Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 6

Investigating The Role of Websites in Export Marketing in Developing Countries

Ibn Kailan Abdul-Hamid, University of Professional Studies, Accra

Linda Narh, University of Professional Studies, Accra

Andrew Ayiku, University of Professional Studies, Accra

Eunice Yeboah Afeti, University of Ghana

Citation Information: Abdul-Hamid, I.K., Narh, L., Ayiku, A., & Yeboah Afeti, E. (2025). Investigating the role of websites in export marketing in developing countries". Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(6), 1-13.

Abstract

There are several avenues for export marketing, including the use of websites. This study examined how the Ghana Export Promotion Authority (GEPA) utilizes its website to support export marketing in Ghana. A qualitative research approach was employed, with data collected from the GEPA website. The study found that GEPA provides information about export firms in Ghana; however, the information was often either inadequate or inaccurate. Despite this, some efforts by GEPA and the export firms to shape the perceptions of potential clients were evident. The impression management tactics identified included ingratiation, exemplification, and self-promotion. To address these shortcomings, GEPA should consider developing a clear electronic business and marketing strategy to improve the accuracy and completeness of its exporter directory. Doing so could enhance the credibility of GEPA, positively influence prospective clients’ perceptions, and increase website traffic for export-related information. More importantly, non-traditional exporters listed on the GEPA website would be better positioned to improve their export prospects online if GEPA took a more active supervisory role in helping them maintain relevant and up-to-date website content.

Introduction

Websites have become crucial technology for export firms, serving as a gateway for engaging with customers and business partners. Export marketing plays a vital role in the growth and development of national economies (Hinson, 2006; Hinson, Sorensen & Buatsi, 2007), and in today’s digital age, having an online presence is increasingly seen as an essential component of export marketing. Export firms are therefore encouraged to establish and maintain a presence on the internet to boost their export activities and success (Lu & Juliana, 2007; Haluk Koksal, 2008). Numerous researchers have highlighted the business potential of websites and have advocated for their integration into the core activities of export firms (Eshun & Taylor, 2009).

From the perspective of developing countries, studies show that websites can significantly enhance export opportunities (Clarke, 2008; Hinson, 2010). As such, a firm’s website has become an essential marketing channel (cf. Saban & Rau, 2005), offering vital information about the firm and its products, and enabling instantaneous global communication, despite economic, cultural, or commercial differences (Vivekanandan & Rajendran, 2006). Furthermore, it is well established that websites are effective marketing tools that play a key role in the operations of export firms (Hinson, 2005; Law, Qi & Buhalis, 2010). Tesfom and Lutz (2006) argue that firms rely on relevant, accurate, and timely information to better respond to export challenges. In this context, websites serve as valuable platforms for information dissemination, communication, and online transactions for both suppliers and consumers. A considerable body of academic work affirms the positive influence of websites on achieving firm objectives and enhancing export performance (cf. Karavdic & Gregory, 2005; Hinson & Sorensen, 2006; 2007; Lu & Juliana, 2007; Hinson & Adjasi, 2009). The use of websites in export marketing allows firms to bypass traditional export stages, overcome geographical barriers, and quickly establish a global online presence (Gray, McGaughey & Purchell, 2001). This capability removes many organizational and resource constraints typically associated with exporting (Vivekanandan & Rajendran, 2006).

Research on website adoption by export firms has explored why firms choose to adopt technology (Vivekanandan & Rajendran, 2006; Hinson & Boateng, 2007; Sorensen & Hinson, 2009). Common determinants include perceived usefulness, employee IT competency, technology costs, organizational readiness, and top management support (Sorensen & Buatsi, 2002; Hinson & Boateng, 2007). Despite varying adoption factors, the consensus is that websites offer significant benefits to export firms. In Ghana, various aspects of export development have been studied, including strategy formulation, internet adoption, macro-level export analysis, export processing zones, internationalization, and export firm management (cf. Kuada, 2005a, b; Kastener, 2005; Narteh, 2005; Kuada & Thomsen, 2005; Hinson & Sorensen, 2006). Prior research on non-traditional exporters in Ghana has focused on internet use models, perceptions of internet usefulness, and the adoption of internet-based export promotion tools (Hinson, 2001; 2004; 2005a; b). Websites can also shape potential clients’ perceptions of an export firm’s legitimacy, innovation, and customer orientation, though these impressions may vary significantly across firms (Winter, Saunders & Hart, 2003). However, previous studies have not examined the role of export facilitation agencies' websites in promoting export marketing, nor have they explored how these platforms contribute to managing client impressions. This gap provides the basis for the present study, which focuses on the Ghana Export Promotion Authority (GEPA) website.

GEPA is a state agency mandated to support and promote the development of Ghanaian export firms. Its official website (http://www.gepaghana.org) offers information on Ghana’s export activities and directory listings of export firms (Hinson, 2011). Owusu-Frimpong and Mmieh (2007) identified GEPA (formerly the Ghana Export Promotion Council) as the most reliable source of information on Ghanaian export firms. According to Hinson (2011), accurate and relevant information plays a crucial role in enhancing export firm success. Given the strategic importance of digital platforms, this study examines GEPA’s website to assess how it facilitates export marketing in Ghana. Specifically, the study investigates the accuracy and completeness of export firm information provided, as well as the use of impression management (IM) tactics on the platform. This is particularly relevant because potential investors and clients often use GEPA's website to verify whether a firm is legitimate and officially registered with GEPA.

Corporate Websites

Company websites have become increasingly striking and elaborate in their functionality (Campbell & Beck, 2004). Companies have employed website technology for an increasing number of purposes. These have included marketing, selling (Lymer 1999), reporting (Xiao et al. 2002; Marston 2003) and reputation management was cited as a possible function (Campbell & Beck, 2004). A website should clearly reflect the quality efforts made by export firms, because it establishes an important connection with clients (Rocha, 2012). The use of websites by export firms has been reported in extant literature, discussing different facets of the adoption and usage of websites. Corporate websites are used as export marketing channels (Saban & Rau, 2005). Export firm websites provide export firms with functions like publishing; interactivity; transactions; and process improvement (Kosiur, 1997). Some observations of export firm utilization of websites suggest that export firms use lower levels of a website’s functionalities (Korchak & Rodman, 2001; Saban & Rau, 2005). Some attempts at understanding the low levels of utilizing website functionality noted that internet integration, security, privacy and laws and regulations, also limits export firm’s ability to utilize websites at higher levels of functionality (Chaston et al. 2001).

A website evaluation is an important development and operational factor that may lead to the improvement of their users’ satisfaction (Grigoroudis et al., 2008) and to the optimization of invested resources (Rocha, 2012). According to Law et al. (2010), website evaluation is the act of determining a correct and comprehensive set of user requirements, ensuring that a website provides useful content that meets user expectations and sets usability goals. Prior studies on website evaluation fell into two broad categories: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative studies usually generate performance indices or scores to capture the overall quality of a website. For instance, Faba-Perez, GuerreroBote, and de Moya-Anegon (2005) introduced a technique that compares web page measures such as text elements and link formatting. Suh, Lim, Hwang, and Kim (2004) used automated tools to analyze numerically measurable data, such as traffic-based and time-based data, on websites. Likewise, Cox and Dale (2002) built a scoring system with binary classifications for websites of various industries. Hardwick and MacKenzie (2003) applied three different scoring systems to evaluate 19 miscarriage-related websites. Lastly, Yeung and Lu (2004) conducted a longitudinal study of the functional characteristics of commercial websites in Hong Kong based on selected quantitative site attributes and found that the websites were only marginally enhanced after 2.5 years. In qualitative studies, the researchers assess website quality without generating indices or scores. For instance, Heldal, Sjovold, and Heldal (2004) argued that the combination of branding, human–computer interaction, and usability could enhance website evaluation. Liang and Lai (2002) used a consumer-based approach to derive functional requirements for e-store design, and the empirical findings based on three e-bookstores showed that the quality of e-store design had a direct effect on the purchase decision making of students. Kim and Stoel (2004) used the WebQual scale to examine the dimensional hierarchy of apparel websites. The sample comprised female e-consumers, and the empirical results showed that the quality of websites selling apparel products could be conceptualized as a 12-dimension construct.

Impression Management (IM) in Export Marketing

Impression Management (IM) is a recent area of interest within management studies, particularly as it relates to marketing communication. In the context of export firms, IM involves strategic communication efforts aimed at establishing, maintaining, or protecting a desired identity (Rosenfeld, Giacalone, & Riordan, 1995; Bozeman & Kacmar, 1997; Krämer & Winter, 2008). More specifically, IM refers to deliberate actions taken by export firms to influence how they are perceived by both existing and potential customers (Bozeman & Kacmar, 1997; Bolino et al., 2008). IM can be understood as behaviours directed at target audiences to shape and sustain favourable perceptions (Perez, 2009). It is the process through which an export firm attempts to influence the mental image held by external stakeholders (Bolino et al., 2008); Schlenker (1980) defines IM as “the conscious or unconscious attempt to control images that are projected in real or imagined social interactions.” In this light, IM serves as a strategic tool that export firms can consciously manipulate to enhance export success and increase product visibility.

Organizational culture plays a critical role in shaping IM practices. It provides cues and frameworks: such as strategies, policies, symbols, and stories—that communicate and reinforce acceptable behaviours and attitudes (Wexler, 1983; Trice & Beyer, 1984; Leung et al., 2005; Ma et al., 2008). Researchers have identified a range of IM tactics that firms may use to manage external perceptions (Jones & Pittman, 1982; Tedeschi & Melburg, 1984). Jones and Pittman (1982) classify these into five categories:

1. Ingratiation – seeking to be perceived as likable.

2. Exemplification – aiming to be seen as dedicated and morally committed.

3. Intimidation – projecting an image of power or threat.

4. Self-promotion – emphasizing competence and expertise.

5. Supplication – appearing needy or deserving of help.

Of these, ingratiation, self-promotion, and exemplification are associated with positive outcomes for both firms and audiences (Higgins, Judge, & Ferris, 2003). While IM is often linked to the pursuit of specific outcomes, people and organizations may engage in it even when no immediate gain is evident suggesting that deeper psychological or social motivations are also at play (Vries et al., 2009). In today’s digital environment, an export firm’s website serves as a powerful medium for impression management. Website visitors interpret visual and textual symbols through mental models, forming impressions of the firm and making inferences that may influence purchasing behaviours. As such, both web designers and executives should be aware of the website’s role in shaping perceptions and brand identity. Online platforms allow for more strategic control over self-presentation compared to face-to-face interactions. Users can deliberately choose which elements of their identity to showcase and which visual or textual cues to use in crafting their desired image (Ellison, Heino, & Gibbs, 2006; Krämer & Winter, 2008). This capability underscores the importance of Web-based IM as a central component of modern export marketing strategies.

Research Methodology

Export marketing and website utilization studies have employed qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method approaches. Qualitative methods are typically used when the goal is to gain deep insight into export marketing through websites, while quantitative approaches are favored when substantial data is available and lends itself to statistical analysis (Fillis et al., 2004; Hinson & Sorensen, 2006). Given the objectives of this study, (to explore and provide insights rather than generate numerical measurements) a qualitative approach was adopted. This decision was also influenced by the nature of the data collected (Hinson, 2010). This study used archival research to collect data. Archival research involves the analysis of primary sources stored in archives. Jermier and Barley (1998) note that archival materials offer valuable and unobtrusive measures for studying contemporary organizations and are crucial for historical investigations. Archival materials are important because they are widely available, meaningful, and strategically useful. As Zald (1993) suggests, archival research helps define key questions and establish a foundational body of evidence—aligning well with the objectives of this study. The main source of archival data was the website of the Ghana Export Promotion Authority (GEPA), which hosts information on registered export firms in Ghana. In this study, the archival sources were online electronic records.

The population for the study consisted of all registered exporters listed on the GEPA website. A total of sixty-nine (69) companies were listed in the Exporters Directory, accessible via the “Ghanaian Exporters” link on the GEPA homepage. The firms were arranged alphabetically by company name, and each listing contained a set of predefined details: Website; Telephone number.

Mobile number; Fax; Address; Export number; Business information; Data collection occurred in three stages (Data extraction: A data table was created for each company, capturing the predefined details; Verification: All listed companies were contacted via phone calls to confirm the accuracy of the information displayed on the GEPA website. These verification calls lasted no more than two minutes per company; Reporting: A report was compiled for each company detailing the confirmed information. The data collected was later validated and qualitatively analyzed to assess the accuracy and completeness of the website content). The findings were presented in tabular form, including assigned percentages for each information category. To reduce selection bias, only the first company listed under each alphabetical category was selected, resulting in a sample of 15 export firms. These 15 firms served as case studies for analysis and discussion.

Findings and Discussions

The aim of this study was to examine how the Ghana Export Promotion Authority (GEPA) utilizes its website to facilitate export marketing in Ghana. GEPA serves as the National Export Trade Support Institution under the Ministry of Trade and Industry (MOTI), with the mandate to facilitate, develop, and promote Ghanaian exports (http://www.gepaghana.org). Figure 1 presents a snapshot of the GEPA website, illustrating the availability of information on GEPA itself, registered Ghanaian exporters, overseas buyers, and institutional partners.

On the GEPA website, there is a dedicated section for registered Ghanaian exporters. Within this section, a sub-menu provides access to the Exporter Directory, which includes a search field specifically designed to help users find information on Ghanaian exporters. This feature is shown in Figure 2, which displays the Ghanaian Exporter Search Field on the GEPA website.

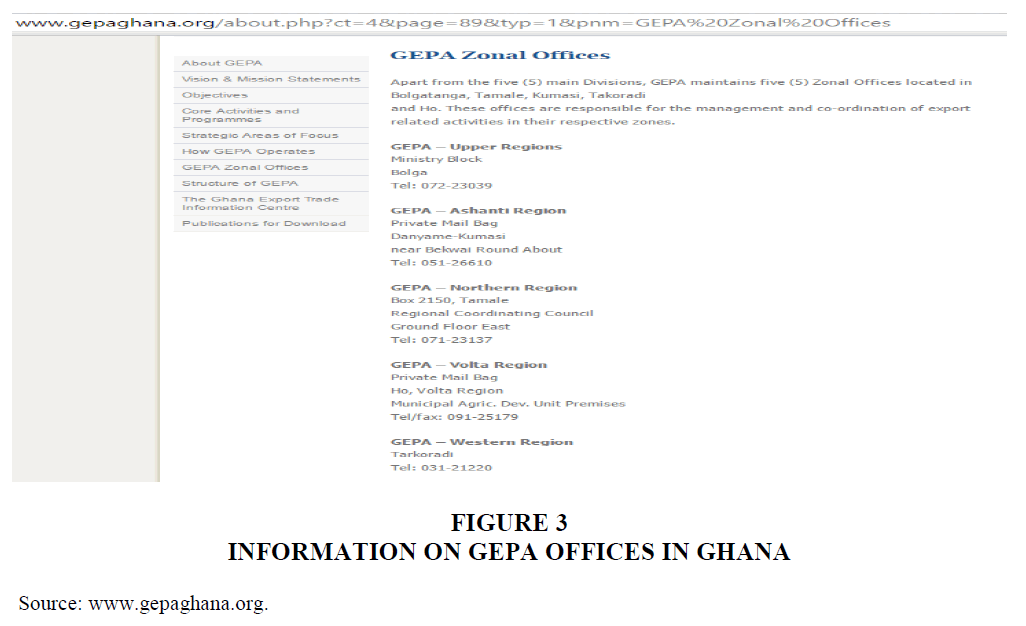

The exporter search field on the GEPA website features a dropdown menu that allows users to browse all registered exporters in Ghana by selecting the first letter (A–Z) of the company’s name. Using this alphabetical search function, a total of sixty-nine (69) export firms were identified. Some of these firms include: African Supply Limited, Be Nice Fashion, Continental Shipping Limited, Darsh Company Limited, Emma-Dov Company Limited, Feanza Industries Limited, Glondosh Company Limited, Home Foods Processing and Cannery Limited, Joecarl Enterprises Limited, Kristara Ghana Limited, Link Dee Company Limited, Nasem Products Limited, Open Way Company Limited, Red Tree Limited, and Waste Recycling Ghana Limited. Several letters—specifically I, M, P, Q, S, T, U, V, X, Y, and Z—had no exporters listed under them. While the search function yielded 69 registered exporters, the GEPA website elsewhere claims that over 3,000 exporting companies are registered. This inconsistency may negatively influence clients' perceptions of GEPA and the reliability of the information it provides. The discrepancy is highlighted by the following statement found on GEPA’s website Figure 3:

“GEPA's clientele include over 3000 registered private sector exporting companies organized into 17 Export Product Associations” – corporate website.

Apart from the national office telephone information, all the listed telephone numbers for GEPA’s zonal offices are inaccurate. The telephone codes 072, 031, and 051 were officially changed in 2010 by the National Communication Authority of Ghana. However, more than five years later, these outdated codes—which are no longer functional—are still displayed on GEPA’s website. As a result, the zonal office telephone numbers are incorrect and inactive. This failure to update and maintain accurate contact information may damage GEPA’s reputation and credibility. Further analysis focused on the specific information GEPA provides for each registered export firm.

The website is intended to offer potential clients the following nine details:

1. Name of the export firm

2. Firm’s website

3. Telephone number

4. Mobile number

5. Fax number

6. Address

7. Registration number

8. Industry of operation

9. Products and services

These nine categories were used to assess the accuracy and completeness of the data for all sixty-nine (69) registered export firms. Each firm's information was examined to evaluate its reliability.

The findings reveal that most of the information provided by GEPA about the export firms is either incomplete or inaccurate. Table 1 presents data on four key categories—1) website, 2) telephone, 3) mobile, and 4) fax numbers. These, along with other firm details, support the conclusion that GEPA’s website provides unreliable information to its users.

| Table 1 Summary of Analysis on all (69) Export Firm Information | |||

| Number | Category | ||

| 1. | Website | Wrong website provided and not functioning but corrected during a call | 1 |

| Unavailable Website | 67 | ||

| Email instead of website | 1 | ||

| 2. | Telephone | Valid | 9 |

| Unavailable | 21 | ||

| Incorrect Number | 33 | ||

| No data available | 1 | ||

| No longer in use by the company | 5 | ||

| 3. | Mobile | Valid | 14 |

| Switched off | 9 | ||

| Unavailable | 16 | ||

| Incorrect number | 14 | ||

| No Answer | 9 | ||

| No data available | 5 | ||

| No longer in use by the company | 2 | ||

| 4. | Fax | Valid | 0 |

| No data available | 8 | ||

| Incorrect number | 61 | ||

Out of the sixty-nine (69) companies listed, sixty-eight (68), representing 98.5%, did not have functioning websites. The only company with a website had an incorrectly spelled domain listed on the GEPA website, rendering it inaccessible. In terms of telephone contact information, thirty-four (34) firms, or 49.3%, had incorrect phone numbers at the time of verification. Fourteen (14) firms were unreachable, and five (5) phone numbers were found to be in use by different subscribers. Only thirteen (13) firms had valid and active telephone numbers. Regarding mobile numbers, only fourteen (14) firms, or 20.2%, had valid mobile contacts. Twenty-five (25) firms (36.2%) had unreachable mobile numbers, and fourteen (14) had incorrect mobile numbers. Nine (9) firms did not answer the calls made during verification, and five (5) had no mobile number listed in the directory. Additionally, two (2) mobile contacts were found to be in use by private individuals not affiliated with the listed firms. For fax numbers, sixty-one (61) firms, or 88.4%, had incorrect fax information. The remaining eight (8) firms had no fax data provided. In terms of physical addresses, only twelve (12) firms had verifiable addresses. The addresses of forty-nine (49) firms could not be confirmed, either because the contact details were invalid or the firms were unreachable. Two firms were found to be no longer in operation, and one firm reported having relocated to a new, unlisted address. Finally, sixty-eight (68) firms had their export registration numbers listed in the directory, while one firm lacked this detail.

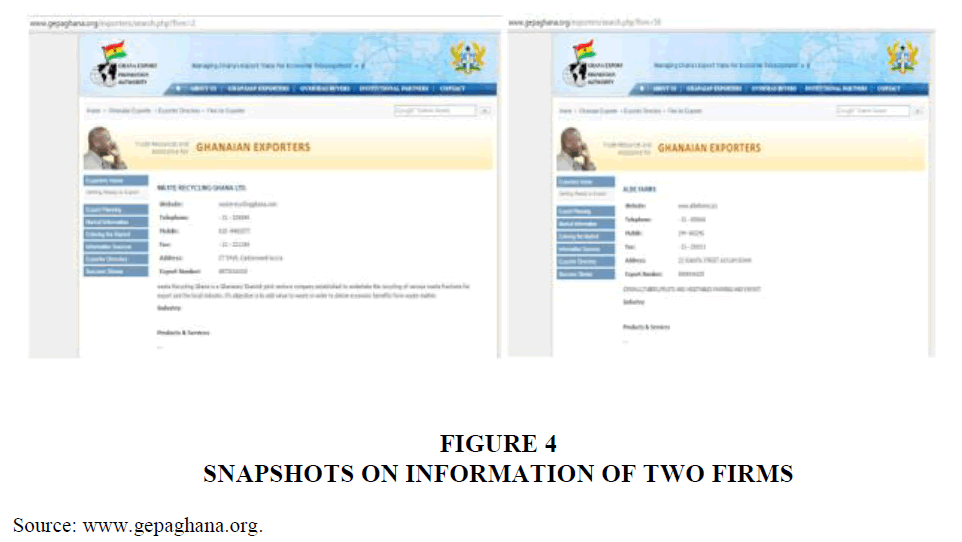

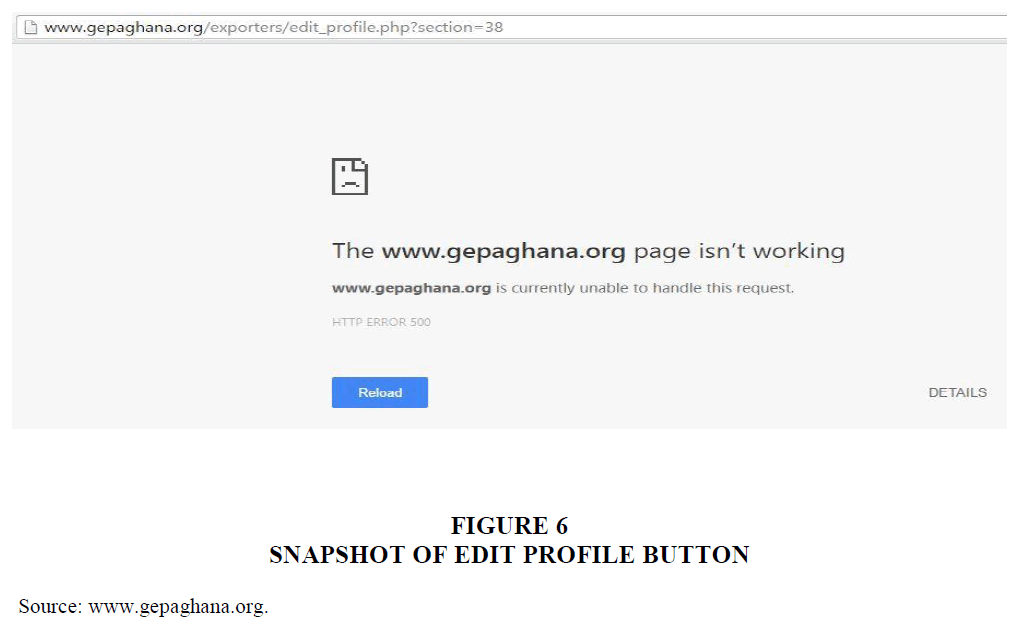

A possible explanation for the failure of Ghanaian exporters to update their information on the GEPA website may be the inactivity of the "Edit Profile" button. Figure 4 below shows the interface that appears after clicking the "Edit Profile" button under the Exporter Directory.

On image creation, maintenance, and protection (IM) of export firms by GEPA. The study found evidence of three out of the five commonly recognized IM tactics—ingratiation, exemplification, and self-promotion—being used by GEPA and the listed export firms. The tactics of intimidation and supplication were not identified. As seen in Table 1, Figure 1, and Figures 4 & 5 (particularly Figure 6), both GEPA and the export firms in Ghana are making efforts toward creating, maintaining, and protecting their corporate image.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The study observed that GEPA is actively promoting exports from Ghana and is attempting to make export-related information accessible to clients and investors through its website (www.gepaghana.org). The adoption of a corporate website is a commendable export marketing strategy and has significant potential to support export promotion efforts in Ghana. While the website includes basic information on 69 registered export firms, much of this information is unreliable or inaccurate. The site appears to lack regular updates and maintenance, as evidenced by numerous errors and outdated details about the listed firms.

Export firms themselves seem largely indifferent to the inaccuracies presented on the site. From the perspective of impression management theory, the GEPA website is falling short in creating, maintaining, and protecting a positive image for both the authority and the firms it represents. Although the GEPA website is likely one of the first points of contact for those seeking information on Ghanaian export activities, this advantage could be lost if users consistently encounter incomplete or incorrect data. A more accurate and up-to-date competitor platform could quickly diminish the website's relevance and credibility.

To maintain its role as a key facilitator of Ghana’s export promotion, GEPA must recognize its website as a critical tool that shapes client and investor perceptions. GEPA should establish a dedicated, competent team responsible for the timely and regular updating of website content. The current management structure—under the Ghana Export Trade Information Centre—has proven ineffective, as demonstrated by the problems identified in this study. Maintaining accurate, reliable information is essential to sustaining user trust. If GEPA continues to provide inadequate or outdated data, clients may seek alternative sources, reducing site traffic and eroding confidence in the organization. Future studies could expand on these findings by including the perspectives of both GEPA staff and the export firms themselves.

References

Bolino, M. C., Kacmar, K. M., Turnley, W. H., & Gilstrap, J. B. (2008). A multi-level review of impression management motives and behaviors. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1080-1109.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bozeman, D. P., & Kacmar, K. M. (1997). A cybernetic model of impression management processes in organizations. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 69(1), 9-30.

Campbell, D., & Cornelia Beck, A. (2004). Answering allegations: The use of the corporate website for restorative ethical and social disclosure. Business Ethics: A European Review, 13(2‐3), 100-116.

Cox, J., & Dale, B. G. (2002). Key quality factors in Web site design and use: an examination. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 19(7), 862-888.

Eshun, E. D., & Taylor, T. (2009). Internet and e-commerce adoption among SME non-traditional exporters: case studies of Ghanaian handicraft exporters.

Gray, S. J., McGaughey, S. L., & Purcell, W. R. (Eds.). (2001). Asia-pacific issues in international business. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Grigoroudis, E., Litos, C., Moustakis, V. A., Politis, Y., & Tsironis, L. (2008). The assessment of user-perceived web quality: Application of a satisfaction benchmarking approach. European Journal of Operational Research, 187(3), 1346-1357.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hardwick, J. C. R., & MacKenzie, F. M. (2003). Information contained in miscarriage-related websites and the predictive value of website scoring systems. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 106(1), 60-63.

Heldal, F., SjøVold, E., & Heldal, A. F. (2004). Success on the Internet—optimizing relationships through the corporate site. International Journal of Information Management, 24(2), 115-129.

Hinson, R. 2001. Exploring the Internet as an Export Promotion tool for SME Non-Traditional Exporters. Unpublished Masters Thesis, University of Ghana Business School.

Hinson, R. (2006). Do Ghanaian non-traditional exporters understand the importance of sales management? Ife Psychologia, 14(1), 26-39.

Hinson, R. (2010). The value chain and e-business in exporting: Case studies from Ghana’s non-traditional export (NTE) sector. Telematics and Informatics, 27(3), 323-340.

Hinson, R. E. (2004). Export and the internet in Ghana: a small and medium enterprise exporter benefit model. LBS Management Review, 9(1), 46-53.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hinson, R. E. (2005). Perceptions of internet usefulness amongst non-traditional exporters in Ghana. Information Technologist (The), 2(1), 40-53.

Hinson, R. E. (2005a). Internet Adoption among Ghana\'s SME Non-Traditional Exporters. Africa insight, 35(1), 20-27.

Hinson, R. E. (2005b). Perceptions of internet usefulness amongst non-traditional exporters in Ghana. Information Technologist (The), 2(1), 40-53.

Hinson, R. E. (2006). Patterns of Internet Use in Ghanaian Business. Journal of Cultural Studies, 7(1), 84.

Hinson, R. E. (2011). Utilising Online and Offline Information in Export: The Case of Firms Operating in Ghana's Non-Traditional Export Sector. Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness, 5(2), 139.

Hinson, R. E., & Adjasi, C. K. (2009). The internet and export: some cross-country evidence from selected African countries. Journal of Internet Commerce, 8(3-4), 309-324.

Hinson, R. E., & Boateng, R. (2007). Perceived benefits and management commitment to e-business usage in selected Ghanaian tourism firms. EJISDC: The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, (31), 5.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hinson, R. E., Sorensen, O., & Buatsi, S. (2007). Internet use patterns amongst internationalizing Ghanaian exporters. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 29.

Hinson, R., & Abor, J. (2005). Internationalizing SME nontraditional exporters and their Internet use idiosyncrasies. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology, 4(2), 229-244.

Hinson, R., & Sorensen, O. (2006). E-business and small Ghanaian exporters: Preliminary micro firm explorations in the light of a digital divide. Online Information Review, 30(2), 116-138.

Hinson, R., & Sorensen, O. J. (2007). E-business triggers: an exploratory study of Ghanaian nontraditional exporters (NTEs). Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations (JECO), 5(4), 55-69.

Hinson, R., Boateng, R., & Jull Sorensen, O. 2008. E-business financing: Preliminary insights from a developing economy context. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 6(3), 196-215.

Jermier, J.M. & Barley, S. (1998). Special Issue of Critical perspectives on organizational control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(2), 235 -510.

Jones, E. E., & Pittman, T. S. (1982). Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. Psychological perspectives on the self, 1, 231-262.

Karavdic, M., & Gregory, G. (2005). Integrating e-commerce into existing export marketing theories: A contingency model. Marketing Theory, 5(1), 75-104.

Kim, S., & Stoel, L. (2004). Apparel retailers: website quality dimensions and satisfaction. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 11(2), 109-117.

Korchak, R., & Rodman, R. (20010. eBusiness adoption among US small manufacturers and the role of manufacturing extension. Economic Development Review, 17(3), 20.

Kosiur, D. R. (1997). Understanding electronic commerce. Microsoft press.

Krämer, N. C., & Winter, S. 2008. Impression management 2.0: The relationship of self-esteem, extraversion, self-efficacy, and self-presentation within social networking sites. Journal of Media Psychology, 20(3), 106-116.

Kuada, J. 2005a. Managing the Internationalisation Processes in Ghana: The Theories and Practices. Internationalization and Enterprise Development in Ghana, Adonis & Abbey Publishers, UK, 10-24.

Kuada, J. 2005b. Internationalisation and enterprise development in Ghana. Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd.

Kuada, J. and Thomsen, G. 2005. Culture, learning and the internationalization of Ghanaian firms, in Kuada, J. (Ed.), Internationalization and Enterprise Development in Ghana, Adonis & Abbey, London, pp. 271-92.

Law, R., Qi, S., & Buhalis, D. 2010. Progress in tourism management: A review of website evaluation in tourism research. Tourism management, 31(3), 297-313.

Leung, K., Bhagat, R. S., Buchan, N. R., Erez, M., & Gibson, C. B. 2005. Culture and international business: Recent advances and their implications for future research. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(4), 357-378.

Liang, T. P., & Lai, H. J. 2002. Effect of store design on consumer purchases: an empirical study of on-line bookstores. Information & Management, 39(6), 431-444.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lu, V. N., & Julian, C. C. (2007). The internet and export marketing performance: the empirical link in export market ventures. Asia pacific Journal of marketing and logistics, 19(2), 127-144.

Ma, S., Hoang, M. A., Samet, J. M., Wang, J., Mei, C., Xu, X., & Stillman, F. A. (2008). Myths and attitudes that sustain smoking in China. Journal of health communication, 13(7), 654-666.

Narteh, B. (2005). Cross-border inter-firm collaboration: Danish-Ghanaian experience, in Kuada, G.J. (Ed.), Internationalization and Enterprise Development in Ghana, Adonis & Abbey, London, pp. 195-216.

Rocha, Á. (2012). Framework for a global quality evaluation of a website. Online Information Review, 36(3), 374-382.

Rosenfeld, P., Giacalone, R. A., & Riordan, C. A. (1995). Impression management in organizations: Theory, measurement, practice. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Saban, K. A., & Rau, S. E. (2005). The functionality of websites as export marketing channels for small and medium enterprises. Electronic Markets,15 (2), 128-135.

Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression management: The self-concept, social identity, and interpersonal relations.

Sorensen, O., & Hinson, R. (2009). E-Business Triggers: Further Insights into Barriers and Facilitators amongst Ghanaian Non-Traditional Exporters (NTEs). Consumer Behavior, Organizational Development, and Electronic Commerce: Emerging Issues for Advancing Modern Socioeconomies, 294-310.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Suh, E., Lim, S., Hwang, H., & Kim, S. (2004). A prediction model for the purchase probability of anonymous customers to support real time web marketing: a case study. Expert Systems with Applications, 27(2), 245-255.

Tedeschi, J. T., & Melburg, V. (1984). Impression management and influence in the organization. Research in the sociology of organizations, 3(31-58).

Tesfom, G., & Lutz, C. (2006). A classification of export marketing problems of small and medium sized manufacturing firms in developing countries. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 1(3), 262-281.

Trice, H. M., & Beyer, J. M. (1984). Studying organizational cultures through rites and ceremonials. Academy of management review, 9(4), 653-669.

Vivekanandan, K., & Rajendran, R. (2006). Export marketing and the World Wide Web: perceptions of export barriers among tirupur knitwear apparel exporters-an empirical analysis. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 7(1), 27.

Wexler, P. 1983. Critical social psychology. Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Winter, S. J., Saunders, C., & Hart, P. (2003). Electronic window dressing: impression management with websites. European Journal of Information Systems, 12(4), 309-322.

Yeung, W. L., & Lu, M. T. (2004). Gaining competitive advantages through a functionality grid for website evaluation. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 44(4), 67-77.

Zald, M.N. (1993). Organization Studies as a Scientific and Humanistic Enterprise: Towards a Reconceptualization of the Foundations of the Field. Organization Science, 4(4), 513-528.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 28-May-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-15975; Editor assigned: 29-May-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-15975(PQ); Reviewed: 10-Jul-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-15975; Revised: 22-Aug-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-15975(R); Published: 03-Sep-2025