Review Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 4

Labour Security and Urban Informal Women Workers: An Investigation of Selected Urban Areas of West Bengal, India

Ashish Kumar Biswas, Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, Hyderabad

Chandrima Chatterjee, Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, Hyderabad

Citation Information: Biswas, A.K. & Chatterjee, C. (2023). Labour security and urban informal women workers: an investigation of selected urban areas of west bengal, india. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal,27(4), 1-10.

Abstract

This work is with respect to labour security of women workers in urban informal sector in West Bengal, India. We use the word “labour security” and “social security” in this work interchangeably, although they do not exactly mean the same things. While social security is a much broader concept which applies to all the people irrespective of whether they are in the labour force of the country at a time or not, labour security is defined as providing certain benefits (other than wage payments) to a labourer as his/her right or entitlement(s). However, the present study examines whether women workers in urban informal sector enjoy any labour security or not. A primary survey has been carried out in selected districts of West Bengal, India and a labour-security index is calculated based on the variables captured through primary survey. Status of labour security between men and women in informal sector is also captured in this study. Finally, the paper renders some useful policy recommendations in order to improve the condition of informal workers, especially women workers.

Keywords

Informal Sector, Labour, Security, Women, India.

Introduction

Women play a crucial role in the development of human society. Approximately one-third of households in the developing country like India are female-headed where women are responsible for the needs of their families. This has led to an increasing emphasis on women’s involvement in informal economic activities. The informal sector is the primary source of employment for women in most developing countries. The proportion of women workers in the informal sector exceeds that of men in most countries. UN data shows that female informal workforce contributes significantly to GDP. According to the Census of India 2001, women constitute 48.2 percent of the total population and the women workers constitute 25.68 percent of the total workforce in the country. Despite having made significant contribution to their families, women informal workers are subject to severe discrimination in terms of wages, types of employment and other social issues. In general, a woman worker who is working outside her family/household bears the double burden of (a) performing domestic chores and (b) working outside her family to earn some income to supplement the total family income.

Social security is another very important issue in case of informal employment because by definition informal employment is the kind of employment which is without any security of employment as well as social benefits that are generally enjoyed by formal sector workers – men and women Anker & Annycke (2010). We can think of social security scheme especially for women informal workers in terms of women empowerment, voice representation, financial security and many others. Despite there being several acts and regulation in favour of women workers, low skilled women workers face severe discrimination in their work places they mostly do not have choice of work and lack bargaining power. Although, specific government policies are there in favour of women informal workers, in practice these labour legislations are rarely complied. Moreover, the women workers are mostly unaware of the existence of these laws Chen (2001).

Objective of the Study

The basic objectives of the study are the following:

1. To examine the levels of labour security of women in the selected urban areas of West Bengal.

2. To compare the levels of labour security of urban informal women workers with the levels of labour security of urban informal male workers.

Informal Sector and Women Workers

Since the inception of LPG regime employment in the informal sector has increased rapidly in all regions of the world. Most of the developing economies have experienced a decline in formal wage employment and a concomitant rise in informal employment Dutt (1999).

According to Swaminathan (1991), the term, ‘informal sector’ usually refers to either enterprises or employment or both of them; the two may overlap but do not always coincide. Informal employment may signify employment in informal sector as well as employment in formal sector as non-regular worker. The absence of registration in the case of an informal enterprise implies the absence of labour legislation. So, workers in an informal enterprise do not enjoy any labour rights so to say. The term informal enterprise may be defined as comprising of establishments whose existence or status is not regulated. Here, regulation of the status of an enterprise refers to licensing, i.e. obtaining a permit from the authority of registration. With this definition, the informal sector comprises of all unregistered and unlicensed enterprises Eapen (2001). The National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector (NCEUS) while taking note of these aspects decided to complement the definition of informal sector workers as those workers working in the informal sector or households, excluding regular workers with social security benefits provided by the employers and the workers in the formal sector without any employment and social security benefit provided by the employers. So Employment in the informal sector has been defined as comprising of self-employed workers, home-based workers, informal factory workers, unpaid family workers and hired casual/contractual/daily labourers and casual/contractual (non-regular or non-permanent) workers in formal sector (Swaminathan 1991). Sen and Dasgupta (2009) identified one noticeable fact of recent time which is the growing informalization of the formal space in terms of replacement of regular or permanent workers by casual and contractual workers who hardly enjoy any benefit generally given to a permanent worker.

However, in case of women, they enter the labour market in the informal sector mostly as wage earners but occupy secondary position in the workforce vis-à-vis their male counterpart. Their significance remains generally devalued (Dhar & Dasgupta 2014). An earlier study made by Unni (1998) pointed out that female workers (particularly in the informal sector in rural/urban areas) are compelled to spend at least half a day in their income-generating works excluding the fact that they also are to perform their domestic chores in most male-headed families as is the general norm of patriarchy. However, their economic activities always remained devalued when they are compared with their male counterparts in the similar kinds of activities in both formal and informal sectors. When it comes to the employment of a woman in the urban areas it is mostly in the urban informal economic activities and there too certain informal economic activities are envisaged as the best suited for women only (as if feminity and the nature of some jobs in urban informal economy meant for women go hand in hand). So, there remains the problem of stereotype. And from this angle also a woman engaged in some urban informal economic activity in India is often more vulnerable than a man in the same activity as a typical unskilled and illiterate/less-educated women are not aware of their rights as contributors’ to the country’s economic wealth (measured in terms of GDP) and do lack the strength or willingness for collective bargaining or their voice representation out of some fear psychosis given the nature of uncertainty they encounter in their daily life (both at home and at the labour market) vis-à-vis their male counterparts (both in the family and at the workplaces), which we have observed during our field survey for the present work in last one and half year in the nine districts of West Bengal Jhabvala & Subramanya (2000). In the urban informal economy of India, as the official data (mainly NSSO data) suggests, there is growing significance of this (informal) sector in urban areas and this growing significance is much more pronounced after the inception of the LPG regime (Liberalization, Privatisation and Globalization.). And unskilled as well as illiterate/low-educated women belonging to the low-income group and/or BPL (or even just above the APL) families are more and more forced to enter the urban informal labour market in various forms. Women in the urban informal economy are mainly engaged as own-account workers which include home-based workers and self-employed and sub-contracted labourers in various kinds of economic activities mainly to supplement their own low family incomes for the minimum bare social survival for their own family members including themselves.

Social Protection and Labour Security for Urban Informal Women Workers

Labour security, as a concept, is different from the concept of social security or even economic security which we have already indicated. While social/economic security as defined by the ILO and as is understood in mainstream economics today is a concept based on, as per our own understanding, on either the principal-agent problem framework where state as the principal incurs the agency cost in terms of specific social security expenses for the targeted groups of population (the agents) out of its (liberal) political democracy obligations to secure vote banks or as the typical client-patron relationship where state as patron is the benefactor in providing benefits to the targeted beneficiaries (the clients). Subrahmanya (2000) pointed out that social security measures are of two types - promotional and protective. Promotional measures consist mainly of employment, training and nutrition schemes by which a person is able to work and can earn income. On the other hand, protective measures consist of schemes by which the state provides the means of livelihood when a person is not able to work Sen & Dasgupta (2009). Unorganized informal sector workers are generally not covered by these social security provisions or even if they are covered they are not aware of these schemes as our field survey experience in West Bengal suggests.

It is worth mentioning that there are some specially designed programmes for women workers or women working poor especially in the informal sector. Two of them are discussed below:

Support to Training and Employment Programme for Women (STEP):

The objective of this scheme is to upgrade the skills of poor and asset-less women by providing training, some financial assistance so as to ensure a secured employment on a sustainable basis in the traditional sectors like agriculture, dairy, handlooms and handicrafts and like.

This is a financial scheme for working poor women in the informal sector mainly. In 1993, a fund was created by the Union Government with the avowed objective of economically empowering working poor women in the informal sector in order to meet their credit needs of them for some economically productive activities generally. Credits up to Rs. 2,500 as short term loan and Rs. 5,000 as medium term loan are decided to be given to each borrower (women who are economically poor) through some selected NGOs (Subrahmanya 2000).

Our idea of labour security, on the other hand, is based on the neoliberal vision of an economic agent who must be (in normative sense) capable and efficient enough to protect his/her present as well as future economic life while contributing to the national wealth (measured in terms of GDP or GNP) of the country Unni (2002). The question that remains how far for an individual economic in this present LPG regime is possible to garner this security on his/her own and whether the state or outside assistance is still very much wanted to supplement a part of his/her effort for securing his/her present and future (economic) life. Following Sen and Dasgupta (2009) our concept of labour security is based upon the following components:

(1) Income security

(2) Work Security

(3) Job Security

(4) Skill Reproduction Security

(5) Voice Representation Security

(6) Financial Security

(7) Social Security

An urban woman informal worker – particularly if she is forced or stressed to participate in the labour market as a supplier of her labour power – is in majority working poor (NCEUS 2006). Hence, the question of labour security for her is of utmost importance given the fact in most of the cases in urban poor and/or low-income families they supplement their family income by working outside (while performing also the domestic chores) not out of their own choice (rather involuntarily) and remains always vulnerable relatively more than men when she encounters any sudden crisis in her own family (economic and/or non-economic crisis both at the micro as well as macro level). However, in our concept of labour security social security is also a component and, hence social security benefits as they are defined in mainstream economics are subsets of our concept of labour security which is an individual rational economic agent oriented concept when we compare it with the given notion of social/economic security.

Data and Methodology

A field survey was conducted in selected districts of West Bengal to gather primary information from the urban informal men and women workers. Not only the women informal workers are surveyed, but also the male informal workers are also surveyed in order to get a comparative view of labour security of urban informal women workers.

Women workers along with male workers are engaged in several urban informal activities such as tailoring, beedi making, construction work, weaving, self employed small and unorganized business, domestic household (paid) services, hired daily labouring activities (mostly unskilled) of various types as we have found from our field surveys. As far as labour security of urban informal women workers are concerned, we wanted to measure it in terms of an index number which we have termed here Informal Workers’ Labour Security Index ( IWLSI henceforth).These workers were interviewed to understand the following aspects of their occupation and social life :

• Wages ( daily/ weekly/ monthly/piece rate or otherwise)

• Whether receiving any retirement benefits like provident fund, gratuity etc.

• Financial conditions of the worker in terms of having bank accounts, other assets like own house, vehicles, gold etc.

• Income earned (regular or seasonal)

• Whether unionized or not

For collection of information semi-structured interview method was adopted. These workers were contacted at their work place such as construction sites, tailor shop, household employing maid servants, different slums of the major areas etc.

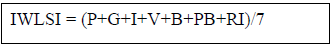

To estimate the degree of social security measures available to informal workers, a particular index, and ‘The Informal Worker’s Labour Security Index was constructed on the basis of data collected from the interview. The method of constructing the index is described below:

First of all from the primary database collected from selected districts of West Bengal, seven parameters are taken into consideration for the purpose of constructing the index namely

1. Income (I)

2. Provident Fund (P)

3. Gratuity (G)

4. Voice representation (V)

5. Presence of bank account (B)

6. Purpose of bank account (PB)

7. Nature of income (RI)

Rationale behind taking these parameters as indicators of labour security of informal workers are the following:

1. Income is important determinant of social protection. Income below ‘minimum wage’ and/or irregular income threatens socially necessary minimum subsistence of an individual.

2. Provident fund and gratuity are the non-wage retirement benefits related to the organized sector workers. We are taking them into account here because of the fact, of late; the government of India has passed an Act for the unorganized sector workers in 2008 where provision of provident fund for some categories of unorganized sector workers is there.

3. Given present policies regarding financial inclusion, presence of bank account and involvement in banking activities seem to be very important determinant of informal workers’ labour security. This parameter determines whether the informal worker is financially included or not.

4. Ability to raise voice against social injustice and deprivation strongly determines worker’s labour security measure. We have tried to capture this in terms of whether an informal worker is unionized or not.

Variables are coded in binary set up- if yes , the variable is coded as 1 , otherwise the variable is coded as 0.

• P : If there is provident fund then P=1, otherwise P=0

• G : If there is gratuity then G=1, otherwise G=0

• I : If income is above the minimum wage then I=1, otherwise I=0

• V : If there is Union membership then V=1, otherwise V=0

• B : If there is bank account then B=1, otherwise B=0

• PB : If there is saving then PB=1, otherwise PB=0

• RI : If there is regular income then RI=1, otherwise RI=0

Now we are in a position to define the Informal Workers’ Labour Security Index ( IWLSI)

where P stands for provident fund, G stands for gratuity, I stands for income level, V stands for voice representation, B stands for bank account, PB stands for savings and RI stands for regular income.

Each component is coded with the value either 0 or 1. The index is constructed by taking simple average of these parameters, and hence, it is expected that the value of the index should vary between 0 and 1. The values close to 1 will indicate high levels of security and the values close to 0 will indicate lower level of security.

The primary survey was conducted in nine districts of West Bengal – (1) Kolkata, (2) Maldah, (3) Howrah, (4) Hooghly, (5) North 24 Paraganas, (6) Nadia, (7) Murshidabad, (8) Burdwan and (9) West Midnapore. We have already mentioned that these districts were chosen purposively as per our own convenience of time, cost and easy accessibility of places.

Eight types of informal workers were interviewed as follows:

(1) Business Owners: Self-employed persons having small shops and/or home based production (business) activity.

(2) Domestic Care givers: Workers engaged for domestic household activities on regular and/or temporary basis.

(3) Weavers: Workers engaged in weaving clothes, baskets and carpets in their home. Most of the workers under this category work as informal counterpart of any formal weaving industry as subcontracted labour and/or they independently supply the finished goods to the market.

(4) Casual labourers: Workers in subcontracted productive activities, seasonal hired workers for various types of unskilled manual activities like cleaning, decoration for a particular function/festival and like.

(5) Tailors: Either employed in any tailoring shop as hired workers and/or as self-employed working at home or at outside home.

(6) Beedi-binders: Mostly engaged in beedi-binding activities at home and very much prone to occupational health problems.

(7) Construction labourers: Mostly hired workers from rural areas and some are engaged in these activities seasonally, not permanently in urban areas.

(8) Daily labourers: Non-regular workers employed in various small factories as casual/temporary/contractual workers and hired workers for unskilled manual jobs (sometime even little skilled jobs) on daily wage basis.

On the basis of the data collected above, three types of IWLSI indices were calculated:

• Gender–wise IWLSI

• District–wise IWLSI

• Type of work–wise IWLSI

The grading of the IWLSIs is as follows:

1. 0.75 – 1.00 : very high

2. 0.50 - 0.75 : just above average

3. 0.25 - 0.50 : critical

4. 0.00 - 0.25 : worst

Results and Discussion

Table 1 and 2 shows both district-wise and gender-wise labour security measure available for informal workers. For all the districts, the IWLSI scores are higher for female workers compared to that of the male workers. The IWLSI is higher for districts like Kolkata, Maldaha, Howrah, Hooghly for both female and male workers. The worst situation prevails in West – Midnapore IWLSI score is at its critical level. However, for districts like Nadia, Murshidabad and Burdawan, the IWLSI score is at its critical level for male informal workers where as for female informal workers the same is just above the average.

| Table 1 Gender Details |

|

|---|---|

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Gender | IWLSI |

| Male (N=610) | 0.500821 |

| Female (N=590) | 0.592978 |

| Table 2 District-Wise Iwlsi |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| District | Sample Size (N) | IWLSI | Sample Size (N) | IWLSI |

| Kolkata | 27 | 0.58 | 42 | 0.58 |

| Maldah | 33 | 0.52 | 33 | 0.67 |

| Howrah | 03 | 0.52 | 46 | 0.64 |

| Hooghly | 05 | 0.51 | 70 | 0.63 |

| North-24 Parganas | 133 | 0.50 | 139 | 0.68 |

| Nadia | 298 | 0.50 | 221 | 0.51 |

| Murshidabad | 75 | 0.46 | 21 | 0.57 |

| Burdwan | 14 | 0.45 | 08 | 0.50 |

| West Midnapore | 20 | 0.40 | 09 | 0.44 |

Table 3 shows work-wise IWLSI score both for male and female urban informal workers. For male workers, IWLSI score is highest for business owner category and for female workers it is highest for maid servant category. The maximum labour security is enjoyed by female domestic care givers. Urban female informal workers with type of work as business owner, tailor, construction labour and daily labour have IWLSI score just above average but female workers with type of work weaver, casual labour and biri binder are at critical level. On the other hand, male worker with type of work as tailor, biri binder, construction labour, daily labour and casual labour have IWLSI score at the critical level. Male worker with type of work as business, domestic care givers, weaver have IWLSI score just above the average.

| Table 3 Work-Wise Iwlsi |

||

|---|---|---|

| Type of work | IWSI Male | IWSI Female |

| Business | 0.64 | 0.63 |

| Domestic Care givers | 0.57 | 0.67 |

| Weaver | 0.51 | 0.47 |

| Casual labour | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| Tailor | 0.48 | 0.53 |

| Biri binder | 0.43 | 0.47 |

| Construction labour | 0.43 | 0.59 |

| Daily labour | 0.40 | 0.59 |

The condition for casual labour and biri binder is at critical level for both male and female. So workers attached with these two types of work need much attention.

Conclusion

Our study brings a surprising result that instead of having severe gender discrimination in informal sector in terms of wage differentials, workload, work status, working hours, training etc., the informal workers Labour security index (IWLSI) is slightly higher for women workers compared to men workers. This is due to the fact perhaps that in recent years some new employment security and economic security schemes have been implemented for women workers in informal sector. Among them, Support to Training and Employment Programme for Women (STEP), schemes of Welfare Fund, Rastriya Mahila Kosh are worth mentioning. Moreover the services of some voluntary organizations is worth mentioning in this respect.

But actually the value of the labour security index is low both for men and women informal workers, which reveals the fact that the level and status of labour security enjoyed by the urban (men and women) informal workers is not sufficient. The conditions of biri-binder, casual labour, weaver are vulnerable. Biri-binders are more prone to occupational health hazards. Casual labour, weavers do suffer from some insecurity. IWSI score is also very for Kolkata which requires a separate investigation.

It is worth mentioning that labour security conceptually differs from social security. Our study is limited in the sense that some important components of urban informal worker’s labour security could not be taken into account in our work like age, education, marital status and like. While carrying out our field survey in the selected urban areas of nine districts of West Bengal, we have observed that almost all the informal workers (irrespective of their sex, age and education) are hardly aware of the different social security benefits that they are entitled to from the union government and also from the government of West Bengal. So , we think that it is the responsibility of the state as well as different civic bodies and civil society organizations (including labour unions) to make the urban (men and women) informal workers aware of these social security benefits.

In conclusion, on the backdrop of our present research the following policy imperatives may be recommended:

1. To make informal workers aware of present social benefit scheme

2. To make the informal as well as formal enterprises responsible to give proper identity to the informal workers attached to them so that these workers can enjoy the existing social security benefits

3. Urban informal workers are much less organized in order to represent their collective voice unlike the permanent workers in the informal sector of the Indian economy. Hence, we do feel that the Indian state should take necessary steps legally and otherwise so as to enable the urban informal workers (especially those who are working poor) to make their voices freely represented to the concerned authority which is already included as one of the basic Fundamental Rights of the Constitution of India for all the citizens of India irrespective of their gender, caste, religion and social status (especially either as economically rich or economically poor).

References

Anker, R., & Annycke, P. (2010). Reporting regularly on decent work in the world: Options for the ILO. ILO.

Chen, M. A. (2001). Women and informality: A global picture, the global movement. Sais Review, 21(1), 71-82.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dhar, A., & Dasgupta, B. (2014). When Our Lips Speak “Genderlabour” Together?. Development on Trial–Shrinking Space for the Periphery, 307-407.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dutt, R. (1999). Food Security in India, Paper prepared for the Seminar on Social Security in India, organized by the Institute of Human Development and Indian Society of Labour Economics. New Delhi, April, 15-17.

Eapen, M. (2001). Women in informal sector in Kerala: need for re-examination. Economic and Political Weekly, 2390-2392.

Government of India. (2007). Report on conditions of work and promotion of livelihoods in the unorganised sector. National Commission for Entreprises in the Unorganised Sector.

Jhabvala, R., & Subramanya, R.K.A. (Eds.). (2000). The unorganised sector: Work security and social protection. SAGE Publications Pvt. Limited.

Sen, S., & Dasgupta, B. (2009). Unfreedom and waged work: Labour in India's manufacturing industry. SAGE Publications India.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Swaminathan, M. (1991). Understanding the''Informal Sector''A Survey.

Unni, J. (1998). Women in Informal Sector: Size and Contribution to Gross Domestic Product. MARGIN-NEW DELHI-, 30, 73-94.

Unni, J. (2002). Size, contribution and characteristics of informal employment in India. Gujarat Institute for Development Research, Ahmedabad, India.

Received: 22-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13188; Editor assigned: 24-Jun-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-13188(PQ); Reviewed: 08-Jul-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-13188; Revised: 20-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13188(R); Published: 27-Jul-2023