |

| MOF | <--- | PROMOTER_BEHAVIOR | .124 | .053 | 2.360 | .018 | par_1 |

| MOF | <--- | PERCEPTIONS_NONPROMOTER | .085 | .019 | 4.370 | *** | par_2 |

| MOF | <--- | EO | .684 | .101 | 6.763 | *** | par_6 |

| MOF | <--- | UBR | .050 | .033 | 1.483 | .138 | par_8 |

| AME | <--- | MOF | .387 | .023 | 16.892 | *** | Par |

Source: AMOS Outcomes.

As evident, promoter and his ‘entrepreneurial orientation was observed to be affecting the general promoter behavior and perceptions of non-promoter aspects in decision making. The ‘entrepreneur’ as an ‘agency’ was observed as strongly shaping behaviors with model fit indices of RMSEA of 0.294 and CFI of 0.801. The promoter’s ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ was observed to lead to 1.162 times increase in ‘promoter behavior’ and 2.173 times increase in ‘Perceptions_NonPromoter’. Simply interpreted this is tantamount to saying that ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ is the primary factor or the attribute that shapes behavior and perceptions of promoter with regard to external aspects. In continuity the ‘promoter behavior’ aspect was observed to lead to 0.124 times increase in ‘market orientation’ and ‘Perceptions_NonPromoter’ aspect was observed to lead to 0.085 times increase in ‘market orientation Figure 3.

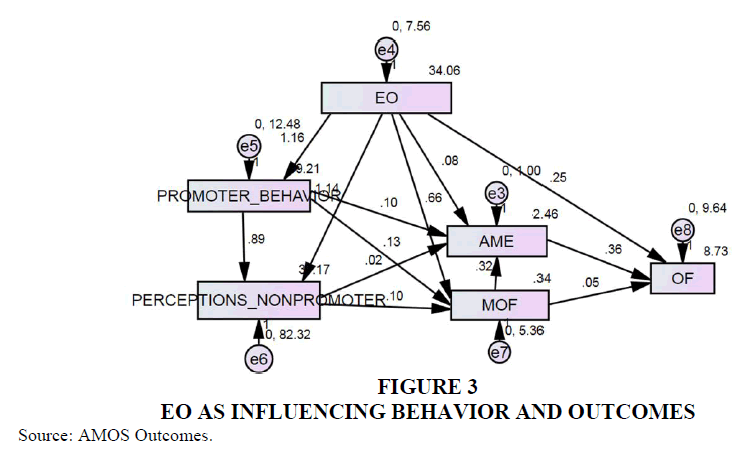

Structural Model II: EO as Influencing Behavior and Outcomes

As per alternative modeling of influences, promoter’s ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ was observed to lead to 1.162 times increase in ‘promoter behavior’ and 2.173 times increase in ‘Perceptions_NonPromoter’. In continuity the ‘promoter behavior’ aspect was observed to lead to 0.367 times increase in ‘market orientation’ and ‘Perceptions_NonPromoter’ aspect was observed to lead to 0.124 times increase in ‘market orientation’ Table 7.

| Table 7 Path Relationships |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Label | ||

| PROMOTER_BEHAVIOR | <--- | EO | 1.162 | .104 | 11.189 | *** | par_3 |

| PERCEPTIONS_NONPROMOTER | <--- | EO | 2.173 | .281 | 7.726 | *** | par_4 |

| UBR | <--- | EO | .367 | .163 | 2.260 | .024 | par_7 |

| MOF | <--- | PROMOTER_BEHAVIOR | .124 | .053 | 2.360 | .018 | par_1 |

| MOF | <--- | PERCEPTIONS_NONPROMOTER | .085 | .019 | 4.370 | *** | par_2 |

| MOF | <--- | EO | .684 | .101 | 6.763 | *** | par_6 |

| MOF | <--- | UBR | .050 | .033 | 1.483 | .138 | par_8 |

| AME | <--- | MOF | .387 | .023 | 16.892 | *** | par_5 |

Source: AMOS Outcomes.

These two versions of promoter’s ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ point towards prevalence of two distinct patterns of aggregate effects of ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ on respective ‘promoter behavior’ and ‘perceptions of non-promoter aspects.

These two types of structural models and resultant modeling of influences is essential to capture the effect that ‘entrepreneurial orientation’ can exert across controllable and non-controllable aspects vis a vis sickness. In similar aspect, the role of promoter’s age was explored in shaping the research outcomes.

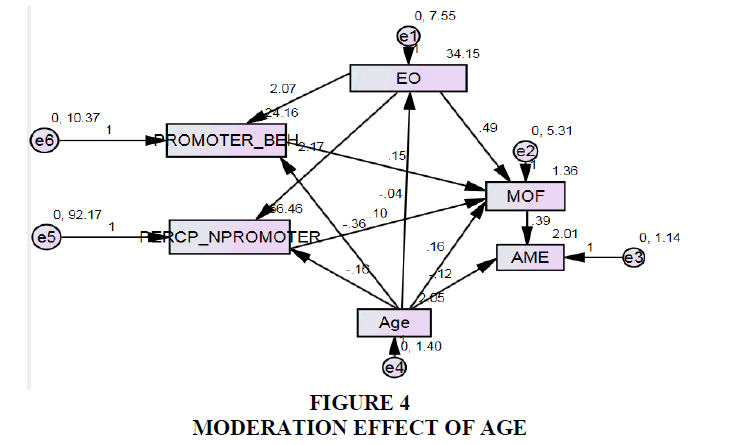

H04: The promoter’s ‘age’ influences ‘promoter behavior’ and ‘perceptions of non-promoter aspects’ as well as outcomes in significant manner Figure 4.

The model reported a NFI of 0.931, RFI of 0.639, IFI of 0.937, CFI of 0.935 Table 8.

| Table 8 Moderation Effect Of Age |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Label | ||

| EO | <--- | Age | -.044 | .187 | -.233 | .816 | par_11 |

| PROMOTER_BEH | <--- | EO | 2.074 | .094 | 21.984 | *** | par_1 |

| PERCP_NPROMOTER | <--- | EO | 2.172 | .281 | 7.723 | *** | par_2 |

| PERCP_NPROMOTER | <--- | Age | -.163 | .654 | -.249 | .803 | par_7 |

| PROMOTER_BEH | <--- | Age | -.364 | .219 | -1.661 | .097 | par_8 |

| MOF | <--- | EO | .487 | .143 | 3.395 | *** | par_3 |

| MOF | <--- | PERCP_NPROMOTER | .103 | .019 | 5.324 | *** | par_5 |

| MOF | <--- | PROMOTER_BEH | .155 | .058 | 2.688 | .007 | par_6 |

| MOF | <--- | Age | .156 | .158 | .988 | .323 | par_9 |

| AME | <--- | MOF | .388 | .022 | 17.243 | *** | par_4 |

| AME | <--- | Age | -.123 | .073 | -1.700 | .089 | par_10 |

In similar aspect, the role of promoter’s training was explored in shaping the research outcomes.

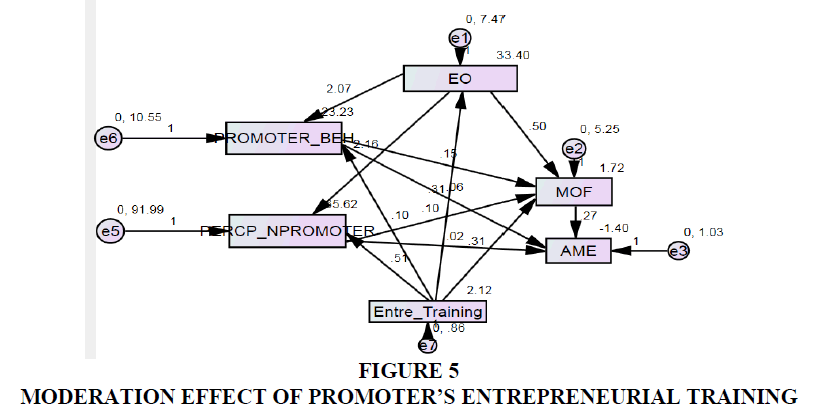

| Table 9 Moderation Effect Of Promoter’s Entrepreneurial Training |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Label | ||

| EO | <--- | Entre_Training | 0.312 | 0.237 | 1.319 | 0.187 | par_11 |

| PROMOTER_BEH | <--- | EO | 2.074 | 0.096 | 21.675 | *** | par_1 |

| PERCP_NPROMOTER | <--- | EO | 2.155 | 0.283 | 7.628 | *** | par_2 |

| PERCP_NPROMOTER | <--- | Entre_Training | 0.513 | 0.836 | 0.614 | 0.539 | par_9 |

| PROMOTER_BEH | <--- | Entre_Training | 0.096 | 0.283 | 0.339 | 0.735 | par_10 |

| MOF | <--- | EO | 0.496 | 0.142 | 3.49 | *** | par_3 |

| MOF | <--- | PERCP_NPROMOTER | 0.102 | 0.019 | 5.293 | *** | par_5 |

| MOF | <--- | PROMOTER_BEH | 0.146 | 0.057 | 2.564 | 0.01 | par_6 |

| MOF | <--- | Entre_Training | 0.315 | 0.2 | 1.574 | 0.116 | par_12 |

| AME | <--- | MOF | 0.273 | 0.034 | 7.998 | *** | par_4 |

| AME | <--- | PERCP_NPROMOTER | 0.018 | 0.009 | 1.971 | 0.049 | par_7 |

| AME | <--- | PROMOTER_BEH | 0.064 | 0.018 | 3.654 | *** | par_8 |

The model reported a NFI of 0.951, RFI of 0.659, IFI of 0.956, CFI of 0.954.

H05: The promoter’s ‘training’ influences ‘promoter behavior’ and ‘perceptions of non-promoter aspects’ as well as outcomes in significant manner Figure 5.

Conclusion

The research achieved the modeling of the causal impact across the constituent factors that were supposed to aid or contribute towards the state of sickness or revival across the small-scale enterprises or small businesses in East Godavari, West Godavari and Krishna districts of the state of Andhra Pradesh. The linkages hence were observed to support a host of hypothesis and assumptions that underline the prospects for recovery and revival of the aforesaid promoter run small businesses in state perspective.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Author contributions: All contributions are those of the author.

Funding: There is no funding for this research.

Conflict of interest: I, the corresponding author, declare that there are no conflicts of interest on behalf of all authors.

References

Agle, M. (1999). Who matters to CEOs? An investigation of Stakeholder Attributes and Salience,Corporate Performance and CEO Values . Academy of Management Journal.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ahlstrom, B. (2004). Guest Editor's introduction to special issue. Turnaround in Asia: Laying the foundation for understanding this unique domain . Asia Pacific Journal of Management.

Ahmad. (2009). Dissecting behaviours associated with business failure: A study of SME owners in Malayasia and Australia . Asian Social Science.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alom, A. (2016). Success factors of overall improvement of microenterprises in Malaysia: An empirical study on the contexts . Journal of global entrepreneurship research.

Altenberg. (2011). Industrial Policy in developing countires . Working Paper.

Ambrosini, B. (2009). Dynamic Capabilities: An exploration of how firms renew their resource base . British Journal of Management, 20.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Arasti, Z., Zandi, F., & Bahmani, N. (2014). Business failure factors in Iranian SMEs: Do successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs have different viewpoints?. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 4, 1-14..

Atherton, A. (2003). The uncertainty of knowing: An analysis of the nature of knowledge in a small business context.Human Relations,56(11), 1379-1398.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bamfo, A. (2015). Planning in Small Businesses: The perspectives of Owners Managers . International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management.

Belak, D. (2012). Integral management: key success factors in the MER model. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica,9(3), 5-26.

Bretherton, C. (2005). Resource dependency and SME strategy: an empirical study.Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development,12(2), 274-289.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bridoux, F. (2004). A resource-based approach to performance and competition: An overview of the connections between resources and competition .Luvain, Belgium Institut et de Gestion, Universite Catholique de Louvain,2(1), 1-21.

Brown, K. (2012). The effect of internal control deficiencies on the usefulness of earnings in executive compensation .Advances in Accounting,28(1), 75-87..

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Calvo, G. (2010). Established business owner's success: Influencing factors. Journal of Development Entrepreneurship, 15(03), 263-286

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chandraiah, V. (2014). The prospects and problems of MSMEs sector in India : An analytical study . International Journal of Business and Management Invention.

Chaston. (1997). Small firm performance: assessing the interaction between entrepreneurial style and organizational structure .European journal of Marketing,31(11/12), 814-831.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cheng, G. (2015). Internal control and operational efficiency .(2015). InEuropean Accounting Association Annual Congress(pp. 28-30).

Chinomona. (2013). Business owner’s expertise, employee skills training and business performance: A small business perspective .Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR),29(6), 1883-1896.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chittithaworn, I. (2011). Factors affecting business success of small & medium enterprises (SMEs) in Thailand. Asian social science,7(5), 180-190.

Chowdhary. (2012). Empirical study on reasons of industrial sickness-with reference to Jammu & Kashmir Industries Ltd. IOSR Journal of Business and Management,5(5), 48-55.

Conner. (1991). A historical comparison of resource-based theory and five schools of thought within industrial organization economics: do we have a new theory of the firm? .Journal of management,17(1), 121-154.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Crutzen, C. (2010). The origins of small business failure: A grounded typology. The Origins of Small Business Failure: A Grounded Typology . In9ème Journée d'Etude sur les Faillites.

Cruzten, C. (2008). The business failure process: an integrative model of the literature .Review of Business and Economics,53(3), 287-316.

Dai, I. (2010). Entrepreneurial optimism, credit availability, and cost of financing: Evidence from US small businesses. Journal of Corporate Finance,44, 289-307.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Datta. (2013). Industrial sickness in India–An empirical analysis .IIMB Management Review,25(2), 104-114.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dean, M. (2007). Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action .Journal of business venturing,22(1), 50-76.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Deshpande, F. (2004). Organizational culture, market orientation, innovativeness, and firm performance: an international research odyssey .International Journal of research in Marketing,21(1), 3-22.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dess. (1983). Consensus in the Strategy Formulation Process and Firm Performance. InAcademy of Management Proceedings(Vol. 1983, No. 1, pp. 22-26). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dragnic. (2014). Impact of internal and external factors on the performance of fast-growing small and medium businesses .Management-Journal of Contemporary Management Issues,19(1), 119-159.

Fernado. (2014). Entrepreneurial competencies and business failure .International journal of Entrepreneurship,18, 1.

Fernando, S. (2017). Are competencies and corporate strategy aligned? An exploratory study in Brazilian steel mills .Revista Ibero Americana de Estratégia,16(4), 117-132.

Garicano, R. (2015). Why organizations fail: Models and cases .Journal of Economic Literature,54(1), 137-192.

Gibcus, V. (2009). Strategic decision making in small firms: a taxonomy of small business owners. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business,7(1), 74-91.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gomez-Mejia, T. (1987). Managerial control, performance, and executive compensation .Academy of Management journal,30(1), 51-70.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gyampah, A. (2008). Manufacturing strategy, competitive strategy and firm performance: An empirical study in a developing economy environment .International journal of production economics,111(2), 575-592.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jennings, B. (1995). The managerial dimension of small business failure .Strategic Change,4(4), 185-200.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Joshi. (2013). Critical success factors of micro & small enterprises in Ethiopia: A Review .International Journal of Science and Research,5(10), 1056-1060.

Kessler, K. (2012). Predicting founding success and new venture survival: A longitudinal nascent entrepreneurship approach .Journal of Enterprising Culture,20(01), 25-55.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Khandwalla. (1981). Strategy for turning around complex sick organizations .Vikalpa,6(3-4), 143-166.

Khelil, S. (2012). Understanding the Failure of New Companies: A Qualitative Multi-dimensional Exploration .Review of Entrepreneurship, 11, 39-72.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lahtinen, T. H. (2011). Resource usage decisions and business success: a case study of Finnish large-and medium-sized sawmills .Journal of Forest Products Business Research,6(3), 1-18.

Lakshmi. (2013). The Performance of Small-scale Industries in India .Market Survey.

Lamberg. (2009). Competitive dynamics, strategic consistency, and organizational survival .Strategic Management Journal,30(1), 45-60.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, Y. (2016). Analysis of industrial structure, firm conduct and performance–A case study of the textile industry .Autex Research Journal,16(2), 35-42.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Malyadri. (2014). An Economic Appraisal of Entrepreneurship in Small Scale Industries - A Study on Nellore District. International Journal of Emerging Research in Management & Technology, 3(2): 64-81.

Manimala. (1991). Turnaround management: Lessons from successful cases . ASCI Journal of Management, 20(4), 234-39.

Mehralizadeh, S. (2005). A study of factors related to successful and failure of entrepreneurs of small industrial business with emphasis on their level of education and training .Available at SSRN 902045.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Merrilees, T. (2011). Marketing capabilities: Antecedents and implications for B2B SME performance. Industrial Marketing Management,40(3), 368-375.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mishra. (2013). A big synergy,proven success required to settle closure of SMEs . International Journal of Business Management and Research, 3(2).

Muthu. (2015). Sickness in Micro,Small and Medium enterprises(MSMEs) in India . International journal of interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary studies.

Nadkarni, B. (2008). Environmental context, managerial cognition, and strategic action: An integrated view .Strategic management journal,29(13), 1395-1427.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Natarajan. (1985). Rehabilitation of Sick Units in SSI Sector through Marketing-Strategy A Case Study'. Indian Journal of Marketing,15(7), 13-16.

Neill. (1986). An analysis of the turnaround strategy in commercial banking .Journal of Management Studies,23(2), 165-188.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nimalathasan. (2008). A study of owner-manager’s environmental awareness and small business performance. Manager, (07), 83-88.

Ooghe, P. (2006). Failure processes and causes of company bankruptcy: a typology .Management decision,46(2), 223-242.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pacheco. (2015). SMEs probability of default: The case of the hospitality sector .Tourism & Management Studies,11(1), 153-159.

Panigrahi. (2012). Risk Management in Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) in India: A Critical Appraisal .Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Management Review,1(4).

Patil. (2011). Role of small scale Industries in economic development .Research Gate..

Pearce, R. (1993). Toward improved theory and research on business turnaround .Journal of management,19(3), 613-636.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pearson, C. (2001). Perceived societal values of Indian managers: Some empirical evidence of responses to economic reform .International Journal of Social Economics.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Protogerou, C. (2008). Dynamic capabilities and their indirect impact on firm performance (No. 08-11).DRUID, Copenhagen Business School, Department of Industrial Economics and Strategy/Aalborg University, Department of Business Studies.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rao, A. (2014). A Study of Entrepreneurial Success in Small Scale Enterprises in Chittoor District of Andhra Pradesh .International Journal of Management and Development Studies,3(7), 01-09.

Raymond, P. (2010). Strategic capabilities for the growth of manufacturing SMEs: A configurational perspective. Journal of developmental entrepreneurship,15(02), 123-142.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rizzo, F. (2012). Understanding small business strategy: A grounded theory study on small firms in the EU State of Malta .Journal of Enterprising Culture,20(03), 287-332.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rocha, E. A. G. (2012).The impact of the business environment on the size of the micro, small and medium enterprise sector; preliminary findings from a cross-country comparison .Procedia Economics and Finance,4, 335-349.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Runyan, H. (2007). A resource based view of the small firm: Using qualitative approach to uncover small firm resources . Qualitative Market Resarch: An International Journal, 10(4).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Saparito. (2009). Perceptions of bank-firm relationship: does gender similarity matter?. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research,29(1), 2.

Shafique, R. (2013). Determinants of entrepreneurial success/failure from SMEs perspective .IOSR Journal of Business and Management,1, 83-92.

Sharma. (1985). Industrial Sickness in India: An Analysis. ASCI Journal of Management,15(1), 15-18.

Sharma. (2000). Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate choice of environmental strategy .Academy of Management journal,43(4), 681-697.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shetty. (1964). Entrepreneurship in small industry .The Economic Weekly,6, 917-920.

Siddiqui. (2018). Problems and Challenges of Indian MSMEs in the Post Demonetization Era .Vol. XXIV Issue I.

Spencer, G. (2003). The relationship among national institutional structures, economic factors, and domestic entrepreneurial activity: a multicountry study .Journal of business research,57(10), 1098-1107.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Thornhill, A. (2003). Learning about failure: Bankruptcy, firm age, and the resource-based view .Organization science,14(5), 497-509.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vani. (2017). Study on the attitudes of Micro,Small and Medium entrepreneurs in the SPSR Nellore District . International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews, 4(3),166-173

Vijande, S. (2012). How organizational learning affects a firm's flexibility, competitive strategy, and performance .Journal of business research,65(8), 1079-1089.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Waktola, H. (2016). Analysis of the Main Cause for the Entrepreneurs Drop Out in Micro and Small Enterprises: Evidences from Nekemte Town, Eastern Wollega Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia .Int J Econ Manag Sci,5(376), 2.

Yazdipour, C. (2010). Predicting firm failure: A behavioral finance perspective .The Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance,14(3), 90-104.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zammel, K. (2016). The Causes of Tunisian SME Failure .Arabian J Bus Manag Review,6(274), 2.

Received: 03-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13417; Editor assigned: 04-Apr-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-13417(PQ); Reviewed: 28-May-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-13417; Revised: 20-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13417(R); Published: 08-Jul-2023