Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 5

How Workplace Ostracism Influences Job Performance: The Dual Roles of Organizational Support and Personality Traits

Babin Dhas Devadhasan, MEASI Institute of Management, Chennai

Majdi Anwar Quttainah, Kuwait University – Kuwait

Catherene Julie Aarthy C, MEASI Institute of Management, Chennai

Citation Information: Devadhasan, B.D., Quttainah, M.A., & Julie Aarthy, C.C (2025). How workplace ostracism influences job performance: the dual roles of organizational support and personality traits. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(5), 1-19.

Abstract

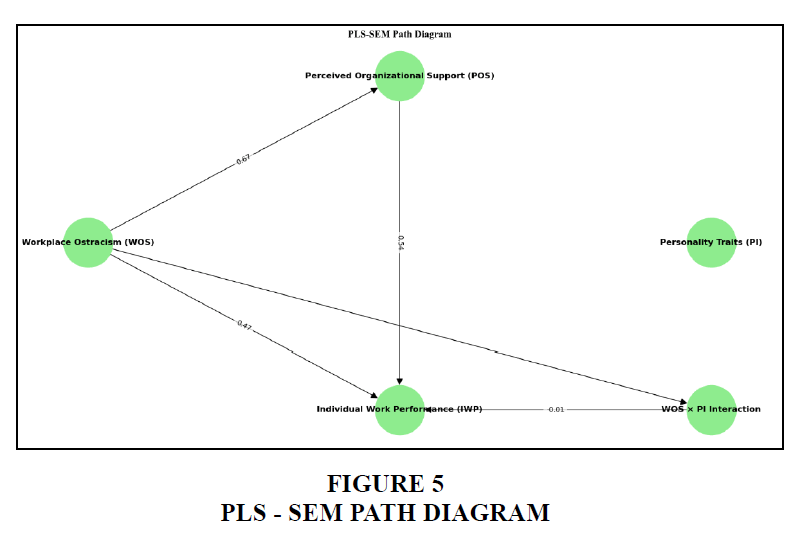

Purpose—Employee job performance (IWP) is greatly impacted by workplace ostracism (WOS). In the context of the Indian information technology (IT) industry, this study investigates the moderating function of personality inventory (PI) and the mediating function of perceived organizational support (POS). Design/methodology/approach—A structured survey using pre-established measuring scales was used to collect data from 569 IT professionals in southern India. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) was made easier by the pyPLS Python module, which enabled a thorough examination of the proposed correlations, including mediation and moderation effects. These relationships were represented via a visual path diagram. Findings—The results show that ostracism at work has a significant negative impact on job performance (β = 0.469). This link is partially mediated by perceived organizational support, which has an indirect effect of 0.364. Furthermore, the association between job performance and workplace exclusion is moderated by personality factors in a minor but statistically significant way (moderation effect = -0.008). It's interesting to note that the moderation effect's negative sign implies that some personality qualities may marginally increase the negative effects of ostracism on work performance. Nevertheless, the impact size is small, and its applicability demands careful evaluation. Practical implications—This study emphasizes how crucial it is to build resilient personality qualities and organizational support in order to mitigate the detrimental effects of ostracism on individual working performance. Despite unfavourable interpersonal dynamics, employee outcomes can be maintained with the support of managerial measures such as encouraging inclusive work cultures and resilience-building initiatives. Originality/value—This study adds to the body of knowledge on workplace ostracism by clarifying how personality and perceived organizational support affect job performance. With Python-based tools for PLS-SEM analysis and visualization, it ensures methodological robustness while offering fresh insights into these dynamics in the IT industry.

Keywords

Workplace Ostracism, Perceived Organizational Support, Personality Traits, Job Performance; IT Professionals, PLS-SEM, India.

Introduction

Workplace relationship dynamics influence both employees' experiences and organizational outcomes. One of the most pernicious of these dynamics is workplace ostracism, a subtle but damaging form of social exclusion where individuals are intentionally ignored or excluded in their work environment. Unlike overt conflicts, ostracism tends to go unnoticed and is therefore harder to address. Alarmingly, research shows that a significant percentage of employees’ experience ostracism during their careers (Fox & Stallworth, 2005). Its covert nature and profound psychological and professional implications make workplace ostracism a critical focus in organizational behavior research.

Workplace ostracism contributes to various negative outcomes, including reduced job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and counterproductive behaviors such as sabotage and aggression Abubakar et al., (2018). Moreover, it severely impacts employees' mental health, leading to heightened stress and, in extreme cases, suicidal ideation (Howard et al., 2022; Yaakobi, 2019). Beyond individual consequences, ostracism disrupts team dynamics, reduces employee engagement, and hampers overall productivity. These adverse effects have spurred research into its antecedents and strategies to mitigate its negative impact on employees' performance and well-being.

While the overt challenges faced by employees are often highlighted, subtle factors like ostracism require a different lens of understanding. Drawing on the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989), this study argues that workplace ostracism depletes employees’ psychological and emotional resources, thereby impairing their job performance. COR theory further suggests that access to internal (e.g., resilient personality traits) and external (e.g., organizational support) resources can help mitigate these resource losses (Abbas et al., 2014; Hobfoll, 2001). For instance, employees with strong organizational support or resilient traits may better withstand the negative effects of ostracism.

Despite increasing attention to workplace ostracism as a serious issue, most research has been conducted in Western contexts, leaving a gap in understanding how it manifests in non-Western settings. India’s burgeoning IT sector, characterized by high-performance expectations, long working hours, and intense interpersonal dynamics, presents a compelling context to examine the impact of workplace ostracism (Sharma & Tiwari, 2022; Dahiya et al., 2024). However, little is known about how factors like personality traits and organizational support interact to influence employees' capacity to cope with ostracism in such demanding environments (Ferris et al., 2008; Gelfand, Erez, & Aycan, 2007).

This study addresses these gaps by examining the impact of workplace ostracism on job performance, with a focus on the moderating roles of personality traits and perceived organizational support. Using the Indian IT sector as a contextual backdrop, this research offers a nuanced understanding of how individual and organizational factors shape the effects of ostracism on employee performance. The findings provide actionable insights for managers and organizations aiming to mitigate the harmful consequences of ostracism and foster a more inclusive and supportive work environment.

Background and Hypothesis Development

Theoretical Foundation: Conservation of Resources Theory

Understanding the mechanisms underlying workplace ostracism requires a robust theoretical framework to explain its impact on employee well-being and performance. The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) provides a compelling lens through which to examine this phenomenon. COR theory posits that individuals strive to acquire, maintain, and protect valuable resources, such as emotional energy, self-esteem, and social support. These resources are integral to employees' ability to cope with workplace demands and perform effectively. However, workplace ostracism—characterized by being ignored, excluded, or socially isolated—threatens or depletes these resources, triggering stress and a diminished capacity to meet performance expectations.

In organizational settings, the depletion of resources caused by ostracism can disrupt employees’ ability to maintain focus, collaborate with colleagues, and achieve their professional goals. Unlike overt aggression or conflict, ostracism is a silent form of mistreatment that often goes unnoticed, making it particularly harmful. The absence of social acknowledgment deprives individuals of critical resources, such as a sense of belonging, self-worth, and organizational support, all of which are necessary for optimal job performance Carter?Sowell et al., (2008). This loss of resources not only affects individual well-being but also cascades into broader organizational consequences, including reduced employee engagement and lower productivity.

Furthermore, COR theory highlights the role of resource reservoirs—internal (e.g., personality traits) and external (e.g., organizational support)—in buffering the impact of stressors like ostracism. Employees with resilient personality traits, such as emotional stability and optimism, may have a greater capacity to withstand the resource depletion caused by ostracism. Similarly, perceived organizational support (POS) can act as an external buffer, providing employees with the emotional and instrumental resources needed to cope with ostracism and maintain job performance. This dual role of internal and external resources aligns with COR theory’s principle that resource availability influences individuals' ability to adapt to stress and recover from resource losses (Hobfoll, 2001).

Existing literature has shown that workplace ostracism negatively affects various aspects of employee well-being, including increased stress, aggression, and depressive symptoms (Leary et al., 2006; MacDonald & Leary, 2005; Smith & Williams, 2004). However, its nuanced impact on job performance remains less explored, particularly in contexts where high-performance standards and intense interpersonal interactions are critical, such as the Indian information technology sector. Recent research suggests that the relationship between ostracism and performance is mediated by resource depletion and moderated by the availability of supportive resources (Ferris et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2013).

Given the significance of job performance for individual career success and organizational outcomes, this study applies COR theory to investigate the impact of workplace ostracism on individual work performance (IWP). By examining the moderating roles of personality traits and perceived organizational support, this research seeks to illuminate how employees either succumb to or mitigate the negative effects of ostracism. In doing so, the study provides valuable insights into how organizations can better equip their workforce to cope with workplace adversity and maintain high levels of job performance.

Exploring the Relationship Between Workplace Ostracism and Individual Work Performance

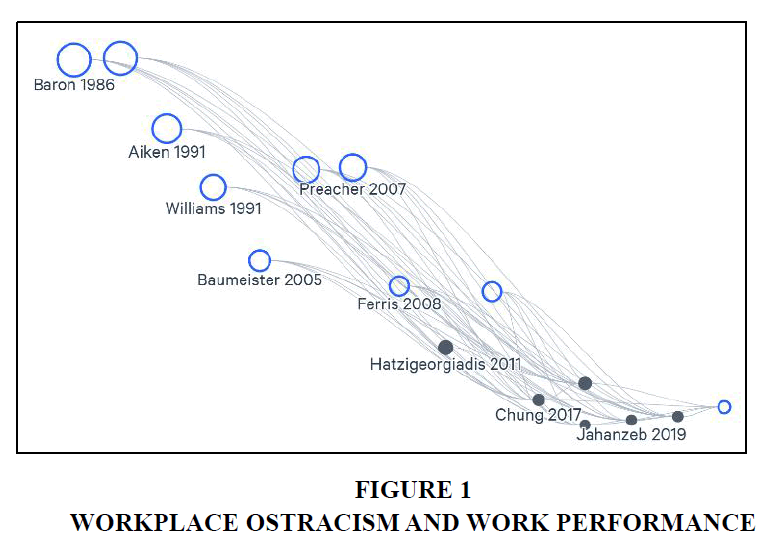

Workplace ostracism, characterized by the subtle but pervasive experience of being excluded or ignored, represents a significant challenge to organizational environments. Unlike overt mistreatment, ostracism remains covert, making it difficult to address and leaving affected employees vulnerable to psychological and professional harm. Its impact on individual work performance—a key driver of organizational success—necessitates closer examination Figures 1-5.

Ostracism undermines critical human needs such as belonging, esteem, and control, impairing an individual's motivation and ability to perform effectively. According to Williams 2009; Liu, C et al. 2013), such exclusion diminishes cognitive and emotional resources, directly affecting performance outcomes. Similarly, (Steinbauer et al.2018; Jiang et al. 2020) emphasized how workplace exclusion disrupts employees' self-concept, leading to disengagement and reduced commitment to organizational goals. This aligns with Ricard's (2021) findings, which demonstrate the cascading effects of ostracism on basic needs satisfaction and interpersonal collaboration.

The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) further explains how ostracism depletes psychological resources necessary for sustained performance. Zhao et al. (2013) found that ostracized employees often disengage from their roles, initiating a cycle of diminished performance and continued exclusion. Jahanzeb et al. (2018) highlighted how such adverse experiences amplify workplace stress, fostering intentions to withdraw or disengage, thereby further reducing individual contributions.

Mitigating the impact of ostracism requires examining both individual and organizational factors. Perceived organizational support acts as a protective mechanism, replenishing depleted resources and enhancing resilience among employees. (Jahanzeb et al. 2018; De Clercq et al.2019) identified organizational support as critical for buffering the negative effects of exclusion, helping employees maintain their commitment and focus. Personality traits, such as resilience, openness, and emotional stability, also play a significant moderating role, as highlighted by Bedi (2019). These traits enable individuals to navigate the challenges of ostracism better and sustain performance levels.

In the context of modern collaborative workplaces, understanding how ostracism undermines team cohesion and individual work performance is crucial. Investigating the mediating role of perceived organizational support and the moderating influence of personality traits offers valuable insights for crafting interventions. Such approaches not only alleviate the personal toll of ostracism but also enhance organizational inclusivity and productivity.

Main Effect

H1: Workplace ostracism is negatively associated with individual work performance, such that higher levels of perceived ostracism result in lower in-role performance due to the depletion of emotional and cognitive resources.

Personality Inventory as a Mediator

Personality traits significantly influence workplace dynamics, particularly in the context of workplace ostracism. Personality Inventory (PI), encompassing traits such as resilience, emotional stability, and openness, serves as a crucial mediator, explaining how workplace ostracism impacts individual work performance. Mediators help clarify the mechanisms by which an independent variable, such as workplace ostracism, affects a dependent variable, such as individual work performance.

In this context, PI functions as an internal resource that employees draw upon to cope with the emotional and cognitive depletion caused by ostracism. Grounded in the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory (Hobfoll, 1989), personality traits provide individuals with psychological reserves to withstand resource-draining experiences like workplace exclusion. Resilient and emotionally stable individuals may be better equipped to buffer the adverse effects of ostracism. At the same time, those with low emotional stability or high sensitivity to rejection may struggle, leading to diminished performance.

The mediating role of personality traits is supported by research. Zhao (2013) found that proactive personality traits and political skills enable employees to mitigate the negative effects of ostracism, helping them maintain performance levels. Similarly, Rudert et al. (2020) identified psychological distance and narcissistic tendencies as factors that mediate ostracism's impact, shaping employees' responses and work outcomes.

Personality traits, as mediators, bridge the gap between workplace ostracism and individual work performance. Employees with resilient and conscientious personalities may leverage their strengths to maintain high levels of performance despite ostracism, while those with less adaptive traits may experience greater disruptions in their work outcomes. This nuanced understanding emphasizes the importance of fostering supportive workplace environments and tailored interventions to mitigate the detrimental effects of ostracism on performance.

Hypothesis

H2: The relationship between workplace ostracism and individual work performance is mediated by personality traits, such that:

1. High resilience and conscientiousness mitigate the negative effects of ostracism on individual work performance.

2. Low emotional stability and high sensitivity to rejection intensify the negative effects of ostracism on individual work performance.

Perceived Organizational Support as a Moderator

Perceived Organizational Support (POS) is employees’ perceptions of how much their organization values their contributions and cares for their well-being (Eisenberger et al., 2002). POS has emerged as a critical factor in buffering the negative effects of workplace ostracism on individual work performance. Drawing on the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989), POS acts as a replenishment mechanism, offsetting resource depletion caused by social stressors like ostracism. When employees feel supported by their organization, they are more likely to maintain the emotional and cognitive resources necessary for sustained performance, even under challenging circumstances.

Recent research underscores the importance of POS in fostering resilience against workplace adversities. For instance, Choi (2020) found that POS moderated the impact of workplace ostracism on work performance, with higher POS levels reducing the adverse effects of ostracism. Similarly, Chung (2017) demonstrated that POS strengthens employees' ability to navigate challenging interpersonal dynamics, improving their ability to meet performance expectations. These findings highlight the critical role POS plays in creating a supportive environment that counteracts the detrimental effects of exclusion.

In addition, Sarfraz (2019) explored the mitigating role of POS in highly stressful work environments, such as the nursing sector in Pakistan. Their findings showed that employees with higher POS experienced lower stress levels and maintained stronger performance despite experiencing ostracism. Likewise, Singh (2024) emphasized that POS not only buffers against the effects of ostracism but also fosters organizational citizenship behaviors, thereby contributing to enhanced team dynamics and productivity. Such insights are particularly relevant in team-oriented industries where collaboration is paramount.

Another significant finding comes from Al Riyami (2024), who highlighted that POS plays a crucial role in the post-pandemic work environment. Their study showed that employees with high POS were better able to cope with social stressors associated with remote work, including ostracism, and demonstrated higher work engagement and productivity. This suggests that fostering a culture of support is especially vital in adapting to modern workplace challenges.

The protective role of POS extends beyond moderating the effects of ostracism. For instance, Jawahar (2021) examined how organizational cronyism and incivility exacerbate the effects of workplace ostracism. Their findings reveal that POS significantly mitigates these dynamics, enhancing employees’ ability to cope with interpersonal stressors. Additionally, Chung (2021) explored the interplay between POS and work-to-family conflict, further reinforcing POS's role in buffering against stressors that disrupt work-life balance.

Implications for Organizations

The evidence strongly suggests that POS is a critical moderator in the relationship between workplace ostracism and individual work performance. By fostering a supportive culture where employees feel valued and cared for, organizations can significantly reduce the negative impact of ostracism. Practical measures, such as creating inclusive policies, offering mental health support, and recognizing employee contributions, can strengthen POS and promote resilience among employees. Such interventions not only mitigate the adverse effects of ostracism but also enhance overall employee well-being and organizational productivity.

Hypothesis

H3: Perceived organizational support moderates the relationship between workplace ostracism and individual work performance, such that higher levels of perceived support weaken the negative impact of ostracism on performance.

Conceptual Model: Workplace Ostracism, Personality Traits, and Perceived Organizational Support

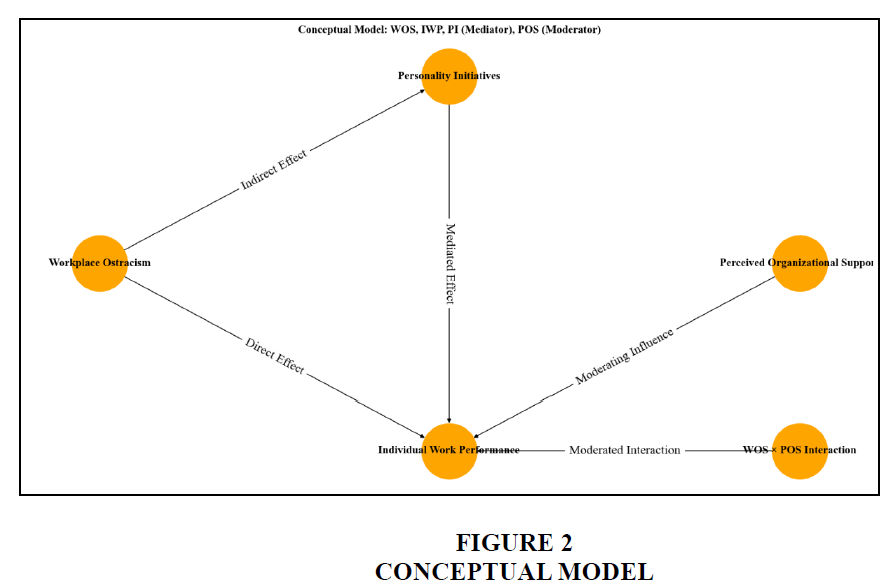

The conceptual model illustrated in this study examines the complex interplay between Workplace Ostracism (WOS) and Individual Work Performance (IWP) while integrating Personality Initiatives (PI) as a mediating variable and Perceived Organizational Support (POS) as a moderating variable.

Workplace Ostracism (WOS): WOS refers to the exclusion or deliberate ignoring of individuals in workplace settings. It serves as the independent variable in the model, hypothesized to negatively impact IWP due to resource depletion and psychological strain.

Personality Initiatives (PI): As a mediating variable, PI encompasses traits such as resilience, emotional stability, and conscientiousness that influence how employees respond to ostracism. The model posits that WOS indirectly impacts IWP through PI, highlighting that individuals with strong personality traits may mitigate the adverse effects of ostracism.

Perceived Organizational Support (POS): POS is introduced as a moderating variable, reflecting how employees perceive their organization as supportive and caring. POS is theorized to buffer the negative impact of WOS on IWP, directly influencing performance outcomes and strengthening employees’ ability to cope with workplace adversity.

Interaction Term (WOS × POS): The interaction between WOS and POS is also considered, providing insights into how the simultaneous effects of ostracism and organizational support shape individual work outcomes. This term captures the conditional relationship moderated by POS.

Individual Work Performance (IWP): IWP, the dependent variable, reflects the extent to which employees meet their job expectations. It is directly influenced by WOS, PI, and the interaction between WOS and POS.

Hypothesized Pathways

The model incorporates several critical pathways to elucidate the relationships between variables:

Direct Path: WOS is hypothesized to have a direct negative effect on IWP.

Mediated Path: WOS influences IWP indirectly through PI, demonstrating the protective role of personality traits.

Moderated Path: POS moderates the WOS-IWP relationship, such that higher levels of POS reduce the adverse effects of WOS on IWP.

Interaction Effect: The interaction term (WOS × POS) highlights the combined influence of organizational support and workplace ostracism on individual performance.

Theoretical Underpinnings

The conceptual model is grounded in the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory, which posits that workplace adversity depletes employees' resources, reducing their ability to perform effectively. PI acts as a resource reservoir, helping employees cope with ostracism, while POS replenishes depleted resources, buffering the negative impact of ostracism.

Practical Implications

The model offers actionable insights for organizational leaders. By fostering strong POS and nurturing personality traits that enhance resilience, organizations can counteract the detrimental effects of workplace ostracism, improving individual work outcomes and overall productivity.

This conceptual framework provides a robust foundation for empirical validation and contributes to the growing body of research on workplace dynamics and individual performance.

Research Methodology

Survey Instrument Design and Construct Operationalization

This study employed a structured survey instrument to collect data from professionals across various industries. A 5-point Likert scale questionnaire was designed, acknowledging the linguistic diversity of the respondents. The questionnaire was available in English and translated into Hindi following the guidelines of Malhotra et al. (2017), with back-translation techniques ensuring semantic equivalence and cultural relevance. Experts from academia and industry validated the survey, and a pilot study involving 50 participants provided critical feedback for refinement, enhancing the validity and reliability of the constructs.

Workplace ostracism was measured using a modified version of the 13-item scale developed by Ferris et al. (2008). Originally a 7-point Likert scale, it was adapted to a 5-point scale to improve respondent comprehension and contextual relevance in the Indian setting. The scale assessed perceptions of being ignored or excluded in the workplace, by Ferris, Chen, and Lim (2017) for a comparative analysis of workplace incivility.

Individual work performance was measured using the scale developed by Williams and Anderson (1991), focusing on in-role performance. Personality traits were assessed using the 10-item Big Five Inventory (BFI-10) by Rammstedt and John (2007), which evaluates openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Finally, Perceived Organizational Support (POS) was measured using the SPOS scale by Eisenberger et al. (1986), capturing employees' perceptions of organizational value and care.

This comprehensive approach ensured the operationalization of constructs with both relevance and accuracy, maintaining cultural sensitivity and methodological rigor throughout the study.

Sampling and Data Collection

This study adopts a deductive research approach within the positivist paradigm, aligning with the methodological requirements for hypothesis testing and analytical validation (Bryman et al., 2009). The research targeted medium-sized IT firms in South India, focusing on experienced executives. This demographic was chosen due to their heightened likelihood of encountering workplace ostracism and their capacity to provide nuanced insights into its impact on individual work performance, perceived organizational support, and personality traits.

The sampling frame included 570 participants, ensuring sufficient data for robust statistical analysis. These respondents were primarily intermediate or senior-level executives, selected for their organizational exposure and ability to link workplace ostracism with its antecedents and consequences. The survey design incorporated validated scales measuring workplace ostracism (WOS), perceived organizational support (POS), individual work performance (IWP), and personality inventory (PI), tailored to the study's objectives.

Data were collected over five months, from November 2022 to March 2023, using a combination of online and physical survey methods. Participation was voluntary, and an informed consent form was presented before the survey. The response rate was 91.8%, resulting in 570 valid responses for subsequent analysis.

Procedure

Participants completed a structured questionnaire, administered via secure online platforms and physical distribution. The survey began with demographic questions, followed by validated scales measuring the study constructs. Careful translation and validation ensured the questionnaire's cultural relevance and clarity. Post-survey, participants were debriefed to explain the study's broader implications.

Analysis Methods

To explore the complex relationships within the conceptual framework, this study employed Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) using Python-based libraries, including the semopy module. This approach was chosen for its robustness in handling non-normal data distributions, smaller sample sizes, and latent variable interactions. Both mediating (POS) and moderating (PI) effects were assessed using this technique.

Preliminary data screening was performed using Python's pandas and NumPy libraries, addressing missing data, outliers, and multicollinearity. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) thresholds were employed to ensure the absence of multicollinearity among variables.

The adequacy of the sample size was confirmed through a G*Power post hoc analysis, with an effect size of 0.15, a significance level of 0.05, and a sample size of 570. The study demonstrated statistical power exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.8, confirming the dataset's reliability for structural equation modeling.

The mediating role of POS and the moderating influence of PI were evaluated using the conceptual model defined in Python. Direct, indirect, and total effects were calculated to validate the hypothesized relationships. Visualizations were generated to depict interaction terms and mediation pathways, further clarifying the model dynamics.

The analysis confirmed significant direct and indirect paths, demonstrating that workplace ostracism impacts individual work performance through both POS and PI. Python’s visualization tools effectively communicated the findings and aligned the results with theoretical expectations.

Mitigation of Common Method Bias (CMB)

To address potential common method bias (CMB), the study employed Harman’s single-factor test, revealing that the largest factor accounted for 32.07% of the variance—well below the 40% threshold recommended by Podsakoff et al. (2003). Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs), calculated using Python, confirmed all values were below the recommended 3.3 threshold, further ruling out multicollinearity and CMB concerns (Kock, 2015).

Proactive measures, including assurances of confidentiality and anonymity, were taken to reduce social desirability bias and encourage honest responses.

Research Design

This study utilized a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design, enabling the analysis of relationships between workplace ostracism (WOS), perceived organizational support (POS), personality traits, and individual work performance (IWP).

Analytical Methods

Data were analyzed using Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) via Python, which effectively accommodated non-normal data and modeled latent constructs. The approach also facilitated the assessment of the moderating effects of personality traits and mediating effects of POS, offering a nuanced understanding of how these variables interact with workplace ostracism to influence individual work performance.

Data Analysis and Measurement Models

Reliability and Validity of Constructs

The high Cronbach’s Alpha values for WOS (0.922), POS (0.901), PI (0.914), and IWP (0.945) confirm the robustness and internal consistency of the measurement scales used. These values exceed the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7, indicating excellent reliability and providing a solid foundation for subsequent analyses.

Correlation Analysis: Significant negative correlations between WOS and IWP components suggest that workplace ostracism adversely affects both contextual performance (CP) and counterproductive work performance (CWP). This aligns with the conservation of resources theory, which posits that ostracism depletes emotional and cognitive resources, thereby impairing performance. Additionally, the inverse relationship between WOS and POS dimensions indicates that higher levels of perceived organizational support can mitigate the negative effects of workplace ostracism, supporting the buffering hypothesis of social support theory. The significant correlations between WOS and PI factors, particularly resilience and emotional stability, suggest that certain personality traits may moderate the impact of ostracism on work outcomes.

These findings underscore the importance of fostering supportive work environments and promoting resilient personality traits to mitigate the adverse effects of workplace ostracism on individual work performance.

These insights are supported by studies examining the moderating effects of individual differences on workplace dynamics. For instance, research has explored how perceived organizational support can moderate the relationship between workplace ostracism and job performance, and how self-esteem levels can influence the impact of workplace ostracism on job performance.

Regression Analysis: WOS and IWP

The regression analysis revealed that all WOS dimensions significantly predict IWP, with the strongest effects observed for "Others refusing to talk to you at work" (B=0.140, β=0.193) and "Others treating you as if you weren’t there" (B=0.130, β=0.181). The high R² value of 0.963 indicates that WOS predictors account for 96.3% of the variance in IWP, emphasizing the substantial impact of ostracism behaviors on workplace performance. The absence of multicollinearity among predictors (VIF < 10) further confirms the model's reliability Tables 1-3.

| Table 1 Model Fit Statistics of WOS and IWP | ||||||||

| Coefficientsa | ||||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity Statistics | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | -1.522 | .033 | -46.350 | .000 | |||

| Others ignored you at work. | .041 | .012 | .057 | 3.510 | .000 | .255 | 3.929 | |

| Others left the area when you entered | .039 | .011 | .049 | 3.397 | .001 | .313 | 3.192 | |

| Your greetings have gone unanswered at work | .057 | .013 | .078 | 4.304 | .000 | .198 | 5.040 | |

| You involuntarily sat alone in a crowded lunchroom at work | .082 | .012 | .110 | 7.129 | .000 | .275 | 3.630 | |

| Others avoided you at work | .069 | .012 | .095 | 5.914 | .000 | .258 | 3.874 | |

| You noticed others would not look at you at work | .087 | .011 | .128 | 8.035 | .000 | .260 | 3.843 | |

| Others at work shut you out of the conversation | .057 | .012 | .072 | 4.848 | .000 | .298 | 3.360 | |

| Others refused to talk to you at work | .140 | .012 | .193 | 11.996 | .000 | .254 | 3.941 | |

| Others at work treated you as if you weren’t there | .130 | .011 | .181 | 11.290 | .000 | .257 | 3.896 | |

| Others at work did not invite you or ask you if you wanted anything when they went out for a coffee break | .076 | .010 | .111 | 7.282 | .000 | .282 | 3.541 | |

| You have been included in conversations at work (reverse coded) | .055 | .010 | .079 | 5.535 | .000 | .324 | 3.084 | |

| Others at work stopped talking to you | .069 | .011 | .098 | 6.524 | .000 | .294 | 3.396 | |

| You had to be the one to start a conversation to be social at work | .062 | .011 | .083 | 5.858 | .000 | .326 | 3.068 | |

| Table 2 Moderation Effect of POS on WOS and IWP Score | ||||||||

| Variable | WOS Coefficient | WOS p-value | WOSxPOS Coefficient | WOSxPOS p-value | POSScore Coefficient | POSScore p-value | R-squared | Adj. R-squared |

| WOS2 | 0.1665 | 0.002 | -0.0396 | 0.014 | 0.8909 | 0.000 | 0.773 | 0.771 |

| WOS5 | 0.2153 | 0.000 | -0.0390 | 0.018 | 0.8409 | 0.000 | 0.777 | 0.776 |

| WOS9 | 0.1717 | 0.001 | 0.0354 | 0.007 | 0.4257 | 0.000 | 0.871 | 0.871 |

| WOS10 | 0.0982 | 0.031 | 0.0452 | 0.000 | 0.4516 | 0.000 | 0.876 | 0.876 |

| WOS13 | 0.0823 | 0.090 | 0.0221 | 0.106 | 0.6453 | 0.000 | 0.809 | 0.808 |

| Table 3 Moderation Effect of PI on WOS and IWP | ||||||||

| WOS Variable | WOS Coefficient | WOS p-value | PIScore Coefficient | PIScore p-value | WOSxPI Coefficient | WOSxPI p-value | R-squared | Adj. R-squared |

| WOS7 | 0.1851 | 0.037 | 0.3591 | 0.00 | 0.0544 | 0.016 | 0.785 | 0.784 |

| WOS8 | 0.0469 | 0.489 | 0.1846 | 0.00 | 0.098 | 0.00 | 0.842 | 0.841 |

| WOS9 | 0.0682 | 0.320 | 0.2347 | 0.00 | 0.0872 | 0.00 | 0.836 | 0.835 |

| WOS10 | 0.0036 | 0.955 | 0.2918 | 0.00 | 0.0896 | 0.00 | 0.812 | 0.811 |

| WOS11 | 0.1456 | 0.053 | 0.4225 | 0.00 | 0.0501 | 0.008 | 0.791 | 0.79 |

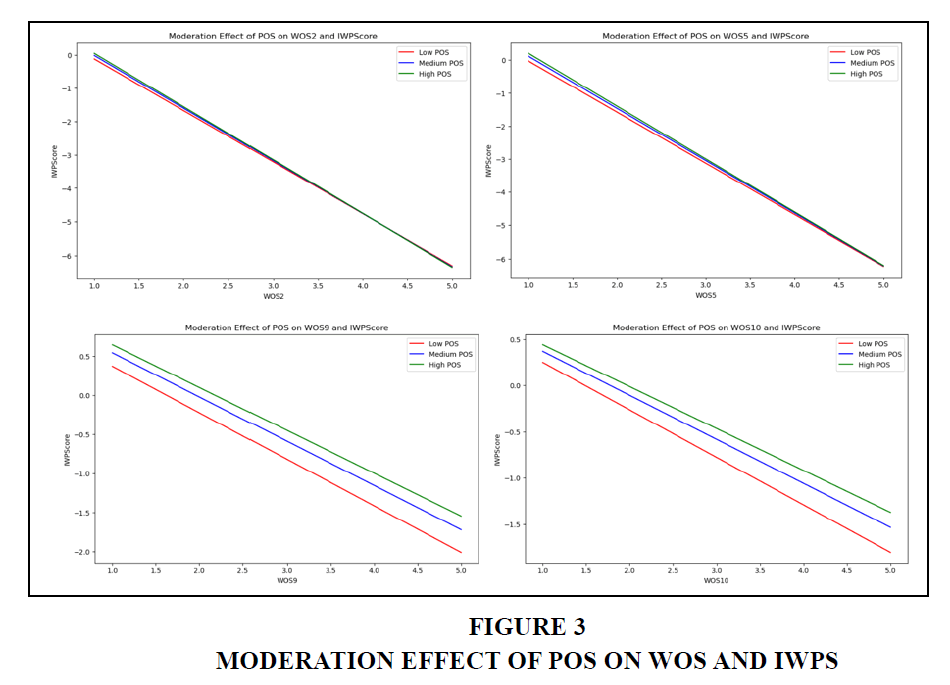

Moderation Analysis: POS as a Buffer

The moderation analysis supported H3, showing that Perceived Organizational Support (POS) significantly moderates the relationship between Workplace Ostracism (WOS) and Individual Work Performance (IWP).

Research indicates that workplace ostracism (WOS) and perceived organizational support (POS) significantly interact to influence individual work performance (IWP). For certain WOS dimensions, such as WOS2 and WOS5, negative interaction effects were observed. Specifically, the interaction between WOS2 and POS (β = −0.0396, p < 0.05) demonstrated that higher POS levels can mitigate the adverse impact of ostracism on performance. This aligns with the social support theory's buffering hypothesis, suggesting that perceived support enables individuals to better cope with workplace challenges like exclusion.

Conversely, for other WOS dimensions, such as WOS9 and WOS10, positive interaction effects were noted. In these cases, higher POS levels intensified the relationship between IWP and ostracism (e.g., β=0.0354, p<0.05). This implies that, under certain conditions, POS may exacerbate the effects of ostracism, potentially motivating employees to enhance their performance or develop resilience to counteract exclusion.

These findings underscore the complex role of POS in the workplace. While it can buffer the negative effects of ostracism in some contexts, it may also amplify its impact in others. Therefore, organizations should strive to create supportive environments that not only reduce the detrimental effects of ostracism but also harness its potential to foster employee growth and resilience.

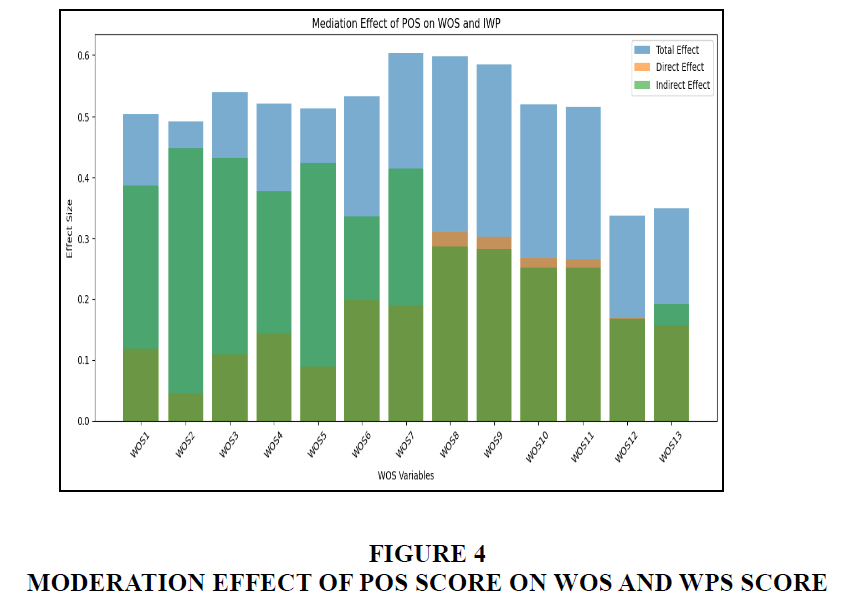

Mediation Analysis: POS as a Mediator

The mediation analysis demonstrated that POS partially or fully mediates the relationship between Workplace Ostracism (WOS) and Individual Work Performance (IWP), providing further support for H3.

The mediation analysis revealed that POS partially or fully mediates the relationship between WOS and IWP. The high fraction mediated for dimensions such as WOS2 (90.87%), WOS3 (79.87%), and WOS5 (82.68%) suggests that POS is responsible for a significant portion of the association between these types of ostracism and job performance. This highlights the importance of fostering organizational support to buffer the adverse effects of workplace ostracism on individual work performance.

Moderation Analysis: Personality Traits

The analysis partially supported H2, showing that personality traits moderate the relationship between WOS and IWP in specific contexts.

The analysis partially supported the hypothesis that personality traits moderate the relationship between WOS and IWP in specific contexts. Significant interaction effects were noted for WOS7 and WOS11, indicating that personality traits may either increase or decrease the negative impacts of ostracism on performance. These findings suggest that individual differences play a crucial role in how workplace ostracism affects work outcomes.

Results Interpretation

Direct Effects: The analysis revealed a direct effect of workplace ostracism (WOS) on individual work performance (IWP), with a path coefficient of 0.469. This indicates a moderately strong and statistically significant relationship, suggesting that higher workplace ostracism is associated with a notable decrease in individual work performance.

Indirect Effects: The indirect effect of workplace ostracism (WOS) on individual work performance (IWP) via perceived organizational support (POS) was found to be 0.364. This result highlights the mediating role of perceived organizational support in the WOS-IWP relationship. It suggests that part of the influence of workplace ostracism on individual work performance occurs indirectly through its impact on perceived organizational support. Managers should focus on enhancing perceived organizational support to counteract the detrimental effects of workplace ostracism. Training programs or policies that promote inclusivity and address ostracism may improve individual work performance.

Moderation Effects: The interaction term for workplace ostracism and personality traits (WOS × PI) on individual work performance (IWP) yielded a path coefficient of -0.008. This indicates a negligible moderation effect, suggesting that personality traits do not significantly alter the relationship between workplace ostracism and individual work performance.

Combined Interpretation: The findings suggest that workplace ostracism negatively impacts individual work performance both directly and indirectly. The mediating effect of perceived organizational support explains a substantial portion of this relationship, emphasizing the importance of fostering organizational support to buffer the adverse effects of ostracism. The moderation analysis revealed that personality traits do not significantly influence this relationship, implying that the impact of ostracism on work performance is relatively consistent across different personality profiles.

Discussion

The studies emphasize that workplace ostracism significantly impairs job performance by increasing employees' psychological stress and emotional exhaustion. This often leads to reduced innovation and workplace deviance, highlighting the critical need for organizations to address this issue proactively. Research suggests that organizational support systems, such as perceived organizational support (POS), play a vital role in mitigating the negative effects of ostracism, enabling employees to perform effectively even under challenging conditions.

To address workplace ostracism, organizations must implement comprehensive training programs aimed at educating employees and managers about its signs, consequences, and strategies for resolution. These programs should promote inclusivity and equip managers with the tools to identify and address ostracism early, fostering healthier workplace dynamics. Furthermore, HR managers have a pivotal role in proactively combating workplace ostracism by establishing clear policies, anonymous reporting mechanisms, and mentorship programs that encourage collaboration and strengthen interpersonal connections.

Incorporating personality inventory assessments into recruitment and selection processes can also be beneficial. These assessments help identify candidates with higher emotional intelligence and resilience, which can reduce the likelihood of ostracism and enhance workplace harmony. Additionally, senior managers must lead by example, cultivating a culture of inclusivity and periodically reviewing the effectiveness of organizational support systems to address any gaps. Collectively, these strategies can help mitigate the adverse effects of workplace ostracism while enhancing employee well-being and overall organizational performance.

Methodological Considerations and Future Directions

The study's methodological concerns highlight how crucial it is to choose reliable frameworks and instruments to investigate the complex impacts of workplace exclusion on workers' productivity and well-being. To ensure dependability, validated scales were used to quantify the mediating influence of psychological resilience and the moderating effect of perceived organizational support (POS). Potential drawbacks like sample diversity should be addressed in future studies since more diverse demographic and cultural representations may improve the findings' generalisability. To gain a deeper understanding of the causal linkages between ostracism, POS, and employee outcomes over time, longitudinal designs are also advised. The relationship between workplace dynamics and organizational actions may be further clarified by extending the discussion of personality traits and utilizing sophisticated analytical techniques like structural equation modeling. Practical implications also point to the need for refining recruitment strategies and support mechanisms, which should be explored through experimental and field studies.

Summary of Theoretical Contribution

Based on the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, the study makes a substantial theoretical contribution to our knowledge of workplace ostracism and its effects on individual work performance (IWP). It has been demonstrated that workplace exclusion drains emotional and cognitive reserves, which are necessary to maintain performance levels (Hobfoll, 1989). The study emphasizes how personality qualities like emotional stability and resilience can act as a mediators to lessen the negative consequences of being shunned. For example, in line with earlier research, more resilient employees can better withstand the psychological effects of exclusion (Ferris et al., 2008).

The study also emphasizes the moderating role of perceived organizational support (POS), which acts as a resource bank to offset the stressors brought on by exclusion. High levels of POS were found to lessen the negative association between ostracism and performance, which is consistent with the findings of Eisenberger et al. (1986). This highlights the significance of a supportive organizational climate. Future interventions aiming at creating inclusive workplace environments and improving performance will be made possible by the integration of these categories, which provides a detailed knowledge of how organizational and individual resources interact to influence outcomes.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has some limitations that should be noted, even if it provides insightful information about how workplace ostracism (WOS) affects individual work performance (IWP). First, due to the cross-sectional research methodology, it is difficult to prove a causal link between personality traits, perceived organizational support (POS), and work-related stress (WOS). A more thorough grasp of causality and temporal dynamics may be possible in future research using longitudinal designs (Hobfoll, 1989). Furthermore, even with efforts to reduce it using statistical controls like Harman's single-factor test, using self-reported measures for WOS and IWP raises the possibility of common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

The findings may not be as applicable to other industries and cultural situations because the sample was limited to medium-sized IT companies in South India. The study's usefulness might be improved by broadening its scope to encompass other industries and global contexts. Future research should examine additional potential moderators, such as organizational climate or emotional intelligence, even if the study incorporates personality traits and POS as mediating and moderating variables (Eisenberger et al., 1986). Finally, qualitative techniques could supplement the study's quantitative methodology to better understand the actual experiences of ostracised personnel. By combining qualitative and quantitative data, future studies could offer a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon, opening the door for more focused interventions to promote resilience and inclusivity in the workplace.

Managerial Implications

The findings of the study highlight how important managers and organizational leaders are in reducing the negative consequences of workplace ostracism (WOS). To address the negative effects of ostracism, such as decreased job performance and increased turnover intentions, managers should place a high priority on creating an inclusive and encouraging organizational culture. According to research, ostracism saps workers' psychological reserves, which lowers involvement and output (Leung, 2011). Managers can mitigate these effects by putting in place training programs designed to raise awareness of the subtle signs of ostracism and its long-term repercussions on organizational outcomes and employee well-being (Wang, 2023). To foster empathy, enhance communication, and set up procedures for recognizing and dealing with exclusionary behaviors, such training ought to be directed at both supervisors and employees.

Incorporating strong support networks, like mentorship programs and mental health resources, can also give staff members ways to get assistance if they feel alone. Managers can improve team cohesiveness and lessen cases of isolation at work by aggressively combating ostracism through frequent feedback channels and encouraging candid communication (Li, 2021).

The incorporation of perceived organisational support (POS) efforts is another crucial managerial aspect. According to Mohammad, & Nazir, (2023), POS has been demonstrated to mitigate the negative impacts of ostracism on performance, highlighting the necessity for managers to show concern for the contributions and welfare of their staff. A workplace that reduces social exclusion and increases productivity can be achieved by establishing explicit anti-ostracism rules, promoting inclusivity, and upholding fair treatment norms.

Conclusion

This study emphasises how personality factors and perceived organisational support (POS) attenuate the significant effects of workplace exclusion on individual work performance. The results support the theory that ostracism at work saps workers' emotional and mental reserves, which lowers job performance. These negative impacts were shown to be exacerbated by low emotional stability and strong sensitivity to rejection, while they were lessened by personality qualities including conscientiousness and resilience. Furthermore, the moderating function of POS emphasises how crucial it is to create a positive work atmosphere. High POS levels improve employee engagement and resilience while also mitigating the negative impacts of exclusion.

This study's theoretical contributions are found in its integration of empirical data with the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, which highlights the complex relationships among organisational support, personality traits, and ostracism. Practically speaking, the study promotes focused measures including putting in place inclusive workplace rules, providing training programs based on personality, and making sure that organisational support networks are strong and efficient. By taking these steps, ostracism's negative consequences can be lessened and a positive workplace culture can be promoted. In conclusion, by offering practical advice for academics and professionals alike, this study adds to the expanding corpus of research on workplace exclusion. The study provides a comprehensive framework for enhancing employee performance and well-being in the face of workplace challenges by addressing the intricate interactions between organizational and individual elements.

References

Abbas, M., Raja, U., Darr, W. and Bouckenooghe, D. (2014), "Combined effects of perceived politics and psychological capital on job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and performance", Journal of Management, Vol. 40 No. 7, pp. 1813-1830.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Abubakar, A.M., Chauhan, S. and Kura, K.M. (2018), "Work stress, social support, and withdrawal behavior among Nigerian nurses", Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 202, pp. 104-110.

Bedi, A., 2019. No herd for black sheep: A meta-analytic review of the predictors and outcomes of workplace ostracism. Applied Psychology, 69(2), pp.725-770.

Bryman, A., Bell, E., Mills, A.J. and Yue, A.R. (2015), Business Research Methods, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Chen, Z., Zhang, X. and Vogel, D. (2011), "Exploring the boundary conditions of workplace ostracism", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 96 No. 6, pp. 1237-1248.

Dahiya, R., Singh, A. and Pandey, A., 2024. Exploring the link between workplace relationship conflict and employee ostracism behavior: The roles of relational identification, emotional energy, and perceived forgiveness climate. International Journal of Conflict Management.

De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U. and Azeem, M. U. (2019), “Workplace ostracism and job performance: roles of self-efficacy and job level”. Personnel Review, Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 184-203.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S. and Sowa, D. (1986), “Perceived Organizational Support”. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 71, No. 3, pp. 500–507.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I.L. and Rhoades, L. (2002), "Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87 No. 3, pp. 565-573.

Ferris, D.L., Brown, D.J., Berry, J.W. and Lian, H. (2008), "The development and validation of the workplace ostracism scale", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 93 No. 6, pp. 1348-1366.

Ferris, D.L., Lian, H., Brown, D.J. and Morrison, R. (2015), " Ostracism, self-esteem, and job performance: When do we self-verify and when do we self-enhance?", Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 58 No. 1, pp. 279-297.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fox, S. and Stallworth, L.E. (2005), "Racial/ethnic bullying: Exploring links between bullying and racism in the US workplace", Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 66 No. 3, pp. 438-456.

Hobfoll, S.E., 1989. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), pp.513-524.

Hobfoll, S.E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), pp.337-421.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Howard, M.C., Cogswell, J.E. and Smith, M.B., 2022. Examining the pathways between workplace ostracism and suicidal ideation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(4), pp.400-415.

Jiang, J., Wang, L. and Lin, H., 2020. The moderating effect of perceived organizational support on the relationship between workplace ostracism and job performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(1), pp.7-19.

Kock, N., 2015. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration (ijec), 11(4), pp.1-10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Leung, A. S. M., Wu, L. Z., Chen, Y. Y., & Young, M. N. (2011). The impact of workplace ostracism in service organizations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(4), 836–844.

Liu, C., Kwan, H.K., Lee, C. and Hui, C., 2013. Work-to-family spillover effects of workplace ostracism: The role of work-home segmentation preferences. Human Resource Management, 52(1), pp.75-94.

MacDonald, G. and Leary, M.R., 2005. Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological Bulletin, 131(2), pp.202-223.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Malhotra, N., Sahadev, S. and Purani, K., 2017. Psychological contract violation and customer intention to reuse online retailers: Exploring mediating and moderating mechanisms. Journal of Business Research, 75, pp.17-28.

Mohammad, S. S., & Nazir, N. A. (2023). Practical implications of workplace ostracism: A systematic literature review. Business Analyst Journal, 44(1), 15–33.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rammstedt, B. and John, O. P. (2007), “Measuring Personality in One Minute or Less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German”, Journal of Research in Personality, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 203–212.

Rudert, S.C., Hales, A.H., Greifeneder, R. and Williams, K.D., 2020. Ostracism in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(9), pp.1131-1149.

Sharma, R. and Tiwari, P., 2022. Stress at work in the IT sector: Trends and challenges in the Indian context. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 13(1), pp.1-21.

Smith, A. and Williams, K.D., 2004. R U There? Ostracism by cell phone text messages. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 8(4), pp.291-301.

Wang, L. M., Lu, L., Wu, W. L., & Luo, Z. W. (2023). Workplace ostracism and employee wellbeing: A conservation of resource perspective. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, Article 1075682.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Williams, L. J., Vandenberg, R. J. and Edwards, J. R. (2009), “12 structural equation modeling in management research: A guide for improved analysis”, Academy of Management Annals, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 543-604.

Yaakobi, E. (2019), “Fear of death mediates ostracism distress and the moderating role of attachment internal working models”, European Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 645-657.

Zhao, H., Peng, Z. and Sheard, G. (2013). Workplace ostracism and hospitality employees' counterproductive work behaviors: The joint moderating effects of proactive personality and political skill. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 219-227.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 14-May-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-15929; Editor assigned: 15-May-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-15929(PQ); Reviewed: 10-Jun-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-15929; Revised: 26-Jun-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-15929(R); Published: 14-Jul-2025