Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 4

How Social Media Communications can Mitigate Negative Impacts of Corporate Social Irresponsibility on Corporate Financial Performance?

Saad A. Alhoqail, Alfaisal University

Hyun Young Cho, Dongguk University

Kristopher Floyed, Chapman University

Abstract

Previous research on corporate social responsibility (CSR) has focused on corporate reputation (CR) and corporate financial performance (CFP), showing a high correlation between both. While most researchers primarily focus on CSR, our research examines the other side of the coin; corporate social irresponsibility (CSI) and provides findings that counter previous thought. We contribute to the existing literature by showing that CSI has a non-significant impact on corporate financial performance, as measured by market value, while concurrently being negatively correlated to corporate reputation. Further, we show social media, as measured by the Social Media Sustainability Index (SMSI), a measure studied infrequently thus far in the literature, mediates the relationship between CSI and market value. This relationship between social media and financial performance is further strengthened when companies actively engage in other CSR activities that “fit” their image. From a practical standpoint, when companies “misbehave” our research reveals how to mitigate those effects in regards to financial performance.

Keywords

CSI, Corporate Reputation, Market Value, Social Media, CSR fit, Environment.

Introduction

Research suggests that when companies behave in a socially irresponsible manner, consequences will follow (Scott, 2008). Further, research by Fombrun (1996) suggests that what follow is not only losing current customers, but the inability to attract new customers as well. This is important because research implies that when consumers are faced with negative, as opposed to positive events, they will spend more time in deliberation, searching for information and resorting to more extreme measures in response to such news (Fiske & Taylor, 2008). This would then indicate that corporate social irresponsibility (CSI) would loom larger than corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Muller & Kräussl, 2011). However, this research asserts this is not always the case. Consider the case of CSR, although much research has shown it to be an effective tool for increasing the bottom line (Robert & Dowling, 2002; Eberl & Schwaiger, 2005). Authors intimate that very few people know or even care about CSR and that, as always, the basis of most products purchases is quality or price. Yet, many companies continue to increase their CSR programs and reach (Vogel, 2008). The possibility then exists that under the certain circumstances, companies can “misbehave” and suffer few, if any consequences. As such, this research concurrently examines the influence of CSI on both corporate financial performance (CFP) and corporate reputation (CR) in an order to show that instances of when and how CSI may be of importance and when and why it may be inconsequential.

Gap

Maignan & Ferrell (2004) were one of the first to propose the importance of social responsibility to both the organization and its stakeholders. In conjunction with their framework, much prior research (e.g., Robert & Dowling, 2002; Eberl & Schwaiger, 2005) has shown positive relationship between CR and CFP, with stakeholder theory (Donaldson & Preston, 1995) being the foundation of many of these studies. Nikolaeva & Bicho (2011) showed that when companies publicly engage in CSR activities they are more likely to adopt reporting measures that influence their reputation and CR is more than just an outcome of CSR; it is an important mechanism in the relationship between CFP and CSR (Fombrun, 1996). In spite of the abundance of research on CSR and CR, more research is required on the circumstances and pathways through which these two important firm characteristics may track in opposing directions. Furthermore, while most research thus far, has investigated CSR, few studies have investigated the impact of CSI on CFP and CR. This distinction is important and one that requires more investigation. Moreover, more investigations are needed into how social (ir) responsibility (Peloza & Shang, 2011) can establish or damage value for firms and their customers. In addition, with new social media mechanisms becoming more prominent, previous research has not explored the role social media plays in explaining CSI’s impact on CFP. In an era where social media has become widespread, understanding the conditions and boundaries, such as CSR fit, where social media’s influence on CFP will be the strongest is important.

Contribution

We contribute to the existing literature in three important ways. First, we contribute to the social responsibility literature by examining CSI’s influence on CFP and CR. CSI’s operationalization comes from the KLD database and consists of community concerns, corporate governance concerns, diversity concerns, employ relation concerns, environmental concerns, product concerns, and human rights concerns. We show that while irresponsibility may influence CR, CSI has no impact on CFP. This is an important finding for firms and managers. Next, we contribute to the social media literature by revealing that social media implementation, measured by the Social Media Sustainability Index (SMSI), partially mediates the relationship between CSI and CFP. This index is relatively new and studying its impact is important in the CSR/CSI domain. Finally, we contribute to the social responsibility literature by showing an important boundary condition in this relationship; when current CSR activities “fit” the company, this “fit” fortifies SMSI’s influence on CFP.

Conceptual Framework

Corporate Reputation

Research has shown that a good corporate reputation can provide strategic value for the firm (Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Rumelt, 1987; Weigelt & Camerer, 1988). A resource view of the firm would see CR as an asset that is valuable and difficult to imitate. When a firm has assets that are difficult to imitate, they can achieve not only superior returns but also sustain it longer as well (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991). This reasoning seems to suggest that inherit to sustainable performance is CR. Past researchers define CR as action and future prospects that reveal how appealing a firm is to its key constituents (Fombrun, 1996). CR is formed from past actions of managers (Podolny & Phillips, 1996). In many instances, external forces determine these actions and this leads managers to engage in such actions in an effort to build and sustain their CR (Fombrun, 1996). However, external constituents cannot always observe all action taken by managers to derive a good reputation, thus, in many cases; they rely on heuristic cues in the environment to signal the firm’s overall intangible value (Roberts & Dowling, 2002). When consumers have knowledge about companies, they give greater importance to ethical behavior (Singh et al., 2008). Companies that claim high CSR behavior are perceived as such, but unethical behavior will harm their reputation (Swaen & Vanhamme, 2005).

Corporate Financial Performance and Corporate Social (Ir) Responsibility

Consumers view companies that engage in CSR more favorably (Simmons & Beck-Olsen, 2006). Research has shown that a strong record in corporate social responsibility can enhance a firm and its brands (Holt et al., 2004). This has led to previous findings that CSR is positively associated with CFP (e.g., Orlitzky et al., 2003). However, in many previous studies, we still do not know how CSI affects these two constructs, as investigations into CSI are scarce. Further, consumers purchase products based on quality and price and some research has shown that few people know or care about CSR (Vogel, 2008). This is because product quality influences customer loyalty and brand equity Vogel et al. (2008) and quality matters to consumers. The quality of the products and the accurate delivery of the service are important factors that ultimately lead to CFP Vogel et al., (2008), even in the absence of any real CSR program (Vogel 2008). The problem is that this mindset leads consumers to view companies as competent, which can lead to profitability, yet devoid of warmth (Aaker et al., 2010).

Hypotheses Development

Corporate Social Irresponsibility, Corporate Financial Performance and Corporate Reputation

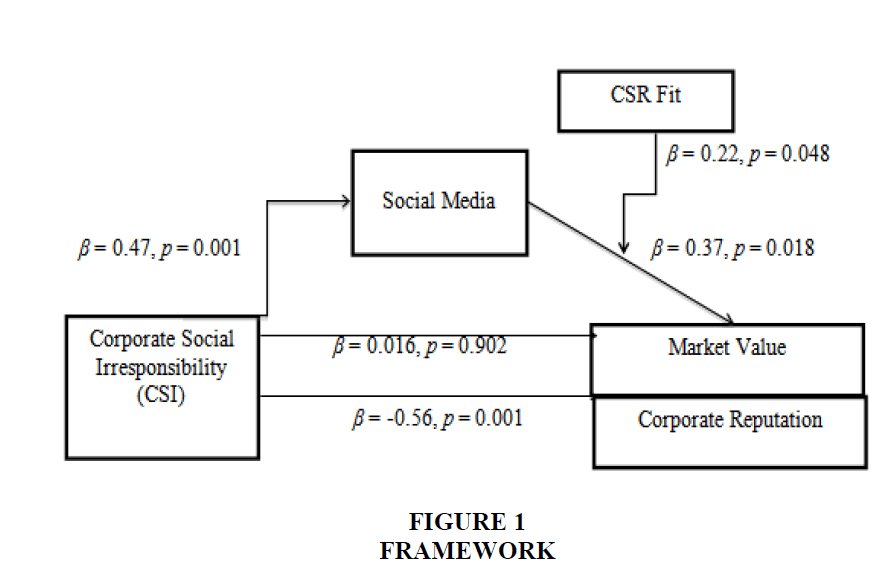

We contend that while CSI will have no influence on CFP (Market Value), CSI will negatively influence CR. Figure 1 conceptualizes how the components operate concordantly. While focusing on profits creates a loss of sympathy in the mind of consumers, focusing on responsibility dampens quality, attractiveness and performance (Schwaiger, 2004). Product quality, attractiveness, and company performance are concrete capabilities that may be easier for a consumer to experience. Conversely, sympathy, responsibility, and attractiveness, more abstract concepts, may require consumers to find cues in the environment in order to evaluate these concepts. This implies that consumers may evaluate products based on quality, price and competence of the company, which suggests ignoring negative components of CSI. On the other hand, CSI or CSR may lead to emotional responses in the consumer, acting as cues about a company and thus, the consumer’s perceptions may subsequently affect CR.

H1: CSI will have no impact on CFP (market value).

H2: CSI will be negatively related to CR.

Mediation

We suggest social media is an underlying mechanism that prevents CSI from having detrimental impact on firms’ market value. There are two reasons. First, when firms talk a lot about CSR through social media, consumers may be less aware of actual CSI. According to Andriof & Waddock (2002), when firms communicate with their customers through social media, customers feel that they are operating in transparent way by creating “mutually engaged” relationships. Additionally, social media appears to be an indirect tool of communication that requires consumer to “buy-in” (i.e., actively searching for the information through firms’ website). In this sense, consumers may feel that they are closely engaged in firms’ activities and such a feeling may lead them to believe they are well aware about what is actually going on in a firm. This makes sense as previous research Vlachos et al. (2009) has shown that consumer trust is an important mediator between firm CSR and purchase intentions. Thus, as social media, through transparency, increases consumers’ belief that a firm is doing the right thing, they may be less likely to seek out information about actual CSI. Moreover, social media may cause consumers to become overly trusting. Previous studies have shown that communicating CSR messages can facilitate positive reactions from stakeholders, including customers (Morsing & Schultz, 2006). As communication between firms and customer increases, customers will increase loyalty to the firm and this increase in loyalty will likely lead to greater financial performance. Logically, at this point in the relationship, customers are less likely to care about actual CSI. The implication then becomes that social media can attenuate the negative impact of CSI on market value.

H3: The relationship between CSI and market value will be at least indirectly mediated by SMSI.

Boundary Conditions

Fit

We believe the fit of the company’s current CSR activities will moderate the relationship between SMSI and CFP. A company may concurrently be both responsible in one area, while also being irresponsible in another. If this is the case, social media may influence consumers’ to pay even less attention to any irresponsibility that may plague a company. This will especially be true when there exist a match between the responsible actions of the company and the company itself. Findings that may be applicable to this research are those from the brand extension literature. Völckner & Sattler (2006) found that when a parent company extended a brand in a way that fit their current products, the success of the product was greater. This is because things that “fit” are familiar to consumers and increase product success. Similarly, in terms of CSR fit, we believe that when CSR fits a company’s image and product, customers will be more likely to familiarize themselves with this initiative furthering the likelihood of ignoring CSI. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis.

H4: The fit of current CSR activity will moderate the relationship between SMSI and CFP (Market Value), such that when fit is greater; SMSI will have a stronger impact on CFP (Market Value).

Methodology

Data Collection

Key measures

Table 1 shows each variable, measure, and source of data.

| Table 1: Variables, Measures And Data Sources | ||

| Variables | Measures | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| CSI | A firm’s rank in terms of weaknesses in regards to social responsibility. | KLD |

| Corporate Reputation | Firm reputation is ranked based on firm’s gross revenue after Fortune magazine’s adjustments that exclude the impact of excise taxes companies incur. | Fortune 500 |

| Market Value | Variable ‘MKVALT’ in COMPUSTAT | COMPUSTAT |

| SMSI | This index measures the extent to which the firms are using social media to tell their sustainability effort. | Report by Yeomans, (2012) |

| CSR Fit | An indication of whether a firm’s CSR activities match its strategic objectives or business domain | Firm website |

| Firm Size | Variable EMP that indicates the number of employees in the firm. | COMPUSTAT |

| Dividend Pay | The ratio of cash dividend to market value. | COMPUSTAT |

| Firm leverage | The ratio long-term debt to total assets | COMPUSTAT |

| Return on Assets (ROA) | The ratio of a firm’s operating income to its book value of total assets | COMPUSTAT |

| Return on Sale (ROS) | The ratio of a firm’s operating income to its total sales | COMPUSTAT |

| Firm advertising | The ratio of advertising expenses to total assets | COMPUSTAT |

| R&D investment | The ratio of R&D expenses to sales | COMPUSTAT |

| Manufacturing industries | A dummy variable for goods industries versus services ones | COMPUSTAT |

Table 1 shows each variable, measure, and source of data.

Corporate social irresponsibility

CSI includes data for three successive years that are collected from KLD. We selected seven common dimensions that previous literature has used to conceptualize CSR to make a composite score by averaging them together. Dimensions include community concerns, corporate governance concerns, diversity concerns, employ relation concerns, environmental concerns, product concerns, and human rights concerns.

Corporate reputation

Firm reputation scores were obtained from Fortune 500. Firm reputation is based on the firm’s gross revenue after Fortune magazine’s adjustments that exclude the impact of excise taxes companies incur.

Market value

Market values were obtained from COMPUSTAT. Market value accounts for both stock price and stock quantity and is a well-known measure of company value that has been used previously in the literature. By using market value as our key indicator of CFP, we are fully able to capture the companies’ value across multiple shareholder groups.

Social media sustainability index

We utilized the SMSI rankings for a hundred companies that are in the SMSI report. SMSI index were compiled through several steps. First, leading sustainable company lists were scanned including Corporate Knights Global 100, Newsweek’s Green Rankings, The Dow Jones Sustainability Index and Interbrand’s Best Global Green Brands. Initial scanning generated around 400 companies. Next, around 250 companies among them were found to communicate sustainability through social media. Then those companies were examined as to whether they publish a Facebook page, Twitter account, or YouTube channel in order to communicate sustainability issue with publics. 108 companies were identified. Finally, the top 100 companies were chosen based on specific scoring categories – useful communication, commitment to community, transparency (allowing comments and replying), communicating actions not beliefs, social media shareable CR/Sustainability report, regular updates of social media communication, and creative storytelling. Each company’s SMSI scores were calculated based on those categories and top 100 companies were selected.

Fit

To examine the influence of CSR fit, independent coders (PhD students) visited each page to discover current CSR activities. Coders then rated the fit of each activity, disagreements were handled through discussion and rater agreement was 98 percent.

Control variables

We controlled for a comprehensive set of firm and industry-level factors. These controls closely follow previous literature that has examined CSR and marketing variables (Luo & Bhattacharya, 2006). All control variables were obtained from COMPUSTAT.

Firm size

Indicates the total number of employees was selected to measure the firm size. Previous research has shown that firm size can affect firm’s financial performance and innovation (Gatignon & Xuereb, 1997).

Dividend pay

Dividend pay is ratio of cash dividends to market value. This variable is controlled because dividends are the portion of corporate profits paid out to stockholders. Higher dividend is related to higher profits and such higher profits may lead to better corporate reputation or market value.

Firm leverage

This is the ratio of long-term debt to total assets. We measure this variable because firms that acquire more leverage often have increases in market value.

Firm advertising

We measure the firm’s advertising expenditures as the expenses from advertising divided by revenue. Prior studies McAlister et al. (2007) have found that firm advertising influences market value and systematic risk and return.

R &D investment

We also measure R & D investment. Following prior literature (Luo & Homburg 2007), this is calculated as R & D expense divided by sales. Previous research has shown that R & D investments can influence risk and return, which subsequently affects market value.

Return on assets (ROA)

Measured as the ratio of a firm’s operating income to its book value of total assets.

Return on sale (ROS)

Measured as the ratio of a firm’s operating income to its total sales

Hypotheses Testing: Analysis And Results

Analysis Approach

Analysis was completed via a stepwise regression analysis. Our independent variable is CSI and dependent variables are firm reputation and market value. First, we regressed the impact of CSI on market value and firm reputation, then we added our control variables, and we tested mediating effect of SMSI rankings following suggestion of (Zhao et al., 2010). Finally we tested moderated effect of both fit and industry type.

Results

Our results confirm hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2, CSI is not significantly related to market value. However, CSI is negatively and significantly related to corporate reputation.

Market value as predicted, CSI did not have significant impact on market value ( β = 0.016, p=0.902). CSI do not appear to harm firm’s financial performance in the market.

Corporate reputation supporting our hypothesis, CSI negatively influenced corporate reputation ( β = -0.56, p =0.001). Although firms’ corporate reputation is reduced by CSI, market value appears to be intact regardless of negative CSI. Our data supports our argument that corporate reputation and market value is not always track in the same direction. In fact, they can travel in opposite directions (Table 2).

| Table 2: Impact Of Csi On Market Value And Corporate Reputation | ||

| Dependent Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Market Value | Corporate Reputation | |

| Control Variables | ||

| Firm Size | 0.50*** | 0.65*** |

| Firm leverage | -0.18 | -0.30 |

| Firm advertising | 0.15 | 0.26 |

| R&D investment | -0.06 | -0.11 |

| Return on Investment (ROI) | -0.34** | -0.16 |

| Return on Sale (ROS) | 0.01*** | 0.65** |

| Key Variables | ||

| CSI | 0.016 | -0.56*** |

| Fit | -0.136 | -- |

** p < .05

Mediation

We argue that active communication through social media with customers will reduce negative impact of CSI on market value. Since our hypothesis predicts ‘non significant’ relationship between two variables, following Zhao et al. (2010) appears to be appropriate approach to test the mediation effect of social media usage. They argued that in order for an effect to be mediated, a significant direct effect was not necessary. They identified several patterns of mediation and one of the patterns matches our hypothesis – indirect-only mediation. This pattern indicates a situation where mediated effect exists, while direct effect does not. In order to have indirect-only mediation, both paths from CSI to SMSI score and SMSI score to market value should be significant. CSI are significantly related to SMSI score ( β=0.47, p = 0.001) and SMSI score has positive impact on market value ( β =0.37, p=0.018). Thus, the extent to which firms utilize social media to communicate with customers is a possible mechanism that protects market value from negative CSI.

Moderation

After controlling for independent variables and control variables, we find a significant interaction effect between SMSI and fit ( β = 0.22, p =0.048). The positive impact of SMSI on market value is larger when a firm’s current CSR activities fit its strategic objectives than when they do not fit its strategic objectives. Next, we examined our hypothesis that usage of social media is the mechanism that inhibits CSI from compromising firms’ market value Table 3 and Table 4.

| Table 3: Mediation & Moderating Effect Of Social Media And Csr Fit | ||

| Dependent Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Market Value | SMSI scores | |

| Control Variables | ||

| Firm Size | 0.012 | 0.09 |

| Firm leverage | -0.32 | 0.02 |

| Firm advertising | -0.14 | -0.14 |

| ROI | -0.36 | 0.69** |

| ROS | 0.82** | -0.47 |

| Manufacturing industries | -0.05 | -0.14 |

| Dividend | 0.30 | |

| Key Variables | ||

| CSI | 0.016 | 0.47** |

| SMSI scores | 0.37** | |

| SMSI score x CSR Fit | 0.227** | -- |

**p<0.0.

| Table 4:Means, Standard Deviations And Correlations | ||||||||||||||||

| Correlations | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | St.Dev | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| 1. HOPE7 | 0.7 | 0.45 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2. Reputation Score | 6.7 | 0.95 | -0.126 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 3. Market Value | 54553.03 | 61496 | 0.362** | 0.331** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 4. Inverse SMSI Rank | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.549** | -0.014 | 0.389** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 5. Fit (1) not fit (2) | 1.2 | 0.4 | -0.02 | 0.286** | 0.212* | -0.048 | 1 | |||||||||

| 6. Size | 20154.4 | 182530.7 | -0.108 | 0.152 | -0.07 | -0.048 | 0.232* | 1 | ||||||||

| 7. Dividend Pay | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.033 | -0.113 | 0.125 | 0.046 | 0.079 | -0.125 | 1 | |||||||

| 8. Leverage | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.212* | -0.466** | -0.206 | 0.279* | -0.171 | 0.2 | 0.432** | 1 | ||||||

| 9. Profitability | 0.06 | 0.07 | -0.012 | 0.432** | 0.382** | 0.016 | 0.129 | -0.264* | -0.11 | -0.355** | 1 | |||||

| 10. ROS | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.091 | 0.377** | 0.583** | 0.084 | 0.033 | -0.300** | -0.008 | -0.341** | 0.830** | 1 | ||||

| 11. ROI | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.311** | 0.323** | 0.094 | -0.049 | -0.279* | -0.211 | -0.354** | 0.904** | 0.795** | 1 | |||

| 12. Firm Advertising | 0.03 | 0.03 | -0.178 | 0.283* | -0.168 | -0.096 | 0.264* | -0.027 | -0.029 | -0.117 | 0.273* | 0.007 | 0.156 | 1 | ||

| 13. Firm R&D | 0.06 | 0.07 | -0.456** | -0.233 | -0.161 | -0.218 | -0.097 | -0.357 | -0.031 | 0.25 | -0.300* | -0.103 | -0.252 | -0.469** | 1 | |

| 14. Product (1) vs. service (2) | 1.28 | 0.44 | -0.041 | -0.089 | -0.231* | -0.19 | 0.011 | 0.173 | 0.08 | -0.048 | -0.353** | -0.360** | -0.308** | -0.184 | 0.11 | 1 |

| **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed) | ||||||||||||||||

| * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed) | ||||||||||||||||

Discussion

Overall, our results provide evidence that market value and corporate reputation do not always travel in the same direction in regards to CSI. More specifically, we show that in regards to CSI; concerns related specifically to community, humanitarian and the environment factors have a negative impact on corporate reputation. Conversely, they have no impact on market value and the SMSI score indirectly mediated the effect. Further, the influence of social media on market value is strengthened when CSR initiatives fit the company and product. The results add to the literature because they are in stark contrast with past literature that has intimated that corporate reputation and corporate financial performance are correlated. One reason why previous literature may have not discovered these results may be the model and variables utilized by past researchers. In most previous instances, corporate financial performance and corporate reputation were examined as predictors of one another with only CSR as the independent variable.

Theoretical Contributions

We contribute to the literature in three very important ways. First, we contribute to the social (ir) responsibility and financial performance literature by revealing that when companies misbehave, their actions may go unnoticed in one realm, while still influencing another. Fombrun & Shanley (1990) found that the public uses signals from the financial environment to establish the reputation of the company in their mind. Our findings suggest that financial aspects and corporate reputation actually can hold different places concordantly in the consumer’s mind and it can be that CSI acts as a cue in the environment by signaling where to process these indicators in the mind of the consumer. Second, we contribute to the social media literature showing the importance of social media in regards to CSR/CSI and financial performance. This is a new pathway that has not been investigated often and an important route that may influence financial performance. Finally, we are able to show boundary conditions that further strengthen the relationship between SMSI and CFP.

Implications

For managers, the implication becomes that while talking about what you are doing right may help or at least not hurt your corporate financial performance, “misbehaving” can influence corporate reputation. Even though we did not test here, this implies the possibility that there may be dire consequences in terms of long-term effects of ignoring CSI in regards to corporate financial performance. Although our research shows that in the short-term, the effects are minimal, the long-term effects could be much more detrimental. Further, managers must be cognizant of the kind social initiatives they are involved in as fit is important. Finally, utilizing social media as a tool for interacting with consumers and alerting them to responsible initiatives is a way to mitigate any harmful effects of CSI.

Conclusion

Limitations and Future Research

We are limited by our data. Because we rely on the SMSI index, a tool that has been used infrequently in data analysis to date, we can only analyze three years of data. This means the long-term effects are still unknown and need to be investigated further. This also implies that further research is needed using the SMSI index to qualify its results and scores. Also, based on the findings of this paper, it is possible that other mediators exist that may yield similar results. Future research needs to investigate whether other pathways exist that may lead to diverging outcomes of CSR on corporate financial performance and corporate reputation. Finally, it is very likely that other interesting moderators exist in this relationship. It would behoove future researchers to take this research and step further in order to discover them.

In conclusion, CFP is protected from CSI via the social media. However, CR is not so lucky, CSI will influence corporate reputation as our results from this study confirm.

Case Study-Ford Motor Company

In 2009, at the height of the economic crisis, Ford Motor Company was the only American car company who did not receive a bailout from the United States Government. Further, in the previous three years, the market value of Ford had continued to increase, and in 2010 and 2011 they were the third ranked company in our SMSI index. Despite the positive metrics, they still hold one of the lower reputation scores of the companies in our data, and based on the KLD index have one of the largest scores in regards to CSI. Ford Motor Company epitomizes the notion that while CSI may not impact financial performance, they may well be associated with lower corporate reputation scores. As our theory suggests, social media presence in regards to CSR is well suited to explain these diverse findings. Additionally, we find that Ford Motor Company also works hard to maintain CSR projects, such as those in regards to material use that “fit” the company and its image. The possible takeaway for managers is that by doing good things, and reporting good things, the detriments of CSI can be mitigated.

References

- Aaker, J., Vohs, K.D., & Mogilner, C. (2010). Nonprofits are seen as warm and for‐profits as competent: Firm stereotypes matter. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 224-237.

- Andriof, J., & Waddock, S. (2002). Unfolding stakeholder engagement. In J.S. Andriof, B.H. Waddock & S.S. Rahman (Eds.), Unfolding Stakeholder Thinking: Theory, Responsibility and Engagement, 19-42. Sheffield: Greenleaf.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35(12), 1504-1511.

- Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. (1995). The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence and Implications? Academy of Management Review, 29(1), 65-91.

- Eberl, M., & Schwaiger, M. (2005). Corporate reputation: Disentangling the effects on financial performance. European Journal of Marketing, 39(7/8), 838-854.

- Fiske, S.T., & Taylor, S.E. (2008). Social cognition: From brains to culture. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Fombrun, C.J. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name?: Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy Of Management Journal, 33(2), 233-258.

- Gatignon, H., & Xuereb J. (1997). Strategic orientation of the firm and new product performance. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(1), 77-90.

- Grant, R.M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114-135.

- Holt, D.B., Quelch, J.A., & Taylor, E.L. (2004). How global brands compete. Harvard Business Review, 82(9), 68-75.

- Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C.B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 1-18.

- Luo, X., & Homburg, C. (2007). Neglected outcomes of customer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 71(2), 133-149.

- Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O.C. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and marketing: an integrative framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing science, 32(1), 3-19.

- McAlister, L., Srinivasan, R., & Kim, M. (2007). Advertising, research, and systematic risk of the firm. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 35-48.

- Morsing, M., & Schultz, M. (2006). Corporate social responsibility communication: Stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 51(4), 323-338.

- Muller, A., & Kräussl, R. (2011). Doing good deeds in times of need: A strategic perspective on corporate disaster donations. Strategic Management Journal, 32(9), 911-929.

- Nikolaeva, R., & Bicho, M. (2011). The role of institutional and reputational factors in the voluntary adoption of corporate social responsibility reporting standards. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 136-157.

- Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F.L., & Rynes, S.L. (2003). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403-441.

- Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 117-135.

- Podolny, J.M., & Phillips, D.J. (1996). The dynamics of organizational status. Industrial and Corporate Change, 5, 453-471.

- Robert, P.W., & Dowling, G.R. (2002). Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23(September), 1077-1093.

- Rumelt, R.P. (1987). Theory, strategy, and entrepreneurship. In D. Teece (Ed.), The Competitive Challenge, 137-158. Ballinger, Cambridge, MA.

- Schwaiger, M. (2004). Components and parameters of corporate reputation-An empirical study. Schmalenbach Business Review, 56, 46-71.

- Scott, W.R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas andinterests (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Simmons, C.J., & Becker-Olsen, K.L. (2006). Achieving marketing objectives through social sponsorships. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 154-169.

- Singh, J., Salmones, S., & Bosque, I. (2008). Understanding corporate social responsibility and product perceptions in consumer markets: A cross-cultural evaluation. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(3), 597-611.

- Swaen, V., & Vanhamme, J. (2005). The use of corporate social responsibility arguments in communication campaigns: Does source credibility matter? Advances in Consumer Research, 32(1), 590-591.

- Vlachos, P.A., Tsamakos, A., Vrechopoulos, A., & Avramidis, P. (2009). Corporate social responsibility: Attributions, loyalty and the mediating role of trust. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(2), 170-180.

- Vogel, D. (2008). CSR doesn’t pay. Retrieved April 25, 2012 from http://www.forbes.com/2008/10/16/csr-doesnt-pay-lead-corprespons08-cx_dv_1016vogel.html.

- Vogel, V., Heiner, E., & Ramaseshan, B. (2008). Customer equity drivers and future sales. Journal of Marketing, 72(6), 98-108.

- Völckner, F., & Sattler, H. (2006). Drivers of brand extension success. Journal of Marketing, 70(April), 18-34.

- Weigelt, K., & Camerer, C. (1988). Reputation and corporate strategy: A review of recent theory and applications. Strategic Management Journal, 9(5), 443-454.

- Yeomans, M. (2012). Social medial sustainability index. SMI-Wizness.

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J.G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197-206.