Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 3

Marketing And Society: Marketing Contribution Gaps Model

Pingali Venugopal, XLRI-Xavier School of Management

Abstract

The role of marketing in society has been an important focus area for researchers. While marketing could contribute positively to society, marketing communications promote materialism leading to misplaced consumption. Literature review has helped identify five marketing contribution gaps (in this paper, a negative impact of the marketing activities to the society is termed as a marketing contribution gap). Subsequently using a system approach a “Marketing Contribution Gaps model” with two embedded loops is conceptualized. Utilizing market information to develop relevant products to meet the consumer needs forms loop 1. Marketing information influencing consumption and consequent externalities forms loop 2. Three marketing contribution gaps identified in the literature are mapped on loop 1 and two gaps on loop 2. The systems approach highlights that a good feedback mechanism is essential for improving the quality of life. Suggestions are given for marketers and policy makers to improve marketing’s contribution to society.

Keywords

Quality of life, Developing Countries, Marketing Communication, Marketing Contribution, Consumer Aspirations.

Introduction

Over ninety “look alike and spell alike” variants of a popular fairness cream brand were found in rural markets of India (Kandelwal 2011). Look alikes are fake brands with similar packaging to a popular brand. Spell alikes are fake brands with changes in one or two alphabets from the original brand name (for example; Abidas, a spell alike for Adidas; Clavim Klain for Calvin Klein (India TV 2015)). From the company’s perspective it could be a problem of not being able to cater to the demand. However, from a macro perspective, it is unclear if the problem is with fake brands or unnecessary consumer wants. The question that needs to be answered is whether the rural people wants are misplaced?

Increased marketing communication has created the need for lifestyle products at the cost of basic and security needs in rural households. The poor reduce their consumption of essentials items to satisfy their higher order needs, for example the poor purchased imported chocolates, cosmetics over necessities (Banerjee and Duflo 2007, Subrahmanyan and Gomez-Arias 2008, Subramanian 2018). National Sample Survey (NSS) found that the rural communities are spending less on food as the purchase of non-food items in rural India increased from 27.15% in 1972-73 to 47.24% in 2011-12 (Mahapatra 2019). Shukla (2011) found the expenditure on cereals has gone down from 26% in 1987-88 to 16% in 2009-10; and Mar and Sethia (2018) found rural households prioritizing convenience products over health.

Wooliscroft & Wooliscroft (2018) questions whether the role of marketing systems is driven by profit for the organizations or to improve the quality of life of the consumer. Similarly, Varey (2013) questions the role of capitalism in enhancing the quality of life.

The socioeconomic foundations of marketing as building blocks of society are found in the writings of Plato, 24 centuries ago (Shaw 1995). The role of marketing in society has been an important focus area in macro marketing discipline.

Macro-marketing focuses on “(1) quality of life, (2) ethics (3) environment (4) systems, (5) history and (6) poor countries” (Peterson & Lunde 2016, p.105). Transformative consumer research (Brennan and Ozanne 2019) and transformative service research (Russell-Bennett et al. 2019) are also focusing on the impact of consumption on consumer wellbeing. While marketing communication could address poverty, poor health and environmental issues (Ingenbleek 2014, Kashif, et al. 2018), marketing did not contribute to social wellbeing (Pan, Zinkhan and Sheng 2007). Materialism and negative environmental consequences are a result of marketing activities (Varey 2010). Marketing systems have also increased inequality between the rich and the poor (Redmond 2018). While this problem is prevalent in developed countries also (Woolicraft and Woolicarft 2018), the impact is more severe for the developing economies.

Consumers in developing markets satisfy their needs with products designed for other consumer groups leading to reduced benefits (Witkowski 2005). Also, marketing communications promote social comparison leading to misplaced priorities in resource allocation; for example, desirability of “western” products in developing countries (Dholakia & Sherry 1987, Batra et al., 2000, Touzani, Fatma, Mouna, 2015).

As multinationals’ profit-motive has not been able to solve the needs of developing countries (Simanis and Duke 2014), the role of marketing in addressing social problems of the developing countries needs attention (Kashif, et al. 2018). Companies need to view marketing through the lens of social responsibility (Prosenak, Mulej & Snoj 2008). Taking a macro marketing approach, Layton (2009) connects development economics and marketing contribution to model marketing systems as a route to improving quality of life; and Redmond (2018) suggests a systems approach to address these market failures.

Though studies discussed about the negative consequences of marketing, an overarching framework to study the interrelationship of these consequences on the quality of life of the consumers is missing. Using the systems approach to study the interaction between the marketing systems and society, this paper proposes a “marketing contribution gaps model” to identify the role marketing is playing in contributing to the quality of life in developing countries. (The gaps model could also be applicable to the below the poverty line consumers in the developed countries with some modifications). The gaps identified can help develop effective marketing programs aimed at improving the quality of life. The gaps model could also be used to identify areas for policy interventions and compare the relative contribution of marketing to different social groups and different countries.

The next section presents the literature review to identify the contribution of marketing to the quality of life. The literature review section identifies the marketing contribution gaps. Next the conceptual model is developed, and the gaps identified in the literature are superimposed on the model. A case study of mobile phone usage in India is used to explain the gaps. Finally, managerial and policy implications are discussed.

Literature Review

Marketing is driven by the affluent group (Prosenak, Mulej & Snoj 2008) and the market forces underscore the needs of certain groups (McDonagh & Shultz II 2002). The literature review begins by highlighting the role of marketing systems in creating misplaced consumer aspirations and their impact on the society. In this paper, a negative impact of the marketing activities to the society is termed as a marketing contribution gap.

Misplaced Consumer Aspirations

Marketing promotes satisfaction through materialism (Varey, 2010) resulting in buying unwanted goods and services (Kashif, et al. 2018). As a consequence, consumption patterns in developing communities are similar to their counterparts in developed communities (Nagy, Bennett and Graham 2019). Therefore, even in less developed markets preference for products is dependent on the status associated with the product (Mitra & Pingali 2001) as social comparison and hedonism motivate consumption (Varey 2010).

Layton, (1986) found that marketing communications trigger the need to purchase expensive goods as it equated to higher status. The value a consumer derives from a purchase is relative to his/ her reference group (Pan, Zinkhan & Sheng 2007) and conspicuous consumption aims to indicate membership of a higher social class (Patsiaouras & Fitchett 2012) as purchases are a show of prosperity (Veblen, 1899). Romani et al., (2016) found that envy is commonly used in television advertising.

As marketing cannot create purchasing power (Ifezue, 2005), marketing communication influences consumers to shift their purchases to express themselves through association with products and brands (Varey, 2010). It has been seen that consumers in the bottom of the pyramid also use leading (global) brands (Nagy et al., 2019) as these brands provide status to the user (Eckhardt & Houston 2001). Witkowski, (2007) found American Fast Food chains were attracting even the less affluent consumers to their offerings.

Overall, purchase decisions influenced by social dimension (Peterson & Lunde 2016) lead to materialistic consumption and reduce social welfare (Shrum et al. 2014), as they promote excessive and unsustainable consumption in certain groups (Peterson & Lunde 2016).

Misplaced consumer aspirations would be a gap (Gap 1) in the marketing’s contribution to society.

Market Failure

Layton (2009) & Shawn (2011) term the market which is not working efficiently and not providing goods that are wanted by the consumers as market failure. Nason (1989) states that as economies grow the problem of market failures increase. Nason categories the social consequences of market transactions using a two-by-two framework; one dimension as foreseen and unforeseen consequences, and the other as direct or indirect effects. Market failure is a common phenomenon in developing countries and the degree and the kind of market failures in developing countries are different from the developed countries (Todorova 2016). Redmond (2018) links market failures to reduced consumer welfare.

Six types of market failures have been identified in literature (Redmond 2018). These are “imperfect competition, entry barriers, externalities, imperfect information, inequality, and transaction costs” (Redmond 2018, p. 415). This paper looks at imperfect competition (along with the barriers to entry and transaction costs); imperfect information and their impact on quality of life, inequality and externalities.

Competition and Entry Barriers

Opening the economies and inviting foreign direct investments have encouraged multinational companies (MNCs) to enter developing countries (Motohashi 2015). Witkowski (2007) supports it by stating that American Fast Food chains typically enter a developing country as soon as they open their markets. While on one hand MNCs can benefit the emerging economies, on the other hand they could suppress domestic competition (Pawar 2013) by building entry barriers (Redmond 2018).

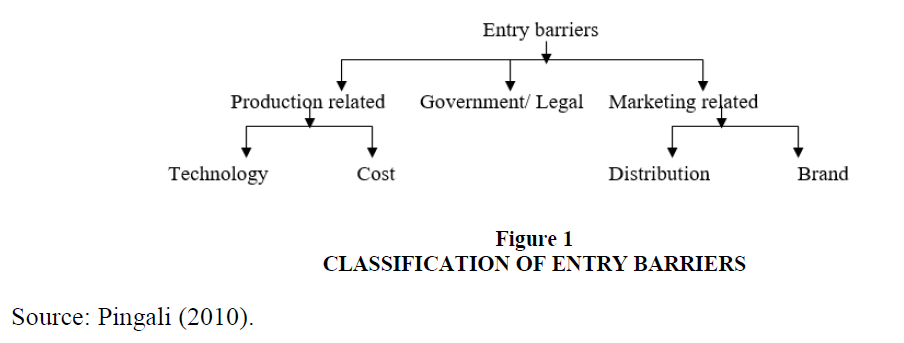

Figure 1 classifies the barriers to entry under three heads (government, production based, and marketing based). While government and legal can impact all the companies, individual companies can build production or marketing related entry barriers.

Marketing based Entry Barriers

Marketing based entry barriers focus on developing a strong distribution network and use of marketing communications to build brands. As seen in the earlier section, marketing campaigns have been promoting satisfaction through materialism (Varey 2010). Communication strategies which were successful in developed countries were found to be equally effective in developing countries (Witkowski 2007), as a result MNCs were able to promote consumption not suited for these countries (Rugraff and Hansen 2011). Consumers in developing countries who are not well informed about the impacts of consumption habits have become targets for adopting behaviours of the west (Redmond 2005). For example, the poor consume status products even though the products do not match their cultural requirements (Subrahmanyan and Gomez-Arias 2008). Witkowski (2007) also stated that marketing communications have resulted in Chinese children consuming western foods against their parent’s wishes. Kashif, Ayyaz & Basharat (2014) found similar results in Pakistan, while Popkin, Adair & Ng (2012) found similar results in other developing countries. So, MNCs by building strong marketing based entry barriers target the entire market and capture a large market share (Nagy, Bennett and Graham 2019).

Competitive offering would be a gap (Gap 2) in the marketing’s contribution to society.

Production Based Entry Barriers

The prerequisites for any marketing system to be effective are production, distribution capabilities and finances (Ifezue 2005). MNCs gain advantage over local firms through vertical integration, better technology and lower cost of production.

Vertical integration and collaborative actions increase production based entry barriers, reduce innovation, help gain greater market share (Redmond 2018), and reduce transaction costs for larger companies (Deng and Zhang 2020, Underhill 2016). For example, MNCs collaborate with each other to reduce costs (National Academy of Sciences 1998, Layton, 2015). Low transaction costs for MNCs, however does not indicate societal efficiency (Marinescu 21012) as technological superiority of MNCs may confine local players to low value add jobs (Rugraff & Hansen, 2011), also see case of mobile phone usage in the subsequent section).

Though technology transfer (to local players) could reduce transaction costs (Stavins 1994), technology from developed countries to local firms in developing countries may not be equally beneficial (Todorova 2016) as the need for continuous change of technology acts as a barrier for local firms (Varey 2010). While, procuring inputs at cheaper rate also provides a competitive advantage for global players (Witkowski 2007), high interest rates in the local money markets acts as an entry barrier for local firms (Mathur, Swami and Bhatnagar, 2016).

In summary, as Dai (2010) states MNCs not only maximize their profits but impact the economy of developing countries negatively by building barriers to entry for local firms.

Technology and Resources would be a gap (Gap 3) in the marketing’s contribution to society.

Information

Information is important for the success for any business (Wooliscroft and Wooliscroft 2018). “Affordability, quality, relevance and accessibility” of information (Redmond 2018, p 422) are essential for all firms operating in a system.

Markets with information asymmetries are inefficient (Kadirov, 2018). While, incomplete, or complete lack of, information impacts the local firms’ in developing markets to make appropriate decisions (implication drawn from Redmond 2018), multinationals’ decisions are backed by excellent marketing research (Wooliscroft and Wooliscroft 2018).

Again, providing quality information not only about the product use and precautions against misuse to the consumers but also about the negative impacts resulting from the consumption of the product to the non-consumers is essential for societal wellbeing (Lee and Sirgy 2004). While, marketing activities of MNCs revolve around creating an information pull (Varey 2013), consumers in less developed countries do not have access to appropriate information (Wooliscroft and Wooliscroft 2018). If consumers have less information about the quality of products, then there is a possibility of lower quality products replacing better quality products (Todorova 2016). Akerlof (1970) states that quality variations are a big problem in developing countries (quoted in Todorova 2016). Information asymmetry therefore leads to market failure (Redmond 2018).

Relevant Information would be a gap (Gap 4) in the marketing’s contribution to society.

Quality of Life- The Outcome

Marketing activities could influence quality of life (QOL) either in a positive or negative way (Pan, Zinkhan and Sheng 2007). To enhance quality of life marketers should not only focus on profit for the organization but also on the societal benefits (Lee and Sirgy 2004).

Increased economic activities focusing on materialistic life (Varey 2012) coupled with scarcity of resources (Inglenbleek 2014) is destroying the environment (Varey 2010) and reducing the quality of life (Varey 2013).

Externalities are side effects not incorporated in the cost calculations of the product. Since these are not included in the cost, companies tend to produce more (Mittelstaedt, Kilbourne and Mittelstaedt 2006); thereby, increasing the externalities both to the consumers and non-consumers. Dai (2010) points out that the transfer pricing mechanism used by multinational corporations could have adverse impact on the development of developing countries.

Market failures, such as information asymmetry (Redmond 2018); oligopolies (Wooliscroft and Wooliscroft 2018) and impact on environment (Stavins 1994) lead to negative externalities. Redmond (2018) also states that opportunistic behavior leads to negative externalities. Negative externalities would have a negative impact on quality of life.

Quality of Life, the outcome, would be a gap (Gap 5) in the marketing’s contribution to society.

Marketing Contribution Gaps Model

The role of marketing should be to improve the quality of life (Layton 2015) by developing and marketing products that make a difference to the lives of the people (Lee and Sirgy 2004). While marketing is blamed for focusing on short-term private, materialistic needs (Varey 2013), marketing should focus on building long-term relationships with all stakeholders by addressing social concerns (Lee and Sirgy 2004).

That is, companies using adequate knowledge from the market should identify relevant technologies and resources to develop appropriate products to satisfy the needs of the consumers. The consumers on the other hand should acquire appropriate information to discriminate and consume quality products to reduce the externalities.

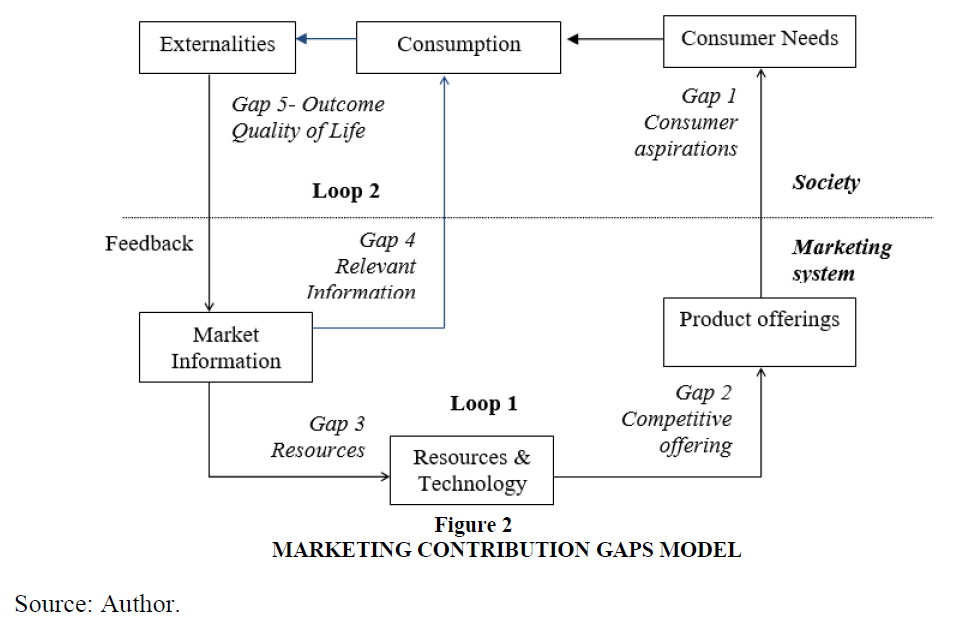

The conceptual model using a systems approach depicts the different stages of marketing as a stock and flow diagram to represent the logical stages in the real world. The stock represents the status of the dimension (for example available technology and resources). This is represented as a box in the model. The flow represented as an arrow indicates the impact a stock variable has on the subsequent stock variable (for example, the impact technology and resources has on the competitive product offerings). The flow could lead to a positive or negative impact to the society. As mentioned, a negative impact to the society would mean a marketing contribution gap. The gaps identified in the literature review section would be mapped on this model. The impact of a gap on the subsequent gaps could be additive (not discussed in this paper).

The marketing contribution gaps model built with two embedded loops capturing the interaction of society (consumers) and the marketing system is shown in Figure 2.

Loop 1 depicts the link of marketing system to consumers by connecting the availability of appropriate resources and technology for developing relevant products to satisfy the consumer needs. Resources gap (gap 3), competitive offering gap (gap 2) and consumer aspiration gap (gap 1) identified in literature review could be mapped to loop 1. Loop 2 depicting the link between consumption and the society, captures the acquisition of relevant information to consumption and its resultant externalities. The acquisition of relevant information (gap 4) and quality of life (gap 5) from the literature review could be mapped to loop 2. The information flow of the externalities back to marketing systems closes the loop (feedback flow).

The marketing contribution gap model is discussed using the case study of mobile phone usage in India.

A Brief Note on Mobile Phone usage in India

Mobile phones are seen as a multi utility product with symbolic attachment in India (Watkinsa, Kitner and Mehta 2012) as it enhances the status of the individual (FAO 2016, Talapatra 2020). Even the rural communities aspire to have a mobile phone (FAO 2016). Currently, the number of mobile phone users in rural India is higher than urban India (Mishra and Chanchani 2020).

Fashionable features determine status, so even low-quality cheap brands with fancy features are purchased (Talapatra 2020). A low-price strategy is increasing mobile phone based internet user base amongst the lower income consumers (Mitter 2020), including in media dark villages (Sharma, 2017).

Android brands dominate the Indian mobile market (Asher 2020) with around 50% of the mobile phones being imported. The remaining mobile phones which are assembled in India also depend on imports of the components, with value addition in India being only to the tune of 2-8% (Nawany 2016).

Again, only 3% of the mobile phone apps used by Indians are developed for India (42 Matters 2020). The mobile phone app usage, with 28.6% of app users being from the low income groups and 36.8% within the age of 25-34 (Statistica 2019), is expected to grow.

Though, mobile phone can be used to promote good health, reduce child mortality, maternal problems (eg: Bill Gates Foundation), dental care (eg: Colgate) (Sharma 2017) and government programs (Economic Times 2020 & Raja 2019); marketing communications and brand advertisements are influencing mobile phone usage mainly for entertainment and shopping (Talapatra 2020). Mobile phone advertising is also on the rise, accounting for around 30% of the media spend (Keelery 2020),

Proper guidelines for usage of mobile phones are not being given by companies (Arora 2019) leading to negative consequences on pregnant women and children (FCC n.d. and Nath 2018). Moisio (2003) states that these consequences are not due to the fault of the technology, but the way products are used. For example, over fifty percent of car crashes (Miller 2017) have been linked to mobile usage while driving.

Furthermore, the need to buy the latest models has contributed significantly to e-waste problem. Mobile phones which contribute to 12% of the e-waste in India are mainly recycled by the unorganized sector causing environmental problems (Bandela 2018).

Marketing Contribution Gaps in Mobile Phone Industry

The case is used to highlights the marketing contribution gaps in the mobile phone industry. Gaps identified are only indicative based primarily on the above noted statistic of mobile phone usage.

Loop 1: Marketing system gaps

Resource’s gap.

1. Mobile phone industry dependent on imported raw material and technology is not utilizing local competencies.

2. In India the research and development for designing products to protect the environment is insufficient.

3. Lack of adequate number of collection centers for e-waste.

There is a need to build local competencies to design products suitable for the local needs.

Competitive offering gap

1. Availability of low-quality mobile phone brands.

2. Value addition by fancy features.

3. Recreational apps available do not promote local culture.

Low quality mobile phone brands are a risk to the consumers. Apps from other countries are also promoting behavior contrary to the local values.

Consumer aspirations gap.

1. The consumers are incapable of discriminating the quality of the products/ brands.

2. Excess / misuse of mobile phones loaded with fancy features are harmful to the consumer’s health.

Desire for fancy features is forcing consumers to purchase and use low quality mobile phone brands.

Overall, the marketing systems are not contributing to the consumer wellbeing.

Loop 2: Societal (consumer) Gaps

Information gap.

1. Adequate information about the usage and externalities to the consumers and non-consumers is not available.

2. Information about proper disposal of discarded mobile phones is not available.

Lack of appropriate information about mobile phone usage is leading to negative consequences.

Quality of Life Gap.

1. Lack of knowledge of proper usage of mobile phones could lead to health problems to the users.

2. Environmental degradation due to mobile use/ disposal.

The externalities of mobile phone usage are contributing negatively to the quality of life. Overall, the societal loop is also contributing negatively to the quality of life.

Feedback

Though the externalities of mobile usage are highlighted by social agencies (Nath 2018), neither the companies nor the consumers are using the information to improve the quality of life.

In the case of mobile usage in India, both the loops are negatively contributing to the quality of life. If both the societal loop and the marketing systems loop contribute negatively, then the impact on the quality of life could be severe.

The negative impact of marketing contribution could be corrected if the consumers take a conscious stand in obtaining relevant market information (reduce gap 4- loop 2) and choose the right products to satisfy their needs (reduce gap 1- loop 1). That is, the consumers are not passively considering marketing communications but are actively seeking information about the externalities. A prerequisite to this is a strong feedback flow between externalities and market information. Also, refer to the policy implication section.

Marketing Implications

Developing countries are seen as an attractive market as they represent an enormous economic potential (Unite for Sight n.d), however companies even with excellent record in developed markets failed to offer products that took into account the social needs of the developing countries (Simaris, et al., 2008). Companies need to develop strategies by understanding the consumers’ requirements (Garrette & Karnani 2010).

Success would depend on developing innovative product and services (Ozegovic, 2011) aligned to the purchasing power (Adeola & Anibaba 2018) which not only provide value to the target group but also profit the company (Karnani, 2011). For example, Kickstart pumps to irrigate their crops (Jaiswal 2008) and credit card shared by different users (thebopstrategy.com 2012). A suggested plan for the 4Ps to address the social concerns is discussed (these could also be represented as the 4As used for the bottom of the pyramid customers)

Product (Acceptable)

Innovation which address local problems (Unite for Sight n.d) should “have relative advantage, compatibility, easily comprehended, trainability and observability” (Adeola and Anibaba 2018, p.151). Lehar Iron Chusti (Lehar Iron Health), the iron fortified snacks for adolescent girls suffering from iron deficiency, Godrej Appliances’ Chotukool, a portable refrigerator to take care of the food spoilage problem (Simanis and Duke 2014) are examples of such innovations. However, as there are no reference points for these innovative products, estimating demand could be difficult (Mathr, Swami and Bhatnagar 2016 and Simanis, Hart and Duke 2008).

Price (Affordable)

Selling lower priced products (Simanis 2012) and increasing availability would not be sufficient; the products should also provide value to the consumer (Simanis and Duke 2014). For example, SC Johnson focused on improving the health conditions of the poor in Nairobi (Simanis and Duke, 2014).

The product could also ensure affordability by bundling more value in a sale. For example D.Light and Duron—provide both light and recharging facility for mobile phones (Simanis 2012).

Place (Available)

Leveraging existing channel infrastructure would be a challenge as the breakeven can be achieved only after having a market penetration of over 30% (Simanis 2012). For example, Pur, Procter & Gamble’s water purifier powder, DuPont’s subsidiary Solae, soy protein intended to alleviate malnutrition, were withdrawn as they could not garner sufficient market share to be profitable (Simanis 2012).

Since the existing channel structure could be beneficial only if the consumers are aware of the product and its usage, there is therefore a need for nontraditional channels to reach consumers (Simanis & Duke 2014). For example, Partnership of Bajaj Allianz General Insurance with SKS, a microfinance institution to sell life insurance policies in India, Fan milk network of street vendors with a facility to sell dairy products in West Africa (Simanis & Duke 2014).

Promotion (Awareness)

Promoting new innovations/ products is challenging as people do not wish to change from their habitual practices (Simanis 2012). For example, consumers in sub-Saharan Africa who were not aware of the cause of malaria did not accept the insecticide-treated bed nets, despite the fact that it was effective and simple to use (Simanis & Duke 2014). Therefore, educating consumers about the problem and its solution is essential. For example, Dialog (Sri Lanka’s telecommunications service provider) trained women to teach villagers about the services (Simanis & Duke 2014); BRAC (Bangladesh) trains women entrepreneurs for its Essential Health Care program (Simanis & Duke 2014); Lafarge’s home-improvement counselors market the service through information kiosks (Simanis & Duke 2014).

As substandard products are a problem, educating consumers to identify low-quality brands not meeting the environmental standards (Simanis & Duke 2014) and counterfeit products (Jaiswal, 2008) is important.

Identifying Policy Interventions and Comparing Societies/ Countries

While many governments emphasize improving quality of life (Wooliscroft & Wooliscroft, 2018); marketing programs in most developing countries do not give importance to this objective (Ifezue, 2005). It is therefore critical to ensure that marketing systems are effective and efficient in satisfying the needs of the consumers.

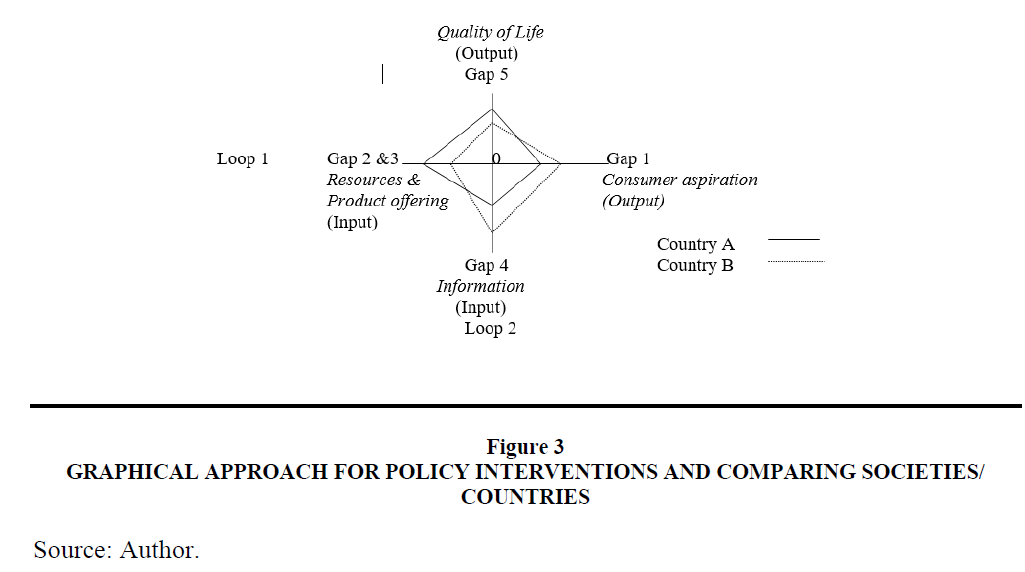

With the development of appropriate scales, the marketing contribution gaps model would help identify the resources gap, competitive offering gap, consumer aspiration gap, information gap and quality of life gap to formulate policy interventions.

The two loops can also be represented as a two-dimensional model Figure 3. This graphical representation could help understand the possible interaction of the two loops.

The graphical representation will also help compare different societies and countries to help them learn from the experiences of others. (This graphical representation is designed to capture only the negative contribution of marketing to society).

Each axis represents the input component(s) and the output component(s) of a loop as the two poles. The horizontal axis representing the market systems (loop 1) shows the cumulative score of the resources (gap 3) and the competitive offering (gap 2) as one pole (input) and the consumer aspirations (gap 1) as the other pole (output). The vertical axis representing the role of the consumers (loop 2) shows the information gap (gap 4) and quality of life (gap 1) as the input and output poles, respectively.

The scores on the input and output dimensions of the two loops can be plotted on the graph Figure 3. Farther a point from the center, greater is the gap on that dimension (input or output). Zero, the point of intersection indicates no gap (marketing is not contributing negatively to society on that dimension).

As a hypothetical case, values of two countries are mapped on the figure. In country A, though the cumulative effect of resources gap (gap 3) and competitive offering gap (gap 2) is high, the consumer aspirations gap (gap 1) is relatively low suggesting that even though the competitive offerings are not designed to meet the needs of the society, the consumer are not influenced by the competitive offerings. On the societal level, with a lower information gap (gap 4) the quality of life (gap 1) is relatively higher. This may suggest that the consumers are not utilizing the market information to reduce the impact on externalities. While the two axes may seem to be contradicting, it could imply that the consumers in country A understand the negative consequences to themselves but are not aware, or not considering, the negative consequences to the non-users and society. Based on these gaps policy interventions can be drawn for country A.

From Figure 3 it could be inferred that country B is opposite to country A. Country B with a lower cumulative resources gap (gap 2) and competitive offering gap (gap 3) may be promoting consumer aspirations (gap 1) to a greater extent. On the other hand, with a higher information gap (gap4) the country has a lower quality of life gap (gap 5). Though the two axes may seem contradicting again, it may mean that while the consumers in country B have relatively greater misplaced needs, the impact on the society is lesser than country A.

Using the mobile phone usage example, the consumers in country A may be using mobile phones considering their individual health, but they may not be conscious of the negative externalities of improper disposal. Consumers of country B, on the other hand may have a greater awareness about the consequences of mobile phone disposal on the society, though they may be overusing mobile phones (apps) ignoring their individual well-being.

The differences between the two countries could be due to the differences in feedback flow (refer figure 2) and/ or the role of the non-governmental organizations/ social groups in these countries. A good feedback mechanism is therefore, a prerequisite for improving the quality of life.

Conclusion

Marketing’s contribution to society has been an important area for research. Studies have identified six market failures negatively impacting the society, specifically the developing countries. This study using the systems approach conceptualized a Marketing Contribution Gaps model with two embedded loops. Utilizing market information to use available resources to develop relevant products to meet the consumer needs forms loop 1. Availability of relevant information to guide consumer usage and the consequent externalities forms loop 2.

Three gaps identified in the literature are mapped on loop 1 and two gaps on loop 2. The gaps model could help develop policy interventions to improve the flow and use of market information. The gaps model could be applicable to the below the poverty line consumers in the developed countries with some modifications, for example resources gap (gap 3) may need to be redefined.

The gaps model is not without limitations. The model has been conceptualized using the success/ failures studies referred by researchers. There may be several other cases not reported which can contribute to understanding the role of marketing to society. Another limitation is that the framework does not consider the role of social groups and other agencies working to protect the interests of consumers. In other words, additional loops could be added to account for the role of the social groups. Also as mentioned, the impact a gap has on the subsequent gap(s) and the cumulative effect of the two loops has not been discussed. These limitations could provide scope for future research.

Future studies could also identify more cases to strengthen the gaps model. The transformative consumer research and transformative service research could also be added to strengthen the gaps model. Research could also develop appropriate scales to measure the gaps.

Notwithstanding the limitation, the model could help improve the marketing contribution to society by developing appropriate marketing plans.

References

- 42 matters. (2020), “India App Market Statistics in 2020” (accessed September 12, 2020), https://42matters.com/india-app-market-statistics.

- Adeola, O. & Anibaba, Y. (2018), "Bottom of the Pyramid Marketing: Examples from Selected Nigerian Companies", Singh, R. (Ed.) Bottom of the Pyramid Marketing: Making, Shaping and Developing BoP Markets (Marketing in Emerging Markets), Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 151-163

- Akerlof, G.A. (1970), “The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3): 488-500

- Arora, M. (2019), “8 Harmful Effects of Mobile Phones on Children” (accessed September 12, 2020), https://parenting.firstcry.com/articles/harmful-effects-of-mobile-phone-on-child/. Asher, V. (2020). “Leading smartphone market share in India 2020 by model” Statistica.com (accessed September 12, 2020), https://www.statista.com/statistics/755685/india-smartphone-market-share-by-model/.

- Bandela, Dinesh, R. (2018). “E-Waste Day: 82% of India's e-waste is personal devices” (accessed August 2, 2020), https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/waste/e-waste-day-82-of-india-s-e-waste-is-personal-devices-61880.

- Banerjee, A. & Duflo, E. (2007). “The economic lives of the poor”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21 (1), 141-67

- Batra, R., Ramaswamy, V., Alden, D.L., Steenkamp, J.B.E., & Ramachander, S. (2000). Effects of brand local and nonlocal origin on consumer attitudes in developing countries. Journal of consumer psychology, 9(2), 83-95.

- Davis, B., & Ozanne, J.L. (2019). Measuring the impact of transformative consumer research: The relational engagement approach as a promising avenue. Journal of Business Research, 100, 311-318.

- Dai, X. (2010). “Study on Transferring Price Problem of Multinational Corporations”, International Business Research 3(3),122-125

- Deng, M. & Anlu, Z. (2020). “Effect of Transaction Rules on Enterprise Transaction Costs Based on Williamson Transaction Cost Theory in Nanhai, China”, Sustainability, 12, 1129

- Dholakia, N. & J.F. Sherry Jr. (1987). “Marketing and Development: A resynthesis of knowledge”, Research in Marketing, Delhi, Jai Press

- Domegan, C., McHugh, P., Flaherty, T., & Duane, S. (2019). “A Dynamic Stakeholders’ Framework in a Marketing Systems Setting”. Journal of Macromarketing, 39(2), 136–150.

- Eckhardt G.M. & Houston M.J. (2001), “To own your grandfather’s spirit: the nature of possession meaning in China”. In Asia Pacific Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 4, Tidwell P, Muller T (eds). Valdosta, GA, Association for Consumer Research, 251–257

- Economic Times (2020), “Indian to have 820 million smartphone users by 2022”, Economic Times, Jul 9, 2020 FAO. (2016), “Use of Mobile Phones by the Rural Poor: Gender Perspectives from Selected Asian Countries”, Rome,Food and Agriculture Organization.FCC. (n.d), “Effects of Using Mobile Phones Too Much” (accessed September 10, 2020), Federal Communications Commission https://ecfsapi.fcc.gov/file/7520941199.pdf,

- Garrette, B., & Karnani, A. (2010). Challenges in marketing socially useful goods to the poor. California Management Review , 52(4), 29-47

- Ifezue, Alex, N. (2005). The Role of Marketing in Economic Development of Developing Countries. Innovative Marketing, 1(1), 15-20.

- India, T.V. (2015). “10 brands and their duplicates” (accessed September 10, 2020), https://www.indiatvnews.com/buzz/who-cares/brand-and-their-duplicates-140.html.

- Ingenbleek, (2014).” From Subsistence Marketplaces Up, from General Macromarketing Theories Down: Bringing Marketing’s Contribution to Development into the Theoretical Midrange”. Journal of Macromarketing, 34(2), 199–212

- Jaiswal, A.K. (2008). “The Fortune at the Bottom or the Middle of the Pyramid?” Innovations. 3(1), 85-100

- Kadirov, D. (2018). “Towards a Theory of Marketing Systems as the Public Good”. Journal of Macromarketing, 38(3), 278–297

- Kandelwal, P. (2011), “Spot the Difference,” Financial Express, March 29

- Karnani, A. (2007). “The Mirage of Marketing at the Bottom of the Pyramid.” California Management Review. 49(4), 90-111

- Karnani, A. (2011). Fighting Poverty Together. Palgrave, Macmillian

- Kashif, M., Fernando, P.M.P., Altaf, U. & Walsh, J. (2018). "Re-imagining marketing as societing: A critical appraisal of marketing in a developing country context", Management Research Review, 41(3), 359-378

- Kashif, Muhammad; Mubashir Ayyaz & Sara Basharat. (2014). “TV food advertising aimed at children: qualitative study of Pakistani fathers’ views”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 26 (4), 647-658

- Keelery S. (2020). “Mobile advertising expenditure in India 2017-2023” (accessed Septmeber 12, 2020), https://www.statista.com/statistics/796777/india-spending-value-in-mobile-advertising-industry/#:~:text=Mobile%20advertising%20expenditure%20in%20India%20was%20recorded%20at%20over%2052,across%20the%20country%20by%202021.

- Mishra, D & Madhav, C . (2020). “For the first time, India has more rural net users than urabn”. Times of India, May 6, 6

- Mitra, Reshmi & Pingali, Venugopal. (2001). “Consumer Aspirations in Marginalised Communities: A case study of Indian Villages”. Consumption, Markets and Culture. 4(2), 125-144

- Mittelstaedt, J.D., Shultz, C.J., Kilbourne, W.E., & Peterson, M. (2014). Sustainability as Megatrend: Two Schools of Macromarketing Thought. Journal of Macromarketing, 34(3), 253–264

- Mitter, S. (2020). “With half a billion active users, Indian internet is more rural, local, mobile-first than ever” (accessed September 10, 2020), https://yourstory.com/2020/05/half-billion-active-users-indian-internet-rural-local-mobile-first.

- Moisio, R.J. (2003). "Negative Consequences of Mobile Phone Consumption: Everyday Irritations, Anxieties and Ambiguities in the Experiences of Finnish Mobile Phone Consumers", in Advances in Consumer Research Volume 30, eds. Punam Anand Keller and Dennis W. Rook, Valdosta, GA: Association for Consumer Research, 340-345

- Motohashi, K. (2015), Global Business Strategy Multinational Corporations Venturing into Emerging Markets, Japan, Springer Open.

- Nagy, M., Bennett, D. & Graham, C. (2019). "Why include the BOP in your international marketing strategy", International Marketing Review, 37 (1), 76-97

- Nason, R.W. (1989). “The Social Consequences of Marketing: Macromarketing and Public Policy”, Journal of Public Policy & Marketing , Vol. 8, Health and Safety Issues (1989), 242-251

- Nath, A. (2018). “Comprehensive Study on Negative Effects of Mobile Phone/ Smart Phone on Human Health”, International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer and Communication Engineering, 6(1), 575-581

- National Academy of Sciences. (1998). Global Economy, Global Technology, Global Corporations: Reports of a Joint Task Force of the National Research Council and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science on the Rights and Responsibilities of Multinational Corporations in an Age of Technological Interdependence 1998. Chapter 4, U.S. and Japanese MNCs and the Shape of Global Competition, Washington, National Academy Press.

- Ozegovic, E. (2011). Marketing to the BOP- A case study research, Copenhagen, Copenhagen Business School.

- Pan, Y., Zinkhan, G.M., & Sheng, S. (2007), The Subjective Well-Being of Nations: A Role for Marketing? Journal of Macromarketing, 27(4), 360–369

- Patsiaouras, G. & Fitchett, J.A. (2012), "The evolution of conspicuous consumption", Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 4 (1), 154-176

- Pawar, A. (2013), “Role of multinational companies in India”, International Journal of Scientific Research, 2(10), 1-4

- Peterson, M. & Lunde, M.B. (2016), "Turning to Sustainable Business Practices: A Macromarketing Perspective", Marketing in and for a Sustainable Society (Review of Marketing Research, Vol. 13), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 103-137

- Pingali, Venugopal. (2010), Marketing Management: A Decision-making approach, Delhi, Sage.

- Popkin, Barry M; Linda S Adair & Shu Wen Ng. (2012). Global Nutrition Transition and the Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries, Nutrition Review, 70(1), 3-21.

- Prosenak, D., Mulej, M. & Snoj, B. (2008), "A requisitely holistic approach to marketing in terms of social well‐being", Kybernetes, 37 (9/10), 1508-1529

- Raja Vidya. (2019), “Tring Tring! Nearly Three-Fourths of Rural India Has a Mobile Connection Now” (accessed September 10, 2020), https://www.thebetterindia.com/170458/india-mobile-connectivity-handset-rural-growth/.

- Redmond, W. (2018). “Marketing Systems and Market Failure: A Macromarketing Appraisal”, Journal of Macromarketing, 38(4), 415–424

- Romani, S., Grappi, S. & Bagozzi, R.P. (2016), "The Bittersweet Experience of Being Envied in a Consumption Context", European Journal of Marketing, 50 (7/8), 1239-1262

- Rugraff Eric & Michael Hansen. (2011). Multinational Corporations and Local Firms in Emerging Economies, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press.

- Russell, R., Fisk, R.P., Rosenbaum, M.S. & Zainuddin, N. (2019), "Commentary: transformative service research and social marketing – converging pathways to social change", Journal of Services Marketing, 33 (6), 633-642.

- Sharma, M. (2017), “Mobile handset penetration: Why rural consumer is not rural anymore”, Financial Express August 1, 2017, 5

- Shaw, E.H. (1995). “The First Dialogue of Macromarketing”, Journal of Macromarketing, 15(1), 7-20.

- Shawn Cunningham. (2011). Understanding Market failures in an economic development context, Pretoria, SA, Mesopartner Monograph 4.

- Shrum, L.J., Tina M. Lowrey, Mario Pandelaere, Ayalla A. Ruvio, Elodie Gentina, Pia Furchheim, Maud Herbert, Liselot Hudders, Inge Lens, Naomi Mandel, Agnes Nairn, Adriana Samper, Isabella Soscia & Laurel Steinfield. (2014). “Materialism: the good, the bad, and the ugly”, Journal of Marketing Management, 30(17-18), 1858-1881

- Shukla, R. (2011). “Changing consumption basket,” The Economic Times, September 26, 7 Simanis, E. (2012), “Reality Check at the Bottom of the Pyramid”, Harvard Business Review,June 2012

- Simanis, E. & Duncan D. (2014). “Profits at the Bottom of the Pyramid”, Harvard Business Review, October 2014

- Simanis, E., Hart, S. & Duke, D. (2008), “The Base of the Pyramid Protocol: Beyond ‘Basic Needs’ Business Strategies.” Innovations. 3(1), 57-84 Statistica. (2019). “Apps, India” (accessed September 12, 2020), https://www.statista.com/outlook/318/119/apps/india#market-age.

- Stavins, R.N. (1994). “Transaction costs and Tradeable permits”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 29, 133-148

- Subrahmanyan, S., & Gomez-Arias, J.T. (2008). Integrated approach to understanding consumer behavior at bottom of pyramid. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(7), 402-412.

- Subramanian, P. (2018). “Three Billion Rural Consumers-Can marketers profit from them?” (accessed August 24, 2020), https://medium.com/texas-mccombs/three-billion-rural-consumers-can-marketers-profit-from-them-792d141049f4.

- Talapatra, A. (2020). “How Rural Millennials Are Choosing Their Smartphone”, Buisnessworld, September 11, 2020 Thebopstrategy.com. (2012), “4As and 5ds of marketing for BoP population”, February 29, 2012 (accessed September 4, 2020), http://www.thebopstrategy.com/.

- Todorova, T. (2016). “Transaction Costs, Market Failure and Economic Development”, Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics, 7(3), 672-684

- Touzani, M., Fatma, S. & Mouna Meriem, L. (2015), "Country-of-origin and emerging countries: revisiting a complex relationship", Qualitative Market Research, 18(1), 48-68.

- Underhill G.R. (2016). “Markets, Institutions, and Transaction Costs: the Endogeneity of Governance”, Conference: Society for Institutional and Organizational Economics, Montréal. niteforsight (n.d.), “Social Marketing at the Base of the Pyramid” (accessed September 4, 2020), http://www.uniteforsight.org/social-marketing/base-of-pyramid.

- Varey, R.J. (2010). Marketing Means and Ends for a Sustainable Society: A Welfare Agenda for Transformative Change. Journal of Macromarketing, 30(2), 112–126.

- Varey, R.J. (2013). “Marketing in the Flourishing Society Megatrend”. Journal of Macromarketing, 33(4), 354–368.

- Varey, R.J. (2012). “The Marketing Future beyond the Limits of Growth,” Journal of Macromarketing, 32(4), 421–430

- Veblen, T. (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class, New York, Penguin.

- Watkinsa J., Kathi R. Kitner & Mehta D. (2012), “Mobile and smartphone use in urban and rural India”, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 26(5), 685–697

- Witkowski, T.H. (2007). Food Marketing and Obesity in Developing Countries: Analysis, Ethics, and Public Policy. Journal of Macromarketing, 27(2), 126–137

- Witkowski, T.H. (2005). Antiglobal challenges to marketing in developing countries: exploring the ideological divide. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 24(1), 7-23.

- Wooliscroft, B., & Ganglmair-Wooliscroft, A. (2018). “Growth, Excess and Opportunities: Marketing Systems’ Contributions to Society”. Journal of Macromarketing, 38(4), 355–363.