Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 1

How the Hiring of Stigmatized Populations can Lead to a CSR Backfire Effect

Jingzhi Shang, Thompson Rivers University

Todd Green, Brock University

Abstract

Previous research shows that consumer attitudes toward Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) are equivocal. In some cases, CSR can even backfire and hurt the company. In the current research, we investigate the backfire effect of CSR by examining consumer responses to the hiring of stigmatized populations. Although it has becoming increasingly common for companies to hire stigmatized populations, our research reveals that this socially responsible practice does not bring desired consumer responses beyond a good CSR reputation. The results of three experiments show that the products produced by stigmatized populations induce feelings of disgust, which lead to lower product evaluations and lower purchase intentions. Moreover, it shows that visualization is not necessary to induce this negative effect and that this negative effect still exists when consumers are not the users of the products. However, this phenomenon has a boundary condition - the backfire effect is attenuated when consumers have a low degree of physical contact with the products.

Keywords

Corporate Social Responsibility, Stigmatized Populations, Contagion, Disgust.

Introduction

Companies engage in CSR in the hope of generating positive consumer responses such as increasing purchase intentions (Pérez et al., 2019); enhancing brand loyalty (Han et al., 2019) and increasing willingness to pay a premium price (Lerro et al., 2018). However, previous research reveals that CSR activities are not always effective in generating the desired consumer responses. In some cases, CSR activities can even backfire and hurt the company. For example, consumers are less likely to choose a new brand when its products are linked to a CSR practice than when they are not because CSR negatively influences perceived product performance (Robinson & Wood, 2018). Researchers have also identified a perceived conflict between ethical attributes and valued attributes. For instance, consumers do not believe sustainable products perform well on strength and durability because they perceive that social and environmental attributes can add a quality of gentleness and purity to a product (Luchs et al., 2010). Similarly, the strength of ethical claims negatively affects sophisticated products’ evaluations (e.g., cola and energy water) by reducing the perceived product enjoyment (Herédia-Colaço & Coelho do Vale, 2018). As these studies demonstrate, CSR backfires when CSR activities leads to more negative consumer responses than would have been the case without CSR activities (Yoon et al., 2006). The current research further examines the backfire effect of CSR by using the hiring of stigmatized populations as the focal CSR activity. This CSR activity is ideal for studying the backfire effect of CSR because it is a common practice and widespread across an array of product categories.

Governments and companies support stigmatized populations in various ways. Cisco found homes for 100,000 homeless people in the United States by 2014 (Russo, 2014). Canada is building an Inclusive Health System to better serve stigmatized populations such as First Nations, Caribbean, seniors, and LGBTQ2+ people as well as persons with health conditions, such as mental illness, substance use disorders, and HIV (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019). Since there is a lot of discrimination against stigmatized populations in the workplace, more and more companies are willing to provide job opportunities to stigmatized populations as part of their inclusion strategy (Mullaney, 2019). For example, Greyston Bakery, based out of New York, not only accepts people off the streets but also creates job opportunities for any individuals who face barriers to employment without asking them any questions or making any judgements (York Project, 2018). Uber offered former prostitutes and low-level, non-violent offenders the opportunity to drive in select states in the United States (Farberov, 2016). Timpson (Timpson Foundation, n.d.), a service retailer in the UK, has a program that trains and employs ex-offenders. It is now one of the largest employers of ex-offenders in the UK. The Japanese mobile gaming company Gree hires people with mental disability to perform simple tasks such as shredding papers (Inagaki, 2018). Hiring stigmatized populations provides a stigmatized person not only financial support but also an opportunity to get back into the society. In some cases, having a job can even help a stigmatized person get rid of the stigma.

Governments also encourage companies to hire stigmatized populations through incentive programs. For example, the U.S. Department of Labor offers the Work Opportunity Tax Credit to companies that hire groups such as veterans and ex-felon who have consistently faced significant barriers to employment (IRS, n.d.). The Chinese government not only offers tax incentives for hiring disabled staff but also has set a minimum quota for the number of disabled employees that a company must hire (USCBC, 2016). Moreover, this hiring practice can help create a good CSR reputation since workplace diversity and human rights are considered as two basic indicators of corporate social performance (e.g., KLD Research and Analytics). Because CSR that creates positive social impact has the potential to create long term advantage for firms (Porter & Kramer, 2006), such hiring practice represents, in theory, a perfect blend of social and economic objectives espoused by CSR proponents. However, using the law of contagion as a lens for viewing this CSR activity, we find that hiring stigmatized populations may not bring the desired positive outcomes but instead backfire and lead to negative consumer responses.

Literature Review

Stigmatized Populations

According to Goffman (1963), stigma is a deeply discrediting attribute which challenges a person’s integrity and reduces the person from a whole and usual person to a “deviant, flawed, limited, spoiled, or generally undesirable” one (Weiner et al., 1988, p. 738). A person is stigmatized when the person possesses or is believed to possess an attribute or characteristic that conveys a devalued social identity in a particular social context (Crocker et al., 1998). The homeless, the unemployed, ex-convicts, drug addicts, the handicapped, LGBT, and obese are all examples of stigmatized groups.

Evidence shows that stigmatized populations are discriminated in the workplace are relatively disadvantaged in terms of both economic and interpersonal outcomes (Crocker et al., 1991). For example, hiring managers perceive that the stigmatized people such as tattooed people (Timming et al., 2017) people with disabilities (Hoque et al., 2018) and members of LGBTQ (Bell et al., 2011) are less employable than the non-stigmatized when they apply for customer-facing positions. In the film industry, for instance, women only make an average of 78% of their male counterparts (Berg, 2015). The issue is even worse for women of color – African American women, Native American women, and Hispanic women make 64%, 59%, and 56%, respectively, of white men. Also, in the United States, weight stigma has a significant negative effect on wages for White women but not it does not have an impact on males or Black and Hispanic minorities (Moro et al., 2019).

Moreover, research shows that consumers hold such prejudicial attitudes as well. They are less satisfied with the tattooed service providers and less likely to recommend them to others because they view tattooed people as less intelligent and less honest (Dean, 2010, 2011). Physicians with facial piercing are rated as less competent and less trustworthy by patients and colleagues (Newman et al., 2005). Consumers even perceive poorer store image and less successful store management if the store hires obese salespersons (Klassen et al., 1996). Cowart & Brady's (2014) research shows that when the retail store does not have an excellent environment (e.g., disorganized displays, long waiting lines), consumers negatively evaluate service transactions if the frontline worker is obese compared to average weight. However, although previous research has examined consumer responses to stigmatized populations such as service providers, little is known about whether consumers hold the prejudicial attitudes toward the products produced by stigmatized populations, especially when consumers do not actually see the production process.

The Law of Contagion

The laws of sympathetic magic are widespread in both primitive and advanced societies and can influence people’s principles of thinking (Frazer, 1890, 1959; Mauss, 1902, 1972; Tylor, 1871, 1974). One of the central laws of sympathetic magic is the law of contagion, which holds that when a source and a recipient come into direct or indirect contact with each other, the source can influence the recipient by transferring its properties to the recipient (Nemeroff & Rozin, 1994). This is a permanent influence because the transferred properties are perceived to still exist in the recipient even after the physical contact has ended. Transferable properties can be either physical or moral, and also can be harmful or beneficial. Thus, the nature of transferred properties determines the consequence of contagion. Namely, positive contagion increases the value of the recipient, whereas negative contagion decreases the value of the recipient (Rozin et al., 1986).

Contagion belief is originated from physiology but it has also been found in object domain and interpersonal domain in which real contamination does not occur (Rozin et al., 1986; Steim & Nemeroff, 1995). In marketing, the law of contagion has been applied to understand different types of contagion events. For example, the value of the product would increase if it has been owned by a celebrity (Newman et al., 2011) or touched by an attractive shopper (Argo et al., 2008). However, research on consumer contagion suggests that consumers generally evaluate a product less favorably if they believe the product has been touched by others (Argo et al., 2006; White et al., 2016). It even occurs when products are objectively unharmed and when consumers do not actually see the contact. Morales & Fitzsimons (2007) study product contagion and find that a disgusting product (e.g., feminine napkins) can “pollute” a neutral product (e.g., breakfast cereal) through physical contact even though both are in a sealed package. Further, Lin & Shih (2016) further contribute to the literature by identifying factors (i.e., mood states, product-related information, package type) that moderate the product contagion effect. Extending previous research on the law of contagion, we examine the hiring of stigmatized populations as a form of producer contagion.

Negative Producer Contagion

In general terms, social stigma leads to a distinction between “us” and “them”. The “normal” people view the stigmatized as members of a marginalized out-group because the stigmatized depart largely from the society’s expectations (Goffman, 1963). As a result, the “normal” people often have prejudicial attitudes toward the stigmatized populations (Crandall et al., 2002). For example, obesity is linked with lazy, sloppy, and low in core competencies (Puhl & Heuer, 2009); tattoos are generally associated with anti-social behaviors and unhealthy traits (Timming et al., 2017); homeless people are perceived as insignificant, dishonest, irresponsible, and unintelligent (Cuddy et al., 2008).

According to the law of contagion, when stigmatized populations are hired to produce products, consumers would believe that the stigmatized can transfer their properties, immaterial qualities, and essence or soul stuff, to the products during the production process. This is a negative contagion event because the properties owned by stigmatized populations are generally viewed as negative. As a result, although hiring stigmatized populations is a socially responsible practice, it may fail to generate favorable consumer responses. Indeed, consumers will respond negatively to the “polluted” products. Therefore:

H1: Consumers perceive firms that hire stigmatized populations as more socially responsible than firms that hire non-stigmatized populations.

H2: Consumers have lower product evaluations when products are produced by stigmatized populations (versus non-stigmatized populations).

H3: Consumers have lower purchase intentions when products are produced by stigmatized populations (versus non-stigmatized populations).

H4: Product evaluation mediates the effect of producer type on purchase intention.

Feeling of Disgust as the Mediator

Disgust is defined as “a revulsion at the prospect of (oral) incorporation of an offensive substance” (Rozin et al., 1986, p. 704). It is a basic reaction people have to stigmatized populations such as the homeless (Harris & Fiske, 2007), people with AIDS (Valdiserri, 2002), and unattractive, transsexual, pierced, or obese persons (Krendl et al., 2006). Based on the nature of offensive substances, disgust induced by stigmatized populations is an example of interpersonal disgust, which is related to the prospect of contact with strangers or undesirables such as wearing a sweater owned but never worn by a disliked person (Rozin et al., 1986). Disgust is considered as a basic emotion in negative contagion events (Rozin et al., 1994) and has been identified as a key mediator in consumer contagion (Argo et al., 2006) and product contagion (Morales & Fitzsimons, 2007). Based on the above findings, we expect that consumers will experience feelings of disgust toward the products produced by stigmatized populations. Moreover, such feelings will negatively influence consumers’ product evaluations and purchase intentions.

The Degree of Physical Contact as the Moderator

Previous research has suggested that a high degree of physical contact between the source and the object can enhance contagion effects and result in more negative consumer responses to the object. In consumer contagion, researchers find that consumers have stronger feelings of disgust toward the product when they believe the product has been touched by other shoppers recently (versus a long time ago), or by many shoppers (versus only one shopper) (Argo et al., 2006). Although consumers do not actually see the contact, they make inferences about the level of contact based on different types of contamination cues. For example, superficial damage to the package (i.e., a small rip in the label) is viewed as a contamination cue suggesting that the product has been touched by others (White et al., 2016).

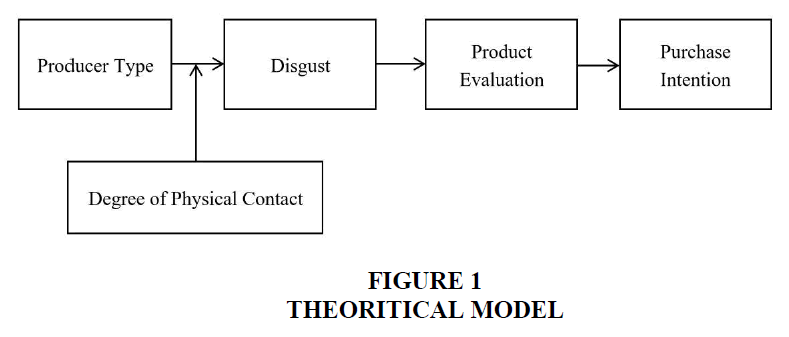

Physical proximity also impacts perceptions of contagion, and products become more contagious when they are arranged close together than apart (Mishra, 2009). Morales & Fitzsimons (2007) show that consumers’ feelings of disgust increase when the target product has physical contact (versus no physical contact) with the disgusting product. In this study, the authors find that consumers with a high (e.g., cookies) and low (e.g., notebook paper) degree of contact with the target product have similar negative responses to the target product. This finding, however, is inconsistent with Angyal’s (1941) work proposing that “the intensity of disgust increases with the degree of intimacy of contact: vicinity, contact with the skin, mouth, ingestion” (p. 394). In this study, we further examine the role of the degree of physical contact between the consumer and the product Figure 1. We expect that the effect of hiring stigmatized populations on consumer responses is moderated by the degree of intimacy of contact. Or, more formally:

H5: When consumers have a low degree of physical contact with products; producer type (stigmatized populations or non-stigmatized populations) has no impact on feelings of disgust, product evaluations, and purchase intentions.

H6: When consumers have a high degree of physical contact with products, products produced by stigmatized populations (versus non-stigmatized populations) lead to stronger feelings of disgust, lower product evaluations, and lower purchase intentions.

Methodology

Study 1

Study 1 was designed to test H1-H4. It included a pretest and a main experiment.

In order to enhance external validity, we first conducted a pretest to select a real fast-food restaurant for the experiment. 31 undergraduate students from a Canadian university (50% female) were asked to indicate their identification with and purchase intention of a list of fast-food restaurants. We adapted a four-item scale from Currás-Pérez et al., (2009) to measure identification with a brand: “The way I am fits in with what I perceive of [X],” “I am similar to how I perceive [X],” “I am similar to what I think [X] represents,” and “The image I have of [X] overlaps with my self-image” on a seven-point scale anchored at 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree) (α =0.97). Purchase intention was measured by one item from 1 = “very unlikely” to 7 = “very likely.” Among a list of fast food restaurants, Subway was chosen as the focal restaurant for the experiment because participants had a neutral identification (t-test versus the scale midpoint: M = 3.57, t(30) = -1.36, p=0.18) and neutral purchase intention (t-test versus the scale midpoint: M = 4.53, t(30) = 1.40, p=0.17).

53 undergraduate students from a Canadian university (52.5% female) took part in the main experiment which used a two-condition (Producer Type: Stigmatized versus Non-Stigmatized) between-subjects design. Two scenarios describing a Subway restaurant’s hiring practice were created (See Appendix 1 for the scenarios). Subway was described as either hiring homeless people (i.e., Stigmatized condition) or hiring employees through an employment agency (i.e., Non- Stigmatized condition). The scenarios specifically emphasized the company’s product safety policies, health exam, and training program in order to rule out the possibility that other factors may influence perceived product quality. After reading the scenario, participants responded to a series of measures.

Perceived social responsibility was measured by participants’ agreement with three statements (1 = “Strongly Disagree”, 7 = “Strongly Agree”): “Subway is a socially responsible company,” “Subway is concerned to improve the well-being of society,” and “Subway follows high ethical standards” (α =0.91) (Wagner et al., 2009). Product evaluation was measured by three items (1 = “very poor quality,” “very poor taste,” “not at all delicious,” and 7 = “very good quality,” “very good taste,” “very delicious”; α =0.97) (Elder & Krishna, 2010). Purchase intention was measured by three items (1 = “unlikely,” “improbable,” “definitely not,” and 7 = “likely,” “probable,” “definitely”; α =0.94). Identification was measured using the same scale as in the pretest (α=0.95).

Study 2

The purpose of Study 2 was threefold. First, we sought to replicate the results from Study 1 by testing H2-H4. Second, in order to enhance generalizability, Study 2 used a different context. Namely, we examined a non-food context and a purchase in which the purchaser is not the consumer of the product. Third, we examined a different stigmatized population.

62 undergraduate students from a Canadian university (53% female) participated in the experiment which used the same design as in Study 1. Participants were first asked to imagine they are in a purchase situation to choose a model train as a birthday gift for their five-year-old nephew. They then read a scenario about a popular model train and the hiring practice behind the product. The scenarios used Study 1 as a template. Ex-convicts were chosen as the stigmatized population. After reading the scenario, participants responded to a series of measures. Product evaluation was measured by five items (1 = “bad” / 7 = “good”, 1 = “negative” / 7 = “positive”, 1 = “undesirable” / 7 = “desirable”, 1 = “unfavorable” / 7 = “favorable”, 1 = “dislike” / 7 = “like”; α = .97; Argo et al., 2006). Purchase intention used the same three-item scale in Study 1 (α =0.96).

Study 3

The purpose of Study 3 was to test H5 and H6. 195 undergraduate students (53.7% female) took part in a 2 (Producer Type: Stigmatized vs. Non-Stigmatized) X 2 (Degree of Physical Contact: High vs. Low) between-subjects experiment. The degree of physical contact between products and consumers was manipulated by using different product categories (i.e., cookies in high physical contact condition; clocks in low physical contact condition).

Four scenarios were created, using Study 1 as the template. Homeless people were chosen again as the stigmatized population. A description of job responsibility is added to the scenarios in order to hold the physical contact between producers and products at a constant level. Argo et al. (2006) disgust scale was adopted to measure disgust: “disgusted”, “revolted”, “unclean”, and “gross” coded 1 (not at all) to 7 (very) (α =0.93). Since people’s negative reactions to stigmatized populations also include ambivalence, dislike, fear, and anger (Jemmott et al., 1992), we adopted Argo et al. (2006) other negative emotions index with one added item: “frustrated”, “bad”, “annoyed”, “angry”, “mad”, and “fear” also coded 1 (not at all) to 7 (very) (α =0.93). The degree of physical contact between producers and products was measured by a 7-point scale anchored at 1 (low) and 7 (high). All other dependent measures followed those in Study 2 (product evaluation α =0.92, purchase intention α =0.90).

Results

Study 1 Results

Independent sample t-tests were conducted to examine the effect of producer type on perceived social responsibility, product evaluation, and purchase intention. Confirming H1, results reveal that participants rated the Subway restaurant that hires homeless people as more socially responsible than the restaurant that hires through an employment agency (MSTIGMATIZED = 5.84, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 4.78; t(51)=3.26, p<0.01). However, hiring homeless people lead to significantly lower product evaluation (MSTIGMATIZED = 4.19, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 4.91; t(46)=-2.34, p<0.05) and lower purchase intention (MSTIGMATIZED=3.38, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 4.73; t(51) =-2.76, p<0.01) than hiring through an employment agency. Thus, H2 and H3 were also supported.

We then conducted a mediation analysis using Model 4 of the PROCESS SPSS macro (Hayes, 2013). The regression model predicted purchase intention with producer type (0 = Stigmatized, 1 = NonStigmatized) as the independent variable and product evaluation as the mediator. Results based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples indicated that the indirect effect of producer type on purchase intention was significantly mediated by product evaluation (β = -.73, SE = .29; 95% CI = -1.34 – -.16). The direct effect of producer type on purchase intention was not significant (p>0.15). Taken together, the finding supports full mediation. Thus, H4 was supported.

Finally, an independent sample t-test showed that hiring homeless people did not lead to a stronger identification with the restaurant than hiring through an agency (MSTIGMATIZED = 4.05, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 4.02; t(51) < 1). Further analyses showed that age and gender neither predicted nor interacted with the independent variables to predict the dependent variables across all studies.

Study 2 Results

Two independent sample t-tests were conducted to examine the effect of producer type on product evaluation and purchase intention. The results supported H2 and H3. Product evaluations (MSTIGMATIZED = 2.97, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 4.90; t(60) = 10.81, p<0.001) and purchase intentions (MSTIGMATIZED = 2.11, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 4.80; t(60) = 13.55, p <0.001) were much lower when ex-convicts (versus non-stigmatized populations) are hired to produce the products. To test H4, we conducted a mediation analysis using Model 4 of the PROCESS SPSS macro (Hayes, 2013). The regression model predicted purchase intention with producer type (1 = Stigmatized, 0 = Non- Stigmatized) as the independent variable and product evaluation as the mediator. Results based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples indicated that the indirect effect of producer type on purchase intention was significantly mediated by product evaluation (β =0.59, SE = .31; 95% CI = .01 – 1.22). The direct effect of producer type on purchase intention was significant (p < .001). Taken together, the finding supports partial mediation.

Study 3 Results

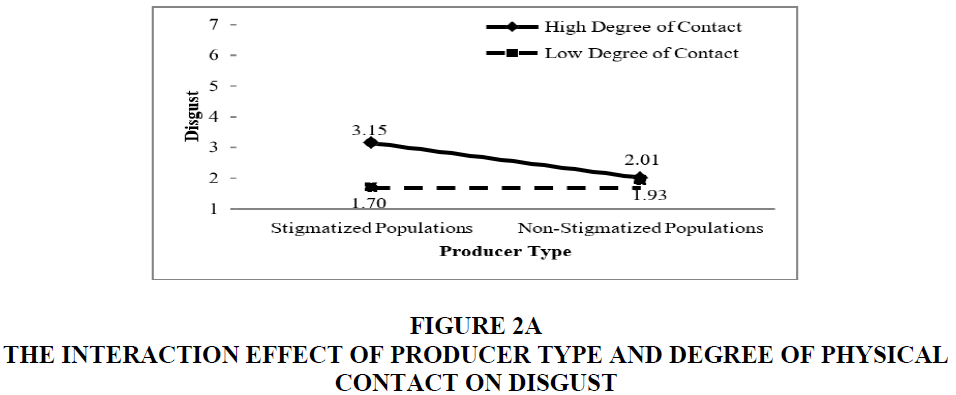

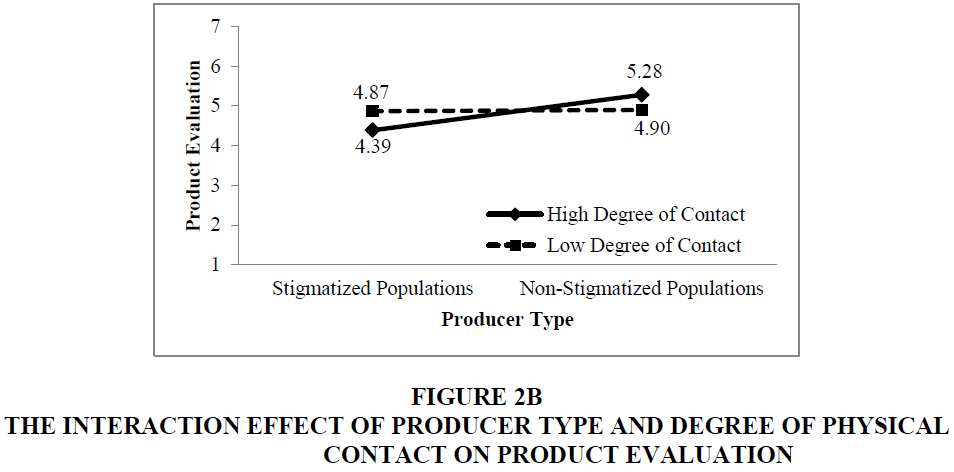

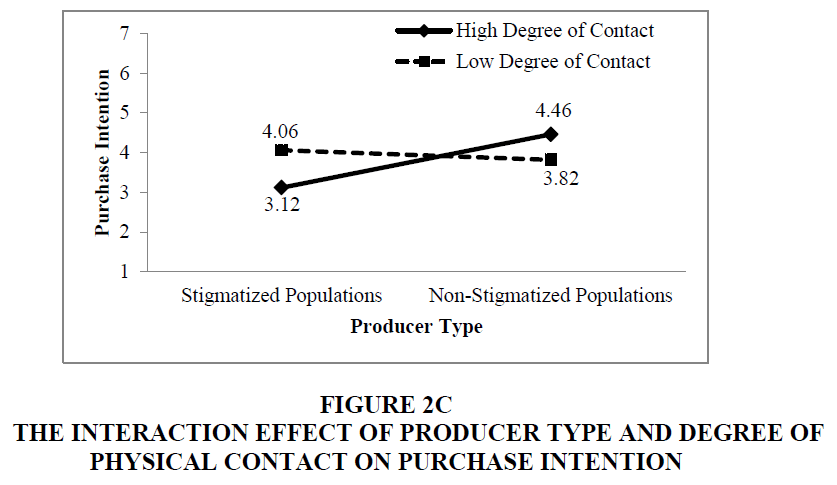

A confound check was first conducted to rule out the possibility that the level of physical contact between producers and products may affect the outcome measure. The results of independent sample t-test showed that participants perceived the newly hired producers have the same level of physical contact with cookies and clocks during the production process (MCOOKIE = 5.02, MCLOCK = 4.98, t < 1, p >0.80). Three two-way ANOVA tests were then conducted to examine H5 and H6, with producer type and degree of physical contact as the independent variables, and disgust, product evaluation, and purchase intention as the dependent variable in each two-way ANOVA test Figure 2A, 2B and 2C.

Figure 2B The Interaction Effect of Producer Type and Degree of Physical Contact on Product Evaluation

Figure 2C The Interaction Effect of Producer Type and Degree of Physical Contact on Purchase Intention

The results revealed that producer type and degree of physical contact together had significant interaction effect on disgust (F(1, 191) = 23.93, p <0.001), product evaluation (F(1, 191)= 10.64, p <0.001), and purchase intention (F(1, 191) = 21.53, p <0.001). Further analyses on simple main effect revealed that when participants had low degree of physical contact with the products (i.e., clocks), producer type had no significant impact on disgust (MSTIGMATIZED = 1.70, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 1.93), product evaluation (MSTIGMATIZED = 4.87, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 4.90), and purchase intention (MSTIGMATIZED = 4.06, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 3.82) (all ps >0.1). However, when participants had high degree of physical contact with the products (i.e., cookies), products produced by stigmatized populations lead to stronger feelings of disgust (MSTIGMATIZED=3.15, MNONSTIGMATIZED=2.01, F(1, 191) = 33.36, p<0.001), lower product evaluations (MSTIGMATIZED=4.39, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 5.28, F(1, 191)=22.63, p<0.001), and lower purchase intentions (MSTIGMATIZED = 3.12, MNONSTIGMATIZED = 4.46, F(1, 191)=30.71, p<0.001). Thus, hypotheses 5 and 6 were supported.

The serial multiple mediator model (Model 6 of the PROCESS SPSS macro) (Hayes, 2013) was used to test the mediation in H6. In the condition of high degree of physical contact, producer type (0 = Non-Stigmatized, 1 = Stigmatized) was modeled as affecting purchase intention through three indirect pathways and one direct pathway. Results based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples are summarized in Table 1. The indirect effect of producer type on purchase intention through disgust was insignificant (β = -0.16, SE =0.16; 95% CI = -0.49 –0.15). The indirect effect of producer type on purchase intention through product evaluation was significant (β=-0.12, SE =0.09; 95% CI = -0.38 – -0.001). The indirect effect of producer type on purchase intention through disgust and product evaluation sequentially, with disgust affecting product evaluation, was also significant (β = -0.21, SE = .09; 95% CI = -0.43 – -0.08). Finally, the direct effect of producer type on purchase intention was significant (β = -0.85, SE =0.27; 95% CI = -1.39 – -0.32). Taken together, the mediation in H6 was supported.

| Table 1 Regression Coefficients, Standard Errors, and Model Summary | |||||||||

| Disgust | Product Evaluation | Purchase Intention | |||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p |

| Producer Type | 1.14 | .23 | <.001 | -.33 | .20 | .101 | -.85 | .27 | <.005 |

| Disgust | ---- | ---- | ---- | -.49 | .08 | <.001 | -.14 | .13 | .277 |

| Product Evaluation | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | .37 | .14 | <.010 |

| Constant | 2.01 | .16 | <.001 | 6.26 | .21 | <.001 | 2.78 | .89 | <.005 |

| R2 = .21 | R2 = .39 | R2 = .34 | |||||||

| F(1, 95) = 25.64, p < .001 | F(2, 94) = 29.86, p < .001 | F(3, 93) = 16.15, p < .001 | |||||||

Finally, two-way ANOVA was conducted to test the interaction effect of producer type and degree of physical contact on other negative emotions. The results indicated that other negative emotions (i.e., frustrated, bad, annoyed, angry, mad, and fear) did not mediate the process (all ps >0.1).

Discussion

The results of the Study 1 and Study 2 demonstrate that consumers view a company that hires stigmatized populations as more socially responsible than a company that hires non- stigmatized populations. Notably, past research demonstrates a number of positive outcomes associated with developing positive CSR reputations such as higher purchase intentions (Ellen, 2006). However, the current research finds that consumers believe that the products produced by stigmatized populations have lower quality and tend to avoid purchasing the products. Study 2 replicated the findings in Study 1 in a non-food context, and a scenario in which the purchaser is not the consumer of the product. Moreover, Study 2 increases the generalizability of the results by using a different stigmatized population. Study 3 complements the first two studies by identifying the feeling of disgust as a key mediator and degree of physical contact between consumer and product as a moderator (H5 & H6). It shows that a high degree of physical contact between consumers and products is a premise to induce the backfire effect, and this process is mediated by consumers’ feelings of disgust. When the degree of physical contact is low, hiring stigmatized populations or not has no impact on consumers.

Theoretical Contributions

In exploring consumer responses to this CSR practice, this research makes a number of contributions. First, it offers an extension to previous research that seeks to understand the attitude- behavior gap in CSR research (e.g., Govind et al., 2019; Shaw et al., 2016). Although consumers typically view CSR positively and expect companies to be good corporate citizens, their product preferences are not always driven by CSR performance. The current research contributes to the literature by examining the underlying process by which positive perceptions of CSR activities can lead to inconsistent consumer actions. Even though hiring stigmatized populations is an act of social goodwill that is unrelated to a company’s core business, consumers believe it negatively affects product quality by inducing feelings of disgust. When consumers need to make a trade-off between ethical attributes and other valued attributes, they are unwilling to sacrifice taste or quality in their purchases in order to support the stigmatized populations. The examination of this inconsistency helps understand why some studies reported neutral or even negative relationships between CSR and profitability (Peloza & Papania, 2008). Broadly, this research responds to the call of Peloza & Shang (2011) for a better understanding of various CSR activities because not all CSR activities are viewed equally positive or positive at all by stakeholders.

Second, this research contributes to the research on the law of contagion by exploring the role of a new form of contagion, producer contagion. Previous marketing research on contagion focuses on consumer contagion (Argo et al., 2006, 2008; White et al., 2016), product contagion (Lin & Shih, 2016; Mishra, 2009; Morales & Fitzsimons, 2007), and celebrity contagion (Newman et al., 2011) but the opportunity for the producer to create contagion remains unexplored in the marketing literature. Furthermore, this research shows that visualization is not necessary to induce contagion effects (i.e., participants did not actually see the production process) and that negative producer contagion effects still exist when consumers are not the users of the products.

Finally, our research contributes to the research on discrimination of stigmatized populations in the workplace. Previous research shows that hiring managers are not willing to hire stigmatized populations for customer-facing positions (Bell et al., 2011; Hoque et al., 2018; Timming et al., 2017) but the employment chance increases if they apply for non-customer facing positions (Timming et al., 2017). However, our findings suggest that consumers still respond negatively even though the stigmatized employees are playing non-customer-facing roles.

Managerial Implications

For managers, the research highlights an important business consideration. Our findings reveal the circumstances under which hiring stigmatized populations may backfire and hurt the company. First, not all product categories would suffer from the backfire effect. Consumers are not influenced by this hiring practice when they have a low degree of physical contact with products such as lamps or wall clocks. In this case, although it cannot encourage consumers to buy more from the company, hiring people with social stigma can help a company build a good CSR reputation and receive financial incentives. On the contrary, companies that produce high-contact products (e.g., keyboards and bakery) are not “immune” to the backfire effect. Managers should decide whether they should launch this CSR program or whether they want to release the information to the public.

Research Challenges and Consideration

Stigmatized populations are diverse and some groups are more stigmatized than others by society (Cuddy et al., 2008). For example, although homeless, poor, welfare recipients, and drug addicts are all highly marginalized outgroups; homeless people are rated even more stigmatic than the other three groups (Cuddy et al., 2008). The current research only examines two groups of stigmatized populations, ex-convicts and homeless people. Second, intrinsic and altruistic CSR motives generate positive consumer responses (Groza et al., 2011). The scenarios in this research imply that the motive of the company to hire stigmatized populations is other-oriented. This may lead to more positive responses. If we do not emphasize the other-oriented motive of the company, consumers may make self-benefit inferences because companies that hire stigmatized populations (especially ex-cons) can get financial benefits such as tax credits. As a result, these attributions may lead to more negative attitudes toward the company and purchase intentions (Groza et al., 2011). Next, we recruited participants in Canada. Research shows that people in low-power- distance countries such as Canada engage in more prosocial behaviors because they feel more responsible to help others (Winterich & Zhang, 2014). Therefore, this may weaken the backfire effect of hiring stigmatized populations. Finally, although our research shows when this hiring practice may backfire and hurt a company, we did not explore what marketers can do to minimize or even eliminate this backfire effect. In the section below, we give suggestions on how to respond to the above research challenges.

Conclusion

Although it has becoming increasingly common for companies to hire stigmatized populations, our research reveals that this socially responsible hiring practice is not only ineffective but can backfire and hurt the company. Across three studies, we find that hiring stigmatized populations does not bring desired consume responses beyond a good CSR reputation. Our results demonstrate that consumers tend to avoid the products produced by stigmatized populations because the products induce consumers’ feelings of disgust, which negatively influence product evaluations and purchase intentions. This perception stems from the law of contagion – consumers believe that stigmatized populations can transfer their negative properties to the products during the production process and thus decrease the value of products although actual contamination does not occur. Moreover, consumers hold this perception not only when they purchase the products for themselves but also when they buy the products for other people. This phenomenon also has a boundary condition. Our research shows that this CSR practice backfires and leads to negative consumer responses when consumers have a high degree of physical contact with the products. When the degree of physical contact is low, hiring stigmatized populations or not has no impact on consumers.

Future research can explore the influence of various stigmatized populations such as veterans with PTSD or members of the LGBTQ community and consider the level of public stigma as a potential moderator. Second, future research can explore the role of positive producer contagion. For example, would the food prepared by a thin chef be viewed as healthier but less tasty than food prepared by an obese chef? Third, future research can examine the consumer response to a CSR activity that is the result of collaboration between a corporation and charitable organization whose focus is providing employment to stigmatized populations. For example, Service Source (Service Source, n.d.) is a US-based nonprofit that partners with government and commercial clients to provide meaningful employment for adults living with disabilities. The perceived motive and overall consumer response may in fact be altered when a corporation works directly with a charitable organization whose mission is to reduce stigma.

Finally, future research can find ways to overcome the backfire effect. Previous research demonstrates that explicit information such as stating that the quality of ethical products is as good as the quality of conventional products is effective in reducing the negative impact associated with ethical attributes (Luchs et al., 2010). Researchers can explore what statements can be used to reduce the negative impact associated with hiring stigmatized populations. Since disgust is a key mediator in negative producer contagion, the key of eliminating the backfire effect is reducing consumers’ feelings of disgust.

Color theory proposes that colors have symbolic value and cultural meanings because individuals repeatedly learn associations between colors and particular experiences and/or concepts (Elliot et al., 2007). These learned associations influence cognition and behavior (Elliot et al., 2007). White color is associated with both physical purity and moral purity (Sherman & Clore, 2009). Researchers may examine whether the usage of white color in advertising can overcome the negative effect and encourage purchases.

Moreover, previous research suggests that increasing people’s feelings of sympathy and understanding can successfully induce more positive responses toward stigmatized populations (Sikorski et al., 2015; Weiner, 1980). Although some companies have already tried to induce such feelings, the effectiveness of this practice is relatively unknown. For example, Starbucks (Starbucks Coffee, n.d.) and Airbnb (Airbnb, n.d.) not only provide job opportunities to the stigmatized populations but also try to change public stigma through marketing communications. They let the stigmatized employees tell their stories and post the videos on YouTube to let others better understand these groups.

Appendix 1: Study 1 Scenarios

East Side Continues to Develop

As the downtown east side continues to be “revitalized”, a major restaurant chain today opens its doors in a new location directly across from the new Woodward’s building on East Hastings.

Subway’s latest location is a sign of both economic recovery in the province, and particular economic recovery and investment into the downtown East Side. “This location is more than a typical new opening for us,” says Subway’s Regional Manager Mark Woods. “This store represents an investment in our communities perhaps more than any other store in the country. We are proud to be a part of the economic development of this community, and plan for a very successful partnership with our customers and the rest of the community.”

Mayor Gregor Roberson was on hand for the official ribbon cutting ceremony, and said the following: “It is wonderful to see this community developing in such a positive way. Subway has demonstrated its commitment to local communities across the country, and their investment is a sign of their confidence that our revitalization plan is working.”

Hiring Stigmatized Population

Manager Mark Woods stated that the biggest challenge in opening the restaurant was staffing. “The labour market is surprisingly tight in the downtown core,” he says. “That, and the fact that we wanted to showcase this location as a benchmark for our community involvement led us to our benchmark program to employ the homeless people from the area in our restaurant.”

“As far as I know it’s the first program of its kind,” explains UBC Sociology professor Debi Andrus. “Most companies shy away from employing homeless people, especially in such a public setting as a restaurant.”

But Mark Woods is committed. “We have confidence that we can help homeless people in this community find their way back. We also want to try our best to satisfy our customers. We strictly follow food safety policies. The people we’ve hired under this program have passed the health exam and have gained all sorts of skills in all parts of our business, from food preparation to cooking and handling to customer service. It’s a real win-win for everyone.”

Hiring Through an Employment Agency

Manager Mark Woods stated that the biggest challenge in opening the restaurant was staffing. “The labour market is surprisingly tight in the downtown core,” he says. “For the first time ever we’ve had to turn to an employment agency to help us find people to work in our new location. We worked with two companies to help find the people we need to staff the location across all shifts.”

“As far as I know it’s the first time a company like Subway has used an external agency for staffing purposes,” explains UBC Sociology professor Debi Andrus.

“Most companies try to stay away from this route because it tends to be much more expensive than hiring people directly through the restaurant location.”

But Mark Woods is committed. “We have confidence that the investment we make in this program will help us find employees that will remain with us for a long time. That lowers our long-term costs because we save on rehiring and retraining people each year. We also want to try our best to satisfy our customers. We strictly follow food safety policies. The people we’ve hired under this program have passed the health exam and have gained all sorts of skills in all parts of our business, from food preparation to cooking and handling to customer service. It’s a real win-win for everyone.”

References

- Aarikka-Stenroos, L., & Jaakkola, E., (2012). Value co-creation in knowledge intensive business services: A dyadic perspective on the joint problem-solving process. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(1), 15-26.

- Albrecht, K. (2016). Understanding the Effects of the Presence of Others in the Service Environment – A Literature Review. Journal of Business Market Management, 9(1), 541-563.

- Al-Eisawi, D.D. (2013). Modelling service excellence: the case of the UK banking sector. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University.

- Badgett, M., Moyce, M.S., & Kleinberger, H. (2007). Turning shoppers into advocates. IBM Institute for Business Value.

- Barsky, J., & Nash, L. (2002). Evoking emotion: Affective keys to hotel loyalty. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 43, 39.

- Berry, L.L., & Carbone, L.P. (2007). Build loyalty through experience management, Quality Progress, 40(9), 26-32.

- Berry, L.L., Carbone, L.P., & Haeckel, S.H. (2002). Managing the total customer experience. MIT Sloan Management Review, 43(3), 85-89.

- Berry, L.L., Wall, E.A., & Carbone, L.P. (2006). Service clues and customer assessment of the service experience: lessons from marketing. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(2), 43-57.

- Bigley, G.A., & Pearce, J.L. (1998). Straining for shared meaning in organizational science: Problems of trust and distrust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 405-421.

- Bitner, M.J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. The Journal of Marketing, 57-71.

- BOOMS, B.H., & BITNER, M.J. (1981). Marketing strategies and organization structures for service firms. In: Donnelly, J.H., George, W.R. (Eds.), Marketing of Services. American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL, 47-51.

- BOVE, L.L., PERVAN, S.J., BEATTY, S.E., & SHIU, E. (2008). Service worker role in encouraging customer organizational citizenship behaviours. Journal of Business Research, 62, 698-705.

- BRAKUS, J.J., SCHMITT, B.H., & ZARANTONELLO, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 52-68.

- BROCATO, E.D., VOORHEES, C.M., & BAKER, J. (2012). Understanding the Influence of Cues from Other Customers in the Service Experience: A Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Retailing, 88(3), 384-398.

- CARBONE, L.P., & HAECKEL, S.H. (1994). Engineering customer experience. Marketing Management, 3, 8-19.

- CARU, A., & COVA, B. (2007). Consuming experience. Oxon: Routledge

- CHATTOPADHYAY, A., & LABORIE, J.L. (2005). Managing Brand Experience: the Market Contact Audit, Journal of Advertising Research, 45(1), 9-16.

- Constantinides, E., Lorenzo-Romero, C., & Gómez, M.A. (2010). Effects of web experience on consumer choice: A multicultural approach. Internet Research, 20(2), 188-209.

- CRONIN, J.J. (2003). Looking back to see forward in services marketing: some ideas to consider, Managing Service Quality, 13(5), 332-7.

- DOBNI, B. (2002). A model for implementing service excellence in the financial services industry. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 7, 42-53.

- DUBROVSKI, D. (2001). The role of customer satisfaction in achieving business excellence, Total Quality Management, 12(7-8), 920-925.

- EDVARDSSON, B., & ENQUIST, B. (2011). The service excellence and innovation model: Lessons from IKEA and other service frontiers. Management and Business Excellence, 22(5), 535-551.

- ENNEW, C., & SEKHON H. (2007). Measuring Trust in Financial Services: The Trust Index, Consumer Policy Review, 17(2), 62-68.

- ESBJERG, L., JENSEN, B.B., BECH-LARSEN, T., DUTRA DE BARCELLOS, M., BOZTUG, Y., & GRUNERT, K.G. (2012). An integrative conceptual framework for analyzing customer satisfaction with shopping trip experiences in grocery retailing, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19(4), 445-456.

- FERNANDES, T., & NEVES, S. (2014). The role of servicescape as a driver of customer value in experience-centric service organizations: the Dragon Football Stadium case. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 22(6), 548-560.

- GARBARINO, E., & JOHNSON, M.S. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships, Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70-87.

- GARG, R., RAHMAN, Z., & QURESHI, M.N. (2014). Measuring customer experience in banks: scale development and validation, Journal of Modelling in Management, 9(1), 87-117.

- Gentile, C., Spiller, N., & Noci, G. (2007). How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European Management Journal, 25(5), 395-410.

- GILMORE, J., & PINE, B. (2002). Differentiating hospitality operations via experiences: why selling services is not enough. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 43(3), 87-96.

- Goi, M.T., & Kalidas, V. (2015). Effect of Servicescape on Emotion, Mood, and Experience among HEI students. World Review of Business Research, 6(1), 81-91.

- GOUNARIS, S. (2005). Measuring service quality in b2b services: an evaluation of the SERVQUAL scales vis-à-vis the INDSERV scale. Journal of Services Marketing, 19(6), 421-435.

- GRACE, D., & O'CASS, A. (2004). Examining service experiences and post-consumption evaluations. Journal of Services Marketing, 18(6), 450-461.

- GREENWOOD, M., & BUREN, H. (2010). Trust and stakeholder theory: Trustworthiness in the organization-stakeholder relationship, Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 425- 438.

- GREWAL, D., LEVY, M., & KUMAR, V. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 1-14.

- GRÖNROOS, C. (2008). Service logic revisited: who creates value? And who co-creates? European Business Review, 20(4), 298-314.

- GROTH, M. (2005). Customers as good soldiers: Examining citizenship behaviours in internet service deliveries. Journal of Management, 31, 7-27.

- GROVE, S.J., & FISK, P.R. (1997). The Impact of Other Customers on Service Experiences: A Critical Incident Examination of Getting Along. Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 63-85.

- HARRIS, L.C., & EZEH, C. (2008). Servicescape and loyalty intentions: an empirical investigation. European Journal of Marketing, 42(3-4), 390-422.

- HARRIS, R., ELLIOTT, D., & BARON, S. (2011). A Theatrical Perspective on Service Performance Evaluation: The Customer-Critic Approach, Journal of Marketing Management, 27(5-6), 477-502.

- Hill, A.V., Collier, D.A., Froehle, C.M., Goodale, J.C., Metters, R.D., & Verma, R. (2002). Research opportunities in service process design. Journal of Operations Management, 20, 189‐202.

- HOLBROOK, M., & HIRSCHMAN, E. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 132-140.

- HOLBROOK, M. (2006). The Consumption Experience – Something New, Something Old, Something Borrowed, Something Sold: Part 1, Journal of Macromarketing, 26(2), 259-266.

- ISMAIL, A.R. (2010). Investigating British customers’ experience to maximise brand loyalty within context of tourism in Egypt: Netnography and structural modelling approach, Published Ph.D Thesis, Brunel University, London.

- ISMAIL, A.R., MELEWAR, T.C., LIM, L., & WOODSIDE, A. (2011). Customer Experiences with Brands: Literature Review and Research Directions. The Marketing Review, 11(3), 205-225.

- Johnston, R. (2004). Towards a Better Understanding of Service Excellence. Managing Service Quality, 14(2-3), 14.

- JOHNSTON, R. (2007). The Internal Barriers to Improving External Service, in: Ford, R.C. et al. (Eds.), Managing Magical Service, The Rosen College of Hospitality, Florida: USA, 179-188.

- KEAVENEY, S.M. (1995). Customer switching behaviour in service industries: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing, 59(2), 71-82.

- KHAN, H., & MATLAY, H. (2009). Implementing service excellence in higher education. Education and Training, 51(8-9), 769-780.

- KIM D. J., FERRIN D.L., & RAO, H.R. (2009). Trust and satisfaction, the two wheels for successful e-commerce transactions: a longitudinal exploration. Information System Research, 20(2), 237-257.

- KIM, S., KNUTSON, B., & BECK, J. (2011). Development and testing of the Consumer Experience Index (CEI), Managing Service Quality, 21(2), 112-132.

- KLAUS, P., & MAKLAN, S. (2012). EXQ: a multiple-scale for assessing service experience. Journal of Service Management, 23(1).

- KOTLER, P. (2005). The role played by the broadening of marketing movement in the history of marketing thought. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 24(1), 114-116.

- LATANE, B. (1981). The Psychology of Social Impact. American Psychologist, 36, 343-356.

- LEWIS, B.R., & GABRIELSEN, G.O.S. (1998). Intra-organizational aspects of service quality management: the employees’ perspective, The Service Industries Journal, 18(2), 64-89.

- LIN, H.F. (2011). An empirical investigation of mobile banking adoption: The effect of innovation attributes and knowledge-based trust. International Journal of Information Management, 31(3), 252-260.

- MAKLAN, S., & KLAUS, P. (2011). Customer experience: are we measuring the right things? International Journal of Marketing Research, 53(6), 771-792.

- MAYER, R.C., DAVIS, J.H., & SCHOORMAN, F.D. (1995a). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy. Management Review, 20(3), 709-734.

- MEYER, C., & SCHWAGER A. (2007). Understanding Customer Experience. Harvard Business Review, 85(2), 117-26.

- MORGAN, R., & HUNT, S. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing, Journal of Marketing, 58, 20-38.

- PALMER, A., 2010. Customer experience management: a critical review of an emerging idea. Journal of Services Marketing. 24 (3), 196– 208.

- PAREIGIS, J., ECHEVERRI, P. and EDVARDSSON, B., 2012. Exploring internal mechanisms forming customer servicescape experiences. Journal of Service Management, 23, 677– 695.

- Patrício, L., Fisk, R.P. and Cunha, J., 2008. Designing multi‐interface service experiences: the service experience blueprint. Journal of Service Research, 10, 318‐34.

- PINE, B.J and GILMORE J.H., 1998. Welcome to the Experience Economy, Harvard Business Review, 76 (4), 97-105.

- Pine, B.J., & Gilmore, J.H. (2003). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76.

- PONSIGNON, F., PHILIPP, K., & MAULL, R.S. (2015). Experience Co-Creation in Financial Services: An Empirical Exploration. Journal of Service Management, 26(2), 295-320.

- Roth, A.V., & Menor, L.J. (2003). Insights into service operations management: a research agenda. Production and Operations Management, 12, 145‐64.

- RUNDLE-THIELE, S., & MACKAY, M., 2001. Assessing the performance of brand loyalty measures. Journal of Services Marketing, 15(7), 529-546.

- SANDSTROM, S., EDVARDSSON, B., KRISTENSSON, P., & MAGNUSSON, P. (2008). Value in Use through Service Experience. Managing Service Quality, 18(2), 112-126.

- SCHMITT, B.H. (1999). Experiential Marketing. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data, New York.

- SCHMITT, B.H. (2003). Customer experience management. A revolutionary approach to connecting with your customers. New Jersey, John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- SHAW, C., & IVENS, J. (2002). Building Great Customer Experiences, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

- Shaw, C., & Ivens, J. (2005). Building great customer experiences. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

- SINGH, J., & SIRDESHMUKH, D. (2000). Agency and trust mechanisms in consumer satisfaction and loyalty judgments. Journal of Academy Marketing Science. 28(1), 150-167.

- SIRDESHMUKH, D., SINGH, J., & SABOL, B. (2002). Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. Journal of Marketing, 66, 15-37.

- SIVARAJAH, R. (2014). The Impact of Consumer Experience on Brand Loyalty: The Mediating Role of Brand Attitude, International Journal of Management and Social Sciences Research, 3(1), 73-79.

- SMITH, S., & WHEELER, J. (2002). Managing the customer experience: Turning customers into advocates, Prentice Hall, London.

- STUART, I., & TAX, S. (2004). Toward an integrative approach to designing service experiences, Lessons learned from the theatre. Journal of Operations Management, 22, 609-627.

- SUH, B., & HAN, I. (2003). Effect of trust on customer acceptance of internet banking. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 1(3), 247-263.

- Teixeira, J., Patrício, L., Nunes, N.J., Nóbrega, L., Fisk, R.P., & Constantine, L. (2012). Customer experience modelling: from customer experience to service design. Journal of Service Management, 23(3), 362-376.

- Turnois, L. (2004). Creating customer value: bridging theory and practice. Journal of Marketing Management. 14(2), 12‐23.

- VARGO, S.L., & LUSCH, R.F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. The Journal of Marketing, 68, 1-17.

- VERHOEF, P., LEMON, K., PARASURAMAN, A., ROGGEVEEN, A., SCHLESINGER, L., & TSIROS, M. (2009). Customer Experience: Determinants, Dynamics and Management Strategies. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 31-41.

- WALTER, U., EDVARDSSON, B., & OSTROM, A. (2010). Drivers of customers’ service experiences: a study in the restaurant industry. Managing Service Quality, 20(30), 236-258.

- WINER, R.S. (2001). A framework for customer relationship management. California Management Review, 43, 89-105.

- XIE, C., BAGOZZI, R.P., & TROYE, S.V. (2008). Trying to prosume: Toward a theory of consumers as co-creators of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36, 109-122.

- YAVAS, U., KARATEPE, O.M., AVCI, T., & TEKINKUS, M. (2003). Antecedents and outcomes of service recovery performance: An empirical study of frontline employees in Turkish banks. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 21(5), 255-265.

- YI, Y., & GONG, T. (2008). If employees “go the extra mile”, do customers reciprocate with similar behaviour? Psychology and Marketing, 25, 961-986.

- YI, Y., NATARAAJAN, R., & GONG, T. (2011). Customer participation and citizenship behavioural influences on employee performance, satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intention. Journal of Business Research, 64, 87-95.