Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 1

Kuwaiti Consumers Attitudes towards Adapted Perfume Advertisements: The Influence of Cosmopolitanism, Religiosity, Ethnocentrism and National Identity

Mohamed M. Mostafa, Gulf University for Science and Technology

Fajer S. Al-Mutawa, Gulf University for Science and Technology

Mohaned T. Al-Hamdi, Kansas State University

Abstract

This research examines the influence of cosmopolitanism, religiosity, ethnocentrism, and national identity on Kuwaiti consumers’ attitudes towards adapted versions of advertisements for global perfume brands. The study uses hierarchical regression analysis to formally test the research hypotheses based on a sample of 431 respondents. Results indicate that cosmopolitanism, religiosity, and ethnocentrism have a significant influence on Kuwaiti consumers’ attitudes towards adapted versions of the perfume advertisements for global perfume brands. From a practical perspective, this study highlights the importance of incorporating factors such as cosmopolitanism, religiosity, and ethnocentrism when designing global ads directed to the Middle Eastern consumer. At the theoretical level, the study lends strong support to the adaptation hypothesis in advertising design. At the practical level, the study highlights the importance of understanding cultural sensitivities when designing advertising campaigns geared towards Islamic markets.

Keywords

Consumer Behavior, Advertising Adaptation, Cosmopolitanism, Religiosity, Ethnocentrism.

Introduction

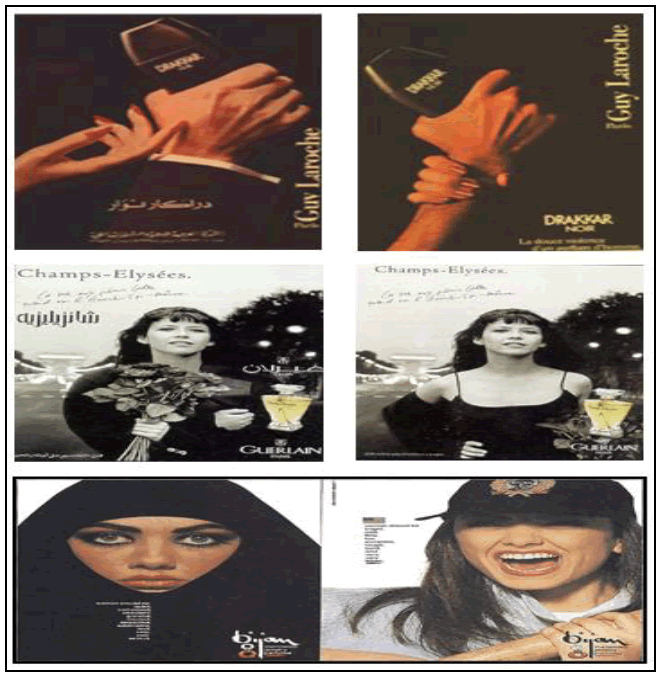

This research examines consumer attitudes towards adapted perfume advertisements in Kuwait. (Please refer to the Appendix for examples of standard vs. adapted versions of advertising campaigns used in Kuwait). Even though the debate on advertising standardization versus adaptation has been the subject of numerous studies, marketing academics still do not have a widely-used decision-making model on which to rely when it comes to advertising adaptation (Krolikowska & Kuenzel, 2008). The question of standardization versus adaptation of advertisements has led to a heated debate among marketing practitioners and academics alike. The conclusion seems to be that there is no clear-cut answer on whether to standardize or adapt a particular advertisement, since this depends on the context, the product/brand, and the targeted consumer. This research contributes to topic by investigating consumer’s attitudes towards adaptation of Western perfume ads in Kuwait, a Muslim country in the Middle East. Evidence suggests that advertising adaptation is most prevalent among perfume advertisements that often employ sexual appeals not co nsidered appropriate for Muslim countries (Seitz & Handojo, 1997).

It has been argued that attitudes towards advertising, in general, influence the success of any advertisement (Mehta & Purvis, 1995). Thus,

“If advertisers know the factors affecting consumers’ behaviors, and the interrelation between these factors and advertising effects, they could further develop their advertising strategies” (Eun & Kim, 2009).

Furthermore, attitude towards the ad affects attitude towards the brand, which impacts purchase decisions (Eun & Kim, 2009).

Attitudes are governed by emotions. Holbrook & Batra (1987) proposed an approach that addresses the intervening effects of emotions in mediating the relationship between advertising content and attitude toward the ad or brand. They found that pleasure, arousal, and domination clearly mediate the effects of ad content (Holbrook & Batra, 1987). Kalliny (2010) found that there are similarities between the Arab world and the US that may allow for minor changes of advertising strategies. Further, Kalliny & Gentry (2007) found that when it comes to ad attitudes, there are some similarities between Arab and American cultures regarding TV advertising content and appeal, contradicting the idea that the two cultures are vastly different. Apart from this research, evaluating consumers’ attitudes towards ad adaptation in the Arab countries has been neglected in terms of international advertising research (Kalliny, 2010).

In a study that focused on culturally normative and product-related ad content, Karande et al. (2006) found that standardization of the cultural norms in advertising to different parts of the Arab world (Egypt, Lebanon, and United Arab Emirates) is appropriate regardless of socio-economic differences, e.g. showing modestly covered women in the ad. However, when it comes to product-related ad content, it is inappropriate to adapt, as socio-economic differences prevail among culturally similar markets (Karande et al., 2006). Similarly, Mostafa (2011) argues that there is a significant difference between Muslims and non-Muslims in Egypt regarding their attitudes towards ethical issues in advertising. The author emphasizes the fact that even within one region, religious orientations impact advertising attitudes. On the other hand, Khairullah & Khairullah (2002) advocate a middle-of-the-road approach in terms of standardization versus adaptation of international advertising. In other words, some degree of standardization is desirable, but product characteristics, consumer characteristics, and environmental factors need to be taken into account to determine the extent of standardization (Khairullah & Khairullah, 2002). However, Ruzevicius & Ruzeviciute (2011) suggest an advertising strategy with compromise based on the optimal combination of standardization and adaptation strategies.

Despite the importance of studying consumers’ attitudes towards ads as a function of cosmopolitanism, religiosity, ethnocentrism, and national identity, no previous studies have investigated the influence of such traits on attitudes towards adapted versions of advertisements in the Arab world, and Kuwait is no exception. This research fills this research gap by examining Kuwaiti consumers’ attitudes towards adapted versions of ads for global perfume brands. Investigating consumers’ attitudes towards adapted versions of global perfume ad campaigns adds depth to the knowledge base about advertising adaptation. By using a theoretically-driven methodology to analyze consumers’ attitudes towards adapted ads, this study also adds breadth to the debate over this relatively new area as perceived by consumers. Finally, by focusing solely on adapted versions, rather than on traditional ad campaigns, this study enriches the knowledge base of this under-represented area. This article proceeds with a review of the literature and hypotheses development. The methodology used to conduct this research follows. We then describe our results and discuss some implications, limitations, and suggestions for further research.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Cosmopolitanism

The concept of cosmopolitanism originates in sociology literature almost 50 years ago (Riefler & Diamantopoulos, 2009). According to Olivas-Lujan et al. (2004), cosmopolitanism is a fine-tuned and sophisticated view of the world, viewing all human beings as belonging to one community. A concept similar to cosmopolitanism is “worldmindedness”, which characterizes those that are

“Increasingly appreciative of world sharing and common welfare and show empathy and understanding towards other societies” (Rawwas et al., 1996).

Another concept that is quite similar to cosmopolitanism is "acculturation". Consumer acculturation is defined as

“The progress that a consumer makes from local consumer culture to global consumer culture with respect to specific cultural components” (Gupta, 2012).

Riefler & Diamantopoulos (2009) argued that consumer cosmopolitanism has gained an increasing attention as a potentially relevant consumer characteristic for explaining foreign product preference and choice. However, empirical evidence of the influence of cosmopolitanism on consumer behaviour research is scarce (Riefler & Diamantopoulos, 2009). Cannon et al. (2002) argued that cosmopolitan consumers tend to be unbiased in the sense that they accept alternative cultural patterns. Acknowledging that cosmopolitan consumers desire to experience culturally diverse products, which enhances attitudes toward global advertising, Lee & Mazodier (2015) tested the effect of cosmopolitanism on the rate of improvement in the brand effect and trust brought about by sponsorship-linked marketing. Using quota sampling and real sponsorship activities during the London Olympics, and applying a Linear Generalized Model (LGM), they found that cosmopolitanism has a positive impact on improvement of brand effect and no change on brand trust. Looking at the effect of cosmopolitanism, Cleveland et al. (2009) verified the hypothesis that cosmopolitanism positively predicts the purchasing frequency of luxury products and globally popular apparel.

Lim & Park (2013) investigated the effects of cosmopolitanism on consumers’ adoption of innovation. The authors conducted a hierarchical model to compare the U.S. and South Korean consumers. They found that the effect of cosmopolitanism on consumer adoption behavior varies across the two countries. The authors showed that cosmopolitanism has a positive effect on the U.S. consumer but a negative impact on Korean consumers’ adoption of innovation. Similarly, Rybina et al. (2010) investigated the effect of cosmopolitanism on purchase behaviour in Kazakhstan. The authors reported a significant negative effect of cosmopolitanism on attitudes of consumers in Kazakhstan toward domestic goods. Abraha et al. (2015) looked at the effect of cosmopolitanism, national identity, and ethnocentrism on Swedish consumers’ purchase behaviour. The authors tested the hypothesis of a negative effect of cosmopolitanism on the purchase of domestic goods, using a sample of respondents from central Sweden, using the same factors used by Rybina et al. (2010). The authors reported a significant negative effect of cosmopolitanism on the purchase of a domestic product.

Unfortunately, there is a paucity of research on cosmopolitanism in the Arab World. A notable exception is Hanley (2008) who conducted an extensive review of the concept of cosmopolitanism in the Arab World. The author argued that the concept has a mental rather than a material dimension in the Arab World. Therefore, the concept plays an active role in political philosophy and cultural studies. Apart from elite secularism, the author did not find any connection of cosmopolitanism to any other social or economic variables in the Arab World. The discussion above suggests the following hypothesis.

H1: There is a negative relationship between cosmopolitanism and attitudes towards the adapted version of the perfume ad.

Religiosity

While the subject of religion has been extensively researched in psychology and sociology, it continues to be an understudied topic in marketing (Essoo & Dibb, 2004). In a similar vein, Moklis (2009) argued that religion received low attention in the literature compared with other cultural aspects. However, religiosity may directly impact attitudes and consumption behavior decisions. Religious beliefs

“Tend to influence the way people live, the choices they make, what they eat and whom they associate with” (Khraim, 2010).

Essoo & Dibb (2004) found that the religious faith of Hindus, Muslims, and Catholics significantly influenced their shopping behavior for TV sets. Further, Clarke (2007) found that the “Christmas spirit” was often given as a reason or excuse for the goodwill, generosity, and altruism associated with the celebration of this Christian festive season. Khraim (2010) provides the first attempt in consumer research to measure religiosity from an Islamic perspective by assessing different dimensions of Islam. The author found that current Islamic issues, religious education, and attitudes towards sensitive products have a substantial influence on consumer behavior.

Some authors have argued that global advertisements that employ sexual appeals in Muslim countries should be adapted (e.g. Al-Makaty et al., 1996; Al-Olayan & Karande, 2000; Rice & Al-Mossawi, 2002). This seems logical as sexual expressions, in general, are regarded as taboos in Islam. Therefore, adapting advertisements to comply with Islamic law will ensure that the ad will not be censored or banned. However, it should be noted that not all Muslims consider themselves religious and not all Muslims practice their faith by following an idealistic version of Islam as stipulated in the Quran. Muslim consumers represent a heterogeneous group. Thus, while sexual appeals in advertising may not appeal to some Muslims, we cannot deny the possibility that sexuality in advertising may appeal to other groups of Muslim consumers. Adaptation may appeal only to those Muslims who strongly identify themselves as religious and diligently practice their faith (Luqmani et al., 1989).

To test the relationship between religious commitment and attitude toward TV advertisements perceived to contain divisive elements, Michell & Al-Mossawi (1995) designed an experiment using two samples of British Christians and Muslims. The authors found that for both groups, religious commitment had a significant role in determining subjects’ attitude toward the TV commercials. Both Christian and Muslim liberals had positive attitudes toward the commercial. However, conservatives from both groups had significant negative attitudes, with Muslim conservatives rating the commercials even more unfavorably than conservative Christians. The authors conclude that the results support the hypothesis of a negative relationship between the degree of religious commitment and the attitude toward TV commercials which include contentious elements.

Fam et al. (2004) investigated the influence of religion on consumers’ attitudes towards advertising of controversial products. Using data from six countries and categorizing religious groups into four main categories, the authors report statistically significant differences between the religious groups. Using a factor grouping approach of controversial products instead of looking at a few or single items, the authors examined the extent of religious beliefs (Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, and non-religious believers) on the offensiveness of those products. The authors report that all four religious groups view political advertising as offensive, and Muslims and Buddhists also found addictive products as offensive as well. Muslims were offended more than the other groups by political advertisements. In addition, Muslims found advertisements for health and care products and gender-related products more offensive than the other religious groups. Looking at the intensity of religious belief, the authors found that the religiously devout were more likely to view advertisement on gender products, health and care products, and addictive products offensive than the less devout followers. Particularly, devout Muslims found the advertisement of these products and political advertisements very offensive compared to their more liberal followers.

To examine the effect of religiosity on Muslim consumer behavior and purchasing decisions, Alam et al. (2011) used a survey of middle and upper-income groups in the Selangor state of Malaysia. The authors tested the hypothesis that religiosity mediates the relationship between independent factors and consumers’ buying behavior. The authors found that religiosity acts as a mediating effect on the relationship between relative and contextual variables influencing Muslim consumers’ buying behavior. The discussion above suggests the following hypothesis.

H2: There is a positive relationship between religiosity and attitudes towards the adapted version of the perfume ad.

Ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism is a sociological concept that is used regularly by marketers (Saffu & Walker, 2005). Saffu & Walker (2005) argued that ethnocentrism focuses on the belief that one’s in-group is superior to others. Consumer ethnocentrism can be found in both advanced and developing countries (Saffu & Walker, 2005). The CETSCALE, a 17 item Likert scale, has been recognized as the most suitable quantitative method to measure ethnocentrism (Saffu & Walker, 2005). The CETSCALE was developed and formulated by Shimp & Sharma (1987) to measure consumer ethnocentrism. The authors define ethnocentrism as the set of beliefs held by consumers about the appropriateness and morality of purchasing foreign-made products instead of locally made ones. The strength, intensity, and magnitude of consumer ethnocentrism vary from one country to another. Consumer ethnocentrism proposes that nationalistic emotions affect attitudes about products and purchase intentions. Particularly, it implies that purchasing imported products is wrong because it is unpatriotic and harmful to the national economy (Kaynak & Kara, 2002). Cleveland et al. (2009) tested the hypothesis that ethnocentrism positively predicts behaviours associated with traditional foods and fashion, and negatively affects behaviors associated with globally popular foods and apparel, importance of owning consumer electronics, and the frequency of behaviours associated with modern media. The authors reported that products associated with these behaviours would be poor candidates for foreign brand penetration into areas where strong sentiments of ethnocentrism are held. The authors found support for the negative behaviour of consumers with high ethnocentrism toward globally popular brands.

Rybina et al. (2010) tested the hypothesis that ethnocentric attitudes of consumers have a negative effect on foreign purchase behaviour in Kazakhstan. The authors' results supported the negative effect of ethnocentrism on buying foreign products and the positive effect on buying domestic products. Similarly, Abraha et al. (2015) tested the effect of ethnocentrism on Swedish consumers’ purchase behaviours. Specifically they tested the positive effect of ethnocentrism on domestic purchase behavior and the negative effect on foreign purchase behavior. The authors found no support for the negative effect of consumer ethnocentrism. However, they found that ethnocentrism better explains consumers’ positive attitudes toward purchasing domestic products vis-à-vis foreign goods. In essence, consumers did not dislike foreign products but they merely purchased domestic ones to ease the normative influence of their conscience.

Vadhanavisala (2014) tested the hypothesis that ethnocentrism has an influence on Thai consumers’ intentions to purchase domestic products. Using a questionnaire to gather the data and, and based on the CETSCALE to assess the consumers’ beliefs about their ethnocentrism, the author reported a significant positive relationship between ethnocentrism and the intention to purchase domestic goods. In other words, consumers’ ethnocentrism positively influences their intention to purchase domestic goods. Similarly, Nadiri & Turner (2010) investigated the influence of ethnocentrism on consumers’ intentions to buy domestic products in North Cyprus. They tested the hypothesis that consumers’ ethnocentrism is positively related to their intentions to purchase domestically produced goods. Again using a questionnaire and the CETSCALE, the authors report that the results showed a significant positive relationship between ethnocentrism and intention to purchase domestic goods, as expected.

Ziemnowicz & Bahhowth (2008) explored the effect of ethnocentrism on consumer habits in the Middle East. Using results from exploratory surveys of consumers in Lebanon and Kuwait. Results showed that the Lebanese consumers prefer to purchase local products and view imports as a negative factor that hurts the economy and contributes to unemployment in Lebanon. The authors report that Kuwaiti consumers also like to support their local products, even if it will cost them more. The authors argued that, in general, Kuwaiti consumers are not against foreign products, however, they prefer local ones. Furthermore, Kaynak & Kara (2002) studied the effect of ethnocentrism on Turkish consumers’ behavior. The authors used a market segmentation approach to understand the country-of-origin perception that existed among Turkish consumers. The authors reported that Turkish consumers had a very positive perception about products imported from Japan, the USA, and Western European countries. These products are perceived to have a well-known brand name, to be technologically advanced, to be luxurious, to have good style and appearance, and to be heavily advertised. On the other hand, Russian, Chinese, and Eastern European products are perceived to be inferior in terms of durability, reliability, and service. Therefore, Turkish consumers did not have positive perceptions about the products imported from these countries.

National Identity

Another notion similar to ethnocentrism is nationalism or national identity. Nationalism characterizes supreme consumer loyalty towards the “local” which, in turn, has significant effects on consumer attitudes and purchase intentions (Rawwas et al., 1996). Consumers that consider themselves to be “nationalists” prefer local brands and products, as they believe that imported goods may damage their economy. Keillor & Hult (1999) implemented the national identity construct across different cultures. The authors also aimed to establish general national identity norms to use in cross cultural comparisons. Using a sample from five countries, they found that national identity can make a difference in behavioural decisions.

In a study about the effect of national identity on multinational promotional strategies in Europe, Dunn (1976) found that change in advertising strategy was greater in developed markets than in developing markets and that such local autonomy represented a disenchantment with the notion of standardization of ads. Looking at the effect of national identity on the strategies of international marketers in Asia, Phau & Chan (2003) used the National Identity Framework (NATID) developed by Keillor and Hult to study the influence of national identity across four Asian countries. The authors found that consumers in Thailand and Singapore have the strongest and weakest national identity, respectively. The authors emphasized the importance of national identity and suggested that the sense of national identity is not influenced by level of national development. They pointed out that a relatively weak sense of national identity and ethnocentric tendency can help international marketers to launch new products. The authors also found that the product will have a higher chance of success and the investment cost and risk can be reduced. They also found that similarities and differences in national heritage, cultural homogeneity, belief system, or consumer ethnocentrism will work as an indication of how much standardization or customization has to be done for the target country.

Jory (1999) discussed the growth of national identity in Thailand. He acknowledged that the Thai cultural identity moved more into commercial medium. Big corporations and state enterprises produce advertisements that play on the theme of Thai culture. Previously, the state used the discourse of Thai identity to win the hearts and minds of Thai citizens for the purpose of identifying national interest. However, national identity strategies are used more as a commercial strategy to win the loyalty of Thai consumers. Focusing on the conceptual strengths and empirical limitation of NATID, Chi Cui & Adams (2002) assessed the relevance of the national identity construct in Yemen. Using a sample of 208 Yemeni citizens. The authors indicated that the core elements of national identity conceptualized in the NATID scale are transient to a large degree, and the first-order and higher-order factor of national identity are attainable. The discussion above suggests the following hypothesis.

H4: There is a positive relationship between national identity and attitudes towards the adapted version of the perfume ad.

Methodology

Sample and Measures

Mall intercepts were selected by randomizing the day of the week and hours of the day to recruit respondents. While the mall intercepts method is not perfect, this survey approach can result in

“A sample, which, while not strictly representative, may nonetheless be relatively free of any systematic bias” (Douglas & Craig, 1983).

Seven hundred and fifty questionnaires were distributed. Each questionnaire included a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study and its implications relative to ad adaptation attitudes. For the purpose of maintaining confidentiality and anonymity, names of respondents were not required. In total, 431 people responded, generating an effective usable response rate of 57%. This response rate is typical in social science research (Sekaran & Bougie, 2003). A chi-squared test revealed no significant difference between early and late respondents. There was a balanced split between males (54%) and females (46%) in the sample. Mean age was 37.3, with a standard deviation of 17.8.

Procedures

All measures used in this study were taken from Cleveland et al. (2009) study. However, since the scales had not previously been validated in an Arab non-Western context, the calculation of item-total correlations for the pooled data was first used as a basis for detecting poor items. Items with item-total correlation of 0.35 or less were eliminated from the analysis. Following recommendations by Anderson & Gerbing (1988), the retained items were subjected to an exploratory principal component analysis, separately for each scale, to further investigate the unidimensionality of the scales. We chose the oblique rotation, since the survey dimensions are expected to be correlated. Advocates of the oblique rotation assert that, in the real world, important factors are likely to be correlated; thus searching for unrelated factors is unrealistic (Dixon, 1993). Finally, the retained items were combined into sum scales and reliabilities and means were calculated. The reliabilities, measured with Cronbach’s alpha, ranged from 0.657 to 0.949. Cronbach’s alpha is considered, for the most part, to be a conservative estimate of a construct’s reliability (Carmines & Zeller, 1979).

Results

Product-Moment Correlations

Though it does not prove causation, correlation can serve as a predictor of causation (Sekaran, 2000). The product moment correlations between the variables give a feel for the association among the model’s five constructs Table 1. Most of the correlation coefficients were significant and had the expected sign. Thus, the constructs, in general, are highly related. However, this result should be interpreted with some caution due to the large sample size.

| Table 1 Product-Moment Correlation Matrix | ||||

| ATT | COS | REL | SET | |

| COS | 0.163** | 1 | ||

| REL | 0.198** | -0.097 | 1 359 |

|

| CET | 0.198** | 0.152** | 0.145** | 1 |

| NAT | 0.196** | 0.091 | 0.456** | 0.188** |

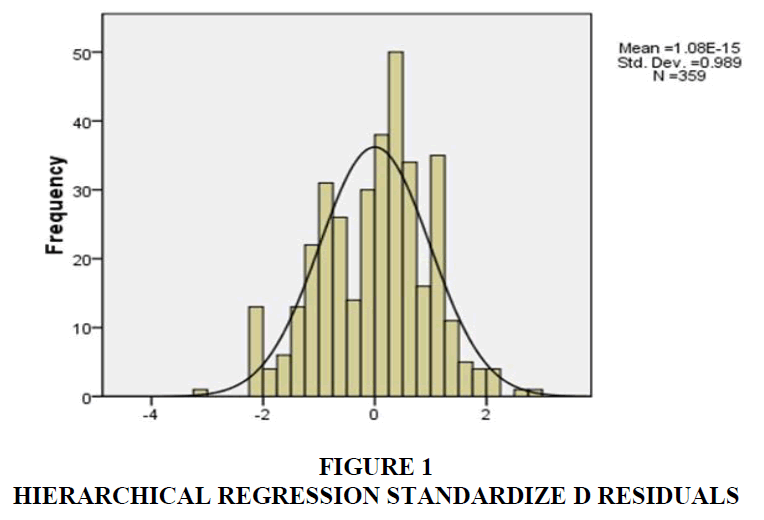

Hierarchical Regression Analysis

Hierarchical regression analysis, or incremental variance partitioning (Pedhauzur, 1982). It was used to formally test the research hypotheses. This approach allowed us to focus on the variables forming the hypotheses, while simultaneously sieving out the influence of the control variables that might have a moderating effect on consumer attitudes towards ad adaptation. This method can also be used to control the order of the variables entered into the regression model, allowing us to assess the incremental predictive ability of any variable of interest (McQuarrie & Langmeyer, 1985). Diagnostic checks conducted Figure 1 show that hierarchical regression assumptions were not violated.

Table 2 shows the results of the hierarchical regression analysis. Following Geldern et al (2008), age, marital status, and educational level were used as control variables in the first step of the regression. These control variables explained just 3% of consumer attitudes as indicated by the R-squared in model 1. In the second step, the cosmopolitanism variable was entered because previous research found a positive relationship between attitude and cosmopolitanism (e.g. Gupta, 2012). The inclusion of this variable increased the explanatory power of the model to 7.2%, a change of about4% in the R-squared. This change was significant at the 0.01 level, as shown in Table 2. In the third step, the religiosity variable was entered in the hierarchical regression analysis. This variable was entered based on previous research reporting a positive relationship between religiosity and consumer attitudes towards advertising (e.g. Essoo & Dibb 2004; Clarke, 2007; Khraim, 2010 etc). The inclusion of this variable increased the explanatory power of the model to 10%, a change of around 3% in the R-squared. This change was found to be significant at the 0.01 level, as shown in Table 2.

| Table 2 Hierarchical Regression | |||||||

| Model | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | R Square | R Square Change | Sig. F Change | Durbin-Watson |

| Beta | |||||||

| 1) (Constant) Gender AGE MAR EDU |

-0.137 -0.002 0.132 -0.012 |

17.645 -2.551 -0.028 2.301 -0.223 |

0.000 0.011 0.977 0.022 0.824 |

0.032 | 2.929 | 0.021 | |

| 1) (Constant) Gender AGE MAR EDU COS |

-0.134 -0.037 0.197 -0.008 0.209 |

8.493 -2.538 -.626 3.353 -.152 3.917 |

0.000 0.012 0.531 0.001 0.879 0.000 |

0.072 | 0.040 | 0.000 | |

| 1) (Constant) Gender AGE MAR EDU COS REL |

-0.094 -0.067 0.177 0.014 0.224 0.184 |

5.403 -1.763 -1.131 3.058 0.265 4.248 3.484 |

0.000 0.79 0.259 0.002 0.791 0.000 0.001 |

0.103 | 0.031 | 0.001 | |

| 1) (Constant) Gender AGE MAR EDU COS REL CET |

-0.100 -0.066 0.168 -0.003 0.198 0.161 0.141 |

4.546 -1.900 -1.118 2.920 -0.048 3.725 3.024 2.727 |

0.000 0.058 0.264 0.004 0.962 0.000 0.003 0.007 |

0.122 | 0.019 | 0.007 | |

| 1) (Constant) Gender AGE MAR EDU COS REL CET NAT |

-0.092 -0.73 0.168 -0.002 0.189 0.127 0.133 0.079 |

3.899 -1.744 -1.232 2.918 -0.038 3.513 2.178 2.555 1.369 |

0.000 0.082 0.219 0.004 0.969 0.000 0.030 0.011 0.172 |

0.127 | 0.005 | 0.072 | 1.491 |

b. Predictors: (Constant), EDU, MAR,GENDERAGE,COS

c. Predictors: (Constant), EDU, MAR,GENDERAGE,COS,REL

d. Predictors: (Constant), EDU, MAR,GENDERAGE,COS,REL,CET

e. Predictors: (Constant), EDU, MAR,GENDERAGE,COS,REL,CET,NAT

f. Dependent Variable: ATT

In the fourth step, the ethnocentrism variable was entered. This variable was also significant at the 0.01 level and explained an additional 2% of the variance. In the last step the national identity variable was entered into the model. It explained virtually nothing, and the change in R-squared was almost zero. Taken together, our results confirm the positive influence of religiosity and ethnocentrism on attitudes towards advertising adaptation. However, our results do not support that national identity or cosmopolitanism influence consumers’ attitudes towards adapted advertising in Kuwait.

Conclusion

Implications, Limitations and Future Research

In collectivist cultures where social values play a major role, such as Kuwait, customization may be preferred in advertising that uses explicit sex appeal. Previous research such as Karande et al. (2006) found that standardization of the cultural norms in advertising to different parts of the Arab world (Egypt, Lebanon and United Arab Emirates) is appropriate regardless of socio-economic differences, e.g. showing modestly covered women in the ad. However, when it comes to product-related ad content, it is inappropriate to standardize as socio-economic differences prevail among culturally similar markets (Karande et al., 2006). Similarly, Mostafa (2011) argues that there is a significant difference between Muslims and non-Muslims in Egypt regarding their attitudes towards ethical issues in advertising. Although Kuwaiti consumers are all Muslim, individuals differ in terms of religiosity. Younger generations are more open to accepting global appeals in advertising (Al‐Mutawa, 2013). This research supports Khairullah & Khairullah’s (2002) and Ruzevicius & Ruzeviciute’s (2011) approach in adapting international advertising. However, because this study used a survey approach, the findings cannot be generalized beyond the sample surveyed. As quantitative studies rely on statistics rather than consumer insights, there is a limitation as to how far the data may be generalized.

Marketing research in emerging markets, such as Kuwait, is generally lacking, because most consumer research focuses on Western societies and consumers. It would be useful to conduct a mixed method study using surveys as well as interviews or focus groups. The different methods will allow for triangulation of the data. In future research, it would be interesting to know how consumers would respond to ambiguous appeals in advertising. This study aims to encourage further marketing research in developing markets, as those markets continue to be exposed to western media and advertising. Insights will be useful for both theory and practitioners.

Appendix: Standardized vs. adapted advertising campaigns

References

- Abraha, D., Radón, A., Sundström, M., & Reardon, J. (2015). The Effect of Cosmopolitanism, National Identity, and Ethnocentrism on Swedish Purchase Behavior. Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 18(February), 1-12.

- Alam, S.S., Mohd, R., & Hisham, B. (2011). Is Religiosity an Important Determinant on Muslim Consumer Behavior in Malaysia? Journal of Islamic Marketing, 2(1), 83-96.

- Al-Makaty, S.S., Van Tubergen, G.N., Whitlow, S.S., & Boyd, D.A. (1996). Attitudes Toward Advertising in Islam. Journal of Advertising Research, 36(3), 16-26.

- Al‐Mutawa, F.S. (2013). Consumer-Generated Representations: Muslim Women Recreating Western Luxury Fashion Brand Meaning through Consumption. Psychology and Marketing, 30(3), 236-246.

- Al-Olayan, F.S., & Karande, K. (2000). A Content Analysis of Magazine Advertisements from the United States and the Arab World. Journal of Advertising, 29(3), 69-82.

- Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411-423.

- Cannon, H.M., Sasser, S., & Yaprak, A. (2002). Incorporating Cosmopolitan-Related-Focus-Group Research into Global Advertising Simulations. Development in Business Simulation and Experimental Learning, 29, 9-20.

- Carmines, E.G., & Zeller, R.A. (1979). Reliability and Validity Assessment. Sage Publications, London.

- Chi Cui, C., & Adams, E.I. (2002). National Identity and NATID: An Assessment in Yemen. International Marketing Review, 19(6), 637-662.

- Clarke, P. (2007). A Measure for Christmas Spirit. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(1), 8- 17.

- Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., & Papadopoulos, N. (2009). Cosmopolitanism, consumer ethnocentrism, and materialism: An eight-country study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of International Marketing, 17(1), 116-146.

- Dixon, P.M. (1993). The Bootstrap and the Jackknife: Describing the Precision of Ecological Indices. In: Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments. Ed. Scheiner, S. & Gurevitch, J. New York: Chapman and Hall.

- Douglas, S.P., & Craig, C.S. (1983). Examining Performance of U.S. Multinationals in Foreign Markets. Journal of International Business Studies, 14(3) (winter), 51-62.

- Dunn, S.W. (1976). Effect of National Identity on Multinational Promotional Strategy in Europe. Journal of Marketing, 40(4), (October), 50-57.

- Essoo, N., & Dibb, S. (2004). Religious Influences on Shopping Behavior: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(7/8), 683-712.

- Eun, H.Y., & Kim, H.S. (2009). An Affectability Consumer’s Attitudes Toward Advertising Based Interactive Installation in Public Transportation: Changing Outdoor Advertisement on Street by Interactive Bus Shelter. Proceedings of the International Association of Societies of Design Research, Coex, Seoul, Korea. 99- 112.

- Fam, K.S., Waller, D.S., & Erdogan, B.Z. (2004). The Influence of Religion on Attitudes Towards the Advertising of Controversial Products. European Journal of Marketing, 38(5/6), 537-555.

- Geldern, M.V., Brand, M., Praag, M.V., Bodewes, W., Poutsma, E., & Gils, A.V. (2008). Explaining Entrepreneurial Intentions by Means of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Career Development International, 13(6), 538-559.

- Gupta, N. (2012). The Impact of Globalization on Consumer Acculturation: A Study of Urban, Educated, Middle Class Indian Consumers. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 24(1), 41-58.

- Hanley, W. (2008). Grieving Cosmopolitanism in Middle East Studies. History Compass, 6(5), 1346-1367.

- Holbrook, M.B., & Batra, R. (1987). Assessing the Role of Emotions as Mediators of Consumer Responses to Advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 404-420.

- Jory, P. (1999). Thai Identity, Globalization and Advertising Culture. Asian Studies Review, 23(4), 461-487.

- Kalliny, M. (2010). Are They Really that Different from Us: A Comparison of Arab and American Newspaper Advertising? Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 32(1), 95-108.

- Kalliny, M., & Gentry, L. (2007). Cultural Values Reflected in Arab and American Television Advertising. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 29(1), 15-32.

- Karande, K., Almurshidee, K.A., & Al-Olayan, F. (2006). Advertising Standardization in Culturally Similar Markets: Can We Standardize All Components? International Journal of Advertising, 25(4), 489-512.

- Kaynak, E., & Kara, A. (2002). Consumer Perceptions of Foreign Products: An Analysis of Product Country Images and Ethnocentrism. European Journal of Marketing, 36(7/8), 928-949.

- Keillor, B.D., & Hult, G.T.M. (1999). A Five Country Study of National Identify: Implications for International Marketing Research and Practice. International Marketing Review, 6(1), 65-82.

- Khairullah, D.H., & Khairullah, Z.Y. (2002). Dominant Cultural Values: Content Analysis of the U.S. and Indian Print Advertisements. Journal of Global Marketing, 16(1/2), 47-70.

- Khraim, H. (2010). Measuring Religiosity in Consumer Research from Islamic Perspective. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 2(2), 166-179.

- Krolikowska, E., & Kuenzel, S. (2008). Models of Advertising Standardization and Adaptation: It’s Time to Move the Debate Forward. The Marketing Review, 8(4), 383-394.

- Lee, R., & Mazodier, M. (2015). The Roles of Consumer Ethnocentrism, Animosity, and Cosmopolitanism in Sponsorship Effects. European Journal of Marketing, 49(5/6), 919-942.

- Lim, H., & Park, J.S. (2013). The Effects of National Culture and Cosmopolitanism on Consumers’ Adoption of Innovation: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 25(1), 16-28.

- Luqmani, M., Yavas, U., & Quraeshi. Z. (1989). Advertising in Saudi Arabia: Context and Regulation. International Marketing Review. 6(1), 59-72.

- McQuarrie, E.F., & Langmeyer, D. (1985). Using Values to Measure Attitudes Toward Discontinuous Innovations. Psychology and Marketing, 2(winter), 239-252.

- Mehta, A., & Purvis, S. (1995). When Attitudes Towards Advertising in General Influence Advertising Success. Paper Presented at the 1995, Conference of the American Academy of Advertising, Norfolk, VA.

- Moklis, S. (2009). Relevancy and Measurement of Religiosity in Consumer-Behavior Research. International Business Research, 2(3), 75-84.

- Mostafa, M.M. (2011). An Investigation of Egyptian Consumers’ Attitudes Towards Ethical Issues in Advertising. Journal of Promotion Management, 17, 42- 60.

- Nadiri, H., & Tumer. M. (2010). Influence of Ethnocentrism on Consumers’ Intention to Buy Domestically Produced Goods: An Empirical Study in North Cyprus. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 11(3), 444-461.

- Pedhauzur, E.J. (1982) Multiple Regression in Behavioral Research (2nded.). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Phau, I., & Chan, K.W. (2003). Targeting East Asian Markets: A Comparative Study on National Identity. Journal for Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 12(2), 157-172.

- Rawwas, M.Y., Rajendran, K.N., & Wuehrer, G.A. (1996). The Influence of World Mindedness and Nationalism on Consumer Evaluation of Domestic and Foreign Products. International Marketing Review, 13(2), 20-38.

- Rice, G., & Al-Mossawi, M. (2002). The Implications of Islam for Advertising Messages: The Middle Eastern Context. Journal of Euromarketing, 11(3), 71-96.

- Riefler, P., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2009). Consumer Cosmopolitanism: Review and Replication of the CYMYC Scale. Journal of Business Research, 62(4), 407-419.

- Ruzevicius, J & Ruzeviciute, R. (2011). Standardization and Adaptation in International Advertising: The Concept and Case Study of Cultural and Regulatory Peculiarities in Lithuania. Current Issues of Business and Law, 6(2), 286-301.

- Rybina, L., Reardon, J., & Humphrey, J. (2010). Patriotism, Cosmopolitanism, Consumer Ethnocentrism and Purchase Behavior in Kazakhstan. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 1(2), 92-107.

- Saffu, K., & Walker, J.H. (2005). An Assessment of the Consumer Ethnocentric Scale (CETSCALE) in an Advanced and Transitional Country: The Case of Canada and Russia. International Journal of Management, 22(4), 556-571.

- Seitz, V.A., & Handojo, D. (1997). Market Similarity and Advertising Standardization: A Study of the UK, Germany and the USA. Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science, 3(3), 171-183.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2003). Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach. John Willey and Sons, New York.

- Shimp, T.A., & Sharma, S. (1987). Consumer Ethnocentrism: Construction and Validation of the CETSCALE. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(3), 280-289.

- Vadhanavisala, O. (2014). Ethnocentrism and its Influence on Intention to Purchase Domestic Products: A Study on Thai Consumers in the Central Business District of Bangkok. A Journal of Management, 12(2), 20-30.

- Ziemnowicz, C., & Bahhowth, V. (2008). Relevance of Ethnocentrism Among Consumers In Kuwait. Unpublished manuscript. http://www.sedsi.org/2008_Conference/proc/proc/p071010031.pdf. Downloaded 10/26/2015.