Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 6

Linking Organizational Culture and Employer Brand Perceptions through Multiple Mediators

Soumendu Biswas, Management Development Institute, Sukhrali, Gurgaon Haryana

Citation Information: Biswas, S. (2025). Linking organizational culture and employer brand perceptions through multiple mediators". Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(5), 1-15.

Abstract

This study investigates the linkage between employees’ perceptions of their organizational culture and their employer’s brand when mediated by their psychological contract and organizational identification as the first- and employee engagement as the second-order mediators, respectively. For this purpose, relevant theories were explored and the literature was reviewed to postulate the study hypotheses which were subsequently assimilated as a conceptual latent variable model. The study constructs were operationalized with standard measures and 603 usable data were collected from managerial employees in India. Thereafter, different statistical techniques including path and mediation analyses as per structural equation modeling procedures were applied. Based on these procedures, the measurement model, all the study hypotheses, and the proposed latent variable model were empirically confirmed. The study concludes by noting its theoretical and practical implications, its limitations, and future research scopes arising thereof.

Keywords

Employees’ perceptions of organizational culture, Psychological contract, Organizational identification, Employee engagement, Employees’ perceptions of employer brand, Structural equation model.

Introduction

The generally accepted organizational practices to remain relevant in their respective business are market penetration, market development, and market dominance. However, this is mainly about changes in an organization’s external environment, concerning its external stakeholders, and its sustenance in an external context. While such detailed and sophisticated market research may prepare an organization to meet these external challenges, it needs concerted efforts to minimize internal friction and maximize effective decision-making. For this purpose, an organization should have an attractive image in the minds of its employees that strengthens their intentions to stay and contribute gainfully to the organization’s objectives.

In this connection, an employer brand has been defined as, among others, ‘…psychological benefits provided by employment and identified with the employing organization’ (Ambler & Barrow, 1996, p.187). Ergo, employees’ shared assumptions and the congruity of their perceptions about such desirable notions about their organization’s core message that leads to their identification with their employing organization have been defined as the organization’s culture. However, a clear association between employees’ common perceptions of their organization’s culture and their notions of the psychological benefits that describe their employer’s brand has been hard to come by and its investigation was, therefore, considered a primary purpose of this study.

Moreover, of the various intervening variables that connect an organization’s culture and its brand value as an employer among its employees, a primary requirement would be the strength of their contractual association and employees’ organization-based identity which keep them engaged with their job and, by extension, the organization. A paucity of studies synthesizing these constructs was also recognized as a research gap and has been addressed in this study.

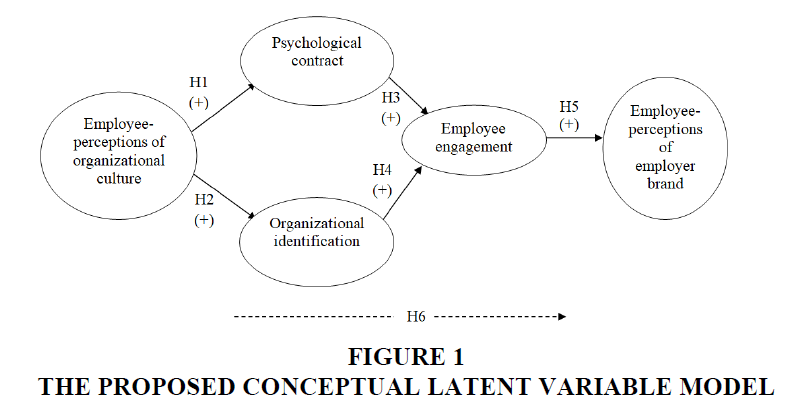

Accordingly, this study intends to conceptually develop and empirically test a latent variable model (LVM) that demonstrates the linkages between employees’ perceptions of organizational culture (EPOC) and employees’ perceptions of the employer brand (EPEB) vis-à-vis the organization whose members they are. Additionally, it proposes to look into the viability of potential mediators such as psychological contract, organizational identification, and employee engagement while connecting EPOC and EPEB.

Theoretical Background

While employees of an organization are expected to have an overall agreement about their organization’s strategic plans concerning its contingent exigencies, organizations on their part need to attract and retain a workforce with the broader organizational objectives of long-term competitive sustainability (Bednar et al., 2020). This conveys that if EPOC is based on information dissemination and participation in strategic ideation, it promotes a deep involvement of organizational members. In this regard, an employer and its employees connect through some form of a contractthat is both, transactional and relational and which, in turn, is guided by the culture of the organization as perceived by its stakeholders. Accordingly, it may be reasonably assumed that the strength of an employee’s psychological contract with his/her employing organization shall be a directly influences by EPOC where, from the perspective of the social exchange theory (SET), employees’ conceptions of an acceptable psychological contract may be viewed as the actualization of the reciprocity norms in return for EPOC that strengthens their organizational fitment (Leicht-Deobald et al., 2021).

Extant literature describes culture as a common denominator of social values and norms that are shared by members who occupy a common space and with some common goals with their organization. Specifically, organizational culture refers to the “shared basic assumptions that a group learns as it solves its problems of internal integration and external adaptation” (Schein, 1983). As per the shared reality theory, there is nothing right or wrong or good or bad about an organization’s culture as it is just a matter of the strength of collated perceptions. As such, irrespective of the taxonomy of culture an organization may typify, for instance, achievement culture, bureaucratic culture, or role culture (Cameron & Quinn, 2011), at the collective level these create a social identity regarding the organization in the minds of a majority of its employees. This deliberation denotes the social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel & Turner, 2004) as the basis for the association between EPOC and EPEB through employees’ organizational identification.

A culture that includes employee voice in its strategy formulation and decision-making indicates an organization’s employee-directed value propositions that create a favourable EPEB. This connection between EPOC and EPEB is captured by the signal theory where an organization sends signals about its culture which helps employees create a favourable image of it. Coupled with the strength of employees’ psychological contract with their employing organization and their identification with the same, the relevant literature implies that employees who are more engaged with their job and the organization will have greater clarity about their employer’s brand equity.

The following section reviews the literature to establish the relationships among the constructs as rooted in the theories discussed above.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

EPOC, Psychological Contract, and Organizational Identification

As a contextual construct, the culture of an organization epitomizes the norms and mores that are practiced and adhered to by its employees and are valued by its stakeholders (Lee et al., 2018). Implicit in this statement is an element of complimentary anticipation where an organization and its members tend to bind each other through a mutually fulfilling reciprocal relationship that may not be solely pecuniary. Thus, viewed as a covenant, EPOC may be considered as an instrument that motivates its current employees to stay and appreciate their psychological contract with their employing organization (Soomro & Shah, 2019).

In this connection, the difficulty of matching the plurality of an individual’s identity in terms of his/her response consistency against culture cues signaled by their organization can be offset by a convergence of shared organizational reality and their own identity (Kuroda et al., 2022). It is this confluence of identities that helps in employees’ organizational identification, more so, when he/she perceives a commonality of organizational practices, policies, values, and assumptions among other stakeholders as EPOC (Binu Raj, 2021). In other words, EPOC gives an organization’s members their unique identity thus triggering in them a sense of organizational identification (Erkutlu & Chafra, 2016).

Based on the discussion above, the following study hypotheses are postulated.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Employees’ perceptions of organizational culture have a positive connection with employees’ psychological contracts.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Employees’ perceptions of organizational culture can be linked positively to employees’ organizational identification.

Psychological Contract, Organizational Identification, and Employee Engagement

To continue, a psychological contract is based on the services an individual offers to an employer in return for the opportunities and benefits he/she receives (Pattnaik & Sahoo, 2021). Derived from this notion of contract fulfillment, both parties make a subjective evaluation of whether the benefits outweigh the costs of continuing the relationship, and if the results of such assessments are affirmative, they dynamically engage in organization-specific activities (Behery et al., 2016).

Since work is a salient aspect of an individual’s life, the clearer one is about its purpose, the more persistent he/she becomes regarding its fulfillment (Demirtas et al., 2017). The literature indicates that employees who perceive their work to be meaningful can match their professional selves with their organization’s context (Vough, 2007). Such employees may feel intrinsically motivated to be engaged with his/her role-related tasks in particular and that of the organization in general (Biscotti et al., 2018). As such, employees may be expected to be more engaged when there is a sense of concomitant personal significance in and identification with the work they do and the organization for whom such work is done (Rodwell et al., 2022).

Furthermore, when employees realize self-concordance between their work and the workplace, they simultaneously discern symmetry between their personal and organizational goals and aspirations (Nazir & Islam, 2017). This results in their augmented sense of job and organizational attachment, prosocial behaviour, and internalization of organizational tenets (Giessner, 2011). Moreover, when individuals identify themselves with their organization, there is a sense of predictability and reduced uncertainty since organizational actions are perceived as what one him/herself would do under the circumstance. Accordingly, the incorporation of organizational tenets and precepts as per EPOC leads to a merger of their selves with a broader entity namely, their organization, giving them a heightened sense of psychological safety and affective affinity and this magnifies their levels of job and organization-directed engagement (Swaroop & Sharma, 2022). The preceding discussion leads to the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Employees’ psychological contract has a positive association with employee engagement.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Employees’ organizational identification is positively associated with employee engagement.

Employee Engagement and EPEB

As per the discussion so far, employee engagement can be regarded as a consequence of a set of favourable estimations that individual members make about their organization’s culture and its consequent impact on their psychological contract fulfillment and organizational identification (Karjaluoto & Paakkonen, 2019). Accordingly, employees voluntarily act as employer brand advocates for their organization and contribute to the formation of their organization’s brand equity (Boukis et al., 2017). Moreover, studies indicate that higher levels of employee engagement not only increase employees’ job and organizational involvement but also deepen their psychological propinquity toward their employing organization leading to more favourable EPEB (Spoljaric & Vercic, 2022). Accordingly, the following study hypotheses may be posited.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Employee engagement shares a positive link with employees’ perceptions of the employer brand.

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Psychological contract and organizational identification shall operate as first-order mediators and employee engagement shall function as a second-order mediator between employees’ perceptions of organizational culture and employees’ perceptions of the employer brand.

Overall, the study hypotheses are compiled as a conceptual LVM in Figure 1 below and proffered for further empirical scrutiny.

Method

Sample and Procedures

Data for this study were collected through a random survey conducted in multiple organizations spread across India. With an a prioi moderate effect size of .30, the desired statistical power level of .80, the number of latent variables as 31 and observed variables as 22, and a probability level of .05, the minimum sample size required to detect effect was 250 and the recommended sample size was 806. Accordingly, a sample size between 250 and 806 was judged acceptable for this study.

A step-by-step approach was adopted to collect data for this study. First, the Yellow Pages business directory was used to randomly select 30 organizations in India. Next, the Human Resources (HR) departments of these 30 organizations were approached to seek permission for data collection. 13 out of these 30 organizations agreed to allow their employees to participate in the survey that followed. Of these 13, eight organizations were from the services sector and carried out businesses related to life and general insurance, banking, advertisement and HR consultancy, financial services, and hotels and tourism. The remaining five were from the manufacturing sector and included organizations involved in construction, automobile manufacture, iron and steel manufacturing, and refractories and tin plating. Subsequently, a list of respondents who voluntarily agreed to fill up the study questionnaire was prepared. A cover letter explaining the purpose of the study, a short profile of the researcher, and a pledge of anonymity of respondents along with a written assurance that the data being collected would serve no commercial purpose accompanied each questionnaire. Of the 850 questionnaires that were floated, 603 filled-up and usable questionnaires were returned. Thus, the response rate for this study was about 70.94 percent.

The average age of the respondents was 37.24 years with an average work experience of 11.02 years. Of the 603 respondents, 47.76 percent belonged to the junior, 40.59 percent to the middle, and 11.65 percent to the senior levels of management of their respective organizations. Further, about 65 percent of the total respondents belonged to manufacturing whereas about 35 percent of the respondents belonged to services sector organizations. Also, 63.69 percent of the respondents were males and the remaining 36.31 percent were females.

Measures

All the study constructs were operationalized and measured on a five-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

EPOC. EPOC was measured by adapting eight items of the Organizational Culture Profile (OCP) scale developed and reported by O’Reilly et al. (1991). The OCP captures eight factors of organizational culture as perceived by its employees such as innovation, attention to detail, outcome orientation, aggressiveness, supportiveness, emphasis on rewards, team orientation, and decisiveness. An example item from the inventory was, ‘This organization takes risks, is innovative, and is open to experimenting with different ways of doing things’. The reliability index for this measure was .82.

Psychological contract. Psychological contract was measured by the 18-item psychological contract scale developed and reported by Raja et al. (2004). As per the measure, psychological contract comprised two subfactors namely, transactional contract and relational contract comprising nine items each. Sample items from transactional and relational contract inventories were ‘I work only the hours set out in my contract and no more’ and ‘I expect to grow in this organization’, respectively. Two items of the transactional contract measures were reverse-scored one of which was ‘It is important to be flexible and to work irregular hours if necessary’. The reliability index of this measure as expressed by its Cronbach’s alpha was .74.

Organizational identification. To measure organizational identification, five items reported by Mael and Ashforth (1995) were used. An illustrative item of this scale was ‘When someone criticizes this organization, it feels like a personal insult’. The Cronbach’s alpha indicating the measure’s reliability was .83.

Employee engagement. Employee engagement was measured with the 11-item employee engagement scale developed and reported by Saks (2006). The measure comprised two factors of employee engagement namely, job engagement and organization engagement. Example items from each of the factors were ‘I am highly engaged in this job’ and ‘Being a member of this organization is exhilarating for me’. One item from each of the factors was reverse-scored. An example of the reverse-scored items was ‘My mind often wanders and I think of other things when doing my job’. The reliability of this measure as depicted by its Cronbach’s alpha was .72.

EPEB. Employee perception of employer brand was measured by the 23-items employer scale developed and validated by Tanwar and Prasad (2017). Five dimensions of employer brand perceptions, denoted by the 23 items were healthy work atmosphere, training and development comprising six items each, ethics and corporate social responsibility and compensation and benefits with four items each, and work-life benefits with three items. Some example items of the overall measure were ‘This organization recognizes its employees when they do good work’ and ‘This organization provides its employees online training courses’. The Cronbach’s alpha denoting the measure’s reliability was .91.

Control variables. For all analyses that follow, respondents’ age, work experience, gender (1 = male, 2 = female), managerial position (1 = senior, 2 = middle, and 3 = junior), and the sector to which their organization belonged (1 = manufacturing, 2 = services) were treated as control variables. Age and work experience of the respondents were measured on a ratio scale and were calculated by rounding them off to the nearest year.

Analytical Techniques

In addition to the conventional bivariate techniques, the results and findings of this study were based on structural equation modeling procedures. As such, both, the measurement model as well as the path model were evaluated.

Initially, the uniqueness of the manifest variables measuring the latent study constructs was tested for common method bias using the single-factor method. This was followed by an inspection of the measurements’ reliability and validity. Additionally, the generalizability of the measures across groups was tested using the configural invariance approach.

The associations between the latent variables were first established using bivariate intercorrelations. This was followed by path analyses that utilized simultaneous regression methods to establish sequential associations between them. Specific tests were applied to establish the placement of the mediators as first- and second-order between EPOC and EPEB.

All the analyses mentioned above were conducted using the IBM SPSS 2624.0® and the IBM SPSS AMOS 24.0® statistical packages. The results and findings of the application of the above-mentioned analytical techniques are detailed in the next section.

Results

Common Method Bias

A single-latent factor approach was considered to test the presence of latent variable common method bias (CMB). For this study, a common latent variable associated with the manifest variables of the study constructs namely, EPOC, psychological contract, organizational identification, employee engagement, and EPEB was tested against the conceptual LVM proposed earlier (see Figure 1) to check for differences in model fit. The comparative-fit-index (CFI) and the incremental-fit-index (IFI) of the proposed model were .98 and .98, respectively whereas, the same indices were .77 and .77 for the common latent variable model. As such, the common latent variable model could not be accepted and this eliminated the risk of CMB in the proposed LVM.

Evaluation of the Measurement Model

The measurement model was tested by scrutinizing its reliability and validity as the main criteria of assessment (Ramayah et al., 2011). The composite reliability values ranged from .72 to .84 thus establishing construct reliability while the average variance extracted (AVE) values varied between .58 and .73 demonstrating convergent validity. Also, the squares of the intercorrelations between the study variables were less than the AVE values which provided evidence of discriminant validity. Additionally, the discriminant validity was attested using the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) method comprising values that spread from .36 to .58. These results are presented in Table 1 below.

| Table 1 Evaluation of the Measurement Model | ||||||

| Variables | CR | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1. EPOC | .84 | .73 | ||||

| 2. Psychological contract | .81 | .15 (.36) | .64 | |||

| 3. Organizational identification | .77 | .11 (.43) | .12 (.58) | .58 | ||

| 4. Employee engagement | .72 | .24 (.48) | .06 (.45) | .12 (.50) | .64 | |

| 5. EPEB | .83 | .07 (.39) | .12 (.49) | .12 (.53) | .14 (.47) | .70 |

Configural Invariance Tests

The results of the configural invariance tests confirmed that the measures were invariant between the various groups, that is, sector (Δχ2=377.2, Δdf=372, p=.42), gender (Δχ2=598.4, Δdf=668, p=.98), and LoM (Δχ2=995.3, Δdf=1027, p=.76) and therefore, the results obtained applied equally to all groups considered in the present study.

Descriptive Statistics, Intercorrelations, and Internal Reliabilities

Table 2 presents the mean, standard deviations, inter-correlations, and internal reliability indices of the key study variables. As anticipated, EPOC correlated positively and significantly with psychological contract and organizational identification (r = .39, p ≤ .01; r = .33, p ≤ .01, respectively). Further, psychological contract and organizational identification correlated significantly and positively with employee engagement (r = .24, p ≤ .01; r = .35, p ≤ .01, respectively). Finally, a positive and significant correlation was computed between employee engagement and EPEB (r = .38, p ≤ .01, respectively).

| Table 2 Descriptive Statistics, Inter-Correlations, and Alpha Reliability Indices | ||||||||||||

| Values (→) Variables (↓) | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1. Age | 37.24 | 8.62 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2. Work experience | 11.02 | 8.24 | .80** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. Sex | 1.37 | .41 | -.15* | -.13* | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4. Sector | 1.31 | .47 | -.04* | -.01 | -.14 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5. LoM | 2.39 | .64 | -.11 | -.16 | .07** | -.03 | 1.00 | |||||

| 6. EPOC | 3.53 | .69 | .04 | -.07 | .02 | .04* | -.02 | (.82) | ||||

| 7.Psychological contract | 4.09 | 47 | .03 | -.05 | .03 | .03 | -.03** | .39** | (.74) | |||

| 8.Organizational identification | 3.92 | .48 | .17* | .16* | .12 | .08* | .13 | .33** | .35** | (.83) | ||

| 9.Employee engagement | 3.65 | .42 | -.03 | -.02 | .05* | -.04 | .06** | .49** | .24** | .35** | (.72) | |

| 10. EPEB | 3.56 | .58 | .08 | .09 | -.06 | -.07* | -.05* | .26** | .35** | .34** | .38** | (.91) |

Path Analysis Results for the Proposed Model

The paths linking the study variables were tested through simultaneous regression procedures. As intuited, psychological contract (standardized β = .31, p ≤ .01) and organizational identification (standardized β = .23, p ≤ .01) regressed significantly and positively on EPOC thus supporting H1 and H2. Next, it was corroborated that employee engagement regressed significantly and positively on psychological contract (standardized β = .37, p ≤ .01) as well as on organizational identification (standardized β = .47, p ≤ .01) thereby confirming H3 and H4. Finally, EPEB regressed significantly and positively on employee engagement (standardized β = .43, p ≤ .01) leading to the acceptance of H5. The results of this analysis are displayed in Table 3 below.

| Table 3 Regression Analyses Result for the Conceptual LVM | |||||

| Values (→) Paths(↓) | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized β estimates | C.R.† | Remarks | |

| b | Standard error |

||||

| EPOC à Psychological contract | .59 | .03 | .31 | 11.47 | H1 accepted |

| EPOC à Organizational identification | .32 | .07 | .23 | 5.64 | H2 accepted |

| Psychological contract à Employee engagement | .42 | .04 | .37 | 4.82 | H3 accepted |

| Organizational identification à Employee engagement | .64 | .05 | .47 | 9.87 | H4 accepted |

| Employee engagement à EPEB | .56 | .06 | .43 | 8.22 | H5 accepted |

Mediation Analyses through Competing LVMs

To test the influence of mediation in the proposed conceptual model (see Figure 1), a sequential mediation approach was adopted. For this purpose, four LVMs were compared based on three absolute fit indices and four comparative fit indices. The absolute fit indices consisted of the normed χ2, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and the root-mean-square-error-of-approximation (RMSEA). The comparative fit indices included the comparative-fit-index (CFI), the incremental-fit-index (IFI), the normed-fit-index (NFI), and the relative-fit-index (RFI).

The four competing models tested in this section were labeled LVM1, LVM2, LVM3, and LVM4 respectively. In LVM1, EPOC and EPEB were featured as specific latent exogenous and endogenous variables exemplifying a model with no mediation. LVM2 incorporated the first-order mediators that are, psychological contract and organizational identification between EPOC and EPEB excluding mediation by employee engagement. The third model, that is, LVM3 comprised employee engagement as the single mediator between EPOC and EPEB. Finally, LVM4 represented the full model with EPOC as the latent exogenous, psychological contract and organizational identification as the first-order and employee engagement as the second-order mediators, and EPEB as the endogenous variable, respectively. When looking into the absolute and comparative fit indices of the four LVMs, only those related to LVM4, which represented the proposed conceptual LVM, were found to not only be above the recommended threshold levels but also had the best fit. For LVM4, the absolute fit indices that are, the normed χ2 was 1.23, GFI was .97, RMSEA was .04, and the comparative fit indices that are, CFI and IFI were both .96, NFI was .94, and RFI was .91. Therefore, LVM4 was chosen over the other three LVMs for further discussion. The results of these analyses are reported in Table 4 below.

| Table 4 Analysis of Competing LVMS | |||||||

| Values (→) Models(↓) | Fit Indices | ||||||

| Absolute Fit Indices | Comparative Fit Indices | ||||||

| Normed χ2 | GFI | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | NFI | RFI | |

| LVM1 (no mediation) | 3.12 | .92 | .07 | .92 | .92 | .87 | .85 |

| LVM2 (mediation with psychological contract and organizational identification only ) |

3.26 | .84 | .07 | .81 | .81 | .79 | .76 |

| LVM3 (mediation with employee engagement only) |

3.01 | .91 | .06 | .89 | .89 | .85 | .84 |

| LVM4 (mediation with all mediators) | 1.23 | .97 | .04 | .96 | .96 | .94 | .91 |

Additional Mediation Analyses for the Accepted LVM

Although the application of SEM procedures established psychological contract, organizational identification, and employee engagement as significant mediators and precluded problems of correlated measurement errors, it was decided to conduct the Sobel’s, the Aorian’s, and the Goodman’s tests as per the z-prime method (MacKinnon et al., 2002) to discount the possibilities of Type-I error while exploring the strength of mediation. Moreover, the ratios of the indirect effects on the total effects of all the mediated paths were computed and expressed as percentages and labeled as ‘percentage of mediation’. These results are presented in Table 5 below.

| Table 5 Additional Analysis of Mediation VIS-À-VIS LVM4 | |||||||

| Values (→) Paths (↓) | Additional Mediation Tests | Percentage of mediation | Path Analyses | Results of the additional mediation analyses | |||

| Sobel’s test | Aorian’s test | Goodman’s test | Whether regression estimate of (direct paths) > (paths under mediated condition)? | Whether regression estimate of (paths under mediated condition) is significant? | |||

| EPOC à Psychological contract à Employee engagement | 9.26** | 9.25** | 9.27** | 37.10 | YES | YES | All variables designated as mediators fulfill the quasi-mediator role |

| EPOC à Organizational identification à Employee engagement | 4.30** | 4.29** | 4.31** | 23.96 | |||

| Psychological contract à Employee engagement à EPEB | 6.97** | 6.95** | 6.99** | 28.85 | |||

| Organizational identification à Employee engagement à EPEB | 7.54** | 7.52** | 7.56** | 34.85 | |||

Two conditions for mediation were checked by an additional mediation analyses procedure. These were (i) whether the direct path from the primary antecedents to the final consequent variables was greater than the indirect path through the designated mediator variables and (ii) whether the direct path remained significant under conditions of mediation. Since answers to both were in the affirmative, all mediators in the proposed LVM were considered quasi-mediators.

A final test of mediation was performed on LVM4 using the specific indirect effects technique (Gaskin & Lim, 2018). According to the results of this analysis, all mediated paths vis-à-vis LVM4 were found significant. The results of this test are reported in Table 6 below. As a result, the H6 of the present study was also accepted.

| Table 6 Specific Indirect Effects for LVM4 | |||

| Indirect Path | Unstandardized Estimate | p-Value | Standardized Estimate |

| EPOC --> Psychological contract --> Employee engagement | 0.69 | 0.001 | 0. 52*** |

| EPOC --> Psychological contract --> Employee engagement --> EPEB | 0.98 | 0.001 | 0. 43*** |

| EPOC --> Organizational identification --> Employee engagement | 0.18 | 0.002 | 0. 14** |

| EPOC --> Organizational identification --> Employee engagement --> EPEB | 0.21 | 0.003 | 0. 17** |

| Psychological contract --> Employee engagement --> EPEB | 0.25 | 0.003 | 0. 18** |

| Organizational identification --> Employee engagement --> EPEB | 0.66 | 0.001 | 0. 21*** |

Discussion

The results adequately substantiated all the study hypotheses as well as the conceptual LVM operationalized as LVM4. In this section, the theoretical and practical implications of these results are discussed.

Theoretical Implications

The association of EPOC with employees’ psychological contract as per the first hypothesis indicates that the alliance between an organization and its employees is reciprocal when the former provides the latter with the contingent sense and meaning in response to their transactional efforts and relational adherence thereby implying the SET. The positive linkage between EPOC and organizational identification, reflected by the acceptance of the second hypothesis establishes the proliferation of an organization’s culture through various symbols and artifacts imprinting its schemata in its employees’ cognition, giving them an in-group character and thus confirming the notions propounded by the SIT.

The acceptance of the third and the fourth hypotheses endorsed that EPOC provides a strong employer-employee psychological concordance that results in more meaningful interactions. It also implies that once employees have internalized their organization’s image as their own identity, it becomes easier for them to make sense of their assigned responsibilities. As per the stakeholder theory, the common theoretical implication of the acceptance of both these hypotheses is that an organization should focus on creating value for its internal stakeholders who may consequently practice employer brand advocacy.

The acceptance of the fifth hypothesis implies that engaged employees not only indicate a conducive work environment but also the fact that they are psychologically secure and assured of what they can expect from their employing organization. Apropos the affective events theory, positive antecedents result in creating favourable perceptions about the organization’s employee value propositions for its employees. Finally, the acceptance of the sixth hypothesis is an attestation of the signal theory whereby organizations with deep-rooted cultures communicate a meaningful work environment giving them a singular identity motivating them towards higher levels of engagement and thus creating favourable perceptions of their employer’s brand. Thus, organizations with favourable EPOC and concurrently positive EPEB have fewer instances of employee cynicism, deviance, and/or voluntary turnover.

Practical Implications

Insofar as the first two study hypotheses linking EPOC to psychological contract and organizational identification are concerned, it should be understood that an organization’s policies and standard procedures are the outcomes of its underlying principles, ethos, and mores. Specifically, an organization’s HR practices such as its recruitment policy incorporating principles of person-organization fit, recognition of employees’ contribution through gifts of accessories and items that carry organizational logos and symbols, and skill and capability development as a key appraisal outcome for those employees who consistently achieve targets can all be practical ways through which organizations can ensure employees’ positive reciprocity in terms of a strong psychological contract and high levels of organizational identification that, as per their in-group organizational status, keep them both, job- and organizationally engaged and make them proudly display their employer’s brand. Additionally, organizations may also consider inviting employees to offer their ideas in strategic decision-making giving them a wider purpose that goes beyond their immediate tasks and career concerns and contextualizes their organizational engagement and affiliation.

Regarding the third hypothesis, its acceptance indicates that managers should emphasize activities that promote frequent socialization instances between employees across departments, divisions, and business units. This can be achieved through more team-based assignments and concurrent rewards and/or designing some organization-wide common evaluation criteria for such team performance so that there is a constructive competition which shall ultimately strengthen transactional as well as relational ties among employees resulting in organizational efficiency and effectiveness. At the same time, the outcomes of such activities shall be stronger levels of work and workplace-directed employee engagement. The implications of the acceptance of the fourth hypothesis can be encapsulated by recalling a statement by Sluss and Ashforth (2008; p. 811) that is, “organizational identification is more than just considering oneself a member of an organization; it is the extent to which one includes the organization in his or her self-concept”. To achieve this objective, managers should constantly co-create and co-design their employees’ work plans and goals in a way that highlights the latter’s organizational membership. Also, managers should help employees recognize how their success serves as a portion of departmental/divisional and ultimately overall organizational growth and success. On the other hand, employees’ inability to attain targets should be condoned and considered acceptable so long they are within the bounds of organizational legitimacy and as long as it is not habitual.

About the fifth hypothesis, its acceptance conveys the practical message that organizations should utilize their employees regularly and frequently for employer brand advancement. As such, they may be employed as employer brand ambassadors. This can be a viable and cost-effective alternative to explicit advertorials. Additionally, HR policies such as recruitment through employee referrals, garnering their feedback on the needs and feasibility of HR interventions ahead of implementing them, and incorporating employee suggestions while designing their performance management initiatives shall increase their engagement towards creating a perception of their organization as an attractive employer brand. The confirmation of the sixth hypothesis indicates the sequential interventions that managers should undertake to link EPOC and EPEB.

Limitations and Future Research Scope

The results of this study and subsequent theoretical and managerial implications discussed above should be interpreted within the confines of certain justifiable limitations.

First, this study was conducted among executives in managerial positions working in India and Indians by descent. As such, it does not cover the perspective of all employees of an organization irrespective of designations and also precludes cross-national comparisons.

While the accepted LVM4 was found most appropriate in fulfilling the objectives of the current study, the same may be studied cross-culturally, cross-nationally, and/or cross-temporally to capture the broader socio-cultural and diverse business contexts over time. By including the non-managerial workforce, employees who telecommute or work from home, and contract and part-time employees, future research can contribute to understanding employee attitudes and behavior apropos organizational policies and practices and their perceptions thereof in a more comprehensive manner. Finally, future research may replicate this study by incorporating more senior-level managers and executives since ultimately, they shall be the ones who shall be directly responsible for creating and maintaining culture and brand perceptions of the organization.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study ascertained certain gaps in the existing literature in the connections between EPOC and EPEB. Not only were studies concerning associations between these constructs scant in the related literature, but rarely were attempts made to include apposite intervening variables to explain their relationship. The research objective was, therefore, fulfillment of these research lacunae by linking EPOC with EPEB through intervening mechanisms concerning psychological contracts, organizational identification, and employee engagement. Accordingly, an LVM with the designated hypotheses was conceptualized and empirically examined. A specific LVM labeled LVM4 that represented quasi-mediation by all the designated mediator variables was accepted along with all the study hypotheses. The results and findings were then recorded. Several theoretical implications and managerial applications followed these study findings. Thus, the study contributed not only to addressing the research gaps but also in providing theoretical and managerial pointers. Notwithstanding its limitations, the study outlined certain cogent areas for future research.

References

Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185–206.

Bednar, J.S., Galvin, B.M., Ashforth, B.E., & Hafermalz, E. (2019). Putting identification in motion: A dynamic view of organizational identification. Organization Science, 31(1), 200–222.

Behery, M., Abdallah, S., Parakandi, M., & Kukunuru, S. (2016). Psychological contract and intention to leave with mediation effects of organizational commitment and employee satisfaction at times of recession. Review of International Business and Strategy, 26(2), 184–203.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Binu Raj, A. (2021). Impact of employee value proposition on employees’ intention to stay: Moderating role of psychological contract and social identity. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 10(2), 203–226.

Biscotti, A.M., Mafrolla, E., Giudice, M.D., & D'Amico, E. (2018). CEO turnover and the new leader propensity to open innovation: Agency-resource dependence view and social identity perspective. Management Decision, 56(6), 1348–1364.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Boukis, A., Gounaris, S., & Lings, I. (2017). Internal market orientation determinants of employee brand enactment. Journal of Services Marketing, 31(7), 690–703.

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2011). Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Demirtas, O., Hannah, S.T., Gok, K., Arslan, A., & Capar, N. (2017). The moderated influence of ethical leadership, via meaningful work, on followers’ engagement, organizational identification, and envy. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(1), 183–199.

Erkutlu, H., & Chafra, J. (2016). Impact of behavioral integrity on organizational identification: The moderating roles of power distance and organizational politics. Management Research Review, 39(6), 672–691.

Gaskin, J., & Lim, J. (2018). Indirect effects, AMOS plugin. Gaskination Statwiki, Retrieved from http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com/index.php?title=Main_Page (accessed 9 November 2022).

Giessner, S.R. (2011). Is the merger necessary? The interactive effect of perceived necessity and sense of continuity on post-merger identification. Human Relations, 64(8), 1079–1098.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Karjaluoto, H., & Paakkonen, L. (2019). An empirical assessment of employer branding as a form of sport event sponsorship. International Journal of Marketing & Sponsorship, 20(4), 666–682.

Kuroda, K., Ogura, Y., Ogawa, A., Tamei, T., Ikeda, K., & Kameda, T. (2022). Behavioral and neuro-cognitive bases for emergence of norms and socially shared realities via dynamic interaction. Communications Biology, 5(1), 1–13.

Lee, J., Chiang, F.F.T., van Esch, E., & Cai, Z. (2018). Why and when organizational culture fosters affective commitment among knowledge workers: The mediating role of perceived psychological contract fulfillment and moderating role of organizational tenure. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(6), 1178–1207.

Leicht-Deobald, U., Huettermann, H., Bruch, H., & Lawrence, B.S. (2021). Organizational demographic faultlines: Their impact on collective organizational identification, firm Performance, and firm innovation. Journal of Management Studies, 58(8), 2240–2274.

MacKinnon, D.P., Lockwood, C.M., Hoffman, J.M., West, S.G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104.

Mael, F.A., & Ashforth, B.E. (1995). Loyal from day one: Biodata, organizational identification, and turnover among newcomers. Personnel Psychology, 48(2), 309–333.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nazir, O., & Islam, J.U. (2017). Enhancing organizational commitment and employee performance through employee engagement: An empirical check. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 6(1), 98–114.

O’Reilly III, C.A., Chatman, J., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 487–516.

Pattnaik, S.C., & Sahoo, R. (2021). Employee engagement, creativity and task performance: role of perceived workplace autonomy. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 10(2), 227–241.

Raja, U., Johns, G., & Ntalianis, F. (2004). The impact of personality on psychological contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 350–367.

Ramayah, T., Lee, J.W.C., & In, J.B.C. (2011). Network collaboration and performance in the tourism sector. Service Business, 5(4), 411-428.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rodwell, J., Gulyas, A., & Johnson, D. (2022). The new and key roles for psychological contract status and engagement in predicting various performance behaviors of nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 1–14.

Saks, A.M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619.

Schein, E. H. (1983). Organizational Psychology (3rd ed.). New Delhi, India: Prentice Hall of India Private Limited.

Sluss, D.M., & Ashforth, B.E. (2008). How relational and organizational identification converge: Processes and conditions. Organization Science, 19(6), 807–823.

Soomro, B.A., & Shah, N.A. (2019). Determining the impact of entrepreneurial orientation and organizational culture on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and employee’s performance. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 8(3), 266–282.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Spoljaric, A., & Vercic, A.T. (2022). Internal communication satisfaction and employee engagement as determinants of the employer brand. Journal of Communication Management, 26(1), 130–148.

Swaroop, S., & Sharma, L. (2022). Employee engagement in the era of remote workforce: Role of human resource managers. Cardiometry, 23, 619–628.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2004). The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In J. T. Jost & J. Sidanius (Eds.), Political Psychology: Key Readings (pp. 276–293). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Tanwar, K., & Prasad, A. (2017). Employer brand scale development and validation: A second-order factor approach. Personnel Review, 46(2), 389–409.

Vough, H. (2017, April 26–29). Finding and losing meaning: The dynamic process of meaning construction in an architecture firm [Paper presentation]. The 22nd Annual Meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New York, NY, United States.

Received: 05-Jul-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16052; Editor assigned: 06-Jul-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-16052(PQ); Reviewed: 10- Aug-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-16052; Revised: 22-Aug-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-16052(R); Published: 01-Sep-2025