Research Article: 2026 Vol: 30 Issue: 1

From Self-Leadership to Sales Success: A Serial Mediation of Proactive Behavior and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Bidisha Banerjee, Zayed University, Dubai

Saswat Barpanda, Goa Institute Of Management, India

Citation Information: Barpanda, S., & Banerjee, B. (2025). From self-leadership to sales success: a serial mediation of proactive behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 30(1), 1-18.

Abstract

This research paper investigates the interplay between self-leadership, sales performance, proactive behavior, and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Drawing upon existing literature in organizational psychology and sales management, the study employs a serial mediation model to explore the sequential impact of self-leadership on sales performance through the mediating roles of proactive behavior and OCB. A theoretical serial mediation model was developed to examine the proposed relationship. The hypotheses were tested using regression analysis with bootstrapping. In total, 120 sales professionals participated in this study.The findings reveal a significant positive association between self-leadership and sales performance, providing empirical support for the notion that individuals who exhibit higher levels of self-leadership are likely to achieve superior sales outcomes. Further analysis uncovers the serial mediating effects of proactive behavior and OCB in this relationship. Proactive behavior is identified as an intermediate mechanism through which self-leadership positively influences sales performance, emphasizing the importance of initiative-taking and anticipatory actions in the sales domain. Moreover, organizational citizenship behavior is also established as an additional independent mediator, underscoring the role of discretionary, extra-role behavior in enhancing sales performance. The research contributes to the existing literature by elucidating the sequential nature of these mediating mechanisms, shedding light on the nuanced pathways through which self-leadership influences sales outcomes. Practical implications for sales management and organizational development are discussed, offering insights for fostering self-leadership, proactive behavior, and OCB to optimize sales team performance. The findings of this study contribute to a deeper understanding of the psychological and behavioural dynamics that drive sales success, providing a foundation for future research and managerial interventions in the field of sales leadership and performance.

Keywords

Self leadership, Proactive Behaviour, Sales Performance, Organization Citizenship behaviour, Serial mediation

Introduction

Leadership plays a vital role in Sales Organization, which helps to maximize efficiency and achieve organizational goals. In general, leadership is defined as influencing others and achieving common goals of the organization (Ingram, 2005). According to (Ganta & Manukonda's, 2014) research, leadership represents a form of authority through which an individual can shape or transform the values, beliefs, behaviours, and attitudes of another person. Sales performance is a critical aspect of organizational success, and understanding the factors that contribute to high sales performance is essential for businesses aiming to thrive in a competitive market. One intriguing area of research that has gained prominence is the relationship between self-leadership and sales performance, particularly through the lens of proactive behavior. This discussion delves into the research output exploring how self-leadership influences sales performance by fostering proactive behavior among sales professionals (Ingram et al., 2005).

Within this ever-changing sales environment, many companies have undertaken a new initiative to bolster the leadership capabilities of their employees. (Furtner, 2017; Fewings & Henjewele, 2019) emphasizes the importance of self-leadership in empowering overall leadership. Moreover, leaders are the central person who makes a difference more than anything else (Browing,2018). On a contrasting note, self-leadership fosters a deep understanding of one's identity, capabilities, and direction. This self-awareness is coupled with the capacity to influence communication, emotions, and behaviors while striving to achieve set goals. Nevertheless, a leader's effectiveness plays a pivotal role in guiding employees to improve their skills and behaviors, enabling them to become proficient self-leaders (Lynch & Corbett, 2021; Stewart et al., 2019).

As per the works of (Neck et al., 1999; Neck & Houghton, 2006), self-leadership is described as a self-influence process that empowers individuals to cultivate their own self-direction and self-motivation. This quality is of utmost importance for CEOs, managers, business owners, and a wide array of professionals in authoritative positions. The achievements of prominent leaders in their respective domains are often attributed to their personal discipline and execution. The foundation of effective self-leadership lies in self-determination, self-regulation, and social-cognitive theories (Furtner & Baldegger, 2016; Tang et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2020).

Numerous studies have demonstrated the significant impact of self-leadership on performance, as exemplified by Mantra (1998). Despite previous research in organizational behavior and its associated limitations, this paper delves into the direct and indirect influence of self-leadership on sales performance through various variables within the sales context.

Theoretical Background And Hypotheses Development

Self-determination theory (SDT) by Deci & Ryan, 1985) suggests that individuals have intrinsic motivation and a need for autonomy. In the lens of SDT self-efficacy plays a significant role in shaping the effectiveness of self-leadership strategies on performance. Elevated self-efficacy has a direct impact on an individual's level of effort and persistence, resulting in enhanced overall performance. Extensive research underscores the positive correlation between high self-efficacy and improved performance (Räsänen,2017). Self-leadership can be seen as a way to enhance intrinsic motivation and autonomy, leading to proactive behavior and OCB, which can positively influence sales performance. Further as per the Job Characteristics Model (Hackman & Oldham, 1976), certain job characteristics, such as autonomy and variety, can influence employee motivation and performance. It identifies five core job characteristics: skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback. These characteristics influence employees' psychological states, which in turn impact their outcomes such as motivation and job satisfaction. Self-leadership can be seen as a means to create job characteristics that promote critical psychological states like proactive behavior and OCB, ultimately leading to outcomes in the form of improved sales performance. Also, in the lens of Social cognitive theory (Bandura,1999) which embraces diverse viewpoints on adaptation, human development, and transformation, Social cognitive behavior depicts individuals’ behavior about how they equip themselves to face changes and challenges, and as an enabler of self-leadership development resulting in enhanced employee performance (Ayub & Kokkalis, 2017).

Self-leadership and Sales Performance

Self-leadership is a process through which individuals influence themselves to achieve self-directed and self-motivated work needed to behave in a desirable way (Houghton et al., 2003). Self-leadership strategies are rooted in self-regulation, self-control, and self-management theories and have been divided further into three categories, i.e., behavioral–focused strategies, natural reward strategies, and constructive thought pattern strategies (Houghton et al., 2003). The implementation of these three strategies aids individuals in becoming more self-directed and self-motivated in their work, ultimately boosting their performance (Manz, 1986; Marthaningtyas, 2016).

Self-leadership strategies help people build pleasant features into their activities so that the task becomes naturally rewarding (Manz & Neck 2004) and enhances their performance. Such strategy increases individual intrinsic motivation, self-determination, and feeling of competence (Deci & Ryan 1985, Neck & Houghton, 2006). When a person gets more status, power, and intrinsic motivation to fulfill their job, the work becomes more rewarding, and performance increases (Herzberg et al 2003).

In recent years, researchers have suggested that self-leadership focuses on self-awareness rules that inspire a person to perform at their best (Cranmer, Goldman & Houghton, 2019). An individual who exhibits self-leadership behavior is more likely to improve his or her performance (Neck & Houghton 2006; Sahin, 2011; Faruk, 2011). Despite previous research efforts, there remains a significant gap in our understanding of how self-leadership directly impacts performance within the sales context. To address this gap, our study aims to explore the direct influence of self-leadership on sales performance.

Self-leadership makes an individual more self-motivated and self-directed in their work by taking their responsibilities and decisions to fulfill their goal. On the other hand, it also helps in self-analysis, improvement of belief systems, and positive self-talk to improve their performance.

Thus, we can state H1 as follows

H1: Self Leadership has a direct and positive influence on performance.

Self-Leadership, Proactive Behavior and Sales Performance

Individuals who manage themselves employ self-leadership strategies promoting behavioral awareness and intention, generating intrinsic task motivation, and having constructive thoughts (Houghton et al.,2012). Those who effectively lead themselves can plan and improve their work and situations, anticipate future outcomes, and increase intrinsic motivation to effect change (Hauschildt & Konradt, 2012). (Neck & Houghton, 2006) introduced a framework outlining three key strategies within the concept of self-leadership: Behavior-focused strategies: These strategies are geared towards enhancing self-awareness and facilitating self-management, particularly when dealing with tasks that may be less desirable. Natural reward strategies: This approach seeks to create situations in which individuals are intrinsically motivated and rewarded for their assigned activities and tasks. Constructive thought pattern strategies: This strategy revolves around the processes through which individuals can steer their thoughts in directions that are conducive to their goals and objectives. The importance of cultivating and maintaining positive, productive thinking was also emphasized (Neck et al.,2020). (Crant, 2000) introduced the concept of self-starting as a valuable personal resource and a fundamental aspect of proactive behavior, showcasing an individual's capacity to manage themselves proactively. Self-leadership significantly influences work performance by empowering individuals to proactively manage themselves and stay motivated. This proactive approach enables individuals to anticipate future conditions and adapt to evolving job roles, as highlighted by (Grant & Ashford, 2008).

By employing self-leading strategies, individuals can effectively plan and enhance their productivity. For instance, cognitive strategies, such as mental imagery, enable individuals to envision positive future outcomes, fostering proactive behavior. Natural rewards, which boost intrinsic motivation, inspire individuals to improve their work environments, further enhancing their performance. Additionally, behavior-oriented strategies, including goal-setting and self-recognition, enable individuals to engage in proactive planning, as noted by (Hauschildt & Konradt, 2012). These strategies collectively contribute to individuals' proactive behavior and, consequently, their overall work performance. As of our current knowledge, there appears to be a scarcity of research investigating the link between self-leadership and work-life balance. While (Cranmer et al., 2019) revealed that self-leadership impacts an employee's proactivity, and (Marques-Quinteiro & Curral, 2012) identified that self-enhancement strategies have a direct influence on proactive work performance, mediating the relationship between proactive work role performance and overall work performance (Browning, 2018).

These concepts and the related studies suggest that self-empowerment may have a positive correlation with work-life balance. However, it's worth noting that previous research has primarily focused on the connection to overall Proactive Work Behavior (PWB).

This study aims to fill this gap in the literature by providing evidence that demonstrates the relationship between self-efficacy and Proactive Work Behavior, shedding light on how self-leadership may influence an individual's work-life balance.

Proactive Behaviour and Sales Performance

In a rapidly changing dynamic environment, proactive behavior is crucial for Organizational success (Crant, 2000; Frese & Fray, 2001). Proactive individuals take self-directed action to anticipate or initiate change in their sales performance or work roles (Grant & Ashford, 2008; Husniati & Pangestuti, 2018). Proactive behavior is crucial, from idea generation to idea implementation (Rank et al., 2004; Sukmayanti et al., 2018), which is an integral part of sales. Researches has also shown that Proactive behaviour as a social behaviour intends to explore and explain how project managers’ proactive behaviour could be enhanced in a project by the use of integrated collaborative environments (Kapogiannis et al., 2021). The dynamic approach to successful project management emphasizes the continual improvement of a project manager's abilities, allowing them to exercise control and make well-informed decisions (Kerzner, 1999; Morris et al, 2006; Fewing et al., 2019). Enhancing these skills is crucial to improving their overall performance. Despite numerous studies in the field, there remains a scarcity of research conducted within the specific context of sales.

In general, when an employee is proactive in their work will reflect on his performance level. Hence, Proactive behaviour influences to Sales performance and also mediates to Sales performance.

Thus, we can state H2 as follows

H2a: Self Leadership has a direct and positive influence on proactive Behaviour.

H2b: Proactive Behaviour has a positive influence to Sales Performance

H2c: Proactive Behaviour mediates Self-Leadership on Sales Performance

Self-Leadership, Organizational Citizenship Behaviour and sales performance

Organizational citizenship behavior is the conduct of an employee who is motivated more by volunteerism than by the needs of his job (Rioux & Penner, 2001; Nonnis et al., 2020). According to (Lestari & Ghaby, 2018), organizational citizenship behavior is a habit or behavior that is practiced willingly and is not associated with a specific position. Employees who exhibit strong organizational citizenship will be more successful and productive (Triyanthi & Subudi, 2018). Organizational citizenship behavior is personal conduct that is undertaken voluntarily; it has no direct impact on accomplishment. To boost performance, individuals must also contribute to the company's efficacy. Productivity will rise when the workgroup has a strong foundation.

Self-leadership is a multifaceted concept that involves a combination of cognitive and behavioral processes aimed at guiding and regulating one's actions to achieve desired outcomes. (Putra & Sintaasih, 2018; Rasanen, 2017) characterize self-leadership as the understanding of self-influence, which serves as a driving force for individuals to proactively engage in tasks that inherently motivate them. Furthermore, self-leadership can be viewed as a conscious effort to guide oneself in performing tasks that may not be inherently desirable but are necessary.

Drawing upon insights from multiple experts in the field, it can be distilled that Self-Leadership, is a process through which individuals influence themselves and take proactive actions to self-motivate, ultimately working towards the attainment of their desired goals.

H3a: Self-leadership has a positive influence to Organizational Citizenship Behaviour

H3b: Organizational Citizenship Behaviour Influence Sales Performance

H3c Organizational Citizenship Behaviour mediates the influence of Self-leadership on Sales Performance

Proactive Behavior and OCB

(Belschak & Hartog, 2010). Established a relationship between proactive behaviour and OCB. A studied by (Srivastava & Pathak, 2019) Proactive behaviour involves taking charge of an activity, acting in advance of a future situation, rather than reacting, and initiating change. This proactive and self-initiating perspective to work makes employees go beyond the formal call of a job and engage in OCB. Further Using social exchange theory, (Idzna, Raharjo & Afrianty, 2021) to determine the effect of organizational support (POS) and proactive personality on commitment and OCB.

H4: Proactive Behaviour influence the OCB

The Serial Mediating Role of Proactive Behaviour and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour on Self-Leadership and Sales Performance

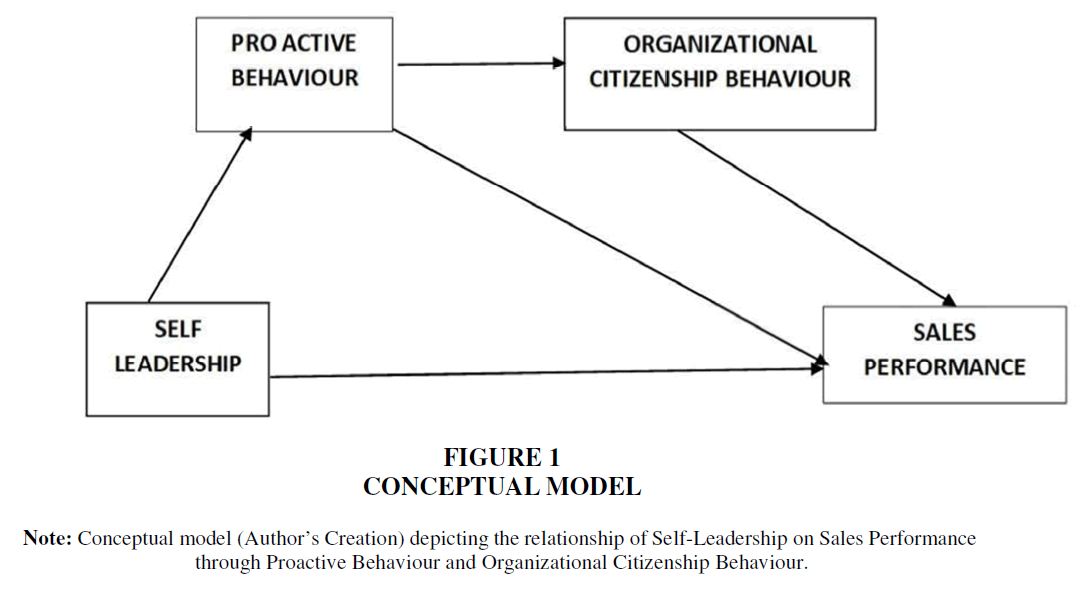

In the framework of Social Learning Theory, employees have the capacity to shape and cultivate their proactive behavior through a process of learning, gaining experience, and being influenced by others. This can lead to the enhancement of their self-leadership skills, as they observe, and adapt their behavior and strategies from their social work environments to become more proactive and effective in their roles. Several researchers have stated that self-starting is an important aspect of proactive behavior (Crant, 2000), which helps the individual to be self-motivated and self-directed and affects Organizational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB) (Lopez-Dominguez et al., 2013) and Proactive behavior (Ohly & Fritz, 2007). As an essential organizational agent, Self-Leadership proactively transforms their values to their employees (Jung & Avolio, 1999). Similarly, (Zhang & Ciu, 2022) suggests that Self-Leadership proactive behavior influences OCBs who seek to envision the future, show a positive attitude to their work, and adapt to change (Erkutlu & Ben Chafra, 2016) Figure 1.

Thus, we can state H5 as follows.

H5: Proactive Behaviour and OCB play a serial mediation between Self-Leadership and Sales Performance

Research Methodology

Sample and Data Collection Procedure

A survey method was employed with a structured questionnaire to validate the proposed theoretical model and to empirically test the research hypotheses. The data was collected from registered diverse industries under the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, India such as Pharmaceuticals, Information Technology, Banking, Insurance, Automobiles, Consumer Durables, FMCG, and Media from three major cities of India (Delhi, Kolkata, and Bangalore). According to (Morgan et al., 2004), this multi-industry sample was used to increase the observed variance and to reinforce the generalization of the findings of the current study.

Table 1 depicts the sector wise participants of the present study along with the number of companies’ participation. Maximum participation in this study belongs to the pharmaceuticals industry with (42.5 %) followed by insurance sector (12.5%) and banking sector (almost 11%) respectively. It is fact that response rate from automobile and logistics industry also good. However, a total of nine industries are considered in this study.

| Table 1 Sector-Wise Companies and Number of Respondents | ||

| Sector Industries | N | % |

| Pharmaceuticals | 51 | 42.5 |

| Information Technology | 7 | 5.83 |

| Banking | 13 | 10.83 |

| Insurance | 15 | 12.5 |

| Automobiles | 12 | 10 |

| Consumer Durable | 5 | 4.17 |

| FMCG | 2 | 1.67 |

| Media | 4 | 3.33 |

| Logistics | 11 | 9.17 |

| Total | 120 | 100 |

The distribution of the research instrument was done in different proportions with the help of managers or representatives of the respective companies. A total of 250 pairs of questionnaires were distributed using a multistage sampling technique. In each pair, two different sets of questionnaires were sent: one for the salesperson and one for the supervisor. In the end, only 120 pairs of completed questionnaires were received from 9 different sectors. Based on the information provided by the participants, a code was assigned to one of them to ensure their anonymity, non-biasedness, and proper identification of the respondents. To encourage their participation, a report with the results of the research was promised. Table 1 provides a summary of the data collection procedure.

Measures

Self-Leadership

Self-Leadership was measured with 20 items based on the measure developed by (Manz, 1992). Likewise, we utilize this measure to assess the self-leadership of the salesperson. This scale measures to which people employ the three different types of self-leadership the behavioral-focused strategies, Natural reward strategies, Constructive thought pattern strategies). Employees were asked to indicate the extent to which they used this leadership on a seven-point scale ranging from 1) Disagrees 7) completely agrees.

Organizational Citizenship behavior

Organizational Citizenship Behaviour was assessed by the employees with 14 items developed by (Podsakoff & Mac Kenzie, 1993). Items are enlisted in the table. Responses of this items were made on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1) Strongly Disagree 7) Completely agree.

Proactivity

Proactivity was assessed by the employees with a 5-item developed by (Bateman & Crant, 1993). Items are enlisted in a table. Responses of these items were made on 7-point scale ranging from 1) Strongly Disagree 7) Completely agree.

Sales Performance

Sales Performance was assessed by the employees with 6 items developed by (Behrman & Perreault, 1982). Items are enlisted in the table. Responses to these items were made on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1) strongly disagree to 7) strongly agree.

Analysis and Interpretation

Three separate methodological approaches were required to examine the research questions. The first goal was to confirm the reliability and the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement constructs, to ensure that the items consistently measured the constructs they were intended to measure (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was run independently for each item. The second part of the analysis involved running Structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the theoretical model. All the analysis was performed using the statistical package AMOS 21 and PROCESS macro Version 4.2.

The survey instruments with the descriptive statistics are presented in the Appendix. It shows each item’s mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis. In terms of standard deviation, there was a range from .98 to 1.65. Skewness (≤|1.29|) and kurtosis (≤|2.73|) results showed that none of the items were greater than (>) the recommended cut-off points of |3.00| and |8.00|, respectively, and there was no univariate non-normality present (Kline, 1998; Kline, 2023). The variance inflation factor values were 1.18–1.85, the tolerance values were .53–.84 (which is above .25), and the Durbin Watson value was 1.43, which indicates that there was no multicollinearity and residual problem (Field, 2017). Correlations, and reliabilities for the study variables are displayed in Table – and -. As expected, sales performance is positively associated with proactive behavior (r = .69, p < .01), OCB (r = .71, p < .01), and self-leadership (r = .60, p < .01). The inter-factor correlations of self-leadership which consists of Behaviourally Focussed (SaL), Constructive thought pattern strategies (CpS), and natural rewards (NaR) is more than .70 with p<.01. OCB also positively correlated ((r = .48, p < .01) with proactive behavior.

Firstly, the analysis here confirms that all items load substantially and significantly on their respective constructs confirming the existence of convergent validity (Table 2). Even the discriminant validity is also statistically significant here in the model shown in Table 2 and Table 3. CFA was also performed to analyze dimensionality and goodness of fit of the Second Order for Self-Leadership and First Order for other constructs i.e. proactive behavior, OCB, and Sales Performance (Table 2 & Table 3). All fit indicators obtained guarantee a good fit of the scales: RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), and GFI (Goodness of Fit Index) (Bentler & Bonett, 1980). The RMSEA is one of the most informative criteria for evaluating model fit. A RMSEA value lower than 0.08 is reasonable (Byrne, 2001). CFI, and GFI values higher than 0.9 indicate acceptable fit (Byrne, 2001). As Table 3 shows, all values obtained through CFA for all constructs are within the range regarded as sufficient in the literature Table 4.

| Table 2 Convergent and Discriminant Validity Values | |||||||||

| CR | AVE | MaxR(H) | SaPerf | ProA | ORCBE | NaR | CpS | SeL | |

| SaPerf | 0.912 | 0.634 | 0.923 | 1 | |||||

| ProA | 0.8 | 0.506 | 0.827 | .697** | 1 | ||||

| ORCBE | 0.918 | 0.618 | 0.925 | .710** | .478** | 1 | |||

| NaR | 0.919 | 0.656 | 0.923 | .627** | .712** | .400** | 1 | ||

| CpS | 0.915 | 0.573 | 0.916 | .589** | .730** | .324** | .788** | 1 | |

| SeL | 0.881 | 0.554 | 0.885 | .605** | .698** | .375** | .953** | .818** | 1 |

| Table 3 Measures Properties of Confirmatory Factor Analysis | |||

| Measures | Code | Factor Loading | Cronbach Alpha |

| Self-Leadership | |||

| Behavioural focused | SeL | ||

| I think about my progress in my job. | SL1 | 0.79 | 0.87 |

| I make a point to keep track of how I'm doing. | SL2 | 0.69 | |

| I pay attention to how well I'm doing. | SL3 | 0.8 | |

| I consciously have goals in my mind. | SL4 | 0.7 | |

| I keep a record of progress in my tasks. | SL5 | 0.73 | |

| I pay attention to what I'm telling myself. | SL6 | 0.73 | |

| Natural Reward | NaR | ||

| I try to extend my area of responsibility. | SL7 | 0.82 | 0.91 |

| I focus on ways I can extend my responsibility. | SL8 | 0.82 | |

| I think about new responsibilities I can take over. | SL9 | 0.8 | |

| I try to do more than my assigned responsibilities. | SL10 | 0.85 | |

| I think about increasing my responsibilities. | SL11 | 0.83 | |

| I look for activities beyond my responsibilities. | SL12 | 0.71 | |

| Constructive thought pattern strategies (CpS) | CpS | ||

| I take action to solve problems on my own. | SL13 | 0.75 | 0.91 |

| I like to act to solve problems by myself. | SL14 | 0.7 | |

| If I have a problem, I solve it myself. | SL15 | 0.74 | |

| I identify solutions to problems in my mind. | SL16 | 0.79 | |

| I think through solutions to problems on my own. | SL17 | 0.76 | |

| I think up ways to solve problems. | SL18 | 0.78 | |

| I choose to make improvements in how I do my job. | SL19 | 0.75 | |

| I try to think of positive changes I can make in my job. | SL20 | 0.75 | |

| Proactive behaviour | |||

| I enjoy facing and overcoming obstacles to my ideas. | Pro1 | 0.81 | 0.8 |

| I excel at identifying opportunities. | Pro3 | 0.55 | |

| I love to challenge the status quo. | Pro4 | 0.63 | |

| I can spot a good opportunity long before others can. | Pro5 | 0.79 | |

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior | ORCBE | ||

| He is willing to take time out of his busy Schedule to help with recruiting or training new agents. | OCB1 | 0.65 | 0.91 |

| He ‘Touches base’ with other before initiating actions that might affect them. | OCB2 | 0.808 | |

| He takes steps to prevent problems with other agents and or other personnel of the company. | OCB3 | 0.746 | |

| He encourages other agents when they are down. | OCB4 | 0.796 | |

| He acts as a ‘’peacemaker’’ when other in the agency have disagreements. | OCB5 | 0.811 | |

| He is a stabilizing influence in the agency when dissention occurs. | OCB6 | 0.818 | |

| He attends functions that are not required but help the company image. | OCB7 | 0.857 | |

| Sales Performance | SaPerf | ||

| He makes presentations of actual sales of both current clients and the future. | SP2 | 0.86 | 0.9 |

| He achieves the annual sales objectives and other established objectives. | SP3 | 0.71 | |

| He understands the needs of the client and the process of working | SP5 | 0.72 | |

| He helps to improve the performance of the unit of sales. | SP6 | 0.79 | |

| He provides feedback to your supervisor. | SP7 | 0.76 | |

| He helps to increase the market share in its territory. | SP8 | 0.89 | |

| Table 4 CFA for All Variables | ||||

| CFA model | PCMIN/df | CFI | GFI | RMSEA |

| Self-leadership | 1.33 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.046 |

| Proactive Behavior | 1.43 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.065 |

| OCB | 1.48 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.043 |

| Sales Performance | 1.31 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.051 |

Causal Effects

(Hayes, 2013) SPSS macro PROCESS (Model 6) with a 95 % bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) based on 10, 000 bootstrap samples was used to examine the total, direct, and indirect effects of self-leadership on sales performance through proactive behavior and organization citizenship behavior. The indirect effect is considered statistically significant if the CI does not contain zero Tanle 4.

The direct effect of Self-leadership on sales performance (β=.36), and proactive behavior (β=.68) is significant whereas is non-significant with OCB (β=.13). Sales Performance is also significantly influenced by OCB (β=.68). However, influence of proactive Behaviour on OCB is significant (β=.17) whereas its influence on sales performance (β=.17) is insignificant

Mediation Analysis

Process macro is considered to be a highly effective program for testing serial mediation models (Hayes, 2013). The advantage of this analytical approach put forward by (Hayes, 2013) is that it allows the mediator variables assumed to have a priority to be modelled in such a way to influence the subsequent variables. In addition, serial mediation models allow testing the mediator variables in theoretical order (Vartanian et al., 2016) Serial mediation assumes “a chain linking the mediators, with a specified direction of causal flow” (Hayes, 2012). In brief, mediator variables between dependent and independent variables can be serially tested in serial mediation models (Hayes, 2018). Furthermore, (Hayes & Scharkow, 2013) procedure directly tests, with the help of the bootstrapping method, the significance of the indirect effect generated by the independent variable on the dependent variable through mediator variables. Obtaining bootstrapped confidence intervals for specific indirect effects could be problematic in the majority of SEM programs. For example, although the AMOS program provides bootstrapped confidence intervals for overall indirect effects, it is not possible to obtain bootstrapped confidence intervals for specific indirect effects (Leth-Steensen & Gallitto, 2016). Therefore, in the current study, the PROCESS macro is considered to be a better option for hypothesis testing, unlike the parallel mediating models which claim that no mediator variable causally affects the other Table 5.

| Table 5 Direct and Indirect Effects of Self-Leadership on Sales Performance | ||||||

| Causal Relationship | β | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Hypotheses | Accepted /Rejected |

| Direct Effect | ||||||

| Self-Leadership → Sales Performance |

.36 | .095 | .358 | .667 | 1 *** | Accepted |

| Self-Leadership → Proactive Behaviour |

.68 | .071 | .546 | .828 | 2a *** | Accepted |

| Proactive Behaviour → Sales Performance |

.17 | .071 | -.004 | .357 | 2b (NS) | Rejected |

| Self-Leadership → OCB | .13 | .08 | -.029 | .295 | 3a (NS) | Rejected |

| OCB → Sales Performance | .687 | .10 | .481 | .894 | 3b *** | Accepted |

| Proactive Behaviour → OCB | .17 | .07 | .016 | .329 | 4** | Accepted |

| Indirect Effects | ||||||

| Mediation Relationship | β | Boot SE |

Boot LLCI |

Boot ULCI |

Hypotheses | Accepted /Rejected |

| Self-Leadership → Proactive Behaviour → Sales Performance |

.121 | .076 | .037 | .265 | 2c | Accepted |

| Self-Leadership → OCB → Sales Performance |

.091 | .054 | .004 | .211 | 3c | Accepted |

| Self-Leadership → Proactive Behaviour → OCB → Sales Performance |

.082 | .039 | .009 | .165 | 5 | Accepted |

Direct and indirect effects of Self-Leadership on Sales Performance.

The serial mediation simultaneously tested three mediation pathways describes the effects of the paths linking self-leadership to each mediator and sales performance. All indirect paths from self-leadership to sales performance show significantly positive outcomes. Self-LeadershipàProactive Behaviourà Sales Performance quality (β=.121; CI=.037,.265), Self-Leadershipà OCBà Sales Performance (β=.091; CI=.004,.211), and serial mediation paths of Self-LeadershipàProactive Behaviourà OCBàSales Performance (β=.082; CI=.009,165). Serial mediation analyses showed Proactive behavior and OCB mediate the association between Self-leadership and sales performance. The total indirect effect of Self-leadership on sales performance through Proactive behavior and OCB and the combination of Proactive behavior and OCB accounted for the overall model was 55%, which indicates that mediation effects of Proactive behavior and OCB play important roles in the association between Self-leadership and sales performance

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis of serial mediation analysis is shown in Appendix 2. The opposing direction effects of proactive behavior and OCB on the association between self-leadership and sales performance were presented in the sensitivity analysis (Self-leadership → Proactive Behaviour → Self Leadership). The variable of OCB was included as the first mediator, while proactive behavior was considered as the second mediator. According to the sensitivity analysis, we found that proactive behavior, as the second mediator, did not mediate the association between sleep quality and life satisfaction nor there is a significant serial mediation of OCB and Proactive behavior observed.

Discussion

The relationship we have explored involving self-leadership, proactive behavior, organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), and sales performance can be understood through the lens of the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) by Albert Bandura (2001). SCT emphasizes the role of observational learning, imitation, and modeling in the development of behavior. Thus, in this context, self-leadership can be seen as a component of self-regulation and self-efficacy, which are key elements in SCT. Individuals who practice self-leadership are likely to be more effective in setting and achieving their goals. Proactive behavior can be viewed as a manifestation of self-efficacy, where individuals believe in their ability to influence their environment. SCT suggests that observing others being proactive can influence an individual to engage in similar behavior. Research suggests that self-leadership plays a crucial role in shaping proactive behavior among sales professionals. Sales, being a dynamic and competitive field, demands individuals who can adapt to challenges, take initiative, and seize opportunities. Self-leadership empowers sales professionals with the skills and mindset necessary to exhibit proactive behavior in their roles. Further, OCB can be linked to the social aspects of SCT. Individuals who engage in OCB may be influenced by observing positive behavior in their social context. Bandura's emphasis on social modeling and the impact of role models aligns with the idea that OCB can be learned through observation and social interactions. Higher self-efficacy may lead to increased organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) – discretionary actions that benefit the organization beyond one's formal job requirements. Individuals with leadership skills can believe in their ability to influence their environment which creates discretionary behavior in employees that go beyond formal job requirements, contributing to the overall effectiveness of the organization and impacts performance outcomes. In summary, Social Cognitive Theory provides a framework that encompasses self-efficacy, observational learning, and self-regulation, making it relevant to understanding the relationship between self-leadership, Proactive behavior, OCB and sales performance. Teams observing self-leadership and proactive behavior within their members are likely to develop a culture that supports these behavior. This, in turn, can positively impact overall team performance, including sales outcomes. Organizations can reinforce OCB by recognizing and rewarding employees who engage in such behavior. Social reinforcement, in the form of positive feedback, promotions, or other incentives, can be linked to both self-leadership and OCB, encouraging employees to continue and expand their positive contributions.

As par job characteristic model, self-leadership is likely related to autonomy, as it involves individuals taking initiative, setting goals, and regulating their own behavior (Inam et.al., 2023). Autonomy, a key component of JCM, can contribute to the development of proactive behavior. When individuals have the freedom to make decisions and take initiative, they are more likely to engage in proactive actions. This in turn creates OCB which involves behavior that goes beyond employees' formal job requirements for the benefit of the organization. Sales performance, perhaps facilitated by self-leadership practices, could be explored as a mechanism for improving and sustaining high levels of performance.

Theoretical Implication

The theoretical implications and contributions of the research are multifaceted and significant. Firstly, the study contributes to the broader understanding of self-leadership as a critical factor in the sales domain. This supports the work of Kalra et al. (2021). It underscores that empowering sales professionals with self-leadership skills can be instrumental in enhancing their adaptability to challenges. This insight extends existing theories on leadership by emphasizing the role of internal motivation, self-regulation, and self-influence in driving positive outcomes within the sales context. Secondly, the research sheds light on the mechanism through which self-leadership influences sales performance – by fostering proactive behavior. Proactivity, in this context, emerges as a key mediator between self-leadership and sales outcomes. This finding enriches our comprehension of the intricate interplay between individual psychological processes and observable performance metrics in the sales profession. Moreover, the study introduces a novel perspective by examining the link between self-leadership and OCB in the sales context. The identification of a positive association implies that cultivating self-leadership not only enhances formal job-related tasks but also encourages sales professionals to engage in discretionary, positive behavior that contribute to the overall well-being of the organization. This contributes to organizational behavior literature by demonstrating the ripple effect of self-leadership on behavior that go beyond the contractual obligations of employees.

Managerial/Practical Implications: Practical Implications

Understanding the relationship between self-leadership, proactive behavior, and OCB in the context of sales performance has practical implications for both individuals and organizations.

Organizations can design training programs that focus on developing self-leadership skills among their sales teams. These programs may include modules on self-awareness, goal setting, and techniques for maintaining high levels of self-motivation. Sales leaders can play a pivotal role in fostering a self-leadership culture within their teams. By providing support, encouragement, and resources, leaders can empower sales professionals to take ownership of their roles and exhibit proactive behavior. When hiring for sales positions, organizations may consider assessing candidates' self-leadership qualities. Individuals with a strong self-leadership orientation are likely to bring a proactive mindset to their sales roles, contributing to better overall performance.

Practically, the research suggests that organizations aiming to improve sales performance should invest in developing self-leadership skills among their sales force. Training programs, coaching, and interventions designed to enhance self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-motivation can serve as effective strategies for fostering self-leadership within the sales team. Such initiatives may result in a more adaptive, proactive, and organizationally supportive sales force, ultimately driving positive sales outcomes.

Limitations and Future Scope

The study was conducted with a sample of 120 sales professionals, which might limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader population of sales professionals with different demographics, industries, or organizational structures. While the study proposes a serial mediation model with proactive behavior and OCB as sequential mediators, there might be other unexplored variables influencing the relationship between self-leadership and sales performance. Future research could consider additional mediators or moderators to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms. Despite the theoretical framework suggesting a sequential relationship, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to make definitive causal inferences. Experimental or quasi-experimental designs could be employed in future research to establish causality more firmly.

Investigate potential moderating factors that may influence the strength or direction of the relationships identified in the study. Factors such as organizational culture, leadership styles, or individual differences could be explored to provide a more nuanced understanding. Conduct comparative studies across different industries or organizational contexts to assess the generalizability of the findings. Understanding how these relationships vary in diverse settings could contribute to the practical applicability of the research. Finally, Combining quantitative findings with qualitative insights to provide a richer understanding of the psychological and behavioural dynamics in the sales domain. Qualitative data could offer context and depth to the quantitative results obtained.

By addressing these limitations and exploring the suggested avenues for future research, scholars can further advance the understanding of the complex interplay between self-leadership, proactive behavior, OCB, and sales performance, providing valuable insights for both academia and practitioners in the field of sales leadership and performance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the research output examining the relationship between self-leadership and sales performance through proactive behavior and OCB highlights the significance of individual empowerment in the sales domain. By cultivating self-leadership skills, sales professionals can become proactive contributors to their organizations, adapting to challenges, cultivating positive discretionary behavior in employees that goes beyond formal job requirements, and driving positive sales outcomes. As businesses continue to recognize the importance of human capital in achieving competitive advantages, understanding and leveraging the dynamics of self-leadership in the sales context becomes increasingly vital. This research not only advances our theoretical understanding of the intricate dynamics between self-leadership, proactive behavior, OCB, and sales performance but also provides practical insights for organizations seeking to empower their sales professionals and enhance overall sales effectiveness.

Appendix 1

| Measures | |||||

| Self-Leadership | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| Behavioural focused SeL | |||||

| I think about my progress in my job. | SL1 | 5.76 | 1.33 | -1.01 | 0.24 |

| I make a point to keep track of how I'm doing. | SL2 | 5.59 | 1.33 | -0.81 | -0.08 |

| I pay attention to how well I'm doing. | SL3 | 5.83 | 1.07 | -0.8 | -0.14 |

| I consciously have goals in my mind. | SL4 | 6 | 0.98 | -0.85 | 0.23 |

| I keep a record of progress in my tasks. | SL5 | 5.73 | 1.18 | -0.79 | 0.01 |

| I pay attention to what I'm telling myself. | SL6 | 5.84 | 1.09 | -1.29 | 2.65 |

| Natural Reward NaR | |||||

| I try to extend my area of responsibility. | SL7 | 5.62 | 1.27 | -1.16 | 1.41 |

| I focus on ways I can extend my responsibility. | SL8 | 5.64 | 1.15 | -1.17 | 2.73 |

| I think about new responsibilities I can take over. | SL9 | 5.5 | 1.37 | -0.84 | 0.24 |

| I try to do more than my assigned responsibilities. | SL10 | 5.67 | 1.39 | -1.12 | 0.92 |

| I think about increasing my responsibilities. | SL11 | 5.52 | 1.27 | -0.92 | 1 |

| I look for activities beyond my responsibilities. | SL12 | 5.43 | 1.52 | -0.76 | -0.46 |

| Constructive thought pattern strategies (CpS) | |||||

| I take action to solve problems on my own. | SL13 | 5.71 | 1.21 | -1.09 | 1.65 |

| I like to act to solve problems by myself. | SL14 | 5.74 | 1.18 | -0.93 | 1.03 |

| If I have a problem, I solve it myself. | SL15 | 5.76 | 1.3 | -1.18 | 1.55 |

| I identify solutions to problems in my mind. | SL16 | 5.81 | 1.17 | -0.91 | 0.96 |

| I think through solutions to problems on my own. | SL17 | 5.6 | 1.2 | -0.88 | 1.74 |

| I think up ways to solve problems. | SL18 | 5.77 | 1.24 | -1.15 | 1.52 |

| I choose to make improvements in how I do my job. | SL19 | 5.73 | 1.23 | -1.03 | 0.6 |

| I try to think of positive changes I can make in my job. | SL20 | 5.83 | 1.26 | -0.89 | -0.13 |

| Proactive behaviour | |||||

| I enjoy facing and overcoming obstacles to my ideas. | Pro1 | 5.5 | 1.38 | -0.88 | 0.15 |

| I excel at identifying opportunities. | Pro3 | 5.65 | 1.01 | -0.56 | -0.24 |

| I love to challenge the status quo. | Pro4 | 5.53 | 1.22 | -0.78 | 0.37 |

| I can spot a good opportunity long before others can. | Pro5 | 5.45 | 1.37 | -0.89 | 0.47 |

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior | ORCBE | ||||

| He is willing to take time out of his busy Schedule to help with recruiting or training new agents. | OCB1 | 5.38 | 1.2 | -0.7 | 0.94 |

| He ‘Touches base’ with other before initiating actions that might affect them. | OCB2 | 4.55 | 1.63 | -0.43 | -0.86 |

| He takes steps to prevent problems with other agents and or other personnel of the company. | OCB3 | 4.67 | 1.48 | -0.18 | -0.78 |

| He encourages other agents when they are down. | OCB4 | 5 | 1.57 | -0.96 | -0.01 |

| He acts as a ‘’peacemaker’’ when other in the agency have disagreements. | OCB5 | 4.88 | 1.65 | -0.74 | -0.33 |

| He is a stabilizing influence in the agency when dissention occurs. | OCB6 | 4.95 | 1.33 | -0.33 | 0.06 |

| He attends functions that are not required but help the company image. | OCB7 | 4.75 | 1.37 | -0.32 | -0.39 |

| Sales Performance SP2,3,5,6,7,8 | |||||

| He makes presentations of actual sales of both current clients and the future. | SP2 | 5.24 | 1.36 | -0.75 | 0.13 |

| He achieves the annual sales objectives and other established objectives. | SP3 | 5.39 | 1.15 | -0.34 | -0.41 |

| He understands the needs of the client and the process of working | SP5 | 5.51 | 1.06 | -0.58 | -0.02 |

| He helps to improve the performance of the unit of sales. | SP6 | 5.29 | 1.23 | -0.7 | 0.27 |

| He provides feedback to your supervisor. | SP7 | 5.24 | 1.51 | -0.65 | -0.57 |

| He helps to increase the market share in | SP8 | 5.34 | 1.34 | -0.56 | -0.45 |

| its territory. | |||||

Appendix 2

| Sensitivity Analysis of Indirect Effects | ||||

| Effect | ß | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| Self-Leadership → Proactive Behaviour → Sales Performance | .121 | .076 | .037 | .265 |

| Self-Leadership → OCB → Sales Performance | .091 | .054 | .004 | .211 |

| Self-Leadership → OCB → Proactive Behaviour → Sales Performance | .0081 | .0086 | -.0034 | 0299 |

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ayub, A., & Kokkalis, P. (2017). Institutionalization and social cognitive behavior resulting in self-leadership development: A framework for enhancing employee performance in corporate sector in Pakistan. International Journal of Business and Society, 18(S3), 617–640.

Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of personality. In Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 154–196).

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1993). The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(2), 103–118.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Behrman, D. N., & Perreault, W. D., Jr. (1982). Measuring the performance of industrial salespersons. Journal of Business Research, 10(3), 355–370.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Belschak, F. D., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2010). Pro-self, prosocial, and pro-organizational foci of proactive behaviour: Differential antecedents and consequences. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2), 475–498.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Browning, M. (2018). Self-leadership: Why it matters. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 9(2), 14–18.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling: Perspectives on the present and the future. International Journal of Testing, 1(3–4), 327–334.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cranmer, G. A., Goldman, Z. W., & Houghton, J. D. (2019). I’ll do it myself: Self-leadership, proactivity, and socialization. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(6), 684–698.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 435–462.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Erkutlu, H., & Ben Chafra, J. (2016). Value congruence and commitment to change in healthcare organizations. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 13, 316–333.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fewings, P., & Henjewele, C. (2019). Construction project management: An integrated approach. Routledge.

Field, A. (2017). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS (5th ed.).

Frese, M., & Fay, D. (2001). Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23, 133–187.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Furtner, M. (2017). Self-leadership. Springer Gabler.

Furtner, M., & Baldegger, U. (2016). Self-leadership und Führung: Theorien, Modelle und praktische Umsetzung (2nd ed.). Gabler.

Ganta, V. C., & Manukonda, J. K. (2014). Leadership during change and uncertainty in organizations. International Journal of Organizational Behaviour & Management Perspectives, 3(3), 1183.

Grant, A. M., & Ashford, S. J. (2008). The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 3–34.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hauschildt, K., & Konradt, U. (2012). Self-leadership and team members' work role performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(5), 497–517.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hauschildt, K., & Konradt, U. (2012). The effect of self-leadership on work role performance in teams. Leadership, 8(2), 145–168.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling (White paper).

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Houghton, J. D., Neck, C. P., & Manz, C. C. (2003). Self-leadership and superleadership. In Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership (pp. 123–140).

Houghton, J. D., Wu, J., Godwin, J. L., Neck, C. P., & Manz, C. C. (2012). Effective stress management: A model of emotional intelligence, self-leadership, and student stress coping. Journal of Management Education, 36(2), 220–238.

Husniati, R., & Pangestuti, D. C. (2018). Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) in UPN “Veteran” Jakarta employees. Journal of Indonesian Community Service, 1(1).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Idzna, A., Raharjo, K., & Afrianty, T. W. (2021). The influence of perceived organizational support and proactive personality on organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. In AICoBPA 2020 (pp. 97–101).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Inam, A., Ho, J. A., Sheikh, A. A., Shafqat, M., & Najam, U. (2023). How self-leadership enhances normative commitment and work performance. Current Psychology, 42(5), 3596–3609.

Ingram, A. (2005). Global leadership and global health: Contending meta-narratives, divergent responses, fatal consequences. International Relations, 19(4), 381–402.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ingram, T. N., LaForge, R. W., Locander, W. B., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2005). New directions in sales leadership research. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 25(2), 137–154.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jung, D. I., & Avolio, B. J. (2000). Opening the black box: The mediating effects of trust and value congruence. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(8), 949–964.

Kapogiannis, G., Fernando, T., & Alkhard, A. M. (2021). Impact of proactive behaviour antecedents on construction project managers’ performance. Construction Innovation, 21(4), 708–722.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford.

Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford.

Lestari, E. R., & Ghaby, N. K. F. (2018). Pengaruh organizational citizenship behavior terhadap kepuasan kerja dan kinerja karyawan. Industria: Jurnal Teknologi dan Manajemen Agroindustri, 7(2), 116–123.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Leth-Steensen, C., & Gallitto, E. (2016). Testing mediation in structural equation modeling. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(2), 339–351.

López-Domínguez, M., Enache, M., Sallan, J. M., & Simó, P. (2013). Transformational leadership as an antecedent of change-oriented OCB. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 2147–2152.

Lynch, M. P., & Corbett, A. C. (2021). Entrepreneurial mindset shift and the role of cycles of learning. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–22.

Manz, C. C. (1986). Self-leadership: Toward an expanded theory. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 585–600.

Manz, C. C. (1992). Self-leadership: The heart of empowerment. The Journal for Quality and Participation, 15(4), 80.

Manz, C. C., & Neck, C. P. (2004). Mastering self-leadership: Empowering yourself for personal excellence.Pearson.

Marques-Quinteiro, P., & Curral, L. A. (2012). Goal orientation and work role performance. The Journal of Psychology, 146(6), 559–577.

Marthaningtyas, M. P. D. (2016). Analysis of self-leadership in compiling a thesis. Empathy – Journal of Guidance and Counseling, 3(2).

Morgan, N. A., Kaleka, A., & Katsikeas, C. S. (2004). Antecedents of export venture performance. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 90–108.

Morris, P., Jamieson, H. A., & Shepherd, M. M. (2006). Research updating the APM Body of Knowledge. International Journal of Project Management, 24(6), 461–473.

Neck, C. P., & Houghton, J. D. (2006). Two decades of self-leadership theory. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(4), 270–295.

Neck, C. P., Manz, C. C., & Houghton, J. D. (2020). Self-leadership: The definitive guide to personal excellence. SAGE.

Neck, C. P., Neck, H. M., Manz, C. C., & Godwin, J. (1999). A self-leadership perspective toward enhancing entrepreneur performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 14(6), 477–501.

Nonnis, M., Massidda, D., Cabiddu, C., Cuccu, S., Pedditzi, M. L., & Cortese, C. G. (2020). Motivation to donate and OCB. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 934.

Ohly, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). Challenging the status quo: What motivates proactive behaviour?. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(4), 623–629.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1993). Citizenship behavior and fairness. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 6, 257–269.

Putra, I. M. A. D., & Sintaasih, D. K. (2018). The effect of self-leadership and organizational commitment. (Doctoral dissertation, Udayana University).

Rank, J., Pace, V. L., & Frese, M. (2004). Creativity, innovation, and initiative. Applied Psychology, 53(4), 518–528.

Räsänen, M. (2017). Leadership in sales organization. (Master's thesis, University of Eastern Finland).

Rioux, S. M., & Penner, L. A. (2001). Causes of OCB: A motivational analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1306–1314.

Sahin, F. (2011). The interaction of self-leadership and psychological climate on job performance. African Journal of Business Management, 5(5), 1787–1794.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sahin, F. (2011). The interaction of self-leadership and psychological climate. African Journal of Business Management, 5(5), 1787–1794.

Srivastava, S., & Pathak, D. (2020). Moderators linking job crafting to OCB. Vision, 24(1), 101–112.

Stewart, et al. (2019). Self-leadership: A paradoxical core of organizational behaviour. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 47–67.

Sukmayanti, N. K., & Sintaasih, D. K. (2018). Perceived support, empowerment, job performance, and OCB. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 20(5), 1–8.

Tang, G., Chen, Y., Knippenberg, D., & Yu, B. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of empowering leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(6), 551–566.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tang, J., Baron, R. A., & Yu, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial alertness. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–30.

Triyanthi, M., & Subudi, M. (2018). Organizational communication, leadership and justice on OCB. E-Jurnal Ekonomi dan Bisnis Universitas Udayana, 7, 837–868.

Vartanian, L. R., Froreich, F. V., & Smyth, J. M. (2016). Serial mediation model for body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 19, 98–103.

Zhang, K., & Cui, Z. (2022). Impact of leader proactivity on follower proactivity. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 781110.

Received: 01-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16269; Editor assigned: 02-Sep-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-16269(PQ); Reviewed: 08-Sep-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-16269; Revised: 18-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16269(R); Published: 30-Sep-2025