Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 3

Gen Z, Instagram Influencers and Hashtags Influence on Purchase Intention of Apparel

Ouya Huang, Kent State University

Lauren Copeland, PhD, Kent State University

Abstract

This study aims to understand Gen Z and their relationship to influencers on #OOTD (Outfit Of The Day) on Instagram and how the credibility of the influencer, parasocial interaction (PSI), physical attractiveness and self-confidence of the influencer are related and ultimately affect the purchase intention of consumers. Approximately 300 participants took part in an online survey. The main finding of this study is physical attractiveness is not as important to consumers as credibility, PSI, and confidence. With PSI being the strongest predictor of purchase intention. Transferring confidence and credibility are the most important aspects to influencing this generation on instagram as well as creating a relationship with followers.

Keywords

Gen Z, Instagram Influencer, Purchase Intention, Consumer Behavior, Parasocial Interaction (PSI).

Introduction

With the increasing number of social media users, social network platforms have become an indispensable part of people's life. Online consumers are not only inclined to get advice from their relatives and friends to buy products or services, they start to turn to products or services recommended or endorsed by celebrities, influencers, or influential people in a certain field. Currently, social media is no longer the continuation of traditional media communication, but the use of influencer marketing to enter the target market of the brand. For many brands, working with influencers can help increase brand awareness and sales. Consumers are increasingly using blogs, social networks to share and discuss web content, which represents a social media phenomenon that can seriously affect a company's reputation, sales and even survival (Kietzmann et al., 2011). Not only can brand pages and fan pages be found on social media, but users can also actively generate and publish multimedia content, including their perceptions of brands and products. Such content, known as user-generated content, has proved more popular and effective than professional advertising (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020; Welbourne & Grant, 2016). These are all forms of social identity, where consumers want recommendations from peers, influencers, and unbiased third parties, rather than the brands selling products.

Influencers are active creators of online content who act as opinion leaders to influence brands, products, and potential users, delivering their opinions to a targeted audience (Chau & Xu, 2012; Susarla et al., 2012). Influencers on instagram often introduce their tested products to provide comments or promote them to other users online. Influencers on Instagram through the tag # OOTD (Outfit Of The Day) to display, resulting in a large number of advertising content (Abidin, 2016). Influencer marketing refers to companies promoting their products through influential people, and accounts with a large number of followers are more likely to attract consumers' interest (De Veirman et al., 2017). Their posts usually take the form of images or videos, including embedded content and text descriptions.

In this digital age, influencers with a specific audience on the Internet are even more effective than celebrity endorsements. The right influencers can help brands reach their target audience, build trust, and then drive participation. They often create original, appealing, brand-friendly content rather than following the advertising model provided by the brand. For many brands, finding and managing relationships with social media influencers is critical. According to the Tomoson (2019), 59% of marketers plan to increase their influencers' marketing budgets year after year. It is also the most cost-effective and fastest-growing online customer acquisition channel, ahead of SEO, paid search and email marketing. In the advertising industry, getting two bucks for every dollar spent on advertising is considered a success, but the average return for influencers is $6.50, and the top 13% of marketers make $20 or more. What matters is not only quantity but also quality. 51% of marketers believe that the quality of customers obtained through influencer marketing channels is better because they spend more money and are more likely to recommend products to their relatives and friends. According to O’Neil-Hart and Blumenstein (2016), 70% of young YouTube subscribers say they identify more with YouTube influencers than with traditional celebrities. You can imagine this isn't just happening on YouTube. This is not just on YouTube, but also on Instagram and other social media. Statista (2018) suggests that there are many other studies in the field of fashion, beauty, parenting and travel that have reported similar results. However, research in managing relationships with social media influencers, which we now call influencer marketing, is still limited (De Veirman, 2018).

Anyone born from 1997 onward is part of a new generation, called Generation Z. Generation Z are the demographic cohort after Generation X (1965-1980) and Generation Y (1981-1996) (Dimock, 2019). Generation Z are very active on social media platforms, they have a good socio-economic background, and it is easy to get information in an economy that is fully urbanized and developing (Yadav & Rai, 2017). This is the generation that grew up with Amazon and Netflix and had the information at their fingertips. They are savvy consumers who distrust brands. In terms of advertising, they like real ads - to look like them instead of perfect real people. As for customer service, they like to be personalized and efficient. They want companies to use the latest data to customize their online and offline shopping experiences (Gutfreund 2016). Due to cultural, economic and technical foundations, social media usage of Generation Z is very self-evident. In the next year or two, Gen Z will account for 40% of all online consumers, 32% of the global total, and have a spending power of $ 44 billion (Lypnytska, 2019). This generation's network habits are significantly different from their predecessors, and companies that want to keep up with them will soon need to relearn, retrain, and replan their marketing strategies.

This article explores how the credibility of the influencer, PSI, physical attractiveness and self-confidence of the influencer are related and affect the purchase intention. The purpose of this study is to better understand Gen Z and their relationship to influencers on Instagram (specifically looking at #ootd) in regards to their feelings of credibility and PSI of the influencer leading to considerations of physical attractiveness and self-confidence of the influencer and their post, ultimately leading to purchase intention from the site.

Literature Review

This research examines the relationship between Generation Z, Instagram influencers and purchase intentions. This study investigates the potential cues, such as credibility, PSI, physical attractiveness, and self-confidence related to fashion influencers present on Instagram specifically through (#ootd posts). #OOTD currently has over 290 million posts on Instagram and started just under ten years ago. It is a worldwide phenomenon that includes standards associated with the posts and is used by every day and celebrity influencers (Instagram #ootd 2020). #OOTD was founded a decade ago by the hashtag’s originator Karla Reed (2020) and was coined a national holiday by reality television star Stassi Schroeder in 2018 (Inniss, 2018). #OOTD posts can be found not only on Instagram but also Tumblr and Pinterest and oftentimes incorporates challenges associated with it and are viewed and posted about all over the world. These phenomena are mostly used by younger females and fashion bloggers but has also become popular among males, celebrities, and international fashion figures.

Instagram is a social networking application that allows users to upload and edit photos, along with hashtags and text. It also integrates many social elements, including the establishment of friendships, reply, sharing, liking and collection. Instagram was first launched in October 2010, adding 50 million users after 19 months of Instagram went public, and adding another 50 million users in the next nine months (Hu et al., 2014). As of September 2013, Instagram has 150 million users, 65 million photos uploaded to Instagram, and one billion "likes" (Malik, 2013, Benady, 2013).

As a social media platform, Instagram has evolved from a single social purpose to a marketing tool. Instagram is now a key marketing component for brands and retailers, and Instagram offers a great opportunity for brands to market with visually valuable photo information (Sprung, 2013). Instagram encourages fans and followers to participate by sharing their information with brands or retailers (Kabani, 2013). Instagram provides a channel to show the characteristics of customers on its instagram platform and participate in it, which in turn improves this connection, making it closer, meaningful and real through the promotion of activities on instagram, and finally turning them into formal customers in this process (Sprung, 2013). Clarke (2019) mentioned that Instagram had more than 1 billion monthly active users, with 72% of teenagers using the platform every day, 59% of those under 30, 39% of women and 30% of men in the United States, and 80% of those outside the United States. Reach an incredible global reach, and users like the estimated 4.2 billion posts per day, 95 million posts per day and 400 million stories per day. Videos on Instagram increased by 80% year on year, and 72% of users bought products they saw on the platform.

Credibility & Purchase Intentions

As for credibility, there are few subjective or emotional factors that affect social influence (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). Credibility is mainly composed of two parts of trustworthiness and expertise (Rogers & Bhowmik, 1970). Trustworthiness is related to the honesty of the speaker, and goodwill reflects his/her concern for the audience (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). Brands will not come to tell customers how good they are. Instead, brands will let influencers, the people that customers trust, to tell customers why they should pay attention to brands’ products and services, because the words of influencers are much more credible to customers. Expertise could be defined as the knowledge and experience an individual possesses in a particular field – one of the main factors of credibility, along with trustworthiness and goodwill (Hovland & Weiss, 1951; McCroskey & Teven, 1999). The influencer is a mutual friend between the brand and the customer. The influencers have good social relations, are authoritative, and have active thinking.

Trusted spokesmen seem more persuasive than untrusted ones (Priester & Petty, 2003). Based on research on endorsement effects, Bergkvist & Zhou (2016) suggest that consumers are more likely to positively evaluate brands and products endorsed by people they believe to be credible. The credibility of influencers plays an important role in consumers' responses to brand attitudes and purchase intentions (Goldsmith et al., 2000).

Perceived spokesperson expertise has a positive impact on product attitudes and purchase intentions (Eisend & Langner, 2010). Especially for influencers, credibility plays an important role in influencing purchasing behavior (Chapple & Cownie, 2017). In research related to Instagram influencers and consumer behavior, we suggest that influencers' credibility is proportional to the audience's purchase intention. For example, influencers can use their expertise and trustworthiness to demonstrate how to validate the expected results of the product being promoted. As a result, lack of trustworthiness and fashion expertise can reduce the credibility of influencers. Based on the literature, researchers formulate their first research hypothesis:

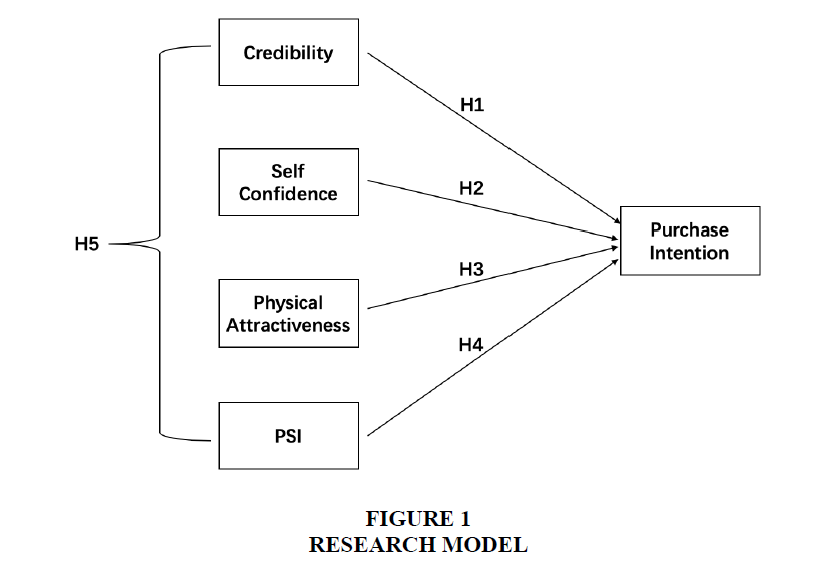

H1: There will be a significant and positive relationship between credibility and purchase intention.

Self-Confidence and Purchase Intention

One's self-confidence comes from mastering the experience of a particular activity (Snyder & Lopez, 2009). Confidence in one's abilities usually increases motivation, and higher confidence enhances the motivation of action (Bénabou & Tirole, 2002). Purchase intention refers to the tendency of the consumer to purchase the product, and is an indication signal of the actual shopping behavior of the consumer (Brown et al., 2003). Personal attitude will affect purchase intention (Kotler & Keller, 2003). Jamieson & Bass (1989) pointed out that although the purchase intention is not the same as the actual purchase behavior, the measure of purchase intention does have a predictive effect. Consumer's purchase intention is a subjective tendency of consumers to products and an important indicator to predict consumer behavior (Chi et al., 2009). Consumers can use online social networks to share and exchange ideas, opinions, and product-related information to generate purchase intent (Balakrishnan et al., 2014). Purchase intentions are formed under the assumption of a pending transaction and are therefore often considered an important indicator of actual purchases (Chang & Wildt, 1994). The concept of the role-relaxed consumer is susceptible to interpersonal influences. They believe that they are educated, knowledgeable, and logical, and are more willing to buy clothing that highlights their self-confidence (Amatulli & Guido, 2011).

Confidence construct is one of the decisive factors of buying intention, confidence is a person's evaluation of the brand is correct to determine the degree of certainty (Howard & Sheth, 1969; Howard, 1989). According to Bennett & Harrell (1975), the subjective certainty of a buyer's judgment on the quality of a brand can be interpreted as having two different theoretical meanings. It may refer to the buyer's overall confidence in the brand. Or it can refer to the buyer's ability to judge or evaluate the attributes of the brand. Brand evaluation is often thought of as a dimensional attitude construct. In other words, a certain (or confident) judgment of one's attitude toward things is seen as reflecting that one has actually developed an attitude toward the object of focus (Laroche et al., 1996). In general, consumers' confidence in brand evaluation, that is, consumers' self-confidence in their ability to judge or evaluate products, is one of the determinants of purchase intention (Laroche et al., 1996). Thus, the second research hypothesis is the following:

H2: There will be a significant and positive relationship between self-confidence and purchase intention.

Physical Attractiveness

Physical Attractiveness refers to the degree to which a person's appearance is considered aesthetically pleasing or beautiful (Berscheid & Walster, 1974). Influencers can use their own appearance to show how to determine the expected results from the products they promote (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). The daily expansion of social media has turned the influencer into a partner around the audience. In order to get consumers' attention, brands must cooperate with people who are consumers willing to pay attention to.

Attractive (compared to unattractive) communicators are always more popular, considered to be more favorable conditions, and have a positive impact on the products they are associated with (Joseph, 1982). As the communicator of information, influencers have an invaluable role, and the influence of influencers on their physical attractiveness will affect their persuasiveness. Physical attractiveness is a usable resource in social influence (Mills & Aronson, 1965). Attractive speakers influence their audience through the identification process. The audience will feel like the speaker or want to be like the speaker and build a positive relationship with him / her (Kelman, 1958). The influencers are leaders in their field, who have established a high level of trust and two-way communication channels with their fans. As a result, celebrities and online influencers launch fashion and other trends that their followers admire. When the recipient sees him/her as someone they can rely on, the influencer has more influence (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). Therefore, researchers hypothesize:

H3: There will be a significant and positive relationship between physical attractiveness and purchase intention.

Parasocial Interaction Theory

Parasocial interaction (PSI) theory began in the 1950’s from communication literature/research and was created to develop an explanation of the relationships that were forming between consumers and television and radio (Horton & Wohl, 1956). PSI is defined as

“An illusionary experience, such that consumers interact with personas (i.e. mediated representations of presenters, celebrities, or characters) as if they are present and engage in a reciprocal relationship” (Labrecque, 2014).

This is relevant to the topic of celebrity influencers and brands as friends on social media platforms such as Instagram. Many researchers argue that PSI can arise from one initial reaction, isolated reactions, to even long periods of relationship building (Perse & Rubin, 1989; Hartman & Goldhoorn, 2011). PSI can be mediated through a person (in this study’s case a celebrity) or also through design and the presentation of information (the brand) (Hoerner, 1999). Labrecque (2014) makes the case that these phenomena can be developed through brands and celebrities and not just mass media.

PSI has two meanings: people react to media characters such as celebrities, actors, and presenters; and this reaction is like people are talking face-to-face with real friends (Hartmann, 2008). In fact, it means that when viewers use social media, they will have a kind of relationship with people on the screen consciously or unconsciously. The concept of PSI grew out of communications literature and offered to develop the relationship between consumers and the mass media. In the process of media consumption, the audience will naturally imagine the media characters as people who can be reached in daily life, react accordingly, and thus create an intimate connection (Horton & Wohl, 1956). Long-term PSI will form social relationships similar to those formed by people through face-to-face interactions, that is, parasocial relationships (Perse & Rubin, 1989). This relationship is often wishful thinking, although this relationship is not strongly perceived as the relationship between people in real life. But it does exist objectively. PSI can be used to describe the relationship between fans and celebrities, and long-distance one-way interactions enhance emotional dependence (Giles, 2002). PSI between celebrities and the public is divided into three levels: cognitions, emotions and behavior, which respectively correspond to the three forms of communication around the content of communication, the public and celebrity emotional exchanges, and self-internalization of the public to celebrity behavior (Klimmt et al., 2006).

At the cognitive level, the public is sensible (Perse & Rubin, 1989). They determine whether or not to conduct such behavior in the future by measuring the degree of satisfaction and the value of the content of the communication: if expectations are always realized, a habitual mode of media use is established. The primary purpose of public contact with the media is to obtain information and the position of the mass media on specific events. Celebrities are the bridge between the media and the public. Therefore, they can clearly convey information and media positions in their own way to meet the public's expectations of information. It is the basic quality of celebrities.

The purpose of the public's use of the media's emotional orientation is to satisfy their emotional needs and to have a sense of pleasure (Perse & Rubin, 1989). To a large extent, the audience has an emotional identity with the unique style of celebrities. Once this identity is generated, it is relatively stable and difficult to change. The key to the success of celebrities lies in their ability to achieve the PSI interaction of emotional level with the public (Hartmann, 2008). This kind of communication has been deepened from the previous cognition of the content of communication to the attitude of celebrities. Once formed, it will be deeply rooted in the hearts of the people. At this time, the audience's dependence on celebrities is extremely strong.

The influence of celebrities comes from the appeal of their content and the public's emotional dependence on them. In the long run, they will further influence the public's behavior and enable the public to achieve their social interactions in action (Perse & Rubin, 1989). People's social behavior is the result of observation and learning, and imitation becomes the most direct way of socialization (Bandura & Walters, 1977). This level of communication is the product of the public's emotional dependence on celebrities. At this time, the influence of celebrities has extended to the real life of the public.

Compared with celebrities, the images of influencers on social media are ordinary, approachable and authentic, which makes the audience feel more like them or close to them (Chapple & Cownie, 2017; Schouten et al., 2019). Influencers often refer to users who "follow" them on social media as "followers," rather than "fans," because the term masks a sense of status promotion and social distance between influencers and their followers (Marwick & boyd, 2011; Abidin, 2015). Online social network users can build this relationship with influencers by following their home page and following their posts on instagram. Multiple followers can form an online community in which members share similar values, beliefs and interests with influencers (Nambisan & Watt, 2011). Influencers who are able to connect with their audience are more effective at persuasion, probably because of the parasocial relationship they have with that unique influencer (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). For example, young women follow celebrities and influencers on Instagram, which has an impact on their followers. But as followers become more connected to them, digital personalities seem more persuasive and credible (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017). Sokolova & Kefi (2020) note that PSI between Instagram influencers and their followers have a positive impact on luxury brand perceptions. Thus, leading to hypotheses 4 and 5.

H4: There will be a significant and positive relationship between PSI and purchase intention.

H5: PSI will explain the most significant addition to purchase intention above credibility, attractiveness and self-confidence.

See Figure 1 for the model of the study.

Methodology

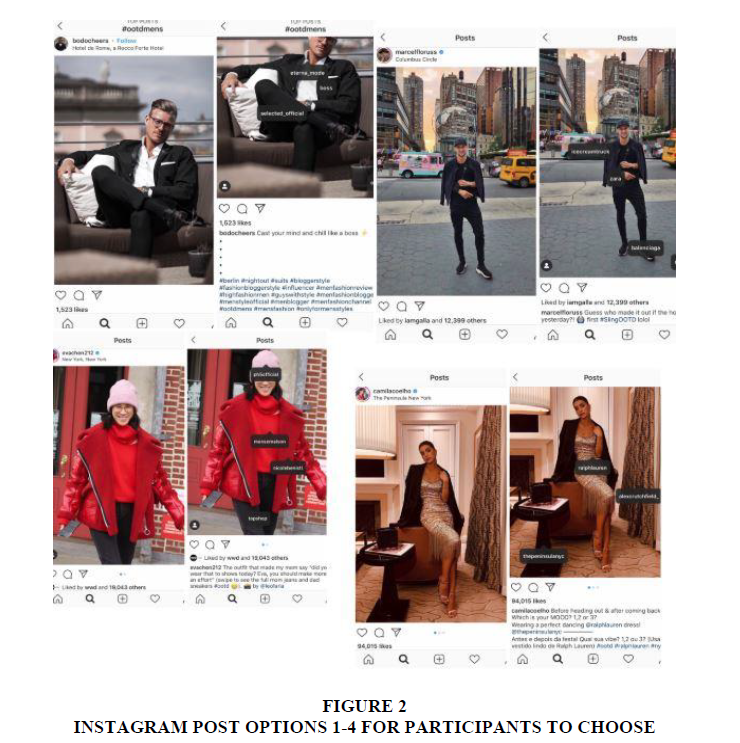

The study was conducted using the online survey platform qualtrics. A convenience sample of students in an introductory fashion course at a large Midwestern University took part in the study. Because of this, there was an uneven balance of females to males and a younger audience of 18-20 years old which is acknowledged in the implications of this study. Participants were able to choose a pair of photographs showcasing an Instagram influencer and their original post as well as a view of the post with the tags of designer clothes worn by the influencer showing. See figure two. Participants chose one set of photos between two options for men and two options for women based on their preference. This allowed us to better understand what they deemed most interesting to them and to understand through the survey how they would directly react to a post on their own Instagram that they preferred over the other options. This was done in order to allow them to have a more authentic Instagram experience. According to Action Regulation Theory (Hacker, 1986) an individual deals consciously, planning and purposeful with his/her environment, appeals actively on the environment in this case instagram and through the choice associated not only does the environment change, but also the individual and his/her personality towards the post and shows us the holistic individual and their motive for preferences (Hacker 2005, Oesterreich, 1987, Schelten, 2002, Wiendieck,1993). They were then asked a series of questions pertaining to the post they chose related to credibility, social interaction, physical attractiveness, and self-confidence, as well as purchase intention. The most popular choice among this group was the lower right post (n= 154) followed by the lower left (n= 94) and the top right (n=27), top left (n=15). See Figure 2.

The survey consisted of 26 questions. Six questions pertaining to credibility were utilized from Lim et al. (2017), for example, “I find this influencer trustworthy”, and “I find this influencer expert in her domain.” Parasocial Interaction had 5 items from Sokolova & Kefi, (2019) and Labrecque, (2014), such as I would follow her and interact with her on other “social networking sites”, and This influencer makes me feel comfortable, as if I am with a friend. Physical attractiveness included 3 items from Sokolova & Kefi, (2019); Kahle & Homer, (1985), including “I think this influencer is pretty.” Self-confidence came from Jain et al., 2014; Shim et al., (1991) had 3 items including “The apparel I see in this post would bring me confidence.” and “I have the ability to choose the right apparel for myself after seeing this post.” Finally, Purchase intention from Hyllegard, Yan, Ogle & Lee, 2012; Sokolova & Kefi, 2019 had 2 items including “In the future I will intend to buy this item I see in the post.”

All items were placed on a 3 pt likert scale (1: Disagree; 2: Neutral; 3: Agree) to discourage survey fatigue. Cummins & Gullone (2002) state

“It is still true that the kinds of psychometric data researchers report in support of their scales are generally restricted to reliability (internal and test-retest) and convergent/divergent validity which is, itself, highly dependent on reliability. This narrow focus has led, inexorably, to the view that smaller, rather than larger numbers of scale points are advantageous to measurement e.g. Cronbach, (1946).”

Peabody (1962) found the directional component of the Likert scale over the intensity component and that a two-point or dichotomous agreement scale of either agree or disagree was favorable. This hypothesis was later supported by Komorita (1963), Komorita & Graham (1965), Bendig (1954), Peabody (1962), Jacoby & Matell (1971) and Matell & Jacoby (1972). There is a “relative irrelevance of additional scale choices to assess intensity” (Munshi, 2014).

Correlations and a hierarchical regression were conducted to understand the significance between variables and their relationship if any with purchase intention.

Results

A total of 304 respondents completed the online survey from a large midwestern university. A majority of the respondents were female (88.4%, n= 268) and 18 years old (66.3%, n=197). When asked about their usage of Instagram a majority of respondents indicated they access Instagram 9 or more times a day (35.9%, n=109). The most popular Instagram influencer they followed was Kylie Jenner and Kim Kardashian (with many indicating they followed the entire family also), Zendaya, Jeffrey Star, Emma Chamberlin, Bella Hadid, Rihanna, Aimee Song, and Tezza, proving that celebrity is still a possible influential component on social media for this generation. See Table 1 for the full breakdown of the demographics of the study.

| Table 1: Demographics | ||

| Item | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male= 35 | 11.30% |

| Female= 274 | 88.40% | |

| Other= 1 | 0.30% | |

| Age (in years) | 18=204 | 65.80% |

| 19=73 | 23.60% | |

| 20=18 | 5.80% | |

| 21=4 | 1.30% | |

| 22=1 | 0.40% | |

| 23=1 | 0.40% | |

| 24=3 | 1.00% | |

| Do you consider yourself an active user of Instagram? | Yes= 277 | 89.40% |

| Maybe= 19 | 6.10% | |

| No= 14 | 4.50% | |

| How often do you access Instagram per day? | 0-2 times=16 | 5.20% |

| 3-5 times=67 | 21.60% | |

| 6-8 times=100 | 32.30% | |

| More than 9 times= 109 | 35.20% | |

| Do you follow the hashtag #OOTD? | Yes=203 | 76.70% |

| No=61 | 23.00% | |

| Do you follow Fashion Influencers on Instagram? | AR=46 | 17.40% |

| VR=93 | 35.10% | |

| Both=125 | 47.20% | |

All scales were found reliable with Cronbach’s Alpha >.7. Correlations were conducted to determine the individual relationships between the variables and a hierarchical regression was conducted to determine the strongest contributing factor to purchase intention from an #ootd post by an instagram influencer. All correlations between variables were found highly significant at p=0.000 level except for purchase intention and physical attractiveness but that was still found to be significant (p=0.021). This could be less notable as the participants selected the pair of photographs leading to physical attractiveness bias. There was no presence of multicollinearity found leading us to the hierarchical regression. It was found that 46.2% of purchase intention variation was explained by credibility, PSI, physical attractiveness, and confidence (R=0.462) with the strongest contributing factor being PSI (B=0.314, sig.=0.000) followed by Confidence (B=0.273, sig. =0.000). H1, H2, and H4 were all accepted with H3 being rejected as it was not significant. H5 was rejected as credibility served to be the main contributor to purchase intention ovr PSI, Self-confidence and attractiveness. See Table 2.

| Table 2: Findings | ||||||

| Variable | R2 | R2 Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credibility | 0.046 | 0.046 | 13.756 | 1 | 284 | 0.000* |

| PSI | 0.158 | 0.111 | 37.413 | 1 | 283 | 0.000* |

| Physical Attractiveness | 0.158 | 0 | 0.021 | 1 | 282 | 0.886 |

| Self Confidence | 0.213 | 0.056 | 19.873 | 1 | 281 | 0.000* |

*= p<0.001

Discussion and Implications

Overall, this study was surprising as not many gen z consumers follow hashtags but have more personal relationships with influencers as individuals. The hashtag phenomena may be something based on earlier reiterations of previous generations finding ways to organize their thoughts and process their individual PSI. Credibility, PSI and self-confidence are all positively correlated with purchase intention, that is, credibility influencers who care about their followers and subject matters that show expertise are more likely to have long-term followers and they are willing to buy products that influencers introduce. For young Gen Zs, making them willing to buy a product is directly related to having a credible influencer they follow, which demonstrates the importance of brands creating such a link. As a result, a brand targeting Gen Z would find potential customers to be the most focused and even addictive followers. As for influencers, they should not only focus on community development and creating valuable content, but also care about the followers they have gained to build strong parasocial relationships. Brands should understand the values conveyed by influencers, as well as the values of potential customers, because bloggers have more influence over followers who like them (Dwivedi et al., 2015). Therefore, brand content should be relevant to the same value as influencers. Influencers can use this insight to share these values with more consumers, increasing the credibility of influencers and building parasocial relationships with followers. According to this study, Physical attractiveness did not hold as much weight as credibility and was not a significant influence in participants' considerations and judgements of an instagram influencer post. However, in addition to credibility, PSI, and confidence prove to be pertinent to the influencer and the posts themselves. An influencer must focus on their image online and whether or not what they are promoting they are knowledgeable about and their image is directly related to the product. Influencers are not going away with this generation and hold a lot of power as buying direct from Instagram is becoming more popular. Transferring confidence and credibility are the most important aspects to influencing this generation on instagram as well as creating a relationship with followers. Responding to comments and interacting with followers creates the sense of PSI and encourages this generation to care about what happens to the influencer.

By exuding confidence, the influencer also transfers confidence to their followers and encourages purchase intention of what they are promoting. Educators and academics of social media and social network management need to take into account the difference not just between generations and gender but also of popular movements on social media and their implications to an entire industry for example apparel and retail. The results of this study help brands and influencers to establish a relationship with customers based on their parasocial interaction abilities. For brands, it is important to understand the implications of these influences on consumers, so that consumers' needs can be more clearly defined and the brand products can be promoted. This is also beneficial for influencers who want to use more persuasive techniques while creating content and collaborating with brands on ratings. As our technology pushes us into faster fashion cycles that are more homogenous globally educators and researchers need to take into account how this impact and changes the entire marketing landscape but also targeting specific consumers and marketers in different ways.

Limitations and Future Research

Limitations of this research include the vast differences in gender in this study. Future research should include looking at the difference between gender and the specifics of how PSI is created among this generation. Unfortunately, a majority of participants were female which skewed the data. An additional limitation as well, was the measurement tools utilized. Many of these users follow specific influencers on Instagram and targeting those specific followers and not just general fashion influencers could pose more understanding of the phenomena on the platform and purchase intention. Purchasing online and through Instagram is something these participants are used to and take part in but finding ways in which to be more detailed and specific in how to make influencers worth the cost is something that brands can continue to target. There is also a need to look at the differences not just between generations but also cultural differences how those exist on a global platform such as Instagram. The habits and patterns of gen z are important but the questions must be asked is it a geographical phenomenon or are there differences between, cultures, countries, urbanization etc. There was a time that indicated the trend and movement of fashion based on runway shows and already expected fashion calendars. With the advent and takeover of social media and this new generation, which is the first to have been fully immersed in it, coupled with the changing retail, marketing, and advertising landscape researchers must focus on these phenomena quickly as trends and patterns within online society are moving more and more quickly. This study calls for a need to step back to better understand what makes a post influencing as it may not be the already known celebrity persona specifically, but could indicate there is a need to study the presentation of posts that actually provides the sense of credibility and creates a PSI relationship between the influencer and customer.

References

Abidin, C. (2015). Communicative intimacies: Influencers and perceived interconnectedness. Ada, 8, 1-16.

Abidin, C. (2016). Visibility labour: Engaging with Influencers’ fashion brands and# OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media International Australia, 161(1), 86-100.

Amatulli, C., & Guido, G. (2011). Determinants of purchasing intention for fashion luxury goods in the Italian market. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal.

Balakrishnan, B.K., Dahnil, M.I., & Yi, W.J. (2014). The impact of social media marketing medium toward purchase intention and brand loyalty among generation Y. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 148, 177-185.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R.H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-hall.

Bendig, A.W. (1954). Reliability and the number of rating-scale categories. Journal of Applied Psychology, 38(1), 38.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2002). Self-confidence and personal motivation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 871-915.

Benady, D. (2013). How marketers use Pinterest and Instagram to win customers: Social media plus strong imagery makes a compelling combination. The Guardian.

Bennett, P.D., & Harrell, G.D. (1975). The role of confidence in understanding and predicting buyers' attitudes and purchase intentions. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(2), 110-117.

Bergkvist, L., & Zhou, K.Q. (2016). Celebrity endorsements: a literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Advertising, 35(4), 642-663.

Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1974). Physical attractiveness. In Advances in experimental social psychology, 7, 157-215. Academic Press.

Brown, M., Pope, N., & Voges, K. (2003). Buying or browsing?. European Journal of Marketing.

Chang, T.Z., & Wildt, A.R. (1994). Price, product information, and purchase intention: An empirical study. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(1), 16-27.

Chapple, C., & Cownie, F. (2017). An investigation into viewers’ trust in and response towards disclosed paid-for-endorsements by YouTube lifestyle vloggers. Journal of Promotional Communications, 5(2).

Chau, M. & Xu, J. (2012). Business intelligence in blogs: Understanding consumer interactions and communities. MIS Quarterly, 1189-1216.

Chi, H.K., Yeh, H.R., & Yang, Y.T. (2009). The impact of brand awareness on consumer purchase intention: The mediating effect of perceived quality and brand loyalty. The Journal of International Management Studies, 4(1), 135-144.

Clarke, T. (2019). 24+ Instagram statistics that matter to marketers in 2019. Hootsuite [online] Available at: <https://blog.hootsuite.com/instagram-statistics/>

Cronbach, L.J. (1946). A case study of the split half reliability coefficient. Journal of Educational Psychology, 37(8), 473.

Cummins, R.A., & Gullone, E. (2000). Why we should not use 5-point Likert scales: The case for subjective quality of life measurement. In Proceedings, second international conference on quality of life in cities, 74, 93.

De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: the impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798-828.

Dimock, M. (2019). Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center, 17, 1-7.

Dwivedi, Y.K., Kapoor, K.K., & Chen, H. (2015). Social media marketing and advertising. The Marketing Review, 15(3), 289-309.

DMI, (2019). 20 Influencer Marketing Statistics that Will Surprise You. Digital Marketing Institute [online] Available at: https://digitalmarketinginstitute.com/blog/20-influencer-marketing-statistics-that-will-surprise-you

Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities' Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 1-7.

Eisend, M., & Langner, T. (2010). Immediate and delayed advertising effects of celebrity endorsers’ attractiveness and expertise. International Journal of Advertising, 29(4), 527-546.

Giles, D.C. (2002). Parasocial interaction: A review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychology, 4(3), 279-305.

Goldsmith, R.E., Lafferty, B.A., & Newell, S.J. (2000). The impact of corporate credibility and celebrity credibility on consumer reaction to advertisements and brands. Journal of Advertising, 29(3), 43-54.

Gutfreund, J. (2016). Move over, Millennials: Generation Z is changing the consumer landscape. Journal of Brand Strategy, 5(3), 245-249.

Hacker, W. (1986). Arbeitspsychologie (Vol. 41). Stuttgart: Verlag Hans Huber.

Hacker, W. (2005). Allgemeine Arbeitspsychologie: Psychische Regulation von Wissens-Denk-und körperlicher Arbeit. Huber.

Hartmann, T. (2008). Parasocial interactions and paracommunication with new media characters. Mediated Interpersonal Communication, 177, 199.

Hovland, C.I., & Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 15(4), 635-650.

Horton, D., & Wohl, R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215-229.

Howard, J.A., & Sheth, J.N. (1969). The theory of buyer behavior (No. 658.834 H6).

Howard, J.A. (1989). Consumer behavior in marketing strategy. Prentice Hall.

Hu, Y., Manikonda, L., & Kambhampati, S. (2014) May. What we instagram: A first analysis of instagram photo content and user types. In Eighth International AAAI conference on weblogs and social media.

Inniss, C. (2018). Stassi Schroeder Invented National #OOTD Day So You Can 'Put Your Best Outfit Forward'. Instagram #ootd, 2020. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/ootd/?hl=en

Jain, V., Vatsa, R., & Jagani, K. (2014). Exploring Generation Z's Purchase Behavior towards Luxury Apparel: a Conceptual Framework. Romanian Journal of Marketing, 2.

Jamieson, L.F., & Bass, F.M. (1989). Adjusting stated intention measures to predict trial purchase of new products: A comparison of models and methods. Journal of Marketing Research, 26(3), 336-345.

Joseph, W.B., 1982. The credibility of physically attractive communicators: A review. Journal of Advertising, 11(3), 15-24.

Kabani, S. (2013). Ten tactical ways to market your apparel brand using social media.

Kelman, H.C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(1), 51-60.

Kietzmann, J.H., Hermkens, K., McCarthy, I.P., & Silvestre, B.S. (2011). Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Business Horizons, 54(3), 241-251.

Klimmt, C., Hartmann, T., & Schramm, H. (2006). Parasocial interactions and relationships. Psychology of Entertainment, 291-313.

Komorita, S.S. (1963). Attitude content, intensity, and the neutral point on a Likert scale. The Journal of social psychology, 61(2), 327-334.

Komorita, S.S., & Graham, W.K. (1965). Number of scale points and the reliability of scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 25(4), 987-995.

Kotler, P., & Keller, K.L. (2003). Marketing management (International edition, p. 11).

Kowalczyk, C.M., & Pounders, K.R. (2016). Transforming celebrities through social media: The role of authenticity and emotional attachment. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

Labrecque, L.I. (2014). Fostering consumer–brand relationships in social media environments: The role of parasocial interaction. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 134-148.

Laroche, M., Kim, C., & Zhou, L. (1996). Brand familiarity and confidence as determinants of purchase intention: An empirical test in a multiple brand context. Journal of Business Research, 37(2), 115-120.

Lypnytska, O. (2019). Marketing to Generation Z: 11 important things to keep in mind. PushPushGo [online]

Malik, O. (2013). Instagram growth up sharply, says it has 150 million users. Gigaom. Com [online] Available at:<http://gigaom.com/2013/09/08/instagram-growth-up-sharply-says-it-has-150-millionusers/>

Matell, M.S., & Jacoby, J. (1972). Is there an optimal number of alternatives for Likert-scale items? Effects of testing time and scale properties. Journal of Applied Psychology, 56(6), 506.

McCroskey, J.C., & Teven, J.J. (1999). Goodwill: A reexamination of the construct and its measurement. Communications Monographs, 66(1), 90-103.

Marwick, A.E., & Boyd, D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114-133.

Mills, J., & Aronson, E. (1965). Opinion change as a function of the communicator's attractiveness and desire to influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1(2), 173.

Munshi, J. (2014). A method for constructing Likert scales. Available at SSRN 2419366.

Nambisan, P., & Watt, J.H. (2011). Managing customer experiences in online product communities. Journal of Business Research, 64(8), 889-895.

Oesterreich, R. (1987). Handlungspsychologie. Kurseinheit 1: Handlungsregulationstheorie Kursunterlagen, Fernuniversität-Gesamthochschule, Hagen.

O’Neil-Hart, C., & Blumenstein, H. (2016). Why YouTube Stars Are More Influential Than Traditional Celebrities. Think With Google [online] Available at:<https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/youtube-stars-influence/>

Peabody, D. (1962). Two components in bipolar scales: Direction and extremeness. Psychological Review, 69(2), 65.

Perse, E.M., & Rubin, R.B. (1989). Attribution in social and parasocial relationships. Communication Research, 16(1), 59-77. People. Com[online] Available at: <https://people.com/style/stassi-schroeder-vanderpump-rules-national-ootd-day-interview/>

Yadav, G., & Rai, J. (2017). The Generation Z and their Social Media Usage: A Review and a Research Outline. Global Journal of Enterprise Information System, 9(2).

Priester, J.R., & Petty, R.E. (2003). The influence of spokesperson trustworthiness on message elaboration, attitude strength, and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(4), 408-421. Queen of the Instagram #OOTD: Meet Karla Reed, 2020. HEYMAMA [online] Available at: https://heymama.co/queen-of-instagram-ootd-karla-reed/

Rogers, E.M., & Bhowmik, D.K. (1970). Homophily-heterophily: Relational concepts for communication research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 34(4), 523-538.

Schelten, A. (2002). Über den Nutzen der Handlungsregulationstheorie für die Berufs-und Arbeitspädagogik. Pädagogische Rundschau, 56(6), 621-630.

Schouten, A.P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2019). Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 1-24.

Snyder, C.R., & Lopez, S.J. eds. (2009). Oxford handbook of positive psychology. Oxford library of psychology.

Sprung, R. (2013). 5 ways marketers can use Instagram. Social Media Examiner [online] Available at: <http://www.socialmediaexaminer.com/5-ways-marketers-can-use-instagram/>

Snyder, C.R., & Lopez, S.J. eds. (2009). Oxford handbook of positive psychology. Oxford library of psychology.

Sokolova, K., & Kefi, H. (2020). Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53.

Statista, S. (2018). Statista dossier on influencer marketing in the United States and worldwide.

Susarla, A., Oh, J.H., & Tan, Y. (2012). Social networks and the diffusion of user-generated content: Evidence from YouTube. Information Systems Research, 23(1), 23-41.

Welbourne, D.J., & Grant, W.J. (2016). Science communication on YouTube: Factors that affect channel and video popularity. Public Understanding of Science, 25(6), 706-718.

Wiendieck, G. (1993). Einführung in die Arbeits und Organisationspsychologie. (Fernstudienkurs 04751). Hagen: Fern Universität.

Keywords

Gen Z, Instagram Influencer, Purchase Intention, Consumer Behavior, Parasocial Interaction (PSI).

Introduction

With the increasing number of social media users, social network platforms have become an indispensable part of people's life. Online consumers are not only inclined to get advice from their relatives and friends to buy products or services, they start to turn to products or services recommended or endorsed by celebrities, influencers, or influential people in a certain field. Currently, social media is no longer the continuation of traditional media communication, but the use of influencer marketing to enter the target market of the brand. For many brands, working with influencers can help increase brand awareness and sales. Consumers are increasingly using blogs, social networks to share and discuss web content, which represents a social media phenomenon that can seriously affect a company's reputation, sales and even survival (Kietzmann et al., 2011). Not only can brand pages and fan pages be found on social media, but users can also actively generate and publish multimedia content, including their perceptions of brands and products. Such content, known as user-generated content, has proved more popular and effective than professional advertising (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020; Welbourne & Grant, 2016). These are all forms of social identity, where consumers want recommendations from peers, influencers, and unbiased third parties, rather than the brands selling products.

Influencers are active creators of online content who act as opinion leaders to influence brands, products, and potential users, delivering their opinions to a targeted audience (Chau & Xu, 2012; Susarla et al., 2012). Influencers on instagram often introduce their tested products to provide comments or promote them to other users online. Influencers on Instagram through the tag # OOTD (Outfit Of The Day) to display, resulting in a large number of advertising content (Abidin, 2016). Influencer marketing refers to companies promoting their products through influential people, and accounts with a large number of followers are more likely to attract consumers' interest (De Veirman et al., 2017). Their posts usually take the form of images or videos, including embedded content and text descriptions.

In this digital age, influencers with a specific audience on the Internet are even more effective than celebrity endorsements. The right influencers can help brands reach their target audience, build trust, and then drive participation. They often create original, appealing, brand-friendly content rather than following the advertising model provided by the brand. For many brands, finding and managing relationships with social media influencers is critical. According to the Tomoson (2019), 59% of marketers plan to increase their influencers' marketing budgets year after year. It is also the most cost-effective and fastest-growing online customer acquisition channel, ahead of SEO, paid search and email marketing. In the advertising industry, getting two bucks for every dollar spent on advertising is considered a success, but the average return for influencers is $6.50, and the top 13% of marketers make $20 or more. What matters is not only quantity but also quality. 51% of marketers believe that the quality of customers obtained through influencer marketing channels is better because they spend more money and are more likely to recommend products to their relatives and friends. According to O’Neil-Hart and Blumenstein (2016), 70% of young YouTube subscribers say they identify more with YouTube influencers than with traditional celebrities. You can imagine this isn't just happening on YouTube. This is not just on YouTube, but also on Instagram and other social media. Statista (2018) suggests that there are many other studies in the field of fashion, beauty, parenting and travel that have reported similar results. However, research in managing relationships with social media influencers, which we now call influencer marketing, is still limited (De Veirman, 2018).

Anyone born from 1997 onward is part of a new generation, called Generation Z. Generation Z are the demographic cohort after Generation X (1965-1980) and Generation Y (1981-1996) (Dimock, 2019). Generation Z are very active on social media platforms, they have a good socio-economic background, and it is easy to get information in an economy that is fully urbanized and developing (Yadav & Rai, 2017). This is the generation that grew up with Amazon and Netflix and had the information at their fingertips. They are savvy consumers who distrust brands. In terms of advertising, they like real ads - to look like them instead of perfect real people. As for customer service, they like to be personalized and efficient. They want companies to use the latest data to customize their online and offline shopping experiences (Gutfreund 2016). Due to cultural, economic and technical foundations, social media usage of Generation Z is very self-evident. In the next year or two, Gen Z will account for 40% of all online consumers, 32% of the global total, and have a spending power of $ 44 billion (Lypnytska, 2019). This generation's network habits are significantly different from their predecessors, and companies that want to keep up with them will soon need to relearn, retrain, and replan their marketing strategies.

This article explores how the credibility of the influencer, PSI, physical attractiveness and self-confidence of the influencer are related and affect the purchase intention. The purpose of this study is to better understand Gen Z and their relationship to influencers on Instagram (specifically looking at #ootd) in regards to their feelings of credibility and PSI of the influencer leading to considerations of physical attractiveness and self-confidence of the influencer and their post, ultimately leading to purchase intention from the site.

Literature Review

This research examines the relationship between Generation Z, Instagram influencers and purchase intentions. This study investigates the potential cues, such as credibility, PSI, physical attractiveness, and self-confidence related to fashion influencers present on Instagram specifically through (#ootd posts). #OOTD currently has over 290 million posts on Instagram and started just under ten years ago. It is a worldwide phenomenon that includes standards associated with the posts and is used by every day and celebrity influencers (Instagram #ootd 2020). #OOTD was founded a decade ago by the hashtag’s originator Karla Reed (2020) and was coined a national holiday by reality television star Stassi Schroeder in 2018 (Inniss, 2018). #OOTD posts can be found not only on Instagram but also Tumblr and Pinterest and oftentimes incorporates challenges associated with it and are viewed and posted about all over the world. These phenomena are mostly used by younger females and fashion bloggers but has also become popular among males, celebrities, and international fashion figures.

Instagram is a social networking application that allows users to upload and edit photos, along with hashtags and text. It also integrates many social elements, including the establishment of friendships, reply, sharing, liking and collection. Instagram was first launched in October 2010, adding 50 million users after 19 months of Instagram went public, and adding another 50 million users in the next nine months (Hu et al., 2014). As of September 2013, Instagram has 150 million users, 65 million photos uploaded to Instagram, and one billion "likes" (Malik, 2013, Benady, 2013).

As a social media platform, Instagram has evolved from a single social purpose to a marketing tool. Instagram is now a key marketing component for brands and retailers, and Instagram offers a great opportunity for brands to market with visually valuable photo information (Sprung, 2013). Instagram encourages fans and followers to participate by sharing their information with brands or retailers (Kabani, 2013). Instagram provides a channel to show the characteristics of customers on its instagram platform and participate in it, which in turn improves this connection, making it closer, meaningful and real through the promotion of activities on instagram, and finally turning them into formal customers in this process (Sprung, 2013). Clarke (2019) mentioned that Instagram had more than 1 billion monthly active users, with 72% of teenagers using the platform every day, 59% of those under 30, 39% of women and 30% of men in the United States, and 80% of those outside the United States. Reach an incredible global reach, and users like the estimated 4.2 billion posts per day, 95 million posts per day and 400 million stories per day. Videos on Instagram increased by 80% year on year, and 72% of users bought products they saw on the platform.

Credibility & Purchase Intentions

As for credibility, there are few subjective or emotional factors that affect social influence (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). Credibility is mainly composed of two parts of trustworthiness and expertise (Rogers & Bhowmik, 1970). Trustworthiness is related to the honesty of the speaker, and goodwill reflects his/her concern for the audience (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). Brands will not come to tell customers how good they are. Instead, brands will let influencers, the people that customers trust, to tell customers why they should pay attention to brands’ products and services, because the words of influencers are much more credible to customers. Expertise could be defined as the knowledge and experience an individual possesses in a particular field – one of the main factors of credibility, along with trustworthiness and goodwill (Hovland & Weiss, 1951; McCroskey & Teven, 1999). The influencer is a mutual friend between the brand and the customer. The influencers have good social relations, are authoritative, and have active thinking.

Trusted spokesmen seem more persuasive than untrusted ones (Priester & Petty, 2003). Based on research on endorsement effects, Bergkvist & Zhou (2016) suggest that consumers are more likely to positively evaluate brands and products endorsed by people they believe to be credible. The credibility of influencers plays an important role in consumers' responses to brand attitudes and purchase intentions (Goldsmith et al., 2000).

Perceived spokesperson expertise has a positive impact on product attitudes and purchase intentions (Eisend & Langner, 2010). Especially for influencers, credibility plays an important role in influencing purchasing behavior (Chapple & Cownie, 2017). In research related to Instagram influencers and consumer behavior, we suggest that influencers' credibility is proportional to the audience's purchase intention. For example, influencers can use their expertise and trustworthiness to demonstrate how to validate the expected results of the product being promoted. As a result, lack of trustworthiness and fashion expertise can reduce the credibility of influencers. Based on the literature, researchers formulate their first research hypothesis:

H1: There will be a significant and positive relationship between credibility and purchase intention.

Self-Confidence and Purchase Intention

One's self-confidence comes from mastering the experience of a particular activity (Snyder & Lopez, 2009). Confidence in one's abilities usually increases motivation, and higher confidence enhances the motivation of action (Bénabou & Tirole, 2002). Purchase intention refers to the tendency of the consumer to purchase the product, and is an indication signal of the actual shopping behavior of the consumer (Brown et al., 2003). Personal attitude will affect purchase intention (Kotler & Keller, 2003). Jamieson & Bass (1989) pointed out that although the purchase intention is not the same as the actual purchase behavior, the measure of purchase intention does have a predictive effect. Consumer's purchase intention is a subjective tendency of consumers to products and an important indicator to predict consumer behavior (Chi et al., 2009). Consumers can use online social networks to share and exchange ideas, opinions, and product-related information to generate purchase intent (Balakrishnan et al., 2014). Purchase intentions are formed under the assumption of a pending transaction and are therefore often considered an important indicator of actual purchases (Chang & Wildt, 1994). The concept of the role-relaxed consumer is susceptible to interpersonal influences. They believe that they are educated, knowledgeable, and logical, and are more willing to buy clothing that highlights their self-confidence (Amatulli & Guido, 2011).

Confidence construct is one of the decisive factors of buying intention, confidence is a person's evaluation of the brand is correct to determine the degree of certainty (Howard & Sheth, 1969; Howard, 1989). According to Bennett & Harrell (1975), the subjective certainty of a buyer's judgment on the quality of a brand can be interpreted as having two different theoretical meanings. It may refer to the buyer's overall confidence in the brand. Or it can refer to the buyer's ability to judge or evaluate the attributes of the brand. Brand evaluation is often thought of as a dimensional attitude construct. In other words, a certain (or confident) judgment of one's attitude toward things is seen as reflecting that one has actually developed an attitude toward the object of focus (Laroche et al., 1996). In general, consumers' confidence in brand evaluation, that is, consumers' self-confidence in their ability to judge or evaluate products, is one of the determinants of purchase intention (Laroche et al., 1996). Thus, the second research hypothesis is the following:

H2: There will be a significant and positive relationship between self-confidence and purchase intention.

Physical Attractiveness

Physical Attractiveness refers to the degree to which a person's appearance is considered aesthetically pleasing or beautiful (Berscheid & Walster, 1974). Influencers can use their own appearance to show how to determine the expected results from the products they promote (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). The daily expansion of social media has turned the influencer into a partner around the audience. In order to get consumers' attention, brands must cooperate with people who are consumers willing to pay attention to.

Attractive (compared to unattractive) communicators are always more popular, considered to be more favorable conditions, and have a positive impact on the products they are associated with (Joseph, 1982). As the communicator of information, influencers have an invaluable role, and the influence of influencers on their physical attractiveness will affect their persuasiveness. Physical attractiveness is a usable resource in social influence (Mills & Aronson, 1965). Attractive speakers influence their audience through the identification process. The audience will feel like the speaker or want to be like the speaker and build a positive relationship with him / her (Kelman, 1958). The influencers are leaders in their field, who have established a high level of trust and two-way communication channels with their fans. As a result, celebrities and online influencers launch fashion and other trends that their followers admire. When the recipient sees him/her as someone they can rely on, the influencer has more influence (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). Therefore, researchers hypothesize:

H3: There will be a significant and positive relationship between physical attractiveness and purchase intention.

Parasocial Interaction Theory

Parasocial interaction (PSI) theory began in the 1950’s from communication literature/research and was created to develop an explanation of the relationships that were forming between consumers and television and radio (Horton & Wohl, 1956). PSI is defined as

“An illusionary experience, such that consumers interact with personas (i.e. mediated representations of presenters, celebrities, or characters) as if they are present and engage in a reciprocal relationship” (Labrecque, 2014).

This is relevant to the topic of celebrity influencers and brands as friends on social media platforms such as Instagram. Many researchers argue that PSI can arise from one initial reaction, isolated reactions, to even long periods of relationship building (Perse & Rubin, 1989; Hartman & Goldhoorn, 2011). PSI can be mediated through a person (in this study’s case a celebrity) or also through design and the presentation of information (the brand) (Hoerner, 1999). Labrecque (2014) makes the case that these phenomena can be developed through brands and celebrities and not just mass media.

PSI has two meanings: people react to media characters such as celebrities, actors, and presenters; and this reaction is like people are talking face-to-face with real friends (Hartmann, 2008). In fact, it means that when viewers use social media, they will have a kind of relationship with people on the screen consciously or unconsciously. The concept of PSI grew out of communications literature and offered to develop the relationship between consumers and the mass media. In the process of media consumption, the audience will naturally imagine the media characters as people who can be reached in daily life, react accordingly, and thus create an intimate connection (Horton & Wohl, 1956). Long-term PSI will form social relationships similar to those formed by people through face-to-face interactions, that is, parasocial relationships (Perse & Rubin, 1989). This relationship is often wishful thinking, although this relationship is not strongly perceived as the relationship between people in real life. But it does exist objectively. PSI can be used to describe the relationship between fans and celebrities, and long-distance one-way interactions enhance emotional dependence (Giles, 2002). PSI between celebrities and the public is divided into three levels: cognitions, emotions and behavior, which respectively correspond to the three forms of communication around the content of communication, the public and celebrity emotional exchanges, and self-internalization of the public to celebrity behavior (Klimmt et al., 2006).

At the cognitive level, the public is sensible (Perse & Rubin, 1989). They determine whether or not to conduct such behavior in the future by measuring the degree of satisfaction and the value of the content of the communication: if expectations are always realized, a habitual mode of media use is established. The primary purpose of public contact with the media is to obtain information and the position of the mass media on specific events. Celebrities are the bridge between the media and the public. Therefore, they can clearly convey information and media positions in their own way to meet the public's expectations of information. It is the basic quality of celebrities.

The purpose of the public's use of the media's emotional orientation is to satisfy their emotional needs and to have a sense of pleasure (Perse & Rubin, 1989). To a large extent, the audience has an emotional identity with the unique style of celebrities. Once this identity is generated, it is relatively stable and difficult to change. The key to the success of celebrities lies in their ability to achieve the PSI interaction of emotional level with the public (Hartmann, 2008). This kind of communication has been deepened from the previous cognition of the content of communication to the attitude of celebrities. Once formed, it will be deeply rooted in the hearts of the people. At this time, the audience's dependence on celebrities is extremely strong.

The influence of celebrities comes from the appeal of their content and the public's emotional dependence on them. In the long run, they will further influence the public's behavior and enable the public to achieve their social interactions in action (Perse & Rubin, 1989). People's social behavior is the result of observation and learning, and imitation becomes the most direct way of socialization (Bandura & Walters, 1977). This level of communication is the product of the public's emotional dependence on celebrities. At this time, the influence of celebrities has extended to the real life of the public.

Compared with celebrities, the images of influencers on social media are ordinary, approachable and authentic, which makes the audience feel more like them or close to them (Chapple & Cownie, 2017; Schouten et al., 2019). Influencers often refer to users who "follow" them on social media as "followers," rather than "fans," because the term masks a sense of status promotion and social distance between influencers and their followers (Marwick & boyd, 2011; Abidin, 2015). Online social network users can build this relationship with influencers by following their home page and following their posts on instagram. Multiple followers can form an online community in which members share similar values, beliefs and interests with influencers (Nambisan & Watt, 2011). Influencers who are able to connect with their audience are more effective at persuasion, probably because of the parasocial relationship they have with that unique influencer (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020). For example, young women follow celebrities and influencers on Instagram, which has an impact on their followers. But as followers become more connected to them, digital personalities seem more persuasive and credible (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017). Sokolova & Kefi (2020) note that PSI between Instagram influencers and their followers have a positive impact on luxury brand perceptions. Thus, leading to hypotheses 4 and 5.

H4: There will be a significant and positive relationship between PSI and purchase intention.

H5: PSI will explain the most significant addition to purchase intention above credibility, attractiveness and self-confidence.

See Figure 1 for the model of the study.

Methodology

The study was conducted using the online survey platform qualtrics. A convenience sample of students in an introductory fashion course at a large Midwestern University took part in the study. Because of this, there was an uneven balance of females to males and a younger audience of 18-20 years old which is acknowledged in the implications of this study. Participants were able to choose a pair of photographs showcasing an Instagram influencer and their original post as well as a view of the post with the tags of designer clothes worn by the influencer showing. See figure two. Participants chose one set of photos between two options for men and two options for women based on their preference. This allowed us to better understand what they deemed most interesting to them and to understand through the survey how they would directly react to a post on their own Instagram that they preferred over the other options. This was done in order to allow them to have a more authentic Instagram experience. According to Action Regulation Theory (Hacker, 1986) an individual deals consciously, planning and purposeful with his/her environment, appeals actively on the environment in this case instagram and through the choice associated not only does the environment change, but also the individual and his/her personality towards the post and shows us the holistic individual and their motive for preferences (Hacker 2005, Oesterreich, 1987, Schelten, 2002, Wiendieck,1993). They were then asked a series of questions pertaining to the post they chose related to credibility, social interaction, physical attractiveness, and self-confidence, as well as purchase intention. The most popular choice among this group was the lower right post (n= 154) followed by the lower left (n= 94) and the top right (n=27), top left (n=15). See Figure 2.

The survey consisted of 26 questions. Six questions pertaining to credibility were utilized from Lim et al. (2017), for example, “I find this influencer trustworthy”, and “I find this influencer expert in her domain.” Parasocial Interaction had 5 items from Sokolova & Kefi, (2019) and Labrecque, (2014), such as I would follow her and interact with her on other “social networking sites”, and This influencer makes me feel comfortable, as if I am with a friend. Physical attractiveness included 3 items from Sokolova & Kefi, (2019); Kahle & Homer, (1985), including “I think this influencer is pretty.” Self-confidence came from Jain et al., 2014; Shim et al., (1991) had 3 items including “The apparel I see in this post would bring me confidence.” and “I have the ability to choose the right apparel for myself after seeing this post.” Finally, Purchase intention from Hyllegard, Yan, Ogle & Lee, 2012; Sokolova & Kefi, 2019 had 2 items including “In the future I will intend to buy this item I see in the post.”

All items were placed on a 3 pt likert scale (1: Disagree; 2: Neutral; 3: Agree) to discourage survey fatigue. Cummins & Gullone (2002) state

“It is still true that the kinds of psychometric data researchers report in support of their scales are generally restricted to reliability (internal and test-retest) and convergent/divergent validity which is, itself, highly dependent on reliability. This narrow focus has led, inexorably, to the view that smaller, rather than larger numbers of scale points are advantageous to measurement e.g. Cronbach, (1946).”

Peabody (1962) found the directional component of the Likert scale over the intensity component and that a two-point or dichotomous agreement scale of either agree or disagree was favorable. This hypothesis was later supported by Komorita (1963), Komorita & Graham (1965), Bendig (1954), Peabody (1962), Jacoby & Matell (1971) and Matell & Jacoby (1972). There is a “relative irrelevance of additional scale choices to assess intensity” (Munshi, 2014).

Correlations and a hierarchical regression were conducted to understand the significance between variables and their relationship if any with purchase intention.

Results

A total of 304 respondents completed the online survey from a large midwestern university. A majority of the respondents were female (88.4%, n= 268) and 18 years old (66.3%, n=197). When asked about their usage of Instagram a majority of respondents indicated they access Instagram 9 or more times a day (35.9%, n=109). The most popular Instagram influencer they followed was Kylie Jenner and Kim Kardashian (with many indicating they followed the entire family also), Zendaya, Jeffrey Star, Emma Chamberlin, Bella Hadid, Rihanna, Aimee Song, and Tezza, proving that celebrity is still a possible influential component on social media for this generation. See Table 1 for the full breakdown of the demographics of the study.

| Table 1: Demographics | ||

| Item | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male= 35 | 11.30% |

| Female= 274 | 88.40% | |

| Other= 1 | 0.30% | |

| Age (in years) | 18=204 | 65.80% |

| 19=73 | 23.60% | |

| 20=18 | 5.80% | |

| 21=4 | 1.30% | |

| 22=1 | 0.40% | |

| 23=1 | 0.40% | |

| 24=3 | 1.00% | |

| Do you consider yourself an active user of Instagram? | Yes= 277 | 89.40% |

| Maybe= 19 | 6.10% | |

| No= 14 | 4.50% | |

| How often do you access Instagram per day? | 0-2 times=16 | 5.20% |

| 3-5 times=67 | 21.60% | |

| 6-8 times=100 | 32.30% | |

| More than 9 times= 109 | 35.20% | |

| Do you follow the hashtag #OOTD? | Yes=203 | 76.70% |

| No=61 | 23.00% | |

| Do you follow Fashion Influencers on Instagram? | AR=46 | 17.40% |

| VR=93 | 35.10% | |

| Both=125 | 47.20% | |

All scales were found reliable with Cronbach’s Alpha >.7. Correlations were conducted to determine the individual relationships between the variables and a hierarchical regression was conducted to determine the strongest contributing factor to purchase intention from an #ootd post by an instagram influencer. All correlations between variables were found highly significant at p=0.000 level except for purchase intention and physical attractiveness but that was still found to be significant (p=0.021). This could be less notable as the participants selected the pair of photographs leading to physical attractiveness bias. There was no presence of multicollinearity found leading us to the hierarchical regression. It was found that 46.2% of purchase intention variation was explained by credibility, PSI, physical attractiveness, and confidence (R=0.462) with the strongest contributing factor being PSI (B=0.314, sig.=0.000) followed by Confidence (B=0.273, sig. =0.000). H1, H2, and H4 were all accepted with H3 being rejected as it was not significant. H5 was rejected as credibility served to be the main contributor to purchase intention ovr PSI, Self-confidence and attractiveness. See Table 2.

| Table 2: Findings | ||||||

| Variable | R2 | R2 Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credibility | 0.046 | 0.046 | 13.756 | 1 | 284 | 0.000* |

| PSI | 0.158 | 0.111 | 37.413 | 1 | 283 | 0.000* |

| Physical Attractiveness | 0.158 | 0 | 0.021 | 1 | 282 | 0.886 |

| Self Confidence | 0.213 | 0.056 | 19.873 | 1 | 281 | 0.000* |

*= p<0.001

Discussion and Implications