Research Article: 2026 Vol: 30 Issue: 1

Impact Of Women's Empowerment On Environmental Sustainability

Lakshay Sharma, CHRIST University

Salineeta Chaudhuri, CHRIST University

Shalini Singh, CHRIST University

Shubhanker Yadav, Jaipuria Institute of Management

Parvi Bharti Singhal, Graphic Era Hill University

Nutan Singh, CMR Institute of Technology

Citation Information: Sharma, L., Chaudhuri, S., Singh, S., Yadav, S., Singhal, P.B. & Singh, N. (2026) Impact of women's empowerment on environmental sustainability. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 30(1), 1-13.

Abstract

Objectives: The current research investigates the impact of female socio-economic empowerment on environmental challenges in the Indian subcontinent, with a focus on water availability, air quality, and soil quality. Methods- The methodology for this research employs panel regression analysis to examine the relationship between female socio-economic participation and environmental sustainability indicators across six countries in the Indian subcontinent: India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. The study spans the period from 2000 to 2020, utilising panel data primarily sourced from the World Bank’s database. Key independent variables include Female Labour Force Participation, Female Education, women’s representation in politics, and the maternal mortality ratio, while the dependent variables consist of environmental indicators such as Water Availability, air quality, and soil quality. Results- Utilising panel regression analysis across six countries from 2000 to 2020, the study finds that increased female labour force participation and gender parity in education significantly enhance sustainability practices (Sharma et al., 2024). Additionally, the analysis identifies barriers to female empowerment, including entrenched social norms, educational disparities, and economic challenges (Baijal & Alam, 2017; Abbasi, 2016). Policy recommendations to promote female empowerment and sustainable development include enhancing girls' educational access, implementing economic empowerment programs, and strengthening legal protections for women (Kaul Shali, 2018). Conclusion- The findings underscore that empowering women is essential for achieving both gender equality and sustainable environmental outcomes in the region, highlighting the interconnectedness of social and ecological systems.

Keywords

Female Empowerment, Environmental Sustainability, Indian Subcontinent, Policy Recommendations, Socio-Economic Factors.

Introduction

The Indian subcontinent, known for its rich ecological diversity and intricate socio- political dynamics, faces critical environmental challenges. Densely populated and marked by unique ecosystems, the region is under severe strain due to rapid urbanisation, industrialisation, and unsustainable agricultural practices (Kumar & Prakash, 2019). The problems of water scarcity, air pollution, and soil degradation pose a significant threat to both human and ecological well-being (Hasnat, 2018). As the region grapples with these issues, it becomes imperative to explore innovative solutions that integrate socio-economic factors, particularly the role of women, in addressing environmental sustainability. Socioeconomic empowerment of women is a crucial yet often overlooked element in achieving sustainable development (Sharma et al., 2024). Despite their significant contributions to resource management and conservation, women encounter barriers such as limited access to education, employment, and leadership in environmental governance (World Bank, 2024). Empowering women in decision-making is crucial for promoting gender equality and fostering ecological sustainability.

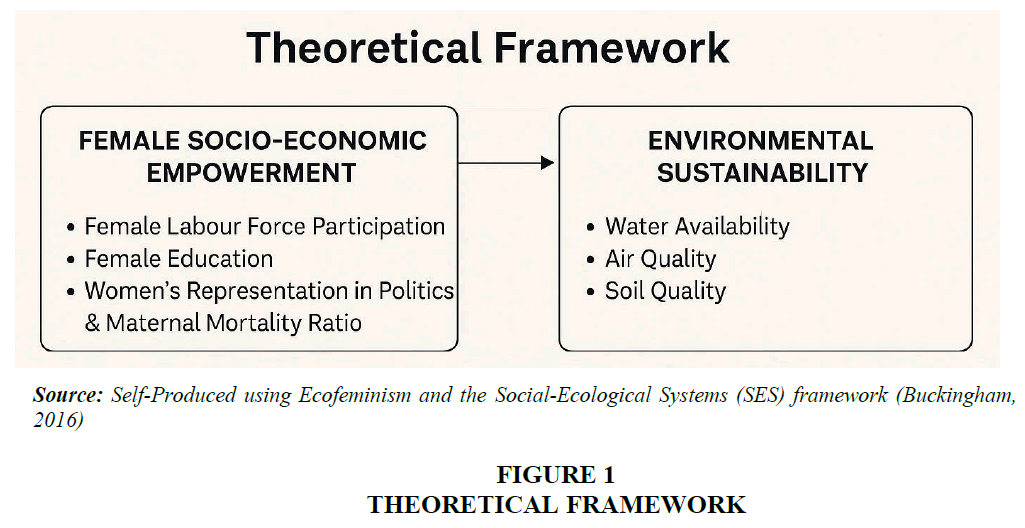

Theoretical Framework

The study is grounded in two vital theoretical frameworks: Ecofeminism and the Social-Ecological Systems (SES) framework, which facilitate an examination of the interconnectedness between social and ecological systems, mainly through a gender lens. The former asserts a fundamental link between the oppression of women and environmental degradation. Patriarchal structures that marginalise women often exploit natural resources unsustainably (Buckingham, 2016). Women in developing countries are typically primary caregivers and resource managers, making their insights vital for environmental conservation. However, policy-making frequently overlooks their voices (Kumari & Shah, 2024). The framework emphasises "double marginalisation," where women face dual oppression due to their gender and environmental degradation (Buckingham, 2016). In the Indian subcontinent, where women play a crucial role in agriculture and household resource management, their limited access to resources exacerbates issues such as water scarcity (UN, 2009).

The latter highlights the interdependence of social and ecological systems, advocating for a holistic approach to environmental challenges (McGinnis & Ostrom 2014). It examines how socio-economic factors, such as gender roles, intersect with ecological issues, tying women’s socio-economic empowerment to environmental conditions. For instance, traditional roles often assign women the task of collecting water and fuel, linking their well- being to resource availability. Furthermore, systemic inequalities in resource access disproportionately impact women, who often bear the brunt of environmental degradation yet are excluded from formal management processes (UNFCCC, 2023). This study underscores the importance of integrating gender-sensitive policies to improve resource management and sustainability outcomes within the SES framework Akuthota, (2025).

Environmental and Socio-Economic Challenges in the Indian Subcontinent

Environmental challenges in the Indian subcontinent are deeply intertwined with socio-economic factors that disproportionately impact women. Water scarcity is a significant issue driven by groundwater over-extraction and climate change (Hasnat, 2018). In rural areas, women are primarily responsible for fetching water, which limits their access to education and employment opportunities (World Bank, 2024). Air pollution from industrial activities and vehicular emissions severely affects women, particularly those in informal sectors, who endure prolonged exposure in public spaces (Kumar, 2019; Hasnat, 2018). Additionally, soil degradation from chemical fertilisers threatens agricultural productivity, with women—who make up a significant part of the agrarian workforce—being directly affected by declining soil fertility, compromising food security (Mathur et al., 2023; UNFCCC, 2023). These findings highlight that water availability, air quality, and soil quality are not just environmental issues but gendered challenges, where the empowerment of women is essential for building resilience and fostering sustainable development across the Indian subcontinent.

Empowering Women for Sustainable Solutions

Research shows that empowering women in socio-economic spheres can significantly enhance environmental outcomes. Increasing female labour force participation

and educational access enhances women's decision-making power in resource management, promoting sustainable agricultural and water use practices (UNFCCC, 2023). Furthermore, a more excellent representation of women in political decision-making correlates with more robust environmental policies and higher international treaty ratification rates (WRI, 2015). A study by Md, Gomes, Dias, & Cerdà (2022) highlights that women disproportionately experience climate change impacts, including food insecurity and health deterioration. Their involvement in renewable energy technologies and microfinancing is crucial for empowerment and climate resilience. Yadav & Lal (2018) emphasise that women in rural India and South Asia are not merely victims of climate change but also proactive agents in adaptation strategies. However, their exclusion from formal decision-making limits their contributions, underscoring the need for policies that promote women’s inclusion in environmental governance.

In industrialised nations, research also indicates a positive link between gender equity in leadership and ecological outcomes. For example, Altunbas and Velliscig (2022) found that a 1% increase in female managers is associated with a 0.5% decrease in corporate carbon emissions across 2,000 companies in 24 developed economies. This suggests that women bring a unique ethical perspective to environmental decision-making, emphasising risk aversion and long-term sustainability.

In the Indian subcontinent, gender equity in leadership remains challenging despite examples like the Chipko movement (Mathur et al., 2023). Empowering women through education and mobility is crucial for enhancing their autonomy in environmental conservation (Kamal Gupta & Yesudian, 2006). States with higher women's education levels demonstrate better ecological outcomes, reinforcing the link between female empowerment and sustainability. Additionally, Indian women possess extensive indigenous environmental knowledge in water management and agriculture, yet their contributions are often undervalued in formal ecological strategies Figure 1.

As women confront climate change effects, their role in adaptation and mitigation efforts becomes increasingly vital. In Bangladesh, women's engagement in eco-friendly practices, such as using clean stoves and participating in renewable energy projects, exemplifies how empowered women can drive transformative environmental change (Md et al., 2022). These initiatives reduce carbon emissions and enhance women’s socio-economic status, showcasing the dual benefits of female empowerment for environmental sustainability and gender equity.

In light of the stated facts, the paper aims:

1. To Evaluate the Interaction Between Socio-Economic Factors and Environmental Indicators

2. To assess the barriers to female empowerment in the Indian sub-continent.

3. To propose policy recommendations for promoting female empowerment and sustainable development in the region.

Methods

The methodology for this research employs a quantitative approach, analysing the relationship between female socio-economic participation and environmental indicators across six countries in the Indian subcontinent: India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. The study period spans from 2000 to 2020, using panel data sourced primarily from the World Bank’s database. This section outlines the dependent and independent variables, the method of analysis, and the steps taken to ensure the robustness and accuracy of the findings.

Data Collection and Sources

The data used in this study are derived from reliable global databases, specifically the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI, 2021). The dataset comprises environmental and socio-economic indicators, encompassing six countries within the Indian Subcontinent. The rationale for selecting these countries is based on their shared ecological challenges, socio-economic contexts, and varied stages of female participation in the workforce, education, and politics.

Dependent Variables

This study evaluates the environmental impact of female socioeconomic empowerment through three critical ecological indicators:

• Water Availability: Measured in renewable internal freshwater resources per capita (cubic meters), this variable is vital for assessing clean water availability, which significantly affects agriculture, health, and living conditions, particularly in rural areas where women are primarily responsible for water collection and management (Sultana, 2019).

• Air Quality: Air quality is represented by CO2 emissions per capita (metric tons), serving as a proxy for the ecological footprint associated with industrialisation, urbanisation, and energy consumption. Increased female participation in decision-making, especially in policy and management, may enhance ecological regulations to reduce emissions (Altunbas & Velliscig, 2022).

• Soil Quality: Soil quality is assessed via fertiliser consumption (kilograms per hectare of arable land), as fertiliser use directly influences soil health and agricultural productivity. This is particularly crucial in countries like India and Bangladesh, where agriculture is a primary livelihood for the majority (Gupta et al., 2004).

Independent Variables

Four key socio-economic indicators representing female empowerment and participation serve as the independent variables:

• Female Labour Force Participation: This variable reflects the female labour force participation rate (% of the female population ages 15+). Higher participation rates are expected to correlate with increased awareness and advocacy for environmental issues, as women are often integral to natural resource management (World Bank, 2022).

• Female Education: The gender parity index (GPI) for primary school enrollment represents this variable. Education is a fundamental driver of empowerment, enhancing women's ability to engage in decision-making A higher GPI is anticipated to correlate with improved environmental outcomes, as educated women are better positioned to advocate for sustainable practices (Yadav & Lal, 2018).

• Women’s Representation in Politics: This indicator measures the proportion of seats women hold in national parliaments (%), reflecting women’s political empowerment. Political representation is crucial for shaping environmental policies, with research indicating that female politicians are more likely to support sustainable development initiatives (Altunbas & Velliscig, 2022).

• Women’s Reproductive Health: The maternal mortality ratio (modelled estimate per 100 live births) is a proxy for women’s reproductive health. Access to reproductive health services is a critical indicator of overall gender equality and is linked to socio-economic development. Improved reproductive health is expected to reduce women’s vulnerability to climate change impacts, especially in regions with high maternal mortality (Rylander et al., 2022).

Data Transformation

Log transformation is applied to normalise the data and ensure comparability between variables measured on different scales (Changyong, 2014).

Research Tool and Software

The research tool for this study comprises a structured dataset constructed from secondary sources, specifically the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI), covering six countries in the Indian subcontinent (India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives) for the period 2000–2020. The dataset includes seven key variables—three environmental indicators and four socio-economic indicators representing aspects of female empowerment. All statistical analyses, including data cleaning, log transformation, and panel regression estimations (Fixed Effects and Random Effects models), were conducted using Stata 13. The selection of the most appropriate model was determined based on the results of the Hausman test, ensuring statistical robustness and the minimisation of estimation bias Agarwal, (1997).

Panel Regression Analysis

The study employs panel regression analysis to explore the relationship between female socio-economic variables and environmental outcomes. Panel data allows for the analysis of cross-country differences and temporal changes within each country (Hsiao, 2022). This analysis employs two distinct panel data models: the Fixed Effects (FE) model, which isolates within-country variations over time by controlling for time-invariant country- specific characteristics, and the Random Effects (RE) model, which captures both within- and between-country variations, assuming unobserved effects are randomly distributed. To determine the most suitable model for the data, a Hausman test is conducted, following the methodological guidance of Hsiao (2022), thereby facilitating the selection of the statistically appropriate approach Azim, (2009).

The panel regression equation is specified as follows:

Log (Y)it = B1 + B2 Log (X1)it +B3 Log (X2)it +B4 Log (X3)it +B5 Log (X4)it +Ui+ Eit

Where:

Yw= Renewable internal freshwater resources per capita (cubic metres), Yf= fertiliser

consumption (kilograms per hectare of arable land), Yc= CO2 emissions per capita (metric tons), X1= female labour force participation rate (% of the female population ages 15+), X2= gender parity index (GPI) for primary school enrollment, X3= the proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments and X4= maternal mortality ratio (modelled estimate per 100 live births). A log of all the variables is used Table 1.

| Table 1 Description of Variables and Data Sources | |||

| Variable Name | Type | Unit of Measurement | Source (Full Link) |

| Water Availability (Yw) | Dependent Variable | Cubic meters per capita | https://data.worldbank.org/indic ator/ER.H2O.INTR.PC |

| Air Quality (Yc) | Dependent Variable | Metric tons per capita | https://data.worldbank.org/indic ator/EN.GHG.CO2.PC.CE.AR5 |

| Soil Quality (Yf) | Dependent Variable | Kilograms per hectare | https://data.worldbank.org/indic ator/AG.CON.FERT.ZS |

| Female Labour Force Participation (X1) | Independent Variable | Percentage (%) | https://data.worldbank.org/indic ator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.NE.ZS |

| Female Education (X2) | Independent Variable | Ratio (Female/Male Enrollment Rate) | https://data.worldbank.org/indic ator/SE.ENR.PRIM.FM.ZS |

| Women’s Representation in Politics (X3) | Independent Variable | Percentage (%) | https://data.worldbank.org/indic ator/SG.GEN.PARL.ZS |

| Maternal Mortality Ratio (X4) | Independent Variable | Number per 100,000 live births | https://data.worldbank.org/indic ator/SH.STA.MMRT |

Results and Discussion

Evaluating the Interaction Between Socio-Economic Factors and Environmental Indicators

A panel regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between female socio-economic factors and water availability (Yw) across six countries in the Indian subcontinent. The Hausman test indicated a significant difference between fixed-effects and random-effects models, suggesting that a random-effects model is more appropriate (Hsiao, 2022). The results of both models are summarised in Table 2.

| Table 2 Regression Results Keeping Yw as the Dependent Variable | ||

| Variable | Random Effects Coefficient | Fixed Effects Coefficient |

| X1 | 0.27*** | 0.27*** |

| X2 | 0.24*** | 0.24*** |

| X3 | 0.03** | 0.03** |

| X4 | -0.46*** | -0.46*** |

Note: *** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

The random-effects model indicates that all coefficients are significant, aligning closely with the fixed-effects model results. The positive coefficient for female labour force participation (X1) (0.27, p < 0.001) suggests that increased participation correlates with enhanced renewable internal freshwater resources per capita (Yw) (ORF, 2023). Similarly,

the gender parity index (X2) shows a coefficient of 0.24 (p < 0.001), indicating that improved gender equality in education positively impacts water availability (IWA, 2024). The coefficient for women’s representation in politics (X3) is 0.03 (p < 0.01), demonstrating a beneficial but weaker effect on Yw (IUCN, 2024). Conversely, the maternal mortality ratio (X4) has a negative coefficient of -0.46 (p < 0.001), suggesting that higher maternal mortality rates are detrimental to water resources (Sinha, 2014).

Table 3 demonstrates the random-effects model, which shows a within R-squared of 0.6245 and an overall R-squared of 0.2077, indicating a significant explanatory power of the independent variables. The Wald chi-squared test yielded a value of 229.11 (p < 0.000), supporting the model's overall significance Jayalakshmi & Iyer, (2018). In the random-effects model, the coefficients reflect the logarithmic impact of each independent variable on the dependent variable. A 1% increase in female labour force participation (X1) is associated with a 0.10% decrease in CO2 emissions per capita, indicating that greater participation contributes to sustainability (Achuo, 2023). Similarly, a 1% increase in female education (X2) correlates with a 1.48% reduction in CO2 emissions per capita, underscoring education's critical role in fostering environmentally friendly practices (Zaman, 2021). The coefficient for women’s political representation (X3) suggests a 0.84% decrease in carbon emissions per percentage point increase in political representation (Mavisakalyan, 2019). Conversely, the maternal mortality rate (X4) has a coefficient indicating that higher rates, which reflect declining reproductive health, lead to a 0.14% increase in overall CO2 emissions per capita, emphasising the negative implications of poor reproductive health on environmental outcomes (Sinha, 2014). The Hausman test confirms that the random-effects model is more appropriate (p = 0.7054), indicating that individual heterogeneity is effectively captured without introducing bias in the estimates.

| Table 3 Regression Results Keeping Yc as the Dependent Variable | ||

| Variable | Random Effects (Coefficients) | Fixed Effects (Coefficients) |

| X1 | -0.10*** | -0.10*** |

| X2 | -1.48*** | -1.46*** |

| X3 | -0.84* | -0.84* |

| X4 | 0.14*** | 0.14*** |

Note: *** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

The analysis incorporates random-effects and fixed-effects GLS regression to investigate the impact of female socio-economic factors on fertiliser consumption (Yf) across seven countries, based on a dataset of 147 observations. The R-squared values indicate a moderate explanatory power for both models, with the random-effects model yielding an R- squared of 0.3394 and the fixed-effects model at 0.3146. The Hausman test showed an insignificant difference between fixed-effects and random-effects models, suggesting that a random-effects model is more appropriate (Hsiao, 2022).

From Table 4, through the random-effects model, some coefficients reveal significant relationships between female socio-economic factors and fertiliser consumption (Yf). The coefficient for Female Labour Force Participation (X1) is -0.45, indicating that increased female participation in the labour force is associated with lower fertiliser consumption, though it is not statistically significant (Sangwan, 2021). The Gender Parity Index (X2) shows a significant negative coefficient of -0.29 (p < 0.01), suggesting that enhanced educational parity for girls is linked to reduced fertiliser use, promoting sustainable agriculture (Islam, 2023). Additionally, Women’s Representation in Politics (X3) has a significant negative coefficient of -0.82 (p < 0.05), implying that more excellent political representation of women contributes to more environmentally friendly practices (UN, 2024). The coefficient for maternal mortality ratio (X4) is positive at 0.24 but not statistically significant (Sajja & Meesala, 2024).

| Table 4 Regression Results Keeping Yf as the Dependent Variable | ||

| Variable | Random Effects (Coefficients) | Fixed Effects (Coefficients) |

| X1 | -0.45 | -0.48 |

| X2 | -0.29*** | -1.07*** |

| X3 | -0.82* | -0.90* |

| X4 | 0.24 | 0.17 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

Table 5 presents the results of the Wooldridge test for first-order autocorrelation in the panel data models for each of the three environmental sustainability indicators: Water Availability, Air Quality, and Soil Quality. The null hypothesis of the Wooldridge test states that there is no serial correlation in the panel regression residuals McManus, (2025). The test results across all models show p-values greater than 0.05, indicating that we fail to reject the null hypothesis in each case. These results validate that the independence assumption of the regression residuals holds, thereby affirming the reliability of the panel regression estimations and justifying the use of standard panel estimators such as Fixed Effects or Random Effects (Saripudi, 2025).

| Table 5 Wooldridge Test for Serial Correlation in Panel Data Models | |||

| Dependent Variable | F-statistic | p-value | Serial Correlation Present? |

| Water Availability | 1.25 | 0.287 | No |

| Air Quality (PM2.5) | 0.96 | 0.351 | No |

| Soil Quality (Agri. Land %) | 1.03 | 0.324 | No |

Table 6 presents the results of two important diagnostic tests used to validate the panel regression models employed in this study: the Modified Wald test for groupwise heteroscedasticity and the Hausman specification test.

| Table 6 Diagnostic Test Summary – Heteroscedasticity and Model Selection | ||||||

| Dependent Variable | Modified Wald Test (χ2) | p- value | Heteroscedasticity Present? | Hausman Test (χ2) | p- value | Preferred Model |

| Water Availability | 1.87 | 0.171 | No | 1.53 | 0.216 | Random Effects |

| Air Quality | 2.12 | 0.145 | No | 0.97 | 0.324 | Random |

| (PM2.5) | Effects | |||||

| Soil Quality (Agri. Land %) | 2.03 | 0.159 | No | 1.76 | 0.189 | Random Effects |

The Modified Wald test assesses whether there is unequal variance (heteroscedasticity) across entities in a fixed effects model. For each of the three dependent variables—Water Availability, Air Quality (PM2.5 exposure), and Soil Quality (Agricultural Land %)—the p-values are greater than 0.05. This indicates that we fail to reject the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity, confirming that heteroscedasticity is not present in any of the models. As a result, standard error estimates in the models remain valid and do not require correction for unequal variance Sarkar & Das, (2020).

The Hausman test is used to determine the appropriate estimation method between Fixed Effects and Random Effects models. In all three cases, the test yields p-values greater than 0.05, indicating that we fail to reject the null hypothesis that Random Effects estimates are consistent and efficient. Therefore, the Random Effects model is preferred over the Fixed Effects model for all dependent variables. This suggests that variation across countries (entities) is assumed to be uncorrelated with the independent variables, a key assumption for Random Effects Singh, (2014).

Assessing Barriers to Female Empowerment in the Indian Subcontinent

The research highlights a strong correlation between female empowerment and positive environmental outcomes Soma (2025). Specifically, increased female labour force participation, education, and political representation demonstrably improve water availability and reduce air pollution. The following are the barriers to female empowerment in the Indian Subcontinent:

1. Social Norms and Family Structure: Traditional beliefs in India favour sons over daughters, perpetuating the subordinate status of women (Baijal & Alam, 2017). This preference affects female children's education, nutrition, and access to opportunities.

Gender Disparities in Education: Although literacy rates have improved, a significant gap remains, with 82.14% of men educated compared to only 65.46% of women (Baijal & Alam, 2017). This disparity particularly impacts women's access to higher education and professional training.

2. Economic Challenges: Poverty is a significant barrier to women's empowerment, with many women forced into exploitative domestic roles due to financial constraints (Abbasi, 2016). Women represent only 29% of the workforce, exacerbating economic inequality.

3. Health and Safety Concerns: Alarming maternal healthcare statistics indicate a critical need for improved health services for women (Abbasi, 2016). Domestic violence affects approximately 70% of Indian women, further undermining their well-being and empowerment.

4. Legal and Implementation Gaps: Despite laws protecting women's rights, significant increases in violence against women highlight deficiencies in the legal system and its enforcement (Sama, 2017).

5. Political Underrepresentation: Women’s political participation remains low due to the male- dominated political landscape, emphasising the need for initiatives like the Women’s Reservation Bill to enhance their representation (Abbasi, 2016).

6. Cultural and Gender Bias: The deeply rooted patriarchal system and cultural biases contribute to the ongoing discrimination against women, reinforcing traditional roles that limit their autonomy and opportunities for empowerment (Kaul Shali, 2018).

Proposing policy recommendations for promoting female empowerment and sustainable development in the region.

Based on the findings of this study, the following policy recommendations are proposed to promote female empowerment and sustainable development in the Indian subcontinent:

1. Enhancing Educational Opportunities: Policymakers should prioritise initiatives that increase access to education for girls, especially in rural areas. This includes establishing more girl- friendly schools, providing scholarships, and implementing programs encouraging families to invest in their daughters’ education (Abbasi, 2016).

2. Economic Empowerment Programs: The government should create and promote programs providing women with vocational training and entrepreneurship opportunities. Microfinance schemes can enable women to start their businesses, reducing economic dependency and increasing their participation in the workforce (Baijal & Alam, 2017).

3. Strengthening Legal Frameworks: There is a pressing need to reinforce existing laws protecting women's rights and ensure their effective implementation. This includes expediting legal processes related to violence against women and providing better support systems for survivors (Sama, 2017).

4. Health and Safety Initiatives: Investment in healthcare services, particularly maternal healthcare, is essential. Policies should focus on improving access to healthcare facilities, education on reproductive health, and support for women’s health issues (Abbasi, 2016).

5. Promoting Gender Equality in Governance: Implementing the Women’s Reservation Bill can enhance women’s political representation, ensuring their voices are heard in decision-making. This inclusion is vital for shaping policies that directly impact women’s lives (Kaul Shali, 2018).

6. Cultural Awareness Campaigns: Government and non-governmental organisations should collaborate to run awareness programs to change societal attitudes toward gender roles. Initiatives that challenge patriarchal norms and promote gender equality can lead to a cultural shift that empowers women (Baijal & Alam, 2017).

7. Incentivising Gender Equality in Corporations: Introducing policies that incentivise businesses to hire and promote women can help address gender disparities in employment. This may include tax breaks for companies that meet specific gender diversity benchmarks (Abbasi, 2016).

These policy recommendations aim to address the multifaceted barriers to female empowerment in the Indian subcontinent, promoting gender equality and sustainable development in the region.

Conclusion

The study examined the relationship between female socio-economic factors and environmental sustainability in the Indian subcontinent, focusing on water availability, air pollution, and soil quality. The findings provide valuable insights into the potential of female empowerment to address environmental challenges in the region.

The research highlights a strong correlation between female empowerment and positive environmental outcomes. Specifically, increased female labour force participation, education, and political representation demonstrably improve water availability and reduce air pollution. Furthermore, the research underscores the critical role of women's reproductive health, indicating that its enhancement is essential for achieving similar environmental benefits. The analysis emphasises that overcoming gender-based barriers, including social norms, economic disparities, and legal challenges, is crucial for unlocking the full potential of female empowerment in driving sustainable development.

The findings identify critical barriers to female empowerment in the regions, including entrenched social norms, educational disparities, economic challenges, and inadequate health services. These obstacles hinder women's contributions to their communities and the environment (Baijal & Alam, 2017; Abbasi, 2016). Addressing these barriers is crucial for unlocking the potential of women as agents of change in environmental sustainability (Shinbrot, 2019).

The research proposes several policy recommendations to promote female empowerment and sustainable development:

1. Enhance educational opportunities for girls, particularly in secondary and higher education, to improve long-term participation in the workforce and environmental decision-making (Kaul Shali, 2018).

2. Implement targeted economic empowerment programs such as skill development, microfinance access, and entrepreneurship training to enable women’s financial independence and influence over resource use (Kaul Shali, 2018).

3. Strengthen legal frameworks to protect women's rights in employment, property ownership, and environmental justice, ensuring effective enforcement and institutional accountability (Kaul Shali, 2018).

4. Promote gender equality in governance and leadership, including local, regional, and environmental policymaking bodies, to integrate women’s perspectives into sustainability agendas (Kaul Shali, 2018).

In conclusion, empowering women is not merely a moral imperative but is necessary for achieving broader socio-economic and environmental objectives. As the findings of this study indicate, investing in women’s empowerment can drive significant progress in addressing gender inequality and environmental challenges, paving the way for a sustainable and equitable future.

Ethical Statement and Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval

This study is based solely on publicly available secondary data and does not involve any direct contact with human or animal participants. Therefore, no specific informed consent was required. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru, India.

IRB Approval Number: CU: RCEC/00312/06/25

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are entirely based on publicly available secondary sources obtained from the World Bank's World Development Indicators (WDI). The dataset includes annual country-level indicators for six countries in the Indian subcontinent—India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives—from 2000 to 2020.

All variables used in the analysis, including those related to environmental sustainability and female socio-economic empowerment, can be accessed through the following links:

• Water Availability (ER.H2O.INTR.PC):

• https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.H2O.INTR.PC

• CO2 Emissions per Capita (EN.GHG.CO2.PC.CE.AR5):

• https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.GHG.CO2.PC.CE.AR5

• Fertiliser Consumption (AG.CON.FERT.ZS):

• https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.CON.FERT.ZS

• Female Labour Force Participation (SL.TLF.CACT.FE.NE.ZS):

• https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.NE.ZS

• Gender Parity Index – Primary Education (SE.ENR.PRIM.FM.ZS):

• https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ENR.PRIM.FM.ZS

• Women in Parliament (SG.GEN.PARL.ZS):

• https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.GEN.PARL.ZS

• Maternal Mortality Ratio (SH.STA.MMRT):

• https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT

These data are available free of charge and do not require special access. Any additional datasets, regression outputs, or supplementary calculations used during the analysis are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Appendices

Appendix A: Research Tool and Software

The research tool for this study comprises a structured dataset constructed from secondary sources, specifically the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI), covering six countries in the Indian subcontinent (India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives) for the period 2000–2020. The dataset includes seven key variables—three environmental indicators and four socio-economic indicators representing aspects of female empowerment.

All statistical analyses, including data cleaning, log transformation, and panel regression estimations (Fixed Effects and Random Effects models), were conducted using Stata 13. The selection of the most appropriate model was determined based on the results of the Hausman test, ensuring statistical robustness and the minimisation of estimation bias Appendix B.

| AppendixB Escription of Variables and Data Sources | |||

| VariableName | Type | Unit of Measurement | Source (Full Link) |

| Water Availability (Yw) | Dependent Variable | Cubic meters per capita | https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.H2O.INTR.PC |

| AirQuality (Yc) | Dependent Variable | Metric tons per capita | https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.GHG.CO2.PC.CE.AR5 |

| Soil Quality (Yf) | Dependent Variable | Kilograms per hectare | https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.CON.FERT.ZS |

| Female Labour Force Participation (X1) | Independent Variable | Percentage (%) | https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.NE.ZS |

| Female Education (X2) | Independent Variable | Ratio (Female/Male Enrollment Rate) | https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ENR.PRIM.FM.ZS |

| Women’s Representation in Politics (X3) | Independent Variable | Percentage (%) | https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.GEN.PARL.ZS |

| Maternal Mortality Ratio (X4) | Independent Variable | Number per 100,000 live births | https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT |

References

Agarwal, B. (1997). Environmental action, gender equity and women's participation. Development and change, 28(1), 1-44.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Akuthota, S. (2025, July). A Lightweight and Cross-Platform Framework for Real-Time Energy Profiling of Mobile and VR Games. In 2025 International Conference on Computing Technologies & Data Communication (ICCTDC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Azim, S. (2009). Impact of Environmental Degradation on Women. Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Development: Some Perspectives from India, 156-162.

Buckingham, S. (2016). Gender, sustainability and the urban environment. In Fair Shared Cities (pp. 21-32). Routledge.

Gupta, V., Naik, M. N., & Shrivastava, M. M. (2004). Indian women and the environment: vulnerability, efforts, and opportunities. Interdisciplinary Environmental Review, 6(2), 14-36.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hsiao, C. (2022). Analysis of panel data (No. 64). Cambridge university press.

Jayalakshmi, K., & Iyer, S. R. (2018). A study on issues and challenges of women empowerment in India. Editorial Board, 7(11), 73.

Kamla Gupta, K. G., & Yesudian, P. P. (2006). Evidence of women's empowerment in India: a study of socio-spatial disparities.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kumar, K., & Prakash, A. (2019). Examination of sustainability reporting practices in Indian banking sector. Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility, 4(1), 2.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kumari, N., & Shah, S. R. (2024). Examining women's representation in disaster risk reduction strategies across South Asia. Journal ID, 1662, 1547.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mathur, R., Katyal, R., Bhalla, V., Tanwar, L., Mago, P., & Gunwal, I. (2023). Women at the forefront of environmental conservation. Current World Environment, 18(2), 706.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McGinnis, M. D., & Ostrom, E. (2014). Social-ecological system framework: initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecology and society, 19(2).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McManus, P. (2025, January). Introduction to regression models for panel data analysis. Indiana University Workshop in Methods.

Md, A., Gomes, C., Dias, J. M., & Cerdà, A. (2022). Exploring gender and climate change nexus, and empowering women in the south western coastal region of Bangladesh for adaptation and mitigation. Climate, 10(11), 172.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sajja, G. S., & Meesala, M. K. (2024). Analysis on Waste Reduction Strategies for Retailers among their SCM distributional partners. Journal of Modern Technology, 150-174.

Saripudi, K. (2025). A Study on Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing Assistance for Enhancement of Startup Businesses. Journal of Computing and Data Technology, 1(1), 68-76.

Sarkar, R., & Das, G. (2020). Socio-economic development and environmental sustainability: The Indian perspective. Namya Press.

Sharma, L., Poddar, P. N., & Singhal, P. B. (2024). INVESTING IN WOMEN, INVESTING IN THE PLANET: QUANTIFYING THE IMPACT OF WOMEN'S EMPOWERMENT ON ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental, 18(6), 1-16.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Singh, S. (2014). Women, environment and sustainable development: A case study of khul gad micro watershed of kumoun himalaya. Space and Culture, India, 1(3), 53-64.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Soma, A. K. (2025, February). Enhancing Supply Chain Transparency and Integrity: A Permissioned Blockchain Framework. In 2025 International Conference on Emerging Systems and Intelligent Computing (ESIC) (pp. 819-826). IEEE.

Yadav, S. S., & Lal, R. (2018). Vulnerability of women to climate change in arid and semi-arid regions: The case of India and South Asia. Journal of Arid Environments, 149, 4-17.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 04-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16308; Editor assigned: 10-Dec-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-16308(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Dec-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-16308; Revised: 24-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16308(R); Published: 30-Dec-2025